In a decrepit house in São Paulo lives a woman who many people call a bruxa (the witch). As a blockbuster Brazilian podcast recently revealed, Margarida Maria Vicente de Azevedo Bonetti is wanted by U.S. authorities for her treatment of a maid named Hilda Rosa dos Santos, whom Margarida and her husband more or less enslaved in the Washington, D.C. area:

In early 1998—19 years after moving to the United States—dos Santos left the Bonettis, aided by a neighbor she’d befriended, Vicki Schneider. Schneider and others helped arrange for dos Santos to stay in a secret location, according to testimony Schneider later gave in court. (Schneider declined to be interviewed for this story.) The FBI and the Montgomery County adult services agency began a months-long investigation.

When social worker Annette Kerr arrived at the Bonetti home in April 1998—shortly after dos Santos had moved—she was stunned. She’d handled tough cases before, but this was different. Dos Santos lived in a chilly basement with a large hole in the floor covered by plywood. There was no toilet, Kerr, now retired, said in a recent interview, pausing often to regain her composure, tears welling in her eyes. (Renê Bonetti later acknowledged in court testimony that dos Santos lived in the basement, as well as confirmed that it had no toilet or shower and had a hole in the floor covered with plywood. He told jurors that dos Santos could have used an upstairs shower but chose not to do so.)

Dos Santos bathed using a metal tub that she would fill with water she hauled downstairs in a bucket from an upper floor, Kerr said, flipping through personal notes that she has kept all these years. Dos Santos slept on a cot with a thin mattress she supplemented with a discarded mat she’d scavenged in the woods. An upstairs refrigerator was locked so she could not open it.

“I couldn’t believe that would take place in the United States,” Kerr said.

During Kerr’s investigation, dos Santos recounted regular beatings she’d received from Margarida Bonetti, including being punched and slapped and having clumps of her hair pulled out and fingernails dug into her skin. She talked about hot soup being thrown in her face. Kerr learned that dos Santos had suffered a cut on her leg while cleaning up broken glass that was left untreated so long it festered and emitted a putrid smell.

She’d also lived for years with a tumor so large that doctors would later describe it variously as the size of a cantaloupe or a basketball. It turned out to be noncancerous.

She’d had “no voice” her whole life, Kerr concluded, “no rights.” Traumatized by her circumstances, dos Santos was “extremely passive” and “fearful,” Kerr said. Kerr had no doubt she was telling the truth. She was too timid to lie.

Guest post by Alexander Noyes

On May 17, the president of Ecuador, Guillermo Lasso, dissolved the country’s legislature in the midst of impeachment proceedings against him. Did Ecuador just have a self-coup? Opposition leaders say yes. But the answer is no, at least for now. This matters greatly for the country’s democratic trajectory and for the international community’s response.

After a recent lull, coups and coup attempts are front-page news again, from Sudan to Brazil to the United States. This surge in coup activity prompted Antonio Guterres, the United Nations chief, to decry an “epidemic” of coups. Perhaps more troublingly for democracy worldwide, coups-plotters have evolved. Scholars have traditionally defined coups as: “overt attempts by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting head of state using unconstitutional means.”

But now, these softer, more subtle self-coups—whereby a sitting chief executive uses sudden and irregular (i.e., illegal or unconstitutional) measures to seize power or dismantle checks and balances—have become the new mode of coup. Self-coups, also known as auto-coups, are much more sophisticated than soldiers in fatigues taking television stations by force in order to announce the overthrow of a country’s leader. Self-coups are rarely bloody, but can be just as harmful to democracy as the more traditional military overthrows.

A raft of countries have experienced successful self-coups or coup attempts of late. There have been nine successful or attempted self-coups over the last decade, according to the Cline Center at the University of Illinois, which collects comprehensive information on all types of coups around the world. Self-coup illegal power grabs have occurred across a range of regions and political systems, including in semi-autocracies, such as Pakistan in 2022, as well as semi-democracies, like Tunisia in 2021. Worryingly, full democracies have not been immune to this trend, with the United States suffering a failed self-coup at the hands of President Trump on January 6th, 2021, which the Cline Center labeled an auto-coup.

Ecuador has been lauded as a strong partner of the United States in a region that has experienced democratic backsliding. Yet the country has recently experienced a host of crises on Lasso’s watch, including rising crime, corruption scandals, government crackdowns on the media, and protests that have often turned violent. The current impasse is the opposition’s second attempt at impeachment.

Is Lasso’s dissolution of Ecuador’s National Assembly the latest example of a self-coup? Leonidas Iza Salazar, the head of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities, which has led a series of protests against the president over the last several years, says yes. On May 17, Iza Salazar accused Lasso of launching “a cowardly self-coup with the help of the police and the armed forces, without citizen support.” Viviana Veloz, the opposition lawmaker leading the impeachment, said: “The only way out is the impeachment and exit of the president of the republic, Guillermo Lasso.”

Lasso defended his decision as a chance at a fresh start and a way to resolve recent political turmoil. Lasso proclaimed that the dissolution was “the best decision to find a constitutional way out of the political crisis… and give the people of Ecuador the chance to decide their future at the next elections.” Lasso’s decree calls on the country’s electoral authorities to set a date for fresh elections, now set for August 20, and allows him to govern with limited powers and without the National Assembly until these new elections. The measure is referred to as a “mutual-death” clause, since it leads to new elections for both the sitting president as well as the legislature. Lasso has promised that he will not seek reelection in the coming polls.

There is little question that dissolving the legislature during his embezzlement impeachment trial and slumping political support is an opportunistic move by Lasso. Yet while Lasso’s action was indeed extraordinary—it is the first time this constitutional provision has been used since it was adopted in 2008—it is legal, at least so far. On May 18, the country’s constitutional court upheld the decision, dismissing six cases aimed at blocking the legislature’s dissolution. This means that Lasso’s maneuver does not yet fit the “irregular” provision that must be fulfilled to meet the definition of a coup, including a self-coup.

This “coup or not a coup” distinction matters greatly for Ecuador’s democratic future, and should guide how the international community responds. If Lasso’s action did indeed fit the worrying rise of self-coups globally, it would be dire for Ecuador’s prospects for democracy, and likely plunge it towards autocracy. International actors would need to condemn the coup, push for regional and global sanctions, and apply strong pressure to reverse Lasso’s illegal power grab.

Since Lasso’s decree is unusual but legal, Ecuador’s shaky democracy—which democracy watchers rate as falling short of a full democracy—is on precarious, but at least constitutional footing, for now.

At this precarious moment, the United States and other like-minded, pro-democracy countries should not sit idly by. While fully recognizing the country’s own struggles with incumbent power grabs, the United States should urge Lasso to strictly keep to the letter and spirit of the law, reign in the security forces—ensuring their political impartiality—and ramp up support to help Ecuador arrange free and fair elections in the coming months.

The role of the military along with unified international pressure has proved crucial to stopping or reversing past self-coups around the world. The current situation in Ecuador fortunately does not yet fit that definition. But the international community would be wise to actively keep it that way, first by strongly and consistently reminding Lasso—and other key regional partners—that the world is watching, and by also increasing democracy support to Ecuador ahead of the coming polls.

Alexander Noyes, PhD, is a political scientist at the non-profit, non-partisan RAND Corporation and former senior advisor in the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy.

While visiting the exhibition by the artist Xadalu Tupã Jekupé at the Museum of Indigenous Cultures in São Paulo, one of the works caught my attention. It was a monitor on the floor. On the screen was a modification of the game Free Fire, where it was possible to follow a virtual killing taking place from the point of view of an indigenous character wearing a headdress. For a while I couldn’t look away. I remembered a conversation I had with Anthony, a Guaraní-Mbyá professor that works with the youth of his territory. At the time I was also a teacher, working with marginalized youth. I remember Anthony’s distressed words—he was concerned about the time and attention young people were putting into games like Free Fire, creating a situation very similar to the one I lived when I worked with teenagers in the outskirts of São Paulo.

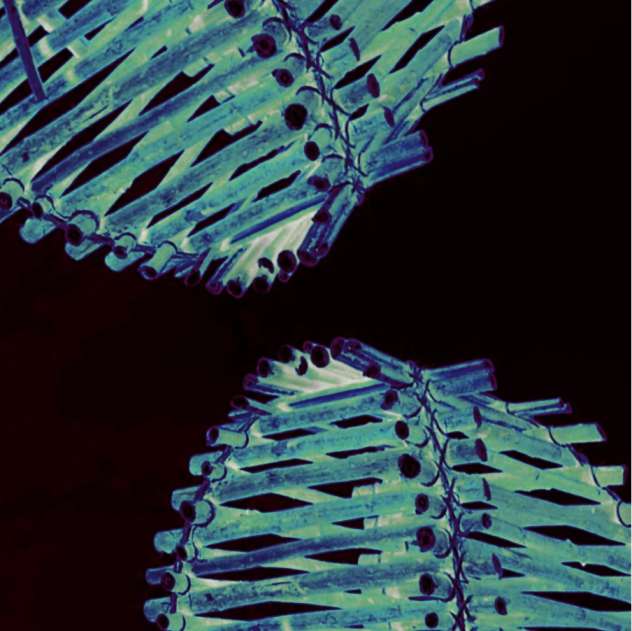

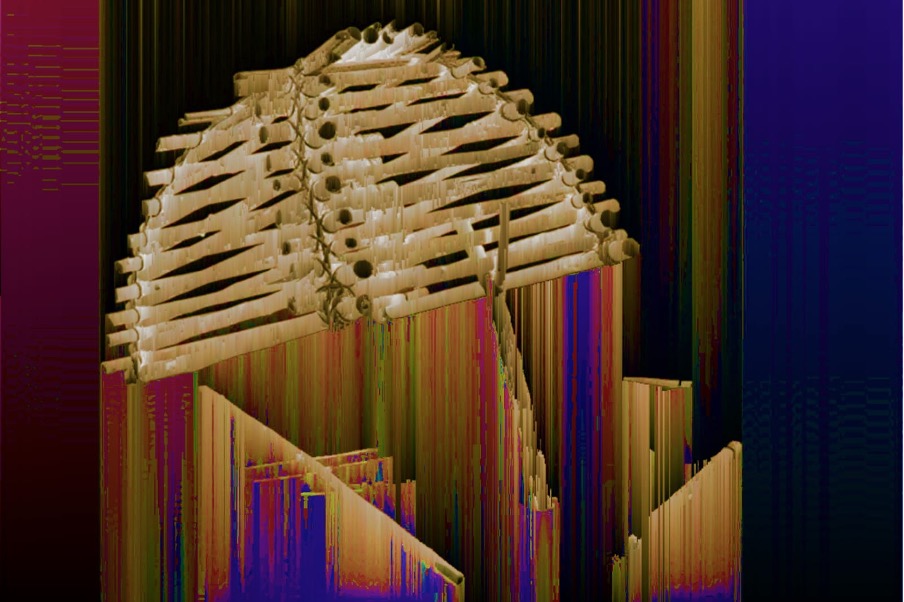

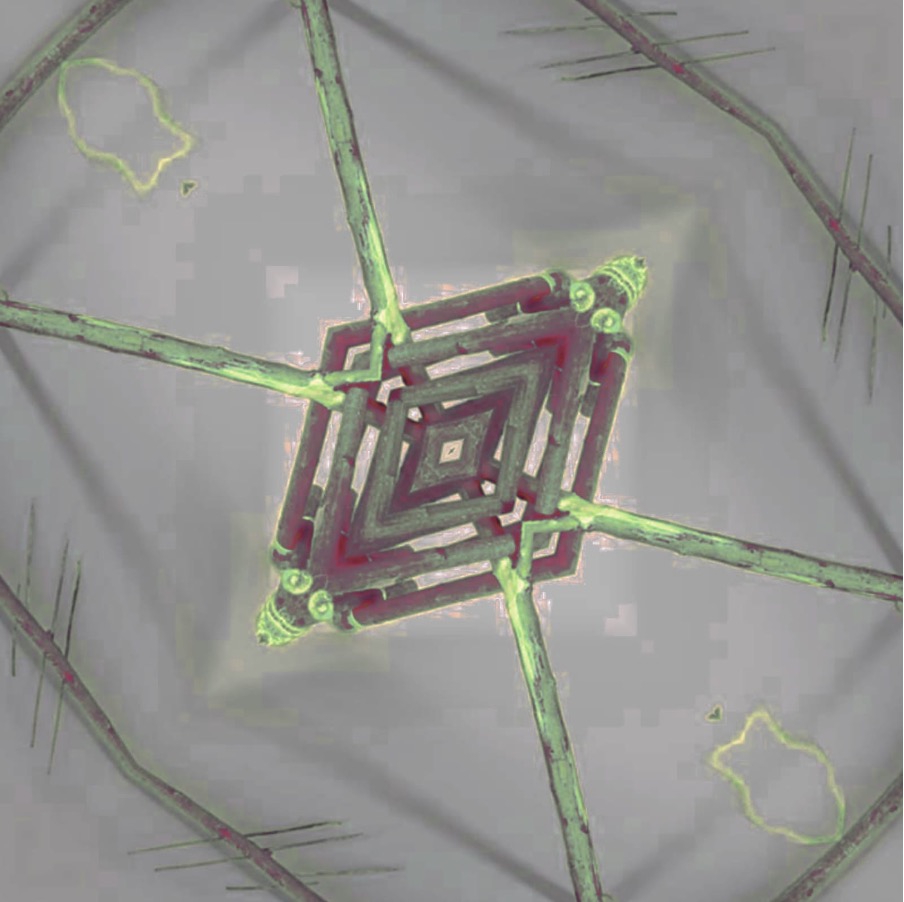

It took a while for me to get rid of the profusion of shots, bodies, and feathers that were frantically intertwining in front of the monitor. I took a few steps away from the work when my partner, who was with me at the exhibition, called my name. “Did you see it?” he asked me, pointing at the monitor. “I saw the Free Fire….” Smiling from the corner of his mouth, he said, “No, you didn’t see it… it’s a trap!” I thought to myself, yes, I know, it’s a trap. It took me a few seconds to realize that the monitor was positioned inside a beautiful bamboo structure, a kind of hollow basket in the shape of a pyramid, resting on one of the edges on the floor, with the opposite edge suspended by an ingenious system of capture made of joined pieces of bamboo. It was an arapuca, a traditional trap set to capture those who let themselves be seduced by the offer placed inside. A trap that captured me without even having the opportunity to resist.

This text is an outline of a proposal for a feminist and decolonial strategy to be and remain working and producing techno-scientific knowledge within academic institutions. I present the trap as such a strategy, a kind of low-intensity guerrilla technique so that we, marked bodies, can establish alliances and move within structures that are essentially bourgeois, masculine, and Western. This strategy is especially important for those of us who research with other scientists, or who have science and technology as the main focus of our concerns. It allows us to experiment with ways of researching that are simultaneously capable of carrying out the necessary denouncements while also experimenting with possible ways of production of techno-scientific knowledge that interests us.

In The Science Question in Feminism, Sandra Harding asks: “Is it possible to use for emancipatory ends sciences that are apparently so intimately involved in Western, bourgeois, and masculine projects?” (p. 9, 1986). In this way, Harding displaces the question of women in science from a concern with proportionality and representativeness and moves instead toward questioning the very structures of the production of techno-scientific knowledge. As a result of Harding’s provocations, Donna Haraway writes the article “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective” (1988), a classic of feminist studies of science and technology. Even today, a few decades after the article was first written, the questions raised serve as support for us to elaborate our thoughts in a scenario that is still structurally very similar to the one Harding described—bourgeois, masculine, western.

In the last two decades, the composition of the higher education body in Brazil has been changing through struggles that resulted in affirmative public policies, implemented by leftist governments from 2003 onwards. Some of these actions were: the construction of universities in peripheral regions of the country; the establishment of quotas in public university entrance exams for people coming from the public education system, black people, and indigenous people; and the funding of programs for people from the working classes to access private higher education. I myself am the result of this process, a worker daughter of workers. With this never-experienced-before entry into higher education by a greater diversity of people than ever before, the resumption and transmutation of the issues raised by Harding and Haraway is a necessary and effervescent movement, so that our occupation of these spaces does not end up swallowing ourselves in our differences. The institution is a machine for shaping bodies and homogenizing possibilities of futures.

Something we inevitably end up asking ourselves as marginalized people is whether we should occupy these spaces. Stengers (2015) addresses this issue, defending our permanence in spaces of contradiction, including the academy, as a way not to resolve this contradiction once and for all, but to at least get to know the terrain through which we are forced to walk—and, who knows, build new alliances capable of establishing other trails. If we want to remain researchers, teaching and working within universities, we need strategies to make our permanence viable. This obviously includes a constant struggle for better material conditions, but that goes hand-in-hand with the need to remain honest with our differences—which is only possible with a radical change in the way science is produced. It is necessary to cultivate techniques of insistence that, on the one hand, protect us and, on the other hand, allow us to continue walking and facing the overwhelming monster we are facing. Knowing how to produce traps can be one of these techniques.

An arapuca, a traditional trap (image made by Clarissa Reche)

“The nature of the trap is a function of the nature of the trapped.” It is in this way that Stafford Beer (1974) summarizes one of the most interesting attributes of the trap: the cybernetic character between the object, who designed it, and what it is intended to capture. These three nodes are entangled in a feedback system that works like a game of mirrors where, when we look at any of the nodes (capture-trap-captive), we will inevitably find the other nodes. In this game of mirrors, we can see not only the relationship of nodes with each other, but also with the environments they compose. The trap therefore participates in complex fields of interactions.

Anthropologist Alfred Gell (1996) sought in African traps a tool to think about the tension between the piece of art, specifically Western, and the artifact, arising from the so-called “exotic” cultures. Gell argues that the possible conciliation between these poles lies precisely in thinking of both as traps, in an exercise of horizontality that, in a single movement, empties Western arts of their specificity, filling them with ethnicity. The anthropologist makes an exquisite description of the conceptual modes of operation of a trap.

For Gell, the trap is the knowledge of oneself and the other turned into an object. The trap is a functional model of the one who created it, replacing the presence of the one through a “sensory transduction” (p. 27, 1996). The capturer’s senses are replaced by a set of “sensors” attached to the trap, such as a rope or a stick that can simultaneously sense and act as triggers. In this sense, the trap is an automaton. But, at the same time, it is a model of what one wants to capture, since in order to function it needs to emulate and incorporate behaviors, desires, tendencies, functioning as “lethal parodies of the umwelt” (own world) of the captive.

In addition to this spatial dimension, the trap also has a temporal dimension whose structure is based on waiting. In this way, the trap incorporates a scenario of a dramatic nexus between the capturer-captive poles. Gell describes this waiting as a tragic theater, where the trap places the captor and the captive in a hierarchy. The metaphor would be that who sets the trap is God, or fate, and who falls into the trap is the human being in his tragedy. The task of creating traps would therefore be to experiment with controlling fate. However, if we take into account Amerindian conceptions of the trap, such as the Guarani-Mbya practice/thought, this relationship becomes more complex, since a prey is only captured in the trap if there is consent from its owners, who are non-human entities responsible for the animals. Here, the attempt to control fate slips through the bamboo stakes—the tragedy is shared between captor and captive.

From an Amerindian perspective, in particular Guaraní, the trap can be understood as a “memory card” (Caceres and Sales, 2019) capable of storing information that accounts for a profusion of knowledge such as: the behavior of the prey in its environment, modes of production of traps, cosmopolitical relationships involved in hunting, etc. But this potential for keeping memory has been gaining other contours with the increasing destruction of nature and traditional ways of life. With indigenous peoples without possession of their territories and abandonment in the face of deforestation and land grabbing that agribusiness and mining advance, hunting is no longer a possible reality. The maintenance of traps in this scenario becomes a form of resistance, a way of safeguarding what is possible and transmitting that memory to those who are growing up and will soon be responsible for the struggle.

Returning to the idea of thinking about the trap as a strategy to be and remain producing techno-scientific knowledge within an academic context, I would like to list the following characteristics that may be useful to us:

Acquiring the necessary knowledge to build a trap also helps us to know how to identify one when we come across it on our walk. Stengers points out how a moment of relative success, when you move from a position of contestation to a position of an interested party, is also a dangerous moment. For many of us who insist on working at the university, coming from classes historically far from that space, life becomes restricted, in an eternal non-belonging. On the one hand, it shows the impossibility of “integration” into the ideal body of those who produce technoscience—we have no way of doing that. On the other hand, we are haunted by a constant (self-)accusation of betrayal, and in fact something is lost from our previous relationship with “our own.” Faced with this impasse, Stengers proposes that we be able to “foresee that there will be tension” (p. 89, 2015), that is, share common knowledge and experiences that help identify and avoid predictable traps.

Image of an arapuca, a traditional trap (image by Clarissa Reche)

Some traps of the scientific knowledge production system are quite obvious. We come across well-set traps that straddle the path as we advance along our academic careers. We see the trap and look around. The alternatives are to abandon the trail or to stay in the same place. Since the food is just inside the trap, standing still means starving, or at best surviving in starvation. If we want to insist on the journey, we must voluntarily surrender ourselves to the cruel trap placed in our path, in the hope that even captive, though well fed, we may be able to retort before being devoured.

The list of traps is long, but I want to describe a specific type that is prostrating itself in front of me at this point in my journey: the trap of publishing in international academic journals. In Brazil, a researcher and/or scientist who wants to pursue a career within universities will necessarily find a scoring logic that allows, or not, their permanence and advancement to more prominent and better paid positions. As in other national systems of science and technology, research funding is linked to a good score, mainly arising from productivity and measured through, for example, number of publications and citations. An important characteristic in the case of Brazil, which differs from countries like the USA, is that funding for scientific research is mostly public, organized through state funding agencies. For this reason, most Brazilian academic journals are free, both for publication and for circulation.

In recent times, the internationalization of research has been a requirement of Brazilian funding agencies. In this scenario, publication in high-impact international journals has become a necessity. In some science and technology systems in other Latin American countries, this requirement is even tougher, with the acceptance of only articles published in journals indexed in repositories such as Web of Science and Scopus, both maintained by private entities seeking profits. The overwhelming majority of journals indexed in such repositories charge a lot of money for publication and access to the article. The amounts that researchers must pay to have their articles published can reach around R$ 20,000. For comparison purposes, the value of the minimum wage in Brazil is R$ 1,320 (about 15x less than the publication cost of the article).

Although most of the time the money to pay for such publications comes from the institutions, not being paid directly by the researchers, the effects produced by this logic of professional permanence are cruel. At the national level, it intensifies competition between researchers and research centers, who need to outperform each other in order to obtain funding. Internationally, such logic keeps the knowledge produced by the poorest countries in the corner, unable to circulate in large centers. This trap works like colonial shackles to which we often have to submit.

But the traps that we will find in our paths are not always so brazen and so painful. In fact, the most dangerous traps are precisely those that we don’t immediately notice and that offer us pleasure. When we are finally able to recognize our status as prey, we are so committed that we try at all costs to convince ourselves that it is better to become captive than to give up the delicious offer they make us. What we are offered is a biochemical comfort well adjusted to the “pharmacopornographic era” of Preciado (2008), which for many of us means a substantial distance from situations of physical suffering and the most varied humiliations, especially intellectual humiliations. In a scenario of growing public attention regarding the degradation of working conditions that researchers are facing, made explicit for example in a vertiginous decline in the mental health of workers who occupy laboratories around the world, this “pleasant” counterpart of working producing technoscientific knowledge that I mention in the last paragraph can only be understood from a class point of view—academic/intellectual work is essentially different from the overwhelming majority of jobs available to workers.

Money, prizes, publications, and recognition are some of the achievements that academic work brings and that activate these biochemical pleasures. Academic work offers comforts that many of us would not have if we had chosen other paths. An example is the possibility of traveling internationally. All the international trips I took were for my academic work. On these trips, we have the possibility of getting in touch with a dimension of cultural capital that was previously inaccessible. When we make our way back to our homeland, we are already transformed. In this movement, it is important to always plant your foot on the ground, exercise your memory, recognize the terrain to know where you are stepping, and always take very small steps. After all, many of the traps are hidden in the ground.

Image of an arapuca, a traditional trap (image by Clarissa Reche)

It took me a long time to understand why Isabelle Stenger’s proposal (2000) of “not hurting established feelings” resonated so much with my colleagues as a strategy to create alliances with scientists and engineers. In my naive rebelliousness, that phrase sounded like a conformist attitude. I wondered if, in exchange for maintaining a “good” relationship, we wouldn’t be giving up the best of what we have as social scientists—our critical capacity. In my master’s degree fieldwork with biohacker scientists, I was surrounded by people who, from within their disciplines, sought to produce science in more open and democratic ways. Maybe that’s why it took me a while to realize that a posture based only on confronting and denouncing the ills of technoscience is fruitless, as it produces an alienating and perverse result: it hides from us, people who research from the human sciences, our responsibility as co-inhabitants of this same space where the scientists we are denouncing.

Complaints are important, yes, and we have lists of them on the tip of our tongues. But Stengers, Haraway, and so many other feminists concerned with technoscience point to the importance of not stopping there. Recognizing our responsibility as co-inhabitants of the scientific knowledge production system is also learning to establish and maintain dialogues, however difficult they may be. And they are. Difficult, tiring, and frustrating. However, the possibility of establishing alliances around common knowledge is also a strategy to keep producing science from joy, as proposed by Stengers (2015) when claiming that the taste for thinking is only possible through encounters capable of increasing our power of understanding, action, and thinking. The trap can also be a bridge to establish such alliances without, at first, hurting established feelings.

The first time that the trap was presented to me as a possible tool for thought-action was when I participated with a group of friends in the speculative anthropology project called FICT, at the University of Osaka. In the group were artists and people from letters, history, and anthropology. The objective was to produce “artifacts” from different timelines, different possibilities created from a fictitious past event: the Black Death had killed many more people, and the European colonial enterprise of the 16th century had failed. Thinking about it was not only challenging, but also quite painful. We were living a pandemic ourselves, with a denialist government, and many people close to us were suffering. But beyond that, the starting point of the project struck us as somewhat violent. By proposing a non-colonial reality, we were forced to think of a world without us, people whose full-life identity comes precisely from the fact that we are daughters and sons of colonial violence.

We refuse to think of a world where we do not exist. The story of how science was established in Brazil is precisely the story of how the dominant classes—politically, economically and culturally—tried to deal with the “problem” of miscegenation. Our first scientists were renowned eugenicists. Their busts still rest in white peace on university campuses, and their names baptize streets and buildings throughout Brazil. Our starting point in the project was a rebellion against the suggested starting point, in an affirmation of our uncomfortable existence. We are the incarnate memory of the violence against the land, against the original peoples of our lands and those who were uprooted from the continent of Africa. We are the incarnate memory of (scientific) racism. But how to exist within a project that predicts our non-existence? How to be there, keep occupying space and communicate to those who hope that we don’t exist that yes, despite everything we are here?

It was Joana Cabral, an anthropologist who works with the Amazonian Wajãpi people, who proposed the trap as a way of occupying the crossroads we were at. Our issue was a communication issue. We needed to communicate the existence of something that shouldn’t exist in the cosmopolitics we were in, but that did exist. Something present but invisible. I believe that this thought was the trigger for Joana to remember the Amerindian traps, especially the trap to “catch” the caipora, an entity from Tupi-Guarani mythology, inhabitant of the forest and owner of all hunt, with whom hunters must negotiate to catch their prey. Such traps were described by Joana as beautiful pieces braided in straw, positioned along the dense forest in the places where caipora usually frequent. The capture system is quite simple: enchanted by the beauty of the piece, the caipora’s attention turns completely to the moths, and their curiosity to learn more about the braid makes them stay there, undoing the braids. Thus, caipora “waste time” in the trap, while people gain time to move through the forest more safely.

At the same time that it holds the caipora’s attention, the trap also communicates its existence to those who walk unaware. We finally managed to make our artifact, a kind of dream diary where we report receiving dream knowledge about how to manage having a party where the most different people can be at. Thus, we seek to face colonialism not as a historical period, but as an entity, a drive from which we will not be able to get rid of—just as we exist, the colonial impetus also exists, persists, and is alive among us. The making of the trap revealed to us that in order to be able to capture, we ourselves need to become aware of our diverse prey conditions.

But the perception of our prey condition cannot be paralyzing. Our malice can certainly enable us to escape from some traps set for us—but not all, never. My proposal is that we cultivate the necessary calm and attention to walk in more or less safe territory, but, at the same time that we perceive ourselves captured and entangled, we are also capable of designing and setting our own traps to make the issues that we formulate capable of going through the academic toughness. Traps capable of opening and sustaining impossible dialogues. What I propose is an insurgent counterattack, or counterspell, to stay with Stengers. It’s a kind of low-intensity direct action, a guerrilla strategy to keep producing scientific knowledge. And so that we can protect our vulnerabilities, remain with joy in the process. It is important to repeat: the trap is not only something to be avoided, but also to be produced. We need to take ownership of capture technologies, collectivize them, and scale them up.

Caceres, Rafael Rodrigues; Sales, Adriana Oliveira de. Memória e feitura de armadilhas Guaraní Ñandeva. II Seminário Internacional Etnologia Guarani: redes de conhecimento e colaborações, 2019.

Beer, Stafford. Designing freedom. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1974.

Gell, Alfred. “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps.” Journal of Material Culture, v. 1, p. 15-38, 1996.

Haraway, D. “Localized Knowledge: The Question of Science for Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14.3 (Autumn 1988): 575-599.

Harding, Sandra. The Science Question in Feminism. New York: Cornell University, 1986.

Preciado, Paul B. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. New York: The Feminist Press, 2008..

Stengers, I. In Catastrophic Times Resisting the Coming Barbarism. London: Open Humanities Press, 2015.

___________. The Invention of Modern Sciences. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Every January, government officials, urban dwellers, and rural families across the state of Ceará, Northeast Brazil anxiously await the rainy season forecasts from Funceme, the Research Institute for Meteorology and Water Resources of Ceará. Yet throughout the state, many also proclaim that Funceme’s forecasts are “wrong,” that the forecasts do not work.

Dona Maria, who lives in a rural community in the municipality of Piquet Carneiro, explained it this way: “The problem with Funceme is this: sometimes it doesn’t work. Here, if I have a… how do you say… a forecast from Funceme, it can work in another municipality. Here it doesn’t work. Funceme predicts rain, for example. But then it rains there. In Juazeiro do Norte, it rains. It doesn’t rain here in Piquet Carneiro. It rains there in Barbalha and Várzea Alegre. And here it doesn’t even drizzle, you know? And that’s why I don’t give it a lot of importance. Do you understand?” (Dona Maria, personal communication, March 7, 2022).[1]

But what does it mean that a forecast is wrong?

Indicating more general rainfall patterns, Funceme’s seasonal forecasts consist of a distribution of probabilities of rainfall below, at, or above the mean for a large geographic region. Because a forecast is a distribution of probabilities, technically, a forecast cannot be “wrong,” though its performance may be evaluated over a period of years. Models may indicate that there is a greater chance of rainfall above average, but lower rainfall levels are still possible. At the same time, forecasts are not made at the household or community-level but rather at the regional level, where a region may be a state or larger geographic area. However, for agricultural families in the sertão, or hinterlands, of Ceará, a forecast is wrong when it rains less (or more) in their community or municipality than what was “promised” by the forecast, and the highest probability becomes deterministic at a very fine scale. That is why for Dona Maria, Funceme’s forecasts work in some areas but not in others.

In this post, I explore the evolution of Funceme and its seasonal forecasting in Ceará, where drought is integral to the collective socioecological memory (Alburque Jr. 1994, 2004; Seigerman et al. 2021). The majority of Ceará forms part of the Brazilian semi-arid region, characterized by distinct rainy and dry seasons, low rainfall levels, and high evaporation rates (de Souza Filho 2018). The droughts of 1877–1879, 1915, 1931, 1973, 1983, 1993, and 1998 evoke memories of unequal suffering in the Cearense sertão, as well as the implementation of large-scale infrastructure solutions in response to drought. The most recent drought (2012 to 2018) is considered the worst drought in Ceará’s history (Marengo, Torres, and Alves 2017).[2] While mortality and migration due to drought have declined dramatically in recent decades, in part due to government conditional cash transfer programs (Nelson and Finan 2009), “crises of collective anxiety about the rainy season” occur frequently and are often provoked by the communication of climatic information (Taddei 2008, 79).[3]

In 1987, Ceará restructured the Secretariat of Water Resources (SRH), and Funceme went from the Foundation of Meteorology and Artificial Rain of Ceará to the Research Institute for Meteorology and Water Resources of Ceará.[4] This name change, fifteen years after Funceme was founded, signified a transition from Funceme as an institution focused on experimental artificial rain production to one whose focus was “water in a general sense” (F. L. Viana, personal communication, August 19, 2022).[5] It has evolved as an innovative institution that advances forecasting modeling, basic environmental studies, and research on sociohydrologic dynamics. These advancements are not linear but rather have been achieved through efforts of Funceme’s most recent presidents, who were tasked to justify Funceme’s role as a research institute after the president from 1995 to 2001 almost dissolved Funceme with his business-like model for the research institute (E. S. P. R. Martins, personal communication, October 25, 2022). Today, government and non-government institutions, from regional to international levels, applaud Funceme. However, Funceme’s innovative character is often overshadowed in rural Ceará by the worry surrounding rainy season predictions.[6]

Since the 1970s, hydrologists have made significant progress in understanding the systems that shape the rainy season in Northeast Brazil, including the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a coupled atmosphere-hydrosphere system in the Atlantic (Hastenrath and Heller 1977, Hastenrath and Greischar 1993).[7] Yet, only in the past couple of decades have researchers at Funceme and around the world developed models to make quantitative forecasts. In its early forecasting years, Funceme employed a climate monitor that used qualitative indicators, including Atlantic and Pacific Ocean conditions, global circulation patterns, and regional studies, to visualize three scenarios without indicating probabilities: rainfall below, at, and above the historic mean (personal communication, F. L. Viana, August 19, 2022). Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, forecasting methods advanced globally, with consensus forecasting as the norm.[8] Funceme has actively contributed to advancements, including the development of seasonal climate forecasts using dynamical downscaling in 1998-1999, the first operational forecast being launched in 2001 (personal communication. E. S. P. R. Martins, October 25, 2022). Dynamic downscaling, also called regionalization, resolves global-scale weather conditions at a finer scale to create more spatially detailed climate information.

Funceme broke conventions by adopting an objective forecast system in 2012 (personal communication. E. S. P. R. Martins, October 25, 2022). It gained independence in forecast production, running the ECHAM4.6 model (an atmospheric general circulation model) and adopting a thirty-year hindcast (1981 to 2010) for its ECHAM4.6 and RSM97 models. Sea surface temperatures were incorporated into the ECHAM4.6, and scenarios were run to better communicate forecast uncertainties. Concurrently, Funceme contributed to a national climate model superset, which helped Funceme establish itself as a national forecasting leader.[9] Today, Funceme uses probabilistic forecasting, which provides the probability that an event (rainfall) of a specific or range of magnitudes may occur in a specific region (the state of Ceará) in a particular time period (a trimester). However, despite forecast improvements, whether these innovations lead to better informed decisions is not clear. Decisions may depend not only on the forecast’s objectivity but also factors including users’ understanding of uncertainty in forecasts, personal or professional interests, and how available information is applied (Morss et al. 2008).

Salience, relevance, authority, and legitimacy are key to the uptake of forecast information by different actors (Taddei 2008). In part, Funceme establishes authority and legitimacy during forecast meetings using graphs that depict forecast model results. Data visualization is a discursive tool for social semiotics (Aiello 2020), as seemingly simple charts substantiate the presented rainfall probabilities. Model complexity, the immense quantity of atmospheric and other environmental data, and fluxes of ambient conditions are flattened into digestible nuggets for non-experts.

At this year’s forecast announcement, Funceme’s president, Dr. Eduardo Sávio P. R. Martins, used a pizza analogy to explain the anxiously awaited rainfall probabilities. As of January 20, the climate forecast indicated probabilities of 10:40:50 (10 percent below average, 40 percent around average, and 50 percent above average). Martins had the audience imagine these probabilities as portions of a pizza: cutting the pizza in half gives 50 percent of the pizza as above-average rainfall. The other half, divided into parts proportional to 40 and 10 percent, represents the other probabilities. Rotating the pizza, you can pick a slice from any of the three options. Rotating it again, you may get a slice from a different part of the pizza, that is, a different rainy season outcome. Martins also emphasized that the models suggested high spatial and temporal variability, addressing common misconceptions held by Dona Maria and others. Rainfall will probably not fall uniformly across Ceará or during the trimester.

Dr. Eduardo Sávio P. R. Martins, the president of Funceme, presents the seasonal forecast for Ceará for the months of February, March, and April on January 20, 2023. The presentation took place at the Governor’s Palace in Fortaleza, Ceará and was live-streamed by Funceme via Instagram.

Directing perceptions about probabilities during public presentations is one strategy Funceme uses to educate its interlocutors, especially the press. To that effect, Martins beseeched those who were to communicate the forecast to ensure they had these concepts correctly explained before publishing, “So that we [Funceme] don’t have a lot of work later on to, let’s say, redo presentations for other groups to clarify communication problems.”[10] While Funceme’s forecasts are shared via social media, including Instagram and WhatsApp, in addition to newspapers and the radio, there is no guarantee that their complete message reaches or changes perceptions of those living in the sertão.

As a publicly facing research institution, Funceme confronts compound challenges of innovating and communicating those innovations in understandable, useful, and usable ways. Throughout the year, Martins discusses the implications of forecasts and climate trends with different government actors. In mid-March, for example, Martins met with the governor of Ceará and the leaders of various government organs to determine flood-risk areas due to strong rains. Funceme’s forecasts also provide technical experts at the state water management company, Cogerh, a baseline to model water availability in the state’s reservoirs to support bulk-water allocation decision-making by river-basin committees, composed of representatives from civil society, industry, and the government (Lemos et al. 2020).

Funceme, a state institution, also faces the challenge of precarity every four years during the gubernatorial elections. Each election poses the possibility of the reconfiguration of the SRH and Funceme. For two decades, Funceme has experienced relative stability, in part a reflection of the technical competence by Martins, now in his seventeenth year as president. The future of Funceme will depend on its ability to adapt to new leadership, potential political influence, and new environment scenarios in the face of rapidly changing climates.

Thank you to Dr. Eduardo Sávio P. R. Martins for his insights, feedback, and collaboration in the development of this research. Also, thank you to Dr. Francisco Vasconcelos Junior and Kim Fernandes for their useful comments on drafts of this post.

[1] Original: “O problema da Funceme é o seguinte às vezes ele não funciona. Aqui, se eu tenho uma, como é que diz uma previsão da Funceme? Ela pode funcionar lá em outro outro município. Aqui não funciona. Ele prevê uma chuva, por exemplo. Mas aí chove. Lá em Juazeiro do Norte não chove aqui em Piquet Carneiro, chove lá em Barbalha e Várzea Alegre. E aqui nem pinga, né? Então é por isso que eu não dou muita importância, entendeu?”

[2] Individually, the rainy seasons of 2012 to 2018 are ranked better than the tenth most critical year in the history of systematic records, but the persistence of drought reveals a very different drought footprint. See for example:

Martins, Eduardo Sávio P. R., Magalhães, Antônio. R., and Diógenes Fontenele. 2017. “A seca plurianual de 2010-2017 no Nordeste e seus impactos.” Parcerias Estratégicas 22: 17-40.

Martins, Eduardo Sávio P. R. and Francisco de Chagas Vasconcelos Júnior. “O clima da Região Nordeste entre 2009 e 2017: Monitoramento e Previsão.” 2017. Parcerias Estratégicas 22: 63-80.

Escada, Paulo, Caio A. S. Coelho, Renzo Taddei, Suraje Dessai, Iracema F. A. Cavalcanti, Roberto Donato, Mary T. Kayano, et al. 2021. “Climate services in Brazil: Past, present, and future perspectives.” Climate Services 24: 100276.

[3] Original: “crises de ansiedade coletiva em relação à estação de chuvas”; See also: Taddei, Renzo. 2005. Of clouds and streams, prophets and profits: The political semiotics of climate and water in the Brazilian Northeast. Doctoral thesis. Columbia University.

[4] Fundação Cearense de Meteorologia e Chuvas Artificiais and the Fundação Cearense de Meteorologia e Recursos Hídricos, respectively.

[5] Original: “água no sentido geral”

[6] People in the sertão are also inundated with sometimes conflicting rainfall information from a variety of sources—from national agencies to private institutions. This poses a challenge for Funceme to maintain its legitimacy among rural community members, who link conflicting rainfall information from various sources with Funceme because the information is all about rain.

[7] Meteorological drought has been related to anomalies in the Atlantic system, which result in the ITCZ remaining anomalously far north (Hastenrath and Greischar 1993). Meteorological drought is defined as rainfall in the category below the mean. We can imagine having thirty years for which we put rainfall in order from lowest to highest and divide then in the ten years into three categories: The first ten years (below average), the last ten years (above average), and the ten years between these two category, which represent rainfall around the average. The El Niño-South Oscillation (ENSO) and the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) also influence climate patterns at varying temporal scales. See for example:

Kayano, Mary Toshie, and Vinicius Buscioli Capistrano. “How the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (Amo) Modifies the Enso Influence on the South American Rainfall.” International Journal of Climatology 34(1): 162-78.

Vasconcelos Junior, Francisco das Chagas, Charles Jones, and Adilson Wagner Gandu. 2018. “Interannual and Intraseasonal Variations of the Onset and Demise of the Pre-Wet Season and the Wet Season in the Northern Northeast Brazil.” Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia 33: 472-484.

[8] A significant level of subjectivity is added when a group of forecasters determine a single forecast through consensus. In this negotiation process, social and political pressures (e.g., the need to establish a forecast that appeases farmers or state agencies) may drive outcomes. Conversely, objective forecasts are produced directly from the selected models, without a negotiation process.

[9] The superset included a statistical model for Brazil (INMET) and four global atmospheric models (one from Funceme and three from the National Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies). Other projects with sociotechnological significance, including the development of a national drought monitor, attest to the innovative and socially driven character of Funceme.

[10] Original: “[P]ara a gente depois não ter um trabalho muito grande de, digamos assim, de refazer apresentações em outros grupos para esclarecer problemas de comunicação.”

Aiello, Giorgia. 2020. “Inventorizing, situating, transforming: Social semiotics and data visualization.” In Data Visualization in Society, edited by Martin Engebretsen and Helen Kennedy, 49-62. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Albuquerque Jr, Durval Muniz de. 1994. “Palavras que calcinam, palavras que dominam: a invenção da seca do Nordeste.” Revista Brasileira de História 14 (28): 111-120. [pdf]

—. 2004. The invention of the Brazilian Northeast. Durham: Duke University Press.

de Souza Filho, Francisco. 2018. Projecto Ceará 2050. Fortaleza (Brazil).

Hastenrath, Stefan, and Leon Heller. 1977. “Dynamics of climatic hazards in northeast Brazil.” Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 103 (435): 77-92.

Hastenrath, Stefan, and Lawrence Greischar. 1993. “Further Work on the Prediction of Northeast Brazil Rainfall Anomalies.” Journal of Climate 6 (4): 743-758.

Lemos, Maria Carmen, Bruno Peregrina Puga, Rosa Maria Formiga-Johnsson, and Cydney Kate Seigerman. 2020. “Building on adaptive capacity to extreme events in Brazil: water reform, participation, and climate information across four river basins.” Regional Environmental Change 20 (2): 53.

Marengo, Jose A., Roger Rodrigues Torres, and Lincoln Muniz Alves. 2017. “Drought in Northeast Brazil—past, present, and future.” Theoretical and Applied Climatology 129 (3): 1189-1200.

Morss, Rebecca E., Julie L. Demuth, and Jeffrey K. Lazo. 2008. “Communicating Uncertainty in Weather Forecasts: A Survey of the U.S. Public.” Weather and Forecasting 23 (5): 974-991

Nelson Donald, R., and J. Finan Timothy. 2009. “Praying for Drought: Persistent Vulnerability and the Politics of Patronage in Ceará, Northeast Brazil.” American Anthropologist 111 (3): 302-316.

Seigerman, Cydney K., Raul. L. P. Basílio, and Donald R. Nelson. 2021. “Secas entrelaçadas: uma abordagem integrativa para explorar a sobreposição parcial e as divisões volúveis entre definições, experiências e memórias da seca no Ceará, Brasil.” In Tempo e memória ambiental : etnografia da duração das paisagens citadinas, edited by Ana Luiza Carvalho da Rocha and Cornelia Eckert, 25-54. Brasília: ABA Publicações.

Taddei, Renzo. 2008. “A comunicação social de informações sobre tempo e clima: o ponto de vista do usuário.” Boletim SBMET: 76-86. [pdf]

It’s estimated that about a third of all food produced worldwide every year, which is approximately 1.3 billion tons, is estimated to be wasted. Aravita, a Brazilian artificial intelligence startup, thinks that supermarkets are the best place to start fixing this problem.

Marco Perlman, co-founder and CEO, started the company with Aline Azevedo and Bruno Schrappe in 2022 to tackle waste in the fourth-largest food producing country in the world where 33 million Brazilians have some type of food insecurity.

Aravita is developing an AI-powered solution for supermarkets that looks at variables, including climate, seasonality, consumer behavior and economic scenario, to manage the purchasing of fresh food — mainly fruits and vegetables — to reduce the instances of surplus items and lost sales due to waste. At the same time, the software increases the availability of items in demand.

“Supermarkets are our target audience because they are a great place to drive the first wedge of data availability,” Perlman told TechCrunch. “They have point-of-sale consumer data, and this is the data that we need to start making the predictions for low-demand forecasting. Unlike other parts of the supply chain, where the data is much harder to get a hold of, eventually we think that this will be digitized.”

Aravita is still in the very early stages: It has a conceptual prototype and started a pilot with a mid-sized supermarket chain near São Paulo and has the first set of algorithms developed. It is also in the process of integrating the first database of historical data into that model.

However, that first pilot didn’t come easy. Perlman recalls that potential customers were initially worried that startups were “having difficulty raising money, hiring and surviving,” and were uncomfortable giving store data to a company without financial resources that could stick around.

Aravita co-founders, Marco Perlman, Aline Azevedo and Bruno Schrappe. Image Credits: Aravita

So the trio started reaching out to investors and was able to secure a $2.5 million investment earlier this year, co-led by Qualcomm Ventures and 17Sigma.

“Fresh food management is highly fragmented and complex,” said Michel Glezer, director of Qualcomm Wireless GmbH and director at Qualcomm Ventures, in a written statement. “Aravita’s solution enables retailers to optimize inventory management, helping increase efficiencies and reduce waste.”

Joining those two firms were Bridge, DGF Investimentos, Alexia Ventures, BigBets, Norte Capital and a group of angel investors, including ClearSale partner and CEO Bernardo Lustosa and Flávio Jansen, former CEO of LocaWeb and Submarino.

Aravita is now in good company among other startups tackling food waste that also recently attracted venture capital, including Divert, which is trying to stop food before it reaches landfills; Diferente, also in Brazil, that is finding places for imperfect produce; and food resale app Recelery. They join other companies like Shelf Engine, Apeel, OLIO, Imperfect Foods, Mori and Phood Solutions.

The next steps are to develop the solution over the next few months and add a second pilot customer, Perlman said. He expects to have product-market fit next year and the ability to “step on the gas to accelerate” Aravita’s business model into other supermarket departments, including baked goods, pastry, cold cuts, fish and meat.

The new capital enables the company to hire additional employees and for future innovation, including inventory management, point-of-sale integration and technology development like AI and computer vision for process automation.

Qualcomm-backed Aravita wants to help Brazilian supermarkets control food waste by Christine Hall originally published on TechCrunch

Guest post by Ladyane Souza, Luise Koch, Maria Paula Russo Riva, and Natália Leal

Women who break the glass ceiling in politics are often depicted as disrupting the long-standing patriarchal structures that have traditionally kept women away from the public eye. The stereotypical “ideal” politician is usually based on a male perspective of strength and having a “thick skin,” which reinforces these patriarchal norms. Efforts to maintain the gendered status quo in politics are widespread, and include delegitimization and intimidation tactics such as misogynistic attacks or rape threats. Technological innovations provide additional fertile ground for such intimidation—and even violence—against women in politics. Though much of online hate is shared through social media, the consequences spill over into the offline world. Online abuse imposes financial and time-consuming burdens on female politicians who must, in addition to other pressing tasks, improve security, combat disinformation, and report perpetrators.

Many women politicians believe that they simply have to endure violence in order not to be perceived as emotional, weak, or unfit for the job. Some have managed to thrive politically despite being confronted with severe digital violence, like the 2021 German Green party candidate for chancellor, Annalena Baerbock, who is now minister for foreign affairs. Other female politicians decide to exit politics, like two former leftist congresswomen from Brazil who publicly announced their decision to not run in the 2022 elections after being targeted by severe online hate.

Why do some female candidates and victims of online violence drop out of politics while others endure? Our research shows that there are no simple answers. As part of a research project on online misogyny against politically active women, we interviewed five female Brazilian candidates for parliament. We found that women react differently to online violence: some simply ignore it or shrug it off, some choose to respond, and others stop engaging online altogether.

Since the use of social media is greatest among 25–34 year-olds, it is likely that younger female politicians who rely on social media are especially susceptible to being targeted. Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups also tend to receive disproportionately higher amounts of abuse than many white female politicians. Personal characteristics such as age, skin color, and ethnicity are thus factors likely to increase the risk of women being targets of abuse and leaving politics. Furthermore, the severity of abuse, recurrence of attacks, and countries’ legal support mechanisms may play a crucial role in women’s decisions to persist in or exit politics.

The ultimate goal of violence against women in politics is to convey that women are not welcome at the political table. This means that when female politicians leave public life due to online violence, it is not because they choose to do so, but rather because patriarchally led structural forces succeeded in achieving their intended end, which is to cast off all women to political ostracism one by one. Because the problem is structural, the solutions need to be structural too. The blame for quitting must not be put on the female politicians individually, but rather on the absence of mechanisms to protect these women in the first place. Yet, the topic continues to be covered as a matter of personal choice and weakness, which disregards that online violence seeks to achieve political outcomes.

What must be done then to protect women in office from online violence? Apart from obvious proposals involving social media platforms preemptively countering and removing hateful content, multi-sectoral responses should be considered. This could involve putting in place initiatives such as developing support networks; creating comprehensive legal frameworks protecting digital rights; improving data collection on prevalence, incidences, and experiences of online harassment; and training public servants, communicators, and psychologists to address violence against women in politics and its victims.

Australia’s online safety regulator eSafety is a good model. The world’s first government agency dedicated to keeping people safer online, eSafety has formed a global partnership involving international organizations, civil society, and the private sector to strengthen laws to deter perpetrators of abuse and hold them accountable. The German non-profit HateAid is another—the group provides counseling and legal support in cases of digital violence.

One further blind spot that must be urgently tackled is the lack of funding to address the digital and physical security of female candidates. An understanding is beginning to emerge on the harms from gender-based attacks online, with Sweden leading the way with its first “online rape” conviction.

Women’s participation in politics is crucial, and much progress has been made in opening up the political space. But more needs to be done to protect women from the special burden they face of online abuse.

Ladyane Souza is a lawyer, consultant, and researcher who holds a Master’s in Human Rights from the University of Brasilia. Luise Koch is an economist and researcher who is pursuing her PhD at the Technical University of Munich. Maria Paula Russo Riva is a human rights lawyer and political scientist. Natália Leal is a journalist and CEO at Agência Lupa, the first fact-checking institution in Brazil and the 2021 Knight International Journalism Award winner.

Guest post by Shauna N. Gillooly and Philip Luke Johnson

In 2020, a university campus in Bogotá, Colombia was festooned with flyers threatening “the children of professors that indoctrinate their students into communism.” A year earlier, a campus in Medellín was plastered with pamphlets, this time threatening students that engaged in political activity instead of quietly getting on with their studies. Both messages were signed by the Águilas Negras, a notorious criminal band. While the strength of this group has been disputed, for those targeted by the threats—and many besides—these messages could hardly be dismissed as anything less than terrifying.

These messages are hardly an isolated occurrence. Hundreds of threatening messages signed by the Águilas Negras have appeared across Colombia in recent years. Gangs in Brazil have published threatening messages in newspapers, while in Mexico, criminal actors sometimes use “narco-messages” to threaten rivals, officials, or other members of the public. Although the practice is relatively widespread, it raises questions about the behavior and power of criminal actors.

Most scholarship shows that criminal actors maintain a low profile, wielding power through clandestine means of coercion, corruption, and cooptation. Keeping a low profile reduces the costs of run-ins with rivals or the law. Criminal actors certainly do make use of public, sometimes spectacular violence, but primarily when the government is incapable or inefficient at punishing (or protecting) organized crime. Even so, most criminal actors moderate the frequency and visibility of their violence most of the time.

Threats are a particularly useful way to exert subtle power, as they leave no mark, no “smoking gun.” For a group with an established reputation, the mere whisper of a threat may be enough to induce compliance on the part of their targets (indeed, some actors with established reputations expend considerable resources to prevent pretenders from issuing threats in their name). Publicizing threats thus seems to undermine one of the main advantages of threats; the ability to coerce while reducing the risks associated with the actual use of violence. Why, then, would criminal actors publicize their threats to far wider audiences than the intended targets?

Our new research takes up this question by analyzing the content of threatening messages from four different criminal groups in Colombia and Mexico. These range from neo-paramilitary groups in Colombia, such as the Gaitanistas, to the pseudo-evangelical cartel, the Caballeros Templarios, in Mexico. Breaking the messages down into a “grammar” of their core elements—such as who is the target of the violence, what conditions are placed on the violence, and on whose behalf violence is threatened—we identify consistencies and variations in the use of public threats across these varied cases.

We find that when criminal actors publicize threats, they are projecting order; delineating their rules on the ground, dictating who (or what) is welcome and who will find no place on their turf. The threats may also induce compliance from the target, but the publicity serves this important additional function. The orders projected by different groups share some common elements: they position the criminal actors as mediators between the in-group of decent society and the out-group of deviants from that society (the threateners are also defining—sometimes with extreme prejudice—who they consider deviant). In positioning themselves as violent mediators, criminal actors displace other possible mediators, such as rival groups as well as non-violent civil society actors.

At the same time, the specific order projected varies across groups. Some groups threaten future violence that is conditional, while others threaten violence as the inevitable continuation of actions already occurring. Similarly, the specific in-group and out-group projected by threats varies. The Gaitanistas and Águilas Negras in Colombia both use the language of social cleansing, but the Águilas target an expansive out-group of leftists and alleged guerrilla sympathizers while barely mentioning an in-group, while the Gaitanistas invoke a national in-group but target only localized rivals.

Public threats can be quite low-tech, like the flyers that blanketed campuses in Colombia, but regardless of the medium, they aim to maximize publicity. This highlights the vital role of the media in impeding or permitting the projection of criminal orders. Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, with criminal actors threatening and sometimes killing media workers to shape the flow of information (officials are also deeply implicated in this). Preserving the safety and autonomy of the press—even where reporting uncovers uncomfortable truths for those in power—is thus absolutely vital to limiting the influence of public threats and criminal orders. In interviews, however, journalists told us that the government protection mechanism is unreliable and often conditioned on favorable reporting.

Criminal governance is often treated as damaging the “fabric of society.” While we often think of this damage in terms of the direct use of violence, we need to examine not only how criminal actors kill, but also how they talk, persuade, and project. We also need to think about violence beyond the act itself; the hint or threat of violence can have powerful effects on direct targets and wider society. From a safe distance, we might question the low-tech or seemingly unsophisticated threats—pundits in Mexico initially mocked the poor spelling of narco-messages—but this does not mean that they are ineffective tools. Nor does it means that the people closer to the threats can afford to discount them.

Shauna N. Gillooly (@ShaunaGillooly) is a postdoctoral fellow at the Global Research Institute housed at William and Mary, and an affiliated researcher with Instituto PENSAR at Pontifica Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, Colombia. Philip Luke Johnson (@phillegitimate) is a lecturer at Princeton University.

Enlarge / Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva kisses a child onstage at the end of a speech to supporters. (credit: Horacio Villalobos / Contributor | Corbis News)

“Unearth all the rats that have seized power and shoot them,” read an ad approved by Facebook just days after a mob violently stormed government buildings in Brazil’s capital.

That violence was fueled by false election interference claims, mirroring attacks in the United States on January 6, 2021. Previously, Facebook-owner Meta said it was dedicated to blocking content designed to incite more post-election violence in Brazil. Yet today, the human rights organization Global Witness published results of a test that shows Meta is seemingly still accepting ads that do exactly that.

Global Witness submitted 16 ads to Facebook, with some calling on people to storm government buildings, others describing the election as stolen, and some even calling for the deaths of children whose parents voted for Brazil’s new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Facebook approved all but two ads, which Global Witness digital threats campaigner Rosie Sharpe said proved that Facebook is not doing enough to enforce its ad policies restricting such violent content.