— Our initial 2024 Electoral College ratings start with just four Toss-up states.

— Democrats start with a small advantage, although both sides begin south of what they need to win.

— We consider a rematch of the 2020 election — Joe Biden versus Donald Trump — as the likeliest matchup, but not one that is set in stone.

Democrats start closer to the magic number of 270 electoral votes in our initial Electoral College ratings than Republicans. But with few truly competitive states and a relatively high floor for both parties, our best guess is yet another close and competitive presidential election next year — which, if it happened, would be the sixth such instance in seven elections (with 2008 as the only real outlier).

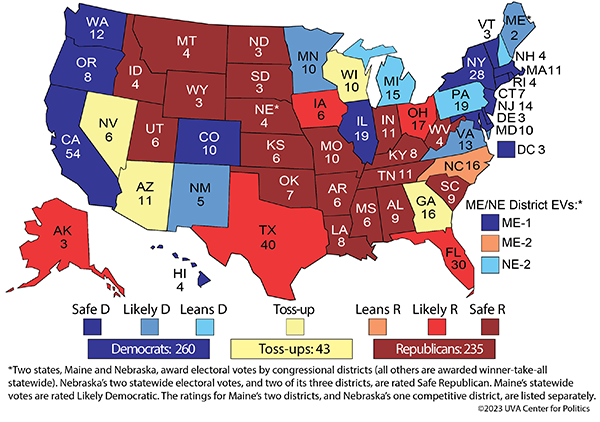

Map 1 shows these initial ratings. We are starting 260 electoral votes worth of states as at least leaning Democratic, and 235 as at least leaning Republican. The four Toss-ups are Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin — the three closest states in 2020 — along with Nevada, which has voted Democratic in each of the last four presidential elections but by closer margins each time (it is one of the few states where Joe Biden did worse than Hillary Clinton, albeit by less than a tenth of a percentage point). That is just 43 Toss-up electoral votes at the outset. Remember that because of a likely GOP advantage in the way an Electoral College tie would be broken in the U.S. House, a 269-269 tie or another scenario where no candidate won 270 electoral votes would very likely lead to a Republican president. So Democrats must get to 270 electoral votes while 269 would likely suffice for Republicans, and there are plausible tie scenarios in the Electoral College.

For the purposes of these ratings, we are considering a rematch of the 2020 election — Joe Biden versus Donald Trump — as the likeliest matchup, but not one that is set in stone.

Despite a multitude of weaknesses, such as an approval rating in just the low 40s and widespread concern about his age and ability to do the job, Biden does not have credible opposition within his own party, drawing only fringe challengers Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Marianne Williamson. It may be that Biden could or should have drawn a stronger challenger, and maybe something happens that entices that kind of challenger into the race. But as of now, Biden appears to be on course to renomination.

Trump faces legitimate legal problems, specifically following his recent indictment over serious allegations that he improperly retained highly sensitive government documents. However, we would never presume an actual guilty verdict in this or another case until it actually happens — nor are we even sure a guilty verdict would prevent Trump’s renomination. It may be that the weight of Trump’s problems gradually reduces his level of support over the course of this calendar year leading into next year’s primaries, allowing a rival to consolidate the non-Trump portion of the party and really push him in the primaries. Or maybe Trump is compelled to take some sort of plea deal that involves him leaving the race. Those caveats aside, we see a party that is still broadly comfortable with Trump as its nominee. Until that changes, he’s the favorite.

It has now been more than a month since Trump’s leading GOP rival, Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL), entered the race. As best we can tell, he has gotten no real “bump” from becoming an official candidate — if anything, DeSantis’s polling position was stronger several months ago than it is today. Meanwhile, the field has gotten bigger, further splintering the non-Trump support while the former president remains as a clear plurality (or even majority) leader in national and state-level polling. This matters in a nominating contest in which even a plurality leader in a given state can end up getting the lion’s share or all of its delegates (as we saw with Trump in 2016).

For our general election outlook, we are not taking current polling much into account right now. Biden’s national polling right now is probably worse than what our ratings reflect: Different polls show either Biden ahead by a little or Trump ahead by a little nationally, and about a tie in aggregate per RealClearPolitics’s average. We believe Biden would do better than that, at least in the national popular vote, against Trump: Trump lost the popular vote twice, and we doubt he would be a stronger candidate in 2024 than he was in 2016 or 2020. The last time Trump was on the general election ballot was prior to the Jan. 6, 2021 storming of the Capitol, an event that can now be used effectively against him in a general election setting. We just saw that in the 2022 election, several candidates who were tied to Trump running in key states — such as Kari Lake and Blake Masters in Arizona, Herschel Walker in Georgia, several election-denying candidates in other statewide races across the nation, etc. — underperformed the electoral environment. Midterms are not presidential elections, and this does not necessarily mean Trump can’t win — he certainly could, and our ratings reflect that possibility. But the actual results from recent elections, which suggested significant problems for Trump, seem to be a better guide than off-year polling.

We also are not really taking third-party voting into account as of now, although one could imagine the third party vote, whatever size it is, hurting the Democratic nominee more than the GOP nominee. The Green Party nominee, who might be left-wing intellectual Cornel West, could hurt Biden from the left, while a potential candidate backed by the group No Labels could provide an outlet for moderate/conservative voters. However, we do think it’s likely that any third-party candidate will poll better than they perform, and that the ultimate third party vote does not seem likely to be large (perhaps bigger than 2020’s 2% of the total, but likely not reaching 2016’s 6%). Still, that may matter in a close race, so it is a very important factor to watch.

We have previously noted that Biden’s chances in the next election are very contingent on who the GOP decides to nominate as his opponent. As of right now, that person appears likeliest to be Donald Trump. That certainly doesn’t make Biden a shoo-in next year, but it does make him better positioned to win, which is reflected in our ratings.

Let’s take a look at some state-level details of our initial Electoral College ratings:

— Democrats start with 191 Safe electoral votes, while Republicans start with just 122. However, if you combine the Safe and Likely columns, the effective “floor” for both parties is essentially identical: 221 for Democrats, and 218 for Republicans. Texas is one of a handful of important states (Arizona and Georgia are a couple of others) that very clearly have trended Democratic in the Trump era. But Texas is still a Republican-leaning state, as its big urban areas have not quite gotten blue enough to make up for how red its lesser-populated places are. Other Likely Republican states Florida, Iowa, and Ohio have all moved right in the Trump era. Alaska also appears here as Likely Republican as its GOP lean has eroded in recent years, but it’s also still clearly in the GOP column, and it’s included here more as a curiosity than anything else.

— We suspect the rating that might spur the most disagreement is starting Pennsylvania as Leans Democratic, as opposed to a Toss-up. It’s also the one that, internally, we are the most conflicted about. On one hand, Pennsylvania only voted for Biden by a little over a point in 2020 after backing Trump by less than a point in 2016. That basic fact argues for Toss-up. But we also think Biden may have a bit more room to grow in vote-rich southeast Pennsylvania against Trump, which could help protect his narrow edge as Republicans try to squeeze even more of a margin out of the state’s white rural and small-town areas. Certainly Democrats did great in Pennsylvania in 2022, although we don’t necessarily view that as predictive — Democrats also did well in the 2018 statewide races, but that didn’t prevent the state from being close in 2020. If you believe we’re giving an unreasonable benefit of the doubt to Democrats in Pennsylvania, consider that we may be doing the same to Republicans in North Carolina, a state that was Trump’s closest victory in 2020. We also may be giving the GOP a benefit of the doubt by listing Nevada as a Toss-up instead of as Leans Democratic, given the Democrats’ frequent ability to pull out close victories in the state. But Democrats should be concerned that this working-class state’s center of votes, Clark County (Las Vegas), is getting more competitive as opposed to getting more Democratic.

— Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin seem like fairly clear-cut Toss-ups, given how close they were in 2020 (each was decided by less than a point). But there’s a world in which the realigning patterns we’ve seen in the Trump years, in which big metro areas like Phoenix and Atlanta are getting bluer, push their states (Arizona and Georgia) from a reddish shade of purple to a bluish shade, and that Pennsylvania ends up being closer for president than those states are. Who the GOP nominates will play a role here — maybe a non-Trump nominee ends up being a better fit for the party in the Sun Belt, which would solidify Arizona and Georgia as Toss-ups or maybe even push them back to the Republicans. Wisconsin, meanwhile, may be the purest Toss-up on the whole map: Its presidential margin was below a point in four of the last six elections.

— In our 2020 ratings — when we ultimately missed just one state, North Carolina — we started Michigan out as Leans Democratic, a decision that paid off, as Biden won the state by nearly 3 points after it surprisingly backed Trump in 2016. It remains Leans Democratic here, along with New Hampshire, which has long been considered a swing state but seems to have settled left of center. The GOP position on abortion, in particular, seems like a considerable problem in these states (one could apply this argument to Pennsylvania too, among other places).

— Maine and Nebraska, the two states that award electoral votes at the congressional-district level, have unique ratings. Nebraska’s two statewide electoral votes and two of its three districts are Safe Republican, but the Omaha-based NE-2 voted for Biden by about a half-dozen points in 2020, and we are rating it as Leans Democratic to start. Meanwhile, Maine’s northern 2nd District backed Trump by about a half-dozen points in 2020 and it starts as Leans Republican. The two statewide electoral votes are rated as Likely Democratic — Minnesota, New Mexico, and Virginia are also in that category — and the very Democratic 1st District of Maine starts as Safe Democratic.

We have previously noted that only seven states were decided by less than three points in 2020: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. This represents the real battlefield: Particularly if the race is a Biden vs. Trump redux, we would be surprised if any other state flipped from 2020 outside of this group.

Even then, we’re not even sure that all of these seven states are truly in doubt. After all, we’re starting three of the seven in the Leans category (Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania).

This all underscores the reality that despite the nation being locked in a highly competitive era of presidential elections, the lion’s share of the individual states are not competitive at all.

| Dear Readers: In the latest edition of our Politics is Everything podcast, the Crystal Ball’s J. Miles Coleman, Kyle Kondik, and Carah Ong Whaley discuss the results from Tuesday night’s Virginia state legislative primaries and look ahead to the closely-contested battle for control of both chambers coming up this fall. Listen and subscribe here or wherever you get your podcasts.

In today’s Crystal Ball, Senior Columnist Louis Jacobson previews another set of key state-level races for this year and next: attorneys general and secretaries of state. — The Editors |

— The once low-profile contests for attorney general and secretary of state have become increasingly important for driving policy outcomes in the states, particularly in setting the rules for how elections are run.

— The current campaign cycle doesn’t promise quite as much drama as there was in 2022, when several key presidential battleground states played host to tight contests between Republicans aligned with former President Donald Trump and more mainstream Democrats.

— For the current 2023-2024 cycle, we are starting our handicapping by assigning 18 of the 23 races to either the Safe Republican or the Safe Democratic category. Still, a number of these states will undergo wide-open primaries with different ideological flavors of candidates. And in the general election, we see three races as highly competitive: the attorney general and secretary of state races in North Carolina and the AG race in Pennsylvania.

The midterm election of 2022 was an unusually pivotal one for attorney general and secretary of state contests. There was a surplus of races between election-denying Republicans and more mainstream Democrats in such pivotal presidential battleground states as Arizona, Michigan, and Nevada. In our final pre-election handicapping of the 2022 cycle, we rated 12 of the 30 attorney general races and 16 of the 27 secretary of state races as competitive, meaning they were categorized either as Toss-ups or as leaning toward the Democrats or the Republicans.

The current campaign cycle isn’t promising quite as much drama: All told, 18 out of the 23 races on tap start out as either Safe Republican or Safe Democratic in our rankings.

Still, these contests will be important, because attorneys general can file lawsuits with far-reaching policy impact and because secretaries of state oversee the election process (in most states, anyway).

In the 2023-2024 election cycle, at least 6 of the 13 AG races and at least 4 of the 10 secretary of state races will be open seats, often because the incumbent is running for governor — a sign of how these lower-profile offices can serve as important political stepping stones.

Especially in states with heavily Republican leanings, these open-seat races are poised to involve a number of highly competitive primaries. In many cases, these primaries will pit more pragmatic Republicans against more aggressively populist ones. The type of nominee that emerges victorious could have a tangible impact on policy in these states, because those states’ partisanship makes it hard for Democrats to win a general election.

Meanwhile, the key matchups for the 2024 general election promise to be the AG and secretary of state races in North Carolina and the AG contest in Pennsylvania. (Pennsylvania’s secretary of state is appointed by the governor and confirmed by the state Senate rather than elected.) Both states will simultaneously be serving as presidential battlegrounds.

In the meantime, the races for both AG and secretary of state in Kentucky — which will be held later this year — bear watching, with Democrats nominating credible candidates. But because this is heavily red Kentucky, the GOP remains favored to hold both.

Here’s a rundown of each race for AG and secretary of state in the current two-year cycle, based on multiple interviews with political observers, both in the states and nationally. As in the past, we have rated contests in descending order, from most likely to be won by the Republicans to most likely to be won by the Democrats, including within each rating category (Safe Republican, Likely Republican, Leans Republican, Toss-up, Leans Democratic, Likely Democratic, and Safe Democratic). We’ll update these ratings periodically as the contests develop.

First, we’ll start with the three states that vote in 2023. Then we’ll move to the larger number of states that will be voting in 2024.

Louisiana: Open (Jeff Landry, R, is running for governor)

Louisiana’s office of attorney general is opening up this year as Landry runs for governor. That high-stakes race for governor, in which Landry is a leading contender, has significantly overshadowed the battle to fill the office he’s giving up.

Louisiana has an all-party primary on Oct. 14. If no one gets a majority, there will be a runoff on Nov. 18. In many such races in the past, a Democratic candidate has secured one of the two runoff slots. But in the AG contest, no Democrat has emerged yet, and the party’s bench in this solidly red state is thin. So the runoff, if there is one, might come down to what flavor of Republican voters want.

Landry’s top deputy, Solicitor General Liz Murrill, is the most conservative candidate in the race as well as the best funded. In addition to being closely aligned with the polarizing Landry, Murrill was previously a top legal advisor to then-Gov. Bobby Jindal (R), who was unpopular when he left office. Murrill was also widely seen as bungling an abortion case before the U.S. Supreme Court, leading to a loss when Chief Justice John Roberts sided with the four liberals in the case (this was prior to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death in 2020).

Murrill’s leading opponent is GOP state Rep. John Stefanski, who is considered more moderate and is well-liked by state insiders for his even-handed stewardship of the House committee that oversees redistricting. Another Republican running is former prosecutor Marty Maley of Baton Rouge, who finished fifth in the 2015 primary.

Murrill could run strong in an off-year election without a well-known and popular Democrat at the top of the ticket. If no Democrat enters the race and Stefanski makes the runoff, he would have a chance of winning, if he can nail down support from Democrats and establishment Republicans. But it’s unclear how much Stefanski would actively court Democratic votes in that scenario, at the risk of alienating Republicans. And there’s still time for a Democrat to get in the race, which would call into question that strategy.

Mississippi (Republican Lynn Fitch)

Fitch is seeking her second term as attorney general. The Mississippi attorney general’s office was the last statewide office that Democrats controlled in the state; Jim Hood gave it up to make an unsuccessful bid for governor in 2019, and Fitch flipped the open seat in the general election that year. But while Democrats are pleased with their challenger — Greta Kemp Martin, the litigation director of Disability Rights Mississippi — and while they see an opening with corruption allegations against former GOP Gov. Phil Bryant and former NFL quarterback Brett Favre, the Democrats’ chances of winning the AG’s office back this year against an incumbent Republican seem small.

Kentucky: Open (Daniel Cameron, R, is running for governor)

Like Republican gubernatorial candidate Cameron, GOP attorney general nominee Russell Coleman has one foot in the camp of Senate Minority Leader (and Kentucky Republican godfather) Mitch McConnell as well as one foot in the camp of former President Donald Trump. Coleman served as legal counsel to McConnell while also receiving Trump’s appointment to serve as U.S. attorney for Kentucky’s western district.

Coleman’s background in rural Kentucky and his tough-on-crime approach should serve him well in the general election. In a poll by the Republican firm Cygnal, Coleman led his Democratic opponent by double digits even though the same poll showed Cameron in a dead heat with incumbent Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear.

However, many voters in the poll were undecided on the AG race, and Democrat Pamela Stevenson brings a unique personal background to the contest. In addition to serving in the state House, Stevenson spent 27 years in the Air Force, including extensive legal experience as a judge advocate general. Her campaign logo features her rank of colonel in a larger font size than her last name.

Stevenson, a Black Democrat, is running to succeed Cameron, a Black Republican. But geography could be a problem (she’s based in Louisville, a region that has often produced losing statewide Democratic candidates) and passionate speeches from the floor of the state House may provide Republicans with campaign fodder. If Stevenson catches fire, this race’s rating could shift, but for now, given the state’s red tint, we’re starting it at Likely Republican.

Mississippi (Republican Michael Watson)

Watson, elected in 2019, is seeking a second term and should easily win it. He faces Democrat Shuwaski Young, a political organizer and former federal Department of Homeland Security staffer. He ran for Congress against Rep. Michael Guest in 2022, winning only 29% of the vote in the solidly Republican district.

Louisiana: Open seat (Kyle Ardoin is retiring)

Incumbent Republican Kyle Ardoin bowed out of seeking reelection to a second full term, citing the “pervasive lies” of election deniers.

The GOP has a sizable field seeking to succeed him. One contender is Clay Schexnayder, a mechanic and race-car driver who is term-limited in the legislature after becoming the surprise compromise choice for House Speaker in 2020. He is well-known, is considered an effective legislator, and is sitting on a sizable war chest. But some conservative activists view him with suspicion, given his pragmatic approach to working with Democrats.

Other GOP candidates include grocery store owner Brandon Trosclair, an election denier; deep-pocketed Public Service Commissioner Mike Francis; and former state Rep. Nancy Landry, who has worked in Ardoin’s office for four years (and is not related to Jeff Landry).

The lone Democrat currently in the race is attorney, accountant, and small business owner Gwen Collins-Greenup. She has already run twice for secretary of state, losing to Ardoin both times with 41% of the vote. With that kind of track record, she has a good shot at getting past the primary but losing the runoff.

Kentucky (Republican Michael Adams)

Adams is a Republican who is tolerable to many Democrats. He fruitfully negotiated bipartisan electoral reforms with Beshear, a Democrat, receiving praise from across the ideological spectrum. Despite opposition from his right, Adams won a May primary with a little shy of two-thirds of the vote.

Democratic nominee Buddy Wheatley is from the region of northern Kentucky, which is in the Cincinnati orbit — this part of the state is reliably Republican at the presidential level but portions of it ended up contributing to Beshear’s winning gubernatorial coalition in 2019. Wheatley was a state representative but lost reelection after his district was redrawn to be unfavorable. Wheatley is considered a strong candidate, and he’s been attacking Adams fairly aggressively, but defeating a politician as well-liked as Adams will not be easy.

Utah (Republican Sean Reyes)

Reyes can seek a third full term as attorney general in 2024. No one has emerged as either a primary or general election challenger. Until someone does, Reyes should have smooth sailing. Reyes was mentioned many months ago as a potential primary challenger to Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT), but we have not heard anything about that recently.

Montana (Republican Austin Knudsen)

There’s no indication that Knudsen, who’s in his first term, won’t seek reelection. While Knudsen has irritated some Republicans in the state, he would be a heavy favorite in heavily Republican Montana unless he gets a primary challenge or seeks higher office. No names of potential Democratic challengers have surfaced.

West Virginia: Open seat (Patrick Morrisey, R, is running for governor)

West Virginia’s ascendant GOP has at least two credible candidates for this open-seat contest: state Sen. Ryan Weld, a member of the chamber’s leadership, and fellow state Sen. Mike Stuart, a former state Republican chairman and a former U.S. attorney appointed by then-President Donald Trump. Of the two, Weld is considered more of a pragmatist, while Stuart has positioned himself as more of a populist.

No Democrat has announced a run. Either way, the real action is expected to come in the GOP primary.

Missouri (Republican Andrew Bailey)

When Eric Schmitt left the AG office to become a U.S. senator, GOP Gov. Mike Parson appointed Bailey, his general counsel, to fill the vacancy. Now Bailey is running for a term of his own.

Bailey is continuing Schmitt’s conservative politics and is running with the aid of incumbency. But he won’t have a free ride in the GOP primary. One candidate already in the race is Will Scharf, a former federal prosecutor and onetime aide to then-Gov. Eric Greitens, a Republican who resigned the office amid a personal scandal. Other potential Republican candidates include Tim Garrison, a former U.S. attorney and Marine Corps veteran; state Sen. Tony Luetkemeyer, a cousin once removed from GOP Congressman Blaine Luetkemeyer; and John Wood, a former federal prosecutor and unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate in 2022. Wood dropped out of that race, in which he was running as an independent, after Greitens lost to Schmitt in the 2022 Senate primary.

On the Democratic side is state Rep. Sarah Unsicker and, with an exploratory committee established, Elad Gross, who lost the 2020 Democratic primary for AG. However, Missouri has become so solidly red that Democrats face huge hurdles in winning statewide office.

Indiana (Republican Todd Rokita)

Rokita has been highly visible, and controversial, including for pursuing sanctions against a physician who spoke to the media about the case of a 10-year-old rape victim that attracted national attention.

Still, Rokita should be well-funded and benefit from grassroots support. If Democrats can recruit a credible candidate, they could make this a race, but no names have emerged yet, and there are few Democrats who would make credible statewide candidates in Indiana any more.

North Carolina: Open seat (Josh Stein, D, is running for governor)

Historically, North Carolina has been a competitive state in down-ballot races. Will that enable Democrats to keep their longstanding hold on the AG office as Stein runs for governor? It’s hard to say.

The leading Republican in the race is former state Rep. Tom Murry, though there is talk that GOP Congressman Dan Bishop, who is better known, might get into the contest. On the Democratic side is attorney and veteran Tim Dunn, though if new, GOP-leaning congressional lines are drawn, Democratic Rep. Jeff Jackson could enter the race rather than compete in an unfriendly district.

With the final candidate lineup in limbo, and given the state’s competitive nature down the ballot, we will start this contest as a Toss-up.

Pennsylvania: Open seat (Appointed AG Michelle Henry, D, is not running)

The Democrats have a trio of credible, declared candidates: former Auditor General Eugene DePasquale, former Bucks County Solicitor Joe Khan, and former top Philadelphia public defender Keir Bradford-Grey. Potentially in the wings are several other credible Democratic candidates: former Congressman and Senate candidate Conor Lamb, state Rep. Jared Solomon, and Delaware County District Attorney Jack Stollsteimer.

No Republican is officially in the race yet, but several plausible candidates are considering bids, including former U.S. attorney and gubernatorial candidate Bill McSwain, state Reps. Natalie Mihalek and Craig Williams, former U.S. Attorney Scott Brady, York County District Attorney Dave Sunday, and Westmoreland County District Attorney Nicole Ziccarelli.

Democrats feel good about their chances of holding this seat, which was occupied by Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro until he moved up in 2022. Democrats did well in the Keystone State in the 2022 midterms, and the presidential contest in 2024 should ensure high turnout. But Pennsylvania is a swingy state, with Republicans winning the state auditor general and treasurer races in 2020, and the GOP plans to take this race seriously, so we’ll start it in the Toss-up category. That could change depending on who the nominees are.

Washington state: Open seat (Bob Ferguson, D, is running for governor)

Ferguson leaves big shoes to fill as he runs for governor, but Washington state Democrats have a deep bench. Already in the race is state Sen. Manka Dhingra. Other Democrats who could join her include outgoing U.S. Attorney Nicholas Brown (who just resigned in advance of a run), state Sen. Drew Hansen, and Solicitor General Noah Purcell.

The GOP has a weak bench and, at least for now, shows no signs of competing aggressively for AG’s office.

Oregon (Democrat Ellen Rosenblum)

Rosenblum, who has held the office since 2012, would be a lock for reelection if she runs again, but she could retire. Any jockeying for the seat has taken a back seat to the legislative session in which Republican state senators have been denying the Democratic majority a quorum for months. (The walkout began May 3 and ended June 15.) But Democrats should have little to worry about, regardless of who their nominee is.

Vermont (Democrat Charity Clark)

Clark was elected AG in 2022 and should have no trouble winning a second two-year term in solidly blue Vermont.

Texas

Keep an eye on Texas, where GOP Attorney General Ken Paxton is facing possible removal from office after being impeached by the GOP-controlled state House.

If Paxton is ousted, which would require a 2/3rds majority vote of the state Senate, there would be a special election concurrent with the 2024 presidential election, with a March 2024 primary at the same time as that for other offices. Gov. Greg Abbott (R) would appoint an AG to serve between Paxton’s removal and the election of the new AG in 2024 (Abbott has already appointed an interim AG, John Scott, to take Paxton’s place temporarily while Paxton faces his impeachment trial). The winner would serve out the remainder of Paxton’s current term, which runs through January 2027.

West Virginia: Open seat (Mac Warner, R, is running for governor)

So far, the top GOP contenders for this open seat race include state Del. Chris Pritt, former state Del. Ken Reed, former state Sen. Kenny Mann, and longtime Putnam County Clerk Brian Wood. None of the candidates is considered widely known across the state, but whoever wins the nomination would be heavily favored against the eventual Democratic nominee.

Missouri: Open seat (Jay Ashcroft, R, is running for governor)

On the Republican side, Greene County Clerk and former state Rep. Shane Schoeller, who also was the 2012 GOP nominee for this office, has filed to run, but observers expect the GOP field for this open seat to grow. Whoever wins the nomination would be the heavy favorite against whichever Democrat wins the nomination.

Montana (Republican Christi Jacobsen)

Jacobsen is expected to run for reelection and would be heavily favored. No Democratic names have surfaced, and the bench for Montana Democrats is thin. But Democrats hold out hope of finding a candidate who can surf the expected turnout boost from Sen. Jon Tester’s (D-MT) reelection bid.

North Carolina (Democrat Elaine Marshall)

Despite North Carolina’s slight Republican lean, Marshall has become something of an institution in the state, having first been elected as secretary of state in 1996. But she won her most recent race by only about 2 percentage points in 2020, so the election should be competitive.

The GOP field includes Darren Eustance, a political consultant and the former chair of the Wake County Republican Party, and Gaston County Commissioner Chad Brown. Neither is well known, especially compared to Marshall. Incumbency gives Marshall a slight edge, but the contest should be competitive.

Oregon (Vacant)

Democratic Secretary of State Shemia Fagan resigned in May after a scandal regarding consulting work for a cannabis company. Democratic Gov. Tina Kotek has yet to appoint someone to fill the vacancy, though by law it must be a Democrat. Kotek’s appointed incumbent would be eligible to run in 2024, but it’s unclear whether the governor favors naming a caretaker or giving someone a head start on running for a full term.

Whichever option Kotek pursues, Democrats will be strongly favored to keep the office.

Washington (Democrat Steve Hobbs)

Hobbs, who was appointed to the office in 2021 and won the remainder of an unexpired term in 2022, should have no trouble winning again in 2024.

Vermont (Democrat Sarah Copeland Hanzas)

Copeland Hanzas, who won her first term as secretary of state in 2022, will be heavily favored to win again in 2024.

| Louis Jacobson is a Senior Columnist for Sabato’s Crystal Ball. He is also the senior correspondent at the fact-checking website PolitiFact and is senior author of the forthcoming Almanac of American Politics 2024. He was senior author of the Almanac’s 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 editions and a contributing writer for the 2000 and 2004 editions. |

— The Supreme Court’s Allen v. Milligan decision should give Democrats at least a little help in their quest to re-take the House majority, but much remains uncertain.

— As of now, the Democrats’ best bets to add a seat in 2024 are in Alabama, the subject of the ruling, and Louisiana.

— It also adds to the list of potential mid-decade redistricting changes, which have happened with regularity over the past half-century.

— The closely-contested nature of the House raises the stakes of each state’s map, and redistricting changes do not necessarily have to be prompted by courts.

Landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions can sometimes be categorized as either beginnings or endings. Take, for instance, a couple of past important decisions that at least touch on the topic of redistricting.

In 1962, the court’s Baker v. Carr decision was a beginning: After decades of declining to enter what Justice Felix Frankfurter described as the “political thicket” of redistricting and reapportionment, the Supreme Court opened the door to hearing cases that argued against the malapportionment of voting districts. A couple of years later, the court’s twin decisions of Reynolds v. Sims and Wesberry v. Sanders mandated the principle of “one person, one vote” be used in drawing, respectively, state legislative and congressional districts, kicking off what is known as the “reapportionment revolution.”

More recently, the court’s 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision represented an ending: The court threw out the preclearance coverage formula of the Voting Rights Act. Prior to that decision, certain states and jurisdictions (mostly but not entirely in the South) had to submit changes in voting procedures, such as redistricting plans, to the U.S. Department of Justice for preclearance. The court said that this method of determining which places needed preclearance was outdated, and Congress has never mandated a new preclearance formula. So prior to the Shelby County decision, a state like Alabama would have had to have cleared its new congressional district map with the Justice Department. In 2021, it did not have to.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Allen v. Milligan last week is neither a beginning nor an ending, although Republican authorities in Alabama and others surely hoped it would represent a form of the latter. Rather, the case is best thought of as a continuation of current law and how the Supreme Court interprets current law — namely, that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the so-called “Gingles test” that undergirds it still exists in the same way we understood them prior to the Milligan decision.

The Gingles test is a three-pronged assessment, laid out as followed in the 1986 Supreme Court decision Thornburg v. Gingles (we’re quoting directly from that decision). These are the conditions that need to be in place in order for a federal court to order the creation of a new majority-minority district:

— “First, the minority group must be able to demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district.”

— “Second, the minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive.”

— “Third, the minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it… usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

Basically, the thing that was surprising about Milligan is that Democrats and their allies thought it was going to be bad for their side to at least a certain degree given the conservative makeup of the court. Instead, the Supreme Court didn’t really change anything.

We are not lawyers, and we will not pretend to be lawyers. Racial redistricting jurisprudence is, to us and likely to many others, confusing. Following discussions with some people who follow redistricting matters on both sides of the political aisle, we’re going to try to assess the fallout from the decision. Let’s start in Alabama and work our way to other states. This is not intended to touch on every single state with potential redistricting legal action that may or may not be impacted by Milligan; rather, we just wanted to hit the highlights of certain states and what the state of play in each is:

— In the Milligan case, a District Court found that Alabama’s congressional map likely violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by creating a single district where Black voters made up a majority when it should have created two. Alabama is just over a quarter Black, but Black voters constitute a majority of just one of the state’s seven districts (14%). Those who sued over the map persuasively showed that it’s possible to draw a second Black district that satisfies the conditions of the Gingles test. What the actual map will eventually look like remains a mystery, but the likeliest outcome seems to be that instead of Alabama having a single, overwhelmingly Democratic district (the current 7th District, represented by Democrat Terri Sewell), the state seems likely to eventually have two districts that Democrats are favored to win. This is now reflected in our Crystal Ball House ratings — after the decision last Thursday, we tweeted that we were moving one unspecified Alabama district from Safe Republican to Likely Democratic. We say only Likely Democratic because it’s possible that this new district would not be an absolute slam dunk Democratic victory (or perhaps AL-7 would be reconfigured in such a way that it would be borderline competitive).

— A federal court in Louisiana made an analogous ruling in that state, which is politically similar to Alabama. Louisiana is about a third Black, but only one district (the 2nd, held by Democrat Troy Carter) is majority Black, so the state has five Safe Republican districts and one Safe Democratic district. Again, the endgame here very well could be that Democrats end up getting another seat, but we want to see how things play out. Louisiana uses a unique “jungle primary” system, in which all candidates compete together in the same primary, with a runoff required if no one clears 50%. Does that have an impact on the eventual jurisprudence here, or on how a newly-drawn district might perform politically? Or does Louisiana’s system help Democrats, given that because of the jungle primary — which in 2024 will occur concurrent with the November general election — filing deadlines are late in Louisiana, which gives this case extra time to wind through the legal system in advance of the 2024 election. It may be the case that despite Louisiana being similar to Alabama, the Gingles test may not force a second majority-Black district there in the same way as might happen in Alabama — or that is at least what state Republicans want the U.S. Supreme Court to ponder. (Democrats and their allies of course disagree and see Alabama and Louisiana as very similar — that makes sense to us, too, but we shall see.)

— This case also could force changes in Georgia, although it seems possible that a new map there wouldn’t actually change the partisan balance in the state, which is 9-5 Republican following a GOP gerrymander there in advance of the 2022 election. In other words, perhaps a currently Democratic seat in the Atlanta area could be altered to satisfy a court order to add an extra Black seat without actually giving the Democrats an extra seat. Court-ordered redraws do not always lead to changes to the political bottom line: North Carolina Republicans were ordered to redraw their congressional map because of racial gerrymandering concerns in advance of the 2016 election, but they did so in such a way that they were able to preserve their 10-3 statewide majority (we’ll get back to North Carolina later).

— A federal court also ruled against the South Carolina congressional map earlier this year, but it did so in a different way than in the Alabama case. Unlike in, say, Alabama and Louisiana, it might be difficult to satisfy the Gingles test in South Carolina to add a second Black district because of the compactness prong of Gingles: The Black population share in the state is very similar to Alabama, but Black South Carolinians are just more geographically spread out. So when thinking about Milligan’s ramifications, we aren’t including South Carolina in our calculations, based on our best understanding. The U.S. Supreme Court is slated to hear this case in its next term.

— The situation is also different in Florida, where there is ongoing litigation over the partisan gerrymander successfully pushed by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) last cycle. Among other things, that map undid a Safe Democratic, substantially Black (but not majority Black) district that ran from Jacksonville to Tallahassee. The state Supreme Court in Florida may order that district restored in some form — although the court is fairly aligned with DeSantis, so we wouldn’t necessarily bet on it — but, if it does, the court’s decision would be based on particulars in the state constitution, amended by voters in 2010 to prevent gerrymandering, as opposed to federal law (Democratic analyst Matt Isbell had a good rundown of the situation there if you’re curious).

— Texas also comes up in discussions of the ripple effects of the Milligan ruling, but the situation there is more complicated in part because the discussion is more about Latino voters than Black voters, and Latino voters are not as politically cohesive as Black voters are — which, again, may complicate a court using the Gingles test to force a redraw there.

So what’s the upshot here? Again, and we have to stress this even though it’s an answer that won’t satisfy anyone, we are just going to have to wait to see how things shake out. But we do think some of the post-Milligan analysis that suggested that Democrats could enjoy a windfall of several seats in time for the 2024 election is, at the very least, premature. That may happen, eventually, but at the moment we’re most focused on the likelihood of a single extra Democratic seat in Alabama (which is now reflected in our ratings) and quite possibly Louisiana (which is not reflected in our ratings, at least for now).

One other thing to remember — just because Democrats got a ruling that they liked here does not mean that this very conservative court is going to start ruling for them on related cases in the future. As others noted, the key vote in this 5-4 decision was probably Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who left some breadcrumbs suggesting that Alabama just did not make the right arguments in this case. This is part of the reason why we are not making a ton of assumptions right now about what is next in states beyond Alabama.

Speaking of future Supreme Court decisions, Milligan was not the only important redistricting-related case in front of the court this term: We are still waiting to see what the Supreme Court says in Moore v. Harper.

That case is about the North Carolina state Supreme Court’s intervention against a Republican gerrymander in advance of the 2022 election. That intervention turned what would have been a 10-4 or even 11-3 Republican map in North Carolina into what became a 7-7 tie in November 2022, saving the Democrats several seats. Since then, Republicans have taken control of the North Carolina court, which already overruled its previous decision that defanged Republican gerrymandering efforts. So Moore v. Harper appears very unlikely to have any practical bearing now on North Carolina itself: Republicans are going to have the power to restore a gerrymander there.

The importance of the case from a redistricting perspective, then, is whether the U.S. Supreme Court will impose constraints on state judicial interventions against congressional maps. We have no idea what the court is going to do — it might just punt the decision given that North Carolina’s Supreme Court reversed itself after it changed from Democratic to Republican in 2022. However, the U.S. Supreme Court may issue a decision that impacts the ability of other state courts to intervene against gerrymandering. That could have ripple effects, like in Wisconsin, where the state’s new, Democratic-leaning state Supreme Court may be tempted to rule against Republican partisan gerrymanders later this year. Stay tuned.

Since the Supreme Court’s aforementioned Wesberry v. Sanders decision, which applied the concept of “one person, one vote” to congressional redistricting, there have been 30, two-year congressional election cycles (every even-numbered year from 1964 through 2022). Based on research I did for my history of recent House elections, 2021’s The Long Red Thread, at least one congressional district (and often more) changed from the previous cycle in 23 of those 30 election cycles. Most of these changes (though not all) were forced by courts. The 2024 cycle will make it 24 of 31 cycles, with potentially several states changing their maps in response to court orders. We bring this up to say that despite the now-familiar rhythm of all the states with at least two districts redrawing to reflect the census at the start of every decade, it’s common for at least some districts to change more often than that.

Beyond the states mentioned above, at least some of which will have new maps next year, Ohio is also likely to have a new map that quite possibly will be better for Republicans than the current one, which the Ohio Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional but which was eventually used anyway in 2022 (just like in North Carolina, the Ohio Supreme Court has since changed in such a way to make it more amenable to GOP redistricting prerogatives going forward). Democrats in New York are trying to force a new map, in part because of changes to that state’s highest court that may make that court more amenable to Democratic redistricting arguments than the previous court, which undid a Democratic gerrymander. The particulars in both states require longer-winded explanations that we’ll save for another time.

And aside from the changes forced by courts, one also wonders if we will eventually see a redistricting technique that at one time was common but really has not been in recent decades: a state legislature enacting an elective, mid-decade remap without prompting by the courts.

The most famous modern example of this is when Texas Republicans redrew their state’s congressional map following the 2002 election. That gerrymander, which is most closely associated with former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R), came after Republicans took full control of Texas state government in 2002. They replaced a court-drawn map that reflected a previous Democratic gerrymander and imposed their own partisan gerrymander, turning a 17-15 deficit in what had become a very Republican state into a 21-11 advantage. Georgia Republicans did something similar later in the decade, though to much less effect; Colorado Republicans tried to but were blocked by state courts — some states do not allow mid-decade redistricting, but others do (there is no federal prohibition on mid-decade redistricting). North Carolina’s looming redraw is somewhat similar to those in Texas and Georgia from the 2000s: The voters changed the political circumstances — Republicans taking control of Texas and Georgia state government in 2002 and 2004, respectively, and Republicans flipping the North Carolina Supreme Court in 2022 — paving the way for the partisan gerrymanders that did (or will) follow.

The redistricting stakes are extremely high at a time when U.S. House majorities are so narrow. Democrats won just a 222-213 majority in 2020, and Republicans won the same 222-213 edge last year. It’s possible that the net impact of mid-decade redistricting — including some of the changes we’ve laid out above — could be decisive in who wins the majority next year. It may also prompt other states to try to go back to the redistricting well without prompting by courts — and if they determine they can based on state law — if they believe that new maps could make a difference in determining majorities.

| Dear Readers: We’re pleased to welcome polling expert Natalie Jackson back to the Crystal Ball this week. She explores Donald Trump’s continued strength in the GOP despite a recent indictment. We also urge you to listen to our recent Politics is Everything podcast episode with Natalie, where we discussed Trump, the GOP’s polling requirements for entry into primary debates, and much more. Listen and subscribe here or wherever you get your podcasts.

— The Editors |

— Despite a second indictment, Donald Trump remains in a strong position in the GOP presidential primary field.

— Trump continues to earn majorities or near-majorities in polls, far outpacing his rivals, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

— Republicans would rather have a nominee they agree with than an electable one.

As the Republican presidential primary field fills out and former President Donald Trump confronts a second indictment, an intriguing battle of numbers has emerged among GOP pollsters aligned with Trump and Florida Gov. (and now candidate) Ron DeSantis over whether Trump can win a general election against President Joe Biden.

In a column for National Journal a couple of weeks ago, I discussed the team DeSantis argument and why leaked numbers that are favorable for Trump’s archrival are nothing to hang one’s hat on. The pollsters affiliated with DeSantis (or pro-DeSantis PACs) continue to push back on polls that look strong for Trump. In many cases their critiques are valid, but it’s unclear that a non-Trump Republican would overcome the hurdles they cite as problems for Trump.

Shortly after, team Trump has started pushing back by pointing out that the general electorate knows little about DeSantis, and demonstrating how they can make the DeSantis polling numbers look worse by saying bad things about him. That’s a common campaign message testing strategy that campaign pollsters use to figure out their opponents’ weaknesses — it’s just usually not made public. Like the pro-DeSantis leaked polls, however, this pro-Trump memo was leaked to make a specific point.

That was before Trump’s latest indictment, but the arraignment in Miami looks to change little in the GOP primary race. The particular Trump vs. DeSantis electability data war is likely to continue, as DeSantis has chosen to attack the Justice Department rather than Trump. Trump still maintains three significant advantages that DeSantis and the other candidates will have to climb a mountain to overcome:

It’s still early, but both FiveThirtyEight’s and RealClearPolitics’s polling averages show Trump currently above 50% in national primary polls, and solidly leading in early state polls. Only a few polls have emerged since the indictment, but there is not a clear sign of this changing. It’s still early (repetition intentional), but breaking the 50% threshold is substantial, particularly given that the remaining vote has to be divided among a lot of candidates and only DeSantis regularly gets into double digits. A CBS News-YouGov poll, partially conducted after the latest indictment news, shows 75% of likely Republican voters are considering voting for Trump, with the next contender (DeSantis) being considered by 52% — and from there it drops to a fifth or less. Even if Trump loses a few percentage points due to the indictment, the uphill climb for the challengers is steep with a lot of rock scrambling.

That same CBS News-YouGov poll shows that 62% of Republicans say Trump would definitely beat Biden in 2024. A recent Monmouth University Poll had a similar finding — that 63% of Republican voters think Trump is likely their best bet. These numbers could certainly change. That’s true of any numbers in this column — that’s why I keep saying it’s still early. But nearly two-thirds of the potential primary electorate thinks Trump is the one to beat Biden. That means most Republicans are not open to DeSantis’s argument that he’s more electable. If people aren’t open to an argument, it won’t be very effective.

A moderate Republican would have a smoother pathway to victory than Trump or DeSantis, particularly given Biden’s lackluster numbers, age, and relatively low-key persona. But moderate candidates face a very difficult primary environment where ideologues are more likely to vote for strong conservatives. A March CNN poll showed 59% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents would choose a candidate they agree with on the issues over a candidate who has a strong chance to beat Biden (41%). This undoubtedly favors Trump over other candidates. Michael Tesler pointed out in FiveThirtyEight that Republicans now equate Trump support with conservatism. The CBS News-YouGov poll showed that Republicans split 50-50 on whether they should focus on appealing to moderates and independents vs. motivating conservatives and Republicans.

There are still two significant complicating factors for Trump, though. The first is obviously his ongoing legal risk, with now two indictments and additional investigations ongoing. However, these investigations don’t seem to affect Republicans’ views of him, although an ABC News-Ipsos poll conducted after the second indictment does show that 38% of Republicans think the charges are serious, compared to only 21% in the first indictment. That said, the same poll shows that 80% of Republicans think the new charges are politically motivated, and nothing prevents Trump from running while under indictment — or even from prison.

The other complication is that the GOP primary field is large. It remains possible that one of these alternatives could catch on with voters and dislodge some of Trump’s supporters. A large field challenging an ex-president (an incumbent once-removed?) seems odd if Trump is really the party leader.

Contrast that with 2020, when Trump faced no significant challenges. That said, the GOP would have to align behind one alternative by January or so in order to give that candidate any chance of winning the nomination. And even then, we have no idea whether Trump or DeSantis, or any other candidate, would win. You can say it the other way, too: We have no idea whether Biden will win. It’s too early and the numbers all show a close race, as I wrote a couple of weeks ago.

Still, the evidence we have now indicates that if the field remains Trump vs. nearly a dozen (or more) others, Utah Sen. Mitt Romney is correct: Trump is “by far” the most likely Republican presidential nominee in 2024. Electable or not.

| Natalie Jackson is a research consultant working in political polling and a contributing editor with National Journal. More of her writing can be found on her substack. |

— The percentage of women in state legislatures has increased in recent years. However, there is still a significant gender gap in most states as women have not reached parity in representation.

— The majority of women in state legislatures are Democrats. While more Republican women ran for office in 2022 than in previous years, that didn’t amount to closing the gender gap in representation.

— The percentage of women in state legislatures has increased more in Western and Northeastern states than in Midwestern and Southern states. This is likely due to a number of factors, including the political climate, the level of motivation and activism among women, and the availability of resources for women’s campaigns.

In a special election on May 16, Democrats maintained a narrow majority in the Pennsylvania House of Delegates. As a result, the party will be able to continue to exert control over how the lower chamber of the state legislature will handle reproductive, gun, and voting rights legislation. With Republicans still holding the Pennsylvania Senate, the House could also provide an assist to Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro in budget negotiations. In House District 163, Democratic candidate Heather Boyd defeated Republican candidate Katie Ford for a vacancy created by Democratic Rep. Mike Zabel, who resigned from the legislature after multiple people, including a lobbyist and other lawmakers accused him of sexual harassment. That two women vied for the House seat is a sign of change for a state legislature that has been accused in the past by other women lawmakers of having a paternalistic culture and being an “Old Boys Club.”

But it’s not just Pennsylvania that’s changing. In early April, as the Tennessee House was about to vote on expulsion resolutions for Reps. Justin Pearson (D-Memphis), Justin Jones (D-Nashville), and Gloria Johnson (D-Knoxville) for leading a protest against gun violence on the House floor on March 30, Johnson told her colleagues in the state legislature that they should welcome a new generation of lawmakers who are going to look and do things differently because they “are fighting like hell” for their constituents. Meanwhile, in Nebraska, a bill that would ban abortion around the 6th week of pregnancy failed to get a crucial 33rd vote to break a filibuster in the technically nonpartisan and unicameral state legislature when Republican Sen. Merv Riepe abstained. When Riepe got pushback on an amendment he introduced to extend the proposed ban from 6 to 12 weeks, he told his Republican colleagues that reproductive rights will have women voting them out of office. He offered as evidence his own narrowing margins of victory against a Democratic woman challenger in a post-Dobbs election as a preview of what’s to come. In South Carolina, where women make up only 11% of the upper chamber, the opposition of all five women, including three Republicans, led to the failure of a near-total abortion ban by a 22-21 vote in April. While a comparatively less strict fetal heartbeat ban did eventually pass in May with the continued opposition of the five women, that they were able to prevent the passage of a stricter bill is another example of how women in decision-making positions can impact policy outcomes.

These vignettes got me thinking about how representation in state legislatures is (or is not) changing and prompted us to do a series examining trends. In this first installment, I examine how women’s representation has changed in American state legislatures since 1975. To analyze change in women’s representation in state legislatures from 1975 to 2023, I compiled data from several sources, including the National Conference of State Legislatures, Ballotpedia, and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) at the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University. Political science scholarship has shown that descriptive representation matters. Specifically, scholarship on gender and politics has shown that men and women have different policy preferences, and that female legislators are more likely to emphasize women’s issues and adopt women-friendly policies (see a good review of the literature here).

According to CAWP, the number of women serving in state legislatures has more than quintupled since 1971. Figure 1 shows the change in the percentage of women legislators in lower legislative chambers of all 50 states between 1975 and 2023. Readers can hover over each state to see pop-ups with additional information for each state, including a breakdown of women legislators by party each year. Note: Nebraska has a unicameral legislature, but I include it in both upper and lower chamber figures for comparison.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of women legislators in upper legislative chambers of all 50 states between 1975 and 2023. Readers can hover over each state to see pop-ups with additional information for each state, including a breakdown of women legislators by party each year (again, unicameral Nebraska is included on both figures).

Although it didn’t receive much national news media attention, women scored big in the 2022 elections for state legislative seats. As of this year, almost one-third of state legislators are women, and there is a record number of women serving in state legislatures. Maps 1 and 2 below are shaded by the percentage of women’s representation in upper and lower chambers for each state as of 2023. As Map 1 shows, Nevada has the highest percentage of women serving (61.9%) in lower legislative chambers, while Mississippi has the lowest (11%). Map 2 shows that Nevada also has the highest percentage of women in upper chambers (61.9%), while South Carolina has the lowest (10.9%).

While the increase in representation is a positive sign, there is still a significant gender gap in most states. Women have reached parity in representation in just 3 lower state legislative chambers (Colorado, New Mexico, and Nevada) and in just 3 upper chambers (Arizona, New Hampshire, and Nevada). Compare that to the fact that women make up about 50.7% of the population nationally, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Women also have higher reported voter registration and voting rates than men for every federal election since 1984, according to data from the Current Population Survey.

As of 2022, the most recent year for which race and ethnicity data is available, the majority of women legislators are white (73.2%). Women of color make up 24.6% of women legislators, with Black women comprising 16.1%, Latinas 6.7%, Middle Eastern .5%, and Native American/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian 1.3%.

Maps 1 and 2 contain pop-up information with additional details by state, including the percentage point change from 2010 to 2023 of women serving in upper and lower chambers. The change in the percentage of women in lower legislative chambers since 2010 ranges from a decrease of 9 percentage points in West Virginia to an increase of 31 percentage points in Nevada. The top 10 states with the greatest percentage point increase in women’s representation in lower legislative chambers are Nevada (+30.9 percentage points), Oregon (+21.6), New Mexico (+21.4), Rhode Island (+20), Colorado (+19.9), Delaware (+19.5), Virginia (+19), Washington (+18.4), Florida (+17.5), and Kentucky (+17). Lower legislative chambers in 6 states experienced no growth or decline: Wyoming (0 pp increase), Kansas (-2.4), North Carolina (-4.2), Mississippi (-4.9), Tennessee (-6.1) and West Virginia (-9), all of which are controlled by Republicans.

Not surprisingly, it has been more challenging for women to break barriers in upper legislative chambers than lower chambers. While women’s representation has increased in 40 of 50 states since 2010, there are still states with relatively low percentages of women serving in the upper chamber. Women have 20% or less of representation in 10 states, all controlled by Republicans: South Carolina (10.9%), Alabama (11.4%), West Virginia (11.8%), Louisiana (12.8%), Arkansas (14.2%), North Dakota (17%), Indiana (18%), Mississippi (19.2%), Utah (20.7%), and Oklahoma (20.8%). And our home base of Virginia, which will have legislative elections later this year, is just barely ahead, with 22.5% of women in the Democratic-controlled state Senate.

There are 10 states that experienced an increase of 15 percentage points or more in women’s representation in upper legislative chambers since 2010: Nevada (+28.6 percentage points), Rhode Island (+23.6), North Carolina (+20), Illinois (+18.7), Florida (+17.5), Wyoming (+16.6), Nebraska (unicameral, +16.3), Michigan (+15.8), New York (+15.7), and California (+15). Upper legislative chambers in 10 states experienced no growth or decline since 2010: Delaware (0 percentage point increase), Hawaii (0), Massachusetts (0), Tennessee (0), Arkansas (-2.9), Colorado (-3), Oregon (-3.3), New Hampshire (-4.1), Alabama (-5.6), Minnesota (-7.5), Indiana (-12), and Louisiana (-12.8).

The variation in the percentage of women in state legislatures and change can be attributed to a variety of factors, including the political climate, the level of motivation and activism among women, and the availability of resources for women to run and serve in office.

Since Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election and as issues affecting women’s rights to self-determination have been at the forefront in the last couple election cycles, there has been a renewed interest for women to run for office and serve in politics. In general, there have been more efforts to recruit and train Democratic candidates to run for office. However, the Republican Party is doing a better job of recruiting women than in the past. In 2022, the Republican State Leadership Committee reported that 769 Republican women and minority candidates were elected to state legislative positions, an increase over 2020. The RSLC also said that it spent $5.3 million recruiting, training, and supporting diverse candidates. While more Republican women ran for office in 2022 than in previous years, that didn’t amount to closing the gender gap in representation, especially in Republican-controlled legislatures in the South. As of 2023, one-third of all women state legislators are Republican, and Republican women account for 10.9% of all state legislators.

Overall, the increase in women elected to state legislatures has particularly come from the Democratic Party, with 1,580 Democratic women lawmakers serving in upper and lower state legislative chambers. Two-thirds of all women legislators are Democrats, and Democratic women account for 21.4% of all state legislators. The biggest increase for Democratic women legislators occurred in the 2018 election cycle — we’ll call that the Trump effect.

In addition to the political parties, there are organizations and PACs at the national and state levels focused on recruiting and supporting women. I reviewed a database of organizations that CAWP maintains and found that the majority of the organizations are nonpartisan (65.7%), while 20.5% of them are Democratic-affiliated and 13.8% are Republican-affiliated. Organizations with a national focus make up 15.3% of the total, and the remaining are state-focused (including state-based chapters of national organizations). California (6.2% of all organizations) and Texas (4.2%) stand out with the greatest percentage of state-based organizations. Still, not all women who go through political leadership programs run for office. And the percentage of organizations in a state doesn’t translate to parity.

Good politics and policy depend on diverse perspectives and lived experiences, but women remain underrepresented at all levels of government. As this analysis shows, the number of women in state legislatures is increasing, and this is a positive trend. However, as this analysis also demonstrates, progress is not a given and there are clearly states where more attention to closing the gender gap in representation is needed.

For women to achieve parity in representation, there are structural challenges that states can address, including for example, by increasing salaries for legislators and providing stipends for childcare. There are also ways in which political parties and organizations can address the challenges women and other minoritized candidates face by expanding recruitment, encouragement, and training efforts, while increasing financial support for women to run for office. Openings and incumbency are also issues, and may require encouraging more women to challenge candidates from their own parties in primaries.

| Dear Readers: Join us on Tuesday, April 11 for a conversation with Nguyen Quoc Dzung, ambassador of Vietnam to the United States. The ambassador will speak on the relationship between Vietnam and the U.S. and issues impacting Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

The program begins at 6:30 p.m. eastern at Minor Hall, Room 125, on the Grounds of the University of Virginia. It is free and open to the public to attend with advanced registration through Eventbrite; it will also be livestreamed at https://livestream.com/tavco/ambassadorofvietnam. — The Editors |

— After looking at the Midwest last week, we’re comparing the presidential voting trajectory of the bigger counties versus the rest of the state in a number of eastern states.

— Georgia had exactly opposite top and bottom halves in 2020, with a very Republican (but stable) bottom half and Democratic-trending top half driven by changes in Atlanta.

— North Carolina and Pennsylvania are mirror images on opposite sides of the political divide.

— Florida’s turn toward the Republicans has been a bit more pronounced in its top half of bigger counties compared to its bottom half, making it an outlier among the states we’ve studied.

— South Carolina’s status as a red state is much more about its top half than its bottom half.

James Brown’s version of the song “Night Train” — one of the best songs ever recorded, in my humble opinion — calls out the path of a train starting from Miami and moving up the eastern seaboard. Among other places, the train stops in Atlanta, Raleigh, Richmond, and Philadelphia.

What does this have to do with presidential politics? Well… nothing really. It’s just that I heard the song over the weekend as I was trying to tie together the collection of eastern states I’m analyzing this week. This is a follow-up to last week’s exploration of how the biggest counties in a state vote for president compared to the rest of the state. So, I thought, the Night Train’s path kind of does the trick. Plus, if this apparent non sequitur inspires you to listen to the song, well, trust me, your day will be better off for it.

After analyzing 7 Midwestern states last week, we turn east this week, looking at a series of states extending from Pennsylvania in the north to Florida in the South. They are geographically connected, except that we skipped Maryland on account of it being so overwhelmingly Democratic.

These are a politically diverse group of states, including red South Carolina, bluish Virginia, reddening Florida, and 3 of the nation’s premier battlegrounds: Georgia, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania.

Just like last week, we split each state in half, grouping together the biggest-voting counties that added up to roughly half the statewide vote in the 2020 presidential election (the top half) and comparing them to the other counties that make up the rest of the state (the bottom half). We used Dave Leip’s Atlas of Presidential Elections for the results, and Dave’s Redistricting App to highlight the top half counties in orange on the maps that follow. For a more detailed explanation of methodology, see last week’s piece.

All aboard?

Top half counties that add up to half the statewide vote: Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach in South Florida cast about a quarter of the statewide vote. Others in this group are Hillsborough and Pinellas, which make up the core of the Tampa/St. Petersburg/Clearwater area; Duval (Jacksonville) in the northeast; Orange (Orlando) in central Florida; and Lee (Fort Myers/Cape Coral in the southwest). Joe Biden won all of these but Lee; Barack Obama won 6 of the 8, losing Duval and Lee.

Bottom half counties that make up the other half of the statewide vote: The state’s other 59 counties; Obama lost all but 7, Biden lost all but 5.

Of the 13 Midwestern/eastern states we’ve looked at as part of this analysis, Florida has an unusual distinction: It is the only 1 of the 13 where the Democrats’ margin in the top half dropped more than their margin in the bottom half from 2012 to 2020. As you can see in Table 1, the drop was similar — 4.4 points in margin in the top half and 3.9 in the bottom half — which makes it an outlier, too, as generally (not always) the bottom halves of these states have gotten substantially more Republican as the top halves have seen only a modest Democratic decline or, sometimes, a small or even large pro-Democratic shift.

A big reason for a Republican shift in the big counties is that the 3 big South Florida counties were considerably less blue in 2020 than they were in 2012: Obama won the trio by 26 points, while Biden won them by 16 points. Miami-Dade has driven that shift, going from a 24-point Obama margin (and 29 for Hillary Clinton in 2016) to just 7 for Biden in 2020, but the other 2 got less blue as well, albeit not as dramatically.

Overall, Florida has a bottom half that is comparable to some states in the Midwest, perhaps in part because Florida’s booming retirement communities (many of which have big populations but are included in the bottom half) have many Midwestern expats (we looked at some of these counties last year). Trump won Florida’s bottom half of counties by 18 points, very similar to Wisconsin (15 points) and Minnesota (17 points). But the top half of Florida only voted for Biden by 11 points, comparable to the top half of Iowa (12 points), a state that like Florida has shifted right recently. Florida is definitely more competitive than the double-digit victories by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) and Sen. Marco Rubio (R) last year, but it’s also clearly trending toward Republicans.

Top half: 11 counties, with 9 of those being part of the Greater Atlanta area (Fulton, Gwinnett, Cobb, DeKalb, Cherokee, Forsyth, Henry, Clayton, and Hall, in order of most to least populous). The other 2 counties outside of Atlanta’s orbit are Chatham (Savannah) in the southeast and Richmond (Augusta) in the east. Biden won 8 of these 11, with the exceptions being Atlanta exurbs Cherokee, Forsyth, and Hall. Obama won just 5 of the 11: Clayton, DeKalb, and Fulton in the Atlanta area in addition to Chatham and Richmond.

Bottom half: Georgia has a lot of counties, and 148 of the 159 make up the bottom half. Obama won 29 of these counties, while Biden won 22. Like many other Southern states, Georgia has a lot of rural and heavily Black Democratic counties, which helps account for Democrats’ ability to win these counties, although as their dwindling number suggests, many of these counties have still drifted towards Republicans.

The change in Georgia has been essentially entirely driven by its top half counties, which is dominated by counties in the Atlanta orbit. The Democratic presidential margin in Georgia’s top half has swelled from 10 points in 2012 to 26 points in 2020. Meanwhile, the bottom half has hardly changed at all, moving from a 25-point Republican margin to a 26-point margin. In Georgia, Republicans were effectively already maxed out with rural white voters prior to Trump, and there also are a substantial number of votes in the bottom half from majority Black rural counties and a few larger Democratic-leaning counties to keep Democrats from getting completely blown out in that group (the bottom halves of Iowa and Ohio, for instance, are redder now than the bottom half of Georgia). The bottom and the top halves gave their respective candidates 25.7-point margins — exactly the same, down to a tenth of a point. Biden won because the top half counties cast slightly more of the vote, based on this calculation (50.5% vs. 49.5% for the bottom half).

The bottom line is if Republicans can’t stop the bleeding in the Greater Atlanta area, Georgia eventually could go the way of Virginia and become bluer than the nation as opposed to redder (which it still is).

Top half: The dozen counties that make up North Carolina’s top half are generally centered around Raleigh-Durham, Charlotte, and the Piedmont Triad (Greensboro/High Point/Winston-Salem). The biggest source of votes is Wake (Raleigh), and neighboring Durham and Johnston counties are also in this group. Mecklenburg (Charlotte), the second-largest source of votes, is also included, along with neighboring Union, Cabarrus, and Gaston. Guilford (Greensboro) and Forsyth (Winston-Salem) cast the third and fourth-most votes, respectively, and are located west of the Raleigh-Durham metro area. Finally, Buncombe (Asheville), Cumberland (Fayetteville), and New Hanover (Wilmington) provide other vote anchors in, respectively, the western, south-central, and southeastern parts of the state. Biden won 8 of these 12 counties, losing only the suburban/exurban Johnston south of Raleigh as well as the suburban/exurban satellites of Mecklenburg: Cabarrus, Gaston, and Union. Obama won 7 of the 12, with the same lineup as Biden except Obama narrowly lost New Hanover while Biden won it.

Bottom half: The other 88 counties: Obama won 23, Biden won 17.

The Tar Heel State is in a period of considerable flux, with the gap between its top and bottom halves expanding. But for all of the positive Democratic trends in the top half, the bottom half has gotten considerably more Republican over the same time period, too, keeping the state persistently right of center.

At the topline level, North Carolina voted very similarly in 2012 and 2020, producing a 2-point margin for Mitt Romney and then a 1.3-point margin for Donald Trump. In each election, the state was the Republican nominee’s closest victory. Yet like other states, that statewide similarity masks a lot of changes happening at the sub-state level, with Democrats getting bigger margins in the major urban areas but losing ground elsewhere. Biden was the first postwar Democratic nominee to clear 60% of the vote in both Mecklenburg and Wake counties and still came up short, speaking to how much the rest of the state has moved. Two key places of Democratic slippage have come in the northeast, home to several heavily Black rural counties where Democratic performance is not as strong as it once was, as well as a mix of counties near the South Carolina border between Charlotte and Fayetteville. Robeson County, home of the Lumbee Indian tribe, is a prime example, as it went from 58%-41% Obama to 59%-41% Trump in just 8 years.