Every person starts as just one fertilized egg. By adulthood, that single cell has turned into roughly 37 trillion cells, many of which keep dividing to create the same amount of fresh human cells every few months.

But those cells have a formidable challenge. The average dividing cell must copy—perfectly—3.2 billion base pairs of DNA, about once every 24 hours. The cell’s replication machinery does an amazing job of this, copying genetic material at a lickety-split pace of some 50 base pairs per second.

Still, that’s much too slow to duplicate the entirety of the human genome. If the cell’s copying machinery started at the tip of each of the 46 chromosomes at the same time, it would finish the longest chromosome—No. 1, at 249 million base pairs—in about two months.

“The way cells get around this, of course, is that they start replication in multiple spots,” says James Berger, a structural biologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, who co-authored an article on DNA replication in eukaryotes in the 2021 Annual Review of Biochemistry. Yeast cells have hundreds of potential replication origins, as they’re called, and animals like mice and people have tens of thousands of them, sprinkled throughout their genomes.

“But that poses its own challenge,” says Berger, “which is, how do you know where to start, and how do you time everything?” Without precision control, some DNA might get copied twice, causing cellular pandemonium.

Keeping tight reins on the kickoff of DNA replication is particularly important to avoid that pandemonium. Today, researchers are making steps toward a full understanding of the molecular checks and balances that have evolved in order to ensure that each origin initiates DNA copying once and only once, to produce precisely one complete new genome.

Bad things can happen if replication doesn’t start correctly. For DNA to be copied, the DNA double helix must open up, and the resulting single strands—each of which serves as a template for building a new, second strand—are vulnerable to breakage. Or the process can get stuck. “You really want to resolve replication quickly,” says John Diffley, a biochemist at the Francis Crick Institute in London. Problems during DNA replication can cause the genome to become disorganized, which is often a key step on the route to cancer.

Some genetic diseases, too, result from problems with DNA replication. For example, Meier-Gorlin syndrome, which involves short stature, small ears, and small or no kneecaps, is caused by mutations in several genes that help to kick off the DNA replication process.

It takes a tightly coordinated dance involving dozens of proteins for the DNA-copying machinery to start replication at the right point in the cell’s life cycle. Researchers have a pretty good idea of which proteins do what, because they’ve managed to make DNA replication happen in cell-free biological mixtures in the lab. They’ve mimicked the first crucial steps in initiation of replication using proteins from yeast—the same kind used to make bread and beer—and they’ve mimicked much of the entire replication process using human versions of replication proteins, too.

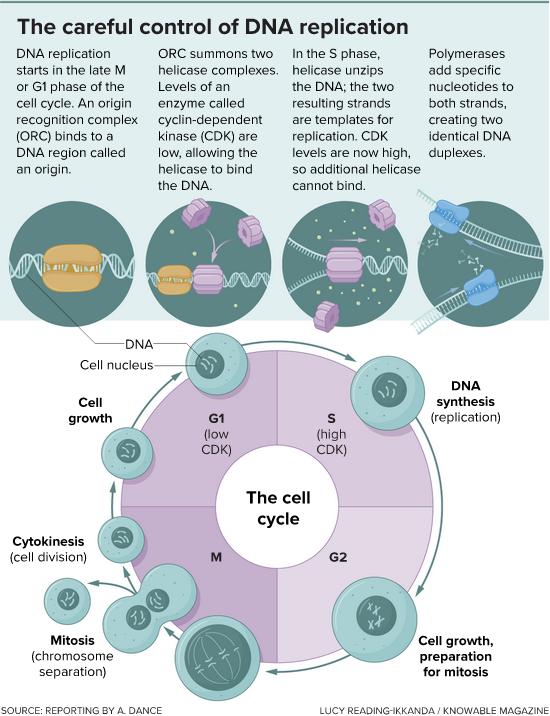

The cell controls the start of DNA replication in a two-step process. The whole goal of the process is to control the actions of a crucial enzyme—called a helicase—that unwinds the DNA double helix in preparation for copying it. In the first step, inactive helicases are loaded onto the DNA at the origins, where replication starts. During the second step, the helicases are activated, to unwind the DNA.

Kicking off the process is a cluster of six proteins that sit down at the origins. Called ORC, this cluster is shaped like a double-layer ring with a handy notch that allows it to slide onto the DNA strands, Berger’s team has found.

In baker’s yeast, which is a favorite for scientists studying DNA replication, these start sites are easy to spot: They have a specific, 11- to 17-letter core DNA sequence, rich in adenine and thymine chemical bases. Scientists have watched as ORC grabs onto the DNA and then slides along, scanning for the origin sequence until it finds the right spot.

But in humans and other complex life forms, the start sites aren’t so clearly demarcated, and it’s not quite clear what makes the ORC settle down and grab on, says Alessandro Costa, a structural biologist at the Crick Institute who, with Diffley, wrote about DNA replication initiation in the 2022 Annual Review of Biochemistry. Replication seems more likely to start in places where the genome—normally tightly spooled around proteins called histones—has loosened up.

The initiation of DNA replication starts at the tail end of the previous cell division and continues through the cell cycle phase known as G1. DNA synthesis happens during the S phase. Levels of a protein called CDK are critical to ensuring that DNA is replicated once and only once. When CDK levels are low, helicases can jump onto the DNA and start to unwind it. But repeat binding does not happen because CDK levels rise, and this blocks the helicase from binding again. (credit: Knowable Magazine)

Once ORC has settled onto the DNA, it attracts a second protein complex: one that includes the helicase that will eventually unwind the DNA. Costa and colleagues used electron microscopy to work out how ORC lures in first one helicase, and then another. The helicases are also ring-shaped, and each one opens up to wrap around the double-stranded DNA. Then the two helicases close up again, facing toward each other on the DNA strands, like two beads on a string.

At first, they just sit there, like cars with no gas in the tank. They haven’t been activated yet, and for now the cell goes about its usual business.

Things kick into high gear when a crucial molecule called CDK waves the green flag, jump-starting chemical steps that lure in even more proteins. One of them is DNA polymerase—what Costa calls the “typewriter” that will build new DNA strands—which hitches onto each helicase. Others activate the helicases, which can now burn energy to chug along the DNA.

As this occurs, the helicases change shape, pushing on one DNA strand and pulling on the other. This creates strain on the weak hydrogen bonds that normally hold the two strands together by the bases—the As, Cs, Ts and Gs that make up the rungs of the DNA ladder. The two strands get ripped apart. Costa and colleagues have observed how the two helicases untwist the DNA between them, and they’ve seen how the helicases keep the unbound bases stable and out of the way.

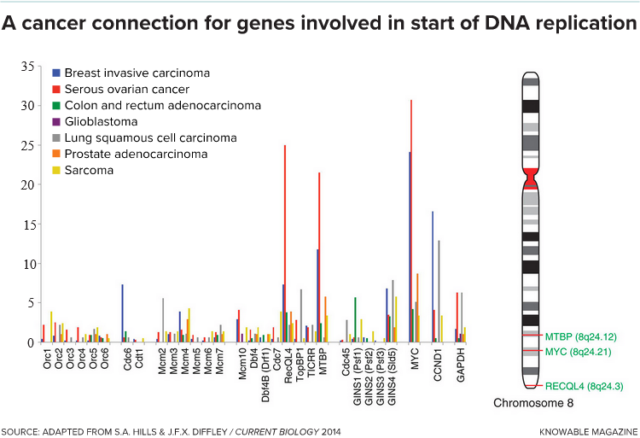

Left: Several genes involved in the initiation of DNA replication (horizontal axis) are amplified—that is, mistakenly copied in extra numbers — to varying degrees (vertical axis) in different cancers. Right: On chromosome 8, a cluster of three genes—shown in green text—are frequently amplified together in certain cancers. (credit: Knowable Magazine)

At first, both helicases are wrapped around both strands of DNA, and they can’t get very far like this, because they are facing each other and will just run into each other. But next, they each undergo a change in position, spitting one DNA strand or the other out of the ring. Now separated, they can jostle past each other, and replication proceeds apace.

Each helicase motors along its single strand, in the opposite direction from the other. They leave the origin behind and yank apart those hydrogen-bonded base pairs as they travel. The DNA polymerase is right behind, copying the DNA letters as they’re freed from their partners.

CDK’s second job is to stop any more helicases from hopping on the origins. Thus, there is one start of replication per origin, ensuring proper copying of the genome—although copying doesn’t begin at the same time at each site. The whole process of DNA replication, in human cells, takes about eight hours.

There is still plenty to be worked out. For one thing, the DNA that’s being copied is not a naked double helix. It’s wrapped around histones and attached to lots of other proteins that are busy turning genes on or off or making RNA copies of the genes. How do those jostling proteins affect each other and avoid getting in each other’s way?

Beyond this fascinating, fundamental biology—a remarkable process essential for all life on Earth—there are implications for diseases like cancer. Scientists already know that faulty replication can destabilize DNA, and an unstable genome that’s prone to mutation may be an early hallmark of cancer development. And they are further investigating links between replication proteins and cancer.

“I think that there are opportunities for therapeutic interventions for these systems,” says Berger, “once we have enough insights about how they work and what they look like.”

Amber Dance, a science writer in the Los Angeles area, also likes to break large tasks into smaller segments: It took her five days to complete the steps to draft this article. This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.

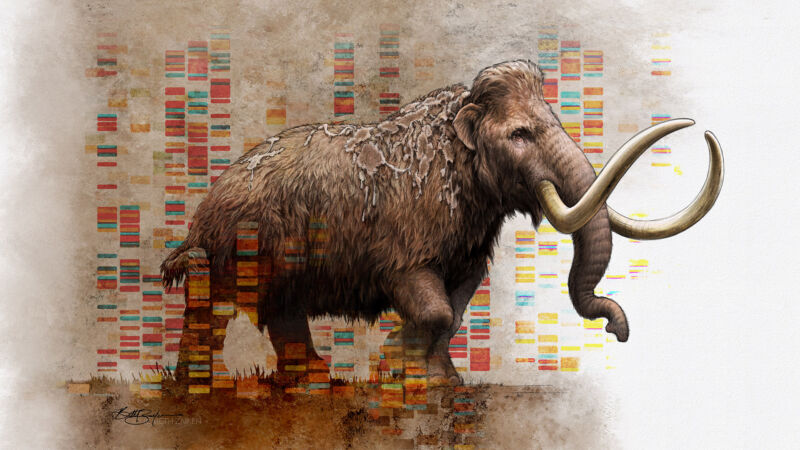

Enlarge (credit: Beth Zaiken)

An international team of scientists has published the results of their research into 23 woolly mammoth genomes in Current Biology. As of today, we have even more tantalizing insights into their evolution, including indications that, while the woolly mammoth was already predisposed to life in a cold environment, it continued to make further adaptations throughout its existence.

Years of research, as well as multiple woolly mammoth specimens, enabled the team to build a better picture of how this species adapted to the cold tundra it called home. Perhaps most significantly, they included a genome they had previously sequenced from a woolly mammoth that lived 700,000 years ago, around the time its species initially branched off from other types of mammoth. Ultimately, the team compared that to a remarkable 51 genomes—16 of which are new woolly mammoth genomes: the aforementioned genome from Chukochya, 22 woolly mammoth genomes from the Late Quaternary, one genome of an American mastodon (a relative of mammoths), and 28 genomes from extant Asian and African elephants.

From that dataset, they were able to find more than 3,000 genes specific to the woolly mammoth. And from there, they focused on genes where all the woolly mammoths carried sequences that altered the protein compared to the version found in their relatives. In other words, genes where changes appear to have been naturally selected.

It’s possible to retrieve forensically relevant information from human DNA in household dust, a new study finds.

After sampling indoor dust from 13 households, researchers were able to detect DNA from household residents over 90% of the time, and DNA from non-occupants 50% of the time. The work could be a way to help investigators find leads in difficult cases.

Specifically, the researchers were able to obtain single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, from the dust samples. SNPs are sites within the genome that vary between individuals—corresponding to characteristics like eye color—that can give investigators a “snapshot” of the person.

“SNPs are just single sites in the genome that can provide forensically useful information on identity, ancestry, and physical characteristics—it’s the same information used by places like Ancestry.com—that can be done with tests that are widely available,” says Kelly Meiklejohn, assistant professor of forensic science and coordinator of the forensic sciences cluster at North Carolina State University and corresponding author of the study in the Journal of Forensic Sciences.

“Because they’re single sites, they’re easier to recover for highly degraded samples where we may only be able to amplify short regions of the DNA,” Meiklejohn says.

“Traditional DNA analysis in forensics amplifies regions ranging from 100 to 500 base pairs, so for a highly degraded sample the large regions often drop out. SNPs as a whole don’t provide the same level of discrimination as traditional forensic DNA testing, but they could be a starting place in cases without leads.”

Meiklejohn and her team recruited 13 diverse households and took cheek swabs from each occupant along with dust samples from five areas within each home: the top of the refrigerator, inside the bedroom closet, the top frame of the front door, a bookshelf or photo frame in the living room, and a windowsill in the living room.

Utilizing massively parallel sequencing, or MPS, the team was able to quickly sequence multiple samples and target the SNPs of interest. They found that 93% of known household occupants were detected in at least one dust sample from each household. They also saw DNA from non-occupants in over half of the samples collected from each site.

“This data wouldn’t be used like traditional forensic DNA evidence—to link a single individual to a crime—but it could be useful for establishing clues about the ancestry and physical characteristics of individuals at a scene and possibly give investigators leads in cases where there may not be much to go on,” Meiklejohn says.

“But while we know it is possible to detect occupants versus non-occupants, we don’t know how long an individual has to stay in a household before they leave DNA traces in household dust.”

The researchers plan to address the question of how much time it takes for non-occupants to be detected in dust in future studies. Meiklejohn sees the work as being useful in numerous potential investigative scenarios.

“When perpetrators clean crime scenes, dust isn’t something they usually think of,” Meiklejohn says. “This study is our first step into this realm. We could see this being applied to scenarios such as trying to confirm individuals who might have been in a space but left no trace blood, saliva, or hair. Also for cases with no leads, no hit on the national DNA database, could household dust provide leads?”

The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine funded the work. Additional coauthors are from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NC State.

Source: NC State

The post Household dust harbors forensic DNA info appeared first on Futurity.

New research digs into when and how horses spread and flourished in the western US.

Until now, the accepted theory of horses arriving to the Great Plains and Northern Rockies was shaped by word of mouth and lore.

The new research, published in Science, establishes the expansion of the domesticated horse through DNA evidence.

The researchers compared genetic samples from horse remains at archeological sites to the genetics of rare, early horse breeds similar to those that came over with early settlers. They found familial ties indicating that horses arrived with Europeans and then made their way west during the 17th century. Horses were not out west 10,000 years ago when nomadic people first arrived in North America.

Some archaeological evidence like bones, horseshoes, and colonial items have been found in various locations across the US and occasionally in deposits west of the Mississippi. However, when it came to whether horses were always in the western US or if they came over with Europeans and Spaniards and made it from the East Coast to the Rockies, horses left an open book.

Horses themselves and horsemanship seemed to have spread west faster than Europeans did, the researchers also found. Some of the early horse fossils showed horses were established in the Great Plains before the European and Spanish made their way west. More research needs to be done to understand just how this happened, but it’s another fascinating finding.

Besides filling in some blanks in the history books, this research has real implications for how horses are selected for breeding today.

“We can see aspects of genetic selection from 3,000 years ago that are likely important for a good temperament and a strong back in our horses today,” says Samantha Brooks, associate professor of equine genetics at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) whose lab collected DNA samples for the study and helped analyze the data.

“Those are things horse people still struggle with today. The more we learn about genetics that control those aspects of horse health, the better off we can take care of our horses today.”

The new findings shed light on the role horses played in Indigenous cultures. Horses have been a significant part of many Native American cultures, but this research clarifies when and how horses were integrated into their lives.

“European nations valued the horse, but horses did not become a life changing cultural icon to them as it did to the Indigenous people,” Brooks. “The horse suited the nomadic plains lifestyle so remarkably well.”

Nomadic people may not have made it to North America 10,000 years ago with horses in hand, but somehow their way of life was so well suited to the horse that once it arrived in the western US plains, it thrived as part of the Native American culture.

“Some tribal historians thought it was possible that the horses found out west were genetically distinct from the lineage that arrived with Spanish and European colonizers, but the data showed that is unlikely,” says Brooks.

“This is almost a more remarkable finding. The level of skill the Native peoples have with horse handling and management is truly impressive, and this study tells us that they developed that skill in a relatively short amount of time.”

One of the fossilized horses used in the study was found to have sustained a skull fracture at some point in its life that was unrelated to its later death. An injury like that would have almost certainly required supportive care in order to survive, a testament to how tough these early horses had to be, and to how well Indigenous communities cared for the animals.

“Native people adapted and flourished as a horse culture in the blink of a historical eye,” says Brooks.

The researchers thank the Livestock Conservancy and owners and breeders of rare horse breeds such as the Galiceño, Marsh Tacky, and Florida Cracker Horse that contributed genetic samples to the study. Without those samples, this research would not have been possible.

Source: University of Florida

The post When did horses get to the western US? appeared first on Futurity.

A new forensic science study sheds light on how the bones of infants and children decay.

The findings will help forensic scientists determine how long a young person’s remains were at a particular location, as well as which bones are best suited for collecting DNA and other tissue samples that can help identify the deceased.

“Crimes against children are truly awful, and all too common,” says Ann Ross, a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University and coauthor of the study in the journal Biology.

“It is important to be able to identify their remains and, when possible, understand what happened to them. However, there is not much research on how the bones of infants and children break down over time. Our work here is a significant contribution that will help the medical legal community bring some closure to these young people and, hopefully, a measure of justice.”

For the study, the researchers used the remains of domestic pigs, which are widely used as an analogue for human remains in forensic research. Specifically, the researchers used the remains of 31 pigs, ranging in size from 1.8 kilograms (4 pounds) to 22.7 kilograms (50 pounds). The smaller remains served as surrogates for infant humans, up to one year old. The larger remains served as surrogates for children between the ages of one and nine.

The surrogate infants were left at an outdoor research site in one of three conditions: placed in a plastic bag, wrapped in a blanket, or fully exposed to the elements. Surrogate juveniles were either left exposed or buried in a shallow grave.

The researchers assessed the remains daily for two years to record decomposition rate and progression. The researchers also collected environmental data, such as temperature and soil moisture, daily.

Following the two years of exposure, the researchers brought the skeletal remains back to the lab. The researchers cut a cross section of bone from each set of remains and conducted a detailed inspection to determine how the structure of the bones had changed at the microscopic level.

The researchers found that all of the bones had degraded, but the degree of the degradation varied depending on the way that the remains were deposited. For example, surrogate infant remains wrapped in plastic degraded at a different rate from surrogate infant remains that were left exposed to the elements. The most significant degradation occurred in juvenile remains that had been buried.

“This is because the bulk of the degradation in the bones that were aboveground was caused by the tissue being broken down by microbes that were already in the body,” says corresponding author and PhD candidate Amanda Hale. “Buried remains were degraded by both internal microbes and by microbes in the soil.”

Hale is a research scientist at SNA International working for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

The researchers also used statistical tools that allowed them to better assess the degree of bone degradation that took place at various points in time.

“In practical terms, this is one more tool in our toolbox,” Ross says. “Given available data on temperature, weather, and other environmental factors where the remains were found, we can use the condition of the skeletal remains to develop a rough estimate of when the remains were deposited at the site. And all of this is informed by how the remains were found. For example, whether the remains were buried, wrapped in a plastic tarp, and so on.

“Any circumstance where forensic scientists are asked to work with unidentified juvenile remains is a tragic one. Our hope is that this work will help us better understand what happened to these young people.”

Source: NC State

The post Forensics study clarifies how bones of children decay appeared first on Futurity.

I wrote the first sentences that appear in Wolfish almost ten years ago, during the summer of 2013. I was about to be a senior in college, and I was doing my best to blink away the pending maw of where-to-go, of what-comes-next.

I had left my family in Oregon to attend a college in Maine. It was there that I learned who Joan Didion was, and about how it had taken her living in New York City to turn her gaze back home. “I sat on one of my apartment’s two chairs . . . and wrote myself a California river,” Didion later said about Run River. Her words seemed like a decent writing prompt: to write about the place I had left, a place I was not sure I would ever live again. I remember sitting beneath the peeling wallpaper of my summer sublet, listening to the rumble of the tenant below, a man who, we later learned, was breeding pythons. Oregon, I wrote at the top of a new document. A place, like so many others, where white settlers had killed all the wolves. A place, as I was researching for my Environmental Studies thesis, where wolves were coming back.

“Visit someplace you have ‘roots’ and it is easy to encounter the landscape as a strata of story,” I write in Wolfish. Beneath the crust of one’s lived, sensory experience sits the fossilized lore of family arrival. The thickest part, that bedrock of environmental and social history, underlies everything but is too rarely glimpsed. The best writers on this subject dirty their fingernails as they move between the layers. I am interested in place because I am provoked by the experience of being a body in the current of time. What does it mean to be me, here, now? One node in an ecosystem of not only species but stories, mythologies of belonging and fear and love. My favorite writing about place moves kaleidoscopically between art and science, past and present, humans and non-humans, internal and external lives. The author’s relationship with place is not always the explicit subject of the following books—nor is it in Wolfish—but it’s a thread that runs through the pages. A stitch that sews both self and world into being.

***

Wave, Sonali Deraniyagala

Deraniyagala’s memoir is one of the most haunting books I’ve ever read, about the author’s unfathomable grief of surviving Sri Lanka’s 2004 tsunami while losing her husband, children and parents. I’ve returned again and again to the book for how lyrically Deraniyagala writes emotion into landscape, calling attention to the ways we project ourselves into the natural world, and vice versa. “I spurn its paltry picture-postcardness,” she writes at one point about Sri Lanka, where she was born. “Those beaches and bays are too pretty and tame to stand up to my pain, to hold it, even a little.” How to write about an ocean full of beauty, which has taken so much beauty from you? It is both “our killer” and a place of sunset calm, a sea coated in “crushed crimson glass.”

The Second Body, by Daisy Hildyard

In this book-length essay, Hildyard posits that we have two bodies: one contained by skin, the other the sprawl of one’s biological life as it overlaps with other species. “Your body is not inviolable,” she writes. “Your body is infecting the world—you leak.” She strives to understand this ‘second body’ by probing how humans define and interact with animal life, interviewing both a Yorkshire butcher and a criminologist who speaks to silver foxes kept as pets. This book put language to feelings I’d sensed but never been able to articulate, redefining the ways I think about intersections of human and non-human lives.

Small Bodies of Water, by Nina Mingya Powles

Powles’ mother was born in Borneo, where the author learned to swim, but Powles herself was born in New Zealand, and grew up partially in China, then moved to London. Moving between modes of memoir, art criticism, and nature writing, Small Bodies of Water is like swimming through a dream populated with the crystalline detail of both “the Atlas moth with white eyes on its wings” and a viral Twitter clip of “flame being whipped into spirals by the wind.” She writes beautifully about migration and belonging and girlhood, and as a writer, I felt particularly attuned to how carefully she pins her world to the page: “Our language for colours shifts according to our own experiences and memories: the blue of a giant Borneo butterfly’s wings pinned in a glass case; the yellow at the centre of a custard tart.”

Cold Pastoral, by Rebecca Dunham

Weaving elegy, lyric, documentary, and investigation, this poetry collection holds at its center the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, confronting the question of how to witness a world that is both natural and unnatural, simultaneously mangled and tended by our touch. After the explosion, workers jump off the rig into a “sea stirred to wildfire,” while miles away, in her own yard, “lilies / startle [the] garden pink / and gold.”

Bright Unbearable Reality, by Anna Badkhen

I bought this book on the perfection of its cover alone, then swiftly fell for the roaming logic of Badkhen’s essays, which unspool themes of communion and human migration, often while the author herself is on the road, in Ethiopia or Oklahoma or Chihuahua City. “The travel I witness often happens under duress,” she writes. “I have spent my life documenting the world’s iniquities, and my own panopticon of brokenness comprises genocide and mass starvation, loved ones I have lost to war, friends’ children who died of preventable diseases.” So much heartache in these pages, but I was persistently buoyed by the tenderness she brings to the world and its inhabitants. Even a pronghorn on the horizon, Badkhen tells us, is related to a giraffe.

In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, by Etel Adnan

Made up of lyrical vignettes, this genre-crossing memoir is testament to Adnan’s transcultural and nomadic self, as the text moves between Lebanon, France, Greece, Syria, and the U.S. Her translingual research and progressive activism underlie her observations about self and world. “I reside in cafes: they are my real homes,” she writes. “In Beirut my favorite one has been destroyed. In Paris, Café de Flore is regularly invaded by tourists.” I’m perhaps most compelled by how she writes about rootlessness: “feeling at ease, or rather identifying with drafts of air, dispersing dry leaves and balloons, taking taxis just because they were staring at me.”

Groundglass: An Essay, by Kathryn Savage

Full disclosure: because I overlapped with Savage in my MFA program, I’ve been admiring this hybrid project and her lyrical research process for years, but this book would have jumped off the shelf at me regardless. “Could there be something humbling and revolutionary in understanding myself as a site of contamination?” writes Savage. It’s a book about illness and grief and motherhood and U.S. Superfund sites (they appear like “confetti flecks” on the map), but also, implicitly, about the act of trying to understand pollution while, “Upstairs, Henry laughs, playing video games.” The book made me think not only of the porousness between earth and self, but between elegy and ode.

White Magic, by Elissa Washuta

“When I felt myself shredded, I used to wade into Lake Washington…The land put me back together,” writes Washuta, a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe indigenous to the region. She now lives in Ohio, where “the land and I talk like strangers,” and tensions around place animate this hypnotic memoir. “I love living in Ohio, I love my forever house, but my missing of Seattle feels almost violent inside of me sometimes, and that is probably the real heartbreak the book is about,” Washuta said in an interview. Moving from the colonial history of Columbia River land treaties to Twin Peaks and the Oregon Trail II video game, Washuta makes visible that which is too often unseen: the modes by which place is created, inherited, metabolized.

River, by Esther Kinsky

Translated from German by Iain Galbraith, Kinsky’s novel constellates the life of a woman who, for unknown reasons, moves outside London near the River Lea (“small…populated by swans”), reminiscing about other rivers from her past while she goes for long solitary walks. The novel moves essayistically, which is to say, like a river, “constantly brushing with the city and with the tales told along its banks,” ebbing with ecological observation and memory.

Borealis, by Aisha Sabatini Sloan

An expansive collage encompassing soundtracks, flashbacks to past lovers, conceptual art, and snippets from nature documentaries and overheard dialogues, Borealis is a constellation of observations about queer relationships, blackness, and Sabatini Sloan’s life in a small Alaskan town. The animating pulse of the book could be the quote Sabatini Sloan includes by Renee Gladman: “You had to think about where you were in a defined space and what your purpose was for being there.”

Of course, you’ll also want to scoop up a copy of Erica Berry’s Wolfish—preorders are like gifts to your future self <3

— The Eds.

“This is one of those stories that begins with a female body. Hers was crumpled, roadside, in the ash-colored slush between asphalt and snowbank.”

So begins Erica Berry’s kaleidoscopic exploration of wolves, both real and symbolic. At the center of this lyrical inquiry is the legendary OR-7, who roams away from his familial pack in northeastern Oregon. While charting OR-7’s record-breaking journey out of the Wallowa Mountains, Erica simultaneously details her own coming-of-age as she moves away from home and wrestles with inherited beliefs about fear, danger, femininity, and the body.

As Erica chronicles her own migration—from crying wolf as a child on her grandfather’s sheep farm to accidentally eating mandrake in Sicily—she searches for new expressions for how to be a brave woman, human, and animal in our warming world. What do stories so long told about wolves tell us about our relationship to fear? How can our society peel back the layers of what scares us? By strategically unspooling the strands of our cultural constructions of predator and prey, and what it means to navigate a world in which we can be both, Erica bridges the gap between human fear and grief through the lens of a wrongfully misunderstood species.

***

“DNA is the gift that keeps on giving, whether you’re ready or not,” writes Dorothy Ellen Palmer. Palmer and her half-brother, Don Doiron, were born a week apart in 1955, in the same hospital, to different mothers: Florence McLean and Ana Cifuentes. It took 62 years before they learned that they were half-siblings, and were adopted into very different families. Palmer pens a poignant personal essay about searching for the truth, their buried family history in a time when “silence ruled” and “adoption was never discussed,” and their birth father. It’s a moving story about finding one’s place in the world.

Even as adults, adoptees have long been treated like children who need to be protected from our own truths. When we came of age in the 1970s, Don and I had to apply for the scant details, called non-identifying information, the government then permitted us to know. We received sparse biographies of our birth mothers (age, birthplace, education and occupation) and next to nothing about our birth fathers. It wasn’t enough for either of us.

Today, Don and I are still piecing together our stories. Not everything we’ve learned has been happy. Some of our shared history is heart-rending. But we claim every bit of our lives as our truth, as the story we have every right to know, to celebrate and to mourn, to pass on to our children.