“Are you seriously telling me that this hot mash of mushrooms and fruit is going to completely heal his wounds?” (Gilbert 2019)

It is summer 2020 and I, like many others, am sequestered indoors clutching my recently acquired Nintendo Switch playing Animal Crossing: New Horizons (ACNH). In wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, people around the world seemed to swarm either to their handy technological devices or towards the soothing arms of nature. Luckily for me, my technological device included encounters with some virtual greenery—the trees and flowers of my beloved tropical Animal Crossing island.

Thao and Zucker having a nighttime picnic in Animal Crossing: New Horizons (Screen shot by Author)

As I planted my strategically planned flower beds and traveled from mystery island to island collecting fruits which I didn’t have, I also consulted many online forums for guidance. To my surprise, I stumbled upon PETA’s Vegan Guide to Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Within, I found several suggestions on how to play the game while supporting vegan ethics. My favourite part? The commentary on what foods within the game are vegan friendly. While nowadays it’s possible to cook a variety of dishes in ACNH (even seasonal varieties!) much of the early discourse on food in ACNH was about how powerful vegan diets are. In the game, you can literally dig up entire trees with the nourishment provided after eating a singular luscious virtual fruit. Sadly, this spurred some backlash from players arguing about: (1) the boundaries of our onlife and offline selves, (2) the potential of video games as pedagogy, and (3) the politics of digital and virtual foods. But how is it possible to extract all of these insights, politics, ethics, and social tensions from a game mimicking an agricultural life on a tropical waterfront property we all secretly desire during daydreams?

In this piece I apply my concept of Digital Food Spaces (DFS) or “online communities and platforms dedicated to the sharing of food-centered ideas and media” (Dam 2023) to the realm of video-gaming. I draw from both personal experiences and the insights of fellow gamers who I recruited via Twitter. Through our conversations I apply my theory into practice by analyzing the DFS of ACNH to examine how users conceptualize and interact with food in video games. Twitter (at its peak) had the capability to house and foster dialogues of every topic without reserve—food was just one of many, and as Schneider et al. (2018) has demonstrated, contentious discussion draws activist responses in the form of digital food activism by users.

From these conversations and interdisciplinary literature review I present three arguments:

Matt’s Animal Crossing: New Horizon character chats with Franklin, the Turkey Day chef. (Screen shot by Matt Fifield)

While there are video games whose sole focus is to highlight food and related processes like cooking and eating (e.g. Overcooked and Cooking Mama), I include all games which feature some aspect of food within its play and/or landscapes. I should clarify that even though something in a game is edible by characters, I try to focus on what we can colloquially code as “food” through its relatability to offline counterparts. Basically, a food is a food within a video game if its origins can be traced back to a particular food or food idea which exists offline to some degree.[1] This tracing is rather open, considering video games also feature mockeries of offline eats for several reasons. As a result, the boundaries of onlife (Van Est et al. 2014, Floridi et al. 2015) and offline in this piece are flexibly framed because they easily flow into one another and inevitably shape each other. As Floridi et al. (2015) emphasise, because ICTS[2] shape our (1) self conceptions, (2) mutual interactions, (3) realities, and (4) our interactions with reality, there are ongoing instances of boundary blurring between reality and virtuality as well as between humans, machines, and nature. Therefore, we can easily translate insights between the different realms and apply interventions and solutions accordingly—furthering the range of intimacy that technologies have with us presently and in the future (Van Est et al. 2014).

Digital Food Spaces (DFS) are not limited to social media sites and platforms, considering discussions about food take place almost everywhere online. Given that gaming (in practice and interest) continues to grow in popularity across age groups, it is essential that we include video games in our examinations of onlives and their capabilities of shaping the offline. Such insights are crucial for identifying and charting the transformations of how people are perceiving, understanding, and engaging with different foods—most especially when they allude to offline counterparts and processes.

A common feature which links many games together is the association of life/health points being replenished by consumable items in-game, much of which are stylized as food items. Gone are the days of only red health-boosting and blue mana-boosting potions—we’ve got entire menus of gourmet foods to fill player stats and inventories now.

This has led to much reactionary discussions and creations both online and offline. Entire online communities dedicate themselves to the recreation of these edibles in their own kitchens. Whether it’s a Reddit thread, a Facebook post, or a multi-video series on YouTube, gamers are experimenting with ways to bring the fantastical foods they encounter in their favorite games into their offline lives. Several dining establishments have also launched with these sentiments, but take a more reflexive approach through creating dishes inspired by in-game characters, locations, and items—for example the (unofficial) League of Legends restaurant “Challenger” based in China. However, for those of us who wish to capture the magic at home, there is also a growing video game cookbook collection which can teach you how to make foods from games like Destiny, The Elder Scrolls, World of Warcraft, the Fallout franchise, Sims, Minecraft, Street Fighter, and more.

Some games simulate the food production and preparation processes. In the Harvest Moon series, you’re a farmer with both crops and animals which grow and transform across the seasons. In several games it is possible to hunt creatures and cook them.[3] The Cooking Mama series allows us to pick recipes, prepare them step-by-step, and receive reviews on the final dishes. Overall, video games allow players several opportunities to critically consider and connect with foods and associated activities. This inevitably spurs discussion and prompts the formation and articulation of food-related opinions and perspectives among players. Within the DFS paradigm, video games are like entrées—catalysts of inspiration to explore and engage with foods in ways that go beyond the virtual.

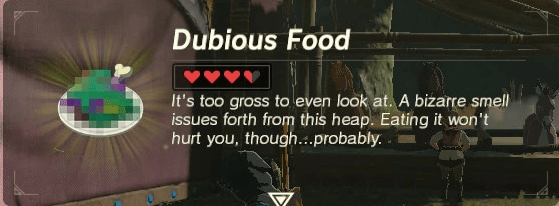

Video-gaming universes are seemingly infinite, in both creativity and vastness. Within, there are places for every wacky interaction and dream in between. We create our avatars from an assortment of options, and we attempt to explore the crevices of how we see (or would like to see) ourselves and the world through these choices. When given the tools (ICTs) in video games, we test the limits of what’s possible and appropriate. This logic extends to food in games as well. Think about so-called “dubious food” in the Legend of Zelda series:

“Dubious Food” from Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (Screen shot by Author)

“It’s too gross to even look at. A bizarre smell issues forth from this heap. Eating it won’t hurt you, though…probably” (In-game description, Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild 2017)

This food experimentation through hunting, gathering, and preparing foods often occurs in many explorational “open world” games, like The Elder Scrolls franchise and newer Pokémon games. For players, it provides a wider range of engagement and creativity with virtual foods while also providing insights into how cooking and mealtimes transform relationships between the player’s virtual body, their surroundings, and their in-game companions. VR games take this to the extreme by directly translating players’ physical movements into virtual simulations for added experiential depth. Hilariously, it is important to note that not all video game foods are helpful. Some creations also actively harm in-game health status and abilities, mirroring food poisoning experiences to some degree.

Video games easily initiate learning through vicarious consumption (Veblen 2007). As players encounter, prepare, and consume virtual foods, they increase their familiarity and knowledge around them (Staiano 2014). In turn, it sparks further curiosity and thinking around the foods and their offline cultural and historical inspirations. Often, players find this learned food-related information applicable in offline scenarios and conversations even in the cases where the foods are entirely fictional.

“Cooking foods in virtual reality has transferred over to what I apply in the kitchen. I used to bake bread but I got to know a number of pastries and deserts like tiramisu.” (personal communication, @Zay_ZYXWV)

“The Fallout games have all the disgusting foods. But also a lot of parodies of actual American snacks I guess. I don’t get all of them because I am from Germany, but I have a sense that they are versions of actual foods.” (personal communication, @PrimoRCavallo)

“I recently played the controversial Russian game Atomic Heart. One of the primary themes is the Soviet Union, and one of the main food factors which is a completely mandatory item for traversing the game is condensed milk, alongside bottles of vodka. I thought it was an odd choice for a power up item in a game, but after spending some time looking into it it seems like those two items had some high degree of value to the survival of those geographical people due to their long shelf life and stability in indeterminate situations.” (personal communication, @TheAbeg)

Considering many games have foods which are modeled after offline ones, they are useful for learning about foods outside of one’s experiential range. In the MMORPG MapleStory, many places which pay homage to real offline locations have their own special consumables that allude to local dishes, for example: satay, ramen, chili crab, unagi, bento boxes, steamed buns, dumplings, laksa, chicken rice, tacos, and curries. Several tropical fruits and snacks like durian, dragon fruit, dried squid, and dango are also available in-game.

Various food items found in MapleStory SEA. (Screen shot by Author)

Scholars across disciplines have stressed the importance of considering interlinking implications and applications of happenings online with those offline (Boellstorff 2016, Taylor and Nichter 2022). Analysing the interactions and engagements of our onlives within the DFS of gaming universes can provide information about points of interventions (e.g. cases of digital obesogenic environments) or the range of shared interests of certain groups as they pertain to food. While video-gaming only simulates life or death, the impacts of digital obesogenic environments has yet to be thoroughly explored. Video-gaming allows for people to embrace (if not overexaggerate) and explore aspects of their individual values and varied performances of self (Goffman 1959). It is of interest to those working in diplomacy, marketing, and the food industry to pay attention to the reception of foods in video game universes and players’ concerns as starting points for improvements in initiatives of gastrodiplomacy, product design, food communication, and more. Doing so would help generate more interactive and reflective national foods branding given the diversity of gaming communities (Ichijo et al. 2019, White et al. 2019, Dam 2023). Furthermore, there is immense potential to expand digital food studies’ research theories and methodologies in video games while also continuously challenging the boundaries of online and offline. If art does imitate life, how are we to ignore or deny the salience of how people play with and reimagine foods and foodscapes?

[1] An honorable mention for the “dubious food” available in Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

[2] Information and communication technologies

[3] There is an exhaustive amount of games where you can hunt creatures and eat them, so to list them all would be…well, exhaustive.

Atsuko Ichijo, Venetia Johannes, and Ronald Ranta. 2019. The Emergence of National Food: The Dynamics of Food and Nationalism. Bloomsbury.

Boellstorff, Tom. 2016. “For Whom the Ontology Turns: Theorizing the Digital Real.” Current Anthropology 57(4): 387-407.

Dam, Ashley T.K., 2023. “Dining with the Diaspora: Khmerican Digital Gastrodiplomacy”. Platypus Blog. https://blog.castac.org/2023/03/dining-with-the-diaspora-khmerican-digital-gastrodiplomacy/

Gayle, Latoya. 2020. “Nintendo fans mercilessly mock PETA for claiming vegans shouldn’t play Animal Crossing because it features virtual fishing and bug catching”. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-8155471/Video-game-players-mercilessly-mock-PETA-vegan-guide-Nintendos-Animal-Crossing.html

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Lynn, Lottie. 2021. “Animal Crossing Cooking: Ingredients and how to unlock cooking in New Horizons explained”. Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.net/animal-crossing-cooking-ingredients-how-unlock-new-horizons-8007

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals [PETA]. 2020. “PETA’s Vegan Guide to ‘Animal Crossing: New Horizons”. https://www.peta.org/features/animal-crossing-new-horizons-vegan/

Schneider, T., Eli, K., Dolan, C., & Ulijaszek, S. (Eds.). (2018). Digital Food Activism (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315109930

Staiano A. E. 2014. Learning by Playing: Video Gaming in Education-A Cheat Sheet for Games for Health Designers. Games for health journal, 3(5), 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2014.0069

Taylor, Nicole and Mimi Nichter. 2022. A Filtered Life: Social Media on a College Campus. New York: Routledge.

Van Est, R., Rerimassie, V., van Keulen, I. & Dorren, G. 2014. Intimate technology: The battle for Our Body and Behaviour. Rathenau Instituut.

Veblen, Thorstein. 2007. The Theory of the Leisure Class. Oxford: Oxford UP.

White, Wajeana, Albert A. Barreda, and Stephanie Hein. (2019) “Gastrodiplomacy: Captivating a Global Audience Through Cultural Cuisine-A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Tourismology 5(2), 127-144.

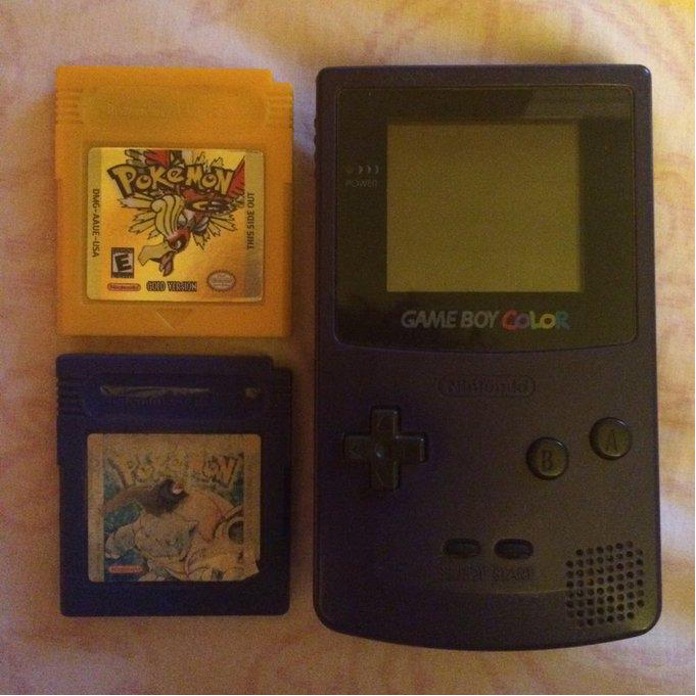

When I asked my aunt back in 2014 if my old Game Boy Color was still around, she handed it to me, but confirmed that the A and B buttons no longer worked properly. The Game Boy Color is a handheld game console that was released in 1998 as a successor to the black-and-white Game Boy (1989), though both consoles were discontinued in 2003. My grandmother had died recently, and we were clearing out my and my brother’s belongings from her newly empty house. Truthfully, I hadn’t touched this handheld console since the mid-2000s, around the time I upgraded from the family desktop computer to my own personal laptop. The title stickers on some of the cartridges had begun to wear out, but I held hope that this wasn’t an indicator of what their inside was like, or whether they had reached the end of their lives. I told my aunt I’d find a way to fix the buttons, to which she answered, “Why would you want to repair something from the past when the quality of what’s now in the present, on the market, is infinitely better?” In the mind of many people, it is indeed better to wait for a newer, more technologically advanced model to come out, a manifestation of planned obsolescence which we have learned to live with.

Photo by the author of a purple Game Boy Color with Pokémon Gold and Pokémon Blue cartridges.

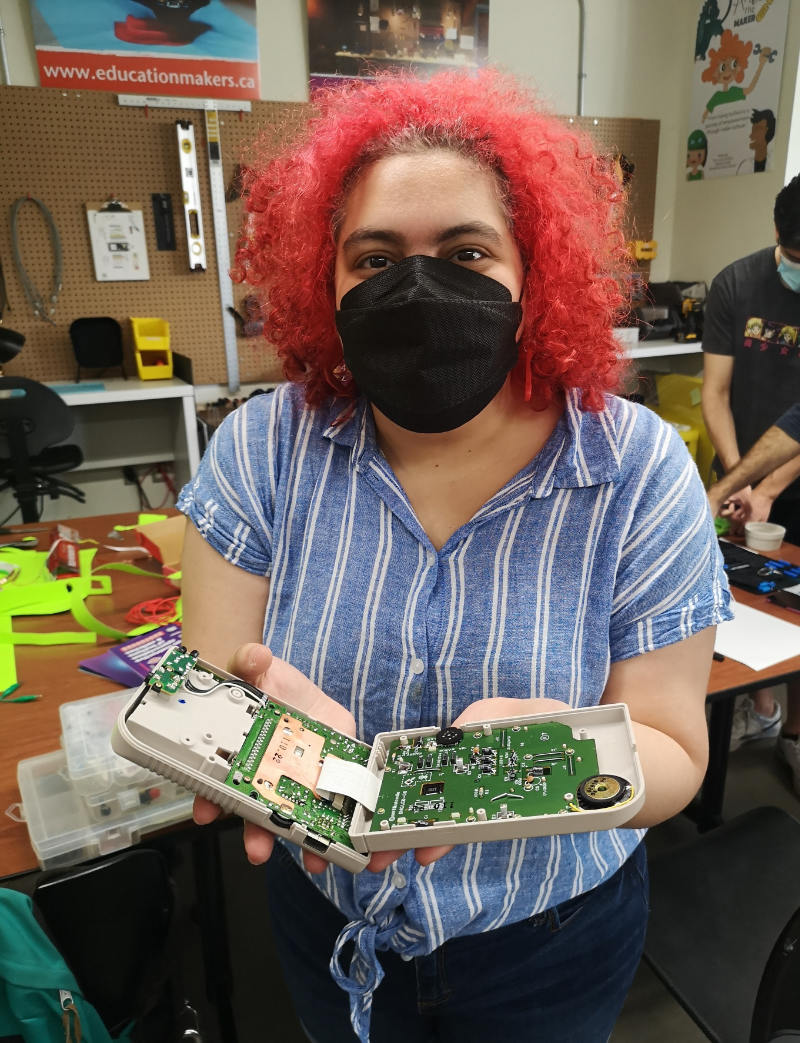

Flash forward to 2022, and I had still not managed to fix the buttons on my deep-purple handheld but I attended a Game Boy Hardware Hacking workshop hosted by Lee Wilkins, with the support of Alex Custodio and Michael Iantorno as part of a series of events leading up to a Solar Game (Boy) Jam. The purpose of this workshop was to hack into the console to alter the way it functions, involving changing the buttons. After a quick presentation, we started by removing the external screws from the Game Boy Color console using an “iFixit” toolkit. We had to use a tri-wing screwdriver because the screws Nintendo uses aren’t the typical Phillips; picture a peace sign Y, instead of a plus sign +. The internal screws were a plus sign (Phillips), however. The point of the screws requiring a different screwdriver is to stop you from getting in, but once you’re in, you’re in. We then took both sides of the case apart slowly, careful not to damage the screen or circuit board.

Photo by Yiou Wang of the author holding the Game Boy they had taken apart.

While concerned with sustainability throughout my whole life, ever since we had a tree-planting day at school when I was eight years old, my main takeaway from the workshop was not sustainability, but that I had been implicated in the process of making. I was made into an actor: not in the theatrical sense, but I had been given a role in making the game instead of just playing it. In other words, I became a “prosumer,” a mix between producer and consumer (Berg, Narayan, Rajala, 2021). I, and the workshop attendees, gained a form of agency that day through hardware hacking.

Taking the console apart felt cool, but we still had more to do. We wanted to hack into it and alter some of its functions, particularly the buttons, so the next step involved soldering. I had done some soldering before, with Alex and Michael as well, in May. We had replaced the volatile memory batteries on some Game Boy cartridges, which had to be soldered on the motherboard to stay in place. In the more recent workshop’s case, we soldered the exposed part of the wires onto the buttons and the wires served as extensions of the buttons which we could attach to conducting elements using alligator clips.

After everything was in place, we had to think about movements that would close the circuit on each button. We glued aluminium paper on cardboard to make bracelets, rings, headbands, and other accessories to connect to the alligator clips. Yiou, a visiting scholar, sketched out the positions we would be standing in. We stood in a circle to symbolise a circuit, with Alex holding the console in the middle of the circle. We each wore one or two of the accessories we had prepared earlier. The workshop attendees worked together: in order to move downwards, I would high-five Justin, Justin would (gently) smack Owen’s head to go left, and Richy and Yiou would elbow-bump to go right. Unfortunately, Tetris doesn’t have an upwards function so we couldn’t test Owen and Richy fist-bumping to go up. We modded a Game Boy console to become THE Game Boy console and played the coolest game of communal Tetris ever!

As I’m writing this, people are preparing for the eShop closure (the electronic Nintendo store through which people can purchase digital copies of games and other programs) on Nintendo 3DS and Wii U consoles by downloading everything they’d purchased before they no longer can, as per Nintendo’s official announcement. The 3Ds, successor of the DS (2004), was released in 2011 while the Wii U, successor of the Wii (2006), was released in 2012. People can still buy second-hand games for both platforms, in the form of physical cartridges, but as of this month (March 2023), they can no longer buy them digitally from Nintendo. This news came around the same time it was announced in Nintendo Direct that classic Game Boy and Game Boy Advance games will now be included in the Nintendo Switch Online membership, in digital form. Fans suspect DS and 3DS games will be next.

As defined by industrial designer Brooks Stevens in 1954, planned obsolescence is a marketing strategy that presumes that electronics are made with the intent that the consumer will want to discard them by the time their successor comes out on the market through “instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary” (Adamson and Gordon, 2003). Many people assume that with planned obsolescence, their electronics will break down immediately, or that their electronics will stop functioning. However, scholars suggest that consumers will be under the impression that their belongings stopped functioning because they don’t function the same way the latest model does (Miao, 2011; Kuppelwieser and Klaus and Mathiou and Boujena, 2019). In other words, it’s not really becoming out of use as much as it would become inconvenient to use them in conjunction with other existing, newer models on the market.

In a sense, getting into the console to fix a button or switch out the screen are sustainable efforts to combat planned obsolescence, all while giving consumers more agency over what they consume.

In Animal Crossing: New Horizons (2020), the game doesn’t end once the players reach the end credits. After the credits roll, one of the game’s NPCs, or non-player characters, tells the player that they’ve unlocked terraforming, making them an official “Island Designer” who can reshape hills, cliffs, create ponds, move bridges, to personalise their islands a step further than redecorating by putting down items from their pockets. Terraforming even comes with a white hard hat the player must wear every time they’re changing the architecture. This new feature that wasn’t included in previous iterations of the game before 2020 gives the player some form of agency, in my opinion, over what the game they’re playing looks like. In this case, agency was given, thus making it voluntary on the behalf of the development team and different from the agency consumers achieve through hacking and modding.

A form of agency I am more concerned with is people taking the reins of technology for themselves out of a want or a need. When I couldn’t get my Game Boy Color buttons to work in 2014—desperate to play Pokémon Crystal again—my first thought was to give up and purchase a 3DS, which would have newer editions of the game, though not the exact game I wanted to play. But I found a solution: Twitter friends opened my eyes to the world of emulators. To explain it simply, emulators tell a computing platform to operate a certain way that mimics another computing platform in order to run software that only works on a certain platform. Emulators exist for almost any platform and can even be encased in a shell that looks like one of the retro handheld consoles, another form of agency the players themselves have taken. I downloaded a Game Boy emulator onto my laptop and then downloaded a ROM file[1] of Pokémon Crystal that someone had modded to work on an emulator. I had so much fun playing it and reliving my memories, I ended up locking myself in my room for hours and hours every day that summer.

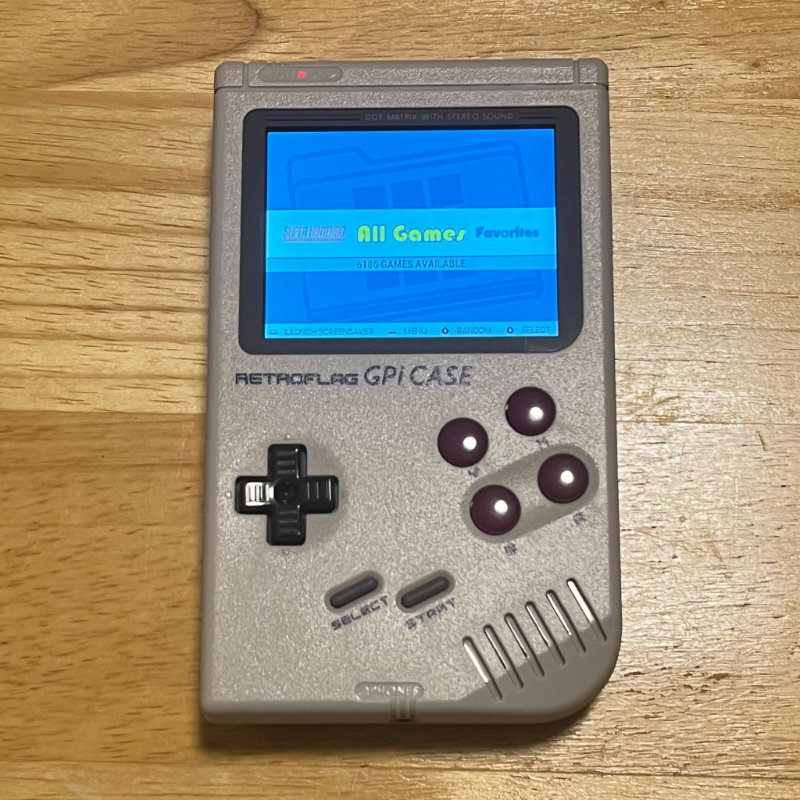

Photo by the author of the author’s Raspberry Pi computer encased in a shell made to look like a classic Game Boy.

As the technology advances, there will be more to consider in the process to stop defunct consoles from ending up in landfills. When it comes to software, emulators have proven to be the way to go to preserve the games. In the case of Nintendo closing down eShops for decade-old handheld consoles, it could be justified as the company choosing to focus their efforts on their current consoles over continuing to invest in supporting older platforms, which requires human labour and financial cost.

It can be quite scary to not know where to begin or which tools you need to repair or alter electronics, but all you need to do is to start tinkering. I will leave you with my now-functioning Game Boy Color buttons, taken apart, then replaced by my brother—who, just like me, has no background in any of this, but also has a lot of curiosity and doesn’t want to give up on our childhood memories.

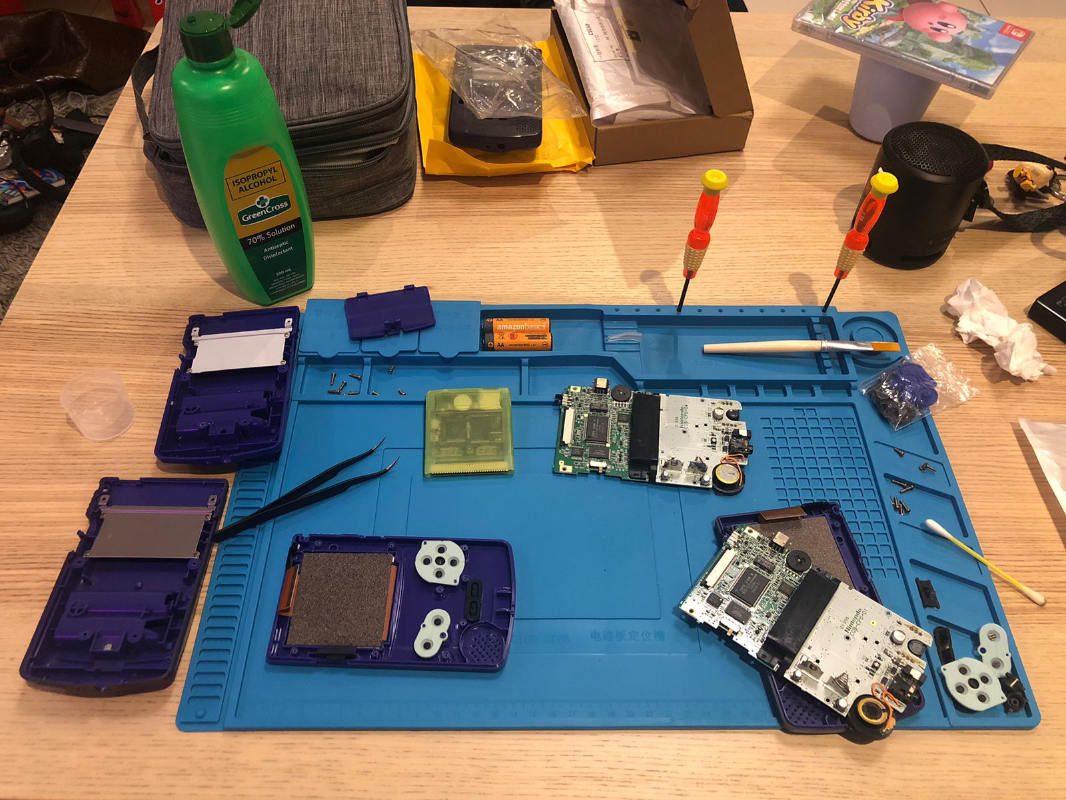

Photo by the author’s brother of a workshop area with tweezers, screwdrivers, rubbing alcohol.

[1]Read-Only Memory, the software data present on the game cartridges.

Adamson, G., Gordon, D. (2003) Industrial Strength Design: How Brooks Stevens Shaped Your World. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Berg, P., Narayan, R., Rajala, A. (2021) “Ideologies in Energy Transition: Community Discourses on Renewables.” Technology Innovation Management Review 11(7/8): 79-91.

Kuppelwieser, V., Klaus, P., Manthiou, A., Boujena, O. (2019) “Consumer responses to planned obsolescence.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 47: 157-165.

Miao, C. H. (2011) “Planned Obsolescence and Monopoly Undersupply.” Journal of Information Economics and Policy 23(1):51-58.