Amanda Holmes reads Nizar Qabbani’s poem “When I Love You,” translated by Lena Jayyusi and Jack Collum. Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “When I Love You” by Nizar Qabbani appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Adam Zagajewski’s poem “En Route,” translated by Clare Cavanagh. Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “En Route” by Adam Zagajewski appeared first on The American Scholar.

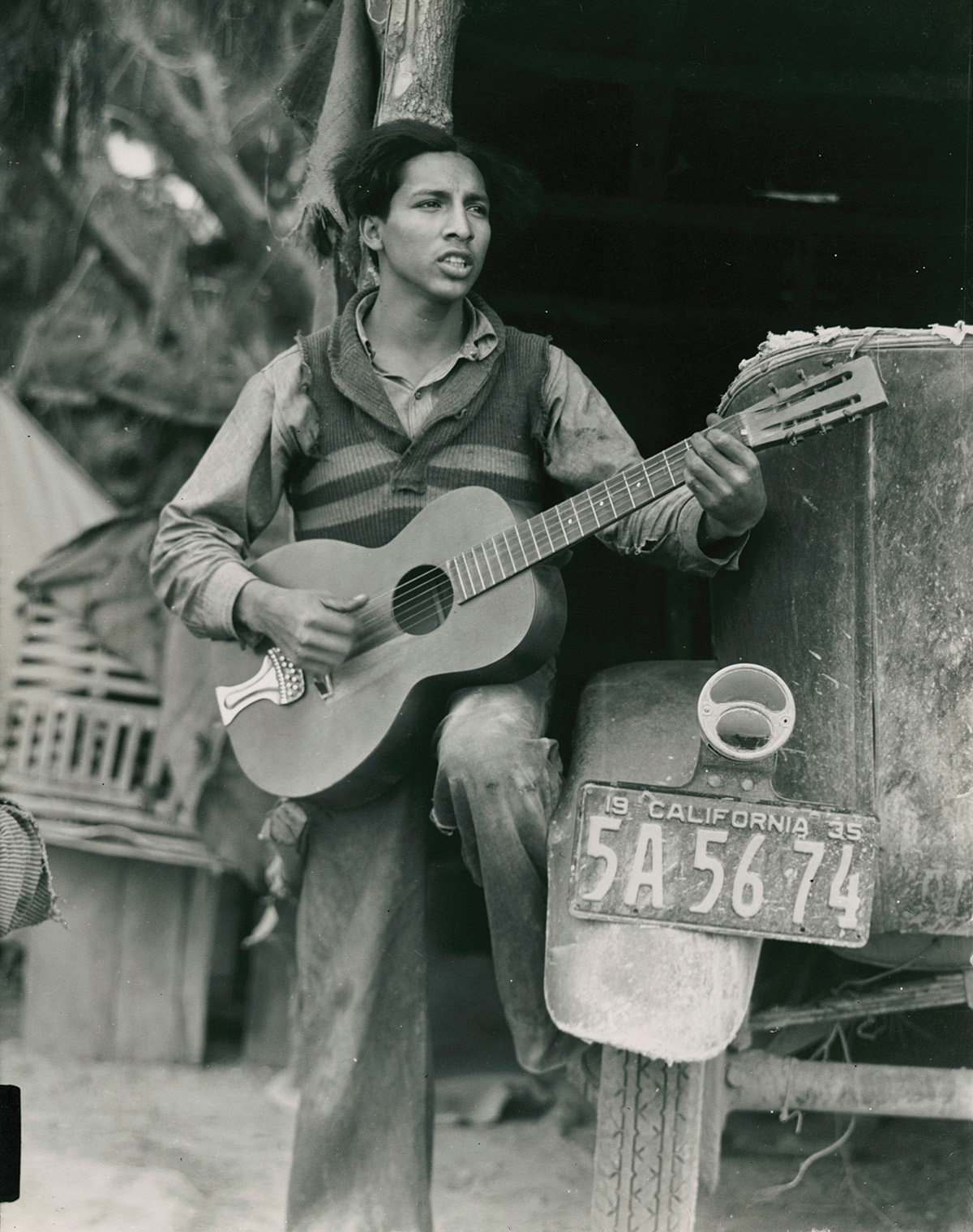

For American farmers, life changed dramatically in 1937. That year, electricity began flowing to hundreds of thousands of rural households, including some 12,000 in Wisconsin. The Rural Electrification Act (REA), which President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed into law the previous year, provided stimulus for utilities to install poles and wires where, until then, it hadn’t been economical to do so. Most farmers were thrilled. One who lived near Janesville, Wisconsin, said of the power company crew, “I thought sometimes that they weren’t ever goin’ to get here. The organizers told us we’d have juice by spring. But we finally did get it, and, by golly, I’m goin’ to shoot the works.” He showed a city reporter every electric light in his barn. His newspaper profile reads like REA propaganda, and it might have been. To persuade skeptical farmers—who were still feeling the effects of the Great Depression and balked at the prospect of a monthly electric bill—REA advocates mounted a forceful public relations campaign. Agents traveled across the country demonstrating electric appliances. Theaters presented a popular film, Power and the Land, which touted the benefits of electricity for agricultural operations and concluded with the line, “Things will be easier now.” Part of the campaign focused on convincing women. Electricity would give them lights, refrigerators, ovens, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and irons they could plug into an outlet. It would end their drudgery, the government promised.

But Jennie Harebo, a 64-year-old woman from central Wisconsin, wasn’t having it. After her town’s rural electric cooperative set eight poles and lines on her property, she sawed down one of the poles and parked her coupe on the downed wires. She stationed herself in the car, armed with a shotgun and a hoe. Newsmen called it a “sitdown strike,” a “vigil,” a “blockade.” Her husband, an “invalid,” brought her food. At dusk, she gathered blankets around her shoulders and lap and cradled the shotgun. One night, two nights, three nights she stayed. A sign on the windshield read, NOTICE: NO TRESPASSING. Harebo allowed no negotiating, entertained no tit-for-tat. Months earlier, she and her husband had won a case in the state’s supreme court that saved a riparian corner of their property from being seized by men who wanted to build a dam. The government’s lawyer must have suspected that his client’s case was doomed.

I imagine that Jennie Harebo, a woman of a certain age, was fed up with men’s impositions. Now they were trying to force lines through her vantage, light into her dark. Maybe she wanted to hold fast to twilight powers—the wonderment, the wisdom, the privileged views. Maybe she was simply cantankerous in the original sense of the word, which is rooted in the notion of “holding fast.”

What could she have seen in her three nights’ vigil? North Star, both dippers, crescent moon’s shine on the pump handle—the fixtures of haiku masters. Also, quotidian country lurkers and skulkers. Her night vision undefiled by electric shine, she surely saw scavenging raccoons, ambling possums, scuffling skunks. Maybe a lynx’s glassy gaze. She heard more, too, than her city relatives in their wired homes with their humming lights and fans and blathering radios. She could have made out the lawyer’s Pontiac approaching from a distance of 10 miles. She had plenty of time to aim her Remington out the driver’s side window.

Eighty years after Harebo’s stand, I took up wandering my rural Wisconsin property after nightfall. I longed for whatever sights diurnal living denied me. Trail cams mounted in the forest or by the creek had offered only glimpses: beavers adding branches to their dams, stock-still deer staring straight into the lens. The cameras, I was sure, didn’t reveal a fraction of the night’s secrets.

On clear nights, I stood under the Milky Way’s sprawling, splotchy canopy. I saw planets, constellations, comets, and once, a meteor afire and dying as it plummeted to Earth. The darkness of my rural township, an hour’s drive from the Harebos’ farm, was rare for modern times. In 2005, our town board passed a dark sky ordinance (whereas, whereas, whereas … and so, lights must be shielded, directed downward, calibrated, kept modest). Nevertheless, a yard light down the road, a sign at the corner bar, and the glow of a distant city interfered.

I sought deeper darkness. I found it at the nature preserve halfway between my place and the Harebos’ farm. One night, a self-made astronomer and his telescope met me and others at the preserve for a moonlit hike. Inside the visitors center, I discovered my friend Liz in the crowd, and we sat together. The occasion was a penumbral lunar eclipse. The astronomer began his program with canned, corny jokes. He introduced his two assistants, women who knew the trails and would guide us on the night hike. He must have mentioned the alignment of heavenly bodies, how Earth’s shadow would fall on February’s full moon, the snow moon, once it rose. But I’ve never retained stargazing facts. I’m slow to make out asterisms. I can’t recall which planets appear where and when or what temperaments the ancient Greeks assigned them. I merely love to bask under them.

We were all traipsing outside into the snow when, unexpectedly, the astronomer announced that hiking would be too dangerous because of ice. Instead, he would talk to us during the half hour before the moon rose. The group groaned, and Liz and I looked at each other. Like the astronomer’s assistants, we knew the preserve’s trails, at least the main ones. We backed away from the others and stole into the darkness.

We padded slowly and quietly over the glazed snow, keeping our eyes on the ground, gathering scant reflected light from unknown sources. The woodland trail was icy only on rocks or railroad ties. In those spots we braced ourselves and reached out to steady each other. Soon we joined the wider trail, formerly the old state highway. There, the snow was ridged from snowmobiles’ belts. As we walked on the crusted ridges, Liz told me about living in Dharamshala a few years earlier. I pictured her humid quarters in the mountains of northern India, the buildings’ bright colors, the Buddhist pilgrims surrounding her. I sensed the peace she had felt there and nowhere else. I shared her desire to return to Dharamshala, although I’d never been there. While visualizing that faraway place, I kept my eyes on my surroundings. Moving in the dark was a balancing art. I felt most adept when I looked out with a broad, allowing awareness, when I didn’t fix on fine details or make assumptions about the terrain. Liz and I arrived at the path’s apogee precisely when the clouds parted, the full moon rose orange, and as if cued by the shifting light, coyotes began howling.

What I have seen by the light of celestial bodies: rabbit prints as lavender shadows in the snow; bare, black elm branches waving; the red glow of varmints’ eyes at the compost heap; stars in puddles and brooks; my lover’s silhouette moving beside mine.

What I have not seen in the night and been surprised by: knee-deep muck; a snorting, thundering herd of deer; a frog on a door handle that I smashed under my palm as I hurried to get indoors during a rainstorm; a pickup truck without headlights barreling down the road—and the drunk young man at the wheel who, after nearly running me over, reversed and asked, “Are you okay? Geez, are you okay?” in a tone that told me his real question was, What are you doing walking out here after dark?

To be moon-eyed is to keep your eyes wide open and to be awed. But to be moony is to be absent-minded, loony, or at least naïve. With better night vision, I thought, I could steer my life toward more moon-eyed moments than moony ones. Maybe I could take in more good surprises than bad and live with heightened awareness, less delusion. Seeing what I’d been missing all along might grant me new, original insights.

Humans are born with the ability to see in low light. But compared with that of other animals, our night vision is feeble. We lack the nocturnals’ giant pupils (think doe-eyed ) and their tapetum lucidum, a structure at the back of the eyeball that acts as a mirror, amplifying starlight into floodlight and reflecting it back onto the retina. Our natural night vision can be eased into—it takes a while for our sight to adjust to dimness—but in general, it can’t be enhanced. Using lubricating eye drops or eating more beta carotene, for most well-nourished Americans, won’t improve it. Other habits, such as staring at computer screens or the sun, can degrade it. Unfortunately for Harebo and me and others past their physical prime, night vision also diminishes with age.

To compensate for human deficiencies, engineers developed night vision goggles during World War II. Now every optics store sells them. Some years ago, craving a clear view of the outdoors after sunset, I bought a pair. I stood on our deck, held the goggles to my face, and scanned the horizon. Deer in the field glowed an unnatural phosphor green. Nothing more. No portal opened to a secret world. No mysteries were revealed. In the years following my purchase, I rarely picked up the goggles when I set out in the dark. What I really wanted was something innate and unencumbered, a better version of what I was born with.

Scientists have researched ways of improving human night vision. A chlorophyll derivative called chlorin e6 has shown promise in mice. In 2015, Gabriel Licina and Jeffrey Tibbets, self-styled biohackers with a group called Science for the Masses, gained notoriety for trying the substance. A solution of chlorin e6 was dropped into Licina’s eyes. Two hours later, he and others, acting as controls, were taken to a place where “trees and brush were used for ‘blending’ ”—presumably, an attempt to create a uniform backdrop for all participants. Licina and the control subjects were asked to identify letters, numbers, and other symbols on signs. The experiment appeared to have been successful. Controls correctly identified the objects a third of the time, while Licina did so 100 percent of the time. Afterward, he acknowledged to a journalist that the experiment was “kind of crap science.” Without knowing the potentially harmful effects of chlorin e6, the biohacker had been willing to risk his everyday vision for the possibility of gaining night vision, if only for a few hours (the drops’ effects wore off by sunrise). But Science for the Masses lacked sufficient funding to conduct the sort of extensive, ethical trials that more esteemed researchers require.

In photographs from that night, Licina stares at the camera like some mad alien, his eyes watery and opaque with their larger-than-life black irises—a consequence not of the chlorin e6 but of the oversize light-dimming contact lenses he wore. His creepy appearance and the report’s description of him roving in a dark wood made me think that the young men had especially enjoyed the homemade horror-film aspect of their experiment. Maybe they lusted after superpowers that would allow them to recognize and slay the dark’s monsters. After all, night vision is one superhuman capability that’s nearly achievable. Unlike time travel or leaping tall buildings, it’s only just beyond our grasp.

“Darkness, pitch black and impenetrable, was the realm of the hobgoblin, the sprite, the will-o’-the-wisp, the boggle, the kelpie, the boggart and the troll. Witches, obviously, were ‘abroad,’ ” journalist Jon Henley wrote of life before artificial lighting in a 2009 article in The Guardian. Real monsters coexisted with the fantastical. In the London, Munich, and Paris of the early 19th century, thieves, rapists, and murderous gangs roamed freely. According to Roger Ekirch, author of At Day’s Close, humans were never more afraid of the night than in the era just before gaslights illuminated the cities’ streets. Murder rates then were five to 10 times higher than they are today. And yet, Erkich adds, “large numbers of people came up for air when the sun went down. It afforded them the privacy they did not have during the day. They could no longer be overseen by their superiors.”

Darkness made equals of poor and wealthy, servants and masters, women and men. Past sunset, oppressors needed artificial light to point out their symbols of country and religion, to run factories and enforce conforming behaviors. For the less powerful, darkness and the ability to navigate celestially meant freedom.

Jennie Harebo’s vigil attracted reporters and photographers from across the state, their cars lining the roads near her farm. The visitors, she said, treated her courteously. A deputy sheriff persuaded her to put down the shotgun. And the REA’s lawyer finally relented, having decided to circumvent the Harebo farm after neighbors agreed to accept the poles and lines on their properties. The utility paid Harebo $25 for her trouble and removed the eight poles that it had installed on her land. “With nothing left to fight for,” a newsman wrote, Harebo ended her vigil after about 96 hours. “Storing her formidable hoe in the woodshed, [she] claimed victory today.” She abandoned her coupe, “her husky frame sagging a little with weariness.” The crowd that had gathered to watch the three-day standoff dispersed. “Ultimately,” another reporter mocked, the family’s “need for kerosene lamps continued.”

In opposing electricity, Harebo was a rare exception. Some farmers didn’t even wait for the REA. Two decades before her blockade, men who once lived along the road between my home and the nature preserve were so eager to have electricity that they collected their own poles and wire. They used tractors, shovels, and muscle to run lines from the nearest village. Theirs was the nation’s first farmer-led electrical cooperative. It functioned independently for 20 years, disbanding only in the early 1930s, when the state butted in and began interfering in its operations.

Although she opposed lines on her own property, I imagined that Harebo would have admired the farmers’ refusal to comply with state regulations. As one farmer remarked on the public service commission’s successful attempt to set his cooperative’s prices, it “was a good example of the chair-bottom warmers’ insatiable desire to run everything.” In the years since I learned about Harebo’s vigil, she’d become a minor heroine in my eyes. Here was a tough woman who had fended off the establishment. She had battled for her rights—to the darkness and the freedoms it brought her, to the preservation of her night vision—even if she was weary and sagging.

Standing on the groomed snowmobile route, Liz and I watched the full moon fade to yellow and shrink behind clouds. Then we left for the narrow forest trail. We picked over rocks and logs and a trickling, perennial creek. Farther on, we listened to our breathing and footfalls, nothing more. We found the meadow next to the parking lot of the visitors center. Ahead, clustered around the telescope, stood the astronomer and part of the group we’d started with.

The clouds disappeared again. I looked up to watch the space station dash a diagonal across the sky. The astronomer invited me to view the moon in the telescope. “Lean into the eyepiece,” he told me. “Don’t touch anything.”

Singled out in close-up, the moon nearly blinded me. The penumbral eclipse, a subtle shading on the moon’s surface, was too faint for me to detect. I kept my eye to the telescope only long enough to assure the astronomer that I’d made an effort. I didn’t like the way the instrument isolated the moon. Without its complement of stars and planets, it was a flattened, vapid object. I felt as if I were ogling it but not really seeing it.

Liz took a brief turn at the eyepiece, too. Then we walked to our cars, agreeing to meet again for more nighttime hikes.

People soon will be able to choose better night vision like they can choose to eliminate forehead wrinkles. Professional scientists—not only biohackers—are working on it. In 2019, Gang Han and his fellow researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School announced that they had enabled mice to detect near-infrared light by injecting nanoparticles into their eyes. After the injection, the mice could see phosphor-green shapes in the dark, as if they were wearing night vision goggles.

Not surprisingly, safety and security, national or personal, are often cited as reasons for such research and its funding. What if soldiers, for example, could see enemies after dark without the hassle and weight of equipment? In one article, Han suggested testing the eye-injected nanoparticles on dogs next. “If we had a ‘super-dog’ that could see NIR [near-infrared] light,” he told a reporter, “we could project a pattern onto a lawbreaker’s body from a distance, and the dog could catch them without disturbing other people.” As if criminals wouldn’t dodge behind obstacles; as if police with their natural night vision could make out the perpetrators well enough to project shapes onto them; as if dogs wouldn’t be distracted by all the marvels their new night vision revealed and dash away from their handlers.

The delivery method—an injection into the eye—also makes this night vision technique impractical. Recently, though, when I spoke with Han, he told me that his lab might soon begin testing a wearable device, such as a patch or contact lens, on humans. He imagined an application in which a security agent wearing a night vision patch could see details in facial recognition software that others could not. But for this, more funding would be required. Of the lab’s many projects, night vision research has received the most attention in the media. But not from industry or government. People at the big granting agencies, such as the National Science Foundation or National Institutes of Health, Han told me, “can’t recognize its importance in daily life.”

Months after fixing Jennie Harebo’s image in my mind, I found an article about her that I hadn’t seen before. It included a photograph, likely taken after she ended her vigil. She looked nothing like the newsmen’s descriptions. Although the image was dim from age and poor scanning, I could tell that her hair was curled and styled. She wore a buttoned-up overcoat with a contrasting collar, maybe fur. She struck a movie star’s pose beside the coupe—jaw set, chin lifted, face turned slightly, gaze fixed on the middle distance. She was beautiful. Her frame was upright, not sagging. She showed no sign of weariness after 96 hours in the car. Shotgun held at her side, she looked ecstatic and carefree. Seeing the photograph chastened me. I had allowed the newsmen’s descriptions of Harebo to deceive me. I’d been willing to accept that she was crabby and exhausted from her ordeal. But the word vigil, after all, is rooted in “lively” and “strong.” Maybe she didn’t consider it an ordeal at all. Maybe she relished the standoff.

Harebo’s proud posture reminded me of when I lived in Lansing, Michigan, during college and joined friends to march down the middle of the street. We held posters or candles and shouted, “Women unite, take back the night!” We claimed our right to be safe from monsters in the dark—symbolically, of course. The real, human perpetrators were always about, day or night, visible or not. Who knows if our stand changed any policies. But it changed me. Marching to reclaim the dark brought me a sense of solidarity among women that school, work, and family had not. Even so, I thought as I studied Harebo’s photograph, my efforts hadn’t gone far enough. I hadn’t fully imagined what we would do with our freedom after we won the night.

During the summer after our first moonlit hike, Liz and I took more late-night excursions to the middle of nowhere. What I saw with my natural, flawed night vision: shooting stars, swooping bats, slumbering farm machinery, and the lift and dip of a rare, blue-glowing firefly. What I felt, as I listened and shared more stories with my friend: a keener attunement, an ease among shadows, and the assurance of being fully seen—so much of what daylight’s glare had been hiding.

The post Night Vision appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Maxine Kumin’s poem “Morning Swim.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Morning Swim” by Maxine Kumin appeared first on The American Scholar.

The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy, and the Wild Life of an American Commune by Alexander Stille; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 432 pp., $30

It’s almost amazing that not once in his intensely readable new book does Alexander Stille quote Philip Larkin’s most (in)famous line of poetry: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.” That sentiment was, essentially, the motivating principle of the communal Sullivan Institute, a rogue psychotherapy outfit on Manhattan’s Upper West Side that—over the course of its more than 30-year existence, from the late 1950s to the early 1990s—grew into a sex cult committed to abolishing within its midst the nuclear family, on the grounds that close romantic and familial bonds were psychologically harmful to adults and children alike.

But Stille has equally pungent material to work with. One Sullivanian is quoted saying of his own forebear, “It’s easy to be an anti-Semite when you grow up with a father like that.” Another’s mother is referred to as “that old womb with a built-in tomb.” The latter quotation comes from painter Jackson Pollock, who’s among a small parade of notables who wander like oddballs through this strange milieu. (Others include art critic Clement Greenberg, singer Judy Collins, and novelist Richard Price.)

Dishy as it is, however, Stille’s book is hardly an exercise in name dropping. The true heroes and villains in this story—most individuals, children excepted, take turns being both—are everyday people whose dramas are sometimes darkly amusing but more often heartbreaking. These are real members of nontheoretical families who found themselves at once the victims and willing enforcers of disastrous social theories that were explicitly, vilely antifamily. Through all phases of the story, from the kinky, free-love eccentricity of the early years to the insularity, paranoia, and criminality of the later years, Stille maintains an admirable, almost tenacious sympathy for his subjects—a sympathy some of those subjects, in retrospect, aren’t sure they deserve. But as the cognitive dissonance grows, so too does the tension, making the book an improbable thriller, propelling us from chapter to chapter to see how these unfortunates will extricate themselves (if they can) from a Gordian knot of their own creation. Will anyone make it out emotionally intact, reasonably functional? Will they be reunited with their own blood, whom they’ve been conditioned to regard with indifference if not hostility?

One cavil: Stille places the origin of his story in a typically caricatured version of 1950s America, an unsophisticated place marked by little more than stifling convention (Father Knows Best, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet), but with a hint of rebellion on the horizon (Rebel Without a Cause, On the Road ). The implication being that the Sullivan Institute was part of that incipient rebellion, a harbinger of the revolutions to come in the ensuing decade. This is misleading on two fronts.

First, 1950s America was not some sheltered national virgin whose inaugural orgasm awaited in the mind-blowing, consciousness-raising ’60s. The conventionality we associate with the ’50s was partly a return to normal after the 1940s, a decade that—owing to war-related domestic upheavals—saw myriad social and sexual pathologies rise, some drastically. (Jack Kerouac’s dionysian On the Road, it should be remembered, was a chronicle of journeys taken mostly in the late ’40s, though the book wasn’t published for another decade.) Given this recent anomie, the return to conventionality in the 1950s was akin to what Stille observed among former Sullivanians, who left behind the commune’s deliberate parental chaos and loveless promiscuity to find shelter in the old-fashioned romantic and family structures the commune had forbidden.

Second, the ideas that animated the Sullivan Institute weren’t born in reaction to 1950s American convention. They were a proactive (if kooky) extension of theories that had emerged partly from the Frankfurt School in the prewar years. One of the Sullivan Institute’s founders claimed to have learned at the feet of, among others, the social psychologist Erich Fromm, who himself had participated with a Frankfurt School colleague, philosopher Max Horkheimer, on Studies on Authority and the Family (1936). That publication is a heady mix of Freudianism and Marxism that placed the family—its dynamics, dysfunctions, sublimations, and pathologies—firmly within a web of larger social and historical forces that acted on it. Those forces chiefly related to capitalism, under which fathers were seen to enact a kind of small-scale ownership and exploitation of their own families. If the surrounding society could be made more just and egalitarian, it might, in Horkheimer’s words, “replace the individualistic motive as the dominant bond in relationships,” giving rise to “a new community of spouses and children,” in which children “will not be raised as future heirs and will therefore not be regarded, in the old way, as ‘one’s own.’ ”

That’s a pretty fair approximation of what the Sullivanians fancied themselves pursuing. How did it go? “There was a feeling of pressure,” said one cult member, “that was really unpleasant, of having to conform in a certain way to unconformity.” Women endeavoring to get pregnant were required to sleep with multiple men while ovulating, to obscure paternity, which—said one male Sullivanian remorsefully—made it “easier to dissociate from the possible offspring.” Maternal bonds were broken as well, as children were taken from their mothers and raised in other parts of the commune by groups of men or women, with biological mothers being granted ruthlessly limited interactions with their offspring—and those offspring ultimately being denied knowledge of their origins. Per Horkheimer, children were not, in the old way, one’s own. Many of the children themselves came to regard their parents as “insane,” “basically a bunch of zombies.” In the long aftermath, one remarked, “I’ve thought three different men were my father in the past three years. I’m exhausted by having to relive the mistakes of my parents.” Another felt that he had been treated like an “experimental subject”—his childhood and his tender, developing psyche deformed by others’ commitment to validating a theory.

The Sullivan Institute insisted that every family—categorically—was a source of Larkinesque psychological damage. Then the institute became a scaled-up version of one and proved it.

The post Family Tatters appeared first on The American Scholar.

I got the call late on a summer afternoon. Yanai Segal, an artist I’ve known for years, asked me whether I’d heard of the Salvator Mundi—the painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that was lost for more than two centuries before resurfacing in New Orleans in 2005. I told him that I’d heard something of the story but that I didn’t remember the details. He had recently undertaken a project related to the painting, he said, and wanted to tell me about it. I was eager to hear more, but first I needed to remind myself of the basic facts. We agreed to speak again soon.

As I refreshed my memory in the following days, I learned that although there was considerable controversy about the history and legitimacy of the painting, there was some general consensus, too. The Salvator Mundi—“Savior of the World”—was most likely completed at the turn of the 16th century. An oil painting rendered on a walnut panel, it depicts Jesus offering a blessing with his right hand while holding an orb that represents Earth with his left. Studies made in preparation for the painting had been authenticated as genuine Leonardos, and at least 30 copies were believed to have been produced by Leonardo’s disciples directly from the original. Records show that the painting was in the collections of various British aristocrats and royals, including King Charles I, but sometime at the end of the 18th century, it effectively disappeared. When the work turned up at a New Orleans estate sale in 2005—heavily damaged, poorly restored, and painted over in several places—two veteran art dealers, Robert Simon and Alexander Parish, thought it might be significant and purchased it for around $10,000. They hired Dianne Modestini, a scholar and master art restorer, to clear away the restorations and repairs that the painting had undergone over the centuries to produce a definitive version. What emerged was an artwork that some experts believed to be the genuine Salvator Mundi. Others were not convinced.

Beginning in November 2011, the restored painting was displayed as part of a large exhibition of Leonardo’s works at London’s National Gallery, which had authenticated the painting. In 2013, it sold for about $80 million in a brokered deal that saw it resold the following day for $127.5 million. In 2017, it went up for auction again, this time selling for more than $450 million—the highest price ever paid for a work of art—to an unknown bidder who turned out to be a Saudi prince reportedly acting as a proxy for Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman. The work was supposed to be part of a landmark 2019 exhibition at the Louvre commemorating the 500th death anniversary of Leonardo, but the painting never went on display, the reasons for its exclusion never made public. And though scientific examinations done by the museum had confirmed that the painting was genuine (at least according to a secret book prepared, but never published, by the Louvre), questions about its authenticity have lingered. The entire saga of the painting’s travails through the contemporary worlds of art, wealth, and politics was traced in the 2021 documentary The Lost Leonardo, which portrayed how the superrich are able to hide their wealth in the form of high-end art.

I was surprised that so many discussions of the painting had focused more on these financial aspects, and the controversial nature of how it changed hands, than they did on aesthetics. To me, the bigger question was whether this artwork had the effect of a Leonardo. And when I looked at an image of the restored painting, I could not be sure. I saw a hint of the master before me, but something seemed to be missing.

I was curious about the kind of project Yanai had undertaken. His efforts lay mainly in the realm of contemporary art, which he usually exhibited in large-scale installations. He had studied academic drawing as a teenager and then visual art at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. He was a founding member and curator of the Barbur Gallery, a collective art space that has hosted both local and international artists since 2005, and has worked as an illustrator and a designer, creating everything from animated videos to children’s books. His studio, which I’d visited regularly over the years, was full of large-scale abstract paintings and conceptual sculptures made of such materials as hand-mixed concrete and Styrofoam. But there were often small oil paintings, too, scattered around, many of them still lifes of flowers. For as long as I’ve known him, Yanai has investigated the tension between figurative and abstract art, combining 20th-century modernist patterns with a contemporary aesthetic language. I had never known him to take an interest in the work of the Old Masters.

When I asked Yanai about his project, he told me that he had come across two images of the Salvator Mundi—the restored version that the world had come to know and an earlier, damaged iteration, with many of the original artist’s brushstrokes still visible. Wondering if a digital restoration would yield a different result, he decided to draw on his many years of computer experience and attempt to restore the painting himself. He had accomplished a great deal, he said, and though he wasn’t yet done, he sensed that his work might provide a clearer view of the artist’s original vision.

When I saw a photo of the damaged Salvator Mundi, I had an immediate idea of what had inspired Yanai. Looking at the half-tattered canvas, with the figure of Jesus bearing a haunting expression, I experienced an emotional reaction that had been absent when I’d seen an image of the physically restored version. Although I was not sure whether a digital restoration could be called legitimate, I was curious whether the emotion of the original—which, to me, was missing in the physical restoration—could be better captured using digital means. If so, it would raise a whole new set of questions about the painting and its authorship. When Yanai invited me to his studio in Tel Aviv to see the work in progress, I told him that I’d be there in a couple of days.

The Salvator Mundi in its damaged state—cleaned but not yet restored (Wikimedia Commons)

I got on the train from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv on a hot July afternoon. When I arrived at Yanai’s studio, he made me a cup of strong black coffee, sat me down in a chair, and opened up a laptop, revealing an image of a half-restored Salvator Mundi. This was nothing like the painting that was famous the world over. This one had more gravitas, more power. It had the kind of arresting presence I associated with Leonardo.

Yanai began to explain to me how he had performed his restoration. With extremely close-up zooms into a photograph of the damaged original, he was able to pick up pixel-resolution pigment traces adjacent to the damaged areas. Whereas a typical art restorer would, at this point, add new pigments to the painting, Yanai used digital impressions of the surviving work to fill in the missing sections. He looked at images of every known copy of the Salvator Mundi to determine what might have been on the original walnut panel. He constantly zoomed in and out, looking at the overall image, then going back in to fill in the pixels, watching as, step by step, a new version of the painting emerged.

I thought Yanai had a powerful image on his hands, and I asked him to tell me more about how the project came into being. He shrugged and said it was sort of by accident. During the pandemic, he began listening to podcasts while working on illustrations and book covers. One of those podcasts was about the Salvator Mundi. Intrigued, he searched for the painting online and came upon the image of the damaged work. It moved him. It was totally ruined, he said, but really like gazing at a figure behind a beaded curtain. If he could just reach out and move the curtain, he said, he could see what lay behind. He’d never attempted anything like a digital restoration of a painting, but the idea stayed with him. It wouldn’t leave him alone.

Yanai did a preliminary test, and the result turned out better than he’d imagined. It didn’t look like an artwork yet, but slowly he could see a new version of the painting appearing on the screen. As I looked at the image he had created, something about it tapped into a deep emotional well in me. Sure, the physical restoration had been historically researched. It had material integrity, dutifully bringing back to an optimal state a painting that had been badly damaged and inexpertly conserved over the centuries. I also understood that the motivation of the restorer was different: to preserve a physical object that could later be sold at auction. But for me, that object lacked feeling. And no matter how many times it was—or wasn’t—attributed to Leonardo, it could never be a legitimate Leonardo if it didn’t also have emotional force. It could be a Leonardo painting, but not a Leonardo artwork.

Yanai was heartened by my response, but he was still concerned about the significance of his undertaking—in particular, how it related to the ongoing debate about the physically restored painting. He was also wary of the fine line between the project of re-creating an image by Leonardo and the possibility of its being seen as an artwork of his own. He was not invested, he said, in creating a Yanai original. He was pursuing a vision that squarely belonged to Leonardo. But he couldn’t totally take himself out of the equation, either. Which left him with a lot of questions.

Still, he said, the project had become a compulsion. He’d sit down to create an illustration or design a book cover, feel compelled to take a quick look at the Leonardo, and then end up working on the restoration for hours. His initial aim had been to fill in the missing sections using information gleaned from the damaged original. Once he took this as far as it would go, however, he saw that some areas lacked sufficient data for him to finish the painting using simple digital deduction. In those sections, he explained, he had to think like an artist and re-create the missing areas in accordance with what he believed Leonardo might have intended. He was no longer fixing a painting, he said, but working on an interpolation. It was hard to move into this space, and that was why he’d stopped. He was looking to get some perspective on the project as it stood.

Yanai asked what I thought about his restored version so far. I told him the truth. That I didn’t quite know yet what to make of it, and that I needed to think some more. Since he was only half done, it was hard to make any final judgment. All I could say was that his version felt closer to what might have been the original. We agreed that I’d return once he’d worked on it some more. And I repeated that the main issue, for me, was the emotional element—there was something uncanny about the damaged painting that was missing from the physical restoration, something that seemed better preserved in Yanai’s image.

The Salvator Mundi after the restoration performed by Dianne Modestini. Although experts at the Louvre authenticated the restoration as a genuine Leonardo, questions about its authenticity remain. (Wikimedia Commons)

On the train ride home, I began to reflect on some questions that had been on my mind since Yanai first told me about his project—for reasons that had nothing to do with him or the Salvator Mundi. A decade earlier, during a trip to Paris, I had met a retired-businessman-turned-philosopher named Hervé Le Baut. I had been seeking information on the life of the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, one of France’s foremost philosophers in the period after World War II. Merleau-Ponty had been a close friend and colleague of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who all together founded Le Temps modernes, one of the best-known postwar journals. In the early 1950s, not long after Albert Camus’s falling-out with Sartre over their political differences, Merleau-Ponty also cut ties with Sartre. Researching any direct links between Camus and Merleau-Ponty, I had sought out Le Baut, who had written a book on the French philosopher. When we met at his home, Le Baut said he knew little of Merleau-Ponty’s connection with Camus, but he then revealed to me something that was common knowledge to people with an interest in Beauvoir but was mostly unknown to everyone else. It was a story of legitimacy.

The story appears in Beauvoir’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958), in which she describes the death, nearly 30 years before, of her beloved friend Zaza, who, she reports, died after being spurned by a man named in the book as Jean Pradelle. In reality, this man was Merleau-Ponty. What Beauvoir didn’t know—and what she learned from Zaza’s sister only after her memoir was published—was that Merleau-Ponty had turned Zaza away for the simple reason that her parents, who’d hired a detective to look into his family’s past, had discovered that he was an illegitimate child. They told him to either halt his pursuit of Zaza or be publicly exposed. And so he ended the relationship. Zaza died not long after the breakup. Zaza’s sister supposedly showed Beauvoir letters suggesting that Zaza herself knew of the whole debacle—that the tragedy had indeed been fatal to her, killing her first in spirit and then in body.

Merleau-Ponty would have been 21 when this took place and seemingly hadn’t known of his own illegitimacy before it was revealed to him by Zaza’s family. It’s chilling to think of how he learned of his provenance, from people who were hardly more than strangers, crushing not only his love for his fiancée and his plans for the future but also his entire understanding of his own past. The moment was powerful and deeply traumatic, and perhaps that’s why, years later, sitting down to write an essay on Paul Cézanne, Merleau-Ponty found himself veering into the personal history of Leonardo—one of the most famous illegitimate children of all time.

As soon as I got home, I reread “Cézanne’s Doubt.” Merleau-Ponty first raises the matter of Leonardo’s illegitimacy as part of an argument about the relationship between childhood and adulthood—between the powerful feeling that our lives are determined by our births and the similarly powerful feeling that we can determine our future by our actions. And though the argument is first built on Cézanne, Merleau-Ponty makes a sudden pivot, referencing Sigmund Freud’s book on Leonardo and refocusing his discussion on one of the only times Leonardo ever mentioned his childhood: when he described the memory of a vulture coming to him in the cradle and striking him on the mouth with its tail. With this sleight of hand, Merleau-Ponty turns an essay ostensibly about the role of doubt in creativity into a meditation on origins—in this case, the origins of arguably the greatest master of all time.

Continuing to lean on Freud, Merleau-Ponty reminds us that Leonardo “was the illegitimate son of a rich notary who married the noble Donna Albiera the very year Leonardo was born. Having no children by her, he took Leonardo into his home when the boy was five”—the same age when Merleau-Ponty experienced the death of the man he thought was his father. Merleau-Ponty then adds, in a tone that takes on a subtle lyricism, that Leonardo “was a child without a father” and that “he got to know the world in the sole company of that unhappy mother who seemed to have miraculously created him.”

Those lines changed how I read Merleau-Ponty’s essay. When he writes about Leonardo’s “basic attachment” to his mother, “which he had to give up when he was recalled to his father’s home, and into which he had poured all his resources of love and all his power of abandon,” I imagined Merleau-Ponty refracting his own attachment to his mother through the Renaissance artist. When he later writes that Leonardo’s “spirit of investigation was a way for him to escape from life, as if he had invested all his power of assent in the first years of his life and had remained true to his childhood right to the end,” Merleau-Ponty seems to be mirroring his own sense of curiosity and wonder as a thinker. Elsewhere, when he writes that Leonardo “paid no heed to authority and trusted only nature and his own judgment in matters of knowledge,” I couldn’t help but think of Merleau-Ponty reflecting on his own moment of truth—when he discovered his illegitimate origins and, still young and insecure, succumbed to the social pressures exerted on him. He is writing about Leonardo, but he could well be writing about himself.

I was curious about the source of Merleau-Ponty’s ideas on Leonardo, so I turned to Freud’s Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood. “In the first three or four years of life,” writes Freud, “impressions are fixed and modes of reactions are formed towards the outer world which can never be robbed of their importance by any later experiences.” The impression that Leonardo would have had of himself as a fatherless child would have likely haunted him throughout his life. And, it occurred to me all at once, his circumstances would also have helped him identify with the most famous of “fatherless” boys—Jesus.

And that’s when it all came together. What better way to create an everlasting emblem of your most consequential childhood impression than to paint yourself as the Salvator Mundi—the savior of the world? What could be more audacious than to turn your illegitimacy into one of the most powerful religious symbols ever created?

It wasn’t a totally wild idea. Lillian Schwartz, a visual artist working with digital media since the 1960s, had made a claim back in 1987 that the Mona Lisa was a self-portrait of Leonardo. But it was one thing to turn yourself into a woman, and quite another to paint Christ in your own image. It took Leonardo’s penchant for games and riddles into the realm of blasphemy. Yet on another level, it was also a simple and perfect way to expose something about yourself that was otherwise difficult to address—to get an emotion across without having to identify the emotion itself. Merleau-Ponty, writing about Leonardo, had done the same thing. He had told his personal story through a figure so grand that no one had ever guessed he might have been talking about himself. He had done to Leonardo what Leonardo had done to Jesus.

I was tempted to call up Yanai and tell him about my hypothesis. But I realized that he first had to complete his image without knowing of my thought experiment. Then, once it was done, I could put his Salvator Mundi next to other portraits of Leonardo—and compare.

Yanai Segal’s digital restoration of the painting believed to be Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi (Yanai Segal)

Six months passed. It was a busy time—a new coronavirus variant was rampant, and obligations ballooned. I seemed unable to catch up with anything. By the time I talked to Yanai about his project again, he told me that he had gone as far as he could with the image. Finally, in early winter, I found a moment to visit him again at his studio. As we settled into our chairs and he reached for his laptop, I sensed that I was sitting next to a changed person. He hadn’t just stopped work on the digital restoration. He’d come to some sort of understanding.

Yanai opened his laptop and revealed the image. I was struck by how final it looked. I still had the damaged painting in mind, with its haunting rips and scratches, and it was somewhat jarring to see the apparent magic trick that Yanai had performed—as if he’d resurrected the original image. The digital process he’d used had evolved during those months. At some point, he thought he had finished, but the image had looked too smooth, too new, lacking any of the mystique or allure of a 500-year-old painting. The damaged work, he said, gives you a mental image that’s difficult to unsee. It has a kind of fuzziness, a softness around the eyes and face, from all of the scratches and erasures. He realized that to restore the image properly, he also had to preserve the damage it had suffered over the centuries. So he removed the most recent layer altogether and started putting the painting back piece by piece. Many of the sections he thought he’d “fixed,” he said, had turned from interpolations into interpretations, so that, slowly, the painting had also become his, which had never been his intention. Having fully restored the image, he began scaling back his work—but this time with the knowledge and experience of having examined every single pixel and pigment. He stopped “fixing” the painting and started reclaiming the parts that were lost. And as he did, he discovered that the sections that looked “lost” were not lost at all. They just needed a little push to make them more clearly visible.

I asked Yanai what he made of his effort, and he said it was hard to say what it was all about. It wasn’t just about the methodology of digitally restoring the painting, though he had invested a great deal of time in that, and it wasn’t just about satisfying his curiosity about what such a restoration might look like, though that was also a part of the story. It also wasn’t about putting his own mark on a Leonardo, as Marcel Duchamp had done when he famously added a mustache to the Mona Lisa in a 1919 print. Whatever Yanai had done, its meaning was somewhere at the crossroads of these things, though it was also about the painting itself. The digital restoration, Yanai said, brings us closer to the original. In the middle of the process, as he became intimate with its every corner, its every color and texture, he couldn’t shake the feeling that the painting had also become his own. Now, at the end, he no longer saw himself in the process. When he looked at the painting, what he saw was a contemporary artwork—a representation of all humanity holding a fragile world in his hands. It’s a beautiful image, he said. People had been so busy talking about its authenticity that they had missed this essential aspect of the painting.

In the end, he said, had he known the road he’d need to take to arrive at this point, he wasn’t sure he would have started. He likened the whole process to standing at a chasm with only enough raw material to build a bridge halfway across. You start building and get to the middle, but then you have to take the bridge you’ve built, while suspended in midair, and use the same raw material to build the second half. Then, having reached the other side, you have to build the bridge again in the opposite direction to get as close as possible back to the original.

All other matters aside, I asked, had the experience given him any new insights about himself as an artist? He chuckled and said that it had actually reconnected him with his roots. He’d gone back to his old notebooks, to the drawings he’d done as a teenager when first starting to paint, and found copies he’d made of Leonardo’s drawings. He pulled a few of these out to show me, and I recognized one image at once—the head of an old man believed to be a self-portrait. It felt like a sign. I finally shared with him my own thoughts about Leonardo and the possibility that the Salvator Mundi was also a portrait of the artist.

I suggested we put his final image next to images that were believed to be portraits of Leonardo—including the drawing he had copied as a teenager. He opened some tabs up on his computer. It was hard not to be moved. The sharp nose. The penetrating eyes. The delicate eyebrows. The unique curve of the mouth. Even a split beard. It was uncanny. It was all there. It was, without a doubt, Leonardo.

I cannot overstate the power of the moment. The symbolism of the painting disappeared, and I saw before me a person all too aware of the fragility of the world in which he lived and from which, unlike the immortal figure in his painting, he would one day have to depart.

I looked over at Yanai, who had given years of his own life to resurrecting the dead, and had another thought. If Leonardo painting Jesus was really Leonardo painting himself, and Merleau-Ponty writing about Leonardo was in reality Merleau-Ponty writing about himself, was it possible that Yanai’s restoration of the Salvator Mundi was in reality Yanai’s restoration of himself? Perhaps. But Leonardo had also painted Jesus, and Merleau-Ponty had also written about Leonardo, and Yanai had, regardless of anything else, also restored the Salvator Mundi—endowing it once again with the most important element lost along the way, something that could never be reproduced by technical means alone. Emotion.

Learn more about Yanai Segal’s digital restoration project here.

The post The Whole World in His Hands appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Stanley Kunitz’s poem “The Portrait.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “The Portrait” by Stanley Kunitz appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Rabindranath Tagore’s poem “The Flower-School.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “The Flower-School” by Rabindranath Tagore appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Wallace Stevens’s poem “Sunday Morning.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Sunday Morning” by Wallace Stevens appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Grace Cavalieri’s poem “Three O’Clock 1942.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Three O’Clock 1942” by Grace Cavalieri appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Audre Lorde’s poem “Black Mother Woman.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Black Mother Woman” by Audre Lorde appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Hart Crane’s poem “My Grandmother’s Love Letters.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad

The post “My Grandmother’s Love Letters” by Hart Crane appeared first on The American Scholar.

In January 2020, in a remote, arid corner of southwestern Rajasthan, I was squeezed in the back seat of a Toyota SUV with my five-year-old son and Prachi and Prince Ranawat, a sister and brother, ages 23 and 18, from a dot of a town called Parsad. On a motorcycle, their father, Gajeraj Ranawat, followed. The driver propelled us along a parched roadway overgrown with candelabra cactus and bougainvillea, its pink and white flowers covered with dust. Sprays of yellow oleander spilled onto our path, and the screeches of langur monkeys echoed in the distance.

The family was leading me to a temple complex that once sheltered the so-called Tanesar sculptures, a set of 12 or more stone figures dating to the sixth century. Naturalistic, slender, luminously jadelike, and around two feet high, most of the sculptures depict mother goddesses (matrikas), with some holding a small child. Attendant male deities were also part of the set. According to art historians, the Tanesar figures were sculpted by an itinerant artisan guild as a form of patronage to local rulers. The sculptures were associated with fertility, but they were also linked with terrifying aspects of the all-encompassing mother goddess Devi in her manifestations as Kali and others—dangerous, destructive yoginis whose power eclipsed that of all the male Hindu gods combined. Over time, fearful villagers buried the sculptures in a field, hoping to contain their energy. But later, when the sculptures were feared no more, they were dug up and dragged to a small shrine to Shiva. There they were given pride of place in an enclosure to the side of the structure. At some point in their history, the figures became focal points for tantric prayer, with worshippers seeking a disintegration of the physical self to meld into universal consciousness.

For many years, the Tanesar sculptures remained an integral part of local religious life—unknown to anyone else. But around 1957, a prominent archaeologist in Rajasthan discovered the figures and then published an article about them in an Indian art history journal, making an inner circle of Indian and Western art historians aware of their existence. What followed was a story all too familiar in the world of art and antiquities: sometime around 1961, most of the Tanesar sculptures were stolen. From what I’ve been able to piece together, they were smuggled across the countryside, down to what was then Bombay, across the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic—to Liverpool and then New York. The American art dealer Doris Wiener, who ran a gallery on Madison Avenue, had a hand in the export of several of them. Another landed at the British Museum through a separate channel.

Very soon, the mid-century art world became enchanted with the sculptures. Art dealers, collectors, and museum directors eyed their potential worth. In 1967 and after, Wiener sold six or more sculptures from the set, for the equivalent of $80,000 each in today’s dollars, to curators and collectors who had more than an inkling of the dubious circumstances of the objects’ traffic. She sold one to Blanchette and John D. Rockefeller III and another to the Cleveland Museum of Art. The others passed from hand to hand before arriving at the world’s most revered collections of South Asian art, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

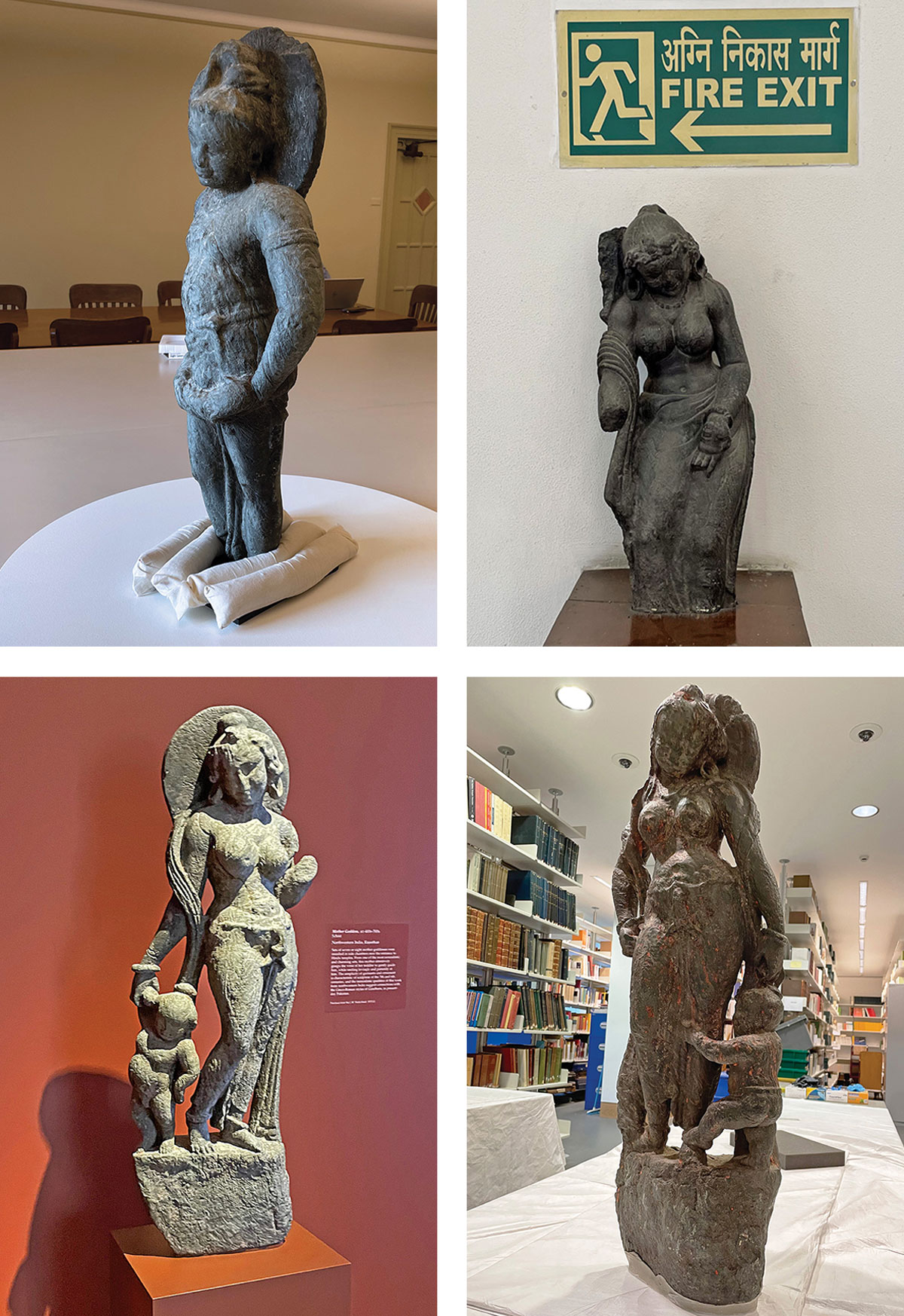

Mother Goddess (Matrika), previously on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was seized in August 2022 by the office of the Manhattan DA. (Courtesy of the author)

On August 30, 2022, the office of the Manhattan District Attorney, Alvin L. Bragg, issued a search warrant for one of the sculptures, called Mother Goddess (Matrika). At the time, it stood on a pedestal in the coolly lit gallery 236 of the Florence and Herbert Irving Asian Wing at the Met. The sculpture was seized, part of a sweeping sting targeting works acquired by Wiener as long as 60 years ago. Over the past decade, more than 4,500 allegedly trafficked antiquities have been confiscated by the office of the Manhattan DA. Instrumental in this work has been Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, a Marine colonel who led a government investigation into the looting of the Iraq Museum in 2003. Of those antiquities recovered by the Manhattan DA, nearly half have been returned to 24 countries of origin, with India receiving the largest share.

So many sculptures seized and sent home, each with its own story. It can be hard to see why any one of those stories matters in the particular. The repatriated artifacts are not as well known as the Benin Bronzes, for example, plundered from West Africa by British colonists, or the Parthenon marbles, removed by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s and now on display at the British Museum. They are not symbols of empire, nor are they the spoils of war. Rather, they are emblems of something more banal and arguably more pernicious—the practice of mid-century antiquities looting that took place on such a scale that it infected nearly every gallery of Asian art in the West.

The way forward is neither clear nor simple. In the fall of 2022, Mother Goddess (Matrika) lay in a crate in the Manhattan DA’s overstuffed storage facility while the search continued for each of the Tanesar sculptures sold through Wiener’s gallery in the late 1960s. Mother Goddess (Matrika) and at least four more deities from the set remain in legal limbo as lawyers for the Met and other American museums raise questions about who owned the sculptures at the time they were acquired by Wiener, and whether they really did belong to the temple at the time of their theft.

One of the Tanesar figures, the sculpture purchased by the Cleveland Museum of Art, is still on display there. Others remain, for the moment, in the custody of LACMA and the Allen Museum at Oberlin College. Beyond the purview of the U.S. legal apparatus, the Tanesar goddess at the British Museum currently resides among the dutifully cataloged collection of nearly eight million objects not on view because of space limitations.

The sculptures may languish in this liminal state—crated, underground, or imprisoned in storage—but then, the liminal is where the Tanesar goddesses have existed for many years.

In 2020, I was a Fulbright scholar living in the city of Ahmedabad. I’d been researching the story of the Tanesar sculptures, having chosen the case because it involved one of the few thefts where published photographs linked looted artifacts housed in Western museums to a specific origin site. I was drawn to the beatific, yet unfussy artworks—though it was only later, as I traveled across three continents to see seven of the sculptures in person, that I fell in love with them.

In art history texts, the village of Tanesar was said to lie in the steep hillsides between the cities of Dungarpur and Udaipur, along the border of southern Rajasthan and Gujarat state. No map showed a place called Tanesar or, as it sometimes appeared in museum catalogs, Tanesara Mahadeva. News articles were of little help. A few articles in the Indian press and a 2007 piece in The New Yorker mentioned Tanesar, but only as a footnote in a seemingly unrelated story—that of the smuggler Vaman Ghiya and his arrest. As far as I could tell, no journalist or academic researcher had visited the site since the middle of the last century.

The place to start was Dungarpur. On the taxi ride from Ahmedabad, my son and I encountered a landscape where algae-rich stripes of sedimentary stone—black, charcoal, green, and blue—shone in the roadcuts. The stone industry continues to thrive in this part of northwestern India, the source of building materials, sculptures, and architectural decorations. Quarry shops sold the blue-green schist known locally as pareva, and trucks rumbled by, carrying cubes of marblelike stone.

The next morning, at a hotel in Dungarpur, the concierge told me that his in-laws happened to worship at the temple I was looking for. He put me in touch with his brother-in-law Gajeraj Ranawat. Serendipitously, I received a text that same morning from my friend Abhi Sangani, an art historian in Ahmedabad, who’d gotten a tip from his cigarette vendor with the approximate location of the temple.

This is how we ended up in the back seat of that Toyota SUV. And it was during that journey with the Ranawat family that I finally understood why finding the temple site had been so difficult. As I traced the turns of the road on my phone’s maps app, the coordinates for a temple came into view. I zoomed in. Taneeshwar Madahav Tample, the map read in English, a clumsy transliteration of the Hindi phrase beneath it: Taneshwar Mahadev Mandir. The photograph linked to the map showed the temple entryway, with its name in Devanagari script visible in blue lettering—Taneshwar Mahadev. Having studied Sanskrit and yoga philosophy, I knew that Taneshwar (or, given the conventions of Hindi and Sanskrit, Tanesvar, Tanesvara, or Taneshwara) means “Shiva” and that the phrase Taneshwar Mahadev translates to “the lord Shiva, Shiva who is the greatest god.”

Therein lay the answer to the first mystery of this tale: Tanesar was a temple, not a village. Imagine if someone had named New York City “Beth El” because of the synagogue on East 86th Street. No wonder journalists never reported firsthand from the Taneshwar Mahadev temple. If they’d been looking, they would have been searching for a village that did not exist. It’s quite possible, of course, that no other outsider had ever tried to find “Tanesar” village. After all, asking exactly how a smuggled object reached an esteemed gallery in a Western museum was not common practice until recently.

Now, after parking off the jagged road, we passed a row of stalls selling items for worship—coconuts, incense, matches, squares of metal foil, rectangles of red nylon mesh trimmed with gold thread—and followed a grand stairway up to a temple plaza. Revelers in brightly colored saris danced in a circle while men played drums and long-necked, stringed gourds. Incense and oils released a sticky, noisome odor. Smoke filled the air, and langur monkeys leapt between temple structures, with the Shisha mountain rising behind them. A priest in a white tunic and flowing dhoti pants chanted in Sanskrit and led the worshippers in a fire ceremony meant to bring auspicious energies from the planets.

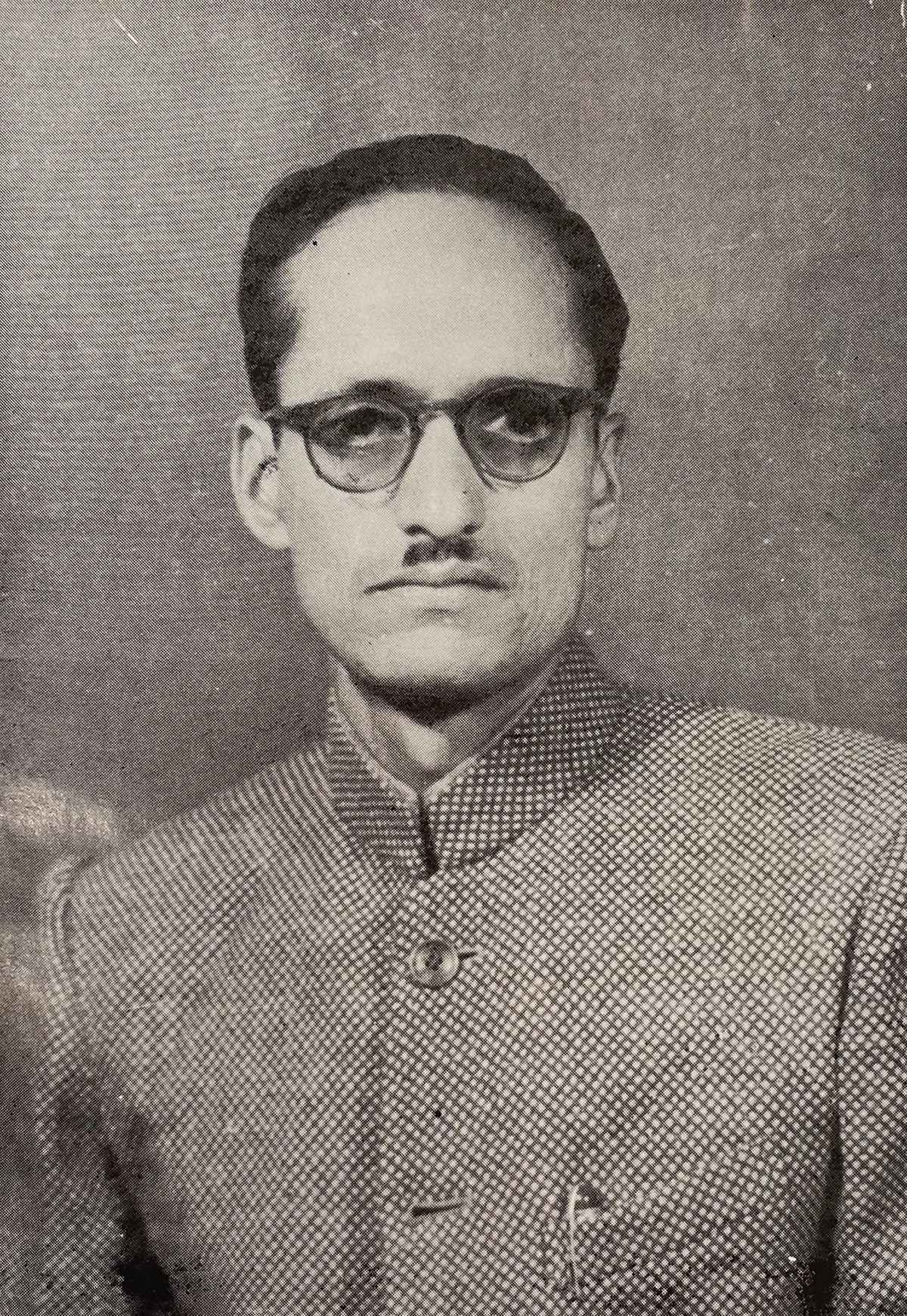

Ratna Chandra Agrawala devoted his life to the study of Indian art and artifacts. In the 1950s, he came across the Tanesar matrikas during an exploration of southwestern Rajasthan. (From Ratna-Chandrika: Panorama of Oriental Studies)

As several villagers gathered around us, my son went off to play, jumping from the retaining walls separating the plaza and the stalls and poking a stick into a warm spring that trickled down from the mountainside to the plaza. Then, with Prachi Ranawat translating, the villagers began telling me about the statues’ theft. Everyone, it seemed, knew a version of the story, which had been passed down from parents and grandparents. According to one account, a temple guard awoke one morning to discover that most of the sculptures had been spirited away in the deep of night. Alternatively, a white car arrived in the dark and took the sculptures away. Or a madman came and stole the sculptures. Or a man known to villagers by the nickname Kadva Baba came and spoke to the priest in private; money was exchanged, and shortly afterward, the sculptures were taken away. The oral history of the temple may have recorded many possible scenarios, but certain facts remained constant. Temple lootings were common in the area at the time. And although villagers often reported the thefts, police rarely recovered the loot.

I heard a great deal that day about how important the sculptures were to local life. “If someone didn’t have a child,” one person said, “they worshipped the goddesses so they could have one. If someone was suffering from a disease, they also worshipped the goddesses.” Another offered that worshipping the goddesses could bring a male child. The temple itself had been the site of a famous miracle, others said, a legend I heard about in greater detail on one of my later visits. A priest would tell me a version of the famous story of Surabhi, a cow that would wander off from its home every day and come home dry. Surabhi’s owner, angry that someone was apparently stealing his milk, secretly followed the cow to the temple, where he watched as its teats released a flood of milk onto the ground. This it had been doing every day, he learned. Later, a statue materialized on that very spot, an emanation of Lord Shiva. “That was how everyone knew that the temple was magical,” the priest explained. And in the same storytelling voice, he said, “Thirty-five years ago, a goddess statue was stolen from here. Now, the government is going to send her back.”

One thing was certain: the temple community would settle for no compensation, monetary or otherwise, in lieu of the sculptures’ return.

In the middle of the 20th century, Ratna Chandra Agrawala was the foremost archaeologist in the state of Rajasthan. He was the author of more than 400 essays and articles, many punctilious in their detail. His life’s work as a scholar and as director of museums and archaeology for the state led him to register art objects, preserve many of them in two regional government museums that he founded and managed, and argue for their importance in Indian and international arts journals. There was nothing shoddy about his work.

Born in 1926, Agrawala trained as an archaeologist in pre-independence India. In 1946, he worked on the dig that uncovered parts of the Indus Valley site of Harappa, in what is now Pakistan. Art historians who knew Agrawala during the following decades remember his utter devotion to Indian art history and his palpable joy when asked to discuss this subject, still underappreciated in the 1960s and ’70s. In one photograph, Agrawala appears in the garb of India’s educated elite of the era, wearing a Nehru jacket and thick-framed glasses and sporting a trim, narrow mustache. His thinness accentuates an intent expression in his eyes, in which I imagine—perhaps because I’ve researched his background—a hint of both pain and triumph.

Around 1957, during what Agrawala described as “exploratory tours in the regions of Udaipur and Dungarpur,” he encountered the Tanesar sculptures. For Agrawala, the artworks possessed a pleasing dissonance, with their classical proportions, indigenous features, and the sparest of religious accoutrements. They immediately won his adoration. In 1959, he described what he had found in the Indian journal Lalit Kala. In 1961, Agrawala published a second article in Lalit Kala discussing the sculptures’ art historical importance. Included were photographs of 10 of the sculptures snapped outdoors near the temple. Leaning on rocks, the gods and goddesses resemble crime victims. They are encrusted with dirt and an unguent mix of substances related to worship, which likely included milk, ghee, vermilion, and ash. Agrawala stated that the sculptures were currently being used for worship (“under worship” was the phrase he used). He went on to lament that the sculptures “remain completely besmeared with red lead and oil. It is therefore not possible to clean them for study.”

A third article appeared in the French journal Arts Asiatiques in 1965. Here, Agrawala published photos of an additional sculpture and more fully described the artworks and their material, the luminous blue-green schist. One of the pieces, he wrote, “presents a lady with her head bent in a graceful pose. This is unique in Indian Art. She puts on the typical sārī and the scarf is appearing on her right arm. The facial expression here is extremely elegant and so also is the case with round ear-lobes, single beaded necklace, broad face, robust breasts, etc.” He declared the sculpture to be “a piece of superb workmanship,” adding, as an aside, “the hair decoration is equally charming therein.”

The 1959 article identified the temple as Tanesara-Mahādeva and its location as being near the village of “Parsada,” a Sanskritized version of Parsad. Agrawala didn’t mention Parsada in his 1961 article, though he did cite his first article in the footnotes. But by the time the sculptures had arrived in the West, it was the 1961 article, not the original publication, that was the standard source on the subject, the primary bibliographic reference for authors of museum catalogs. This is how Parsada got dropped from the record, replaced by the fictional Tanesar.

But why didn’t Western museums track down Agrawala’s primary source material? One day, I arrayed before myself, in chronological order, each bibliographic reference to the Tanesar artworks from 1959 through the 1980s, hoping to understand how this scholarly laziness had occurred. The first mention of the sculptures in an American publication appeared in a 1971 issue of the Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin of Oberlin College. That issue was devoted to an exhibition of works belonging to a prominent collector and Oberlin alum, Paul F. Walter. Among the artworks that Walter had recently donated to the Allen Museum was Deva, a Tanesar sculpture featuring a lithe young man with a serene, transported expression, carved from the blue schist.

One of the essays in the Bulletin, written by the art historian Pratapaditya Pal, curator of Indian art at LACMA, described five sculptures from the Tanesar set that Wiener had acquired and then sold to prominent American curators and collectors. This included images of an additional sculpture, bringing the total number documented in photographs to 12. The essay, a tour de force in interpretive writing, marked the sculptures’ entrée, like debutantes, into a larger art historical conversation beyond the limited audience of India’s rarefied Lalit Kala.

Pal’s elegiac descriptions explored theories regarding the identities of the gods and goddesses, their art historical connection to other artworks from nearby sites and distant centers of artmaking during the fourth- to-sixth-century Gupta Empire, and the trope of the mother in South Asian art. “Each of the pieces magically seems to have captured, as in a candid snapshot, a fleeting moment of joy and playfulness,” he wrote. The matrika in the Cleveland Museum of Art “appears to be smiling as she tries to restrain her child. This sense of radiant motherhood is more explicitly expressed in these matrikas from Tanesara than in any other Indian sculptures.” Deva had “the physical properties of a human being,” and its face evoked “supra-human serenity and compassion.”

The Taneshwar Mahadev temple complex, where the sculptures had been housed. Local residents tell several versions of the story of how the figures were stolen. (Courtesy of the author)

The problem was, for all the flourishes of Pal’s lushly detailed and celebratory narrative style, the essay was also riddled with mistakes. It incorrectly identified the “Tanesara-Mahadeva” temple as a village (with a footnote erroneously ascribing that detail to Agrawala’s 1961 article). The name of the famous regional rock was changed from pareva to pavena. And the name of a sister site that Agrawala had also explored morphed within the article from Kalyanpura to Kotyarka. These mistakes and others subsequently appeared in later works of scholarship.

It seemed odd that the editors didn’t catch these lapses. But when I read the introduction to that issue of the Bulletin, I realized that a general romantic sensibility had prevailed over the mundane requirements of scholarly fidelity. “To Western ears,” wrote Richard Spear, the Allen Museum director, “Bhagavata Purana, Ramayana and Ragamala are strange sounds, as remote as Malwa, Hyderabad and Jaipur.” “Tanesar” was not a place where people lived and worshipped but a fanciful, fairy-tale locale. Further embroidering this theme of exotic-domestic interplay, Spear described Walter, the collector and donor, as someone who was “as likely to be met in the studio of a young artist in lower Manhattan or a London auction of Whistler etchings as in the Doris Wiener Gallery of Indian Art.” The relationships between dealer, collector, and museum curator were cozy enough to completely subsume any question of how the artworks were attained.

The fairy-tale atmosphere also created an illusion of buyer innocence. It was all too common in mid-century America to deflect blame from those who acquired artworks that had been purloined by shady dealers. A charade of not knowing the specifics of any origin site insulated those at the top of the antiquities trafficking chain—the Rockefellers, respected collectors, and museum curators who had purchased or accepted the sculptures as donations. Even today, this false ignorance prevails, in spite of its illogic. “If you didn’t legitimately acquire the property in the first place, you can’t pass on title,” Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Bogdanos told me. “A stolen object never reacquires goodness. Once stolen, always stolen.”

Clockwise from top left: Tanesar matrikas in the collections of Oberlin College,the National Museum in New Delhi, the British Museum, and the Cleveland Museum of Art (Courtesy of the author)

By drawing attention to the Tanesar artworks, Ratna Chandra Agrawala—no matter how noble his motives—ended up contributing to their theft. He was part of a nationalistic movement, just a decade after Indian independence, to increase global recognition for indigenous statuary. This mission was shared by the editors of the Bombay-based journal Marg, which in 1959 cited Agrawala among the Western and Indian art historians and archaeologists who inspired the “intelligentsia” and “men and women of culture” to appreciate “the remarkable tradition of carving which has miraculously survived in Rajasthan.” The editors also “earnestly appeal[ed] to the archaeologists” to “accord proper display” and facilitate “direct contact with the unknown masterpieces.” Agrawala did this, in part, by relocating two of the Tanesar sculptures to his government museum in Udaipur.

Today, these remain in the Indian government’s custody, displayed in underwhelming circumstances that would surely rankle Agrawala’s ghost. One is easy to miss, in a busy section of hallway at the National Museum in New Delhi, crowded between a potted plant and an exit sign. The day I visited, crowds of chattering secondary students in government school uniforms raced past, oblivious of the goddess. The other matrika, more dispiritingly, resides at an Udaipur government gallery, in a desolate room that is often closed to the public. When I finally managed to get in, the lights didn’t work, and chipmunks were scampering along the rafters. The matrika stood behind a case so rarely dusted that I could barely read the identifying label through the glass. But when I was able to make it out, I saw that the label had been swapped with that of a nearby sculpture from a different site. If Agrawala might have frowned at this sad scene, he also may have worn a small smile, knowing that the sculptures had been kept safe from looters all these years. Here the matrikas rested, ready for future generations—perhaps even those scores of secondary students in New Delhi—to embrace the appreciation of Indian art that he and his cohort had worked so hard to instill during the 1950s and ’60s.