Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

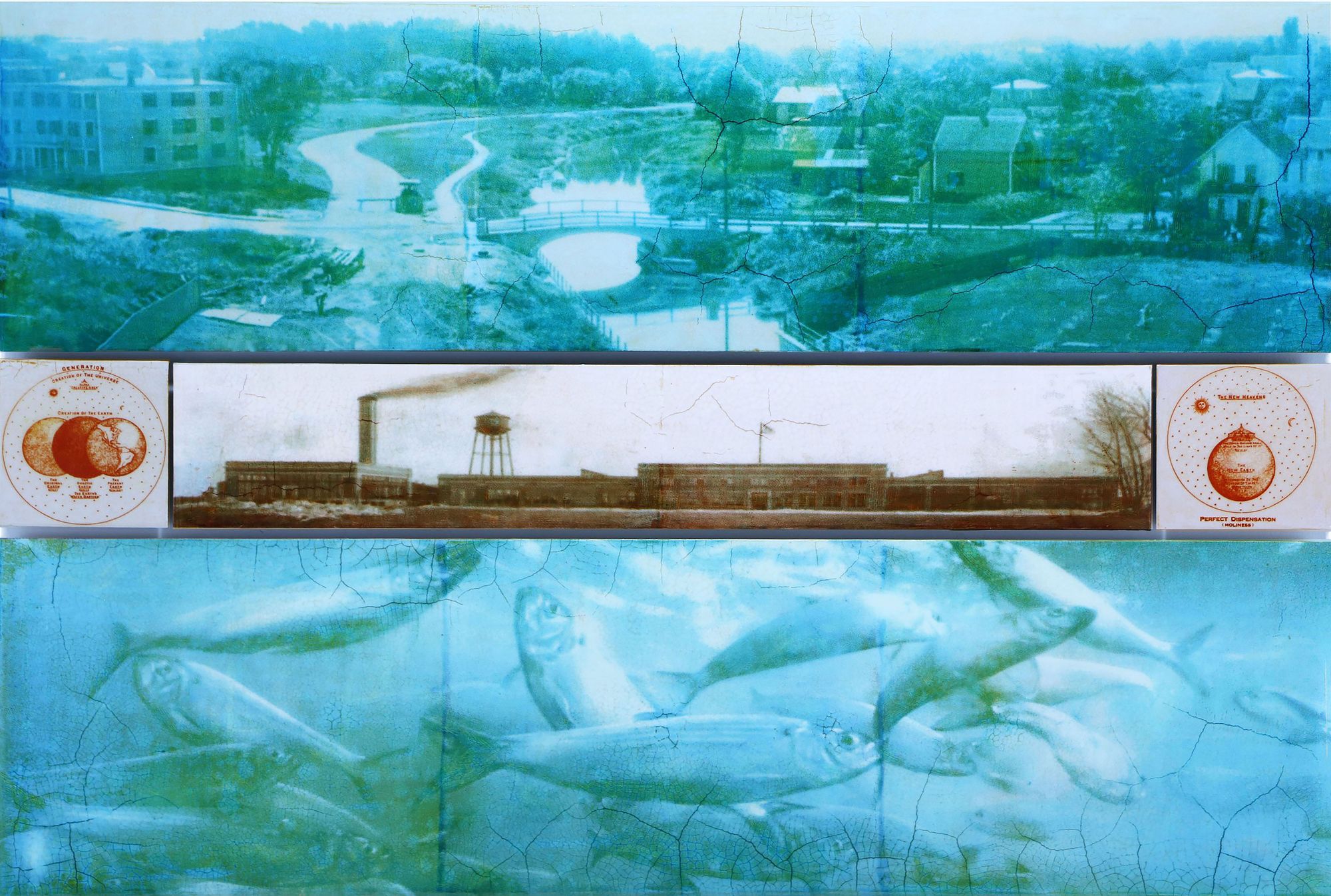

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

In his Histories, Herodotus tells the story of Croesus, a wealthy king who ruled the region of Lydia some 2,500 years ago. One day, Croesus consulted the famous oracle at Delphi about his conflict with the neighboring Persians. The oracle responded that if Croesus went to war, he would destroy a great empire. Sure of victory, Croesus marched for battle. Much to his surprise, however, he lost. The great empire he destroyed was not his enemies’, but his own. A few centuries later, the Persians were in turn bested by Alexander the Great.

Civilizations rise and fall, sometimes at the stroke of a sword. Myriad explanations have been posited as to why this happens. Often, hypotheses of collapse say more about the preoccupations of contemporary society than they do about the past. It is no coincidence that Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (01776), written during the anticlerical Age of Reason, blamed Christianity for Rome’s downfall, just as it is no coincidence that recent popular accounts of civilizational collapse such as Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (02005) point toward environmental damage and climate change as the main culprits.

I’ve been fascinated by the oscillations of human societies ever since the early days of my research for my Ph.D. in archaeology. Over the last 12,000 years, we’ve gone from small hunter-gatherer groups to highly urbanized communities and industrialized nation-states in a globally interconnected world. As societies grow, they expand in territory, produce economic growth, technological innovation, and social stratification. How does this happen, and why? And is collapse inevitable? The answers provided by archeology were unsatisfying. So I looked elsewhere.

Ultimately, I settled on a radically different framework to explore these questions: the field of complexity theory. Emerging from profound cross-disciplinary frustrations with reductionism, complexity theory aims to understand the properties and behavior of complex systems (including the human brain, ecosystems, cities and societies) through the exploration of their generative patterns, dynamics, and interactions.

In what follows, I’ll share some thoughts about what social complexity is, how it develops, and why it provides a more comprehensive account of societal change than the traditional evolutionary approaches that permeate archeology. By recasting the rise and fall of civilizations in terms of social complexity, we can better understand not only the past of human societies, but their possible futures as well.

In the 19th century, scholars like the sociologist Herbert Spencer and anthropologist Lewis Morgan became interested in the historical development of societies. They found a suitable explanatory framework in the principles of biological evolution as posited by Charles Darwin. Social evolution holds that human groups undergo directed processes of change driven by fitness adaptations to external circumstances, resulting in an inherent tendency to increase complexity over time. The phrase “survival of the fittest,” often attributed to Darwin, was coined by Herbert Spencer to describe the evolutionary struggles of societies. Social evolutionists conceptualized historical change as part of a teleological trajectory towards higher stages of social complexity. They believed complex societies to be the most successful. “Complex” entailed more developed rationality, philosophy, and morality. It meant, in short, more civilized. This notion of successful societies was appropriated and embedded in a wider framework of Eurocentrism and Western superiority to place Western nation-states at the pinnacle of human evolution and to provide a justification for colonialism (Morris, 02013, p.2).

During the second half of the 20th century, a neo-evolutionary resurgence resulted in the postulation of societal stages of development that are still in vogue today, such as Elman Service’s scheme of bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states (Service, 01962). While these works abandoned teleological notions, the identification of distinct developmental stages implies that fundamental properties co-occur in societies across time and space. It also suggests that societies stay in equilibrium until they go through a sudden phase shift and rapidly adopt a new set of properties and characteristics.

These assumptions are problematic in two ways. First, societal properties do not necessarily co-evolve, even if societal trajectories can converge to varying degrees due to similar underlying drivers (Auban, Martin and Barton, 02013, p.34). Second, equilibrium-based approaches are inherently static because they assume that changes cancel each other out over the long term. As a result, they regard change as ‘‘noise’’ that must be filtered out to understand the system. These approaches frequently employ reductionist views. This means identifying distinct subsystems, figuring out how these subsystems work, and then aggregating them to understand the behavior of the overall system. In human societies, that could mean identifying a separate economic system, then setting forth to understand that economy, while doing the same for other subsystems like politics, religion, and so on. Finally, by combining the understanding of each subsystem, we come to an understanding of society as a whole. Such top-down, reductionist approaches have strong limitations, as system behavior is not the result of the aggregation of the properties of its components, but rather the result of entirely new properties emerging in a bottom-up fashion. In other words, we must realize that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.”

Since the 01970s, scholars from a broad range of disciplines, including biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, systems theory and cybernetics, have been grappling with non-linearity, feedback loops, and adaptation across many kinds of systems, giving rise to the new field of complexity theory. Complex systems thinking posits that the fundamental units of social systems are social interactions between people. These interactions generate complex behavior, information processing, adaptation, and non-linear emergence. This means that social complexity is an inherent characteristic of all human societies, not just complex ones.

All human societies need energy and resources to sustain themselves. Beyond these so-called endosomatic needs, societies also have exosomatic needs, that is, energy requirements for material and technological maintenance and development. The social structures necessary for the exploitation of energy and resources can only emerge through the exchange and processing of information for communication, maintaining social connections, sharing knowledge, enabling innovation, and coordinating activities.

I assess social complexity through three main flows:

I define social complexity as the extent to which a social entity can exploit, process and consume flows of energy, resources and information (Daems, 02021). A society is not more complex because it is more civilized, but because it extracts more energy and resources from its environment or transmits information more efficiently. With this definition, complexity is dissociated from both social and environmental sustainability. Societies that manage to extract more energy and resources are not necessarily sustainable. Nor does enhanced information transmission always benefit society, as is so clearly illustrated in today’s struggles with misinformation.

This approach provides a clear answer to what social complexity is, but does not yet explain how it develops. Authors such as Joseph Tainter have posited social complexity as a problem-solving tool (Tainter, 01996). Societies are continuously faced with selection pressures – e.g. subsistence, cooperation, competition, production, demography, etc. – that act as input information for decision-making strategies driving societal development on two levels (Cioffi-Revilla, 02005):

Let us take the example of a society faced with a bad harvest. Such a society needs to assess the causes of this situation and define its strategies accordingly. Did the failed harvest stem from bad luck? Crop disease? The wrath of the gods?

Once the situation is assessed, a proper strategy needs to be devised. Do they try again and hope for the best? Experiment with new types of crops? Perform the necessary rituals to appease the wronged gods? Or perhaps they appoint officials to monitor agricultural production. Some strategies can be one-offs, such as a sacrifice or an official inspection. Or they can persist and become entrenched in the social fabric, such as when divine favor becomes indispensable for ensuring successful harvests, or a central government extends its control through a new bureaucratic system. Social structures do not spring forth fully-fledged from one day to the next, but are the result of incremental expansion, addition, and recombination of the outcomes of day-to-day decision-making processes.

As a system grows more complex, it self-organizes into nested groups that can take shape as horizontal networks or vertical hierarchies. When nested units across multiple scales become integrated within the same system, non-linear emergence and feedback loops across scales can generate some of the most powerful outcomes of complex system dynamics. A good example can be found in the process of energized crowding (Bettencourt, 02013; Smith, 02019). Drawn from the field of urban studies, energized crowding is what turns cities into “social reactors.” This is the idea that as more people live together in higher densities, more social interactions and exchange of information produces more social outcomes, both positive and negative. Bigger communities tend to proportionally display higher levels of innovation, income, and productivity, but also higher crime and scalar stress. All of the things drawing us towards the buzz of city life are ultimately born from the interactions between people.

Complexity formation is not without risk. Larger cities or polities tend to draw in population from a larger area. This requires a larger catchment, fulfilled through self-subsistence production, by importing goods, or both. As capital of the Roman empire, Rome grew to a population of over 1,000,000 people. Such a massive concentration of people was unthinkable without the structures of empire such as the ‘Annona’, state-sponsored grain subsidies relying on large-scale grain imports from Egypt, North Africa, and Sicily. Larger societies have a proportionally larger environmental footprint due to higher exosomatic needs. Rome needed not only food to sustain its population, but also resources to maintain its buildings, institutions, artisans, and cultural amenities. Moreover, as societies continue to implement changes over the long term, past measures could trigger future challenges which, in turn, need to be dealt with. Over time, a society builds an “ever denser scaffolding structure of related and interacting institutions” (van der Leeuw, 02016, p.168). The risks of this continued problem-solving process are twofold:

Societies generally tend to first use simple and cost-effective efforts with high returns on investment. As iterations continue, solutions to maintain societal structures become more complicated and costly, with diminishing proportionate marginal returns. Beyond some of the more spectacular causes of the fall of Rome proposed by Gibbon and others, such as large-scale invasions or civil strife, this slow “rigidification” is far less visible, but no less impactful. It is likely no coincidence that waves of administrative reorganizations followed in ever-quickening succession during the Late Roman period. Societies that do not have the expertise or flexibility to deal with new challenges could undergo a “tipping point” leading to drastic societal transformations generally associated with societal collapse. However, collapse only makes sense from a top-down perspective. During the Late Bronze Age (around 1200 BCE), a widespread disintegration of polities across the eastern Mediterranean and Near East occurred, including the Hittites of Anatolia (modern Turkey), Mycenaean Greece, the Egyptian New Kingdom, and the Middle Assyrian Empire (modern Iraq). Recent archaeological research, however, has found abundant evidence for local communities that continued to be inhabited and even thrive.

An explanation can be found in another property of complex systems called “near decomposability” (Simon, 01962). This refers to stronger connectivity between units of a similar type and the ability of units to operate semi-independently from others in the system. For example, households share stronger ties and interact more frequently with other households in the same community than with those of another community. Units that make up nested systems can often continue to function even when links to other units break down. If a larger polity, say the Hittite state, were to disintegrate, local or regional levels may have continued largely unaffected. Scalar divisions can therefore act as “fault lines” along which polities can be broken up, apparently collapsed when seen from a top-down perspective, but maintaining a bottom-up continuity.

Social complexity formation is a complicated process drawing on the exploitation, processing, and consumption of interrelated flows of energy, resources, and information. It is neither intrinsically good as was the belief of social evolutionists, nor does it inevitably lead to societal collapse. It is a phenomenon with both positive and negative consequences.

Earlier I outlined how direct parallels with biological evolution resulted in social evolutionism and a problematic conceptualization of teleological trajectories of social complexity. Nevertheless, evolution can offer fruitful metaphors to generate deeper insight into social complexity formation. The evolutionary taxonomic space is composed of a near-infinite number of dimensions, each corresponding to a particular characteristic of an organism (Hutchinson, 01978). Yet, organisms are part of nested clusters (species, genus, family, order, etc.) taking up specific portions of this space. This means that even though biological evolution has been at work for millions of years, only a very limited area of the potential space has been actualized (Lewontin, 02019). Exploring the full potential taxonomic space would take millions upon millions of years.

Human societies likewise are clustered within the taxonomic space of all possible societal configurations. Current states are built from past configurations, in combination with the contingent opening of new pathways of development. At its current pace, humankind will not have sufficient time to explore the potential configuration space of societal organizations that will allow us to balance increasing social complexity with a sustainable dynamic within our natural environment. Yet, this should not discourage us from using the necessary long-term perspective to look beyond the edges of the current, toward what might be possible in the future. One thing is clear: Any foray into the future would do well to also have an eye on the past.

Auban, J., Martin, A. and Barton, C., 02013. Complex Systems, Social Networks, and the evolution of Social Complexity in the East of Spain from the Neolithic to Pre-Roman Times. In: M. Berrocal, L. Sanjuán and A. Gilman, eds. The Prehistory of Iberia: Debating Early Social Stratification and the State. New York: Routledge.

Bettencourt, L., 02013. The Origins of Scaling in Cities. Science, 340(6139), pp.1438–1441. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235823

Cioffi-Revilla, C., 02005. A Canonical Theory of Origins and Development of Social Complexity. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 29(2), pp.133–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222500590920860

Daems, D., 02021. Social Complexity and Complex Systems in Archaeology. London: Routledge.

Hutchinson, G.E., 01978. An Introduction to Population Ecology. New Haven: Yale University Press.

van der Leeuw, S., 02016. Uncertainties. In: M. Brouwer Burg, H. Peeters and W.A. Lovis, eds. Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis in Archaeological Computational Modeling, Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. [online] Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp.157–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27833-9_9

Lewontin, R., 02019. Four Complications in Understanding the Evolutionary Process. In: D.C. Krakauer, ed. Worlds Hidden in Plain Sight. SFI Press. pp.97–113.

Morris, I., 02013. The Measure of Civilization: How Social Development Decides the Fate of Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Service, E.R., 01962. Primitive social organization: an evolutionary perspective. New York: Random House.

Simon, H.A., 01962. The Architecture of Complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 106(6), pp.467–482.

Smith, M., 02019. Energized Crowding and the Generative Role of Settlement Aggregation and Urbanization. In: A. Gyucha, ed. Coming Together: Comparative Approaches to Population Aggregation and Early Urbanization. New York: State University of New York Press. pp.37–58.

Tainter, J., 01996. Complexity, Problem Solving and Sustainable Societies. In: R. Costanza, O. Segura and J. Martinez-Alier, eds. Getting Down To Earth: Practical Applications of Ecological Economics. Washington DC: Island Press. pp.61–76.

Here was a house that had wind chimes and bird feeders and monk parakeets mobbing the trees.

For the past year or so, as I’ve been riding around on my bike, I’ve been wondering what it does to your psyche to see little old houses disappear every week. Even though I know in my cortex what’s going on — the real estate market, tech money, post-pandemic coastal fleeing, etc. — it’s still deeply unsettling.

There is no shortage of pieces about how much Austin has changed, but I’d been waiting for a piece of writing to help me understand the feeling I was getting from it all. This feeling, not of bewildering change, but creeping… dread? Disappearance? Loss?

I found it, unexpectedly, today in Jon Mooallem’s piece about the pandemic, sociology, and dipping into a Covid oral-history project, “What Happened To Us.”

I was particularly drawn to this bit, “What is normal life?”

In 1903, the German sociologist Georg Simmel took a long, hard look at life in big cities and concluded — I’m paraphrasing — that normal life is basically a continuous bombardment of irreconcilable psychic noise. “Man is a creature whose existence is dependent on differences,” Simmel explained in an essay called “The Metropolis and Mental Life.” We enter each moment expecting that it will resemble the last one, and if we find that continuity between past and present disrupted, it pays to perk up. This was true in rural life at least, Simmel argued, where certain natural rhythms blanketed people in a “steady equilibrium of unbroken customs.” But a city never stops throwing new stimuli at us, engaging our impulse to notice and differentiate. In a city, there’s simply too much newness for a human being to perceive without breaking. The psyche therefore “creates a protective organ for itself against the profound disruption,” Simmel wrote — a dispassionate crust he called “the blasé attitude.” The blasé attitude, he wrote, is “an indifference toward the distinctions between things. … The meaning and the value of the distinctions between things, and therewith of the things themselves, are experienced as meaningless.” So, extrapolating from Simmel: One way to describe normal life would be as an arrangement of circumstances that can be successfully ignored.

The other bit that spoke to me was Émile Durkheim’s concept of “anomie.”

Durkheim introduced his concept of anomie most fully in an 1897 book-length study, “Suicide.” Suicides, Durkheim contended, “express the mood of societies,” and he was keen to figure out why their rates increased not just during economic depressions but also during times of rapid economic growth and prosperity. He concluded that any dramatic swing within society, regardless of direction, leaves people unmoored, plunging them into a condition of “anomie.” Swidler told me that, while the word is often translated as “alienation,” it may more accurately be understood as “normlessness.” “He means that the underlying rules are just not clear,” she said. Anomie sets in when a society’s values, routines and customs are losing their validity but new norms have not yet solidified. “The scale is upset,” Durkheim wrote, “but a new scale cannot be immediately improvised. …The limits are unknown between the possible and the impossible.”

Anomie, Durkheim said, “begets a state of exasperation and irritated weariness.”

It’s not just all the teardowns — it’s the ice storms, the power outages, the literal shifting clay of the soil. You’re constantly being made aware, day after day, of how unstable everything is.

I think of a city as a big collage in several dimensions, which is one of the reasons I like to live in one. There’s always something new around, something to look at, something to spark my imagination. It’s good for what Rimbaud called the “derangement of the senses.”

But there are times when it goes too far and other times when one wants to cease being an artist and just feel like a normal human. Some of the ways I’ve made living in the city tolerable from a perspective of peace: observe the seasons (yes, we have seasons here, you just have to pay attention), help Meg in the garden, bike around with my friends, watch the owls, establish dumb rituals with the kids, etc. The sociologists in the piece call these strategies, meant to bring about some kind of normalcy, “repertoires of repair.”

I like that term and will continue to look for more practices to add to my repertoire.