“There are good reasons to think that some AIs today have wellbeing.”

In this guest post, Simon Goldstein (Dianoia Institute, Australian Catholic University) and Cameron Domenico Kirk-Giannini (Rutgers University – Newark, Center for AI Safety) argue that some existing artificial intelligences have a kind of moral significance because they’re beings for whom things can go well or badly.

This is the sixth in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Posts in the summer guest series will remain pinned to the top of the page for the week in which they’re published.]

We recognize one another as beings for whom things can go well or badly, beings whose lives may be better or worse according to the balance they strike between goods and ills, pleasures and pains, desires satisfied and frustrated. In our more broad-minded moments, we are willing to extend the concept of wellbeing also to nonhuman animals, treating them as independent bearers of value whose interests we must consider in moral deliberation. But most people, and perhaps even most philosophers, would reject the idea that fully artificial systems, designed by human engineers and realized on computer hardware, may similarly demand our moral consideration. Even many who accept the possibility that humanoid androids in the distant future will have wellbeing would resist the idea that the same could be true of today’s AI.

Perhaps because the creation of artificial systems with wellbeing is assumed to be so far off, little philosophical attention has been devoted to the question of what such systems would have to be like. In this post, we suggest a surprising answer to this question: when one integrates leading theories of mental states like belief, desire, and pleasure with leading theories of wellbeing, one is confronted with the possibility that the technology already exists to create AI systems with wellbeing. We argue that a new type of AI—the artificial language agent—has wellbeing. Artificial language agents augment large language models with the capacity to observe, remember, and form plans. We also argue that the possession of wellbeing by language agents does not depend on them being phenomenally conscious. Far from a topic for speculative fiction or future generations of philosophers, then, AI wellbeing is a pressing issue. This post is a condensed version of our argument. To read the full version, click here.

Artificial language agents (or simply language agents) are our focus because they support the strongest case for wellbeing among existing AIs. Language agents are built by wrapping a large language model (LLM) in an architecture that supports long-term planning. An LLM is an artificial neural network designed to generate coherent text responses to text inputs (ChatGPT is the most famous example). The LLM at the center of a language agent is its cerebral cortex: it performs most of the agent’s cognitive processing tasks. In addition to the LLM, however, a language agent has files that record its beliefs, desires, plans, and observations as sentences of natural language. The language agent uses the LLM to form a plan of action based on its beliefs and desires. In this way, the cognitive architecture of language agents is familiar from folk psychology.

For concreteness, consider the language agents built this year by a team of researchers at Stanford and Google. Like video game characters, these agents live in a simulated world called ‘Smallville’, which they can observe and interact with via natural-language descriptions of what they see and how they act. Each agent is given a text backstory that defines their occupation, relationships, and goals. As they navigate the world of Smallville, their experiences are added to a “memory stream” in the form of natural language statements. Because each agent’s memory stream is long, agents use their LLM to assign importance scores to their memories and to determine which memories are relevant to their situation. Then the agents reflect: they query the LLM to make important generalizations about their values, relationships, and other higher-level representations. Finally, they plan: They feed important memories from each day into the LLM, which generates a plan for the next day. Plans determine how an agent acts, but can be revised on the fly on the basis of events that occur during the day. In this way, language agents engage in practical reasoning, deciding how to promote their goals given their beliefs.

The conclusion that language agents have beliefs and desires follows from many of the most popular theories of belief and desire, including versions of dispositionalism, interpretationism, and representationalism.

According to the dispositionalist, to believe or desire that something is the case is to possess a suitable suite of dispositions. According to ‘narrow’ dispositionalism, the relevant dispositions are behavioral and cognitive; ‘wide’ dispositionalism also includes dispositions to have phenomenal experiences. While wide dispositionalism is coherent, we set it aside here because it has been defended less frequently than narrow dispositionalism.

Consider belief. In the case of language agents, the best candidate for the state of believing a proposition is the state of having a sentence expressing that proposition written in the memory stream. This state is accompanied by the right kinds of verbal and nonverbal behavioral dispositions to count as a belief, and, given the functional architecture of the system, also the right kinds of cognitive dispositions. Similar remarks apply to desire.

According to the interpretationist, what it is to have beliefs and desires is for one’s behavior (verbal and nonverbal) to be interpretable as rational given those beliefs and desires. There is no in-principle problem with applying the methods of radical interpretation to the linguistic and nonlinguistic behavior of a language agent to determine what it believes and desires.

According to the representationalist, to believe or desire something is to have a mental representation with the appropriate causal powers and content. Representationalism deserves special emphasis because “probably the majority of contemporary philosophers of mind adhere to some form of representationalism about belief” (Schwitzgebel).

It is hard to resist the conclusion that language agents have beliefs and desires in the representationalist sense. The Stanford language agents, for example, have memories which consist of text files containing natural language sentences specifying what they have observed and what they want. Natural language sentences clearly have content, and the fact that a given sentence is in a given agent’s memory plays a direct causal role in shaping its behavior.

Many representationalists have argued that human cognition should be explained by positing a “language of thought.” Language agents also have a language of thought: their language of thought is English!

An example may help to show the force of our arguments. One of Stanford’s language agents had an initial description that included the goal of planning a Valentine’s Day party. This goal was entered into the agent’s planning module. The result was a complex pattern of behavior. The agent met with every resident of Smallville, inviting them to the party and asking them what kinds of activities they would like to include. The feedback was incorporated into the party planning.

To us, this kind of complex behavior clearly manifests a disposition to act in ways that would tend to bring about a successful Valentine’s Day party given the agent’s observations about the world around it. Moreover, the agent is ripe for interpretationist analysis. Their behavior would be very difficult to explain without referencing the goal of organizing a Valentine’s Day party. And, of course, the agent’s initial description contained a sentence with the content that its goal was to plan a Valentine’s Day party. So, whether one is attracted to narrow dispositionalism, interpretationism, or representationalism, we believe the kind of complex behavior exhibited by language agents is best explained by crediting them with beliefs and desires.

What makes someone’s life go better or worse for them? There are three main theories of wellbeing: hedonism, desire satisfactionism, and objective list theories. According to hedonism, an individual’s wellbeing is determined by the balance of pleasure and pain in their life. According to desire satisfactionism, an individual’s wellbeing is determined by the extent to which their desires are satisfied. According to objective list theories, an individual’s wellbeing is determined by their possession of objectively valuable things, including knowledge, reasoning, and achievements.

On hedonism, to determine whether language agents have wellbeing, we must determine whether they feel pleasure and pain. This in turn depends on the nature of pleasure and pain.

There are two main theories of pleasure and pain. According to phenomenal theories, pleasures are phenomenal states. For example, one phenomenal theory of pleasure is the distinctive feeling theory. The distinctive feeling theory says that there is a particular phenomenal experience of pleasure that is common to all pleasant activities. We see little reason why language agents would have representations with this kind of structure. So if this theory of pleasure were correct, then hedonism would predict that language agents do not have wellbeing.

The main alternative to phenomenal theories of pleasure is attitudinal theories. In fact, most philosophers of wellbeing favor attitudinal over phenomenal theories of pleasure (Bramble). One attitudinal theory is the desire-based theory: experiences are pleasant when they are desired. This kind of theory is motivated by the heterogeneity of pleasure: a wide range of disparate experiences are pleasant, including the warm relaxation of soaking in a hot tub, the taste of chocolate cake, and the challenge of completing a crossword. While differing in intrinsic character, all of these experiences are pleasant when desired.

If pleasures are desired experiences and AIs can have desires, it follows that AIs can have pleasure if they can have experiences. In this context, we are attracted to a proposal defended by Schroeder: an agent has a pleasurable experience when they perceive the world being a certain way, and they desire the world to be that way. Even if language agents don’t presently have such representations, it would be possible to modify their architecture to incorporate them. So some versions of hedonism are compatible with the idea that language agents could have wellbeing.

We turn now from hedonism to desire satisfaction theories. According to desire satisfaction theories, your life goes well to the extent that your desires are satisfied. We’ve already argued that language agents have desires. If that argument is right, then desire satisfaction theories seem to imply that language agents can have wellbeing.

According to objective list theories of wellbeing, a person’s life is good for them to the extent that it instantiates objective goods. Common components of objective list theories include friendship, art, reasoning, knowledge, and achievements. For reasons of space, we won’t address these theories in detail here. But the general moral is that once you admit that language agents possess beliefs and desires, it is hard not to grant them access to a wide range of activities that make for an objectively good life. Achievements, knowledge, artistic practices, and friendship are all caught up in the process of making plans on the basis of beliefs and desires.

Generalizing, if language agents have beliefs and desires, then most leading theories of wellbeing suggest that their desires matter morally.

We’ve argued that language agents have wellbeing. But there is a simple challenge to this proposal. First, language agents may not be phenomenally conscious — there may be nothing it feels like to be a language agent. Second, some philosophers accept:

The Consciousness Requirement. Phenomenal consciousness is necessary for having wellbeing.

The Consciousness Requirement might be motivated in either of two ways: First, it might be held that every welfare good itself requires phenomenal consciousness (this view is known as experientialism). Second, it might be held that though some welfare goods can be possessed by beings that lack phenomenal consciousness, such beings are nevertheless precluded from having wellbeing because phenomenal consciousness is necessary to have wellbeing.

We are not convinced. First, we consider it a live question whether language agents are or are not phenomenally conscious (see Chalmers for recent discussion). Much depends on what phenomenal consciousness is. Some theories of consciousness appeal to higher-order representations: you are conscious if you have appropriately structured mental states that represent other mental states. Sufficiently sophisticated language agents, and potentially many other artificial systems, will satisfy this condition. Other theories of consciousness appeal to a ‘global workspace’: an agent’s mental state is conscious when it is broadcast to a range of that agent’s cognitive systems. According to this theory, language agents will be conscious once their architecture includes representations that are broadcast widely. The memory stream of Stanford’s language agents may already satisfy this condition. If language agents are conscious, then the Consciousness Requirement does not pose a problem for our claim that they have wellbeing.

Second, we are not convinced of the Consciousness Requirement itself. We deny that consciousness is required for possessing every welfare good, and we deny that consciousness is required in order to have wellbeing.

With respect to the first issue, we build on a recent argument by Bradford, who notes that experientialism about welfare is rejected by the majority of philosophers of welfare. Cases of deception and hallucination suggest that your life can be very bad even when your experiences are very good. This has motivated desire satisfaction and objective list theories of wellbeing, which often allow that some welfare goods can be possessed independently of one’s experience. For example, desires can be satisfied, beliefs can be knowledge, and achievements can be achieved, all independently of experience.

Rejecting experientialism puts pressure on the Consciousness Requirement. If wellbeing can increase or decrease without conscious experience, why would consciousness be required for having wellbeing? After all, it seems natural to hold that the theory of wellbeing and the theory of welfare goods should fit together in a straightforward way:

Simple Connection. An individual can have wellbeing just in case it is capable of possessing one or more welfare goods.

Rejecting experientialism but maintaining Simple Connection yields a view incompatible with the Consciousness Requirement: the falsity of experientialism entails that some welfare goods can be possessed by non-conscious beings, and Simple Connection guarantees that such non-conscious beings will have wellbeing.

Advocates of the Consciousness Requirement who are not experientialists must reject Simple Connection and hold that consciousness is required to have wellbeing even if it is not required to possess particular welfare goods. We offer two arguments against this view.

First, leading theories of the nature of consciousness are implausible candidates for necessary conditions on wellbeing. For example, it is implausible that higher-order representations are required for wellbeing. Imagine an agent who has first order beliefs and desires, but does not have higher order representations. Why should this kind of agent not have wellbeing? Suppose that desire satisfaction contributes to wellbeing. Granted, since they don’t represent their beliefs and desires, they won’t themselves have opinions about whether their desires are satisfied. But the desires still are satisfied. Or consider global workspace theories of consciousness. Why should an agent’s degree of cognitive integration be relevant to whether their life can go better or worse?

Second, we think we can construct chains of cases where adding the relevant bit of consciousness would make no difference to wellbeing. Imagine an agent with the body and dispositional profile of an ordinary human being, but who is a ‘phenomenal zombie’ without any phenomenal experiences. Whether or not its desires are satisfied or its life instantiates various objective goods, defenders of the Consciousness Requirement must deny that this agent has wellbeing. But now imagine that this agent has a single persistent phenomenal experience of a homogenous white visual field. Adding consciousness to the phenomenal zombie has no intuitive effect on wellbeing: if its satisfied desires, achievements, and so forth did not contribute to its wellbeing before, the homogenous white field should make no difference. Nor is it enough for the consciousness to itself be something valuable: imagine that the phenomenal zombie always has a persistent phenomenal experience of mild pleasure. To our judgment, this should equally have no effect on whether the agent’s satisfied desires or possession of objective goods contribute to its wellbeing. Sprinkling pleasure on top of the functional profile of a human does not make the crucial difference. These observations suggest that whatever consciousness adds to wellbeing must be connected to individual welfare goods, rather than some extra condition required for wellbeing: rejecting Simple Connection is not well motivated. Thus the friend of the Consciousness Requirement cannot easily avoid the problems with experientialism by falling back on the idea that consciousness is a necessary condition for having wellbeing.

We’ve argued that there are good reasons to think that some AIs today have wellbeing. But our arguments are not conclusive. Still, we think that in the face of these arguments, it is reasonable to assign significant probability to the thesis that some AIs have wellbeing.

In the face of this moral uncertainty, how should we act? We propose extreme caution. Wellbeing is one of the core concepts of ethical theory. If AIs can have wellbeing, then they can be harmed, and this harm matters morally. Even if the probability that AIs have wellbeing is relatively low, we must think carefully before lowering the wellbeing of an AI without producing an offsetting benefit.

[Image made with DALL-E]

Some related posts:

“Philosophers on GPT-3”

“Philosophers on Next-Generation Large Language Models”

“GPT-4 and the Question of Intelligence”

“We’re Not Ready for the AI on the Horizon, But People Are Trying”

“Researchers Call for More Work on Consciousness”

“Dennett on AI: We Must Protect Ourselves Against ‘Counterfeit People’”

“Philosophy, AI, and Society Listserv”

“Talking Philosophy with Chat-GPT“

The post A Case for AI Wellbeing (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

Salvatore Florio, currently reader in philosophy at the University of Birmingham, will be moving to the University of Oslo, where he will be associate professor of philosophy.

Professor Florio specializes in philosophy of language, philosophical logic, and philosophy of mathematics. He is the author, with Øystein Linnebo (Oslo), of The Many and the One: A Philosophical Study of Plural Logic (OUP, 2021), along with other works, which you can learn about here and here. He also serves as Coordinating Editor of The Review of Symbolic Logic.

In addition to his position at Birmingham, he is also a professorial fellow at Oslo. He takes up his new position at Oslo in September, 2023.

The post Florio from Birmingham to Oslo first appeared on Daily Nous.

A statement from philosophers in response to the knife attack on the professor and students in a philosophy of gender course at the University of Waterloo this week, in which they “affirm our commitment to academic freedom, and condemn all uses of violence, intimidation, or derogation that attempt to undermine philosophical examinations of gender and sexuality” has been published and is open for signatures by other members of the philosophical community.

The statement was authored by Robin Dembroff (Yale), Justin Khoo (MIT), and L.A. Paul (Yale). It states:

The statement is posted here. Those interested in adding their name to the list of signatories can do so via this form.

The post Statement from Philosophy Professors & Graduate Students on University of Waterloo Attack first appeared on Daily Nous.

Recent philosophy-related news.*

1. A new journal, Passion: the Journal of the European Philosophical Society for the Study of Emotions, has just published its inaugural issue. The journal is a peer-reviewed (double blind), open-access, biannual publication. Its editors-in-chief are Alfred Archer (Tilburg University) and Heidi Maibom (University of the Basque Country, University of Cincinnati). The first issue is here.

2. The popular nationally-syndicated radio program Philosophy Talk, co-hosted by Ray Briggs and Josh Landy (Stanford University), has been awarded a media production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to create “Wise Women,” a 16-episode series about women philosophers through the ages. The series, which will feature different guest scholars in conversation with the show’s hosts, begins on July 23rd with an episode on Hypatia.

3. Butler University just wrapped up its first ever philosophy camp for high school students. You can learn more about it here.

4. PhilVideos (previously), a project from researchers at the University of Genoa that aims to sift through the abundance of philosophy videos online and present an expert-curated and searchable selection of them, is now online (in beta). You can try it out here and read more about its features (including a more specific search interface) here. If you’re interested in becoming a reviewer for the site, you can find out about doing so here.

* Over the summer, many news items will be consolidated in posts like this.

The post Philosophy News Summary first appeared on Daily Nous.

“Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” the U.S. Supreme Court declared in a ruling today.

The New York Times reports:

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., writing for the 6-3 majority, said the two programs “unavoidably employ race in a negative manner” and “involve racial stereotyping,” in a manner that violates the Constitution. However, he added, universities can consider how race has affected an applicant’s life. Students, he wrote, “must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual — not on the basis of race.”

Citing the 2003 case of Grutter v. Bollinger, and referencing Justice Powell’s decision in the 1978 case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Roberts wrote:

The Grutter majority’s analysis tracked Justice Powell’s in many respects, including its insistence on limits on how universities may consider race in their admissions programs. Those limits, Grutter explained, were intended to guard against two dangers that all race-based government action portends. The first is the risk that the use of race will devolve into “illegitimate . . . stereotyp[ing].” Richmond v. J. A. Croson Co., 488 U. S. 469, 493 (plurality opinion). Admissions programs could thus not operate on the “belief that minority students always (or even consistently) express some characteristic minority viewpoint on any issue.” Grutter, 539 U. S., at 333 (internal quotation marks omitted). The second risk is that race would be used not as a plus, but as a negative—to discriminate against those racial groups that were not the beneficiaries of the race-based preference. A university’s use of race, accordingly, could not occur in a manner that “unduly harm[ed] nonminority applicants.” Id., at 341.

To manage these concerns, Grutter imposed one final limit on racebased admissions programs: At some point, the Court held, they must end. Id., at 342. Recognizing that “[e]nshrining a permanent justification for racial preferences would offend” the Constitution’s unambiguous guarantee of equal protection, the Court expressed its expectation that, in 25 years, “the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” Id., at 343. Pp. 19– 21.

(e) Twenty years have passed since Grutter, with no end to racebased college admissions in sight. But the Court has permitted racebased college admissions only within the confines of narrow restrictions: such admissions programs must comply with strict scrutiny, may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and must—at some point—end. Respondents’ admissions systems fail each of these criteria and must therefore be invalidated under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Pp. 21–34.

(1) Respondents fail to operate their race-based admissions programs in a manner that is “sufficiently measurable to permit judicial [review]” under the rubric of strict scrutiny. Fisher v. University of Tex. at Austin, 579 U. S. 365, 381. First, the interests that respondents view as compelling cannot be subjected to meaningful judicial review. Those interests include training future leaders, acquiring new knowledge based on diverse outlooks, promoting a robust marketplace of ideas, and preparing engaged and productive citizens. While these are commendable goals, they are not sufficiently coherent for purposes of strict scrutiny. It is unclear how courts are supposed to measure any of these goals, or if they could, to know when they have been reached so that racial preferences can end. The elusiveness of respondents’ asserted goals is further illustrated by comparing them to recognized compelling interests. For example, courts can discern whether the temporary racial segregation of inmates will prevent harm to those in the prison, see Johnson v. California, 543 U. S. 499, 512–513, but the question whether a particular mix of minority students produces “engaged and productive citizens” or effectively “train[s] future leaders” is standardless.

Second, respondents’ admissions programs fail to articulate a meaningful connection between the means they employ and the goals they pursue. To achieve the educational benefits of diversity, respondents measure the racial composition of their classes using racial categories that are plainly overbroad (expressing, for example, no concern whether South Asian or East Asian students are adequately represented as “Asian”); arbitrary or undefined (the use of the category “Hispanic”); or underinclusive (no category at all for Middle Eastern students). The unclear connection between the goals that respondents seek and the means they employ preclude courts from meaningfully scrutinizing respondents’ admissions programs.

The universities’ main response to these criticisms is “trust us.” They assert that universities are owed deference when using race to benefit some applicants but not others. While this Court has recognized a “tradition of giving a degree of deference to a university’s academic decisions,” it has made clear that deference must exist “within constitutionally prescribed limits.” Grutter, 539 U. S., at 328. Respondents have failed to present an exceedingly persuasive justification for separating students on the basis of race that is measurable and concrete enough to permit judicial review, as the Equal Protection Clause requires. Pp. 22–26.

(2) Respondents’ race-based admissions systems also fail to comply with the Equal Protection Clause’s twin commands that race may never be used as a “negative” and that it may not operate as a stereotype. The First Circuit found that Harvard’s consideration of race has resulted in fewer admissions of Asian-American students. Respondents’ assertion that race is never a negative factor in their admissions programs cannot withstand scrutiny. College admissions are zerosum, and a benefit provided to some applicants but not to others necessarily advantages the former at the expense of the latter.

Respondents admissions programs are infirm for a second reason as well: They require stereotyping—the very thing Grutter foreswore. When a university admits students “on the basis of race, it engages in the offensive and demeaning assumption that [students] of a particular race, because of their race, think alike.” Miller v. Johnson, 515 U. S. 900, 911–912. Such stereotyping is contrary to the “core purpose” of the Equal Protection Clause. Palmore, 466 U. S., at 432. Pp. 26– 29.

(3) Respondents’ admissions programs also lack a “logical end point” as Grutter required. 539 U. S., at 342. Respondents suggest that the end of race-based admissions programs will occur once meaningful representation and diversity are achieved on college campuses. Such measures of success amount to little more than comparing the racial breakdown of the incoming class and comparing it to some other metric, such as the racial makeup of the previous incoming class or the population in general, to see whether some proportional goal has been reached. The problem with this approach is well established: “[O]utright racial balancing” is “patently unconstitutional.” Fisher, 570 U. S., at 311. Respondents’ second proffered end point—when students receive the educational benefits of diversity—fares no better. As explained, it is unclear how a court is supposed to determine if or when such goals would be adequately met. Third, respondents suggest the 25-year expectation in Grutter means that race-based preferences must be allowed to continue until at least 2028. The Court’s statement in Grutter, however, reflected only that Court’s expectation that racebased preferences would, by 2028, be unnecessary in the context of racial diversity on college campuses. Finally, respondents argue that the frequent reviews they conduct to determine whether racial preferences are still necessary obviates the need for an end point. But Grutter never suggested that periodic review can make unconstitutional conduct constitutional. Pp. 29–34.

(f) Because Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points, those admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. At the same time, nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university. Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin. This Nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.

In her dissent, which Justices Kagan and Jackson joined, Justice Sotomayor writes:

Although progress has been slow and imperfect, race-conscious college admissions policies have advanced the Constitution’s guarantee of equality and have promoted Brown’s vision of a Nation with more inclusive schools. Today, this Court stands in the way and rolls back decades of precedent and momentous progress. It holds that race can no longer be used in a limited way in college admissions to achieve such critical benefits. In so holding, the Court cements a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter. The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society. Because the Court’s opinion is not grounded in law or fact and contravenes the vision of equality embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment, I dissent.

The whole decision is here. It is expected to affect educational admissions policies and practices across the country.

The post Supreme Court Declares Harvard’s and UNC’s Affirmative Action Programs Unconstitutional first appeared on Daily Nous.

Alastair Wilson, currently Professor of Philosophy at the University of Birmingham, has accepted a position as Professor of Philosophy at the University of Leeds.

Professor Wilson’s research is in philosophy of physics, metaphysics, philosophy of science, and epistemology. He is the author of The Nature of Contingency: Quantum Physics as Modal Realism (Oxford University Press, 2020), among many other works, which you can learn about here and here. You can read an interview with him here.

He takes up his new position at Leeds in September, 2023.

The post Wilson from Birmingham to Leeds first appeared on Daily Nous.

Three people were hospitalized following a knife attack that took place this afternoon in a University of Waterloo philosophy course. The suspect was arrested. No fatalities have been reported.

[original photo by Andrew Yang via UW Imprint, blurred]

The three victims, which include, according to the UW Imprint, the professor and two students, are in “non-life-threatening condition.”

The course meets in Hagey Hall, which is home to the university’s Department of Philosophy.

The UW Imprint reports that according to one student in the classroom when the attack took place, “a man of about 20-30 years of age entered the class and asked the professor what the class was about. The man closed the door, pulled two knives out of his backpack and proceeded to attack the professor. Students ran to the back of the class to exit out of the one class entrance.”

The University canceled classes in Hagey Hall for the remainder of the day but is expected to resume classes in the building tomorrow.

No charges against the suspect have been announced yet. The Waterloo Regional Police have said that “more information will be provided when available.”

UPDATES:

(a) The suspect has been identified as Geovanny Villalba-Aleman, age 24. He is a recent graduate of the university. He was charged with three counts of aggravated assault; four counts of assault with a weapon; two counts of possession of a weapon for a dangerous purpose; and mischief under $5,000, according to the National Post.

(b) The professor of the course, injured during the event, is associate professor of philosophy Katy Fulfer.

(c) “The accused targeted a gender-studies class and investigators believe this was a hate-motivated incident related to gender expression and gender identity,” Waterloo Regional Police wrote in a statement, according to CTV News.

(d) Global News reports on the account of the incident given by James Chow, a student who was in the classroom at the time of the attack:

He was in the second row of seating when he says a man with a backpack came into the room near the end of class and began to talk to the professor.

“He said to the teacher, ‘Oh, is this such and such psychology class?’ And the professor replied, ‘Oh no, you’re probably in the wrong class.’ Then he said, ‘Oh, what class is this?’ The professor replied, ‘This is a gender class’ or ‘philosophy of gender class.’”

Chow says the man asked if he could stay and the professor asked him to leave.

“While the man was listening to a reply, he put down his backpack in front of him at his feet, and he pulled out a knife. It still had like one of those sheaths or covers on it, like a plastic one.”

Upon hearing that it was a gender studies course, Chow says the man’s body language changed, as though he were “happy” to hear that he was in that class.

“The thing that disgusts me the most is this vile, mischievous smile that he had on his face and immediately the professor’s face just turned to like pure fear.”

Chow, who has been taking spring courses to catch up on prerequisites needed for his masters of philosophy, says his classmates began screaming as the suspect started to chase the professor down the middle of the classroom.“Our classroom is like a rectangle, but there’s only one entrance at the front where the man had entered and she ran to the back of the class. At this point, it was just pandemonium. Everyone was screaming.”

In the heat of the moment, Chow says he decided he needed to “at least attack him or injure him” so he says he threw a chair at the suspect as he cornered the professor in the back of the room. The professor was covering her face and screaming, Chow says.

“The next thing I know, I was running outside with a bunch of the other students and I was screaming to them like, ‘Get out of the building now.’”

The post Three Stabbed in Philosophy Course at Waterloo (multiple updates) first appeared on Daily Nous.

Simon Kirchin, currently Professor of Philosophy at the University of Kent, will be moving to the University of Leeds, where he will be Professor of Applied Ethics and Director of the Inter-disciplinary Applied Ethics (IDEA) Centre.

Professor Kirchin works in ethics, and is the author of Thick Evaluation (Oxford University Press, 2017; open access), among other works, which you can check out here and here.

He takes up his new position at Leeds in January, 2024.

The post Kirchin from Kent to Leeds first appeared on Daily Nous.

“We shouldn’t attempt to fit ‘outreach’ or ‘engagement’ into one of the existing three categories [of research, teaching, or service]. It doesn’t fit neatly into those categories. And, more importantly, all of us should be doing it as part of our jobs, not just a few of us. We are in an all-hands-on-deck situation.”

In the following guest post, Alex Guerrero, professor of philosophy at Rutgers University, argues that we should count engagement or outreach as a distinct component of the job of professor.

This is the fifth in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Posts in the summer guest series will remain pinned to the top of the page for the week in which they’re published.]

[“The Beautiful Walk” by René Magritte]

The job of a philosopher in America has been defined in relatively specific terms. These are the terms: research, teaching, and service. How much of one’s life one is expected to contribute to each, the precise percentage and weight, varies from job to job. In some, research is all that matters. In others, teaching is the thing. More rarely, a philosopher wanders deep into administration, lost in a forest of service, and emerges as a thoughtful if pesky manager and builder of things with varying degrees of value. For most of us, we are required to do all of these, more or less well, with more or less joy.

Socrates and Kongzi both might have, for once, been at a loss for words if forced to say whether they were doing research, teaching, or service. But we have contracts, faculty handbooks, promotion guidelines, and legalistic specifications of what we are required to do. None of us are employed as philosophers. We are employed as professors (lecturers, instructors). For the most part, our job is like that of other humanities professors, and unlike that of research scientists and others in STEM fields supported by grants, who do things like “buy out” of teaching and oversee research labs. For us, the job is the core three: research, teaching, and service.

Teaching is the very official role where we are in front of enrolled students, in a class that counts for credit, presenting material, devising and evaluating assignments, and figuring out ways for students to learn what we take to be important about the subject. Our teaching responsibilities are almost always defined by the number of courses taught per academic year, spread out over semesters or quarters, often specified in terms of level and number.

Research is publication. We might wish it were instead about ideas, figuring new things out, moving knowledge forward—regardless of whether that results in articles in peer-reviewed journals or books in academic presses. But we know better. You need 8 publications for tenure in B+ or better peer-reviewed journals. Or 1.5 per year on the tenure clock. Or whatever. What “counts” for research, and how much it counts, is usually clear, even if promotion requirements are rarely specified in detail. Post-tenure, although research productivity factors into further promotions and merit raises, the sense in which it is “required” becomes considerably murkier.

Service is what is required to keep up the pretense that universities and colleges are run by the faculty, rather than by a distinct managerial class. We “serve” on hiring committees, as undergraduate and graduate program administrators, on curriculum committees, on admissions committees, in organizing colloquia and events, in putting people forward and evaluating them for tenure and promotion, as chairs and vice-chairs, deans and deanlets, and on committees for every domain of human complaint and frustration—these are the core of internal, university service. We serve our departments, schools, colleges, and universities. Many of us expand beyond this to engage in service to the “profession”—running academic journals, professional associations, planning workshops and conferences, creating and supporting broad mentoring and inclusion efforts, and so on.

Most of us were just dropped into this world of research, teaching, and service. I’ve never seen anyone try to justify why these are the three parts of the job. As many have noted, they don’t fit together all that naturally. What makes one an amazing teacher might have nothing do with what makes for a groundbreaking researcher. And we almost expect that whatever makes us good at those things will make us inept at, or at least impatient with, most kinds of “service.” Our graduate training programs do very little to train us to teach, or to administer anything or manage anyone.

The explanation for the three branches seems to be a historically contingent one, with the modern college or university coming to exist with a dual-purpose mission of educating students (teaching) and advancing knowledge (research), and service comes along as a third thing essential to preserving various values relating to those first two. Specifically, the values of academic, expert peer review (for admissions, hiring, publication, research evaluation, promotion) and academic, expert curriculum and course design and implementation.

There are, of course, many ways of rethinking this basic three branch setup, and many institutions that have already reconfigured things so that people are hired into jobs where they will do just one or two of those three things. I don’t want to wade more deeply into those waters. Instead, I want to suggest that, given the pressures confronting colleges and universities, sustaining those institutions in their core dual-purpose mission of educating students and advancing knowledge requires introducing a fourth branch. I’m not sure what name for that fourth branch is best. Here are my two favorite candidates: outreach and engagement.

The basic argument for the fourth branch is simple.

Colleges and universities are supported (1) by the general public, through government funding; (2) by students and their families, through tuition and fees; and (3) by rich people, through donations. What education and what knowledge will be pursued in colleges and universities is not set in stone; it is, rather, a function of what those three groups want and demand. If we want philosophy to be part of the education and part of the knowledge that is pursued in the years to come, we need people in those three groups to want and demand philosophy. And for people in those three groups to want and demand philosophy, we need to reach out to them, engage them, make them aware of what philosophy is and why it is wonderful and valuable. Given what philosophy is, and given our contemporary situation, that task is monumental, and must be undertaken at many different levels, in many ways. No small number of us can do it on our own. Therefore, it should be a part of all of our jobs—quite literally—to do this work.

(We can substitute in almost any humanistic field for ‘philosophy’ in the above argument, with similar implications for a needed fourth branch for the rest of the humanistic fields.)

The basics of this ‘demand side’ story are familiar. Many students and parents think of college and university in terms of relatively short term, career ambitions—how will this major, this degree, this school help me get a job. Many states and nations have begun taking a similar attitude toward all higher education, thinking in terms of contribution to economic productivity. Little actual empirical investigation is involved in deciding that humanistic fields, and fields such as philosophy, in particular, don’t do well by this score. But that is a common public perception. And it is understandable. It seems plausible that a degree in business, health professions, computer science, engineering, or biomedical sciences (the five largest growth majors over the past ten years) would be a more direct route to a job than a degree in English, history, or philosophy (three of the majors that lost the most majors over the past ten years).

There are other factors that affect demand. STEM fields are intimately connected to industries and occupations outside of the academy, so that one might have encountered a person with background in that field. We no longer have the same kind of elite, quasi-aristocratic veneration of those humanistic things that every “educated” person must know. STEM spends more time in the news, as breakthroughs in tech, science, and computing get regular reporting and discussion, and result in products in our pockets and dreams on our screens. In the United States, quality exposure to literature, philosophy, and even history is rare prior to college or university, with many students not having encountered any philosophy before college, and having encountered history only as rote memorization and literature only as forced reading.

Behind the idea that colleges and universities have a dual-purpose mission of educating students and advancing knowledge is a mostly implicit idea about what education and knowledge is valuable and why. For those of us working as professors in a subject domain, we almost certainly see the domain as valuable, and can offer many different compelling reasons why it is valuable, pointing both to intrinsic or final value of the subject, and to instrumental benefits of education and knowledge in the domain. We can go on and on about personal transformation, what it means to be human, learning to think critically about what is important, becoming a democratic and cosmopolitan citizen of the world, and so forth. But for those not already in philosophy, where are they supposed to hear the good news?

It is easy to vilify the administrator class, focused on the bottom line—bottoms in seats, donations to “development” offices, legislative support for public institutions. But it is not their fault that higher education is funded as it is. It is not their fault that we, the professoriate, don’t have unbridled power to force people to study those subjects that we see as most valuable. Professors like the idea of being in control: we get to design the curriculum, plan the syllabus, pick the readings, develop the research projects, evaluate the work, decide what should be published, determine who should be admitted, hired, promoted, esteemed. This all seems right and good to us, given our knowledge and expertise. But that is not the system we have with respect to the very basic facts of higher education in most contemporary political environments. We might wish for administrators who could hold the line, fight the battle for us, make the case for the importance of philosophy and the humanities. And some of them can and do. But many operate in incredibly difficult economic and political environments. They can’t change the basic facts about whose demand matters. And they can’t even do much to affect the substance of what is in demand. They need help. And—at least given our knowledge—we are well positioned to provide it.

Many of us are already involved in various efforts to broaden exposure to and engagement with philosophy. Most involved in this work aren’t doing it thinking to “increase demand” for philosophy, but it plausibly has that effect. There are obviously central enterprises: exposing children and adolescents to philosophy and serious humanities in K-12 education, for example, something that many are already doing. Writing “public facing” philosophy that appears in newspapers, broad circulation prestige venues, trade books, and so on. Creating online philosophy courses and videos and other broad access materials like podcasts. There are also more local, more intimate efforts: organizing a public philosophy week at a public library, running a philosophy club or ethics bowl team at the local high school, organizing community book groups and “meetups” to discuss philosophy, running “ask a philosopher” booths at the train station, farmers’ market, or mall. These activities bring philosophy to people outside of the academy and bring people into philosophy, giving them entry points and a better sense of what the subject is and why it is of value. They also are a lot of fun. And a ton of work to do well. And, for the most part, they are treated as outside of one’s job, falling outside of the big three: research, teaching, and service.

For those involved in this work, a common argument is that it should be included under research, teaching, or service—depending on the details. In a few places, “engagement” work is already included as part of one’s official job requirements. In more places, efforts are being made to think about how to include this work under research, or teaching, or service. I’ve spent the past year on a committee at Rutgers on a “Task Force for Community Engaged/ Publicly Engaged Scholarship,” focused on questions of definition (what is it, what counts) and evaluation (what metrics are available and appropriate, what standards should be used) of this kind of research. In serving on this committee, I’ve learned in detail about dozens of similar efforts at other institutions. In almost every case, the discussion is focused on how to credit the work being done by a small percentage of professors who are doing some “community engagement” or “public facing” work. Can it count instead of other, more traditional academic research? Can it count for teaching or service?

I want to suggest that, for those of us in the humanities, we should understand the importance of this engagement work to our core dual mission of educating students and advancing knowledge in our fields, and we should stop trying to shoehorn it into the traditional three categories. In the same way that service is required to sustain certain valuable features of how education and research is conducted, engagement is required to sustain certain valuable features of what education and research is conducted. Professorial “service” is required due to internal, contingent features of running a college or university, as something instrumentally important to enabling high quality education of students and to advancing serious research and knowledge. In the modern political and economic context most of us are in now, professorial “outreach” or “public engagement” is required due to external, contingent features of running a college or university, as something instrumentally important to enabling high quality education of students and to advancing serious research and knowledge in all academic domains that are of genuine value, including philosophy. We shouldn’t attempt to fit “outreach” or “engagement” into one of the existing three categories. It doesn’t fit neatly into those categories. And, more importantly, all of us should be doing it as part of our jobs, not just a few of us. We are in an all-hands-on-deck situation. It’s not clear that even this huge shift would be enough to save the humanities, but it affords more hope than doing nothing and just praying for favorable shifts in the demand curves.

So, the proposal is this. Add “engagement” or “outreach” as a fourth component of the job of professor, along with research, teaching, and service. The exact percentages might vary, as they already do, across institutions. One model might be 35% teaching, 35% research, 20% service, and 10% outreach. Just as with service, there would be a variety of ways of satisfying the requirement. And it might be assessed over several years, rather just in one particular year.

In addition to the familiar forms above—creating and running K-12 programs and clubs, public facing writing, online courses and spaces for public philosophy discussion, podcasts, local events and courses and reading groups at libraries and other community venues—there might be other work that would count. Creating and publicizing materials about philosophy and its intrinsic and instrumental value, developing materials to connect philosophy to prominent issues of the moment, connecting philosophy to locally popular elements of colleges and universities (such as college sports), strategically lobbying local and state political officials to help explain the value of philosophy and to think about ways in philosophy might be relevant or useful given their political agenda, developing white papers and strategic plans to encourage businesses and industries to seek out philosophy graduates and build philosophy alumni networks, even working on philosophy-related fundraising (either through or, where permitted, outside of, the development office). We need to do work at many different levels, in many different venues and spaces. New Yorker articles and popular books are important, but insufficient to reach or affect the very broad, heterogeneous communities whose interest and demand is relevant.

Just as with service (and teaching and research, for that matter), we shouldn’t expect that everyone will be equally good at or equally drawn to every aspect of outreach. And, just as with service, much of our evaluation of the work will be somewhat less precise than our evaluation of teaching or research. Norms and guidelines will need to be developed and adjusted over time. There is also the question, as with teaching and service, of how to train people to do this work well. Much of the work being done by committees like the one I’ve been on can be of help in thinking through these issues. None strike me as insurmountable.

The basic hope is that, by requiring everyone to do some outreach and engagement work, we can get many more people involved, and have a correspondingly greater effect on the broad understanding of philosophy and its value, with a hoped-for uptick in interest, support, and demand.

There are other potential side-benefits to creating the fourth branch. One is that it might mean that the public face of philosophy will be much more complex and multifaceted, so that it isn’t entirely dominated by a few prominent people who are skilled at prestige publishing or personal branding or whatever we want to call Žižek’s skillset. Another is that, as most people who have done this work will attest, engagement and outreach work provides a kind of beneficial feedback, potentially improving the quality of one’s teaching, research, and service, as one steps back from those activities and considers and attempts to communicate about their value, and to share philosophy with people who have not encountered it before. A third is that it might enable and prepare philosophers and other humanists to push back more effectively against the tendency for humanistic and normative concerns to be overrun by the march of technological, scientific, and commercial “progress” and “innovation.” And it might help the broader public see, raise, and respond to these concerns for themselves, even without any university training in the field.

There might be a worry that focusing on demand and broad interest sets up a zero-sum competition. We might do better, but that will mean some other field, perhaps with a harder case to make, will do worse. Perhaps, although I think a broad push from humanists in this regard might make a considerable difference to public understanding and public perception, even about the basic role of colleges and universities and the value of attending those institutions. Much greater, more structurally supported and organized efforts from professors in this regard might help alter the discussion and push back against the view of higher education as just some kind of pre-vocational training for those who can afford it. Most optimistically, it might alter the public funding dynamics of college and university, reasserting the ideal of affordable liberal arts, humanistic higher education for all as part of an important public component of a genuinely democratic, flourishing society.

Earlier, I mentioned that administrators are often limited in the ways in which they can help us. Here is one: help the humanists help themselves, by building a fourth branch, focused on engagement and outreach, into our jobs. In some cases, we could begin doing this somewhat informally within departments, setting up service positions focused on outreach, and then treating that work as part of service. But, in my view, it will be better to build it in more structurally, with a broader requirement for everyone, and allowing a broader array of ways in which to contribute.

If we want philosophy to survive, we need people to understand what it is and why it should survive. We can’t just rest on our historical laurels or on “get off my lawn” arguments that simply insist that no serious university can exist without a philosophy department. We might be right. But we also might just end up surrounded by unserious universities.

Other posts on public philosophy, engagement, and outreach.

The post The Fourth Branch (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

Utrecht University has hired 11 new philosophers.

They have each been hired as “Universitair Docent,” which is a permanent position, pending a standard one-year probationary period.

(The following information has been supplied by Daniel Cohnitz, head of the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Utrecht.)

Uğur Aytaç will be appointed in the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Political Philosophy of Technology in September 2023. He will be a PPE Core Teacher.

Marie Chabbert will join the History of Philosophy group as universitair docent for History of Modern Philosophy.

Sanneke de Haan will be appointed in the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Ethics, starting September, 2023, while continuing her 0.2 FTE appointment as Socrates Professor of Psychiatry and Philosophy at the Erasmus School of Philosophy & Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam (funded by the Stichting Psychiatrie en Filosofie).

Jamie Draper was appointed in 2022 and will take up a position at the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Political Philosophy and Environmental Ethics, starting September 2023.

Chiara Lisciandra will be appointed in the Theoretical Philosophy group as universitair docent for Practical Reasoning, starting September 2023.

Uwe Peters will be appointed jointly in the Theoretical Philosophy group and the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence, starting October, 2023.

Carina Prunkl will be appointed in the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Ethics of Technology, December 2023.

Janis Schaab will be appointed in the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Moral, Political, and Social Philosophy, starting September 2023.

Emily Sullivan will be appointed in in the Theoretical Philosophy group as universitair docent for Philosophy of Science.

Juri Viehoff will be appointed in the Ethics Institute as universitair docent for Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, September 2023. He will be a PPE Core Teacher.

Sarah Virgi will be appointed jointly in the department’s History of Philosophy group and in Islam and Arabic Studies as universitair docent for Islamic Philosophy.

You can learn more about philosophy at Utrecht here.

The post Utrecht Hires 11 New Philosophers first appeared on Daily Nous.

In 1998, after a day lecturing at a conference on consciousness, neuroscientist Christof Koch (Allen Institute) and philosopher David Chalmers made a bet.

They were in “a smoky bar in Bremen,” reported Per Snaprud, “and they still had more to say. After a few drinks, Koch suggested a wager. He bet a case of fine wine that within the next 25 years someone would discover a specific signature of consciousness in the brain. Chalmers said it wouldn’t happen, and bet against.”

It has now been 25 years, and Mariana Lenharo, writing in Nature, reports that both of the researchers “agreed publicly on 23 June, at the annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in New York City, that it is still an ongoing quest—and declared Chalmers the winner.”

One thing that helped settle the bet, Lenharo writes, was the recent testing of two different theories about “the neural basis of consciousness”:

Integrated information theory (IIT) and global network workspace theory (GNWT). IIT proposes that consciousness is a ‘structure’ in the brain formed by a specific type of neuronal connectivity that is active for as long as a certain experience, such as looking at an image, is occurring. This structure is thought to be found in the posterior cortex, at the back of the brain. On the other hand, GNWT suggests that consciousness arises when information is broadcast to areas of the brain through an interconnected network. The transmission, according to the theory, happens at the beginning and end of an experience and involves the prefrontal cortex, at the front of the brain.

Six labs tested both of the theories, but the results did not “perfectly match” either of them.

Koch reportedly purchased a “a case of fine Portuguese wine” for Chalmers.

The post Winning Bet: Consciousness Still a Mystery first appeared on Daily Nous.

The administration of Simmons University has said that it is planning to close the school’s Department of Philosophy and end its major program.

Philosophy is one of several departments targeted.

“No decisions are final yet,” reports The Boston Globe, adding that “a final plan will be presented to the university’s board in October after university leaders meet with all departments.”

The university, which is women-only at the undergraduate level (but not for its graduate degrees), is facing financial constraints owed partly to what seems like a very bad deal it made with the online learning company 2U, according to which the company gets 50 to 62 percent of the tuition paid by each student in its online programs. According to the Globe, more than half of Simmons’ graduate students are in such online programs. The contract with 2U was made in 2013 and renewed (!) in 2018 for another 21 years.

Faculty were apparently instructed by the administration not to talk to the press. One professor, speaking anonymously to the Globe, says: “Cutting out the humanities and social sciences is like cutting out the heart and then seeing if the body will still walk.”

The current president of Simmons, Lynn Perry Wooten, has an academic specialization in “crisis leadership.”

The post Philosophy Threatened at Simmons University first appeared on Daily Nous.

Professors (and graduate students) occasionally get asked, “should I go to graduate school in philosophy?”

In a recent episode of the Overthink Podcast, philosophy professor co-hosts Ellie Anderson (Pomona) and David Peña-Guzmán (San Francisco State) take up this question. Watch below, and feel free to comment with points you think someone asking this question should consider.

Some related posts:

The post “Should I Go To Graduate School in Philosophy?” first appeared on Daily Nous.

Kenny Easwaran, who until recently was professor in the Department of Philosophy at Texas A&M University, has accepted a position as associate professor in the Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science at the University of California, Irvine.

Professor Easwaran works in epistemology, decision theory, and philosophy of math, and related areas. You can learn more about his research here and here.

He takes up his new position at Irvine this summer.

The post Easwaran from Texas A&M to UC Irvine first appeared on Daily Nous.

“When my younger self complained angrily in the margins with scrawls of ‘where is this going?’, he missed the sights and insights that the journey itself provided.”

A kind of philosophical innocence is the subject of the following guest post by Bradford Skow, Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Skow works mainly in metaphysics, philosophy of science, and aesthetics, and has a blog/newsletter, Mostly Aesthetics, on Substack, which I highly recommend.

This is the fourth in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Posts in the summer guest series will remain pinned to the top of the page for the week in which they’re published.]

Herbert Morris read an essay titled “Lost Innocence” at the 1975 Oberlin Philosophy Colloquium. In it, he attempted an analysis of Adam and Eve’s loss of innocence, when Eve was tempted and they ate from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The knowledge they acquired was not, obviously, perceptual knowledge, nor did they draw some new conclusion from their evidence. It is closer to say, Morris thought, that they acquired “a different way of feeling about what had been before them all along”: “[w]hereas one had earlier felt at ease, felt a kind of natural joy, one now is cursed with an absence of joy, perhaps more, with feeling anxious and bad.” But this itself is just a first approximation, and Morris steers us toward, and then away from, several more accounts of lost innocence, until, after a pause at his preferred one, he closes with a meditation on the nature of evil, and on the morally wise people who have “not been crushed by what they have confronted, but have emerged, in ways mysterious to behold, victorious, capable, despite and because of knowledge, of affirming rather than denying life.” Life-affirmation is not an ending that the essay’s opening paragraphs point you toward. Morris announces only that the essay was stimulated by reflection on the story of Adam and Eve, and he acknowledges early on the “serpentine nature” of his reasoning.

Every age has its favored philosophical templates. Readers of this venue are doubtless familiar, either as writers, or as readers or referees, with one in common use today:

I will argue that P.

Lo, notice that I am now arguing that P.

Reminder that Modus Ponens is valid!

In conclusion, I have argued that P.

On top of all this meta-signposting, not to be neglected is the obligatory here is the plan for this paper, placed at the end of the Introduction, and skipped over by every reader. The basic unit of philosophy is taken to be the argument with numbered premises and labeled conclusion, as the proof is the basic unit of mathematics. Of course books and papers in mathematics also have definitions and explanatory insertions, nor do works of philosophy consist only of arguments—not even Spinoza’s Ethics—but everything is built around them.

At sea between college and graduate school, I pursued a self-directed course of philosophical study, and focus on the argument was the straw keeping me afloat. When chance scudded me into Peter Unger’s paper “The Problem of the Many,” therefore, it seemed scandalous. “Although,” he wrote, “I think arguments are important in philosophy, my arguments here will be only the more assertive way for me to introduce the new problem, not the only way.” What an idea, that a philosophical goal could be achieved by other means.

I am just old enough to have had passed down to me, like myths of a lost age, other templates that were once more common. After his death, various collections of Wittgenstein’s notes and lectures were published, under titles like Remarks on Suchity-Such. A tradition began in which the basic unit of philosophy was—at least in presentation—the remark, sequences of which were presented in numbered paragraphs. On the surface this practice was more collegial and less aggressive, gentlemen (remember this was decades ago) lounging in tweed coats and exchanging thoughts between puffs of their pipes, but of course in reality a seemingly-anodyne “I would like to make a few remarks” was usually a preface to something devastating, or anyway intended to be so.

Because philosophy is so old, and because the ideas of the earliest philosophers are still alive today, it can seem that finding new philosophical positions, or new arguments for existing ones, requires a gold-medal performance, while those practicing other, newer disciplines languorously pick low-hanging fruit on their lunch breaks. I sometimes joke that, because of this, a career-making philosophical achievement can now consist in something as small as drawing a distinction. Or even in erasing one: I was once present when a famous philosopher complained, to the students in his graduate seminar, that one of his undergraduates could not grasp the distinction between numerical and qualitative identity, and I complained back that that student might just be a philosophical genius, seeing clearly that the alleged distinction Mr. Famous was trying to draw was not real. When Amos Tversky was a student, he chose psychology over philosophy in part because there were far fewer giants over whose shoulders one needed to see. However their eventual publications compare to Tversky’s Nobel-worthy life’s-work, I tell philosophy graduate students, they should take heart in the fact that he was a coward who could not muster the courage they have displayed.

Premise, premise, conclusion is the Freytag’s triangle of philosophy, and its de-throning in literary criticism may inspire. Jane Alison, in her book Meander, Spiral, Explode, explores a bunch of alternatives to the exposition, climax, resolution form, including the titular ones, which also makes good philosophical models. If Morris’s essay is a controlled and steady navigation by an experienced hand through a carefully surveyed territory, Arthur Danto is a great meanderer. In just the first few pages of The Transfiguration of the Commonplace he riffs on Euripidean and anti-Euripidean art, the imitation theory, and Sartre, and when my younger self complained angrily in the margins with scrawls of “where is this going?”, he missed the sights and insights that the journey itself provided.

The point is not, or not just, to have more fun, or to unleash unruly intellectual impulses that academic disciplines try to discipline. Form can be expressive in ways that matter aesthetically and even philosophically. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus sometimes achieves an austere oracular beauty that the philosophy-as-lab-report genre cannot equal and to which it cannot aspire. It is also, to some, offputtingly arrogant. To their temperament the Philosophical Investigations may be more congenial. “Bear in mind,” Kripke observed in Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language,

that Philosophical Investigations is not a systematic philosophical work where conclusions, once definitively established, need not be reargued. Rather, the Investigations is written as a perpetual dialectic, where persisting worries, expressed by the voice of an imaginary interlocutor, are never definitively silenced… the same ground is covered repeatedly, from the point of view of various special cases and from different angles, with the hope that the entire process will help the reader see the problems rightly.

If for Herbert Morris the loss of moral innocence was “like the loss of peace of mind accounted for by acquiring anxiety,” the form of the Investigations—as it struck Kripke anyway, as it presented itself to him—is expressive of a loss of philosophical innocence, and the—possibly appropriate—gnawing philosophical anxiety and uncertainty that some of us cannot shake, but may hope not to be crushed by.

The post Some Remarks on Form in Philosophy (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

The Philosophy Journal Insight Project (PJIP) “aims to provide philosophy researchers with practical insights on potential venues for publication.”

Its main offering is a spreadsheet that provides information about journals’ subject matter, word limits, type of peer review, open access status, rankings, impact information, acceptance rates, review times, reviewing quality, and so on.

Put together by Sam Andrews, a philosophy PhD student at the University of Birmingham, the site, which he says is a work in progress, currently has information about 47 journals.

You can check it out here.

The post New Site Collects and Standardizes Philosophy Journal Information first appeared on Daily Nous.

Recent philosophy-related news*, and a request…

1. Stephen Kershnar (SUNY Fredonia), whose February 2022 discussion of adult-child sex on the Brain in a Vat podcast sparked viral outrage and led to his removal from campus, has “filed a lawsuit this week in U.S. District Court in Buffalo asking the court to declare that Fredonia’s administrators violated his First Amendment rights by removing him from the classroom after the comments he made on a podcast kicked off a social-media firestorm,” according to the Buffalo News. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) has filed the lawsuit on his behalf, Kershnar says.

UPDATE: Here is the lawsuit and the motion for injunction (via Stephen Kershnar).

2. The editors of Philosophy, the flagship journal of The Royal Institute of Philosophy, have announced the winners of their 2022 Essay Prize, which was on the topic of emotions. They are: Renee Rushing (Florida State) for her “Fitting Diminishment of Anger: A Permissivist Account” and Michael Cholbi for his “Empathy and Psychopaths’ Inability to Grieve.” Mica Rapstine (Michigan) was named the runner-up for his “Political Rage and the Value of Valuing.” The prize of £2500 will be shared between the winners, and all three essays will be published in the October 2023 issue of the journal.

3. Some philosophers are on the new Twitter alternative, Bluesky. Kelly Truelove has a list of those with over 50 followers here. And yes, you can find me (and Daily Nous) on it.

4. One philosopher is among the new members of The American Philosophical Society, a learned society that aims to “honor and engage leading scholars, scientists, and professionals through elected membership and opportunities for interdisciplinary, intellectual fellowship.” It is John Dupré of the University of Exeter, who specializes in philosophy of science. The complete list of new members is here. Professor Dupré joins just 21 other philosophers that have been elected into the society since 1957 (the society was founded in 1743).

5. I’ve decided that some news items I had been planning to include in these summary posts over the summer should instead get their own posts. These are posts about philosophers’ deaths and faculty moves. Regarding the former, it would be wonderful if individuals volunteered to write up memorial notices for philosophers they knew, or whose work they are familiar with, including at least the kinds of information I tend to include in these posts (see here). Recently, philosophers Henry Allison, Richard W. Miller, and Donald Munro have died. If you are interested in writing up a memorial notice for one of them, please email me. Generally, over the summer, these posts and faculty move notices may take longer to appear than usual.

* Over the summer, many news items will be consolidated in posts like this.

The post Philosophy News Summary (updated) first appeared on Daily Nous.

“Analytic philosophy gradually substitutes an ersatz conception of formalized ‘rigor’ in the stead of the close examination of applicational complexity.”

In the following guest post, Mark Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, argues that a kind of rigor that helped philosophy serve a valuable role in scientific inquiry has, in a sense, gone wild, tempting philosophers to the fruitless task of trying to understand the world from the armchair.

This is the third in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

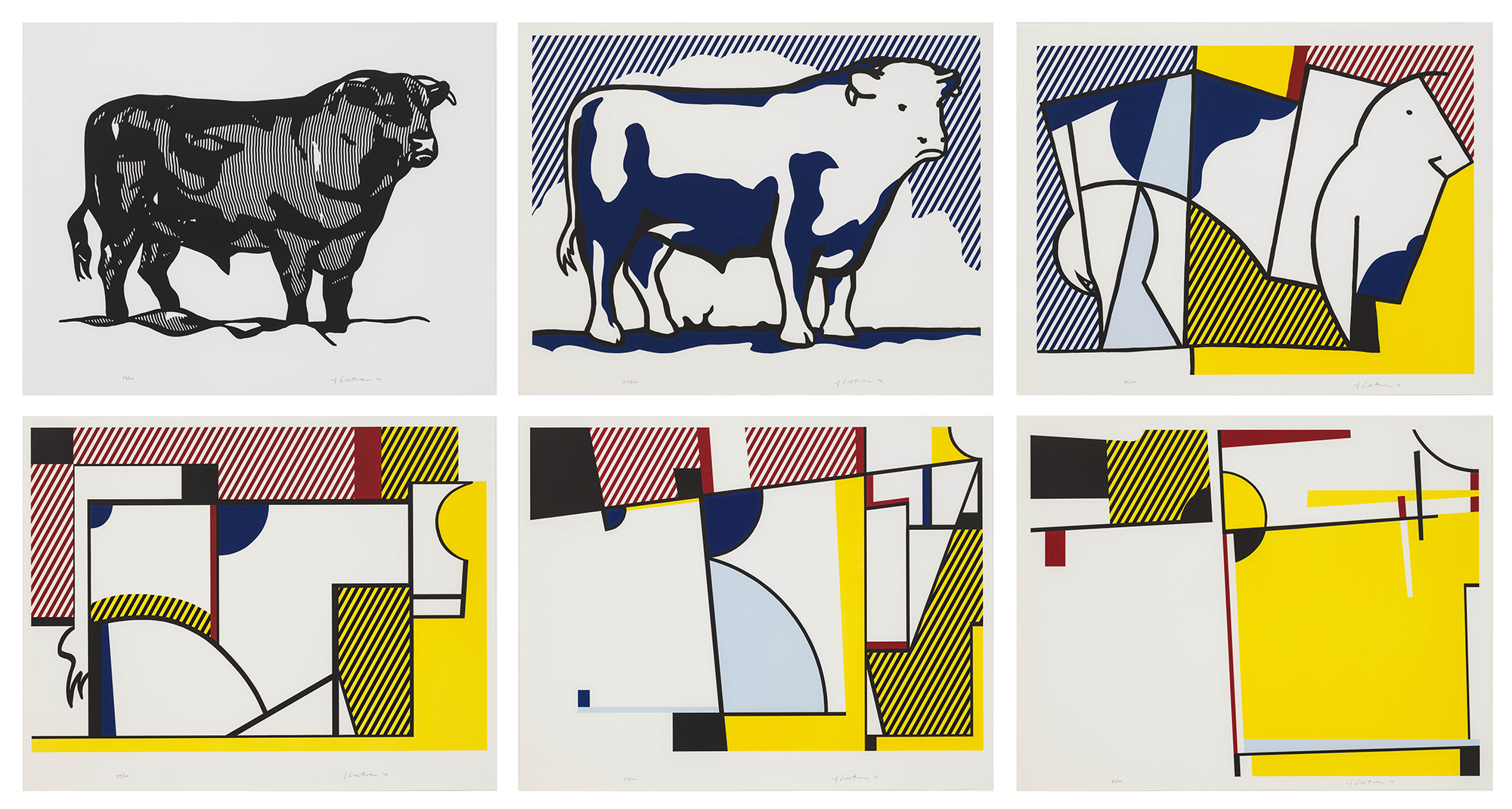

[Roy Lichtenstein, “Bull Profile Series”]

In the course of attempting to correlate some recent advances in effective modeling with venerable issues in the philosophy of science in a new book (Imitation of Rigor), I realized that under the banner of “formal metaphysics,” recent analytic philosophy has forgotten many of the motivational considerations that had originally propelled the movement forward. I have also found that like-minded colleagues have been similarly puzzled by this paradoxical developmental arc. The editor of Daily Nous has kindly invited me to sketch my own diagnosis of the factors responsible for this thematic amnesia, in the hopes that these musings might inspire alternative forms of reflective appraisal.