A few days ago, when I was about halfway through the book, I wondered aloud on Twitter whether Anna M. Grzymała-Busse’s Sacred Foundations: The Religious and Medieval Roots of the European State might need to join the mini-canon of Schmitt-style genealogical political theology. Having finished it, I now think it provides a key point of reference for a lot of projects in that strange field, though it is very much not in the “style” of the most influential works (of the kinds of works that I have advocated adding to the mini-canon, like Caliban and the Witch).

It is a sober empirical analysis, at times even a little boring, but it supplies something crucial: an actual concrete mechanism for the kind of “secularization of theological concepts” that are our stock in trade. In a way, Grzymała-Busse’s lack of conceptual or theological ambition is necessary for her to uncover what has been hiding in plain sight: state institutions in medieval Europe quite literally copied practices and procedures from papal models. The reasons for this are both grandiose and mundane — on the one hand, the papacy obvious carried with it a unique kind of spiritual authority, but on the other hand, the church was the only institution that looked like it knew what it was doing. For things like literacy, documentation, regular procedures, disputes based on precedent and evidence, etc., etc., the church was for many centuries the only game in town.

The motivation to adopt church models for governance grew out of the papacy’s temporal ambitions, which produced a rivalry with secular states. In Grzymała-Busse’s telling, it also arguably led to a secularization of the church itself, as the papacy’s growing administrative efficiency and ability to project power went hand in hand with growing corruption and declining interest in spiritual and theological matters in favor of law. States that were lucky were able to adopt church templates and create their own parallel structures, allowing them to administer justice, collect taxes, and do all the other things at which the church excelled. States that were unlucky — such as the Holy Roman Empire or the divided Italian peninsula — found themselves intentionally impeding from developing the kinds of centralized power structures that would allow such ecclesiastical borrowings.

Grzymała-Busse’s main goal is to argue against purely secular accounts of state formation, the most popular of which attribute state centralization either to the demands of warfare, the need to develop some form of consensus to collect taxes, or both combined. As she shows — fairly conclusively in my view — those theories simply cannot be right. And in her concluding pages, she suggests that the idiosyncratic process of state formation in Europe, which was the only part of the world that had a powerful autonomous trans-national religious institution at the crucial period, should lead political theorists to make less sweeping claims about the universality or necessity of European state structures, much less the processes that led to them.

To me, the most interesting part of her argument from the perspective of “my” preferred brand of political theology is the view that the notion of territorial sovereignty actually grows out of the papacy’s contingent political strategies during the high middle ages. Grzymała-Busse argues that the notion that all kings are peers and no secular ruler has power over a king in his own territory was actually meant to head off the rise of a powerful emperor figure to displace the pope — but the more the pope grew to function as precisely that type of figure, the more the notion of territorial sovereignty became a weapon against papal interference as well. In short, the Westphalian/United Nations model — in which the world is parcelled out among sovereign territorial units that are all to be treated as peers, with interference in their internal affairs being prohibited except in extreme cases based on international agreement — that has hamstrung any attempt at global regulation of capital or any binding climate action, effectively dooming humanity to live on a permanently less hospitable climate… turns out to stem from an over-clever political strategy on the part of some 13th-century pope. It sounds almost absurd when you put it that way.

Grzymała-Busse’s book abounds in such ironies. Every innovation that the papacy introduced to shore up its power in the short run wound up empowering temporal rulers in the long run. The very religious authority that provided the popes the opportunity to fill Europe’s power vaccuum — and in the case of Germany and Italy, fatally exacerbate it with such skill and precision that it would persist for centuries after the conflict between church and state was decisively won by the latter — prevented the papacy from assuming the imperial prerogatives it worked so hard to prevent anyone else from having. Perhaps we can see now why Carl Schmitt was so enamored with the ius publicum Europaeum — it is quite literally a secularization of the papacy’s attempt at the indirect governance of Europe. (Meanwhile, I am at a loss for what this book could offer to the “politically-engaged theology” construal of political theology, because so much of what was formative for the “positive” aspects of secular modernity came from the “bad” period of papal history.)

There is more to say about this book, though perhaps my suggestion on Twitter that this book could serve as fodder for a book event was premature. It is a little too specialized and conceptually dry to spur the kind of discussion we normally aim to have. But I hope my political theology colleagues will read it, and if any of them have thoughts about it that go beyond what I say in this post, I would be happy to host them here.

0691245088.01._SCLZZZZZZZ_SX500_

akotsko

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) is one of the two most famous Catholic theologians and philosophers; the other is Augustine (354–430). Seven hundred years ago, on 18 July 1323, Pope John XXII presided at Aquinas’s canonization as a saint. In 1567, Pope Pius V proclaimed Aquinas to be a “Doctor of the Church,” one whose teachings occupy a special place in Catholic theology. Thomas was the first thinker after the time of the Church Fathers to be so honored. In 1879 Pope Leo XIII issued a famous encyclical, Aeterni Patris: On the Restoration of Christian Philosophy, calling on all Catholic educational institutions to give pride of place to the theology and philosophy of Thomas Aquinas. Although today he is a well-established authority in both philosophy and theology, in his own time he was considered a revolutionary thinker whose views challenged the accepted intellectual establishment of the West.

As a young man in Italy, Thomas joined the recently founded Dominican Order. Along with the Franciscans, the Dominicans were part of a widespread reform movement within the Catholic Church. In many ways these new religious orders were urban-based youth movements and, to be effective in their apostolate of reform in the Church, the Dominicans sought out the ablest young men and quickly established houses of study in the great university centers, such as Bologna, Paris, and Oxford.

Thomas traveled north to Paris (1245) to study with Albert the Great at the University of Paris. Albert was already well known for his work in philosophy, theology, and the natural sciences. Like other Dominicans of his time, Thomas walked to Paris from Italy; and then, with Albert, he walked to Cologne (1248) where the Dominicans were establishing another center of studies. He came back to Paris (in 1252) to complete his studies to become a Master of Theology. After three years in Paris, he spent the next ten years in various places in Italy, only to return to Paris in the late 1260s. There, he once again occupied a chair as Master of Theology and confronted various intellectual and institutional challenges, especially concerning the proper relationship between philosophy and theology.

In his own time, Aquinas was considered a revolutionary thinker whose views challenged the accepted intellectual establishment of the West.

Aristotelian Revolution

Universities in the thirteenth century were relatively new institutions—centers of lively intellectual life. In addition to a liberal arts faculty, the universities had advanced faculties of law, medicine, and theology. Paris was especially famous for its faculty of theology. Thomas was a member of a brand-new religious order, and his professional life was often connected with this new institution in the West, the university. The growing intellectual authority, and relative institutional autonomy, of the new universities often represented a challenge to the established order, both religious and secular.

Thomas lived at a critical juncture in the history of Western culture. The vast intellectual revolution in which he participated was the result of the translation into Latin of almost all the works of Aristotle. Aristotle offered, so it seemed, a comprehensive understanding of man, of the world, and even of God. In the Divine Comedy, Dante’s Virgil calls Aristotle “the master of those who know.”

Aristotle’s works came to the Latin West in the late twelfth century and first half of the thirteenth century, with a set of very compelling, and often conflicting, interpretations from Muslim and Jewish sources: thinkers such as Avicenna, Averroës, and Maimonides. How should Christian theologians react to this new way of understanding things? Aristotle’s claims about the eternity of the world, the mortality of the human soul, and how to understand happiness seemed to represent a fundamental challenge to Christian revelation. Should the teaching of Aristotle be rejected, or at least restricted? Many Christian thinkers in the thirteenth century thought so, and there were various attempts—mostly unsuccessful—throughout the century to ban Aristotle from the curriculum of the new universities. The most famous were lists of condemned propositions in 1270 and 1277, issued by the Bishop of Paris, Étienne Tempier.

Thomas, following his teacher Albert, was among the first to see, and to see profoundly, the value for Christian theology that Aristotle’s scientific and philosophical revolution offered. Thomas was first of all a theologian, committed to setting forth clearly the fundamentals of the Christian faith. But, precisely because he was a theologian, he recognized that he had to be a philosopher and have scientific knowledge as well. His most famous theological work, the Summa Theologiae, contains many philosophical arguments that have their own formal independence and validity, yet are organized in the service of Christian truth. Thomas recognized that whatever truths science and philosophy disclose cannot, in the final analysis, be a threat to truths divinely revealed by God: after all, God is the author of all truth—the truths of both reason and faith. Thomas thought that by reason alone it was possible to demonstrate not only that there is a God but that this God is the creator of all that is. He argued that faith perfects and completes what reason can tell us about the Creator and all creatures.

Precisely because he was a theologian, Aquinas recognized that he had to be a philosopher and have scientific knowledge as well.

As an astute student of Aristotle, Thomas was critical not only of those who ignored Aristotle, but also of those who, sometimes in the tradition of Averroës, read Aristotle in a way that did indeed result in contradictions of Christian belief. Thomas’s philosophical position was not mainstream in his own day; rather, his more traditional colleagues’ views were more widely accepted. Nowhere was this difference more apparent than in debates about the proper relationship between philosophy and theology on a wide variety of questions about human nature and the doctrine of creation. Those opposed to Thomas came from what can broadly be called an Augustinian tradition, which resolutely insisted that philosophy must always teach what faith affirms. Thomas did reject the kind of excessive philosophical autonomy found in Averroës, but he also rejected the tendency toward fideism found in his more traditionalist opponents.

Thomas wrote extensive commentaries on major Aristotelian treatises, such as the Physics, the De Anima (On the Soul), the Posterior Analytics, the Metaphysics, and the Nicomachean Ethics, in which he sought to present comprehensive views of these subjects. One can see Thomas employing principles drawn from Aristotle, as well as from other sources in Greek philosophy, in his wide-ranging collections of disputed questions On Truth and On the Power of God, in Summa contra Gentiles, and even in his biblical commentaries.

Creation and Causality

Throughout his writings, Thomas is keen to emphasize the importance of thinking analogically: recognizing, for example, that to speak of God as cause and of creatures as causes requires that the term “cause” be predicated of both God and creatures in a way that is both similar and different. For Thomas, an omnipotent God, complete cause of all that is, does not challenge the existence of real causes in nature, causes that, for example, the natural sciences disclose. God’s power is so great that He causes all created causes to be the causes that they are.

One of his greatest insights concerns a proper understanding of God’s act of creating and its relationship to science. The natural sciences explain changes in the world; creation, on the other hand, is a metaphysical and theological account of the very existence of things, not of changes in things. Such a distinction remains useful for discussions in our own day about the philosophical and theological implications of evolutionary biology and cosmology. The subject of these disciplines is change, indeed change on a grand scale. But as Thomas would remind us, creation is not a change, since any change requires something that changes. Rather, creation is a metaphysical relationship of dependence. Creation out of nothing does not mean that God changes “nothing” into something. Any creature separated from God’s causality would be nothing at all. Creation is not primarily some distant event; it is the ongoing causing of the existence of whatever is.

In one of the more radical sentences written in the thirteenth century, Thomas claimed that “not only does faith hold that there is creation, but reason also demonstrates creation.” Here he is distinguishing between a philosophical and a theological analysis of creation. Arguments in reason for the world’s being created occur in the discipline of metaphysics: from the distinction between what it means for something to be (its essence) and its existence. This distinction ultimately leads to the affirmation that all existence necessarily has a cause.

The philosophical sense of creation concerns the fundamental dependence of any creature’s being on the constant causality of the Creator. For Thomas, an eternal universe would be just as much a created universe as a universe with a temporal beginning. From the time of the Church Fathers, theologians always contrasted an eternal universe with a created one. Thomas did believe that the universe had a temporal beginning, but he thought that such knowledge was exclusively a matter of divine revelation, as disclosed in the opening of Genesis and dogmatically affirmed by the Fourth Lateran Council (1215).

The theological sense of creation incorporates the philosophical sense. Thomas viewed creation as much more than what reason alone discovers. With faith, he sees all of reality coming from God as a manifestation of God’s goodness and ordered to God as its end. This relationship is a grand panorama of out-flow and return, analogous to the dynamic life of the Persons of the Trinity.

With faith, Aquinas sees all of reality coming from God as a manifestation of God’s goodness and ordered to God as its end.

As the German philosopher and historian Joseph Pieper observed, the doctrine of creation is the key to almost all of Thomas’s thought. The revolutionary nature of Thomas’s position on creation is evident in the way it differs from that of his teacher, Albert the Great, and his colleague at the University of Paris, Bonaventure. Both thought that the fact of creation could only be known by faith and that a created world necessarily meant a world with a temporal beginning. Neither fully appreciated Thomas’s observation that creation is not a change. In fact, one of the condemnations of 1277 by the Bishop of Paris noted that it was an error to hold that creation is not a change.

It may be difficult for us to appreciate the radical nature of Thomas’s thought, especially his brilliant synthesis of faith and reason that honored the appropriate autonomy of each. Thomas does not fit easily into a philosophical or a theological category. He thought that human beings could come to knowledge of the world and of God, but he also recognized that a creature’s knowledge of the Creator must always fall short of what and who the Creator is.

For Thomas, reason—deployed in all the intellectual disciplines (including philosophy and the natural sciences)—is a necessary complement to religious faith. After all, a believer is a human being: a rational animal. Faith perfects but does not abolish what reason discloses. In deploying his understanding of the relationship between reason and faith, Thomas offered what were for his time radically novel views about nature, human nature, and God. What commends these views to us—and what was later realized by the Catholic Church—is not their novelty but their truth. Ironically, in the context of today’s intellectual currents that reject metaphysics and embrace various forms of materialism, Thomas’s thought is once again a radical, if not revolutionary, enterprise.

Guest post by Sabine Carey, Marcela Ibáñez, and Eline Drury Løvlien

On April 10, 1998, various political parties in Northern Ireland, Great Britain, and the Republic of Ireland signed a peace deal ending decades of violent conflict. Twenty-five years later, the Good Friday Agreement remains an example of complex but successful peace negotiations that ended the conflict era known as The Troubles.

Since the agreement, Northern Ireland has experienced a sharp decline in violence. But sectarian divisions continue as a constant feature in everyday life. Peace walls remain in many cities, separating predominantly Catholic nationalists from predominantly Protestant unionist and loyalist neighborhoods. Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol increased tensions between the previously warring communities, leading to an upsurge in sectarian violence, which has been a great cause of concern.

In March 2022, we conducted an online survey to understand attitudes toward sectarianism among Northern Ireland’s adult population. Our results show that sectarianism continues to impact perceptions and attitudes in Northern Ireland. The continued presence of paramilitaries is still a divisive issue that follows not just sectarian lines but also has a strong gender component.

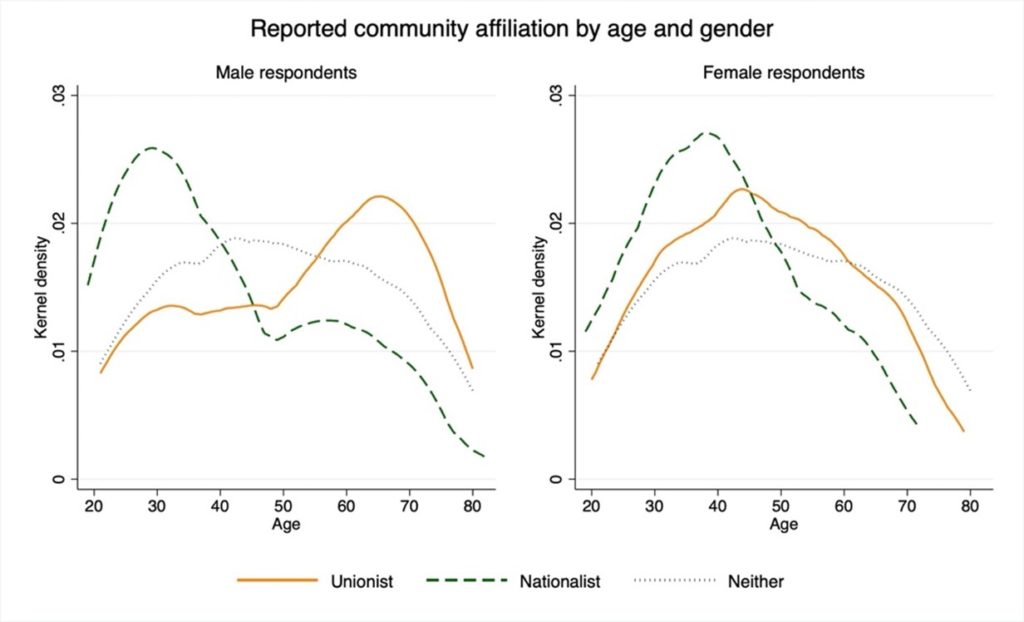

Our findings show that the pattern of who identifies as Unionist or Nationalist closely resembles the patterns of who reports having a Protestant or Catholic background. Unionists prefer a closer political union with Great Britain and are predominantly Protestant, Nationalists are overwhelmingly Catholic and are in favor of joining the Republic of Ireland.

Catholic and Nationalist identities appear to have a greater salience for the post-agreement generations than for older generations who lived through the Troubles. For Protestant and Unionist respondents, the opposite is the case, as religious background and community affiliation have a higher salience among older groups, particularly among men. Among the adults we surveyed, for men the modal age of those identifying as Unionists is 58 years, for women it is 46.

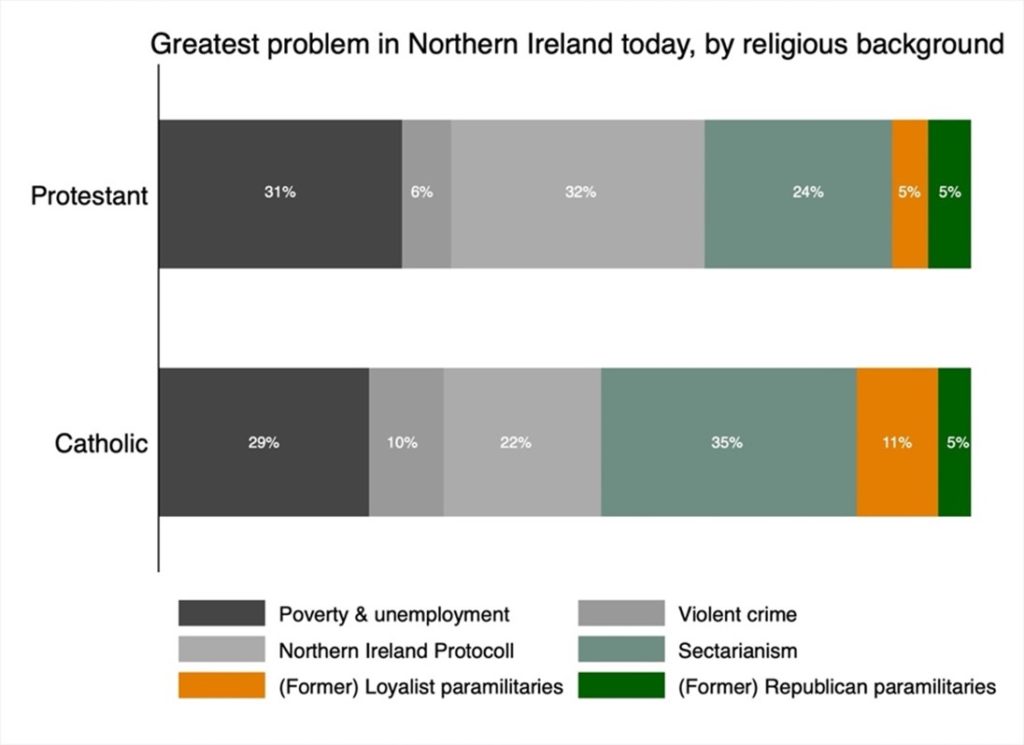

When asked about the greatest problem facing Northern Ireland today, sectarianism still features strongly among both communities. Today, the fault lines of the conflict seem to resonate more with those from a Catholic background than with those from a Protestant background. While Protestants were predominantly concerned with poverty and crime, among Catholics sectarianism emerged most often as the greatest concern. Just over 50 percent of Catholic respondents mentioned an aspect relating to the Troubles (sectarianism or paramilitaries) as the greatest problem today, compared to only 39 percent of Protestant respondents. Most Protestant respondents selected Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol as the greatest problem, reflecting concerns of the Protestant community discussed in a Political Violence At A Glance post from 2021.

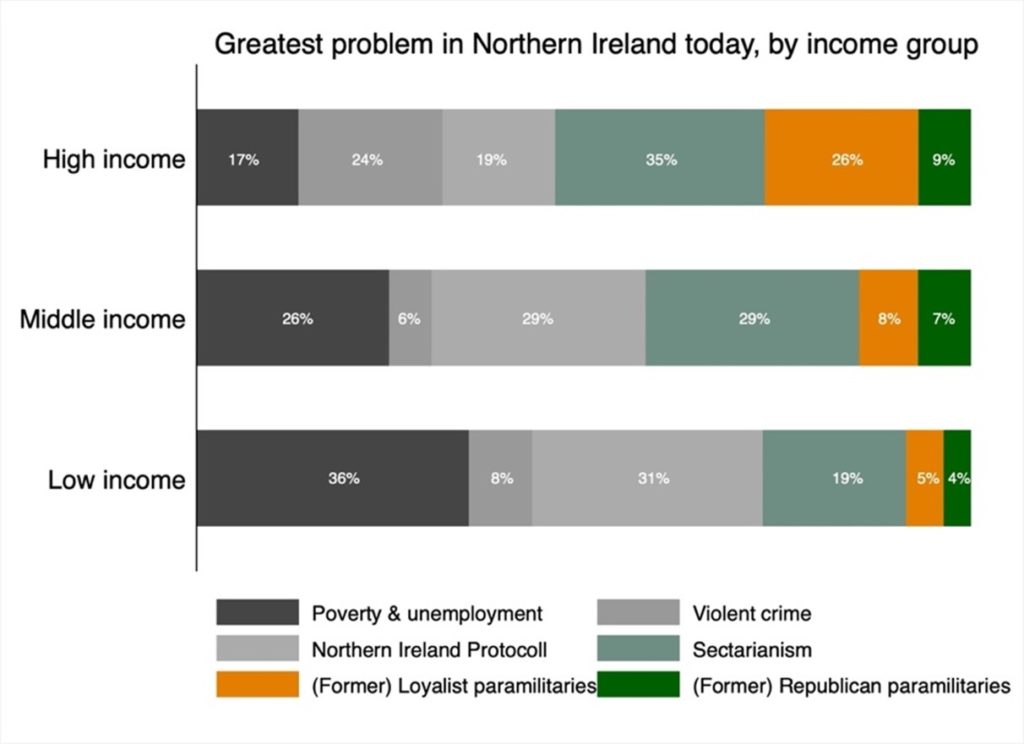

To what extent does economic status drive concerns? Those who see themselves as belonging to a lower-income group were more likely to identify poverty and unemployment as the greatest problem. Concerns about sectarianism and (former) paramilitary groups appeared most prevalent among those who placed themselves in the high-income group.

The continued presence of Loyalist and Republican paramilitaries is a noticeable feature in post-conflict Northern Ireland. While they are predominantly associated with violence and crime, some view them as a source of security and stability. While our findings show that concerns about paramilitaries were more prevalent among high-income earners, the perception of paramilitaries has a significant gender component. Nearly 50 percent of male Catholic respondents attributed a controlling influence to paramilitaries in their area. And while most of them saw these groups as a source of fear and intimidation, 32 percent agreed that the paramilitaries kept their local area safe. But only 5 percent of female Catholic respondents felt similarly. This difference is not as stark between female and male Protestant respondents. Both groups were substantially less likely than male Catholics to consider paramilitary groups as a source of safety.

Different perceptions of armed groups by gender are not unique to Northern Ireland. A 2014 study on Colombia found significant differences between female and male perceptions of post-conflict politics and participation. Although there were no substantial gender differences in the overall support for the peace process in Colombia, female respondents reported higher levels of distrust and skepticism toward demobilization, forgiveness, and reconciliation and higher disapproval of the political participation of former FARC members. The effect was even greater for mothers and women victimized during the conflict.

Violent attacks have dampened the anniversary celebration of the peace agreement and 25 years of relative stability. The recent injury of a police detective by an IRA splinter group, reports of paramilitary-style attacks and the use of petrol bombs against the police, coupled with turf battles between Ulster factions are continuous reminders of the presence and power that paramilitary organizations still hold across Northern Ireland. Even today, communities are kept under siege through violence and ransom. The formal termination of violent conflicts through peace agreements, as in the case of the Good Friday Agreement and other prominent examples such as the 2016 Colombian Peace Accord, does not automatically imply the disbandment of armed organizations. The impact of the presence of (former) armed groups in people’s daily lives continues to be high in most post-conflict contexts.

Findings from surveys in other post-conflict environments mirror this long shadow of war. A study of Croat and Serbian youths showed the continued impact of the Yugoslav Wars on ethnic group identities and how continued communal segregation impacts inter-group ethnic attitudes towards out-groups. A recent study finds that a decade after the civil war in Sri Lanka people from previously warring sides have very different views of peace and security. Respondents who belong to the defeated minority ethnic group, the Tamils, provided a more negative assessment of security and ethnic relations than those from the victorious majority, the Sinhalese. They also reported seeing irregular armed groups in a more protective role rather than a threatening one, when they encountered them, as we show here. And in many post-war countries, it’s the police who threaten peace, as discussed in this post. A study on Liberia found that experiences during the war continued to impact perceptions of the police afterwards. Victims of rebel violence were later more trusting of the police, while victims of state-perpetrated violence were not.

Much research is rightly concerned about how to avoid the conflict trap. Yet even countries that avoid falling back into full-scale civil war oftentimes do not offer adequate security and peace for all groups of their civilian population. Continued vigilance of unequal experiences and perceptions of security are necessary to work towards meaningful and lasting peace.

Sabine C. Carey is Professor of Political Science at University of Mannheim. Marcela Ibáñez is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Chair of Political Economy and Development at the University of Zurich. Eline Drury Løvlien is Associate Professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of Teacher Education.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) via the Collaborative Research Center 884 “Political Economy of Reforms” at the University of Mannheim.

. . . [Divine] Mercy is found even in the damnation of the condemned, for, while not completely loosening the punishment, It nonetheless lessens it short of what is entirely deserved. (Summa Theologiae Ia.21.4 ad 1).

I would like to address J. Daryl Charles’s argument published here at Public Discourse yesterday that the death penalty is a mandatory punishment for premeditated murder, necessary to achieve justice, and necessary to respect the image of God in the offender by holding him responsible for his acts. I cannot address everything that Charles argues in his essay. I will do only three things. First, I will argue that Charles has not and cannot successfully press the case that the use of the death penalty is mandatory in the exercise of punitive justice. Second, I will argue that it should be abolished in the United States, against the background of Thomas Aquinas’s argument (that Charles himself cites) that taking a criminal’s life is lawful in order to protect the common good. Third, I will conclude by reflecting on the implications of the image of God within us for justice and mercy.

The Early Church and Capital Punishment

On the first point, consider only the early Church figures that Charles cites. By and large, they do indeed recognize the legitimate authority of a political community to take the life of an offender. However, they also recognize something that Charles does not: it is within the state’s authority to refrain from this punishment and to instead extend mercy. (In this section, I summarize, paraphrase, and later quote the excellent article by Phillip M. Thompson, “Augustine and the Death Penalty,” in Augustinian Studies, January 2009, pp. 188–203.)

For example, Lactantius in one work forbids anyone in authority charged with the administration of justice from charging anyone for a capital crime, but in another acknowledges the state’s authority to put someone to death. Tertullian recognizes the authority of the state to impose death, and yet forbids any Christian from doing so. So also, the Christian author Athenagoras, whom Charles does not cite, forbids Christians from participating in it. This is not yet a point about mercy. However, it suggests a certain abhorrence on the part of the early Church for the death penalty as inconsistent with the life of a Christian. The secular or pagan state may be permitted to impose death as a punishment, but the authors suggest Christians ought to play no part in exercising that power.

The early Church figures recognized something that Charles does not: it is within the state’s authority to refrain from capital punishment and to instead extend mercy.

Augustine, however, is particularly important when it comes to mercy. He recognizes the authority of the state to impose death as a penalty, particularly to protect the common good from a threat to its safety. And he does not forbid Christians from participating in it, as others had. But he also pleads for mercy on the part of governing authority. In one case pleading for mercy he writes, “[W]e do not in any way approve the faults which we wish to see corrected, nor do we wish wrong-doing to go unpunished because we take pleasure in it. … [However,] it is easy and simple to hate evil men because they are evil, but uncommon and dutiful to love them because they are men.” Even if one does not agree with Augustine that one should love the offender because he is a man, as it seems Christ commanded us to do, Augustine gives evidence in the Christian community of the recognition that not only justice is the task of the state, but also that mercy is within the authority of the state, as much within its authority as is the authority to execute the offender.

However, the importance of mercy amid justice is no sectarian Christian virtue. The responsibility of governing authority to show mercy is a fact recognized by Seneca, no Christian, in his letter to Nero, De Clementia, where he argues that mercy in a ruler is essential to governing. As a stoic, however, his argument for mercy is significantly different from Augustine’s, focusing not on loving the offender as a fellow human being, but on the need to rein in both leaders’ and society’s passions of cruelty and savagery, passions that often accompany the just desire to punish. He goes on to argue that the power of the emperor to extend mercy is even greater and more manifest than is his power to condemn, “for anyone can take a life, but few can give it.” That power in a ruler is in fact godlike, according to Seneca. Aquinas agrees when he writes that among all of God’s attributes, it is in mercy that God’s omnipotence is most clearly shown. (“Unde et misereri ponitur proprium Deo, et in hoc maxime dicitur eius omnipotentia manifestari” ST IIaIIae 30.4.)

Just as one would be hard pressed to find a culture with a governing authority, biblical or otherwise, that had not at some point asserted and exercised the right to put capital offenders to death for heinous crimes, one would be equally hard pressed to find one that did not claim the authority to exercise mercy and punish short of death. Good government in the administration of criminal punishment will establish a range of possible punishments for a crime, acknowledging the need for both mercy and equity in judging which punishment is best in the circumstances. Again, this is a point recognized by the pagan Seneca, who argued that mercy does not come after the judgment of just punishment, to limit justice as it were, but enters into the determination of what justice is in a particular case.

Aquinas on Capital Punishment

Aquinas argues that this governing authority to establish the character of punishment and its application to cases is rooted in the natural law. But in the end, positive human law determines the actual force and scope of punishment. Any such “determination” of the actual punishment appropriate for a crime has only the force of human law, not the force of the natural law itself (ST IaIIae 95.2). We decide how crimes will be punished as a matter of human positive law, not by deriving them from natural law. This determination is part of our dignity as images of God: we participate in divine providence by being provident over ourselves. We use our reason both to recognize the natural law within us and to establish human law over diverse political communities and common goods (ST IaIIae 91).

In addition, like Seneca before him, Aquinas recognizes that it is also the task of judicial authority to exercise equity (epikeia) when determining punishment under human law. The judicial authority does this by taking into account circumstances not anticipated by the legislature when it crafted the law. In other words, judicial authority sets aside “the letter of the law,” lest one sin against the common good by application of the “letter of the law” (ST IIaIIae 120.1).

If we acknowledge Aquinas as an authority on these matters, as Charles seems to do in citing him, these points make it clear that it is well within the governing authority of a community to refrain from the use of the death penalty to punish crime. Political leaders can even refrain from legislating that capital punishment will be among the range of punishment for serious crimes, including premeditated murder. This decision ultimately requires reflection about how to preserve and promote the common good of a particular community in a particular place and time.

Political leaders can even refrain from legislating that capital punishment will be among the range of punishment for serious crimes, including premeditated murder.

A Case for Abolition

Now I would like to argue that the death penalty should be abolished, at least in the United States and many other nations as well. Of course, Aquinas’s argument about the lawfulness of a community’s taking the life of an offender is often cited by proponents of the death penalty in the way Charles cites it—as if permissibility requires the exercise of the death penalty in certain cases, that is, makes it “mandatory.” However, Aquinas’s argument is merely that it is lawful to take the life of an offender to protect the common good from threat. He does not come anywhere close to arguing that it is required or mandatory for certain crimes.

It is very important to notice about Aquinas’s argument that it is not based on principles of restitution, that is, not based on the need to redress the harm done to the one who has been wronged. Nothing can be done to redress the wrong done to the one who has been killed. Nothing can undo that, no recompense given, no restitution made. This is a point that Charles himself recognizes in the case of murder. In addition, though it might sound harsh, it is not the task of governing authority to criminally punish offenders in order to assuage the anguish of the family and friends of the murdered. Those left behind or affected by a murder may derive a certain amount of psychological catharsis in seeing the responsible parties punished, but it is probably not lasting. What’s more, in terms of restitution, nothing can undo what they have lost. That is in part the horror of the crimes done—that nothing can be done to restore to the one abused or to family and friends what has been taken from them. At best, punishment can be merely symbolic with respect to restitution in these cases.

Criminal law punishes not on behalf of the individuals who have been harmed by a crime, but on behalf of society’s common good, which has been harmed by a crime. It punishes to restore the order and peace of society that has been disturbed by the crime, and to further protect it from threat. But even here in the case of capital crimes, society cannot have restored to it what the crime has taken; society cannot have restored to it the human being killed. No punishment will return the order of tranquility and innocence lost to a society by the abuse of children, or to women and men by various forms of violence. However, a certain amount of peace and tranquility can be restored in protecting society from further threat of such things.

Close attention to Aquinas’s argument suggests that a malefactor loses, in a way proportionate to the gravity of the crime, the protections afforded by society to the innocent and thus becomes subject to the punishment of the law. This is its retributive aspect, that formally the gravity of the punishment is directed to the will of the offender in a way proportionate to the gravity of the crime willed by the offender. But, as we’ve seen above, the idea of “proportion” here is not a conclusion drawn from the natural law, but a “determination” of human law in light of the common good that punishment serves to protect. The offender becomes subject to the loss of property or the loss of freedom of movement, for example. Also, in some cases he becomes subject to the loss of life.

Aquinas’s argument is not that killing an offender is always lawful, much less that it is mandatory. It is lawful upon a condition, namely, that it is necessary to protect the common good from a threat.

What Aquinas does not argue, however, is that having become subject to punishment, even possibly the loss of life, a criminal’s loss of life is required or mandatory. It is not the so-called lex talionis—an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and a life for a life—that allows for the lawfulness of killing another human being. The lawfulness of ending an offender’s life is based on the need to protect society from the threat by the one who has lost the protection of society. So, one cannot claim that according to Aquinas the killing of a human being is lawful in order to pursue retribution or restitution for the wrong done. It is lawful to protect from harm, which is forward-looking, not backward-looking.

Thus, Aquinas’s argument is not that killing an offender is always lawful, much less that it is mandatory. It is lawful upon a condition, namely, that it is necessary to protect the common good from a threat. Absent that condition, Aquinas does not argue or even suggest that killing a malefactor, including one who has committed murder, is lawful. Indeed, in his discussion of clementia as mercy extended to those who are subject to punishment (ST IIaIIae 157.3 ad 1), he suggests that the desire to harm through punishment should be avoided and mitigated, even when someone deserves punishment. He also says that it is better when the one doing the punishing decides the wrongdoer has had enough, rather than pursue the full extent of punishment possible.

One can ask under what conditions governing powers should exercise mercy. The exercise of mercy ought also to take into account the common good. Aquinas’s argument that it is lawful to take the life of a malefactor to protect society from threat also suggests that mercy is legitimately exercised when no threat to the common good is posed by the offender. This would be the case when, for example, the offender can be rendered harmless to the common good by means other than killing. This point concerning the death penalty is made explicitly by Pope St. John Paul II in his encyclical Evangelium Vitae.

In the thirteenth century when Aquinas made his argument, it might not have been possible in general to render a murderous malefactor harmless short of killing him. However, it is now possible in the United States and many other modern nations to protect the common good from the threat of those who have committed murder and other heinous crimes. That being the case, we have no reason to think that it is lawful for those nations to kill human beings who in other times and places might pose a threat to the common good. Given the imperative to act with mercy as much as with justice, the death penalty ought thus to be abolished in the United States and other such countries.

It is now possible in the United States and many other modern nations to protect the common good from the threat of those who have committed murder and other heinous crimes.

Mercy and Justice

To conclude, Charles makes much of the idea that the image of God in human beings is not taken seriously if we do not hold offenders responsible for their crimes, particularly those who have killed with premeditation. I agree with that proposition. What Charles and other defenders of the death penalty do not take seriously enough is the thought that being made to the image and likeness of God is not a static fact of human nature, but a responsibility. Nothing can erase from the nature of a human being the image created within him or her by God, no sin or crime however heinous. We acknowledge that fact when we hold our fellow human beings and ourselves responsible for our actions. However, being made to the image of God is a vocation, that is, a call to being godlike in all that we do. So, those of us who seek justice in the punishment of others must ask ourselves what our godlike responsibility is in the circumstances in which we live.

God is not simply a God of justice, but also a God of mercy. Mercy and justice are not set against one another. As Aquinas argues, they are manifest in every act of God’s (ST Ia 21.4). Even so, divine justice is founded upon divine mercy. Even the pagan Seneca recognized that mercy is as godlike as justice. In addition, mercy is not a poor second cousin to justice. Again, Aquinas argues that among human virtues, mercy is the greatest of all virtues, greater even than justice (ST IIaIIae 30.4). Mercy does not come in after justice to limit it. Mercy informs justice. Indeed, if we take Aquinas seriously, justice strives after mercy as its goal. “It is clear that mercy does not take away justice, but is in a certain way, the plenitude of it” (Ia 21.3 ad 2). Justice must always then be informed by mercy. After all, with the responsibility to live up to the image of God within us, it is worth pondering the fact that not even the damned in Hell are punished by God as much as justice alone might allow that they deserve. How much more, then, should punishment be loosened for those among us who have not yet been damned?

Today’s essay by Daryl Charles makes the case for capital punishment for those guilty of premeditated murder. Tomorrow’s essay will be a reply by John O’Callaghan, who argues for the abolition of the death penalty.

Our culture is morally confused about many things. Conservative Christians tend to focus on concerns about hot button issues like abortion, sexuality, relativism, and education. But one phenomenon that is overlooked but no less urgent is murder. A mere listing of mass killings occurring in the United States in recent years boggles the mind. The year 2022 alone, by all counts, surely must be record-setting. As I write (early October of 2022), one reads that a fifteen-year-old in Raleigh, North Carolina goes on a shooting spree, killing five (including his brother and an off-duty police officer) as he walks through a neighborhood; that five people have been shot in a northern South Carolina home; that in Bristol, Connecticut, two police officers are fatally shot and a third wounded in responding to a domestic violence call (which is said to have been a ploy to lure the officers); and that a thirty-two-year-old is charged with two counts of murder and six of attempted murder following a stabbing melee on the Las Vegas Strip. In the same week we read that four bodies have been found in the Oklahoma River. And this just in: a Florida jury recommends a life sentence without parole instead of the death penalty for the man who murdered seventeen people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018.

These randomly selected tragedies, of course, only identify the tip of the iceberg. Most of our cities are currently reeling from the sheer frequency of killings that have descended on our streets, our neighborhoods, our families, and even our schools. In the four months of June, July, August, and September of 2022, there were respectively 73, 100, 71, and 70 mass shootings, with the total numbers of injured or dead being 297, 439, 262, and 272 respectively. Tucked away in these numbers are the horrendous tragedies and suffering that have visited communities such as Orlando, Uvalde, and Buffalo. According to the Marshall Project, more mass shootings (i.e., of four or more victims) have occurred in the last five years than in any other half decade since 1966.

On the rare occasions when the death penalty is discussed today, it is almost always viewed unfavorably.

The barbarism behind increasing murder rates suggests that debates over capital punishment should intensify. But this has not been the case. In fact, what is striking is the relative absence of discussion and debate of the death penalty. On the rare occasions when the death penalty is discussed today, it is almost always viewed unfavorably. The abolitionist argument takes any number of forms: the mental health of the murderer; the possibility of prematurely ending a criminal’s rehabilitation; debates over deterrence; the misconstruction of retribution as revenge (i.e., retributivism); fallibility of the criminal justice system; and modern notions of “civility.” Religiously motivated abolitionists sometimes point to the annulment of the Mosaic code, assumed ethical discontinuity between the Old and New Testaments; and Christ’s teaching on forgiveness.

We have grown intolerant of meting out punishment that is perceived as “cruel” or “barbaric.” Strangely, however, our abhorrence of penal “barbarity” is displayed against the backdrop of increasingly barbaric criminal acts themselves. Indeed, until very recently, capital punishment was almost universally affirmed biblically, morally, and legally.

Christian History and Capital Punishment

Even though abolitionist arguments have been dominant in recent decades, it is worth recalling that for most of history, a variety of civilizations have used the death penalty and grounded it in serious moral reflection. Capital punishment was practiced in the earliest recorded history. Its prescription appears in the mid-eighteenth-century-BC Code of Hammurabi, in sixteenth-century-BC Assyrian codes, in fifteenth-century-BC Hittite codes, in the thirteenth-century Mosaic Code, as well as in ancient Greek and Roman law.

Among the church fathers, one finds varying perspectives on the death penalty, although there is a general recognition of the state’s responsibility to implement capital justice. Tertullian (late second century) and Lactantius (late third century) affirmed that in the case of murder divine law consistently required a life for a life. Both Augustine (late fourth and early fifth century) and Theodosius II (mid-fifth century) acknowledged the state’s role in mediating capital sanctions. In addition, various councils from the seventh century (the Eleventh Council of Toledo) to the thirteenth (the Fourth Lateran Council) followed the lead of Leo the Great (fifth century) in forbidding clerics from engagement in matters of capital justice, even as they understood the state’s legitimate role in facilitating such matters.

It is worth recalling that for most of history, a variety of civilizations have used the death penalty and grounded it in serious moral reflection.

In the Summa Contra Gentiles, Aquinas insisted that the community had both the right and the duty to “cut away” an individual in order “to safeguard the common good.” The common good, he reasoned, is “better than the good of the individual,” notably because “certain pestilent fellows” who serve as “a hindrance to the common good, that is, to the concord of human society.” Such persons, he concluded, therefore “are to be withdrawn by death from the society of men.”

Late medieval and Reformation-era theologians also affirmed the state’s duty before God to impose capital sanctions upon murderers. Even the so-called “left wing” of the Protestant reform movement—from which much modern religious opposition to capital punishment is thought to derive—recognized the death penalty. The Schleitheim Confession of 1527, an exemplary document adopted by the Swiss Brethren (the progenitors of earliest Anabaptism), reads: “The sword is an ordinance of God. … Princes and Rulers are ordained for the punishment of evildoers and putting them to death.” This Anabaptist declaration concurs with the 1580 Lutheran Formula of Concord, which prescribes for “wild and intractable men” a commensurate “external punishment.” In summary, the patristic, medieval, and late medieval periods generally mirror the church’s tacit acknowledgment of capital punishment in cases of murder.

There has been much debate about the place of capital punishment in Catholic social thought, but the pre-2018 version of the Catechism of the Catholic Church articulates the most sound position on the topic:

Preserving the common good of society requires rendering the aggressor unable to inflict harm. For this reason the traditional teaching of the Church has acknowledged as well-founded the right and duty of legitimate public authority to punish malefactors by means of penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime, not excluding, in cases of extreme gravity, the death penalty. (no. 2266, emphasis added)

The Church’s teaching on the death penalty historically finds expression in Thomas Aquinas’s question “Is it legitimate to kill sinners?” (S.T. II-II, Q. 64.2). His response is predicated on “the common good,” with an analogy. If the well-being of the whole physical body requires the amputation of a limb, the treatment is to be commended. “Therefore if any man is dangerous to the community and is subverting it by some sin, the treatment to be commended is his execution in order to preserve the common good, for a little leaven sours the whole lump.” What is forbidden, Aquinas argues later, is to take the life of an innocent person (Q. 64.6).

Theological Arguments

It is no surprise that for most of Christian history, the death penalty was widely embraced. To understand the theological basis for capital punishment, we must first look to the nature of law. Fundamental to the biblical story is the depiction of the Creator as Lawgiver. Law, as the reader of the biblical narrative discovers, is of no human origin, nor does it issue out of pragmatic or popular consent. Its authority issues not out of cultural or intellectual enlightenment but from the universal created order. Whether individual cultures and regimes recognize this reality is, of course, another matter. Yet the effects of moral law are as the law of gravity: its disregard always and everywhere results in the rotting of social culture.

In a remarkable—though little remembered—series of homilies in 1976 (eventually published under the title Sign of Contradiction), Karol Wojtyła, at the time Archbishop of Cracow, delivered a sustained reflection on the question of man’s purification from sin in the present life. Guilt incurred by sin, he observed, constitutes a debt in the present order that must be paid. Punitive dealings, thus, provide necessary atonement and restore the balance of justice and moral order that has been disturbed. In theological terms, they prepare the human being for a destiny in eternity.

Punitive dealings provide necessary atonement and restore the balance of justice and moral order that has been disturbed.

In Sign of Contradiction, we find the necessary response to religious abolitionists who ground their bias against capital punishment in a particular (mis)reading of Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount and a purported “forgiveness” ethic. Pitting a misinterpreted Jesus against Paul, they ignore ethical continuity in the broader sweep of biblical revelation and prefer, based on the flaws of human government, to dismiss its divinely instituted commission to punish evil and reward good.

This defect in religious thinking—“the cross is not a sword”—demonstrates conspicuous disregard for what is recorded in the text of Genesis 9, where God makes his covenant with Noah after the flood, the implications of which are stated in universal terms. It is precisely because the human being is fashioned in the image of God that one who purposely sheds the blood of another must die. Genesis 9:5–6 is to be understood foremost as an institution that protects life, in accordance with the Decalogue’s pronouncement “Thou shalt not murder.” The rationale for this morale imperative is none other than the safeguarding of human life. Retribution discourages invasions on the sanctity of the human creature. (Here let us pause for a moment: any society that advances an “inversion ethic” of killing human beings in utero while refusing to take the life of a convicted murderer should strike us as barbaric.) The Genesis narrative suggests that premeditated murder is an assault on human life and is comparable, as it were, to an assault on the very being of God. The fact that justice demands punishment befitting the crime—i.e., just retribution—reveals the essential difference in character between revenge and retribution.

Having been created in the imago Dei, human life is a sacred trust. The implication is clear: murder—i.e., the deliberate extermination of a life by another human being—is tantamount to killing God in effigy. Moreover, as confirmed in Mosaic legislation, premeditated murder is the one crime for which there exists no restitution. As C. S. Lewis noted in his wonderfully prescient essay, “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” to be punished however severely because we in fact deserve it is to be treated as a human being created in the very image of God.

Justice, Charity, and Restitution

When a murder occurs in our community, we are obliged, regardless of our comfort level, to clear our throat as it were and make a public, communal declaration. The deliberate extermination of another human being is an absolute evil and therefore absolutely intolerable. Period. This was the argument advanced by David Gelernter in a 1998 Commentary essay. Gelernter, a professor of computer science at Yale who was letter-bombed in June of 1993, almost lost his life. The essence of Gelernter’s argument was that we execute murderers in order to make a communal statement: deliberate murder embodies evil so terrible that it defiles the community, and as a result the community needs catharsis that occurs through criminal justice properly construed. Gelernter correctly noted that in the face of murder, contemporary society, however, is more prone to shrug it off than to exact just retribution and affirm binding moral standards.

In the case of premeditated murder, compensation is not available. Hence, as much of human history attests and as the biblical witness affirms, it is the one crime that carries a mandatory death sentence.

Justice has classically been defined as rendering to each person what is due. Desert, then, is foundational to ethics; it is a part of the human moral intuition. Parents know this, children know it, and indeed people from Kansas to Canada to Kenya to Kazakhstan know it as well. Retributive justice, then, is a social good, for it corrects social imbalances and perversions. Herein we find the wedding of justice and charity. When through social attitudes and the rule of law we affirm retributive justice, we are addressing several levels of “imbalance” and disturbance: we are attentive to (1) the victimized party who has been wronged, (2) society at large, which has been offended and is watching, and (3) future offenders who might be tempted to do evil. This trifold application of justice, as Augustine and Aquinas understood it, was in fact an application of charity. And as an extreme example, both saw going to war as an act that can express the wedding of charity and justice properly construed: it is charitable to prevent the criminal (whether domestically or in war) from doing evil, and it is charitable toward society, which needs protecting.

Punishment for a crime and restitution for the victim are interrelated concepts. In the case of premeditated murder, compensation is not available. Hence, as much of human history attests and as the biblical witness affirms, it is the one crime that carries a mandatory death sentence. To suggest or argue that the ultimate human crime should not be met with the ultimate punishment being meted out by civil authorities, at least in a relatively free society, is not some “higher” ethic as some might contend; nor is it “Christian” by any stretch of the imagination. Rather, it is a moral travesty because it fails to comprehend the nature and meaning of the imago Dei.

Civilized societies do not tolerate the murder of innocent human beings; uncivilized regimes do.

Georges Bernanos, the great French writer, had a particular distaste for the cult of optimism, especially its American variety. The idea that things somehow, naturally, turn out for the better struck him as laughably deluded, a form of “whistling past the graveyard.” In the real world, things often don’t turn out for the better. They get worse. And the graveyard can’t be ignored away, because death is real. We all sooner or later face it, and no amount of whistling will help us sneak past it. So how a culture deals with death speaks volumes about its mental health—and its understanding of who and what a human being is.

I turned 70 four years ago. Shortly thereafter I informed my family that I’ll be very displeased, despite being dead, if the priest at my funeral wears anything but black. They weren’t surprised. In the Catholic tradition, liturgical vestments have a catechetical role. They give meaning to the moment. Green is for Ordinary Time and the virtue of hope. Red is for Pentecost, the fire of the Holy Spirit, and the blood of martyrs. White, and occasionally gold, reflect the glory of the Christmas and Easter seasons, solemnities, and the great feasts. Purple is penitential for Lent and anticipative for Advent, and the color rose—hinting at the joy to come—is used on Advent’s Gaudete and Lent’s Laetare Sundays.

This “curriculum of color” in Catholic worship, like the annual progress of the Church calendar, has always made deep sense to me, mirroring the course of life itself. What doesn’t make sense is the absence of black today at exactly the emotional and religious event that most profoundly needs it. Since Vatican II, most Catholic funerals have been celebrated with white vestments, or the alternative, purple. Black vestments are still a legitimate option, but—at least in the United States, where optimists are (or until recently, were) the dominant sect—they’re rarely used. Many parishes no longer have them.

This is instructive. The reasoning for black’s exile goes something like this: white encourages trust in God’s love and mercy for the deceased. Purple communicates grief, but not fear. Black, on the other hand, is a downer; a hammer that drives home the nail of loss. And yet, ironically, this also makes it the sanest, most powerful, of funeral colors. It acknowledges the pain of mourning as necessary to healing, and it implicitly reminds us that an immediate, happy eternity is in nobody’s automatic “win” column. If white implies a freeway diamond lane past any afterlife unpleasantness, black reminds us that many of us will be stuck in traffic. Some of us for a long time—or worse. Which suggests two important facts: that the deceased needs our prayers, and that our own lives, and their content, will be judged in due course by a God who is not only merciful, but also just.

Most Catholics and other Christians will understand the argument I’ve just made, even if they disagree with the particulars. Death is a universal fact of life, but as Charles Chaput, borrowing from the philosopher Hans Jonas, noted some years ago, man is the only creature, among all living things, that knows he must die: “No other species buries or remembers its dead as we do. The grave is a uniquely human fact. It reminds us that we’re not like other animals. Thus, repudiating the grave implicitly denies our distinctive humanity by denying one of its most important markers.”

Death has emotional “weight” because every human life is woven into a fabric of other conscious, intentional lives and loves. The loss of the individual matters to those others in a singular way. Death also has a sacred aura because, for the religious believer, each human life is unique and unrepeatable, with a God-given dignity. And the human body, especially for Christians, is not an irrelevant husk of the departed soul. It’s an essential element of his or her personhood, destined to one day rise again. Funeral liturgies are thus as much for the living as they are for the dead. They remind us of the type of creature we are; that life has purpose; and that the grave is not the end. As Jonas wrote, “metaphysics arises from graves.” Or to put it another way: the grave anchors us to reality; the reality of loss in this world, and the reality—or at least the promise—of unending life in the next.

Death also has a sacred aura because, for the religious believer, each human life is unique and unrepeatable, with a God-given dignity.

Death in a Secular Age

Now having said all of the above, consider the following.

The country I grew up in no longer exists. The late Paul Johnson said that America was born Protestant. And while scores of millions of us still practice some form of a biblical faith, it’s more accurate to say that America was born from a marriage of Bible-based belief and Enlightenment thought. Mixed marriages can survive and thrive, and many do—but only if the partners are truly compatible, and stay that way. The original brand of American Christianity was rigorously Calvinist. As the philosopher George Parkin Grant argued in Technology and Empire, the nature of Calvinist theology “made it immensely open [to] empiricism and utilitarianism,” resulting in a religion of material progress marked by “practical optimism” and “discarded awe.” Translation: we’re a pragmatic people. We’re addicted to technological mastery. And our real faith—no matter how we label ourselves—is a practical agnosticism focused radically on this world. In effect, we’re becoming the most thoroughly materialist culture in history.

This has shaped American attitudes toward death in different ways. Serving the needs of the deceased, and surviving family members, with compassion and dignity is a noble vocation. For Christians, it’s one of the seven “corporal works of mercy.” But it can also be a lucrative line of work, because there’s no lack of customers. Jessica Mitford’s 1963 book, The American Way of Death, attacked the funeral industry of her day for its greed and phony piety. Terry Southern did the same in The Loved One, a fiercely satirical 1965 film based on the Evelyn Waugh novel.

But that was then. Feelings toward death today reflect the more secularized, irreligious nature of the country. High-end caskets have lost some of their luster. Cremation is common. The afterlife is often viewed as a fantasy, or a guaranteed Happy Place with furniture provided by a person’s private beliefs.

Some grieving survivors have taken to scattering the ashes of a deceased loved one in a place of special meaning. In an age when green is especially good, and environmentalism can verge on the cultic, “human composting” is increasingly available. After all, why not feed Mother Nature with the rich nutrients of your decomposing corpse? And it’s attractively priced: currently at $5,500 or less. But these low-tech approaches have an unsatisfying, romantic-theatrical feel to them. The real experts know, or think they know, that the best way to deal with death is to simply kill it.

The afterlife is often viewed as a fantasy, or a guaranteed Happy Place with furniture provided by a person’s private beliefs.

Denying Death

Futurists like Ray Kurzweil claim that we’re just a few scientific steps away from achieving immortality. The biotech company Calico Life Sciences focuses on extending human longevity and defeating age-related disease. Other research seeks to copy a person’s identity via memory chip, and then transfer it to new bodies as old ones wear out. The Cryonics Institute offers prompt cryogenic suspension and long-term storage for victims of terminal illness. For the low, low, price of $28,000, a person can be frozen in the hope that, in the future, he or she can be revived and healed with new nano-technologies. Other companies offer similar cryo-options at price tags up to $200,000, with an economy version for the head only. And yet Leon Kass, the great Jewish bioethicist, has repeatedly asked the essential question: why would any sane person want to live another century, or five, or forever in this world, even under the best circumstances?

Survival is an end in itself only in the short term. An endless life of consuming and digesting successive experiences isn’t a “human” life at all. We have an instinctive hunger for higher meaning; for a shared purpose beyond ourselves. Without it, even cocooned in luxury, even with our senses anesthetized by noise and distractions, we end in despair. Yet this is exactly what American culture now breeds, which is why our rates of depression, mental illness, and drug use continue to climb. Even suicide can seem to make terrifying sense. Why stick around if this is all there is? Scattering ashes, human composting, radical longevity extension, cryogenic suspension: these all, in their own odd ways, involve a kind of self-delusion that masks unacknowledged, unhealable emptiness. They’re blind to what death at the end of a good life, well lived, actually is: the doorway to something greater.

An endless life of consuming and digesting successive experiences isn’t a “human” life at all. We have an instinctive hunger for higher meaning; for a shared purpose beyond ourselves.

In his letters, J. R. R. Tolkien wrote that the real theme of Lord of the Rings is death and immortality; that attempts to artificially prolong life in this world are a trick of the Evil One; that we’re made for another home; and that one of God’s great gifts to men “is mortality; freedom from the circles of the world.” Simply put: we’re more than clever primates with a gift for telling tall tales about some Sugar Candy Mountain in an afterlife. One of the tales is true.

I suppose what I’m saying here is simply this: all those we love, and we ourselves, will one day go through that great black door of death. We need to acknowledge that fact and not try to evade or soften it. Without God, life really is a tragedy, and our mourning is a meaningless biochemical reaction. But our story doesn’t end there. The door has another side: a side of light, with a waiting, loving God. That’s why I can write these thoughts and sleep very well tonight—although I do hope that if my pastor ever reads this, he’ll buy some black vestments. I’ll gladly kick in on the cost. Because black is beautiful.

There are few images of the modern world more powerful than that of the humbled Galileo, kneeling before the cardinals of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition, being forced to admit that the Earth did not move. The story is familiar: that Galileo represents science fighting to free itself from the clutches of blind faith, biblical literalism, and superstition. The story has fascinated generations, from the philosophes of the Enlightenment to scholars and politicians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The specter of the Catholic Church’s condemnation of Galileo continues to influence the modern world’s understanding of the relationship between religion and science. In October 1992, Pope John Paul II appeared before the Pontifical Academy of the Sciences to accept formally the findings of a commission tasked with historical, scientific, and theological inquiry into the Inquisition’s treatment of Galileo. The Pope noted that the theologians of the Inquisition who condemned Galileo failed to distinguish properly between particular biblical interpretations and questions pertaining to scientific investigation.

The Pope also observed that one of the unfortunate consequences of Galileo’s condemnation was that it has been used to reinforce the myth of an incompatibility between faith and science. That such a myth is alive and well was immediately apparent in the way the American press described the event in the Vatican. The headline on the front page of The New York Times was representative: “After 350 Years, Vatican Says Galileo Was Right: It Moves.” Other newspapers, as well as radio and television networks, repeated essentially the same claim.

The New York Times story is an excellent example of the persistence and power of the myths surrounding the Galileo affair. The newspaper claimed that the Pope’s address would “rectify one of the Church’s most infamous wrongs—the persecution of the Italian astronomer and physicist for proving the Earth moves about the Sun.” For some, the story of Galileo serves as evidence for the view that the Church has been hostile to science, and the view that the Church once taught what it now denies, namely, that the Earth does not move. Some take it as evidence that teachings of the Church on matters of sexual morality or of women’s ordination to the priesthood are, in principle, changeable. The “reformability” of such teachings is, thus, the real lesson of the “Galileo Affair.”

But modern treatments of the affair not only miss key context surrounding the Inquisition’s condemnation of Galileo; they also misinterpret what the Catholic Church has always taught about faith, science, and their fundamental complementarity.

For some, the story of Galileo serves as evidence for the view that the Church has been hostile to science, and the view that the Church once taught what it now denies, namely, that the Earth does not move.

Galileo and the Inquisition in the Seventeenth Century

Galileo’s telescopic observations convinced him that Copernicus was correct. In 1610, Galileo’s first astronomical treatise, The Starry Messenger, reported his discoveries that the Milky Way consists of innumerable stars, that the moon has mountains, and that Jupiter has four satellites. Subsequently, he discovered the phases of Venus and spots on the surface of the sun. He named the moons of Jupiter the “Medicean Stars” and was rewarded by Cosimo de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, with appointment as chief mathematician and philosopher at the Duke’s court in Florence. Galileo relied on these telescopic discoveries, and arguments derived from them, to bolster public defense of Copernicus’s thesis that the Earth and the other planets revolve about the sun.

When we speak of Galileo’s defense of the thesis that the Earth moves, we must be especially careful to distinguish between arguments in favor of a position and arguments that prove a position to be true. Despite the claims of The New York Times, Galileo did not prove that the Earth moves about the sun. In fact, Galileo and the theologians of the Inquisition alike accepted the prevailing Aristotelian ideal of scientific demonstration, which required that science be sure and certain knowledge, different in some ways from what we today accept as scientific. Furthermore, to refute the geocentric astronomy of Ptolemy and Aristotle is not the same as to demonstrate that the Earth moves. Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), for example, had created another account of the heavens. He argued that all the planets revolved about the sun, which itself revolved about a stationary Earth. In fact, Galileo himself did not think that his astronomical observations provided sufficient evidence to prove that the Earth moves, although he did think that they called Ptolemaic geocentric astronomy into question. Galileo hoped eventually to argue from the fact of ocean tides to the double motion of the Earth as the only possible cause, but he did not succeed.

When we speak of Galileo’s defense of the thesis that the Earth moves, we must be especially careful to distinguish between arguments in favor of a position and arguments that prove a position to be true.

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, Jesuit theologian and member of the Inquisition, told Galileo in 1615 that if there were a true demonstration for the motion of the Earth, then the Church would have to abandon its traditional reading of those passages in the Bible that appeared to be contrary. But in the absence of such a demonstration (and especially in the midst of the controversies of the Protestant Reformation), the Cardinal urged prudence: treat Copernican astronomy simply as a hypothetical model that accounts for the observed phenomena. It was not Church doctrine that the Earth did not move. If the Cardinal had thought that the immobility of the Earth were a matter of faith, he could not argue, as he did, that it might be possible to demonstrate that the Earth does move.

The theologians of the Inquisition and Galileo adhered to the ancient Catholic principle that, since God is the author of all truth, the truths of science and the truths of revelation cannot contradict one another. In 1616, when the Inquisition ordered Galileo not to hold or to defend Copernican astronomy, there was no demonstration for the motion of the Earth. Galileo expected that there would be such a demonstration; the theologians did not. It seemed obvious to the theologians in Rome that the Earth did not move and, since the Bible does not contradict the truths of nature, the theologians concluded that the Bible also affirms that the Earth does not move. The Inquisition was concerned that the new astronomy seemed to threaten the truth of Scripture and the authority of the Catholic Church to be its authentic interpreter.

The Inquisition did not think that it was requiring Galileo to choose between faith and science. Nor, in the absence of scientific knowledge for the motion of the Earth, would Galileo have thought that he was being asked to make such a choice. Again, both Galileo and the Inquisition thought that science was absolutely certain knowledge, guaranteed by rigorous demonstrations. Being convinced that the Earth moves is different from knowing that it moves.

The disciplinary decree of the Inquisition was unwise and imprudent. But the Inquisition was subordinating scriptural interpretation to a scientific theory, geocentric cosmology, that would eventually be rejected. Subjecting scriptural interpretation to scientific theory is just the opposite of the subjection of science to religious faith!

In 1632, Galileo published his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, in which he supported the Copernican “world system.” As a result, Galileo was charged with disobeying the 1616 injunction not to defend Copernican astronomy. The Inquisition’s injunction, however ill‑advised, only makes sense if we recognize that the Inquisition saw no possibility of a conflict between science and religion, both properly understood. Thus, in 1633, the Inquisition, to ensure Galileo’s obedience, required that he publicly and formally affirm that the Earth does not move. Galileo, however reluctantly, acquiesced.

From beginning to end, the Inquisition’s actions were disciplinary, not dogmatic, although they were based on the erroneous notion that it was heretical to claim that the Earth moves. Erroneous notions remain only notions; opinions of theologians are not the same as Christian doctrine. The error the Church made in dealing with Galileo was an error in judgment. The Inquisition was wrong to discipline Galileo, but discipline is not dogma.

The Inquisition did not think that it was requiring Galileo to choose between faith and science. Nor, in the absence of scientific knowledge for the motion of the Earth, would Galileo have thought that he was being asked to make such a choice.

The Development of the Legend of Galileo

The mythic view of the Galileo affair as a central chapter in the warfare between science and religion became prominent during debates in the late nineteenth century over Darwin’s theory of evolution. In the United States, Andrew Dickson White’s History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896) enshrined what has become a historical orthodoxy difficult to dislodge. White used Galileo’s “persecution” as an ideological tool in his attack on the religious opponents of evolution. Since it was so obvious by the late nineteenth century that Galileo was right, it was useful to see him as the great champion of science against the forces of dogmatic religion. The supporters of evolution were seen as nineteenth-century Galileos; the opponents of evolution were seen as modern inquisitors. The Galileo affair was also used to oppose claims about papal infallibility, formally affirmed by the First Vatican Council in 1870. As White observed: had not two popes (Paul V in 1616 and Urban VIII in 1633) officially declared that the Earth does not move?

The persistence of the legend of Galileo, and of the image of “warfare” between science and religion, has played a central role in the modern world’s understanding of what it means to be modern. Even today the legend of Galileo serves as an ideological weapon in debates about the relationship between science and religion. It is precisely because the legend has been such an effective weapon that it has persisted.

Galileo and the Inquisition shared common first principles about the nature of scientific truth and the complementarity between science and religion.

For example, a discussion in bioethics from several years ago drew on the myths of the Galileo affair. In March 1987, when the Catholic Church published condemnations of in vitro fertilization, surrogate motherhood, and fetal experimentation, there appeared a page of cartoons in one of Rome’s major newspapers, La Repubblica, with the headline: ‘In Vitro Veritas.’ In one of the cartoons, two bishops are standing next to a telescope, and in the distant night sky, in addition to Saturn and the Moon, there are dozens of test-tubes. One bishop turns to the other, who is in front of the telescope, and asks: “This time what should we do? Should we look or not?” The historical reference to Galileo was clear.

In fact, at a press conference at the Vatican, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was asked whether he thought the Church’s response to the new biology would not result in another “Galileo affair.” The Cardinal smiled, perhaps realizing the persistent power—at least in the popular imagination—of the story of Galileo’s encounter with the Inquisition more than 350 years before. The Vatican office that Cardinal Ratzinger was then the head of, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, is the direct successor to the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition into Heretical Depravity.