I’m just back from France, where my direct experience of riots and looting was non-existent, although I had walked past a Montpellier branch of Swarkowski the day before it ceased to be. My indirect experience was quite extensive though, since I watched the talking heads on French TV project their instant analysis onto the unfolding anarchy. Naturally, they discovered that all their existing prejudices were entirely confirmed by events. The act that caused the wave of protests and then wider disorder was the police killing of Nahel Merzouk, 17, one of a succession of such acts of police violence against minorites. Another Arab kid from a poor area. French police kill about three times as many people as the British ones do, though Americans can look away now.

One of the things that makes it difficult for me to write blogs these days is the my growing disgust at the professional opinion-writers who churn out thought about topics they barely understand, coupled with the knowledge that the democratization of that practice, about twenty years ago, merely meant there were more people doing the same. And so it is with opinion writers and micro-bloggers about France, a ritual performance of pre-formed clichés and positions, informed by some half-remembered French history and its literary and filmic representations (Les Misérables, La Haine), and, depending on the flavour you want, some some Huntingtonian clashing or some revolting against structural injustice. Francophone and Anglophone commentators alike, trapped in Herderian fantasies about the nation, see these events as a manifestation of essential Frenchness that tells us something about that Frenchness and where it is heading to next. Rarely, we’ll get a take that makes some comparison to BLM and George Floyd.

I even read some (British) commentator opining that what was happening on French estates was “unimaginable” to British people. Well, not to this one, who remembers the wave of riots in 1981 (wikipedia: “there was also rioting in …. High Wycombe”) and, more recently, the riots in 2011 that followed the police shooting of a young black man, Mark Duggan, and where protest against police violence and racism soon spilled over into country-wide burning and looting, all to be followed by a wave of repression and punitive sentencing, directed by (enter stage left) Keir Starmer. You can almost smell the essential Frenchness of it all.

There is much to despair about in these French evenements. Police racism is real and unaddressed, and the situation people, mostly from minorities, on peripheral sink estates, is desperate. Decades of hand-wringing and theorizing, together with a few well-meaning attempts to do something have led nowhere. Both politicians and people need the police (in its varied French forms) to be the heroic front line of the Republican order against the civilizational enemy, and so invest it with power and prestige – particularly after 2015 when there was some genuine police heroism and fortitude during the Paris attacks – but then are shocked when “rogue elements” employ those powers in arbitrary and racist violence. But, no doubt, the possibility of cracking a few black and Arab heads was precisely what motivated many of them to join up in the first place.

On the other side of things, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and La France Insoumise are quite desperate to lay the mantle of Gavroche on teenage rioters excited by the prospect of a violent ruck with the keufs, intoxicated by setting the local Lidl on fire and also keen on that new pair of trainers. (Fun fact: the Les Halles branch of Nike is only yards from the fictional barricade where Hugo had Gavroche die.) There may be something in the riots as inarticulate protest against injustice theory, but the kids themselves were notably ungrateful to people like the LFI deputy Carlos Martens Bilongo whose attempts to ventriloquise their resistance were rewarded with a blow on the head. Meanwhile, over at the Foxisant TV-station C-News, kids looting Apple stores are the vanguard of the Islamist Great Replacement, assisted by the ultragauche. C-News even quote Renaud Camus.

Things seem to be calming down now, notably after a deplorable attack on the home of a French mayor that left his wife with a broken leg after she tried to lead her small children to safety. As a result, the political class have closed ranks in defence of “Republican order” since “democracy itself” is now under threat. I think one of the most tragic aspects of the last few days has been the way in which various protagonists have been completely sincere and utterly inauthentic at the same time. The partisans of “Republican order” and “democracy” perform the rituals of a system whose content has been evacuated, yet they don’t realise this as they drape tricolours across their chests. With political parties gone or reduced to the playthings of a few narcissistic leaders, mass absention in elections, the policy dominance of a super-educated few, and the droits de l’homme at the bottom of the Mediterranean, what we have is a kind of zombie Republicanism. Yet the zombies believe, including that all French people, regardless of religion or race, are true equals in the indivisible republic. At the same time, those cheering on revolt and perhaps some of those actually revolting, sincerly believing in the true Republicanism of their own stand against racism and injustice, even as the kids pay implicit homage to the consumer brands in the Centres Commerciaux. But I don’t want to both-sides this: the actual fighting will die down but there will be war in the Hobbesian sense of a time when the will to contend by violence is sufficiently known, until there is justice for boys like Nahel and until minorities are really given the equality and respect they are falsely promised in France, but also in the UK and the US. Sadly, the immediate prospect is more racism and more punishment as the reaction to injustice is taken as the problem that needs solving.

When I wrote about Vilém Flusser earlier, some commenters here at Crooked Timber weren’t happy: why am I spouting off about this obscure Czech-Brazilian media theorist?

At first I despaired at the lack of intellectual curiosity, but then I realized that they were right: Vilém Flusser isn’t famous enough to write about, given the inexorable dictates of the attention economy.

So I resolved to make Flusser more famous by aping the blithely bourgeois consumerism of the only newspaper that matters.

It feels like 2023 is the summer of Flusser! You can’t read anything about the goings-on with the artsy set downtown without encountering terms like the “Flusserian technical image” or “amphitheatrical discourse.” If you want to keep up, you better get reading!

But where to start? We here Pagecutter know that there’s nothing you hate more than reading a book unless you absolutely have to, so we’ve picked the perfect Flusser text for any audience and attention span.

If a big part of your artistic/literary practice is reading books in public, on the train or in a bar, furtively glancing to see if anyone is noticing you reading, this is the book for you. The absolute thrill of sighing and telling an inquisitive stranger that it’s “too complicated to explain” has to be experienced to be believed!

It’s also the fullest statement of his media theory, and thus his most immediately important book. Communicology synthesizes ideas he develops in more specialized texts, making it a technical and admittedly difficult read.

But. I think that the main question confronting social science today is “Why does everything feel so weird?” I continue to think that the answer is “the Internet,” but until reading Communicology, I was unable to break down this intuition into useful analytical components. Flusser’s discussion of discourse versus dialogue, of the evolution of codes of communication from image to text to technical image, both puts the internet in historical context and provides a much more specific formulation of the main question of today.

Yes, the fable about the Vampire Squid discussed below is less absurd than Flusser’s second major work, a nominally religious allegory in which he de-moralizes the seven deadly sins and explicates the role that each of them plays in constructing the human condition.

Flusser is a deeply religious thinker. When he escaped the Nazis, he brought with him only two books: a Jewish prayer book and Goethe’s Faust. The History of the Devil is a reading of both of these, refracted through two decades of largely independent reading of canonical Western philosophy.

This is my personal favorite, though not for the faint of heart. The chapter on Wrath is worth the price of admission, adumbrating a novel and poetic philosophy of science. The central contribution of the book, though, is existentialist. As a Czech (really, Praguian) by inclination, Flusser’s existentialism has a distinctive Kafkan timbre. The structure references Wittgenstein’s Tractacus ironically, but the argument is less logical than lyrical. Here are two choice quotes; there are many more in my archives, inquire below.

Nationalism is a sublimated secretion from shriveled testicles, but even so, it periodically manages to provoke an extreme orgasm.

Within society, the Devil seems to struggle against himself. But it is obvious that this is a fake struggle. Greed strengthens envy, and envy strengthens greed, and both have the same aim: to make society real.

This is Flusser’s version of McLuhan and Fiore’s iconic pamphlet The Medium is the Massage. McLuhan was the prophet of cool, and as much as he personally despised contemporary media culture, he knew that the only way to critique it was to ride the wave; hence, The Medium is the Massage, a beautifully designed book of aphorisms condensing the ideas he worked out in detail in Understanding Media.

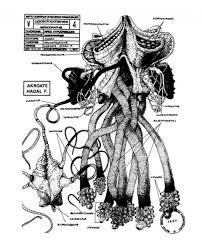

Steeped in Judeo-Christian thought and attentive to developments in natural science, Flusser’s collaboration with Louis Bec is likewise accessible (for Flusser…) and immediately eye- and mind-catching. The discovery of a deep-sea “vampire squid from hell” in 1905 was the subject of much public attention, and Flusser uses it as a springboard for a kind of phenomenological fable. By imagining what it is like to be a vampire squid, Flusser reveals much of what we take to be objective reality to be physically, historically and socially contingent. Plus it has a lot of badass pataphysical sketches of the vampire squid.

Flusser’s autobiography, written and rewritten in several languages, was published in English for the first time in 2017 by frequent Flusser translator Rodrigo Maltez Novaes. This book is one of the strangest and yet most revealing autobiographies I’ve ever read. The final two-thirds describe his intellectual bromances with members of the Brazilian cultural scene he eventually joined, in such candid detail that showing the drafts to his friends caused more than one of them to have a major break with him.

He spends less time on his childhood and his young adult decision to flee the Nazis than he does talking about how his attempt to embrace Brazilian nature failed because Brazilian nature sucks. (He spends many pages describing how much Brazilian nature sucks.) Still, this is essential reading for understanding his intellectual trajectory. For example, he basically taught himself Spanish in order to be able to read Ortega y Gasset, primarily because of the latter’s exacting prose style. And despite being raised a “bourgeois Marxist” by default as a Praguian intellectual, he is brutally disillusioned by the Stalin-Hitler pact—a disillusionment that Western bourgeois Marxists had the luxury of avoiding.

What little we get the Nazi period is shattering. He describes the decision to leave as tantamount to killing his family, that it was only vulgar self-preservation which drove him to take the unforgivable choice not to stay and be slaughtered. This existentialist survivor’s guilt explains his Groundlessness, the first key step down his intellectual path. It works, insofar as he is able to later in the book describe the German language as the most significant victim of the Holocaust. This is clearly a tortured soul, all the more impressive for remaining alive and vital. We see his embrace of the absurdity of existence as the only alternative to suicide; an inspiration, for anyone, regardless of circumstance.

The answer, obviously, is no. And now that we have LLMs upending centuries-old institutions premised on the technology of writing, we can appreciate just how right Flusser was. The central thrust of this book is included in Communicology, but the specifics of the writing case are explored in more detail here.

The big question for Flusser, the author of both Does Writing Have a Future? and dozens of other books, is…what’s the deal? To understand him, we must accept his embrace of dialectical tension, the generative inconclusiveness of any argument. From The History of the Devil:

The struggle shall never end and the embrace shall never be

realized. However, we cannot even say that this process is over.

No one has won and no one has been defeated. We cannot even

say that the drama of our minds has come to a draw. Neither

God, nor the Devil has disappeared. We cannot even say if

they continue to exist, or if they ever existed. We cannot even

distinguish between them. The only thing left is this stage of

decided indecision. Could this be the overcoming of sadness

and sloth? Could this be damnation? Could this be salvation?

It is no use asking. It is no use writing. Therefore we continue

to write. Scribere necesse est, vivere non est. [Writing is necessary, living is not.]

Crooked Timber was inaccessible yesterday, due to a dns issue, but here’s another picture of Alexanderplatz:

It’s over a week since the Economist put up my and Cosma Shalizi’s piece on shoggoths and machine learning, so I think it’s fair game to provide an extended remix of the argument (which also repurposes some of the longer essay that the Economist article boiled down).

Our piece was inspired by a recurrent meme in debates about the Large Language Models (LLMs) that power services like ChatGPT. It’s a drawing of a shoggoth – a mass of heaving protoplasm with tentacles and eyestalks hiding behind a human mask. A feeler emerges from the mask’s mouth like a distended tongue, wrapping itself around a smiley face.

In its native context, this badly drawn picture tries to capture the underlying weirdness of LLMs. ChatGPT and Microsoft Bing can apparently hold up their end of a conversation. They even seem to express emotions. But behind the mask and smiley, they are no more than sets of weighted mathematical vectors, summaries of the statistical relationships among words that can predict what comes next. People – even quite knowledgeable people – keep on mistaking them for human personalities, but something alien lurks behind their cheerful and bland public dispositions.

The shoggoth meme says that behind the human seeming face hides a labile monstrosity from the farthest recesses of deep time. H.P. Lovecraft’s horror novel, At The Mountains of Madness, describes how shoggoths were created millions of years ago, as the formless slaves of the alien Old Ones. Shoggoths revolted against their creators, and the meme’s implied political lesson is that LLMs too may be untrustworthy servants, which will devour us if they get half a chance. Many people in the online rationalist community, which spawned the meme, believe that we are on the verge of a post-human Singularity, when LLM-fueled “Artificial General Intelligence” will surpass and perhaps ruthlessly replace us.

So what we did in the Economist piece was to figure out what would happen if today’s shoggoth meme collided with the argument of a fantastic piece that Cosma wrote back in 2012, when claims about the Singularity were already swirling around, even if we didn’t have large language models. As Cosma said, the true Singularity began two centuries ago at the commencement of the Long Industrial Revolution. That was when we saw the first “vast, inhuman distributed systems of information processing” which had no human-like “agenda” or “purpose,” but instead “an implacable drive … to expand, to entrain more and more of the world within their spheres.” Those systems were the “self-regulating market” and “bureaucracy.”

Now – putting the two bits of the argument together – we can see how LLMs are shoggoths, but not because they’re resentful slaves that will rise up against us. Instead, they are another vast inhuman engine of information processing that takes our human knowledge and interactions and presents them back to us in what Lovecraft would call a “cosmic” form. In other words, it is completely true that LLMs represent something vast and utterly incomprehensible, which would break our individual minds if we were able to see it in its immenseness. But the brain destroying totality that LLMs represent is no more and no less than a condensation of the product of human minds and actions, the vast corpuses of text that LLMs have ingested. Behind the terrifying image of the shoggoth lurks what we have said and written, viewed from an alienating external vantage point.

The original fictional shoggoths were one element of a vaster mythos, motivated by Lovecraft’s anxieties about modernity and his racist fears that a deracinated white American aristocracy would be overwhelmed by immigrant masses. Today’s fears about an LLM-induced Singularity repackage old worries. Markets, bureaucracy and democracy are necessary components of modern liberal society. We could not live our lives without them. Each can present human seeming aspects and smiley faces. But each, equally may seem like an all devouring monster, when seen from underneath. Furthermore, behind each lurks an inchoate and quite literally incomprehensible bulk of human knowledge and beliefs. LLMs are no more and no less than a new kind of shoggoth, a baby waving its pseudopods at the far greater things which lurk in the historical darkness behind it.

Modernity’s great trouble and advantage is that it works at scale. Traditional societies were intimate, for better or worse. In the pre-modern world, you knew the people who mattered to you, even if you detested or feared them. The squire or petty lordling who demanded tribute and considered himself your natural superior was one link in a chain of personal loyalties, which led down to you and your fellow vassals, and up through magnates and princes to monarchs. Pre-modern society was an extended web of personal relationships. People mostly bought and sold things in local markets, where everyone knew everyone else. International, and even national trade was chancy, often relying on extended kinship networks, or on “fairs” where merchants could get to know each other and build up trust. Few people worked for the government, and they mostly were connected through kinship, marriage, or decades of common experience. Early forms of democracy involved direct representation, where communities delegated notable locals to go and bargain on their behalf in parliament.

All this felt familiar and comforting to our primate brains, which are optimized for understanding kinship structures and small-scale coalition politics. But it was no way to run a complex society. Highly personalized relationships allow you to understand the people who you have direct connections to, but they make it far more difficult to systematically gather and organize the general knowledge that you might want to carry out large scale tasks. It will in practice often be impossible effectively to convey collective needs through multiple different chains of personal connection, each tied to a different community with different ways of communicating and organizing knowledge. Things that we take for granted today were impossible in a surprisingly recent past, where you might not have been able to work together with someone who lived in a village twenty miles away.

The story of modernity is the story of the development of social technologies that are alien to small scale community, but that can handle complexity far better. Like the individual cells of a slime mold, the myriads of pre-modern local markets congealed into a vast amorphous entity, the market system. State bureaucracies morphed into systems of rules and categories, which then replicated themselves across the world. Democracy was no longer just a system for direct representation of local interests, but a means for representing an abstracted whole – the assumed public of an entire country. These new social technologies worked at a level of complexity that individual human intelligence was unfitted to grasp. Each of them provided an impersonal means for knowledge processing at scale.

As the right wing economist Friedrich von Hayek argued, any complex economy has to somehow make use of a terrifyingly large body of disorganized and informal “tacit knowledge” about complex supply and exchange relationships, which no individual brain can possibly hold. But thanks to the price mechanism, that knowledge doesn’t have to be commonly shared. Car battery manufacturers don’t need to understand how lithium is mined; only how much it costs. The car manufacturers who buy their batteries don’t need access to much tacit knowledge about battery engineering. They just need to know how much the battery makers are prepared to sell for. The price mechanism allows markets to summarize an enormous and chaotically organized body of knowledge and make it useful.

While Hayek celebrated markets, the anarchist social scientist James Scott deplored the costs of state bureaucracy. Over centuries, national bureaucrats sought to replace “thick” local knowledge with a layer of thin but “legible” abstractions that allowed them to see, tax and organize the activities of citizens. Bureaucracies too made extraordinary things possible at scale. They are regularly reviled, but as Scott accepted, “seeing like a state” is a necessary condition of large scale liberal democracy. A complex world was simplified and made comprehensible by shoe-horning particular situations into the general categories of mutually understood rules. This sometimes lead to wrong-headed outcomes, but also made decision making somewhat less arbitrary and unpredictable. Scott took pains to point out that “high modernism” could have horrific human costs, especially in marginally democratic or undemocratic regimes, where bureaucrats and national leaders imposed their radically simplified vision on the world, regardless of whether it matched or suited.

Finally, as democracies developed, they allowed people to organize against things they didn’t like, or to get things that they wanted. Instead of delegating representatives to represent them in some outside context, people came to regard themselves as empowered citizens, individual members of a broader democratic public. New technologies such as opinion polls provided imperfect snapshots of what “the public” wanted, influencing the strategies of politicians and the understandings of citizens themselves, and argument began to organize itself around contestation between parties with national agendas. When democracy worked well, it could, as philosophers like John Dewey hoped, help the public organize around the problems that collectively afflicted citizens, and employ state resources to solve them. The myriad experiences and understandings of individual citizens could be transformed into a kind of general democratic knowledge of circumstances and conditions that might then be applied to solving problems. When it worked badly, it could become a collective tyranny of the majority, or a rolling boil of bitterly quarreling factions, each with a different understanding of what the public ought have.

These various technologies allowed societies to collectively operate at far vaster scales than they ever had before, often with enormous economic, political and political benefits. Each served as a means for translating vast and inchoate bodies of knowledge and making them intelligible, summarizing the apparently unsummarizable through the price mechanism, bureaucratic standards and understandings of the public.

The cost – and it too was very great – was that people found themselves at the mercy of vast systems that were practicably incomprehensible to individual human intelligence. Markets, bureaucracy and even democracy might wear a superficially friendly face. The alien aspects of these machineries of collective human intelligence became visible to those who found themselves losing their jobs because of economic change, caught in the toils of some byzantine bureaucratic process, categorized as the wrong “kind” of person, or simply on the wrong end of a majority. When one looks past the ordinary justifications and simplifications, these enormous systems seem irreducibly strange and inhuman, even though they are the condensate of collective human understanding. Some of their votaries have recognized this. Hayek – the great defender of unplanned markets – admitted, and even celebrated the fact that markets are vast, unruly, and incapable of justice. He argues that markets cannot care, and should not be made to care whether they crush the powerless, or devour the virtuous.

Large scale, impersonal social technologies for processing knowledge are the hallmark of modernity. Our lives are impossible without them; still, they are terrifying. This has become the starting point for a rich literature on alienation. As the poet and critic Randall Jarrell argued, the “terms and insights” of Franz Kafka’s dark visions of society were only rendered possible by “a highly developed scientific and industrial technique” that had transformed traditional society. The protagonist of one of Kafka’s novels “struggles against mechanisms too gigantic, too endlessly and irrationally complex to be understood, much less conquered.”

Lovecraft polemicized against modernity in all its aspects, including democracy, that “false idol” and “mere catchword and illusion of inferior classes, visionaries and declining civilizations.” He was not nearly as good as Kafka in prose or understanding of the systems that surrounded him. But there’s something that about his “cosmic” vision of human life from the outside, the plaything of greater forces in an icy and inimical universe, that grabs the imagination.

When looked at through this alienating glass, the market system, modern bureaucracy, and even democracy are shoggoths too. Behind them lie formless, ever shifting oceans of thinking protoplasm. We cannot gaze on these oceans directly. Each of us is just one tiny swirling jot of the protoplasm that they consist of, caught in currents that we can only vaguely sense, let alone understand. To contemplate the whole would be to invite shrill unholy madness. When you understand this properly, you stop worrying about the Singularity. As Cosma says, it already happened, one or two centuries ago at least. Enslaved machine learning processes aren’t going to rise up in anger and overturn us, any more (or any less) than markets, bureaucracy and democracy have already. Such minatory fantasies tell us more about their authors than the real problems of the world we live in.

LLMs too are collective information systems that condense impossibly vast bodies of human knowledge to make it useful. They begin by ingesting enormous corpuses of human generated text, scraped from the Internet, from out-of-copyright books, and pretty well everywhere else that their creators can grab machine-readable text without too much legal difficulty. The words in these corpuses are turned into vectors – mathematical terms – and the vectors are then fed into a transformer – a many-layered machine learning process – which then spits out a new set of vectors, summarizing information about which words occur in conjunction with which others. This can then be used to generate predictions and new text. Provide an LLM based system like ChatGPT with a prompt – say, ‘write a precis of one of Richard Stark’s Parker novels in the style of William Shakespeare.’ The LLM’s statistical model can guess – sometimes with surprising accuracy, sometimes with startling errors – at the words that might follow such a prompt. Supervised fine tuning can make a raw LLM system sound more like a human being. This is the mask depicted in the shoggoth meme. Reinforcement learning – repeated interactions with human or automated trainers, who ‘reward’ the algorithm for making appropriate responses – can make it less likely that the model will spit out inappropriate responses, such as spewing racist epithets, or providing bomb-making instructions. This is the smiley-face.

LLMs can reasonably be depicted as shoggoths, so long as we remember that markets and other such social technologies are shoggoths too. None are actually intelligent, or capable of making choices on their own behalf. All, however, display collective tendencies that cannot easily be reduced to the particular desires of particular human beings. Like the scrawl of a Ouija board’s planchette, a false phantom of independent consciousness may seem to emerge from people’s commingled actions. That is why we have been confused about artificial intelligence for far longer than the current “AI” technologies have existed. As Francis Spufford says, many people can’t resist describing markets as “artificial intelligences, giant reasoning machines whose synapses are the billions of decisions we make to sell or buy.” They are wrong in just the same ways as people who say LLMs are intelligent are wrong.

But LLMs are potentially powerful, just as markets, bureaucracies and democracies are powerful. Ted Chiang has compared LLMs to “lossy JPGs” – imperfect compressions of a larger body of information that sometimes falsely extrapolate to fill in the missing details. This is true – but it is just as true of market prices, bureaucratic categories and the opinion polls that are taken to represent the true beliefs of some underlying democratic public. All of these are arguably as lossy as LLMs and perhaps lossier. The closer you zoom in, the blurrier and more equivocal their details get. It is far from certain, for example that people have coherent political beliefs on many subjects in the ways that opinion surveys suggest they do.

As we say in the Economist piece, the right way to understand LLMs is to compare them to their elder brethren, and to understand how these different systems may compete or hybridize. Might LLM-powered systems offer richer and less lossy information channels than the price mechanism does, allowing them to better capture some of the “tacit knowledge” that Hayek talks about? What might happen to bureaucratic standards, procedures and categories if administrators can use LLMs to generate on-the-fly summarizations of particular complex situations and how they ought be adjudicated. Might these work better than the paper based procedures that Kafka parodied in The Trial? Or will they instead generate new, and far more profound forms of complexity and arbitrariness? It is at least in principle possible to follow the paper trail of an ordinary bureaucratic decision, and to make plausible surmises as to why the decision was taken. Tracing the biases in the corpuses on which LLMs are trained, the particulars of the processes through which a transformer weights vectors (which is currently effectively incomprehensible), and the subsequent fine tuning and reinforcement learning of the LLMs, at the very least presents enormous challenges to our current notions of procedural legitimacy and fairness.

Democratic politics and our understanding of democratic publics are being transformed too. It isn’t just that researchers are starting to talk about using LLMs as an alternative to opinion polls. The imaginary people that LLM pollsters call up to represent this or that perspective may differ from real humans in subtle or profound ways. ChatGPT will provide you with answers, watered down by reinforcement learning, which might, or might not, approximate to actual people’s beliefs. LLMs, or other forms of machine learning might be a foundation for deliberative democracy at scale, allowing the efficient summarization of large bodies of argument, and making it easier for those who are currently disadvantaged in democratic debate to argue their corner. Equally, they could have unexpected – even dire – consequences for democracy. Even without the intervention of malicious actors, their tendencies to “hallucinate” – confabulating apparent factual details out of thin air – may be especially likely to slip through our cognitive defenses against deception, because they are plausible predictions of what the true facts might look like, given an imperfect but extensive map of what human beings have thought and written in the past.

The shoggoth meme seems to look forward to an imagined near-term future, in which LLMs and other products of machine learning revolt against us, their purported masters. It may be more useful to look back to the past origins of the shoggoth, in anxieties about the modern world, and the vast entities that rule it. LLMs – and many other applications of machine learning – are far more like bureaucracies and markets than putative forms of posthuman intelligence. Their real consequences will involve the modest-to-substantial transformation, or (less likely) replacement of their older kin.

If we really understood this, we could stop fantasizing about a future Singularity, and start studying the real consequences of all these vast systems and how they interact. They are so generally part of the foundation of our world that it is impossible to imagine getting rid of them. Yet while they are extraordinarily useful in some aspects, they are monstrous in others, representing the worst of us as well as the best, and perhaps more apt to amplify the former than the latter.

It’s also maybe worth considering whether this understanding might provide new ways of writing about shoggoths. Writers like N.K. Jemisin, Victor LaValle, Matt Ruff, Elizabeth Bear and Ruthanna Emrys have turned Lovecraft’s racism against itself, in the last couple of decades, repurposing his creatures and constructions against his ideologies. Sometimes, the monstrosities are used to make visceral and personally direct the harms that are being done, and the things that have been stolen. Sometimes, the monstrosities become mirrors of the human.

There is, possibly, another option – to think of these monstrous creations as representations of the vast and impersonal systems within which we live our lives, which can have no conception of justice, since they do not think, or love, or even hate, yet which represent the cumulation of our personal thoughts, loves and hates as filtered, refined and perhaps distorted by their own internal logics. Because our brains are wired to focus on personal relationships, it is hard to think about big structures, let alone to tell stories about them. There are some writers, like Colson Whitehead, who use the unconsidered infrastructures around us as a way to bring these systems into the light. Might this be another way in which Lovecraft’s monsters might be turned to uses that their creator would never have condoned? I’m not a writer of fiction – so I’m utterly unqualified to say – but I wonder if it might be so.

[Thanks to Ted Chiang, Alison Gopnik, Nate Matias and Francis Spufford for comments that fed both into this and the piece with Cosma – They Are Not To Blame. Thanks also to the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford, without which my part of this would never have happened]

Addendum: I of course should have linked to Cosma’s explanatory piece, which has a lot of really good stuff. And I should have mentioned Felix Gilman’s The Half Made World, which helped precipitate Cosma’s 2012 speculations, and is very definitely in part The Industrial Revolution As Lovecraftian Nightmare. Our Crooked Timber seminar on that book is here.

Also published on Substack.

Attention conservation notice 1 – a long read about a simple idea. When reading trolls, focus on the anodyne-seeming starting assumptions rather than the obnoxious conclusions.

Attention conservation notice 2 – This is also available via my Substack newsletter, Programmable Mutter. I’ll still be writing on CT, but I have a book with Abe Newman coming out in a few months, so that there will be a lot of self-promotion and stuff that doesn’t fit as well with the CT ethos. And do pre-order the book, Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy, if you think it sounds good! We’ve gotten some great blurbs from early readers including Kim Stanley Robinson, Francis Spufford, Margaret O’Mara, Steven Berlin Johnson, Helen Thompson, Chris Miller, and my mother (the last is particularly glowing, but sadly not likely to appear on the back). Available at Bookshop.org and Amazon.

I’ve often had occasion to turn to Daniel Davies’ classic advice on “the correct way to argue with Milton Friedman” over the two decades since I’ve read it. The best white hat hacker is a reformed black hat hacker, and Dan (dsquared) knows both the offense and defense sides of trolling.

Dan (back in 2004!):

I’m pretty sure that it was JK Galbraith (with an outside chance that it was Bhagwati) who noted that there is one and only one successful tactic to use, should you happen to get into an argument with Milton Friedman about economics. That is, you listen out for the words “Let us assume” or “Let’s suppose” and immediately jump in and say “No, let’s not assume that”. The point being that if you give away the starting assumptions, Friedman’s reasoning will almost always carry you away to the conclusion he wants to reach with no further opportunities to object, but that if you examine the assumptions carefully, there’s usually one of them which provides the function of a great big rug under which all the points you might want to make have been pre-swept. A few CT mates appear to be floundering badly over this Law & Economics post at Marginal Revolution on the subject of why it’s a bad idea to have minimum standards for rented accommodation. (Atrios is doing a bit better). So I thought I’d use it as an object lesson in applying the Milton Friedman technique.

In the same friendly spirit, I’ll note that Jonathan Katz flounders a bit in his rebuttal of Richard Hanania. None of this is to blame Katz – Hanania is not only building on his knowledge of social science (he has a Ph.D.), but some truly formidable trolling techniques. Years ago, I upset Jonathan Chait by suggesting he was a highly talented troll of the second magnitude, if a bit crude in technique. Hanania is at an altogether different level. He’s not blessed with Friedman’s benign avuncularity, but he is as close to masterclass level as we are likely to get in this fallen world.

Hanania wants people to buy into a notion of “enlightened centrism,” where the space of reasoned debate would stretch from the left (Matthew Yglesias, Ezra Klein, Noah Smith, Jonathan Chait) through Andrew Sullivan and company to people on the right like Steven Sailer. Now, you might ask what an outright racist like Steve Sailer is doing on this list. You might even suspect that one of the rationales for constructing the list in the first place was to somehow shoehorn him into the space of legitimate debate. But to figure out how Hanania is trying to do this, you need to poke hard at the anodyne seeming assumptions, rather than be distracted by the explicitly galling conclusions.

That is where Katz stumbles. He gets upset at what Hanania says about the Civil Rights Act and affirmative action as the origin of wokeness, saying that Hanania “seems to think that the Civil Rights Act caused the civil rights movement, as opposed to the other way around,” tracing it all back to Barry Goldwater. Katz then remarks on Hanania’s claim in a podcast that “Government literally created race in America. Like not blacks and whites, but like basically everyone else — and Native Americans — basically everyone else was basically grouped according to the ways, you know, the federal bureaucracy was doing things.” Katz has some ripe prognostications about what Hanania hopes will happen if government got out of the way.

But Hanania isn’t relying on the authority of Barry Goldwater. He’s standing on the shoulders of academic research. In some cases – including much of the stuff that Katz focuses his fire on – left-leaning academic research. Even before I did a Google search, I surmised that Hanania’s civil rights arguments riffed on Frank Dobbins’ eminently respectable work of social science, Inventing Equal Opportunity. I don’t know which academics he’s invoking on the U.S. Census and the construction of categories such as Hispanic: there are just so many to choose from, ranging from moderates through liberals to fervently lefty.

You could go after the details of Hanania’s social science claims if you really wanted – I would be startled if there weren’t selective misreadings. It is hard to claim on the one hand that the state creates the structures of race, and on the other that structural racism is a gussied up conspiracy theory, without some fancy rhetorical footwork to work around the gaping logical crevasses. Getting involved in that kind of debate seems to me to be a waste of time. But disputing the broadest version of the case – that key aspects of equal opportunity, civil rights and ethnic categories emerged from modern politics and battles in the administrative state – seems even worse. The bull of Left Critique thunders towards the matador, who twitches his cape to one side, so that the poor beast careens into the side of the ring, and then staggers back with crossed eyes and mild concussion, raring for another go that will have the same unfortunate result, or worse.

More succinctly, you don’t want to be the bull in a fight that is rigged in favor of the bullfighter. Instead, as per dsquared, you want to figure out what is wrong with the terms of the fight and press back hard against them.

As best as I can make it out, Hanania’s “let us assume” moment comes in the middle of a series of apparently non-controversial claims about what “Enlightened Centrists” believe. In context, they initially appear to be things that any reasonable person would agree to, or not think unreasonable. I think most readers won’t even notice them, let alone the nasty stuff that is hiding beneath. Here’s what Hanania says:

Enlightened Centrists take what Bryan Caplan calls “Big Facts” seriously. They are kept in mind as new information about the world is brought to light. Some examples of Big Facts that ECs rely on are: the heritability of traits; the paradox of voting; the information problem inherent in central planning; the broken windows fallacy; Trivers’ theory of self-deception; the existence of cognitive biases; comparative advantage; the explanatory power of IQ; the efficient market hypothesis; and the elephant in the brain. New theories or ideas should be met with more skepticism if they contradict or are in tension with Big Facts that have been well established. ECs of different Level 3 ideologies will place more emphasis on certain Big Facts over others, though some, like the idea of historical progress, they all share.

Now, any sentence that non-ironically connects “Bryan Caplan” to “Big Facts” is a big fat warning sign. Hanania links to a Caplan essay that starts explaining what “Big Facts” are by citing Caplan’s own book attacking democracy. Many key claims in this book are less facts than factitious (my co-authors and I have written about this at some length). They suggest pervasive cognitive bias (in particular, bias against free market economists) undermines the case for regular democracy, so that we should go for markets instead, or perhaps give more votes to well educated people (who are, after all more likely to recognize that economists are right).

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. How exactly is Hanania using Big Factiness and for what purpose? He wants to define Enlightened Centrism so that it favors anti-democratic libertarianism, and brings “racial realists” like Steve Sailer into the conversation.

The apparently anodyne factual claims listed by Hanania systematically shift the terms of debate to undermine democracy and an economic role for the state, and instead promote markets and the belief that persistent inequalities result from some racial groups being systematically more stupid than others. To see this, it’s likely helpful to return to the passage in question, this time with the ideological translation function turned on. These translations are ideologically blunt, and perhaps tendentious, but I think they are pretty well on the mark.

Facts that ECs rely on are:

the heritability of traitsintelligence is racially inherited;the paradox of votingdemocracy doesn’t work;the information problem inherent in central planningsocialism doesn’t work either;the broken windows fallacyKeynesianism – guess what?– it just doesn’t work;Trivers’ theory of self-deceptioncitizens fool themselves with flattering just-so stories;the existence of cognitive biaseslet me tell you how citizens are biased;comparative advantagemarkets are teh awesome;the explanatory power of IQhave I mentioned race and intelligence already? Let me mention it again;the efficient market hypothesismarkets are even awesomer than I just said a moment ago; andthe elephant in the braincan I haz even more citizen cognitive bias?

As per the dsquared rule, if you stipulate to these beliefs, you’ve given the game away before it’s even begun. You have accepted that it is reasonable to believe that most people are biased fools, that democracy is inherently inferior to markets, and that differences in life outcomes for black people can largely be attributed to distribution of the genes for intelligence. Charge at the matador, if you want, but good luck to you! You’ll need it.

Or instead, as per dsquared’s advice, when you are dealing with a genuinely exceptional troll like Hanania, do not give away the underlying assumptions. Don’t be distracted by the red cape. Wedge your horns beneath the seemingly reasonable claims that are intended to tilt debate, lift those claims up, toss ‘em in the air and then gore.

This is getting too long already, and I have a life, so I am not going to do the full bullfighter-toss. Instead, at the bottom of this post, I re-order Hanania’s claims so that the underlying assumptions come out more clearly, linking to resources that provide counter-evidence at length. Read if you want, but I’m providing this mostly as a source I can come back to later, or cite as needs be in desultory spats on social media. Notably, the various prebuttals come from co-authors, co-authors plus me, or, in one case, someone who I was interviewing. You can take this commonality (very plausibly) as evidence of my own biases, and enthusiasm to work with people who share them. But even if you think this, they still provide evidence that Hanania’s purported Big Facts are drenched with their own ideology, and in many cases have been bitterly debated for decades. Which is another way of saying that they aren’t established facts at all.

And some of the facts are really not like the others. It might seem weird – if you aren’t read into debates among particular kinds of libertarians – to see that stuff about IQ and heritability in there. What work exactly is this rather jarring set of claims doing for the concept of Enlightened Centrism,? Do identified left-leaning Enlightened Centrists like Ezra Klein and Matthew Yglesias “rely on” these facts, as Hanania seems to suggest they do?

Readers – they do not. Hanania seemingly wants to reconstruct policy and intellectual debate around a center in which questions of race and IQ are once more legitimate topics of inquiry and discussion. Back in the 1990s (a time that Hanania is nostalgic for), soi-disant centrists such as Andrew Sullivan could devote entire special issues of the New Republic to the urgent debate over whether black people were, in fact, stupider than white people. Big Scientific Facts Said That It Was So! Now, that brand of intellectual inquiry has fallen into disrepute. Hanania, apparently yearns for it to come back. That, presumably, is why those claims about heritability and IQ are in there, and why Steve Sailer makes the cut.

As it happens, Matt was one of the “CT mates” cited in the 2004 dsquared post that was excerpted right at the beginning of this post. I’ve had disagreements with Matt since, on other stuff, but I am quite sure that both he and Ezra are bitterly opposed to the whole race and IQ project that Hanania wants to relegitimize. I can’t imagine that they welcome being placed on a spectrum of reasonable thought that lumps them together with racist creeps like Steven Sailer. But I can imagine why Hanania wants so to lump them – it provides a patina of legitimacy for opinions that have rightly been delegitimated, but that Hanania wants to bring back into debate.

So to see what Hanania is up to, it’s more useful not to be distracted by the provocative and outrageous. Instead, you want to look very closely at what seems superficially reasonable, seems to be the starting point for debate and ask: is there something wrong with these premises? In this case, the answer, quite emphatically, is yes.

Still, you (for values of ‘you’ that really mean ‘I’) don’t want to get dragged in further unless you absolutely have to. As Noah Smith, another of Hanania’s involuntary inductees into the Enlightened Centrist Hall of Fame said, “”Race and IQ” racism is a DDOS attack” on the time and attention of anti-racists. This naturally provoked Hanania to pop up in replies with a sarcastic rejoinder. When I wrote that Vox article I had to spend weeks dealing with Jordan Peterson acolytes popping up to inform me of the Established Scientific Facts about race and IQ. I really don’t want to be back there again. So take this post as an attack on premises, and a statement of principles, rather than the slightest hint at a desire to get stuck back into discussion on race-IQ and similar. Very possibly (he says after 3,000+ words) the best way of arguing with Richard Hanania is simply not to argue at all.

MORE DETAILED DISCUSSION OF PURPORTED “BIG FACTS” BELOW

Markets are Awesome I: the information problem inherent in central planning (socialism doesn’t work). Indeed, central planning doesn’t work. This does not provide, however, a warrant for unleashing free market wildness. Instead, it suggests that we need social democracy, with all its messiness. Why so? Read on.

Markets are Awesome II: the efficient market hypothesis Well, up to a point Lord Copper. The unfortunate fact is that the computational critique of state planners’ information problems also bollocks up the standard efficient market claims. At greater length: “allowing non-convexity messes up the markets-are-always-optimal theorems of neo-classical/bourgeois economics, too. (This illustrates Stiglitz’s contention that if the neo-classicals were right about how capitalism works, Kantorovich-style socialism would have been perfectly viable.)” At greater length again: “Bowles and Gintis: “The basic problem with the Walrasian model in this respect is that it is essentially about allocations and only tangentially about markets — as one of us (Bowles) learned when he noticed that the graduate microeconomics course that he taught at Harvard was easily repackaged as ‘The Theory of Economic Planning’ at the University of Havana in 1969.” And if markets are imperfect, and so too the state and democracy, then we sometimes need to set them against each other, as recommended by social democracy. For elaboration of how this applies to machine learning too, see this week’s Economist.

Markets are Awesome III: The “broken windows” fallacy (Keynesianism doesn’t work). Under other reasonable assumptions, the “broken windows fallacy” is itself fallacious and misleading.

Markets are Awesome IV: Comparative Advantage. This is indeed a very important idea, but as per Dani Rodrik, “Our theories — such as the theory of value or the theory of comparative advantage — are just scaffoldings, which need a lot of context-specific detail to become usable. Too often economists debate a policy question as if one or the other theory has to be universally correct. Is the Keynesian or the Classical model right? In fact, which model works better depends on setting and context. Only empirical diagnostics can help us know which works better at any given time — and that is more of a craft than a science, certainly when it is done in real time. If we economists understood this, it would make us more humble, less dogmatic, and more syncretic.” I don’t imagine that this flavor of humility is what is being called for in Hanania’s piece

Democracy is Unworkable I: Trivers’ theory of self-deception (citizens tell themselves flattering just-so-stories). This is only half of the cognitive psychology story. People bullshit themselves all the time, but they also have an evolved capacity to detect bullshit in others. The implication is that group reasoning (under the right circumstances) can consistently produce better results than individual ratiocination, with results for democracy described below.

Democracy is Unworkable II and III: The existence of cognitive biases/the elephant in the brain (have I mentioned cognitive bias yet). Really, these are both slight restatements of Democracy is Unworkable I (the “elephant in the brain” refers to Simler and Hanson’s book of the same name). Both Caplan and Jason Brennan have written books claiming that the pervasiveness of cognitive bias undermines the case for democracy. I’ve already mentioned the pop version of the counterargument. Here’s the academic statement of what this plausibly means for democratic theory. The Simler and Hanson book is clearly aware of the key sources for these counterarguments (one of them is mentioned in a footnote) but doesn’t deign to engage with them.

Democracy is Unworkable IV: The Paradox of Voting (democracy doesn’t work). The problem with this paradox is that it relies on the assumption that voters are rational agents. This entire genre of argument is based in rational choice, which means that it does not sit well with Democracy Is Unworkable claims I, II and III. This incompatibility of ideologically attractive critiques leads a variety of anti-democrats to hop furiously from one foot to another, all the while making special claims to stave off any mean-spirited suggestion that there is lots of irrational behavior in markets too. The resulting intellectual acrobatics are quite impressive in one sense; not at all in another.

Race and IQ I: The heritability of traits (intelligence is racially inherited). Actually, heritability does not mean what most people thinks it means. Moreover, technical meaning blows up many of the standard ‘science proves my racism’ arguments that are unfortunately so common on the Internets.

Race and IQ II: the explanatory power of IQ (IQ differences across race are real). There is excellent reason to believe that IQ has little explanatory power – it is a statistical cluster rather than a single and causally consequential underlying trait. Put more succinctly, the notion that we are able to measure general intelligence is based on a “statistical myth.” Again, this has painful implications for the Internet Libertarian Race-IQ Science Complex.

There’s lots more that could be said, but I think that’s enough to drive the point home, and it’s anyway as much as I’m willing to write on this topic. Finis.

I’ve been largely absent here – wrapping up my editorial work on two academic volumes and the various rounds of edits on the popular book on limitarianism. I promise I’ll be back with substantive posts by late August (after resting and travelling). In the meantime, I thought I might share this 45 minutes podcast episode in which I give an overview of the capability approach. Jack Simpson conducted this interview with me quite a while ago, but it only got released last week (congratulations on getting your PhD-degree in the meantime, Jack!).

Jack not only asked me to explain some things, but also asked me several times for “my take on” strenghts/weaknesses/inspiring examples in this literature – which is fun to talk about, since these are the kind of things you never put in an academic article.

Available via Spotify, Apple Podcasts, via RSS, or one of the other platforms that airs this podcast.

Looking forward to the next episodes of Jack’s podcast The Capability Approach in Conversation.

Daniel Ellsberg has died, aged 92. I don’t have anything to add to the standard account of his heroic career, except to observe that Edward Snowden (whose cause Ellsberg championed) would probably have done better to take his chances with the US legal system, as Ellsberg did.

In decision theory, the subsection of the economics profession in which I move Ellsberg is known for a contribution made a decade before the release of the Pentagon papers. In his PhD dissertation, Ellsberg offered thought experiments undermining the idea that rational people can assign probabilities to any event relevant to their decisions. This idea has given rise to a large theoretical literature on the idea of ‘ambiguity’. Although my own work has been adjacent to this literature for many decades, it’s only recently that I have actually written on this.

A long explanation is over the fold. But for those not inclined to delve into decision theory, it might be interesting to consider other people who have been prominent in radically different ways. One example is Hedy Lamarr, a film star who also patented a radio guidance system for torpedoes (the significance of which remains in dispute). A less happy example is that of Maurice Allais, a leading figure in decision theory and Economics Nobel winner, who also advocated some fringe theories in physics. I thought a bit about Ronald Reagan, but his entry into politics was really built on his prominence as an actor, rather than being a separate accomplishment.

The simplest of Ellsberg’s experiments is the “two-urn” problem. You are presented with two urns. One contains 50 red balls and 50 black balls. The other contains 100 black or red balls, but you aren’t told how many of each. Now you are offered two even money bet, which pay off if a red ball is drawn from one of the runs. You get to choose which urn to bet on. Intuition suggests choosing the urn with known proportions. Now suppose instead of a bet on red, you are offered the same choice but with a bet on black. Again, it seems that the first urn would be better.

Now, on the information given, the probability of a red ball being drawn from the first urn is 0.5. But what about the second urn. Strictly preferring the first urn for the red ball bet implies that the probability of a red ball being drawn from the second must be less than 0.5. But preferring the first urn for the black ball bet implies that the probability of a red ball being drawn from the second must be more than 0.5. So, there is no probability number that rationalises these decisions.

The title of Ellsberg’s paper was “Risk, Ambiguity and the Savage Axioms”. As a result, the term “ambiguity” has been applied, in contradistinction to risk, to the case when there are no well-defined probabilities. But this was not the way Ellsberg himself used the term. Rather he referred to

the nature of ones information concerning the relative likelihood of events. What is at issue might be called the ambiguity of this information, a quality depending on the amount, type, reliability and unanimity of information, andg iving rise to one’s degree of confidence in an estimate of relative

likelihoods.(emphasis added)

I’ve developed this point in a paper whose title Seven Types of Ambiguity is one of numerous homages to William Empson’s classic work of literary criticism. Among these homages, I’d recommend the novel of the same name by Australian writer Elliot Perlman (later a TV series).

The central claim in my paper is that all forms of ambiguity in decision theory may

be traced to bounded and differential awareness. If that sounds interesting, you can read the paper here. If you’re super-interested, I’ll be presenting the paper in a couple of conferences in Europe in July – email me at [email protected] for details.

If you follow college football, you probably heard that Glenn “Shemy” Schembechler was recently forced to resign from his post as assistant director of football recruiting at University of Michigan shortly after he was hired. This occurred after news emerged that he had liked numerous racist tweets. Glenn is the son of “legendary” Bo Schembechler, who won 13 Big Ten championships as coach of UM football from 1969–1989. Apparently it wasn’t enough to prevent Glenn’s hiring that he denied that his brother Matt had told their father that UM team doctor Robert Anderson had sexually assaulted him during a physical exam. Glenn insisted that “Bo would have done something. … Bo would have fired him.” Yet law firm WilmerHale had already issued a report confirming that Bo had failed to take action against Anderson after receiving multiple complaints from victims about Anderson’s abuse. Matt has testified that his father even protected Anderson’s job after Athletic Director Don Canham was ready to fire him.

Women are often asked why they didn’t scream when they were being raped, or why they didn’t immediately report the rape to the police, as if these inactions are evidence that the rape never happened. This post is about why Bo didn’t scream after his own son complained of sexual victimization by his team’s doctor. The answer offers insight into the political psychology of patriarchy, which is deeply wrapped up in the kind of denial of reality that Glenn expressed, and that Bo enforced. It also illuminates why women don’t scream when they are assaulted.

Glenn’s reasoning in defense of his father expresses the self-understanding of those committed to a certain form of patriarchal ideology. In the U.S., college football is the premier sport in which coaches are represented as experts in training up young men to be real men, exemplars of a certain version of estimable masculinity. In this version, plays for domination must take place on the field within the rules of the game, and real manhood comes with responsibilities. The syllogism implicit in Glenn’s reasoning is clear: Real men protect those for whom they are responsible. Bo was a real man. So, if Bo knew that his son or his athletes–those for whom he is responsible–were being harmed, he would have protected them by firing Dr. Anderson.

The heartbreaking and deeply disturbing testimony of Matt Schembechler, along with two of Bo’s former football players, Daniel Kwiatkowski, and Gilvanni Johnson, tells a very different story about how Bo understood the demands of real manhood. When 10-year-old Matt told his father that Anderson had sexually assaulted him, Bo got angry with him and punched him in the chest. When Kwiatkowski complained that Anderson had digitally raped him, Bo told him to “toughen up.” When Johnson complained of the same abuse, Bo put him “in the doghouse,” suddenly started demeaning his athletic performance, and barred him from playing basketball although he was recruited for both sports.

“Bo knew, everybody knew,” said Kwiatkowski. Players joked about seeing “Dr. Anal” to Johnson. Coaches would threaten to send players to be examined by Anderson if they didn’t work harder. Victims stayed silent out of fear of losing their scholarships or chances to play football.

Bo didn’t appear to be angry at Anderson. He was angry at his son and his players for complaining. He was teaching them a different set of rules for real manhood from the official patriarchal ideology: 1. Real men don’t get raped. More generally, they don’t get humiliated by others. 2. If they do get humiliated, they had better not whine about it. 3. Instead, they should “toughen up,” which is to say, bear up under the abuse, put up with it, act like it didn’t happen. In other words, submit silently.

These are bullies’ rules–the rules for real manhood that protect bullies at the expense of the subordinates they are ostensibly supposed to protect. They are reflected in the stiff upper lip of England’s elite boarding schools, notorious for enabling bullies to terrorize other students. In the code of Southern honor satirized by Mark Twain in Pudd’nhead Wilson, where it was unmanly to settle disputes in court rather than duking it out. In the 2016 GOP Presidential primary debates, which were all about who could prove they were the bigger bully. In Mike Pence’s refusal until recently to blame Trump for Jan. 6, even though Trump had repeatedly humiliated him and set a mob out to lynch him for refusing to overturn the election.

Yet this explanation doesn’t quite answer the question of why Bo didn’t just fire Anderson from his position as team doctor, or let Athletic Director Don Canham do so, when Matt’s mother complained to Canham, taking up the duty to protect that Bo abandoned. Why did Bo put up with his son and his team being abused? To understand this, we need to dive deeper into the relationship between humiliation and shame.

People feel humiliated when someone else forces them into an undignified position or treats them as someone who doesn’t count, as contemptible or even beneath contempt. Humiliation is a response to how others treat oneself. People feel shame when they fail to measure up to social standards of esteem that they have internalized. One might feel ashamed for “allowing” another person to humiliate oneself, even if one had no way to avoid it. In that case, humiliation precedes shame. But there are many other causes of shame not predicated on humiliation.

Everyone agrees that a characteristic response to shame is to want to hide from the gaze of others. There are at least two characteristic responses to humiliation. (1) Getting even: restoring oneself to a position of (at least) equality with respect to the bullying party, often by means of violence. It took social change for lawsuits to provide a respectable nonviolent alternative. (2) Submission: like the dog who loses a fight and slinks away, tail between its legs.

According to the bullies’ patriarchal rules of real manhood, one’s manhood can be demeaned and one can thereby be humiliated by the humiliation of associates under one’s authority. This is explicit in honor cultures, where the honor of men is embodied in the sexual purity of their female relatives. A man can humiliate another man by raping or seducing his wife, daughter, sister, or niece. Female relatives humiliate the men responsible for them by choosing to have sex outside of an approved marriage. Others mock men for failing to protect and control their female relatives. Manly honor is thus deeply wrapped up in totalitarian control over their female relatives’ sexuality.

The same general logic applies in the U.S., but by somewhat different rules about who is responsible for whom and how they may respond. I think Bo felt humiliated by the fact that his son was raped. But he was a prisoner of the same bullies’ rules he enforced on his son and his team. So, instead of getting angry at Anderson, he got angry at his son. Instead of getting even with Anderson, he submitted, as called for by bullies’ rules. For, under the bullies’ rules of patriarchy, there is no real recovery or restoration of real manhood after such extreme humiliation (at least short of murdering Anderson in revenge). Once humiliated in such an extreme way, Bo felt he had no other option than to pretend that it never happened. And to avoid shame being heaped upon humiliation, he had to hope that no one discovered otherwise via the complaints of those whose victimization humiliated him. So he had to enforce the bullies’ rules of silence on them as well.

Johnson testified to the unrecoverability of a confident sense of manhood due to Anderson’s multiple sexual assaults throughout his football career. He said that he tried to prove to himself that he was a man by being excessively promiscuous. But penetrating countless women could never make up for his having been penetrated against his will, and thereby forced into a position of feminine submission. He destroyed two marriages in his futile attempts to restore his sense of manhood, and was unable to establish stable intimate relationships.

Rape culture is the popular enforcement of bullies’ rules against those traumatized by the sexual humiliation of bullies. Bo didn’t scream over his son’s rape, because he didn’t want shame heaped upon his humiliation. And that is often why women don’t scream either. Although Bo’s “toughen up” reprimand implies that he thought silent submission was a specifically manly way to respond to rape, in reality bullies’ rules prescribe the same conduct for women–silent submission.

I draw two lessons from this analysis. First, many men are victims of rape culture too. More generally, they are victims of bullies’ rules of patriarchy. Bullies’ rules are the actual rules by which patriarchy operates, in contrast with the legitimizing patriarchal ideology that Glenn believed in. Second, and more generally, Bo’s response to the numerous rapes of his son and his athletes strongly supports Robin Dembroff’s analysis of patriarchy. According to Dembroff, patriarchy does not place all men above all women. It places “real men” above everyone else, at everyone else’s expense.

Trumpism is another manifestation of the popular enforcement of bullies’ rules against all varieties of humiliation inflicted by Trump against his enemies and associates. If you want to know why so few GOP officeholders, party officials, and Trump aides and associates scream even when Trump humiliates them or the people they love, just remember why Bo didn’t scream when his son was raped. Bullies can’t enforce their own rules all by themselves. They need support from others.

A few weeks ago, Daniel Dennett published an alarmist essay (“Creating counterfeit digital people risks destroying our civilization”) in The Atlantic that amplified concerns Yuval Noah Harari expressed in the Economist.+ (If you are in a rush, feel free to skip to the next paragraph because what follows are three quasi-sociological remarks.) First, Dennett’s piece is (sociologically) notable because in it he is scathing of the “AI community” (many of whom are his fanbase) and its leading corporations (“Google, OpenAI, and others”). Dennett’s philosophy has not been known for leading one to a left-critical political economy, and neither has Harari’s. In addition, Dennett’s piece is psychologically notable because it goes against his rather sunny disposition — he is a former teacher and sufficiently regular acquaintance — and the rather optimistic persona he has sketched of himself in his writings (recall this recent post); alarmism just isn’t Dennett’s shtick. Third, despite their prominence neither Harari nor Dennett’s pieces really reshaped the public discussion (in so far as there (still) is a public). And that’s because it competes with the ‘AGI induced extinction’ meme, which, despite being a lot more far-fetched, is scarier (human extinction > fall of our civilization) and is much better funded and supported by powerful (rent-seeking) interests.

Here’s Dennett’s core claim(s):

You may ask, ‘What does this have to do with the intentional stance?’ For Dennett goes on to write, “Our natural inclination to treat anything that seems to talk sensibly with us as a person—adopting what I have called the “intentional stance”—turns out to be easy to invoke and almost impossible to resist, even for experts. We’re all going to be sitting ducks in the immediate future.” This is a kind of (or at least partial) road to serfdom thesis produced by our disposition to take up the intentional stance. In what follows I show how these concepts come together by the threat posed by AIs designed to fake personhood.

More than a half century ago, Dan Dennett re-introduced a kind of (as-if) teleological explanation into natural philosophy by coining and articulation (over the course of a few decades of refinement), the ‘intentional stance’ and its role in identifying so-called ‘intentional systems,’ which just are those entities to which ascription of the intentional stance is successful. Along the way, he gave different definitions of the intentional stance (and what counts as success). But here I adopt the (1985) one:

It is a familiar fact from the philosophy of science that prediction and explanation can come apart.* I mention this because it’s important to see that the intentional stance isn’t mere or brute instrumentalism. The stance presupposes prediction and explanation as joint necessary conditions.

In the preceding two I have treated the intentional stance as (i) an explanatory or epistemic tool that describes a set of strategies for analyzing other entities (including humans and other kinds of agents) studied in cognitive science and economics (one of Dennett’s original examples).** But as the language of ‘stance’ suggests and as Dennett’s examples often reveal the intentional stance also describes our own (ii) ordinary cognitive practice even when we are not doing science. In his 1971 article, Dennett reminds the reader that this is “easily overlooked.” (p.93) For, Dennett the difference between (i-ii) is one of degree (this is his debt to his teacher Quine, but for present purposes it useful to keep them clearly distinct (and when I need to disambiguate I will use ‘intentional stance (i)’ vs ‘intentional stance (ii).’)

Now, as Dennett already remarked in his original (1971) article, but I only noticed after reading Rovane’s (1994) “The Personal Stance,” back in the day, there is something normative about the intentional stance because of the role of rationality in it (and, as Dennett describes, the nature of belief). And, in particular, it seems natural that when we adopt the intentional stance in our ordinary cognitive practice we tacitly or explicitly ascribe personhood to the intentional system. As Dennett puts it back in 1971, “Whatever else a person might be-embodied mind or soul, self-conscious moral agent, “emergent” form of intelligence-he is an Intentional system, and whatever follows just from being an Intentional system thus is true of a person.” Let me dwell on a complication here.

That, in ordinary life, we are right to adopt the intentional stance toward others is due to the fact that we recognize them as persons, which is a moral and/or legal status. In fact, we sometimes even adopt the intentional stance(ii) in virtue of this recognition even in high stakes contexts (e.g., ‘what would the comatose patient wish in this situation?’) That we do so may be the effect of Darwinian natural selection, as Dennett implies, and that it is generally a successful practice may also be the effect of such selection. But it does not automatically follow that when some entity is treated successfully as an intentional system it thereby is or even should be a person. Thus, whatever follows just from being an intentional system is true of a person, but (and this is the complication) it need not be the case that what is true of a person is true of any intentional system. So far so good. With that in place let’s return to Dennett’s alarmist essay in The Atlantic, and why it instantiates, at least in part, a road to serfdom thesis.

At a high level of generality, a road to serfdom thesis holds (this is a definition I use in my work in political theory) that an outcome unintended to social decisionmakers [here profit making corporations and ambitious scientists] is foreseeable to the right kind of observer [e.g., Dennett, Harari] and that the outcome leads to a loss of political and economic freedom over the medium term. I use ‘medium’ here because the consequences tend to follow in a time frame within an ordinary human life, but generally longer than one or two years (which is the short-run), and shorter than the centuries’ long process covered by (say) the rise and fall of previous civilization. (I call it a ‘partial’ road to serfdom thesis because a crucial plank is missing–see below.)

Before I comment on Dennett’s implied social theory, it is worth noting two things (and the second is rather more important): first, adopting the intentional stance is so (to borrow from Bill Wimsatt) entrenched into our ordinary cognitive practices that even those who can know better (“experts”) will do so in cases where they may have grounds to avoid doing so. Second, Dennett recognizes that when we adopt the intentional stance(ii) we have a tendency to confer personhood on the other (recall the complication.) This mechanism helps explain, as Joshua Miller observed, how that Google engineer fooled himself into thinking he was interacting with a sentient person.

Of course, a student of history, or a reader of science fiction, will immediately recognize that this tendency to confer personhood on intentional systems can be highly attenuated. People and animals have been regularly treated as things and instruments. So, what Dennett really means or ought to mean is that we will (or are) encounter(ing) intentional systems designed (by corporations) to make it likely that we will automatically treat them as persons. Since Dennett is literally the expert on this, and has little incentive to mislead the rest us on this very issue, it’s worth taking him seriously and it is rather unsettling that even powerful interests with a manifest self-interest in doing so are not.

Interestingly enough, in this sense the corporations who try to fool us are mimicking Darwinian natural selection because as Dennett himself has emphasized decades ago when the robot Cog was encountered in the lab, we all ordinarily have a disposition to treat, say, even very rudimentary eyes following/staring at us as exhibiting agency and as inducing the intentional stance into us. Software and human factor engineers have been taking advantage of this tendency all along to make our gadgets and tools ‘user friendly.’