Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

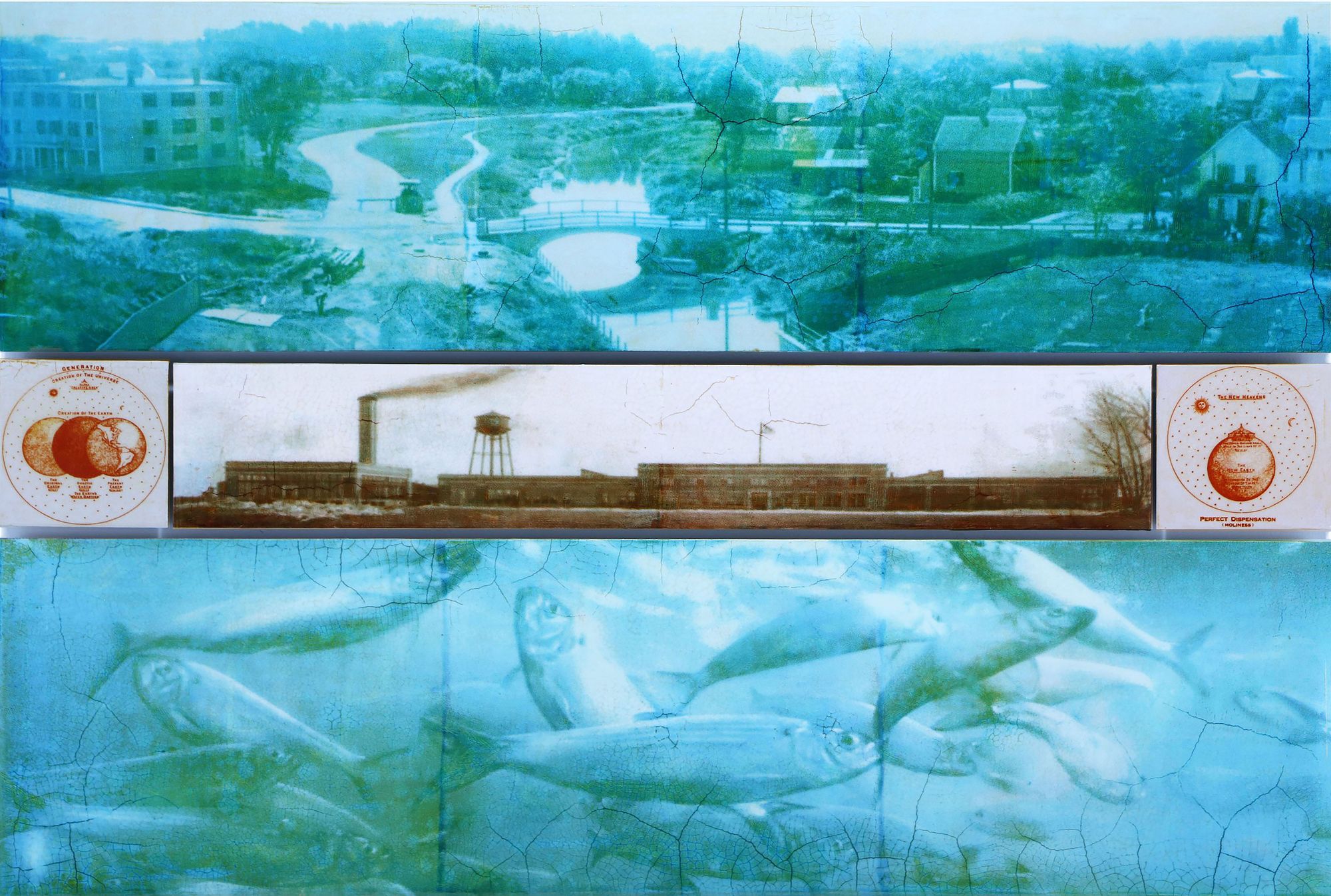

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

Big trees, old trees, and especially big old trees have always been objects of reverence. From Athena’s sacred olive on the Acropolis to the unmistakable ginkgo leaf prevalent in Japanese art and fashion during the Edo period, our profound admiration for slow plants spans time and place as well as cultures and religions. At the same time, the utilization and indeed the desecration of ancient trees is a common feature of history. In the modern period, the American West, more than any other region, witnessed contradictory efforts to destroy and protect ancient conifers. Historian Jared Farmer reflects on our long-term relationships with long-lived trees, and considers the future of oldness on a rapidly changing planet.

Join us for a thought-provoking conversation between two Hugo award-winning science fiction authors, Becky Chambers and Annalee Newitz. Known for challenging classic science fiction tropes such as war, violence, and colonialism, both authors create vivid and immersive worlds that are filled with non-human persons, peace, and a subtle sense of hope. The authors will discuss what it means to take these alternative themes seriously, delve into their writing & world building process, and explore how science fiction can help us imagine new futures that can make sense of our current civilizational struggles.

Doors are at 6pm; drinks & small plates are available to purchase. Club Fugazi will remain open and serving drinks after the talk, for further conversation. You can also tune in to the livestream on this page and our YouTube channel.

How can we turn the tide on species loss and help biodiversity and bioabundance flourish for millennia to come?

Ryan Phelan is Executive Director of Revive & Restore; the leading wildlife conservation organization promoting the incorporation of biotechnologies into standard conservation practice. Phelan will share the new Genetic Rescue Toolkit for conservation – a suite of biotechnology tools and conservation applications that offer hope and a path to recovery for threatened species. In this talk, Phelan will present examples of the toolkit in action, including corals that better withstand rising ocean temperatures, trees that withstand a fungal blight, and the genetic rescue of the black-footed ferret, once thought to be extinct.

Revive & Restore brings biotechnologies to conservation in responsible ways; from engaging local communities where ecological restorations are underway, to connecting stakeholders in disciplines like biotech, bioethics, conservation organizations and government agencies. Together, they are forging new paths to bioabundance in our changing world.

Ryan Phelan will be joined by forecaster and Long Now Board Member Paul Saffo for the Q&A to discuss long-term outcomes and the Intended Consequences framing used by Revive & Restore.

Looking for vicuña is not for the faint of heart, or for those who suffer from car or altitude sickness. After two hours of bouncing along rough dirt roads in an all-wheel drive pickup, I finally spotted a vicuña drinking from a pond at about 17,000 feet above sea level. Then I saw another, and another. Once I knew how to look, the hillside was suddenly spotted with vicuña. Their pale cinnamon backs and white bellies blended in perfectly with the harsh rocky landscape.

The vicuña is the baby-faced, shy cousin of the llama. Their eyes are almost comically large in their delicate faces, with long eyelashes. They are famously shy and run like the wind from any perceived threat. They also have some of the softest fur in the world. That fur earned them a prominent place among the Inca’s pantheon of sacred animals. It’s also what also makes them so valuable today.

The finest natural fiber, vicuña fur is a mere nine to twelve microns in diameter. For comparison, cashmere ranges from fourteen to nineteen microns. Each delicate strand is hollow, making it incredibly lightweight and insulating.

Vicuña fur is also difficult to find. Very few companies make garments with vicuña, and they sell to a select few stores. Though the fur comes from Peru, most of what you’ll find in a shop is made in Italy. Only one brand, Kuna, sells products made in Peru. Regardless of where it’s made, a simple scarf costs $1,000 to $3,000 USD, and a full shawl can cost upwards of $10,000 USD. Each garment is sold with a certificate, showing that the fur was harvested ethically in government regulated shearings of wild vicuñas.

Vicuña fur was exceptionally valuable long before Italian manufacturing. The Inca, who ruled much of South America in the 01400s and 01500s, decreed that only the royal family could wear vicuña fur. Vicuñas were both sacred and protected: hunting one was punishable by death. Despite the Inca’s attachment to the vicuña, they were never domesticated. Thousands of years ago, humans domesticated llamas and alpacas, but the vicuña stayed wild.

During Incan times, the protection afforded the vicuña helped it thrive. When the Spanish arrived in South America, they estimated that about 2 million lived throughout the Andes. That is when the indiscriminate killing of vicuñas began, which decimated the population.

When the Inca lost control of South America, the vicuña lost its protection. In the late 01500s, hunting vicuña went from being a capital crime to being encouraged by the Spanish crown. Change started in 01777, when the Spanish Imperial Court decreed it was illegal to kill a vicuña. Simón Bolívar enacted a similar law in 01825. Neither effort had much effect, and poaching continued. In the 01960s, about 2,000 vicuña remained in Peru, and only 6,000 in all of South America.

In 01969, Peru and Bolivia signed an accord in La Paz that began a new era of protection for the vicuña. Chile and Ecuador joined soon after, followed by Argentina in 01971. After 01969, the population quickly began to recover. A census conducted by Peru’s Ministry of Agriculture in 02012 revealed over 200,000 vicuña in Peru. Convenio de la Vicuña found over 470,000 in all of South America in 02016.

Why were conservation efforts in the 01970s successful when similar laws had failed for the previous 200 years? One likely explanation is who controlled the lands where the vicuña live. Land grants from the Spanish crown to colonizers in the 01600s took control of the lands away from Indigenous Andeans. Even after independence, Peru’s rural areas suffered under a feudal system where Indigenous peoples worked as unpaid serfs, in conditions akin to modern slavery. It wasn’t until the Agrarian Reform in 01969 that Indigenous communities started to regain control of their lands. Ownership of large tracts of land passed from the descendants of Spanish colonizers to the Indigenous communities who live on them.

Today, most land in Peru’s puna, the high altitude plateau that covers much of southern Peru, is communally owned by rural Indigenous communities, though some is privately owned. According to Santiago Paredes, director of Pampas Galeras National Reserve, regardless of who owns the land, all vicuña must be protected. Any community, person or company that owns vicuña habitat must register a management plan with SERFOR, Peru’s National Forest and Wildlife Service. The plans include specific ways that vicuña will be protected from poaching, as well as how their habitat will be conserved and, if possible, improved.

Even with the population rebounding, vicuñas are still at risk. The biggest threats to their survival are loss of habitat due to climate change, competition for grazing with domestic animals, diseases like mange, and poaching.

Climate models predict decreasing rainfall in the central and southern mountain ranges in Peru, which is precisely where vicuñas live. According to USAID’s Climate Risk Profile for Peru, “temperature increases are forcing lower-elevation ecosystems to move higher, encroaching upon endemic species and ecosystems and increasing risk of extinction of high-mountain species.” As climate change pushes vicuña higher up the peaks, their habitat shrinks and fragments.

It is legal to graze livestock on vicuña habitat, which decreases their food supply. Contact with domesticated animals and rising temperatures may be causing the increasing mange outbreak among vicuña. While more research is needed, a 02021 study in Peru found that 6.1% of vicuña surveyed were infected. The parasite not only saps the animal’s energy, it destroys their fur, which makes them vulnerable to the extreme cold of the Andes. Mange is now the leading cause of death in vicuñas.

Some of these threats are easier to manage than others. In 02022, Peru’s National Agrarian Health Service (SENASA) began treating vicuña for mange in eleven regions. Enforcement of anti-poaching laws is improving. The nebulous threat of climate change is much harder to combat. Communities now focus on protecting the vicuña’s habitat, hoping that their efforts to improve the vicuña’s food and water supply will compensate for the damages of climate change.

The most important aspects of vicuña habitat are a constant source of water, native grasses for grazing, and an absence of human development. Unlike most camelids, vicuña must drink water every day. They are territorial animals and live in small herds with one alpha male and up to ten females with their offspring. During the day, they spread out in grassy meadows to graze. At night, they climb up rocky hillsides to sleep on bare slopes where predators, such as puma, don’t have enough cover to get close.

All of this makes harvesting their fur quite complicated. Centuries ago, Andean civilizations developed the chaccu, a ritual gathering of vicuña herds to shear the fur before releasing the animals to the wild. In the 01990s, the population had grown enough to bring back the ancient tradition.

During a chaccu, people spread out in a loose circle up to a mile from a vicuña herd. They close in slowly, clapping their hands and making noise to concentrate the vicuñas in the center of the circle. Small chaccus may capture a dozen animals in one day, while larger ones can capture hundreds over a few days.

Today, chaccu isn’t exactly the same as it was five hundred years ago. An Incan ruler no longer presides over the ceremony. Communities now have trucks to drive out into the puna to get close to vicuña herds, trips that would previously have taken days or even weeks on foot. Shearing is now done quickly, with electric shears. Also, the fur is no longer kept for the royal family. It’s sold to international companies, many of which export it to Italy.

Chaccu organizers register the date and location with their local government. Three government officials plus a veterinarian oversee each event and ensure that all vicuña protection protocols are followed correctly. SENASA’s plan to treat vicuña for mange relies on chaccu.

Veterinarian Óscar Áragon has worked with vicuña for years and comes from a family that has raised alpaca for at least six generations. He has a master’s degree in South American camelids from the National Altiplano University in Puno, Peru.

“There are three steps to a modern chaccu,” Áragon explains. “When a vicuña is caught, the veterinarian first checks it for disease and draws blood samples. If it is sick, it’s treated. If not, it’s sent to the second stage, where somebody checks the length of the fur. It must be at least seven centimeters long so they can shear off five centimeters. It takes two or three years for their fur to grow that long. If the fur is long enough, then the animal is taken to the shearing station.”

In the early 02000s, a kilo of uncleaned vicuña fur could sell for as much as $600 USD. According to biologist Felix de la Cruz Huamani, the price has been dropping steadily since, which could pose a threat to this ancestral practice. A large chaccu takes hundreds of people several days’ of work to carry out. Most communities hold chaccu as a cultural tradition and use the money they earn from selling the fur to subsidize the event.

As the price of vicuña fur plummets, some communities have started to appeal to the Peruvian government for help, asking for funding to continue holding chaccus. Ongoing political chaos in Peru has hampered efforts to get needed support from the government. If the government won’t help, the second line of defense is tourism.

In 02022, two communities in the north of the Ayacucho region, Ocros and Santa Cruz de Hospicio, invited tourists to participate in chaccu. Armando Pariona Antonio grew up in Ayacucho and has worked with vicuña for over fifteen years. He created the company Vicunga Travel, named for the scientific name of the vicuña, to bring tourists to communities in Ayacucho. There are a lot of challenges, he says, to making chaccu a tourist activity.

“They hold chaccus wherever the vicuña are, and that’s always a remote place at high altitude. Also, communities need a lot of training on how to work with tourists.” Despite the challenges, Pariona Antonio is determined to help communities continue the tradition.

Felix de la Cruz Huamani believes we can look at the challenge of protecting the vicuña from a different angle.

“Landowners who have a land management plan for vicuña are required to protect and improve the ecosystem as part of their commitment to protect the vicuña,” explained de la Cruz Huamani. “We know that the vicuña’s habitat is rich in water. If we focus on the benefits of the ecosystem, we see that cities in Peru all depend on the water that comes from the vicuña’s habitat.” As the climate changes and water becomes more scarce, focusing national attention on the conservation of the vicuña’s habitat as a water source may have a bigger impact on protecting the vicuña than tourism or selling fur.

Peru’s environmental goals for 02030 include strategies for improving species conservation and reducing ecosystem damage. However, political instability is a significant challenge in meeting these targets. The Ministry of Environment, which is responsible for the 02030 goals, had four different ministers in 02022.

In the end, what is most likely to save the vicuña from all the threats it faces is its strong cultural bond with Indigenous Andeans. Now that they have reestablished the tradition of chaccu, communities that coexist with wild vicuña are determined to not lose the practice again.

“Nowhere else in the world do people have this kind of interaction with wild animals,” Pariona Antonio said. “It is a unique practice that comes to us from our Wari ancestors, the civilization that was in Ayacucho before the Inca conquered them.”

Peru’s Indigenous Andeans who honor their ancestral traditions may be the vicuña’s best bet for survival.

The comments sections of Dr. Peter Neff’s TikToks are filled with this sort of stuff. He’s a glaciologist and ice scientist, stationed in Antarctica over the summer and conducting vital experiments on Antarctica’s vast ice sheets and glaciers. He responds to many of these comments with humor. At the same time, he doesn’t give them too much thought.

“[My videos] are more just to show people the reality, rather than actually address the ridiculous conspiracy theories,” Neff told me, calling from McMurdo Station on the tail end of his field season in Antarctica. “They don't really deserve much air in my mind.”

The “ice wall,” or the idea that Antarctica is not a continent at the bottom of the globe but really a wall that circumscribes the Flat Earth, is a common refrain; as is the concept that “nobody is allowed” to go to Antarctica: that “they” (shady government agents) will prevent anyone from visiting, in order to keep whatever lies behind the ice wall hidden.

At the turn of the 20th century, Antarctica was still largely unknown. As Apsley Cherry-Garrard observed in the introduction to his classic book The Worst Journey In The World (01922): “Even now the Antarctic is to the rest of the earth as the Abode of the Gods was to the ancient Chaldees, a precipitous and mammoth land lying far beyond the seas which encircled man’s habitation.” But despite the hundred-plus years of exploration, habitation, and documentation since then, Antarctica remains utterly Other. It’s far away, it’s unlike anywhere else on the planet, and most people will never go there. They’ll only see pictures, and watch classic films like The Thing (01982) which project an image of peril and isolation onto the public consciousness.

Where gaps in public knowledge exist, conspiracies spring into life. Any post by a scientist or public figure about Antarctica will inevitably rack up comments accusing the original poster of “hiding” something, or of working for the government. Today’s landscape of Antarctic conspiracies is a tangled web — comprising everything from AI-generated Lovecraftian images purporting to be from turn-of-the-century expeditions, Nazis and UFOs, global warming denial, and flat-earthery. It’s a locus of conspiratorial thinking from all corners of the political compass, all converging, like lines of longitude, on the ice.

These sentiments might seem strange, but they're just the latest in a long history of projecting fantasies onto the southern continent. While the Arctic, thanks to its relative proximity to seafaring civilizations, was explored beginning in the Age of Discovery in the 01500s, the terra australis incognito at the bottom of the earth remained mysterious for far longer. The circumnavigations of Captain Cook in the 01770s proved that the area was frozen and uninhabitable, and fringed by seemingly impenetrable pack-ice. The reports that he brought back probably inspired Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner (01798), which launched tropes of the frigid Antarctic into the wider cultural consciousness.

The southern continent itself was not observed until the 01820s, when adventurous whaling captains spotted it and added it to their charts. The simultaneous voyages of Ross (Britain), D’Urville (France), and Wilkes (USA) in 01839 added much to the world’s stock of knowledge of the Antarctic, but after that, investigation did not resume for over 50 years. When the North’s mysteries ceased to hold appeal, the world’s attention turned south to the Antarctic in the 01890s. Suddenly the region seemed to hold immense promise for scientific investigation, the claiming of new territories, and perhaps even the exploitation of mineral resources. The ensuing openly imperial Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration segued into the slightly more covert geopolitical jockeying of the mid-20th century. This reached a fever pitch with the International Geophysical Year of 01957-58, resulting in the Antarctic Treaty of 01959, which officially demilitarized the continent and set it aside as the exclusive preserve of scientific activity.

Many of the favored points for conspiracists have to do with government and military operations during this Cold War era. Neff points out the importance of the military presence on Antarctica, specifically the US military: “Their ability to operate their logistical capabilities are what give us the greatest scientific capability in Antarctica of basically any country.”

Despite Antarctica being “the continent of science,” with all military operations being banned since the Antarctic Treaty of 01959, the ongoing game of international geopolitics forms the underlying purpose of activity in the region. While military activity qua activity is verboten, it is the planes and personnel of various militaries which provide the structural capacity for people to live and work there.

Sara Wheeler, in her transformational Antarctic travel book Terra Incognita (01996), succinctly defines that paradox: “Collective consciousness must believe in the deification of science on the ice, otherwise it would have to admit that the reason for each nation’s presence in Antarctica is political, not scientific.”

That isn’t to say the vital climatic science done on Antarctica is in any way false or tainted. Scientists like Neff just want to be transparent about how it is they get to do the things they do, and go to the places they go. “It’s so hard to access these places, and the best way to get to them from a science perspective is through organized government programs,” he says. The mantling of the truth, though, is something that perhaps the conspiracists can sense, but are unable to understand or articulate, and so seek explanation in the outlandish. So the communal cooperative fantasy fails, and through the cracks come the crackpots.

A great deal of Antarctic theories, whether their proponents are aware of it or not, have roots in the original polar conspiracy of John Cleve Symmes Jr. Symmes was a US Army officer from Cincinnati who devoted his life to promoting his theory of the “hollow earth.” His claims changed over time, but the central thrust of the idea was that the earth was a hollow shell 800 miles thick, with thousand-mile-wide openings at both of the poles, through which a fertile interior could be accessed by intrepid explorers. In the late 01810s he confined his ideas to privately printed circulars and pamphlets, but by 01820 had begun lecturing around the country. He became somewhat well known, with his theories gaining traction after publication in outlets like the National Intelligencer; and it was his disciple Joshua Reynolds who helped drum up government support to launch the Wilkes Exploring Expedition of 01839, America’s first official venture to Antarctica.

The presence of Symmes’s theories in the public consciousness is visible in Edgar Allan Poe’s novella The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (01838), in which the titular character is carried in an open boat below the Antarctic Circle to a tropical land populated by dark-skinned subhumans, and thence to a frigid whirlpool at the North Pole, seemingly leading to some kind of mysterious interior space, inhabited by a giant shrouded figure: “And the hue of the skin of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.”

The desire for polar and Antarctic space to be indeterminate and undiscovered, for something beyond human understanding to be hiding underneath or within the ice, is a common underlying feature to Antarctic conspiracies.

In the mid-20th century, after the fervor of the Heroic Age of Shackleton and Scott died down, and the old school of isolated cross-continental man-hauling through ice and wind had been made obsolete by motors, planes, and radios, it was the Antarctic flights of Richard Byrd that captured the world’s imagination. Byrd, a decorated officer in the US Navy, was a pioneer of early flight. He claimed to be the first person to fly over the North Pole in 01926 (though that claim has since been disputed, thanks to evidence belatedly discovered in Byrd’s diary) and led five separate expeditions to the Antarctic from the 01920s through the 01950s. While the first two of these expeditions were independent, the latter three were conducted by the US government. Operation Highjump, the 01946-7 expedition led by Byrd, established a research base on the Ross Ice Shelf known as Little America IV; and Operation Deep Freeze of the 01950s under his direction was a massive operation which saw the first permanent American bases being constructed at McMurdo and the South Pole by Navy Seabees.

These expeditions, and Byrd himself, form the nucleus of a galaxy of conspiracies. The comments section of a newsreel video about Byrd’s explorations are filled to the brim with assertions about what he “really” saw down there. In the Ancient Aliens segment about Byrd’s “discoveries,” one common version of the tale is described, ostensibly recorded in a recently-recovered “lost diary.” Byrd, on his flight over the continent, enters a fertile hollow earth and meets a race of UFO-flying inhabitants who express disappointment in humanity’s recourse to nuclear power. Alternatively: he met and fought with Nazi-piloted flying saucers, which is why Operation Highjump necessitated such a large expeditionary force being brought back to Antarctica.

Nazis in Antarctica? Well, there’s a kernel of truth there. In 01939, the Third Reich sent an expedition to explore and claim part of Antarctica. The Schwabenland was equipped with planes, which dropped thousands and thousands of iron swastikas over the ice as they surveyed — none of which have ever been recovered.

The claim, in the remote sector of Dronning Maud Land already claimed by the Norwegians, was abandoned by the end of the war, but the concept of a Nazi base in the Antarctic lived on, messily pleated into the greater world of Antarctic conspiracy. Uncountable variations on the “Antarctic Nazis” myth have proliferated, including many versions in which Hitler and other senior Nazis did not die but sought shelter at an underground Antarctic base in New Schwabenland, and others that incorporate advanced Nazi technology in the form of UFOs and weapons.

On one of Neff’s TikToks, a commenter pleads: “The earth is hallow [sic], there’s entrances at the north and south pole where it suddenly gets warmer. if you can prove me wrong and go to the south pole could you try? i’ve been heavily convinced it’s hallow and it drives me crazy man [...]”

Being reduced to seeking confirmation of one’s conspiracy in the comments of a scientist is unfortunate. But it is also an example of how intoxicating the otherworldly potential of Antarctica is.

It may not be the location of the entrance to a hollow earth, but it is, in fact, hallow(ed). The only continent with no history of human habitation, the vast ice fields of Antarctica have formed a blank slate onto which humanity can project itself: all of itself, from the heroic, imperial superego to the conspiratorial id. It has attracted pilgrims and truth-seekers, scientists and artists, writers and soldiers.

Mapmakers of the early modern period placed monsters in the unknown corners of their charts: hic sunt dragones (“here be dragons”). The beasts were pushed further and further to the margins of the mappa mundi as the globe was explored, and eventually off the maps altogether, but the impulse to assign familiar, fire-breathing forms of danger and mystery to what would otherwise be unforgiving, cold, quiet places remain. The heated excitement of Antarctic conspiracies are the dragons of today.

[Read: Ahmed Kabil’s 02018 Long Now Ideas essay on early modern maps and the tendency for mapmakers to imagine monsters in uncharted regions]

Polar scholar Hester Blum, in her book The News At The Ends Of The Earth (02019), suggests that John Cleves Symmes’ conception of the hole at the bottom of the earth, the “polar verge,” with its five concentric spheres inside folding in on each other like a planetary Russian doll, is a fantasy about climactic extremities: a dream of impossible warmth and life where one would expect mundane cold and death.

So too, then, might be the fantasy of Byrd’s Symmesian discoveries, and the crystal cities and advanced beings inside the earth; or, as Joe Rogan associate Sam Tripoli frames it on an episode of Rogan’s popular podcast, “some time-traveling Nazi shit” involving a worldwide “spiritual war” centering on New Schwabenland. As the cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove puts it in Apollo's Eye (02001), “there seems to be an unwillingness to contemplate these global regions without anxiety.” In the face of endless reports of the Earth’s climactic demise issuing from Antarctic research, many might find it easier to believe that the official line of doom and gloom disguises awesome and awful spectacles of aliens, Nazis, and denizens of a hollow (or flat) earth.

And let’s not forget that Antarctica is the planet’s most concentrated record of deep time. It is, as many scholars have noted, an archive in and of itself, stretching back eons, documenting changes to Earth’s atmosphere going back long past the last ice age. Human activity on the continent constitutes barely the smallest sliver of that time — and only on the fringes of the coasts and at a few minimal inland stations. The vastness of Antarctica is untouched and implacable; difficult to comprehend from a limited human perspective. Like the Shoggoths and Old Ones which inhabit the ancient, abandoned Antarctic of Lovecraft’s imagination in “At The Mountains of Madness,” the continent itself is apt to induce a sort of insanity, even for those who are not physically present.

But of course, there are people at this moment trying to comprehend it more fully and objectively. Way out on the ice, at the remote Dome C location on the Antarctic Plateau, scientists are beginning a project to retrieve ice core samples that are over one million years old. It will take them five years to retrieve the oldest samples which lie miles down, against the bedrock of the continent, but scientists will begin to analyze samples right away, seeking evidence of atmospheric shifts in the distant past, which can then be used to predict those that are coming in the near future.

Neff, and other environmental scientists and educators, were recruited by TikTok during the pandemic to make educational content for the platform. He sees the broad channels afforded by social media as a vital tool for environmental awareness. “We’re trying to share useful information, to keep people's baseline understanding of climate change up, rather than trying to save the people who have just been terribly misled,” he says. He is tentatively excited about the possibilities for Starlink and other new connectivity technologies to help communicate the realities of the Antarctic to the public.

But as climate scientists and communicators know all too well, just because evidence is provided doesn’t mean people will believe it. The inextricability of Antarctic history and military history is always going to induce skepticism amongst those already primed to distrust the establishment. There will always be people who dream at a distance of a “polar verge” and the secrets lurking beyond it.

This event will take place the evenings of May 12th & May 13th at St. Joseph's Arts Society; there is one show each night, doors are at 7:00pm and the show starts at 8:00pm.

Arrive early, get a drink from the in-house bar and explore the intriguing installations at the St Joseph's Arts Society.

The Long Now Foundation has teamed up with Anthropocene Magazine (a publication of Future Earth) and Back Pocket Media to take the magazine’s new fiction series “The Climate Parables,” from the page to the stage.

The series starts with the idea that survival in the Anthropocene depends on upgrading not just our technology, but also our collective imagination. From there, acclaimed storytellers will perform work from some of the most creative science fiction writers such as Kim Stanley Robinson and Eliot Peper, speculating on what life could be like after we’ve actually mitigated climate change and adapted to chronic environmental stresses.

Think of it as climate reporting from the future. Tales of how we succeeded in harnessing new technology and science to work with nature, rather than against it. It’s all wrapped up in an evening of performed journalism that blends science and technology, fiction and non-fiction, video, art, and music. What could possibly go right?