This was originally published at The Rumpus on April 24, 2017.

By mid-morning, it was so hot her breath felt as if it were being drawn back into her. She took the tin washbasin out to the front yard, filled it with cold water, and shampooed her hair. If she turned her head, she could watch her reflection in the kitchen window as she leaned over the tub. Her hips seemed so wide in that position, tapering down from the wraparound skirt to legs that were girl-like. She watched her hair turn from yellow to brown with the wetness.

Around noon, with her hair now sticking to the back of her neck with perspiration, she heard the screen door slam once, then again. It was odd for him to come home in the middle of the day.

She went to the kitchen but he was already gone. This was the way he did things. She looked at the kitchen table for a box, some sign of the gift she was sure he would sneak in and leave her just as he had every anniversary. She heard his truck backing down the dirt drive. There was no chance she’d catch up with him.

This time of day, the sun came in through the slatted windows and settled on the yellow linoleum in stripes. Now she saw it. There lay her gift, basking in the sunlight. A gray-green lizard the size of a shoe. It stood so still she thought it was fake. A joke he had played on her, like the time he told her he was fixing the kitchen faucet and put a gag faucet where the real one had been. She remembered how she ducked and screamed, thinking she would be splashed with water when the new faucet came off in her hands.

But this was not plastic. He had tied a long piece of thick string from one of the lizard’s ankles to the kitchen table. Around the neck was a thin yellow crinkly ribbon that she had seen him pull out of the junk drawer the day before. She had suspected it was to wrap her gift. The ribbon was tied sideways around the animal’s neck in a bow. The lizard squinted as it turned its head slowly to look around the room. Its bulgy, liquid eyes scared her. She moved and the thin plates of skin on its back stood up. Now it turned its head swiftly and the scales rippled as if it were shivering.

She heard herself sigh, rubbed her hands on her skirt, and walked toward the white pine cupboards, making a full circle around the lizard’s body. It watched her. She found an aluminum pie pan under the sink and grabbed the pitcher of cold water from the refrigerator. She put the pan on the floor, poured the water in, and inched it over to the animal with a broom, backing away quickly and waiting to see if it would drink. The lizard sat on its squat legs and narrowed its lids into slits like cat’s-eye marbles. It appeared to be asleep.

Throughout the day, she kept going to the kitchen to check on it, afraid it might get loose in the house. In the late afternoon, she stood a distance away and threw a leaf of Bibb lettuce by the pie pan. She didn’t want anything to do with it, but she didn’t want it to starve. The creature, startled, was set into motion, skittering back and forth, first in one direction, then another, yanking itself back again and again by the string. For a while, she took a seat across from it, leaning forward. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, she said.

She finished cleaning the house and had no choice now but to come back to the kitchen. She had to clear out everything to wash the floor, which meant moving the tables and chairs and putting it somewhere. Outside was where she wanted it. She could tell him it escaped, ran away. But that wouldn’t be honest and if they had promised each other anything when they married, it was honesty. Letting his gift run away, or rather, pushing his gift out the door, wouldn’t be a white lie. It would be flat-out deception.

She moved the chairs into the hallway and tried to untie the string, cursing him for making a knot she couldn’t undo. She went to the junk drawer, took out the scissors and, grasping the string, clipped it quickly and led the lizard toward the kitchen door, then the porch, like a dog on a leash. When she opened the screen door, the lizard tried to run back inside, as if it were afraid of the outdoors. She pulled it along, but it planted all four paws firmly on the floor. Its nails made a pitiful sound on the linoleum, then became stuck on the doorjamb. She gave a tug and over it rolled, like a child’s toy truck. Another tug, and it was up again and furious and ran towards her. It followed her the whole length of the porch until she scooted over the banister and tied it to one of the posts. She walked around to the back of the house and let herself in.

What a gift, she thought. Her present for him was wrapped and put away in a bedroom drawer days before he suggested they skip gifts this year. She had bought him a new jacket and white shirt. She undid the ribbon to look at them, then replaced the clothes and surrounded them with tissue paper. They looked so nice she took the shirt out again and held it up to her cheek. It felt so crisp and cool.

When the day had cooled, she bathed and changed into a fresh cotton dress and lifted her hair away from her neck to pin it up.

*

“What’s it doing out there?” he said when he came home. “Don’t you like it?”

On the table, she had put a candle and the gift box in navy blue paper and the good dishes, but he didn’t look at those.

“What’s it doing?” she said absently, for she had taken him to mean that the thing was doing something interesting or different and that she should go and look.

The lizard stood very still, as if it might be dead. The bow was gone.

“Why’d you put it out there?” he said.

“Because it belongs out there,” she said as she closed the screen door.

From the heat, his black hair had separated into individual strands, making him look older and scraggly.

“You didn’t like it,” he said and began to follow her around the kitchen.

She retrieved his favorite pasta dish from the oven and the salad from the refrigerator and he followed right behind. Their bodies made a shadow on the yellow floor that looked like the silhouette of two shy, hesitant boxers in a ring.

“Oh, I like it,” she said. She was intent on getting the dinner ready and didn’t look at him. “I like it just fine. You didn’t pay any money for it, did you?”

His face looked tight.

She motioned toward the window with her cooking mitt. “It’s just that there’s a million of them out there, and it’s a shame to throw away good money after one.”

“I bought it, all right? Cheap. From a guy at work. I thought you’d like it. I thought you’d think it was funny.”

“I do think it’s funny. I laughed.”

“It’s really neat,” he said, trying to convince her. “It looks prehistoric or something.”

She made him sit through dinner before opening his package.

She expected him to say, I thought we agreed, but he didn’t. Instead, he looked eager, put his glass down, and said, “Well, let’s see what this is.”

He seemed stunned for a moment when he saw the clothes and then whistled low as he lifted them out of the box. He felt the material, ran his fingers down the length of the lapel, and smiled at her. “This is a good one. But what‘s it for? God knows there’s nowhere around here to wear this.” And then he laughed and said, eyes crinkling, “What have you got up your sleeve? I think you must be up to something, baby doll.”

“They’re interview clothes. You’ll need something nice to interview in if you try to get transferred back home or if you go to another company. Isn’t that why we came here? So you’d have a better job after this one? The next step up, you said.”

He went back to examining the jacket, rose half out of his chair and sat down again.

“Isn’t it?” she repeated and motioned with the back of her hand to the open bedroom door. “Try it on.”

He was standing now. He had the jacket on and went to the mirror, looking at himself this way and that, sizing up every angle.

“I told you,” he said. “I’ve got to put in a couple of years first before I’d even try to move on. You don’t just go looking for another job when you’ve hardly been here. You have to pay your dues.” He ran his hand through his hair. “I was hoping that once you were here for a while, you’d like it.”

“What’s there to like?” she said. She began biting some ragged skin on her bottom lip. She fingered the rim of her glass. She knew her voice sounded bitter but she didn’t care. “You told me about the place. Patience, you said. You’d have to be brain-dead to have this much patience. To want to live here. You’d have to be a fool.”

He stepped in front of her. “I’m a fool then,” he said, sticking his hands in his pockets.

“You’re a fast learner. Everyone has always told you that. You’ll find another job. You don’t have to stay at that place.”

“You don’t want me to blow what I have, do you? If they get wind of me applying other places it won’t look good. And if I go in there now and ask the boss for a transfer back to where I came from, they’d die laughing. There are other guys, ahead of me, willing to pay their dues.”

She thought of those other men and what they and their wives must be like to be so patient, so accepting. She found herself wondering, for the first time since they had been together, what other kinds of men she could have married. Maybe I should have waited, she thought. And then she thought, I’ve heard about this. This is how things change.

“You act as if I don’t know what I’m talking about,” he said. “They said I’d have to wait two years for a transfer. At least two years.”

“Oh, great,” she said, fingering the glass again. “I’ll be dead in two years in a place like this.”

He smiled at her. “There she is. My melodramatic sweetheart.”

He removed his jacket and draped it neatly over his chair. He stepped behind her and put his arms around her.

“Look,” he said. “Baby doll. This is nothing. We’ll laugh about this later. It’ll be a story. Like a joke about how many miles we walked to school when we were kids.”

She looked through the window to where there was a thin stream of orange light across the horizon and nothing more. Some people might think the sight was beautiful. To her it had become barren.

“Let’s eat,” she said. “It’s getting cold.”

And in the end, after they had finished dinner and lain together and after she waited for the movements of his body to cause hers to shiver, she turned on her side and closed her eyes. He put his hand on her hip and said in a whisper, “Baby doll? You still awake?”

She was in the lazy space between wakefulness and sleep and, so, didn’t answer. She thought she heard the animal stumbling off the porch, down the steps, and into the night, finally free.

Before she dreamed, an image came to her of the liquid eyes. As she began to fall asleep, her body jerked, quick and hard. She felt as if she were jumping straight up into darkness.

***

Rumpus original art by Aubrey Nolan.

Photograph by Nicolaia Rips.

When he walked into my bedroom for the first time, he pointed at the top right corner of the room. “What is that?”

The answer was a hole. Directly above my closet and several inches below the start of my ceiling is an obvious nook—a deep-set crawl space suspended inside my wall. If that weren’t fun enough—“fun” said through gritted teeth, like how the realtor said “Now, this is fun” when he showed me the nook—there’s another feature: a bolted door within the nook. A dusty, intrusive, and creaky wooden door that points up to the sky. Between the bolts that secure the door is a sliver of light, slim enough that you can’t see what’s on the other side.

My building is an old Boerum Hill brownstone with a criminal exterior renovation. Inside my bedroom, though, the floors slant and the ceiling droops. It’s a beautiful princess bedroom, if the princess never got saved and lived forever unmedicated in her virginal bedroom. It’s a room of illusions, and the nook is its most illusive element. The nook is the last thing I see every night before I go to sleep. Goodnight Moon, good night dollhouse room, good night nook.

He was the first person I dated after a catastrophic college relationship. He was sweet. He reminded me of a portrait of a medieval saint or a beautiful lesbian. He asked questions.

“What are your dreams for the future?” Don’t know. “What did you want to be when you were small?” Taller. “Where does the door in the nook go?” Not sure. “Have you ever opened it?” Never. “Never?” Never ever. From my bed he would stare at it, and the more I tried to ignore it, the more he pushed. “What if there’s something amazing up there?” And what if there isn’t. Here we are in my bed, I thought, no point in fantasy.

He believed doors were made to be opened. I believed, firmly, that some doors should not be. Locked basement doors, closed bedroom doors, the door to a safe, the attic door in a horror flick, a patio door on a burning summer day when the AC is on, the seventh door in Bluebeard’s Castle. He argued for letting in the elements; I, for the threat of a draft. I could unleash a spirit or an alien or a doll left up there imbued with the spirit of a child born during the Depression or of some creep who studied acting at an Ivy League. A ghost is like a pet or a child, and I’m not responsible enough to handle a poltergeist.

Unfortunately, my refusal to deal with the door rendered the whole nook a lost space. There, above my head, was a nook the size of a rich child’s tree house, and I was neglecting it. It was large enough that I imagined I could stand in it fairly comfortably. Being raised in Manhattan, I started to obsess about the nook. I could rent it out as a fourth bedroom. I could use it as off-season storage for several lumpy hand-knit sweaters I felt too guilty to get rid of. I could build a library in it for books I’d stolen and borrowed. In fact, he was upset that I’d never read any of the books he’d lent me. He noticed I was using his favorite book as a coffee coaster.

Our relationship, like most organically sweet things, rotted. When he dumped me, he said there was a disconnect. He said maybe we’d find our way back to each other, and I said we would not. A classic door-half-open divide: he tried to keep it open, but I bolted it shut.

A few days after we broke up, I propped a chair against the wall and scrambled upward. Halfway into the nook, my arm strength dissolved. I dangled, my tush protruding from the wall, wiggling stupidly. I considered shouting for my roommate. Then, I considered her laughing at me. Maybe, I thought, I should just allow myself to be stuck. It’s fine to be stuck. I continued up. There I crouched, panting, in the crawl space, jamming at that ungiving door. With a crack it broke.

From the waist up I stuck out through the ceiling. I could see over Brooklyn. Brooklyn could see over me—a ghoulish, dust-covered, and bizarrely grinning woman escaping from an attic. I wedged myself up further. Suddenly, I was on the tilted roof. The door was open and there was nothing to be scared of. When one door closes, God opens a trapdoor.

Nicolaia Rips is the author of the memoir Trying to Float: Coming of Age in the Chelsea Hotel.

During her MFA, Francophone writer Emilie Moorhouse serendipitously discovered the works of a little-known Surrealist poet, Syrian-Egyptian-English Joyce Mansour, who chose to write exclusively in French. Mansour, a glamourous, married woman who came of age as an artist in 1950s Paris under the wing of André Breton, existed as a kind of glitch in the French literary scene—an upper-class, Arab, apolitical woman who refused to become a sex object while making unapologetically sexual work. Emerald Wounds (City Lights Books) is the result of Moorhouse’s deep dive into the fringes of Francophone literature, translating Mansour’s wide-ranging poetry and asserting her right to be known. In this career-spanning edition, Mansour exists as a writer’s writer, a reluctant feminist, an Arab Jew, and most blatantly as a kind of queer “uber-wife,” pissing in her husband’s drink while flying on the freeway between sex and death.

I recently spoke to Moorhouse on Zoom about the life and work of Joyce Mansour as her Wi-Fi was being changed—the warbling sound of a hole being drilled somewhere above.

***

The Rumpus: How, technically, did you find Joyce Mansour?

Emilie Moorhouse: I was taking a translation course—this was in 2017, and the #metoo movement had just exploded and I thought, “I need to translate a woman who is controversial, someone who the literary establishment doesn’t approve of” which, okay, many women have not had the approval of the literary establishment. But I think I was looking for raw emotion, for a woman who could express her sexuality and who could speak her truth whether it fit in with the times or not. So that was kind of the criteria that I set for myself. And I did find quite a few women like this in Francophone literature, but in the Surrealist tradition or practice, a lot of it is stream-of-consciousness writing. And so, what Mansour was writing was naturally uncensored.

Rumpus: Reading Mansour’s origin story as a writer, I found it obviously compelling but also kind of curious, because there’s this story of her being in a state of grief, both from her mother dying when she was fifteen and from her first husband dying when she was eighteen, and the story is that her grief forced her to write. It was either the madhouse or poetry. That’s obviously a very compelling story behind a first book, right? Especially with the title of Screams from a beautiful, foreign, young woman in 1953 arriving on the Parisian literary and art scene. I wonder if there’s anything problematic in this origin story in your opinion. Is it constructed? Or do you think, in an alternate timeline, Mansour could’ve just been a happy housewife with her rich, much older, French-speaking second husband?

Moorhouse: Well, I think she would have been involved in the arts. There is this really strong personality in Mansour. And as much as she was shaped by the events of her youth, she does have such a rich background as well. She was bilingual before she met her second husband, speaking fluent English and Arabic. So, she obviously had this very rich and interesting life, you know, in tandem with these early events. But at the same time, and I’ve never heard it mentioned in any of the interviews, or, in any research that I did, that she was writing poetry, prior to these events. I guess life is life.

Rumpus: So, in sticking a little bit with her biography before getting to the work, when reading about Mansour’s second husband—which sounded like a problematic relationship in that he had lots of affairs—I feel like in a way that Mansour had this despairing, mourning and grieving personality versus a kind of desiring personality, especially desiring of men who she couldn’t really possess. Do you feel that her second husband supported her, especially the notion of the confessional in her work? I wonder if he even read her work?

Moorhouse: Yeah, I also wondered about that. I know that her son read her work and he actually helped correct her grammar, her French mistakes. And I do know that she never discussed her first husband with her second husband but that her second husband sort of swept her off her feet. He kind of gave her life again after the death of her first husband. But her second husband was not someone who was initially very involved in the arts. Apparently, André Breton hated him! Breton did not consent to Mansour’s husband, basically. He came from a very different world than Breton.

Rumpus: I have a lot of questions about the relationship between Mansour and Breton. In Mansour’s poetry, there’s a lot of female rage against the husband or the lover, even as she is taking pleasure in them. It reminds me of the line in one of her poems: “Don’t tell your dreams to the one who doesn’t love you.” I wonder if there’s this irreconcilable split in Mansour’s life between her domestic life and her artistic life. I was thinking a lot about Breton and his mentorship of her in this way. I think it’s interesting in your intro that you state that they were definitely not lovers.

Moorhouse: I was never able to explicitly find any information that Mansour and Breton were sexually involved, and one of her biographies explicitly states they were never lovers. I think Mansour’s artistic side was really nourished through Breton. They went to the flea markets of Paris every afternoon together in search of artwork. And I do think that Mansour’s second husband, through Mansour, started to develop a greater appreciation of artwork. But it wasn’t something that he was involved in initially and so I really don’t know how present he was in her artistic practice.

Rumpus: You label Mansour’s poetry as erotic macabre. Can you break that term open a bit? I am thinking of her work’s relationship to 60s and 70s French feminism (like écriture feminine) but I’m also thinking of the somewhat contrasting pornographic strain in her work, akin to Georges Bataille.

Moorhouse: I do see it as both. I think she gets inspiration from both. Bataille was very erotic macabre, or maybe he’s a little bit more twisted than that even, but this whole idea of la petite morte (death is orgasm), I do see influences from that in her work. But I don’t think Mansour was loyal to any kind of movement. I mean, she was obviously very loyal to the Surrealists, but when she was asked to write for a feminist magazine, she bristled and said, “Feminism, what do you mean?” I think Mansour liked to remain independent and have her creativity be independent from these different movements. She was apolitical. And I think some of that comes from Mansour’s experience in Egypt, being exiled because she was part of this upper-class Egyptian society, her father was imprisoned and most of his property and assets were seized by the government and apparently, he refused to ever own a house again and lived the rest of his life in a hotel. Then you have the Surrealist movement, which Joyce Mansour was a part of, which was more aligned with anarchism. She was kind of caught between two worlds.

Rumpus: It’s interesting, this idea of Mansour being apolitical and having a sort of disconnect from feminism, because it seems to bring up things around the Surrealists having issues with women, with women being objectified or fetishized in their work, this idea of “mad love” trumping all, even abuse. And so, if we just, say, insert Mansour into our present-day politics—and this is a totally speculative question—how do you feel she would fit into our polarizing and gender-fluid times?

Moorhouse: Well, my impression of her work is that it is very gender-fluid, she plays around with gender in her writing quite a bit, so I feel like she absolutely would, in a way, fit into our now. In terms of the political, that’s a good question because, yeah, everything is very polarized and politicized today. Also, I don’t know that she wasn’t necessarily political. I think she obviously sympathized with many progressive movements and that’s clear in her writing. That includes feminism. She was openly mocking articles that appeared in women’s magazines imposing unrealistic housewife-style standards. She mocked beauty standards and even the condescending tone they had when advising women on how to behave “nicely.” So she obviously did have certain strong leanings. But I think outside of her art, Mansour wasn’t necessarily willing to pronounce them. It was more like my art speaks for itself.

Rumpus: I think that’s probably still the best way of being an artist. And also, it’s not really a speculative question, because we will soon see how Mansour’s work is received with a younger, contemporary, potentially genderqueer readership, right?

Moorhouse: Yeah. I’m excited to see how her work will be received. I do feel that much of her writing is, in fact, very contemporary around gender. But she wasn’t intellectualizing it. It came out in her voice, which rejected any gender confines without having to announce that she was doing so.

Rumpus: Did you find as a translator that you had to make some harder choices around some of the more dated language, especially in terms of race? Terms that people don’t use anymore?

Moorhouse: There were certainly some words that gave me pause. The word oriental comes up a few times, and this is obviously a word that is dated, perhaps more so in English than in French. What is interesting for me though, is that when I read it in context, I think she is using that word in a way that acknowledges the history behind it, the colonialism, the fetishizing, the exoticizing. For example, Mansour speaks of “oriental suffering,” or of a “narrative with an Oriental woman.” I don’t think, even though she was writing in the 60s at this point, that she uses this word lightly. The way I read it, she uses it to evoke her own nostalgia, or longing for her life in Egypt. And to clarify, when Mansour uses oriental in French, it refers to the Near East. It refers to her own Syrian and Egyptian roots. She never returned to Egypt, so even though she did experience a lot of suffering there, she is still a woman living in exile. This is definitely a challenge of translating older work, especially with an artist who, I think, does not use these words lightly.

Rumpus: Interesting. Because what’s making headlines right now is this political urge to kind of clean up certain language that was used in literature in the past that is hurtful or flat out racist today. So, I still do wonder if there was this urge at all for you to clean up the language?

Moorhouse: I didn’t want the language to be offensive. I would hope that I’ve succeeded with that. I don’t want any dated language to draw attention to itself because that’s not what the poem is meant to do.

Rumpus: But the French is the same. You never changed anything in the French.

Moorhouse: No, I never changed anything in the French. I don’t think I’m allowed to do that. The French is word-for-word.

Rumpus: I think this speaks to its time. And it also—yet again!—points back to the Surrealist problems with women. I mean, sometimes Mansour’s work is so radical and standout, and there are also moments in it when it does feel a bit retrograde. I’m inserting her relationship with Breton in here again because I wonder if she was one of those women who lived as an artist aligning herself with powerful men?

Moorhouse: Well, I think that she would have definitely been outnumbered in those groups, right? I mean, women to men. I don’t know if she was loud, and what her personality was like surrounded by all those men. It’s hard to know. But she did smoke cigars!

Rumpus: Right. That is a very alluring look. Also, she was a mother. I think that’s kind of a big deal in a very male-centric artist’s space.

Moorhouse: Yes, and she was a very doting and overprotective mother. But, you know, even though Mansour may have aligned herself with Breton and other men, I don’t feel like she would have been one to just do things to appease them. And you can see that in her poetry, how she rejects the male gaze that objectifies her. So we can’t just put her in a box or in a category of militant feminist or someone who just goes with the old boys’ club, right?

Rumpus: Yeah, you’re right. She’s both an individual and of her time. In terms of her being a woman, what do you make of her disappearance in the canon? You talk about this in your introduction, her work being perceived as “too much.” Do you think this quality relates to the forgetting of Joyce Mansour?

Moorhouse: Being very familiar with the French culture, I would say yes. I use the word chauvinistic because I think that certain French literary elite have this very precise idea of what “French” literature is, and what “great” literature is. And mostly, it’s been men, White men, who write “great literature” and historically women were allowed to write for children. I think it’s a shame because there are so many Francophone voices that are just so rich, so different. And I think that some in the literary elite just don’t know what to make of these so-called different voices, so they kind of dismiss them. And it’s too bad, because these voices enrich the literary landscape. French literature has been very France-centric, right? Which, obviously, has its roots in colonialism. So even though Mansour was somewhat respected as a Surrealist, the wider French literary establishment very easily could have dismissed her. When I was working on getting some of the rights from one of her publishers—and it’s really hard to get through to them—when I finally had a conversation with them, even they dismissed her! This man said to me, “You know, Joyce Mansour would be nothing without Breton. Without André Breton, there would be no Joyce Mansour.” So even one of her publishers in this day and age still doesn’t take her seriously.

Rumpus: There is this suspicion that Breton created her?

Moorhouse: Yes, and that she’s only recognized to the limited degree that she is because of her affiliation with him.

Rumpus: It feels that this relationship with Breton is really at the crux of a lot for Mansour. I mean, he clearly was incredibly important to her, he was her mentor and she loved him, and I don’t know—these very close artistic relationships they can be difficult for others in the world to understand. Maybe it’s why #metoo resonates differently in France, to be honest. And now I’m thinking of Maïwenn and Luc Besson, which is totally different, but still. . . . When did André Breton die? Was it 1968?

Moorhouse: I think it was 1966. I’m not sure.

Rumpus: Because it’s interesting, I was thinking of Mansour’s 1960s publication White Squares and her last work from the 1980s, Black Holes. Her later work is really kind of dark. My favorite line from one of her late poems is: “The world is a shitting bird.” I mean, I don’t want to say that Breton had an unnatural or too strong of a hold on her or a shitty hold on her, but maybe he did. Maybe her work matured after Breton’s death. Maybe it got even wilder.

Moorhouse: Yeah, I mean, I definitely do see that difference between her earlier work and her later work. It’s not just that the poems in her earlier works are shorter. The later ones are more macabre and her identity is more explicit—both her Jewish identity and her Egyptian identity. Also, Mansour evokes disease and aging and the history of cancer in her family. She died of cancer, like her mother did, and I don’t know if her battle was a short one or drawn out. There is another collection of her poems—prose poems that we couldn’t publish because of copyright—but there’s one about the hospital, and it sounds like it’s her visiting someone in a hospital and it’s very much about the human body falling apart and this industrialized hospital where all bodies are falling apart together.

Rumpus: Her mixing of the sexual body and the dying body is so powerful. I love Mansour’s use of urine, actually. Sometimes, it is this incredibly liberatory thing, like, pissing in the street. And then it’s poisonous, or it’s hedonistic, she’s drinking it like honey. Piss is this ubiquitous substance and act in her work. I love that.

Moorhouse: It’s almost like the soul, your soul comes out in your urine. What else can I say about that?

Rumpus: Nothing. That’s perfect. Your soul is in your urine.

***

Author photo by Selena Phillips Boyle

For most of us, the title The Shining first calls to mind the Stanley Kubrick film, not the Stephen King novel from which it was adapted. Though it would be an exaggeration to say that the former has entirely eclipsed the latter, the enormous difference between the works’ relative cultural impact speaks for itself — as does the resentment King occasionally airs about Kubrick’s extensive reworking of his original story. At the center of both versions of The Shining is a winter caretaker at a mountain resort who goes insane and tries to murder his own family, but in most other respects, the experience of the two works could hardly be more different.

How King’s The Shining became Kubrick’s The Shining is the subject of the video essay above from Tyler Knudsen, better known as CinemaTyler, previously featured here on Open Culture for his videos on such auteurs as Robert Wiene, Jean Renoir, and Andrei Tarkovsky (as well as a seven-part series on Kubrick’s own 2001: A Space Odyssey). It begins with Kubrick’s search for a new idea after completing Barry Lyndon, which involved opening book after book at random and tossing against the wall any and all that proved unable to hold his attention. When it became clear that The Shining, the young King’s third novel, wouldn’t go flying, Kubrick enlisted the more experienced novelist Diane Johnson to collaborate with him on an adaptation for the screen.

Almost all of Kubrick’s films are based on books. As Knudsen explains it, “Kubrick felt that there aren’t many original screenwriters who are a high enough caliber as some of the greatest novelists,” and that starting with an already-written work “allowed him to see the story more objectively.” In determining the qualities that resonated with him, personally, “he could get at the core of what was good about the story, strip away the clutter, and enhance the most brilliant aspects with a profound sense of hindsight.” In no case do the transformative effects of this process come through more clearly than The Shining: Kubrick and Johnson reduced King’s almost 450 dialogue- and flashback-filled pages to a resonantly stark two and a half hours of film that has haunted viewers for four decades now.

“I don’t think the audience is likely to miss the many and self-consciously ‘heavy’ pages King devotes to things like Jack’s father’s drinking problem or Wendy’s mother,” Kubrick once said. Still, anyone can hack a story down: the hard part is knowing what to keep, and even more so what to intensify for maximum effect. Knudsen lists off a host of choices Kubrick and Johnson considered (including showing more Native American imagery, which should please fans of Bill Blakemore’s analysis in “The Family of Man”) but ultimately rejected. The result is a film with an abundance of visual detail, but only enough narrative and character detail to facilitate Kubrick’s aim of “using the audience’s own imagination against them,” letting them fill in the gaps with fears of their own. While his version of The Shining evades nearly all clichés, it does demonstrate the truth of one: less is more.

Related content:

Stanley Kubrick’s Annotated Copy of Stephen King’s The Shining

How Stanley Kubrick Made 2001: A Space Odyssey: A Seven-Part Video Essay

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining Reimagined as Wes Anderson and David Lynch Movies

The Shining and Other Complex Stanley Kubrick Films Recut as Simple Hollywood Movies

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The forecasted rain held off, the poor air quality caused by Canadian wildfires had abated, and the world’s largest Pride parade stepped off without incident in New York City on the final Sunday in June.

It’s grown quite a bit since the last Sunday of June 1970, when Christopher Street Liberation Day March participants paraded from Sheridan Square to Central Park’s Sheep Meadow.

Seeking to commemorate the one year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, when a police raid touched off a riot at the Greenwich Village gay bar, the event’s planners took inspiration from the organized resistance to the Vietnam War and Annual Reminders, a yearly call for equality from the Philadelphia-based Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations.

Parade co-organizer Craig Rodwell imagined a more freewheeling public event involving larger numbers than Annual Reminders, something that could “encompass the ideas and ideals of the larger struggle in which we are engaged—that of our fundamental human rights.”

In the lead up to the parade, Gay Liberation Front News reported that society stacked the deck against openly gay individuals, an observation echoed by a marcher in lesbian activist Lilli M. Vincenz‘s documentary footage, above:

At first I was very guilty, and then I realized that all the things that are taught you, not only by society but by psychiatrists are just to fit you in a mold and I’ve just rejected the mold. And when I rejected the mold, I was happier.

Look carefully for placards from various participating groups, including the Mattachine Societies of Washington and New York, Lavender Menace, the Gay Activists Alliance, a church, and gay student groups at Rutgers and Yale.

Estimates place the crowd at anywhere from 3,000 to 20,000. In addition to marchers, the parade drew plenty of onlookers, some voicing support like a uniformed soldier stationed at Fort Dix who says “Great, man, do your thing!”. Others came prepared to voice their vigorous opposition.

“He’s a closet queen and you can find him in Howard Johnson’s any night,” a marcher cracks when asked his opinion of a counter demonstrator brandishing a sign invoking Sodom and Gomorrah.

Presumably the second part of this marcher’s comment was not intended to signify that the gent in question had a powerful attraction to the venerable Times Square diner’s fried clams, but rather its upstairs neighbor, the all-male Gaiety strip club.

Compared to the flashy festive costumes and booming club music that have become a staple of this millennia’s Pride Marches, 1970’s proceedings were a comparatively modest affair. Marchers chanted in unison, processing uptown in street clothes – hippie-style duds of the period with a couple of square suits and fedoras in the mix.

A clean cut young man in a windbreaker and natty star-spangled tie expressed frank disappointment that Mayor John Lindsay and other political figures had kept their distance.

Younger readers may be taken aback to hear Vincenz asking him how long he had been gay, but gratified when he responds, “I was born homosexual, it’s beautiful.”

By the time the marchers reached the Sheep Meadow, a number of men had shed their shirts. The parade morphed into a pastoral celebration in which revelers can be seen playing Ring Around the Rosie, plucking weeds to decorate each other’s hair, and attempting to break the record for longest kiss.

A man whose bib overalls have been customized with iron-on letters arranged to spell out Stud Farm expresses regret that he spent so many years in the closet.

Co-organizer Foster Gunnison Jr.’s wish was for every queer participant to leave the parade with “a new feeling of pride and self-confidence … to raise the consciences of participating homosexuals-to develop courage, and feelings of dignity and self-worth.”

That first parade’s marshal, Mark Segal, cofounder of Gay Liberation Front, summed it up on the 50th anniversary of the original event:

The march was a reflection of us: out, loud and proud.

Enjoy a glimpse of 2023’s New York City Pride March here.

Via Kottke

Related Content

The Untold Story of Disco and Its Black, Latino & LGBTQ Roots

Different From the Others (1919): The First Gay Rights Movie Ever … Later Destroyed by the Nazis

Sigmund Freud Writes to Concerned Mother: “Homosexuality is Nothing to Be Ashamed Of” (1935)

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

When Kurt Vonnegut reflected on the secret of happiness, he distilled it to “the knowledge that I’ve got enough.” And yet, both as a species and as individuals in an industrialist, materialistic, mechanistic culture, we are living under the tyranny of more — a civilizational cult we call progress. We have forgotten who we would be, and what our world would look like, if instead we lived under the benediction of enough.

How we got here, and what we might do about it, is what photographer, writer, illustrator, and wilderness guide Miriam Körner explores in Fox and Bear (public library) — a love letter to nature disguised as a modern fable of ecological grief and hope, partway between The Iron Giant and The Forest, yet entirely and consummately original, painstakingly illustrated in cut-out dioramas from reused and recycled cardboard, narrated with poetic tenderness and a passion for possibility.

Every day, Fox and Bear went into the forest to gather what there was to gather and to catch what there was to catch.

Day after day, the two friends forage and hunt together, watch the sun set and listen to the birds sing.

Life was good, thought Bear.

Picking berries and mushrooms,

hunting ants and mice,

catching rabbits and birds

kept them busy day after day.

But eventually, these joyful activities turn into tasks and the two friends get seduced by the trap of efficiency — that deadening impulse to optimize and operationalize doing at the expense of being.

As Bear and Fox begin gathering more and more seeds, catching more and more birds, laboring to water the seedlings and feed the birds, they suddenly find themselves with no time to watch the sunset or listen to birdsong.

This is how the allure of automation creeps in — Fox sets about inventing mechanical means of accomplishing the daily tasks, in the hope of liberating more time for leisure: an egg collector, a bird feeder, a water sprinkler, a berry picker.

Instead, the opposite happens as the forest begins to look like an industrial palace evocative of the Scottish philosopher John Macmurray’s cautionary observation that “we worship efficiency and success; and we do not know how to live finely.”

All this enterprise ends up consuming the time for leisure, subsuming the space for joy, affirming Hermann Hesse’s century-old admonition that “the high value put upon every minute of time, the idea of hurry-hurry as the most important objective of living, is unquestionably the most dangerous enemy of joy.”

Every day now, Fox and Bear cut down more trees to burn in the steam engines, so the egg collector could collect eggs and the water sprinkler would water the plants. At night, they filled the bird feeder and fixed the berry picker and built more cages until it was almost sunrise.

As Fox keeps dreaming up bigger and bigger engines, faster and faster machines, Bear finds himself “so tired he had no imagination left.”

Suddenly, he wakes up from the trance of busyness and remembers how lovely it was to simply wander the forest “and gather what there is to gather and catch what there is to catch.”

And, just like that, the two friends abandon the compulsions of progress and return to the elemental joy of simply being alive — creatures among creatures, on a world already perfectly tuned for every creaturely need. We have a finite store of sunsets in a life, after all.

Couple Fox and Bear with the Dalai Lama’s illustrated ethical and ecological philosophy for the next generation, then revisit the forgotten conservation pioneer William Vogt’s roadmap to civilizational survival and Denise Levertov’s stirring poem about our relationship to the natural world.

Illustrations courtesy of Miriam Körner

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

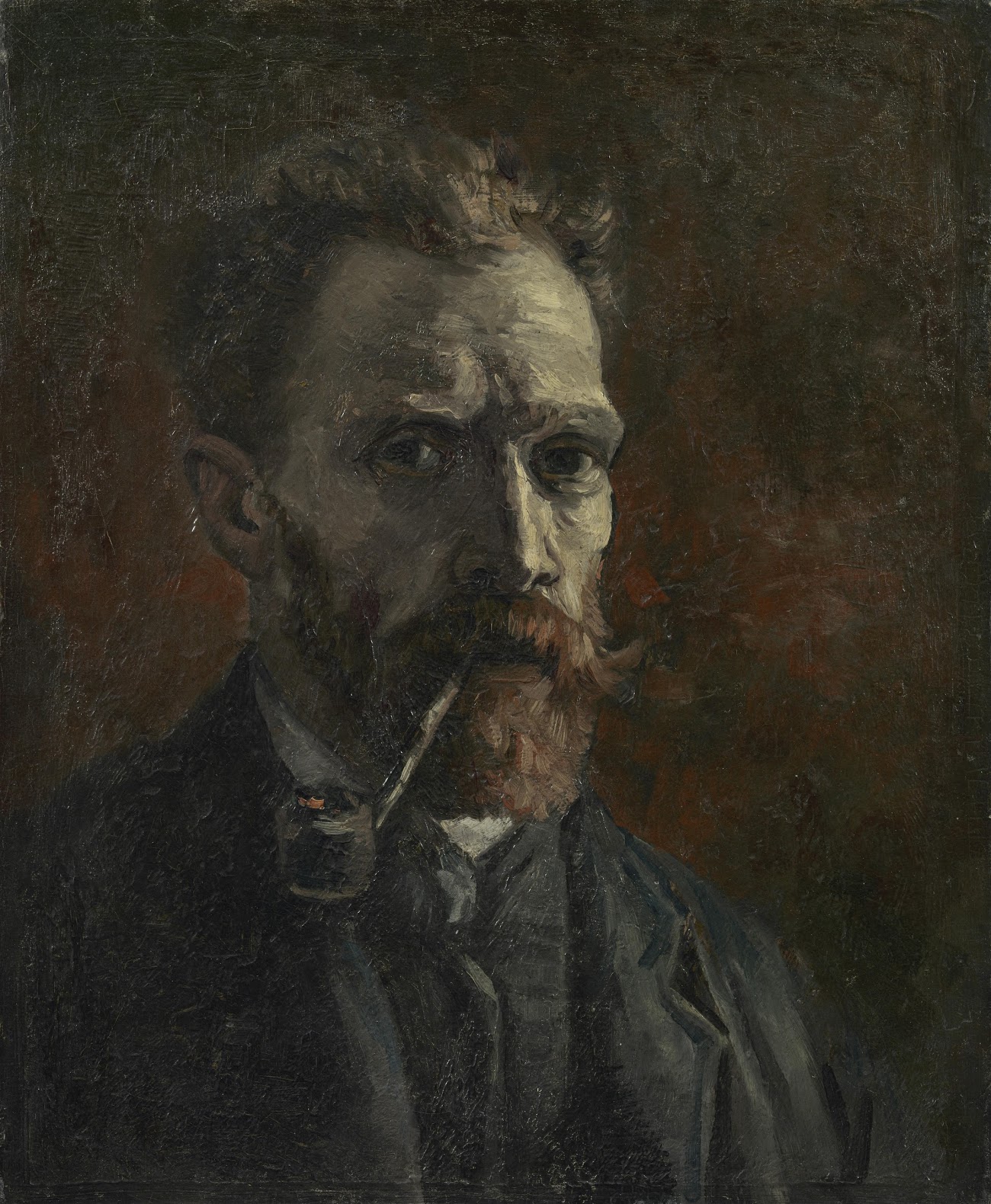

Caravaggio, Self-portrait as the Sick Bacchus. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pasolini’s pen was preternatural in its output. Collected by the publishing house Mondadori in their prestigious Meridiani series, his complete works in the original Italian (excluding private documents such as diaries, and his immense, largely unpublished, epistolary exchanges in various languages) fill ten densely printed volumes. The twenty thousand or so pages of this gargantuan oeuvre suggest that, in the course of his short adult life, Pasolini must have written thousands of words every day, without fail.

Allusions to painting—and to the visual arts more broadly—appear across the full range of Pasolini’s writings, from journalistic essays to poetry and work for theater and film. The intended destination of the textual fragment below, which remained unpublished during Pasolini’s lifetime, remains uncertain. We know, however, that it was most likely penned in 1974. The “characterological” novelty of Caravaggio’s subjects, to which Pasolini alludes in passing, underscores some of the parallels between the two artists’ bodies of work: an eye for the unlikely sacredness of the coarse and squalid; a penchant for boorishness to the point of blasphemy; an attraction to louts and scoundrels of a certain type—the “rough trade,” of homosexual parlance.It is striking, for instance, that some of the nonprofessional actors that Pasolini found in the outskirts of Rome and placed in front of his camera bear an uncanny resemblance to the “new kinds of people” that Caravaggio “placed in front of his studio’s easel,” to quote from the essay presented here. Take Ettore Garofolo, who for a moment in Mamma Roma looks like a tableau vivant of Caravaggio’s Bacchus as a young waiter. Even the illness that ultimately kills that subproletarian character—so often read as a metaphor of the effects of late capitalism on Italy’s post-Fascist society—is born out of an art historical intuition that is articulated in this fragment on Caravaggio’s use of light.

But it was equally an exquisite formal sense—a search after “new forms of realism”—that drew Pasolini to Caravaggio’s work, particularly the peculiar accord struck in his paintings between naturalism and stylization. Pasolini professed to “hate naturalism” and, with some exceptions, avoided the effects of Tenebrism in his cinema. It is, instead, the very artificiality of Caravaggio’s light—a light that belongs “to painting, not to reality”—which earns his admiration.

The Roberto Longhi mentioned below is Pasolini’s former teacher, an art historian at the forefront of Caravaggio studies. It was Longhi who resurrected the painter from a certain obscurity in the twenties, arguing for the consequence of his work to a wider European tradition from Rembrandt and Ribera to Courbet and Manet.

—Alessandro Giammei and Ara H. Merjian

Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio.

The third thing that Caravaggio invented is a membrane that separates both him (the author) and us (the audience) from his characters, still lifes, and landscapes. This membrane, too, is made of light, but of an artificial light proper solely to painting, not to reality—a membrane that transposes the things that Caravaggio painted into a separate universe. In a certain sense, that universe is dead, at least compared to the life and realism with which the things were perceived and painted in the first place, a process brilliantly accounted for by Longhi’s hypothesis that Caravaggio painted while looking at his figures reflected in a mirror. Such were the figures that he had chosen according to a certain realism: neglected errand boys at the greengrocer’s, common women entirely overlooked, et cetera. Though immersed in that realistic light, the light of a specific hour with all its sun and all its shadow, everything in the mirror appears suspended, as if by an excess of truth, of the empirical. Everything appears dead.

I may love, in a critical sense, Caravaggio’s realistic choice to trace the paintable world through characters and objects. Even more critically, I may love the invention of a new light that gives room to immobile events. Yet a great deal of historicism is necessary to grasp Caravaggio’s realism in all its majesty. As I am not an art critic, and see things from a false and flattened historical perspective, Caravaggio’s realism seems rather normal to me, superseded as it was throughout the centuries by other, newer forms of realism. As far as light is concerned, I may appreciate Caravaggio’s invention in its stupendous drama. Yet because of my own aesthetic penchants—determined by who knows what stirrings in my subconscious—I don’t like inventions of light. I much prefer the invention of forms. A new way to perceive light excites me far less than a new way to perceive, say, the knee of a Madonna under her mantle, or the close-up perspective of some saint. I love the invention and the abolition of geometries, compositions, chiaroscuro. In front of Caravaggio’s illuminated chaos, I remain admiring but also, if one sought my strictly personal opinion here, a tad detached. What excites me is his third invention: the luminous membrane that renders his figures separate, artificial, as though reflected in a cosmic mirror. Here, the realist and abject traits of faces appear smoothed into a mortuary characterology; and thus light, though dripping with the precise time of day from which it was plucked, becomes fixed in a prodigiously crystallized machine. The young Bacchus is ill, but so is his fruit. And not only the young Bacchus; all of Caravaggio’s characters are ill. Though they should be vital and healthy as a matter of consequence, their skin is steeped in the dusky pallor of death.

Translated from the Italian by Alessandro Giammei and Ara H. Merjian.

From Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting, to be published by Verso Books in August.

Alessandro Giammei is an assistant professor of Italian studies at Yale University. Il Rinascimento è uno zombie will be published by Einaudi in 2024.

Ara H. Merjian is a professor of Italian studies at New York University. He is the author of Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism. Fragments of Totality: Futurism, Fascism, and the Sculptural Avant-Garde will be published by Yale University Press in 2024.

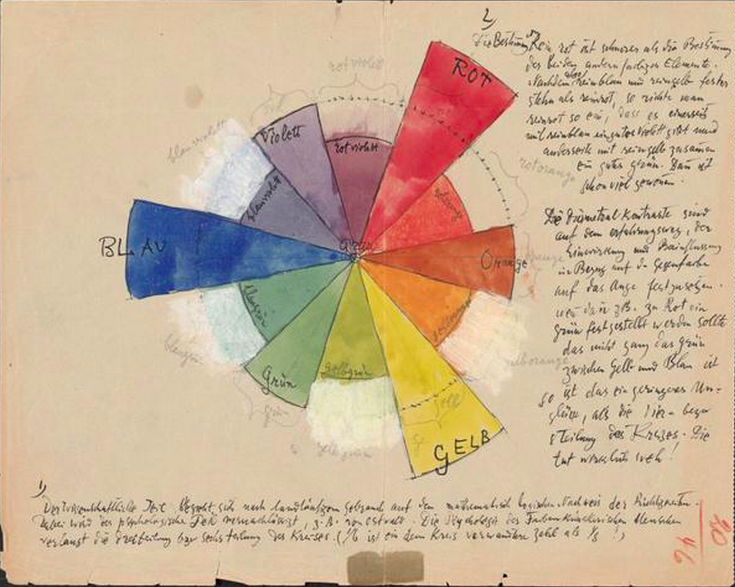

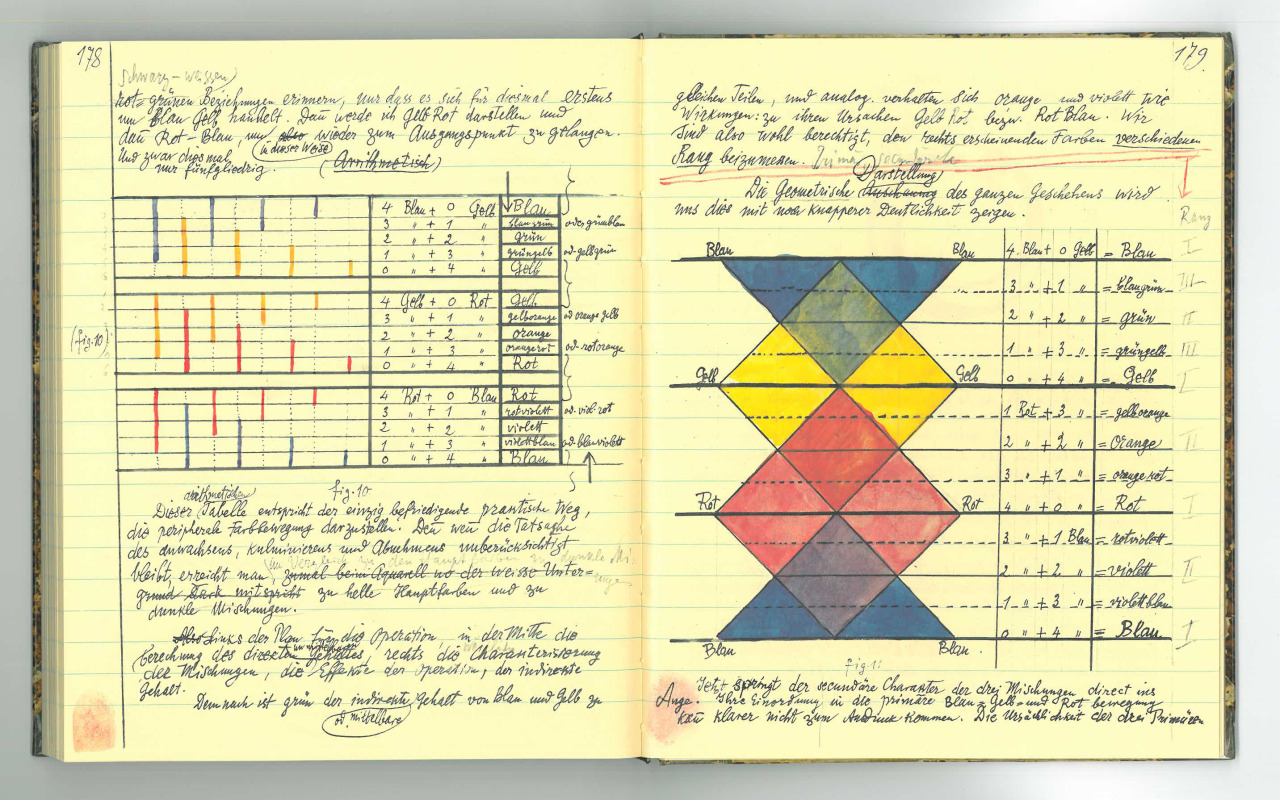

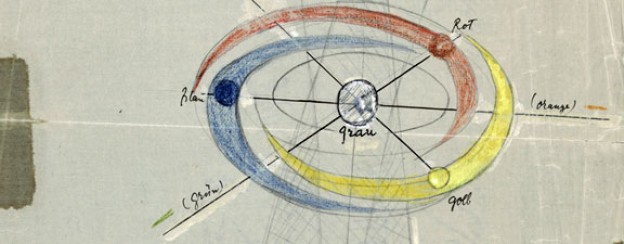

Paul Klee led an artistic life that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, but he kept his aesthetic sensibility tuned to the future. Because of that, much of the Swiss-German Bauhaus-associated painter’s work, which at its most distinctive defines its own category of abstraction, still exudes a vitality today.

And he left behind not just those 9,000 pieces of art (not counting the hand puppets he made for his son), but plenty of writings as well, the best known of which came out in English as Paul Klee Notebooks, two volumes (The Thinking Eye and The Nature of Nature) collecting the artist’s essays on modern art and the lectures he gave at the Bauhaus schools in the 1920s.

“These works are considered so important for understanding modern art that they are compared to the importance that Leonardo’s A Treatise on Painting had for Renaissance,” says Monoskop. Their description also quotes critic Herbert Read, who described the books as “the most complete presentation of the principles of design ever made by a modern artist – it constitutes the Principia Aesthetica of a new era of art, in which Klee occupies a position comparable to Newton’s in the realm of physics.”

More recently, the Zentrum Paul Klee made available online almost all 3,900 pages of Klee’s personal notebooks, which he used as the source for his Bauhaus teaching between 1921 and 1931. If you can’t read German, his extensively detailed textual theorizing on the mechanics of art (especially the use of color, with which he struggled before returning from a 1914 trip to Tunisia declaring, “Color and I are one. I am a painter”) may not immediately resonate with you. But his copious illustrations of all these observations and principles, in their vividness, clarity, and reflection of a truly active mind, can still captivate anybody — just as his paintings do.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, Venmo (@openculture) and Crypto. Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

The Homemade Hand Puppets of Bauhaus Artist Paul Klee

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

When first we start learning a new foreign language, any number of its elements rise up to frustrate us, even to dissuade us from going any further: the mountain of vocabulary to be acquired, the grammar in which to orient ourselves, the details of pronunciation to get our mouths around. In these and all other respects, some languages seem easy, some hard, and others seemingly impossible — those last outer reaches being a specialty of Youtuber Joshua Rudder, creator of the channel NativLang. In the video above, he not only presents us with a few of the rarest sounds — or phonemes, to use the linguistic term — in any language, he also shows us how to make them ourselves.

Several African languages use the phoneme gb, as seen twice in the name of the Ivorian dance Gbégbé. “You might be tempted to go all French on it,” Rudder says, but in fact, you should “bring your tongue up to the soft palate” to make the g sound, and at the same time “close and release your lips” to add the b sound.

Evidently, Rudder pulls it off: “Haven’t heard a foreigner say the gb sound right!” says a presumably African commenter below. From there, the phonemic world tour continues to the bilabial trilled africate and pharyngeals used by the Pirahã people of the Amazon and the whistles used on one particular Canary Island — something like the whistled language of Oaxaca, Mexico previously featured here on Open Culture.

Rudder also includes Oaxaca in his survey, but he finds an entirely different set of rare sounds used in a river town whose residents speak the Mazatec language. “For every one normal vowel you give ’em,” he explains, “they have three for you”: one “modal” variety, one “breathy,” and one “creaky.” He ends the video where he began, in Africa, albeit in a different region of Africa, where he finds some of the rarest phonemes, albeit ones we also might have expected: bilabial clicks, whose speakers “close their tongue against the back of their mouth and also close both lips, but don’t purse them.” Then, “using the tongue, they suck a pocket of air into that enclosed area. Finally, they let go of the lips and out pops a” — well, better to hear Rudder pronounce it. If you can do the same, consider yourself one step closer to readiness for a Khoekhoe immersion course.

Related content:

Speaking in Whistles: The Whistled Language of Oaxaca, Mexico

What English Would Sound Like If It Was Pronounced Phonetically

Why Do People Talk Funny in Old Movies?, or The Origin of the Mid-Atlantic Accent

The Scotch Pronunciation Guide: Brian Cox Teaches You How To Ask Authentically for 40 Scotches

Was There a First Human Language?: Theories from the Enlightenment Through Noam Chomsky

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

We feel our way through life, then rationalize our actions, as if emotion were a shameful scar on the countenance of reason. And yet the more we learn about how the mind constructs the world, the more we see that our experience of reality is a function of our emotionally directed attention and “has something of the structure of love.” Philosopher Martha Nussbaum recognized this in her superb inquiry into the intelligence of emotion, observing that “emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself.”

A century before Nussbaum, the far-seeing Scottish philosopher John Macmurray (February 16, 1891–June 21, 1976) took up these questions in a series of BBC broadcasts and other lectures, gathered in his 1935 collection Reason and Emotion (public library).

Macmurray writes:

We ourselves are events in history. Things do not merely happen to us, they happen through us.

They happen primarily through our emotional lives — the root of our motives beneath the topsoil of reason and rationalization. We suffer primarily because we are so insentient to our own emotions, so illiterate in reading ourselves.

Three decades before James Baldwin marveled at how “you think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read,” Macmurray considers the universal resonance of our emotional confusion, which binds us to each other and makes our responsibility for our own lives a responsibility to our collective flourishing:

All of us, if we are really alive, are disturbed now in our emotions. We are faced by emotional problems that we do not know how to solve. They distract our minds, fill us with misgiving, and sometimes threaten to wreck our lives. That is the kind of experience to which we are committed. If anyone thinks they are peculiar to the difficulties of his own situation, let him… talk a little about them to other people. He will discover that he is not a solitary unfortunate. We shall make no headway with these questions unless we begin to see them, and keep on seeing them, not as our private difficulties but as the growing pains of a new world of human experience. Our individual tensions are simply the new thing growing through us into the life of mankind. When we see them steadily in this universal setting, then and then only will our private difficulties become really significant. We shall recognize them as the travail of a new birth for humanity, as the beginning of a new knowledge of ourselves and of God.

At the heart of this recognition, this reorientation to our own inner lives, lies what Macmurray calls “emotional reason” — a capacity through which we “develop an emotional life that is reasonable in itself, so that it moves us to forms of behaviour which are appropriate to reality.” The absence of this capacity contributes both to our alienation from life and to our susceptibility to dangerous delusion. Its development requires both a willingness to feel life deeply and what Bertrand Russell called “the will to doubt.” Macmurray writes:

The main difficulty that faces us in the development of a scientific knowledge of the world lies not in the outside world but in our own emotional life. It is the desire to retain beliefs to which we are emotionally attached for some reason or other. It is the tendency to make the wish father to the thought. .. If we are to be scientific in our thoughts… we must be ready to subordinate our wishes and desires to the nature of the world… Reason demands that our beliefs should conform to the nature of the world, not the nature of our hopes and ideals.

In consonance with Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran’s insightful insistence on the courage to disillusion yourself, Macmurray adds:

The strength of our opposition to the development of reason is measured by the strength of our dislike of being disillusioned. We should all admit, if it were put to us directly, that it is good to get rid of illusions, but in practice the process of disillusionment is painful and disheartening. We all confess to the desire to get at the truth, but in practice the desire for truth is the desire to be disillusioned. The real struggle centres in the emotional field, because reason is the impulse to overcome bias and prejudice in our own favour, and to allow our feelings and desires to be fashioned by things outside us, often by things over which we have no control. The effort to achieve this can rarely be pleasant or flattering to our self-esteem. Our natural tendency is to feel and to believe in the way that satisfies our impulses. We all like to feel that we are the central figure in the picture, and that our own fate ought to be different from that of everybody else. We feel that life should make an exception in our favour. The development of reason in us means overcoming all this. Our real nature as persons is to be reasonable and to extend and develop our capacity for reason. It is to acquire greater and greater capacity to act objectively and not in terms of our subjective constitution. That is reason, and it is what distinguishes us from the organic world, and makes us super-organic.

And yet reason, Macmurray argues, is “primarily an affair of emotion” — a paradoxical notion he unpacks with exquisite logical elegance:

All life is activity. Mere thinking is not living. Yet thinking, too, is an activity, even if it is an activity which is only real in its reference to activities which are practical. Now, every activity must have an adequate motive, and all motives are emotional. They belong to our feelings, not our thoughts.

[…]

It is extremely difficult to become aware of this great hinterland of our minds, and to bring our emotional life, and with it the motives which govern our behaviour, fully into consciousness.

This difficulty is precisely what makes us so maddeningly opaque to ourselves, and what makes emotional reason so urgent a necessity in understanding ourselves — something only possible, in a further paradox, when we step outside ourselves:

The real problem of the development of emotional reason is to shift the centre of feeling from the self to the world outside. We can only begin to grow up into rationality when we begin to see our own emotional life not as the centre of things but as part of the development of humanity.

In a sentiment evocative of E.E. Cummings’s wonderful meditation on the courage to feel for yourself, Macmurray adds:

There can be no hope of educating our emotions unless we are prepared to stop relying on other people’s for our judgements of value. We must learn to feel for ourselves even if we make mistakes.

An epoch before neuroscience uncovered how the life of the body gives rise to emotion and consciousness, Macmurray echoes Willa Cather’s insistence on the life of the senses as the key to creativity and vitality, and writes:

Our sense-life is central and fundamental to our human experience. The richness and fullness of our lives depends especially upon the richness and fullness, upon the delicacy and quality of our sense-life.

[…]

Living through the senses is living in love. When you love anything, you want to fill your consciousness with it. You want to affirm its existence. You feel that it is good and that it should be in the world and be what it is. You want other people to look at it and enjoy it too. You want to look at it again and again. You want to know it, to know it better and better, and you want other people to do the same. In fact, you are appreciating and enjoying it for itself, and that is all that you want. This kind of knowledge is primarily of the senses. It is not of the intellect. You don’t want merely to know about the object; often you don’t want to know about it at all. What you do want is to know it. Intellectual knowledge tells us about the world. it gives us knowledge about things, not knowledge of them. It does not reveal the world as it is. Only emotional knowledge can do that.

Emotional reason thus becomes the pathway to wholeness, to integration of the total personality — a radical achievement in a culture that continually fragments and fractures us:

The fundamental element in the development of the emotional life is the training of this capacity to live in the senses, to become more and more delicately and completely aware of the world around us, because it is a good half of the meaning of life to be so. It is training in sensitiveness… If we limit awareness so that it merely feeds the intellect with the material for thought, our actions will be intellectually determined. They will be mechanical, planned, thought-out. Our sensitiveness is being limited to a part of ourselves — the brain in particular — and, therefore, we will act only with part of ourselves, at least so far as our actions are consciously and rationally determined. If, on the other hand, we live in awareness, seeking the full development of our sensibility to the world, we shall soak ourselves in the life of the world around us; with the result that we shall act with the whole of ourselves.

A generation after William James made the then-radical assertion that “a purely disembodied human emotion is a nonentity,” and an epoch before science began illuminating how our bodies and our minds conspire in emotional experience, Macmurray considers what the achievement of emotional reason requires:

We have to learn to live with the whole of our bodies, not only with our heads… The intellect itself cannot be a source of action… Such action can never be creative, because creativeness is a characteristic which belongs to personality in its wholeness, acting as a whole, and not to any of its parts acting separately.

This wakefulness to the sensorium of life, he argues, is not only the root of emotional reason but the root of creativity:

If we allow ourselves to be completely sensitive and completely absorbed in our awareness of the world around, we have a direct emotional experience of the real value in the world, and we respond to this by behaving in ways which carry the stamp of reason upon them in their appropriateness and grace and freedom. The creative energy of the world absorbs us into itself and acts through us. This, I suppose, is what people mean by “inspiration.”

And yet we can’t be selectively receptive to beauty and wonder — those rudiments of inspiration — without being receptive to the full spectrum of reality, with all its terrors and tribulations. Our existential predicament is that, governed by the reflex to spare ourselves pain, we blunt our sensitivity to life, thus impoverishing our creative vitality and our store of aliveness. Macmurray writes:

The reason why our emotional life is so undeveloped is that we habitually suppress a great deal of our sensitiveness and train our children from the earliest years to suppress much of their own. It might seem strange that we should cripple ourselves so heavily in this way… We are afraid of what would be revealed to us if we did not. In imagination we feel sure that it would be lovely to live with a full and rich awareness of the world. But in practice sensitiveness hurts. It is not possible to develop the capacity to see beauty without developing also the capacity to see ugliness, for they are the same capacity. The capacity for joy is also the capacity for pain. We soon find that any increase in our sensitiveness to what is lovely in the world increases also our capacity for being hurt. That is the dilemma in which life has placed us. We must choose between a life that is thin and narrow, uncreative and mechanical, with the assurance that even if it is not very exciting it will not be intolerably painful; and a life in which the increase in its fullness and creativeness brings a vast increase in delight, but also in pain and hurt.

The development of emotional reason, Macmurray argues, is the development of our highest human nature and requires “keeping as fully alive to things as they are, whether they are pleasant or unpleasant, as we possibly can.” It requires, above all, being unafraid to feel, for that is the fundament of aliveness. He writes:

The emotional life is not simply a part or an aspect of human life. It is not, as we so often think, subordinate, or subsidiary to the mind. It is the core and essence of human life. The intellect arises out of it, is rooted in it, draws its nourishment and sustenance from it, and is the subordinate partner in the human economy. This is because the intellect is essentially instrumental. Thinking is not living. At its worst it is a substitute for living; at its best a means of living better… The emotional life is our life, both as awareness of the world and as action in the world, so far as it is lived for its own sake. Its value lies in itself, not in anything beyond it which it is a means of achieving.

[…]

The education of the intellect to the exclusion of the education of the emotional life… will inevitably create an instrumental conception of life, in which all human activity will be valued as a means to an end, never for itself. When it is the persistent and universal tendency in any society to concentrate upon the intellect and its training, the result will be a society which amasses power, and with power the means to the good life, but which has no correspondingly developed capacity for living the good life for which it has amassed the means… We have immense power, and immense resources; we worship efficiency and success; and we do not know how to live finely. I should trace the condition of affairs almost wholly to our failure to educate our emotional life.

In the remainder of the thoroughly revelatory Reason and Emotion, Macmurray goes on to explore the role of art and religion in human life as “the expressions of reason working in the emotional life in search of reality,” the benedictions of friendship, and the fundaments of an emotional education that allows us to discover the true values in life for ourselves. Complement it with Dostoyevsky on the heart, the mind, and how we come to know truth and Bruce Lee’s unpublished writings on reason and emotion, then revisit Anaïs Nin on why emotional excess is essential for creativity.

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

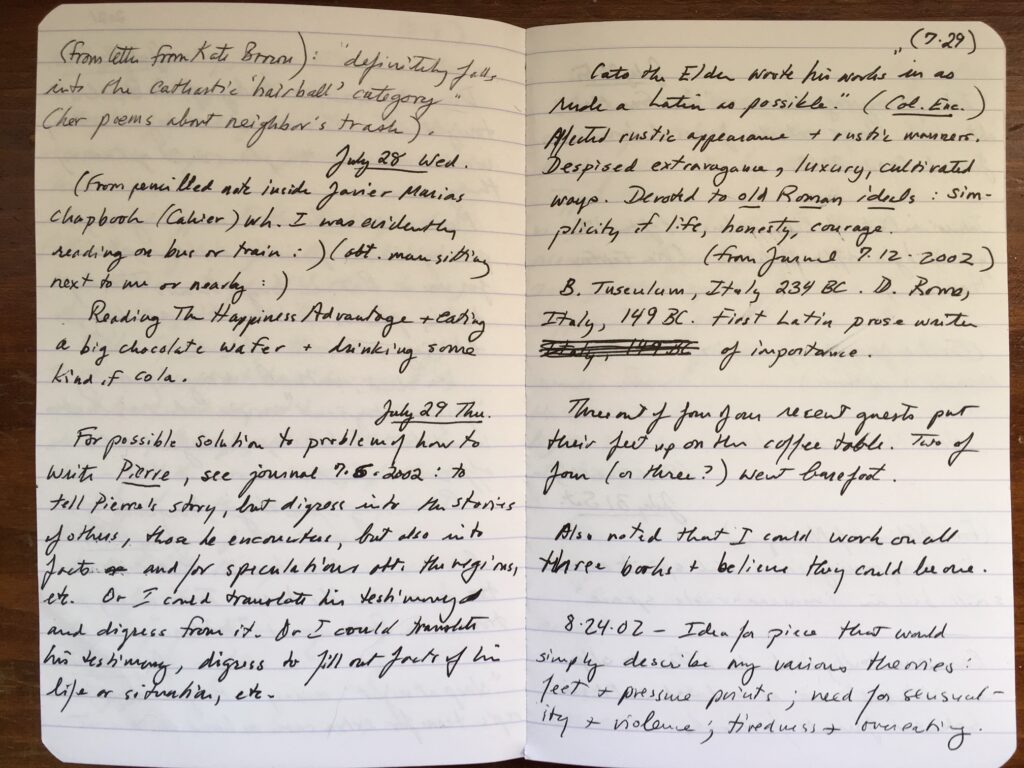

In these pages, written in 2021, I seem to have been looking back at earlier notes and journals. The story of Pierre—a French shepherd—is a project imagined decades ago that I still have not given up on. My “theories” are also still interesting to me: for instance, that maybe certain people are more inclined to violence when there is less sensuality of other kinds in their lives.

Lydia Davis’s story collection Our Strangers will be published in fall 2023 by Bookshop Editions. Selections from her 1996 journals appear in the Review‘s new Summer issue, no. 244.

The earliest known works of Japanese art date from the Jōmon period, which lasted from 10,500 to 300 BC. In fact, the period’s very name comes from the patterns its potters created by pressing twisted cords into clay, resulting in a predecessor of the “wave patterns” that have been much used since. In the Heian period, which began in 794, a new aristocratic class arose, and with it a new form of art: Yamato-e, an elegant painting style dedicated to the depiction of Japanese landscapes, poetry, history, and mythology, usually on folding screens or scrolls (the best known of which illustrates The Tale of Genji, known as the first novel ever written).

This is the beginning of the story of Japanese art as told in the half-hour-long Behind the Masterpiece video above. It continues in 1185 with the Kamakura period, whose brewing sociopolitical turmoil intensified in the subsequent Nanbokucho period, which began in 1333. As life in Japan became more chaotic, Buddhism gained popularity, and along with that Indian religion spread a shift in preferences toward more vital, realistic art, including celebrations of rigorous samurai virtues and depictions of Buddhas. In this time arose the form of sumi-e, literally “ink picture,” whose tranquil monochromatic minimalism stands in the minds of many still today for Japanese art itself.

Japan’s long history of fractiousness came to an end in 1568, when the feudal lord Oda Nobunaga made decisive moves that would result in the unification of the country. This began the Azuchi-Momoyama period, named for the castles occupied by Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The castle walls were lavishly decorated with large-scale paintings that would define the Kanō school. Traditional Japan itself came to an end in the long, and military-governed Edo period, which lasted from 1615 to 1868. The stability and prosperity of that era gave rise to the best-known of all classical Japanese art forms: kabuki theatre, haiku poetry, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

With their large market of merchant-class buyers, ukiyo-e artists had to be prolific. Many of their works survive still today, the most recognizable being those of masters like Utamaro, Hokusai, and Hiroshige. Here on Open Culture, we’ve previously featured Hokusai’s series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji as well as its famous installment The Great Wave Off Kanagawa. As Japan opened up to the west from the middle of the nineteenth century, the various styles of ukiyo-e became prime ingredients of the Japonisme trend, which extended the influence of Japanese art to the work of major Western artists like Degas, Manet, Monet, van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 opened the long-isolated Japan to world trade, re-established imperial rule, and also, for historical purposes, marked the country’s entry into modernity. This inspired an explosion of new artistic techniques and movements including Yōga, whose participants rendered Japanese subject matter with European techniques and materials. Born early in the Shōwa era but still active in her nineties, Yayoi Kusama now stands (and in Paris, at enormous scale in statue form) as the most prominent Japanese artist in the world. The rich psychedelia of her work belongs obviously to no single culture or tradition — but then again, could an artist of any other country have come up with it?

Related content:

Download 215,000 Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters Spanning the Tradition’s 350-Year History

How to Paint Like Yayoi Kusama, the Avant-Garde Japanese Artist

The Entire History of Japan in 9 Quirky Minutes

The History of Western Art in 23 Minutes: From the Prehistoric to the Contemporary

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Archaeologists digging in Pompeii have unearthed a fresco containing what may be a “distant ancestor” of the modern pizza. The fresco features a platter with wine, fruit, and a piece of flat focaccia. According to Pompeii archaeologists, the focaccia doesn’t have tomatoes and mozzarella on top. Rather, it seemingly sports “pomegranate,” spices, perhaps a type of pesto, and “possibly condiments”–which is just a short hop, skip and a jump away to pizza.

Found in the atrium of a house connected to a bakery, the finely-detailed fresco grew out of a Greek tradition (called xenia) where gifts of hospitality, including food, are offered to visitors. Naturally, the fresco was entombed (and preserved) for centuries by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, Venmo (@openculture) and Crypto. Thanks!

Related Content

Explore the Roman Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, the Oldest Known Cookbook in Existence