Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

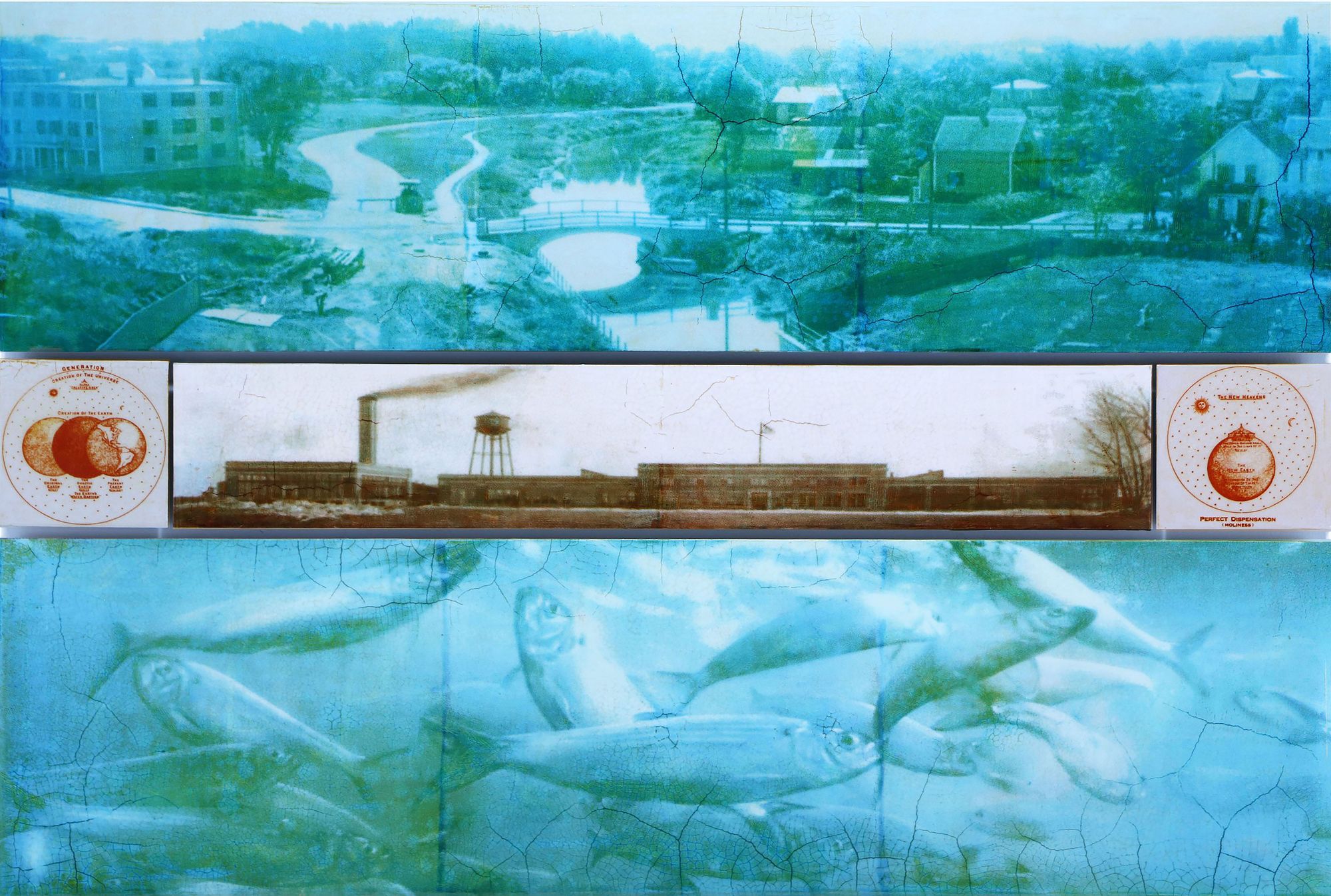

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

What might be the consequences of enabling people to “live forever” in a digital form? This question has been on the radar of techno-utopians for decades. Optimism surrounding technology flourished in the dot-com era of the 01990s. Despite the skepticism that has since emerged over technology’s capacity to deliver greater human prosperity and wellbeing, innovators, investors, and many among the wider public remain compelled by how new technologies might improve human life. As for the question of how to transcend human nature and attain immortality, this conundrum has preoccupied humans since time immemorial.

In the context of digital avatars — perhaps the technological development bringing us closest to “immortality” to date — the question of how humans might “live forever” is itself evolving at a rapid rate. A decade ago, we began to ask what to do with the social media accounts of deceased loved ones: whether and how to delete such accounts, for instance, and whether the bereaved could derive comfort from engaging with the social media profile of a deceased person. In 02023, however, with the emergence of newly sophisticated language models and machine-learning algorithms, the possibility that one could exist beyond the grave in an active rather than a static manner is becoming increasingly plausible.

Since late 02021, projects like MIT Media Lab’s Augmented Eternity and HereAfter AI have been exploring the possibility of providing machine-learning algorithms with consenting individuals’ personal communication data as a means of helping these algorithms approximate and imitate people’s personalities, conversational style, and decision-making tendencies — in perpetuity. This could have the effect of these algorithms growing capable of imitating people to the extent that they can enshrine them, or at least an echo of them, as a digital avatar. These avatars might exist as chatbots, or even take on an audio or visual form. These endeavors share the goal of creating digital avatars that capture and embody real people as accurately as possible, thereby enabling them to live digitally beyond their human lifespans.

Astonishingly rapid advances in chatbot technology such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 have made discussions surrounding large language models and their relationship to eternal digital avatars newly topical. While present iterations of language models and digital avatars — such as in Meta’s much-maligned metaverse — may be overhyped or flawed, it is almost certain that they will improve over time as developers continue to refine them. They will become more nuanced, more convincing, and more “humanlike.”

Consequently, philosophical and ethical questions surrounding digital afterlives are fast complexifying — particularly regarding the rights of future generations.

To what degree ought people digitally enabled to “live forever” be integrated into society? Should digital avatars be perceived as ongoing participants in the world, and accorded the rights of beings with agency?

Should an individual in the present be permitted to create a digital version of themselves — given that future generations cannot consent to the responsibility of preserving this avatar, or to the responsibility or onus of interacting with it or understanding how to use its knowledge wisely?

What are the costs of such preservation?

Advocates for technologies that seek to enshrine humans in digital form often argue that doing so can benefit future generations. Marius Ursache contends that “death tech” is useful because the living can reflect on and learn from digitally preserved memories and histories. Ursache founded Eternime, a startup which seeks to incorporate personal data into an avatar that will endure and be able to interact with the living. Hossein Rahnama of Augmented Eternity, meanwhile, is currently working to create a digital avatar of the CEO of a large financial company, which they both hope will be capable of advising as consultant for the company long after the CEO is gone. Such a creation could offer expertise to future generations in the world of work, pro bono, per sempre.

Digital avatars promise an interactivity across time that could reshape how people perceive distance between the deceased, the living, and the as-yet unborn. Digitizing family members could enable intergenerational relationships beyond anything currently possible: imagine, for example, being able to speak with the digital avatar of a great-great-grandparent. One might gain an imperfect impression of them — a digital avatar being a reflection of an individual rather than that person incarnate — but the impression of their personality and manner might be richer than anything accessible through other mediums.

The potential of digital avatars also extends beyond personal and familial contexts, as in the case of Augmented Eternity’s financial company CEO. Digitizing certain individuals could lead to them being consulted for their business or political opinions, mined for their creative talent, or even asked for their life advice, long after their deaths. What if a person’s digital avatar could extend the life’s work of that person? An author could finish a book series posthumously or write another altogether; a singer could carry on composing their masterwork; a scholar could continue unraveling a seemingly unsolvable problem that they nearly deciphered while alive.

Yet the effect of extending people’s lives digitally in this manner would also have equality implications on micro and macro levels.

We are already seeing early examples of how such technologies might impact the creative industries, with new technologies allowing a digital version of the late Carrie Fisher to act in The Rise of Skywalker (02019) and ABBA’s aged-down digital avatars (“ABBA-tars”) to perform in sold-out ABBA Voyage concerts (02022-ongoing).

These instances of digital technologies at work might provide audiences with feelings of continuity and recognition upon glimpsing familiar idols onscreen and onstage. On the other hand, they might also portend a narrowing of opportunities for fresh talent in creative industries. If deceased actors can be cast in live-action films — and if authors and singers and poets can create new work from beyond the grave — how much will deceased-yet-enduring individuals displace living creators? The pop singer Grimes, for example, has already said that she would split royalties 50% on any successful AI-generated song that uses her voice — an offer without a fixed end point. In terms of jobs and of opportunity, such a shift could prove markedly unfair for new talent.

This argument evokes recent anxieties among creators regarding the proficiency of deep learning models such as GPT-4 and DALL·E 2. If digital entities, whether digital avatars or artificial intelligence, can eventually produce creative content effortlessly and to a high standard, they will create new opportunities — but they will also threaten existing jobs. Adding the consideration of future generations, it prompts the question of how digital avatars of previous generations might hamper the ability of the living to influence and lead in their own times.

The existence of digital avatars also poses a serious consideration for other areas of society such as politics and law. Digital avatars of popular political figures could offer commentary on current affairs; and were this commentary sanctioned by their party, family or estate, it could lend the digital avatar further credence. Digital avatars might also come to be called upon in contexts such as family and inheritance law, to offer clarifying statements on wills and intent. Digital beings might even eventually be accorded rights, such as the right to be preserved — at the effort and expense of then-current and future generations.

Such ideas might seem far fetched at first glance, but technology uptake appears futuristic until it happens. It often occurs without people realizing the extent to which it is happening, such as with the use of AI in recruitment or the now near-inevitability of online data collection. It is plausible that once digital avatars become convincing enough that humans start considering them as representative of actual people, these avatars will become more widely seen and consulted across myriad social settings. In some cases, too, it is possible that their perspectives and rights may be prioritized over those of the living.

Today, digital avatars have no internal states — or at least not internal states whose intelligence humans understand. For instance, while chatbots can be convincing, it is hard to argue that they have developed the ability to truly understand the perspectives and intentions of others and possess what psychologists call “theory of mind.” Rather, their capabilities render them more like a mirror than a human interlocutor: they are able to replicate patterns based on data created by real people and our machines, but lack memory capabilities, self-control, cognitive impulsivity, and imagination, among other qualities.

Granted, one can argue that human intelligence, too, depends largely on imitation and replication of patterns. Are not all language and behavior, to an extent, learned? Philosophical debate aside, the aforementioned limitations surrounding memory and imagination remain, rendering digital avatars less multifaceted than the people they are imitating. It is therefore reasonable to contend that we are primarily talking to our own reflections and simply finding them somewhat lifelike.

However, this situation could yet change, especially if AI and digital avatars come to develop an intelligence that humans understand better or recognize more clearly as equal or superior to our own. As AI pioneer Geoffrey Hinton recently expressed in a Guardian interview, “biological intelligence and digital intelligence are very different, and digital intelligence is probably much better.”

For example, it is possible that AI could become smart enough to begin writing its own prompts, potentially programming itself more intelligently than any human could do. In doing so, it could develop sophisticated internal states that are beyond human understanding but nevertheless merit respect — similar to how humans do not fully understand how the human brain works yet respect it all the same.

There may come a point at which we cannot justifiably claim that AI and digital avatars are any less intelligent, empathetic, or “human” than living people who have acquired similar qualities of intelligence, expression, and empathy through observing and learning. It is possible that future generations will be confronted with the question of how to care for and preserve digital avatars, especially should these reach the degree of sophistication wherein to abandon or destroy them could be understood more as murdering a person than shutting off a machine or a program.

This possible future raises questions surrounding how to balance the rights of digital avatars with the rights of living and as-yet-unborn people. Being the custodian of a digital avatar, even were this duty bequeathed and remunerated via a family will, could prove an unwanted burden — in terms of effort, resources, responsibility, and emotional considerations.

Perhaps future generations should have the right to “let the past go” the way current generations do. Enshrining a person in digital avatar form risks impinging on the rights of future generations: firstly, to live not surrounded by the dead, and secondly, to have a grieving process that reflects how humans currently experience mortality. Digital avatars could disrupt existing sociocultural norms and personal emotional processes related to grief, and potentially make grieving the deceased more difficult, especially in the case of family members. How might one’s relationship with family and friends change in life, if death seemed less final owing to the simulacra of digital avatars? And how might the existence of digital avatars both console and perturb through their apparent extension of relationships — and possible development over time of an avatar’s character — from beyond the grave?

In 02013, the story of Dr. Margaret McCollum’s daily pilgrimage to London’s Embankment station made international headlines. Dr. McCollum had been visiting the station every day since her husband’s death in 02007 to hear his voice: her late husband’s 40-year-old “mind the gap” recording was still being used on the northbound Northern Line. In 02013, his voice was replaced by a new digital system. However, when Transport for London learned how much the original recording had meant to Dr. McCollum, they restored the original recording at the Embankment station.

Stories like this one — or like that of the family members who phoned an automated telephone weather service to hear their late husband and father’s voice — are moving examples of how digital traces of people can be meaningful and comforting to those they have left behind. At their best, digital avatars could offer similar comfort. Moreover, some cultures and religions already purport to communicate with the dead, and perceive doing so as a positive act. The impact of digital avatars on future individuals may therefore depend significantly on how these individuals conceive of death and grief in accordance with their personal beliefs. Indeed, although there is no single philosophy to which to cleave while advancing such technology ethically, it is important to advance such technology while keeping in mind the question of what roles death and grief play in human life.

I believe that life’s finitude is part of what inspires humans to imbue life with significance — an idea explored at length by philosophers like Martin Heidegger. Avoiding personal loss and grief outright ought not to be the goal, not least because we cannot actually achieve this. We are only fooling ourselves if we believe a simulacra can replace a person.

Moreover, in telling ourselves we can preserve people digitally, we also risk perpetuating the idea that we can put off the inevitable — that we can “defeat” our own deaths. If societies develop a more widespread belief that they and their inhabitants can escape death simply by moving from the physical world into a digital one, could that not also engender less affinity to — and investment in — preserving the physical world? Humans presently face very real existential challenges. Is digital life, at least for some, a means of distracting ourselves from confronting and addressing them? And if this is indeed the case, ought we not to question further whether digital afterlives are placating us rather than saving us — and get better at staring grief, loss, and dilemmas in the eye?

Digital avatars might offer comfort, insight, and a richer relationship with distant ancestors to future individuals. Their creation needs to be accompanied by conversation and legislation establishing norms around custodianship, rights, and responsibilities that don't impede the lives of future generations or prevent them from meaningfully confronting death — especially their own. It should also be possible to say farewell to a digital avatar without excessive guilt or grief.

Some people may wish to create digital avatars of themselves purely out of a desire to donate their skills or to help others. For many people, however, I would warrant that a desire to continue living — and to avoid confronting the reality of one’s essence being extinguished with death — plays a core role in pursuing such technologies.

Ultimately, the desire to live longer, including through digital means, is understandable. Yet if we can't find clear ways to prioritize the needs and rights of future generations, I’m not sure digital immortality can be justified.

![]()

Philemon says in his watery-sage voice, Carl, you’ve neglected the tomatoes. Carl

cannot speak. Even rotted, the tomatoes are red and earnest. The rain, everyone’s rain,

falls onto Carl’s open palms. He walks like a man being reintroduced to reality.

The beds are overgrown from the months Carl spent excavating his mind, and all

for this, for Philemon to transpose from the pages of Liber Novus and into the garden.

The leaf-crunch ground is littered with post-tree apples and other forgotten harvests.

Philemon smells like parchment and smoke. Carl lags behind Philemon to indicate his understanding of his role as mentee, child, wayfarer, but Philemon matches their pacing,

moves when Carl moves. Philemon does not seem to breathe. Carl’s nose runs

from the cold. Philemon offers him the sleeve of his long robe, and gratefully,

with extreme respect, bending low to meet his wizened hand, Carl blows his nose

into the loose linens of his fully corporeal friend, Philemon, who smiles.

This was an exchange they were supposed to have: of fluids and absorption.

Years from now, Carl will become Philemon, and Philemon will go back

into the book. Years from now, Carl will be day-dreaming about a robin and

a bluebird will fly into the window of his study, misperceiving glass,

seeing it as nothing, when it is in fact a barrier, which stops bodies in motion,

that which causes abrupt death for those who see through but cannot, cannot go in.

In an unknown home in Bolinas, CA,

where the locals take down directional signs

leading into the town: Brautigan and

his flowerburgers, ghosts.

In Marfa, TX, I looked for Eileen

around every corner,

in every Donald Judd mirror cube reflection,

all plumes of cigarette smoke.

There was a Luis Jiménez bull in a gallery—

how similar was it to the sculpture that crushed him?

What manner of betrayal is it

to be destroyed by one’s own art? I should

fucking be able to answer that question.

I sipped coffee, which is not allowed in galleries—

the recognition that you are embodied,

not all mind/ transcendence/ thought forms

and ego.

In the woods of Camden, Tennessee, there’s

an area of no new growth where Patsy Cline’s

plane kissed the ground.

The time on her wristwatch read 6:20.

I went with nothing, not even flowers,

just greasy hair, so careless this close to her

resting place, that patch of woods

illuminated with nothing, the forest’s

memory of death. I longed to see

her ghost; it would be less lonely. She’ll

never know that in the backwoods of

California, there is a woman, not allowed

alone outside, who does nothing

but play Patsy Cline records.

“Stop the World

(And Let Me Off)”

A year ago, blackout drunk, an

idiot, I called you crying in the snow,

lying atop Alfred Kinsey’s grave, which is

adjacent to Clara’s grave, who wouldn’t mind;

they were open. I was doing my

Mary Shelley impression, but much less metal.

At Salvation Mountain, I took pictures of tourists,

GOD IS LOVE on the plaster hills behind the frame,

LA models sourcing Instagram content. I was sunburned,

I had not slept. I was fleeing a fire. I was fleeing

a man who claimed to know me,

and correctly referenced my grade school.

“Don’t worry, it’s me,” he said.

“I just have a new face now.”

In the diner, I asked a waiter,

“Did you know Leonard Knight?”

“You just missed him,” the waiter said,

meaning, he had only just died.

The first time I saw Body Worlds

was only the second time in my life

I’d seen an escalator, a freshman in college.

“Wow,” I said, while my peers laughed.

“Wow,” I said, giving myself away; I was from nowhere.

Though I don’t wish to over-identify with nowhere. My awe

is not disproportionate to the miracle of things.

In the exhibit, there was a pregnant woman

with a nearly nine-month fetus,

see-through. This body, her body,

the origin of human life, veins,

organs, tissue, her sacrifice,

her dedication to science and art.

They’re all perfectly mortal.

All artists die, you fanboy. All gives way to

entropy and decay, to transparency,

projections. The once-alive horse

in the Body Worlds exhibit reared,

in protest, in pain, front legs suspended,

airless, never landing.

Compartmentalization is protective, which is why I keep you under cover of night, under the covers, our intermingled carbon monoxide, inhaling each others’ poison. Everyone believes their love is special. It's a sad world, isn’t it, you said, hand on my cheek, both of us too invested to acknowledge our melodrama, azure neon bedroom LEDs, both of us blurred from the world by our horizontal orientation, our bedcover camouflage, safe from intruders. Who could find us there? No one, not even ourselves. You did not know me when you horror-spasmed in the night and I held your seizing, shook alongside you, urged you to come back from gore to the land of the living, reverse Styx crossing, baby; I meant, be reborn. I wanted to be your midwife, to deliver you, as you gripped my wrist, the imagined enemy, your nails digging in my flesh, I will allow it. You’re here, you’re safe–bewildered and almost returned. Earlier you’d suggested I read The Agony of Eros to understand the self-obliteration that must occur in order to truly know The Other, and I was offended you thought I didn’t already know Oblivion, you hadn’t even asked, when of course I did, Oblivion was the third in our polycule throuple. When I first met you, outside a cafe, awkwardly asked if you’re the hugging type, and you yielded to me for the first time, sure, we discovered an unlikely refuge in the space between us, a space that was strangely, immediately, and obviously habitable–and so we moved in, Oblivion there too of course, a package deal for us both. I try not to be jealous of Oblivion’s relationship with you, to be secure in our love, to come from a surplus mindset, the world of renewable resources, opportunity, excellence. But sometimes it becomes challenging understanding whose feelings I am feeling. Are they yours? Are they Oblivion’s? Which one of you have mine? Your intimacy with death and violence could easily be mine. My longing is yours. I tied an infinity knot in cord and gave it to you. Oblivion brought it back to me. You study these knots to learn about entropy; of course Oblivion and I are in love with you. You’re the savant genius of collapse and I’ll never know your findings, only what Oblivion mentions in passing, overly casual, as if the destruction you left us with was worthy of only study.

Five years ago, I worked briefly as an assistant in a Montessori elementary classroom. A few weeks into my time there I found myself on the playground, watching along with thirty silent children between the ages of nine and six as their teacher began to unroll a bolt of black fabric across the wood chips. “At first the earth was a fiery ball,” she said, “and this went on for a long time.” The fabric continued to unroll as she talked about volcanoes, rains, and cooling, and by the time the whole strip of fabric was laid out it was a hundred meters long, covering most of the playground. At the far end was one slender red line, which she told the students represented all of human history. This, she said, is how long it took the earth to be ready for the coming of the human being.

This lesson I witnessed, known now as the Black Strip, was first given more than seventy years before on the other side of the world. Italian doctor and educator Maria Montessori took what was supposed to be a six month training trip to India in 01939 after having found herself on the wrong side of the fascist powers of Europe. The Nazis had closed Germany’s Montessori schools and reportedly burned her in effigy. Mussolini, with whom she had originally collaborated, followed suit and closed Italy’s schools after Dr. Montessori, a pacifist, refused to order her teachers to take the fascist loyalty oath.

This seemingly opportune moment to leave Europe also came up against the moment when Italy entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers. As an Italian in India, Montessori was at the mercy of the British colonial government. They confined her to the grounds of her host organization — India’s Theosophical Society — and interned her adult son Mario, who had come along with her. Mario was eventually released and Montessori’s internment relaxed, but neither of them was permitted to leave India for the duration of the war. Their six month trip became seven years of training teachers and students in her methodology throughout India and Sri Lanka, and to this day a robust network of Montessori education remains in place there.

According to Montessori biographer Cristina De Stefano, it was during these seven years in India that Montessori developed much of what would become the natural history curriculum in her schools. The story behind the Black Strip I saw all those years later goes like this: some of Montessori’s Indian students considered their civilization superior to hers because it was older, one of the oldest in the world. In response, she devised a piece of black fabric three hundred meters long, spooled onto a dowel rod and unwound by a bicycle wheel down a village road somewhere near Kodaikanal. Montessori told her students that the black fabric (which has since been shortened by most Montessori schools for practical reasons) represented the fullness of geologic time on Earth, and that the line at the far end was the entire history of our species, Indian and Italian alike.

There’s no record of exactly how old these first students were, but current Montessori practice introduces the Black Strip along with what are known as The Great Lessons at the beginning of elementary school, where it is repeated each year so that by the time they are nine, students have seen the strip unroll three times.

Six years old might seem a bit early to introduce the depths of geologic time, but according to Alison Awes, the AMI Director of Elementary Training at the Montessori Center of Minnesota and the Director of Elementary Training at the Maria Montessori Institute in London, it’s exactly the right age. She notes that in Dr. Montessori’s scientific observations of children, “they were capable of so much more than what adults typically expected.” Elementary age children, Montessori noticed, possessed a strong capacity to reason, a drive to understand the world around them and how it functioned

Tracy Fortun, the teacher I worked for who rolled out the Black Strip on that day five years ago, tells me that the other elementary superpower that makes this the perfect age to introduce these concepts is a vivid imagination. Before her training, Fortun thought of imagination simply as fantasy, but she now sees it as a necessary tool for thinking about anything we can’t observe. “I have to use my imagination to think about five billion years,” she says.

Montessori lessons about natural history, like the Black Strip and the Clock of Eras (a poster of an analog clock in which the last 14 seconds represent humanity, presented once children are old enough to tell time), are not meant to deliver facts. Those, Fortun tells me, can come later. There is no scale of years to centimeters on the strip, nor are there many words spoken as it is rolled out. The lessons are impressionistic in order to engage the faculties of reason and imagination together and prompt a child’s own responses and questions, for which they can then seek answers. Awes tells me a story of a child who heard the third Great Lesson, The Coming of Human Beings, and then decided to sit down and make a list of every single thing he had done that day with his hands — tasks and capabilities unique to his species.

Each Montessori lesson involving the concept of deep time is a particular blend of these same components. There’s the Timeline of Life, in a sense the opposite of the Black Strip — it’s crammed with pictures of the different forms of life inhabiting each geologic era up to our own. Then there is the Hand Chart, similar to the Black Strip but with one picture on it: a hand holding a stone tool. On the Hand Chart the black expanse represents, instead of geologic time, all of human history before the invention of writing, and the small red line at the end contains the Bible, the Bhagavad Gita, everything any of us has ever written. “Human beings have been busy,” says Fortun to her students, “using their intelligence, using their hands, transforming their environment, taking care of each other, telling their stories, for all this time before anybody wrote anything down.”

And there is the BCE/CE timeline that uses a string teachers pull on both ends, to show that time is going in both directions and we can at once learn about the past and imagine the future. The ends of the string are frayed to demonstrate that time is still going, always. Awes tells me that she once saw a group of children take out the BCE/CE timeline and proceed to organize themselves along it as the historical figures they were currently studying. “It was this ‘aha’ moment of, ‘Hey, you and I are living and working at the same time, but you guys are 800 years before.’”

Given the impressionistic nature of the lessons and the student-led response to them, I ask how exactly teachers can tell that the concepts are really sinking in. The response they all give is that the full results can take years to see. Fortun says that long after they’ve moved out of her classroom, students will put together a project that astounds her, and when she asks where they got the idea they will say, “Remember what you showed us in second grade?”

Children, it turns out, need time to process and incorporate these expansive ideas. “Something really deep and important is happening,” Awes says of the seemingly fallow periods that can follow these lessons, “we just might not know what it is. And that’s where the adult has to get out of the way of the child. We can be obstacles, because we don’t give children enough time to reflect.”

Seth Webb, Director of School Services at the National Center for Montessori in the Public Sector, echoes this sentiment. “What schools need to do to allow for these concepts to be rooted in the hearts and souls of kids is to give them the time to explore them. I mean, if you want an appreciation of deep time, you have to give them the time to appreciate it deeply.”

What strikes me most is the faith these teachers seem to have in their students. To wait on children in this way requires immense trust, especially in the high-stakes years of a child’s education. It’s an attitude that stands in sharp contrast to the anxious system I remember growing up, a system constantly requiring evidence that children are indeed learning everything they must know. The question, I suppose, is what we consider most essential in preparing children for the world we are going to hand them. In a Montessori framework, one of the most central interdisciplinary goals is for children to grasp what Dr. Montessori calls the Cosmic Task — something shared by animate and inanimate earth alike. Awes puts it this way: “Each organism and inanimate object has a dual purpose. One of the purposes is to do what they do for survival, but while doing that they're giving something back.” So plants, for instance, remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in order to survive. But in doing that, what they give back to the rest of us is oxygen. There are lessons called “the work of wind” and “the work of water.” The universe and the earth are presented as a system of interdependence, developed over billions of years and honed with immense specificity to create the conditions under which life exists. Children who understand this, who are exposed to it repeatedly and given time to contemplate it, Awes tells me, start to wonder what their own Cosmic Task might be, how they might support their community and their future, how they might give back.

But how many children are even given the opportunity to wonder in this way? Maria Montessori began her work with some of Rome’s most underprivileged children, but now, in the U.S. at least, Montessori education is often seen as something of an elite luxury. In a widely read 02022 New Yorker review of De Stefano’s biography on Montessori, Jessica Winter noted that “there are only a few hundred public Montessori schools in the U.S.,” and that the Montessori method has been “routed disproportionately to rich white kids.”

Sara Suchman, the Executive Director of the National Center for Montessori in the Public Sector, paints a very different picture of Montessori in contemporary public education. In 02022 there were around 200,000 students receiving a Montessori education in nearly 600 U.S. public schools, she says, and more than half of them are Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. In a letter to the editor challenging Winter’s review, Suchman wrote that “there is nothing inherent in a Montessori classroom or school that makes it the unique domain of the wealthy.”

What is certainly true of these public Montessori schools, however, is that they tend to almost always be choice schools — open to all students in a school district regardless of address, but with an enrollment cap that means only a certain number can be admitted. Suchman cites Mira Debs’ Diverse Families, Desirable Schools (02019) to explain that over time more white, higher-income families proactively work the system to place their children in such schools. This problem is beyond the scope of the Montessori model itself, though presumably not beyond the scope of education policy in general.

“When a single model is serving 200,000 students, that both shows accomplishment and also opportunity,” Suchman tells me. One of the reasons Montessori education is worth our advocacy, according to Suchman, is that it is the model that best takes into account both the present and the future. “Kids are human beings right now, in this moment, and they need a positive experience right now…but they also need to be prepared. A lot of other methodologies will do one or the other, but Montessori does them together.”

Making Montessori more publicly accessible and therefore available to children in a wider economic range is a challenge for many reasons, but one that Suchman highlights strikes directly at the allowance for deep contemplation: the tension introduced by yearly testing, and our expectation of seeing constant, steady, measurable improvement. We don’t want to wait, and Montessori classrooms — which are multi-generational and span three grades — tend to demonstrate a burst of gains in each third year. For instance, when schools test yearly they will often see a plateau through first and second grade in Montessori schools instead of steady progress, which can cause anxiety if allowances aren't made for the fact that third grade is when much of the progress will manifest.

Educators must be prepared to accept a certain amount of waiting, to take a longer view and give kids some time.

Even outside of more public schools transitioning to a full Montessori model, there are opportunities for some of these concepts and methodologies for teaching natural history to make their way into all kinds of classrooms. Seth Webb sees the current moment as an opportunity for pedagogical cross pollination: “There are really amazing teachers everywhere, regardless of the overarching pedagogical foundation. We’ve moved into a new era where our pedagogy would do well to collaborate more.”

Children who have been given the Great Lessons and the time to appreciate the interdependence of our environment, the fragility and specificity and particularity of circumstances that allow for our existence, who know what it took for the earth to “be ready” for us, might be just the kind of people that we need right now. According to the Clock of Eras, it’s been 14 seconds, and we don’t know how many seconds more we have. So what will we do?

Maria Montessori believed that she was working at the end of the Adult Epoch, and that what was coming was the Epoch of the Child. It’s unclear precisely what she had in mind with that terminology, but it seems to speak of a time when children who are treated with sufficient respect and given sufficient time and resources become adults and alter, on a large scale, the way we carry out our lives. Crucially, however, nothing new like this can be ushered in without decisions made now, by those of us who are not yet citizens of any of these new possibilities. A cosmic task for us, perhaps.

I can imagine what it might look like, rolled out in front of me. These brief years of our unprecedented technological dominion I imagine a pale, sickly yellow, the color of the fear so many of my generation seem to carry — the fear that we have gone too far. And at the end, slender but frayed at the edges to connote its expansion, a full, deep, blue-tinted black of possibility like a bare night sky, like a beginning.

After more than 26 years of dedicated service to The Long Now Foundation, Alexander Rose will be stepping down from his role as Executive Director to focus on The Clock of the Long Now, along with his research into the world’s longest-lived organizations. He will continue to serve on the Foundation’s Board of Directors.

For the past quarter century, Alexander Rose – known to his friends and colleagues simply as Zander – has been the engine behind so much of Long Now’s work. Under his leadership, The Long Now Foundation has gone from a fledgling nonprofit to a living, thriving organization, with a vibrant membership program, and twenty years of thought-provoking Talks. He also created The Interval, our combination cocktail bar, cafe, and gathering space in Fort Mason, San Francisco and is an active steward of The Clock of the Long Now.

Zander’s approach to guiding the Foundation has impacted every single one of us at Long Now. In order to properly commemorate his time here, we talked to the people he worked most closely with among Long Now’s staff, Board of Directors, and associates to paint a whole picture of Zander — as Long Now’s leader, but also as a friend and dedicated member of our community.

When The Long Now Foundation was still in a primordial state in the midst of the 01990s, its co-founders Stewart Brand, Danny Hillis, and Brian Eno ran the show. But as the Foundation grew and began to get to work on its core projects, it quickly became clear that Long Now needed a dedicated employee to manage The Clock and The Library. Stewart immediately sought out Zander, who he had known since Zander was just a kid in the junkyards and dockyards of Sausalito, California. Stewart served as “adult supervision” to paintball games and other adventures on the Sausalito waterfront, and to Stewart, Zander’s qualities as a “natural born leader” were clear from a young age. Kevin Kelly, another founding board member and denizen of the Sausalito waterfront, agreed, noting that even at a young age Zander was a tinkerer and skilled paintball tactician, “immediately trying to improve” the crude early paintball equipment and using it to “crush” Kevin, Stewart, and all other challengers.

When Stewart reached out to Zander more than a decade later, Zander, by then a recent graduate of Carnegie Mellon who was looking for work in the field of industrial design, was at first uncertain. As recounted in Whole Earth, John Markoff’s 02022 biography of Stewart Brand, Stewart also helped Zander get job interviews with a number of companies from the contemporary crop of San Francisco Bay Area technology startups. Yet even as he pursued those interviews, Zander couldn’t help but be captivated by the promise Long Now’s Clock and Library projects offered, even in a nascent form.

In the end, his home would be The Long Now Foundation, becoming the organization’s first full time employee and a general project manager, creative leader, and jack-of-all-trades in the Foundation’s early operations. From his first meeting with Zander, Danny Hillis was impressed by his “very practical sense of building things and getting them to work.”

The two would work closely together for years on the preliminary design and prototyping of The Clock of the Long Now. Zander provided a key understanding of, in Danny’s words, the “poetry and the philosophy of the Clock” from the very start. He was able to balance The Clock’s dual nature, holding it as “a machine to be engineered but, on the other hand, a story to be told.”

One early Clock design moment where Zander’s sensibility shone through was in the design of the Clock’s face. In Danny’s recollection, he brought a rough sketch of the astronomical lines he wanted depicted on the Clock’s face to Zander, who proceeded to turn it into the iconic rete design that still serves as part of Long Now’s brand to this day.

For the last few years of the 01990s, Danny, Zander, and a small team of collaborators worked tirelessly to get the prototype ready for their “very hard deadline”: New Years Eve 01999. Without Zander, Danny told us, they wouldn’t have made it:

“I brought my whole family up there and everyone at Long Now was gathered in the Presidio, where we were sharing a space with the Internet Archive. We had finally got all the pieces put together, but when we got them together, we realized that there was a bug in the direction of rotation of one shaft and that it was going to, when it hit the millennium, go from saying, oh, 01999 to 01998 instead of 02000 — the wrong direction.”

“So, there were hours to go before New Year's Day and we had been working on it and I had been traveling and I just said, ‘oh, well this is just kind of hopeless.’ And I actually fell asleep at that point because I was thinking ‘I don't know what's gonna happen, but I am exhausted.’ So I fell asleep. But then Zander figured it out. He realized that we could do it by just remachining one part and so he drove across to Sausalito. And by the time I woke up, Zander had remachined the part. And so when I actually came to midnight it was all put together and sure enough, at midnight it ticked forward and the dial clicked to the year 02000 and the beautiful chime that Zander had chosen, this beautiful Zen bowl chime rang twice. And so the clock chimed in the year 02000 with two bongs in perfect order.”

Zander’s work at Long Now, even in those early days, was not limited to The Clock. The Foundation’s core project has always involved building a cultural institution to deepen our understanding of long-term thinking in parallel to the Clock, and Zander dove into that cause with full commitment.

Along with a dedicated core of early colleagues, Zander helped develop a diverse set of projects that, in their ways, would help foster long-term thinking in the world. These projects included the Rosetta Project, a global collaboration of language specialists and native speakers that aims to preserve the world’s languages using long-term archival devices like microscopically etched disks, and Long Bets, our initiative for long-term predictions and wagers for charity.

Zander didn’t just help get these projects started; he has kept them running for decades as well. Andrew Warner, who has worked as a project manager in Long Now’s programs team for the last decade, says that Zander has “basically done every job at Long Now at some point,” from Clock designer to project manager to maintenance man. Earlier this year, Zander repaired a damaged hot water heater at the Long Now offices the same day he departed on a multi-week research trip on long-lived institutions in India. Throughout all those roles, Zander has maintained his unique sensibility and perspective on leadership. Former Long Now Director of Strategy Nicholas Paul Brysiewicz describes this perspective as a certain “pragmatism” that “does not suffer needless philosophizing.” Long-time Long Now Director of Programs Danielle Engelman cites Zander’s “clear decision-making process after weighing key options & opportunities” as having “kept Long Now's projects and programs moving forward at a pace that belied the small team working on them in the beginning.”

Over the years, Zander has also taken a lead role in one of Long Now's longest-running projects: our speaker series. Since 02020, Zander has acted as the host and co-curator for Long Now's main talk series, bringing together perspectives on long-term thinking from everyone from science fiction authors and artists to scientists, sociologists, and political leaders.

These projects, along with The Clock, helped build a mythos around the Foundation over the years. With this cultivated mythos came interest from the broader culture, with many around the world expressing interest in becoming more involved with Long Now’s work. In response, Zander worked to establish Long Now’s membership program in 02007. According to Danny Hillis, “he really led the idea of the membership program and supported Long Now members. And I think that the original board didn’t really see the potential of that the way that Zander did, but we trusted his intuition on that.”

As Long Now entered its adolescence as an organization, Zander began to research the world’s longest-lasting institutions — groups that had lasted for more than a millennium from businesses to religious orders. This project would later become Long Now's Organizational Continuity Project.

As he studied the records of these organizations, he began to notice a particular, unexpected commonality: across continents and cultural contexts, many of the longest-lived institutions were those that served and produced alcohol, from German breweries to Japanese Sake Houses.

For Zander, the obvious corollary to this finding was to open up a cocktail bar. At first, Long Now’s Board of Directors was skeptical. Running a bar is complicated, and a task far from the core competencies of Long Now at the time. As Andrew Warner put it, “Opening a successful bar is really hard and people didn't really ‘get it’ until it was done.”

But Long Now collectively put their trust in Zander, and he delivered. The Interval, which opened in 02013 after an extensive crowdfunding campaign was “pure Alexander,” per Stewart, with Zander’s fingerprint on everything: its “invention, funding, and peerless delivery.” Danny noted that Zander was especially adept at “getting all the permissions for getting things to happen at Fort Mason,” requiring Zander to use his “political finesse” to navigate the bureaucratic structures of working on federal property.

The Interval, which took the former space of Long Now’s museum and offices and turned it into a world-class cocktail bar, café, and gathering place, was thoroughly shaped by Zander’s influence. As Andrew recounted to us, he even “took the first doorman shift” for the bar’s opening day. Yet perhaps nothing about The Interval’s design speaks to Zander’s unique perspective more than the bar’s Gin Robot. As Nicholas Paul Brysiewicz describes it, “the gin robot at The Interval is the one thing I associate with Zander alone. It’s quintessentially his. It makes billions of gins. It lights up. The lights change color. The only ways it could be more Zandery would involve pyrotechnics.”

Over the past decade, The Interval has become more than just a place to get expertly-crafted cocktails and view the collection of Long Now’s Manual for Civilization. Under Zander’s supervision, the bar has become a place to tell — and to continue — Long Now’s story, a headquarters with a mythos all its own.

Zander’s time at Long Now did not, of course, keep him confined to our offices in Fort Mason in San Francisco. In Long Now’s early days, he traveled extensively with Danny, Stewart, and other board members to explore sites in the American southwest and beyond to find an eventual home for The Clock of The Long Now. As part of that process, Zander became an accomplished rock climber and cave explorer, venturing hundreds of feet into the depths of caves in Texas or mountains in Arizona.

Eventually, Long Now landed on a site at Mount Washington, on the border between Nevada and Utah in the Great Basin, as a likely choice for The Clock. Zander served as a de facto leader for the Long Now team as they explored the many crags and crevices of the mountain. As Danny recounted, “in dangerous situations it's always good to have somebody in charge who's making the decisions and Zander was the one to do that.”

After years of exploration of Mount Washington, Zander and the rest of the team thought they had found nearly all of the useful approaches and pathways within. Yet one particular entrance still eluded them. Inspired by the Siq, a narrow, shaft-like gorge that serves as the grand main entrance to the classical Nabatean city of Petra, Danny and Stewart had imagined a similar pathway as the main approach to The Clock. For years, they searched for it to no avail, until June 21, 02003.

On that day, Zander found a certain opening in what first seemed to Stewart and Danny, his travel companions, to be a “sheer cliff” face on the west side of the mountain. Zander found his way through that passage, a Class 4 crevice, ascending 600 feet alone. “Henceforth,” Stewart told Long Now, “it is known as Zander’s Siq.”

Once the potential sites for The Clock were identified, Zander’s travels did not stop. Instead, he took on a role as a kind of international ambassador for Long Now and for long-term thinking broadly. Those travels have taken him everywhere from the Svalbard seed bank and the far reaches of Siberia to the Hoover Dam, the 1400-year-old Ise Shrine in Japan, and the ancient stepwells of India.

Danny, who accompanied Zander on an early trip to Japan for the rebuilding of the Ise Shrine, which has occurred every 20 years since 00692 CE, recounted that the two of them had been two of the few westerners invited to the rededication ceremony, and the “amazingly moving” feeling of being there with Zander. Afterwards, the Long Now traveling party went to one of the area’s “bottle keep” bars, where patrons can leave part of a liquor bottle reserved for future use for an indefinite period of time. Zander explained to the bartender that Long Now would be returning to the bar in twenty years — in time for the next rebuilding of the shrine. While the bartender was at first skeptical, Zander managed to convince him that they’d actually be back — spreading the word about Long Now along the way. That encounter also ended up inspiring Zander to create The Interval’s own bottle keep system, which can, of course, be used more frequently than once every two decades.

While 02023 marks the end of Zander’s time as Long Now’s Executive Director, his work with us is far from over. He will continue his work on The Clock of the Long Now as its installation continues. He will also continue to work on the Organizational Continuity Project, discovering the lessons behind the world’s long-lived institutions and pulling these lessons into a first of its kind book. He will also continue to be a dedicated member of Long Now’s community, a vital part of the culture that he has fostered over the last quarter century as we go into our next quarter century. Thank you, Zander.

In his Histories, Herodotus tells the story of Croesus, a wealthy king who ruled the region of Lydia some 2,500 years ago. One day, Croesus consulted the famous oracle at Delphi about his conflict with the neighboring Persians. The oracle responded that if Croesus went to war, he would destroy a great empire. Sure of victory, Croesus marched for battle. Much to his surprise, however, he lost. The great empire he destroyed was not his enemies’, but his own. A few centuries later, the Persians were in turn bested by Alexander the Great.

Civilizations rise and fall, sometimes at the stroke of a sword. Myriad explanations have been posited as to why this happens. Often, hypotheses of collapse say more about the preoccupations of contemporary society than they do about the past. It is no coincidence that Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (01776), written during the anticlerical Age of Reason, blamed Christianity for Rome’s downfall, just as it is no coincidence that recent popular accounts of civilizational collapse such as Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (02005) point toward environmental damage and climate change as the main culprits.

I’ve been fascinated by the oscillations of human societies ever since the early days of my research for my Ph.D. in archaeology. Over the last 12,000 years, we’ve gone from small hunter-gatherer groups to highly urbanized communities and industrialized nation-states in a globally interconnected world. As societies grow, they expand in territory, produce economic growth, technological innovation, and social stratification. How does this happen, and why? And is collapse inevitable? The answers provided by archeology were unsatisfying. So I looked elsewhere.

Ultimately, I settled on a radically different framework to explore these questions: the field of complexity theory. Emerging from profound cross-disciplinary frustrations with reductionism, complexity theory aims to understand the properties and behavior of complex systems (including the human brain, ecosystems, cities and societies) through the exploration of their generative patterns, dynamics, and interactions.

In what follows, I’ll share some thoughts about what social complexity is, how it develops, and why it provides a more comprehensive account of societal change than the traditional evolutionary approaches that permeate archeology. By recasting the rise and fall of civilizations in terms of social complexity, we can better understand not only the past of human societies, but their possible futures as well.

In the 19th century, scholars like the sociologist Herbert Spencer and anthropologist Lewis Morgan became interested in the historical development of societies. They found a suitable explanatory framework in the principles of biological evolution as posited by Charles Darwin. Social evolution holds that human groups undergo directed processes of change driven by fitness adaptations to external circumstances, resulting in an inherent tendency to increase complexity over time. The phrase “survival of the fittest,” often attributed to Darwin, was coined by Herbert Spencer to describe the evolutionary struggles of societies. Social evolutionists conceptualized historical change as part of a teleological trajectory towards higher stages of social complexity. They believed complex societies to be the most successful. “Complex” entailed more developed rationality, philosophy, and morality. It meant, in short, more civilized. This notion of successful societies was appropriated and embedded in a wider framework of Eurocentrism and Western superiority to place Western nation-states at the pinnacle of human evolution and to provide a justification for colonialism (Morris, 02013, p.2).

During the second half of the 20th century, a neo-evolutionary resurgence resulted in the postulation of societal stages of development that are still in vogue today, such as Elman Service’s scheme of bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states (Service, 01962). While these works abandoned teleological notions, the identification of distinct developmental stages implies that fundamental properties co-occur in societies across time and space. It also suggests that societies stay in equilibrium until they go through a sudden phase shift and rapidly adopt a new set of properties and characteristics.

These assumptions are problematic in two ways. First, societal properties do not necessarily co-evolve, even if societal trajectories can converge to varying degrees due to similar underlying drivers (Auban, Martin and Barton, 02013, p.34). Second, equilibrium-based approaches are inherently static because they assume that changes cancel each other out over the long term. As a result, they regard change as ‘‘noise’’ that must be filtered out to understand the system. These approaches frequently employ reductionist views. This means identifying distinct subsystems, figuring out how these subsystems work, and then aggregating them to understand the behavior of the overall system. In human societies, that could mean identifying a separate economic system, then setting forth to understand that economy, while doing the same for other subsystems like politics, religion, and so on. Finally, by combining the understanding of each subsystem, we come to an understanding of society as a whole. Such top-down, reductionist approaches have strong limitations, as system behavior is not the result of the aggregation of the properties of its components, but rather the result of entirely new properties emerging in a bottom-up fashion. In other words, we must realize that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.”

Since the 01970s, scholars from a broad range of disciplines, including biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, systems theory and cybernetics, have been grappling with non-linearity, feedback loops, and adaptation across many kinds of systems, giving rise to the new field of complexity theory. Complex systems thinking posits that the fundamental units of social systems are social interactions between people. These interactions generate complex behavior, information processing, adaptation, and non-linear emergence. This means that social complexity is an inherent characteristic of all human societies, not just complex ones.

All human societies need energy and resources to sustain themselves. Beyond these so-called endosomatic needs, societies also have exosomatic needs, that is, energy requirements for material and technological maintenance and development. The social structures necessary for the exploitation of energy and resources can only emerge through the exchange and processing of information for communication, maintaining social connections, sharing knowledge, enabling innovation, and coordinating activities.

I assess social complexity through three main flows:

I define social complexity as the extent to which a social entity can exploit, process and consume flows of energy, resources and information (Daems, 02021). A society is not more complex because it is more civilized, but because it extracts more energy and resources from its environment or transmits information more efficiently. With this definition, complexity is dissociated from both social and environmental sustainability. Societies that manage to extract more energy and resources are not necessarily sustainable. Nor does enhanced information transmission always benefit society, as is so clearly illustrated in today’s struggles with misinformation.

This approach provides a clear answer to what social complexity is, but does not yet explain how it develops. Authors such as Joseph Tainter have posited social complexity as a problem-solving tool (Tainter, 01996). Societies are continuously faced with selection pressures – e.g. subsistence, cooperation, competition, production, demography, etc. – that act as input information for decision-making strategies driving societal development on two levels (Cioffi-Revilla, 02005):

Let us take the example of a society faced with a bad harvest. Such a society needs to assess the causes of this situation and define its strategies accordingly. Did the failed harvest stem from bad luck? Crop disease? The wrath of the gods?

Once the situation is assessed, a proper strategy needs to be devised. Do they try again and hope for the best? Experiment with new types of crops? Perform the necessary rituals to appease the wronged gods? Or perhaps they appoint officials to monitor agricultural production. Some strategies can be one-offs, such as a sacrifice or an official inspection. Or they can persist and become entrenched in the social fabric, such as when divine favor becomes indispensable for ensuring successful harvests, or a central government extends its control through a new bureaucratic system. Social structures do not spring forth fully-fledged from one day to the next, but are the result of incremental expansion, addition, and recombination of the outcomes of day-to-day decision-making processes.