In the last of this series of posts about this year's Annual Meeting, SSP's Marketing and Communications Committee asked members of our community what the conference meant to them.

The post Ask the Community: What Did SSP 2023 Mean to You? appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

The ORCID US consortium, managed by Lyrasis, is five years old in 2023 - hear about their progress so far and plans for the future in Alice Meadows' interview with their PID Program Leader, Sheila Raybun

The post The ORCID US Consortium at Five: What’s Worked, What Hasn’t, and Why? appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

The Philosophy Journal Insight Project (PJIP) “aims to provide philosophy researchers with practical insights on potential venues for publication.”

Its main offering is a spreadsheet that provides information about journals’ subject matter, word limits, type of peer review, open access status, rankings, impact information, acceptance rates, review times, reviewing quality, and so on.

Put together by Sam Andrews, a philosophy PhD student at the University of Birmingham, the site, which he says is a work in progress, currently has information about 47 journals.

You can check it out here.

The post New Site Collects and Standardizes Philosophy Journal Information first appeared on Daily Nous.

The Directory of Open Access Books (DOAB) is celebrating its 10-year anniversary, a great opportunity to reflect on how far we have come with open infrastructures for the distribution and discoverability of open access books (monographs, edited collections, and other long-form publications).

The post Guest Post — Towards Global Equity for Open Access Books appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

I sure miss the days of supporting the H5P Kitchen project — if anything really hits the elements of the olde 5 Rs, to me, it’s the portability, platform independence, downloadability, reusability of H5P plus, the thing fe really love, built in metadata.

So when I spotted a reshare of this University Affairs online article on ChatGPT? We need to talk about LLMs my interest was in the writing — and it is a worthy read about getting beyond the AI inevitability to how we grapple with the murk of ethics.

But here is what jumped out to me in the middle of the article– OMG it’s H5P! I can from a kilometer away that’s what it is, an Interactive Hotspot Diagram.

Typical of H5P, this has a Reuse button (so you could download the .h5p source), an Embed code button (I could have inserted it here in my blog), but ones is missing… The one labeled “rights” which is actually the item’s metadata. You see, there is nothing that identifies the author of this content or how it is licensed — well until I squinted, in the image itself is © REBECCA SWEETMAN 2023. So what we have here are a fraction of the 5Rs.

Metadata, metadata, rarely loved or appreciated beyond librarians, archivists, data nerds. In the H5P Kitchen I wrote a guide to why/how this is used:

But I was curious about that LLM Hotspot, and it was 15 seconds of a web search on the title and adding “H5P” that got me to a source, of course, in the eCampusOntario H5P Studio— where we at least see the author credit, but alas, it was shared without specifying a license. Oh, I could have gotten there faster if I inspected the embed code the source is in the URL.

This is minor quibbling of course. I was tickled to see an interactive document in a web article. It’s just so close to making the best use of tools, but as the word “virtual” goes, it’s always “almost there”.

Featured Image:

"Researchers have only so many hours in a day; if they can spend one less hour on a research article because we have implemented improved workflows and better technology, that’s one more hour they can spend on research to try to save my life, and the lives of all ALS patients." In today's post, Bruce Rosenblum shares his experience as a clinical trial participant and how that contributed to scholarly publications.

The post Guest Post — Being Research Data appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Download the transcript of this interview.

For this episode of Platypod, I talked to Dr. Tanja Ahlin about her research, work, and academic trajectory. She’s currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, and her work focuses on intersections of medical anthropology, social robots, and artificial intelligence. I told her of my perspective as a grad student, making plans and deciding what routes to take to be successful in my field. Dr. Ahlin was very generous in sharing her stories and experiences, which I’m sure are helpful to other grad students as well. Enjoy this episode, and contact us if you have questions, thoughts, or suggestions for other episodes.

Dr. Tanja Ahlin, image from her personal website.

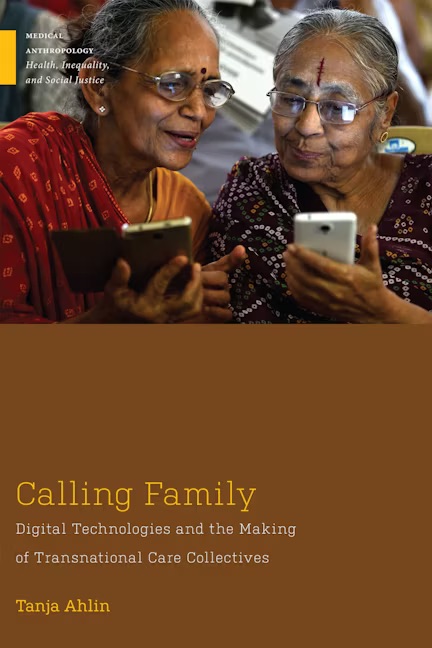

Dr. Tanja Ahlin is a medical anthropologist and STS scholar with a background in translation. She has translated books about technology and more. She has a master’s degree in medical anthropology, focusing on the topic of health and society in South Asia. Dr. Ahlin has been interested in e-health/telehealth for a long time, before the recent COVID-19 pandemic years, in which those words became part of our daily vocabulary. Her Ph.D., which she concluded at the University of Amsterdam, has focused on everyday digital technologies in elder care at a distance. Her Ph.D. research is being published as a book at Rutgers University Press. The book will be available for purchase starting on August 11, 2023.

Calling Family – Digital Technologies and the Making of Transnational Care Collectives | Rutgers University Press

In our conversation, we talked about Dr. Ahlin’s blog focusing on the Anthropology of Data and AI. This project—in which Dr. Ahlin writes about the intersection of tech and different fields such as robotics, policy, ethics, health, and ethnography—is a kind of translation work, since Dr. Ahlin is writing about complex topics to a broader audience who are not familiar with some STS and anthropological concepts and discussions. “The blog posts are not supposed to be very long. I aim for two to four minutes of reading … I realized that people often don’t have time to read more than that, right?” says Dr. Tanja Ahlin.

Dr. Ahlin’s book is based on ten years of ethnographic research with Indian transnational families. These are families where family members live all around the world. The reason for migration is mostly due to work opportunities abroad. In her research, Dr. Ahlin looked at how these families used all kinds of technologies like mobile phones and webcams, the Internet, and Whatsapp, not only to keep in touch with each other but also to provide care at a distance. Dr. Ahlin conducted interviews with nurses living all around the world, from the US to Canada to the UK, the Maldives, and Australia. This varied and diverse field gave origin to the concept of field events that Dr. Ahlin develops in her work. In her work, Dr. Ahlin also developed the notion of transnational care collective to show how care is reconceptualized when it has to be done at a distance.

In sum, this episode of Platypod highlights how anthropologists come from different backgrounds and gives an honest overview of how we get to research our topics and occupy the spaces we do. We do not have linear stories, and that does not determine our potential. We at Platypod are very thankful for Dr. Ahlin’s time and generosity.

By Adrian Thorogood and Eva Winkler.

Our paper tackles a question that policymakers and public healthcare systems are wrestling with around the world: should for-profit companies be given access to medical data derived from patients for research?

In public healthcare systems, medical data is generated as part of the routine care of patients, and through administrative processes like billing and reimbursement. Medical data is a valuable resource for research and innovation that can advance medical science and improve healthcare. Beyond academic research, for-profit companies are increasingly interested in access to “real world” medical data to inform the discovery and development of drugs, medical technologies, and data-based health applications such as AI. Many countries are actively promoting data sharing to advance public health and wealth goals.

Despite this enthusiasm, for-profit re-use of medical data from public healthcare systems continues to be a source of controversy. Hospitals and data sharing initiatives have often been criticized for a lack of transparency and social license. Some have even been shuttered or sued. Empirical surveys consistently suggest patients and members of the public are less comfortable with companies accessing their sensitive health information than healthcare professionals or academic researchers. This tension between the interests of patients and those of the public and for-profit corporations calls for a closer look at the interests of all parties involved.

Inspired by political philosophy, our paper aims to identify and evaluate the competing claims of different stakeholders relating to for-profit re-use of medical data. This includes the patients providing data, the companies seeking to use data, the society who funds and relies on its public healthcare system, and the healthcare institutions and professionals who painstakingly generate medical data.

Patients have a right to have their medical data treated with confidentiality, and a right to actively determine who accesses this sensitive form of personal data and why. Any re-use of their data should be subject to strict privacy and security safeguards, and to high standards of consent, transparency, and accountability. Patients might expect to receive a direct share in profits generated from the contribution of data. Assuming such a scheme could be practically implemented, does this claim override those of companies, hospitals and society? We argue that this is a weak claim: while medical data certainly fall under patients’ control required by the right to informational self-determination, data are generated primarily for their healthcare and no right to share in profits can be deduced.

For-profit companies in the health sector do not have a right per se to access publicly funded medical data. However, they are entitled to freedom of research – a defensive right restricting state influence on research activities – and a right to a level playing field where access is provided (non-discriminatory access). Companies do have a legitimate right to pursue and realize profits from developing high-quality, life-saving or improving health products. Where products do not offer true value, are overpriced or are not domestically available, however, commercial practices can threaten the sustainability of health systems and patient access. This seems all the more unjust for products developed using data provided by health systems and patients. As part of corporate social responsibility, companies have ethical and reputational reasons to protect patient privacy and to deliver benefits to society, reflected by the current proliferations of guidelines around responsible AI.

Hospitals and clinics are ultimately the places where patient data is generated, through the dedicated efforts of healthcare professionals and staff. Do physicians and hospital leadership own the data and have a claim to share in eventual profits? These claims are complicated by the public funding supporting healthcare delivery, patient self-determination, and the fact that data generation is only the beginning of a complex value chain. They do, however, have a valid claim to appropriate compensation for data generation and curation, one that is all too often overlooked.

Society can benefit from for-profit re-use through things like improved drug safety, as well as more accurate and cost-effective care. How can the state ensure public funds invested in health systems and data infrastructure maximally benefit society, while also maintaining public and patient trust?

Two key tensions arise: between profit maximation versus societal benefit, and between commercial and societal interests in exploiting data versus patient self-determination and privacy. To address these tensions, we conclude by suggesting conditions for ethically sound for-profit re-use of medical data:

We conclude that there are good reasons to grant for-profit companies access to medical data if they meet certain conditions: among others they need to respect patients’ informational rights and their actions need to advance the public interest in better healthcare.

Paper title: Patient data for companies? – An ethical framework for sharing patients’ data with for-profit companies for research

Authors: Winkler EC1, Jungkunz M2, Lotz V1, Thorogood A3, Schickhardt C2

Affiliations:

Competing interests: ECW and CS have been receiving grants by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the frame of the German Medical Informatics Initiative (MII) and have been involved in the Working Group “Consent” of the MII

The post Patient data for companies: Patient privacy, private profits and the public good appeared first on Journal of Medical Ethics blog.

UPDATE: As a commenter helpfully pointed out, the person whose tweet I’m responding to was a political science Professor, not a historian. This kind of messes with the framing of this post but rather than stealth re-write it I’ll leave it as is and let you interpret my Freudian slip as you like

When I was in grad school, my Department’s grad student organization made shirts that read, “Political Science: Four sub-fields, no discipline.” Behind this joke is a common observation about political science, that it is defined by its focus rather than a formal set of methods or theories. Not everyone agrees with this characterization, and there have been some efforts to craft political science-specific tools. But generally political science is a field that draws on insights and tools from other areas to study politics. This is most pronounced in international relations. IR looks not just to other fields but also other sub-fields of political science to study the world.

Many present IR’s lack of discipline as a critique. They view IR scholars as a group of raiders, pillaging ideas and methods from other disciplines then returning to our barren homeland. Two recent Twitter kerfuffles, however, demonstrate that this aspect of IR is actually our greatest strength.

I don’t spend much time on Twitter anymore, but I still seem to discover the latest controversy. Two academic ones were related in their attacks on political science.

First, a historian responded angrily to a new article in the American Political Science Review by Anna Grzymala-Busse on European state formation. The historian suggested she used overly-simplistic methods to make a point that “real” experts on early modern Europe already knew (I’ve anonymized the tweet as I don’t like engaging in Twitter attacks).

This is a common complaint I’ve heard from historians studying international issues. IR and CP either take history’s insights and repackage them as our own, or don’t realize historians have already said this. Several academic institutions I’ve been a part of have included fierce and rather petty attacks by historians on political scientists.

As some respondents to this tweet noted, however, this historian isn’t really being fair. The role of religion in state formation is hardly settled ground–I took an entire class on debates over the role of religion in nationalism in grad school. Also, isn’t it a good thing to test and confirm certain arguments using a different set of data and methods? And when pressed, he couldn’t point to what historical works the author overlooked.

Critiques of IR and political science take the place of addressing real issues within other areas of study

In a follow-up tweet, the historian also makes an ironic call for interdisciplinarity. Ironic because this is an interdisciplinary work! Grzymala-Busse combined insights from comparative politics and history to generate new knowledge; this is in line with her other work, which involves careful attention to historical detail. Those calling for interdisciplinary engagement should cheer this, unless “interdisciplinary” just means listening to historians…

The second Twitter incident involved a data scientist. A data science grad student tweeted a broadside against the replication crisis in psychology, followed by attacks on political science and the social sciences in general. Another data scientist responded by pointing out that social scientists don’t conduct our own statistical analysis and instead get “real statisticians” to do it.

Again, people took issue with this. Some noted the data science grad student hadn’t really characterized the replication crisis accurately. Others asked for specific examples (which weren’t forthcoming). I’d also point out that it is true data science does have a real impact on our lives, but it’s hardly a positive one; one data science course I took focused on things like getting around CAPTCHA tests and tricking spam filters. And in practice “interdisciplinary” for data science often means using Python to study political or social issues without engaging actual subject matter experts.

These are very different controversies, and I’m sure these two people wouldn’t agree on much if forced to have a conversation. But both involve the perennial attack on political science (and IR by extension): we don’t come up with our own insights or methods, we just steal the former and implement the latter badly.

I thought of this debate recently while visiting the excellent Jorvik Viking Centre in York, England. The popular view of the Norse raiders known as vikings is of pillaging hordes, and that was certainly the case initially. But as often happens, they settled down. And in the case of Jorvik, they created a thriving cosmopolitan society enabled through their wide-ranging travels.

Maybe I’m pushing this metaphor a bit here, but I think of IR as Jorvik.

Yes, we got our start by combining economic models and humanistic insights. Yes, our research tends to include references from disparate traditions. Yes, our data is messier than other fields or even sub-fields within political science.

These issues all became strengths, however.

Because of IR’s broad roots we have to be conversant in different disciplines. When engaging with people from other disciplines, I often get the sense they’ve never really read anything from my field; their critiques are often caricatures. By contrast, many IR scholars are well-read in other fields.

Additionally, we recognize the difficulty of drawing on and testing different disciplines. That’s why you can find IR and political science discussions about combining methodologies or triangulating among competing schools of historiography.

Finally, the challenge of dealing with incredibly messy data has created problems for IR but also led to fertile debates. For example, the problem of selection effects in conflict onset has led to a useful back-and-forth.

Interdisciplinary means each side listens to and learns from the other, not that one asserts superiority and territoriality

Beyond that, these critiques of political science and IR take the place of addressing real issues within other areas of study. In C.P. Cavafy’s poem, “Waiting for the Barbarians” (which I referenced above) the inhabitants of a classical city sit and wait for the barbarians to arrive instead of dealing with the problems in their civilization. We can sense this in some of the attacks I’m discussing.

Historians are rightly frustrated at the lack of support for and interest in the humanities from universities and the general public. They often, however, see political science as the problem, such as Grzymala-Busse making a splash by engaging in historical debates. I am also reminded of a seminar my grad school put on to help students prepare and turn their dissertations into books; we went around the room discussing our topics and one history student made a crack about how “relevant” mine would be in DC. Rather than finding ways to demonstrate the value of a humanistic and historical approach to contemporary issues, some historians seem to blame political science and IR for sucking up all the attention (and student interest).

Likewise, data scientists are rightly tired of inadequate statistical models and badly interpreted findings. But what many of them seem to miss is that this is not a problem of stupidity: it is over-confidence, something data science tends to exhibit. I also sense a bit of frustration that political scientists are still seen as the expert on…politics despite our lack of cutting edge programming skills. This could be solved by closer collaborations between data scientists and subject matter experts, something that is often lacking.

It’s almost like political science and IR have become the Other to our critics, alleviating the need for any deeper reflection. As Kavafy ended his poem: “those people were a kind of solution.”

So what should be done?

Well, I am just finishing a fellowship at Edinburgh University’s Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (IASH), which was funded by the Centre for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World. It includes fellows from across the humanities, as well as the social and natural sciences. Part of the fellowship is a “work in progress” talk, which I gave last week. The empirical subject was my new work using social network analysis to study international religious politics, but the broader theme was my ongoing effort to test concepts from the humanities using quantitative social science methods.

I was unsure about the reaction. I didn’t know if the crowd of humanities scholars would react hostilely to me as an interloper. Instead, it was an incredibly fruitful discussion. There were tough questions and critiques, but they were in the spirit of collaboration and community. They recognized that I valued their disciplines, and they did not see the fact that I drew on theirs and mixed it with others (i.e., my lack of discipline) as a problem.

In this context, interdisciplinary meant each side listened to and learned from the other, rather than one asserting superiority and territoriality. It’d be nice if that attitude spread outside IASH.

By Gabriel Watts and Ainsley J. Newson.

Data obtained from genomic sequencing has an interesting quality. Unlike most other kinds of health results, the stored information remains accurate over time, because it reflects a largely stable property of our bodies: our DNA.

Of course, during this time, sequencing methods themselves are likely to have advanced further such that new sequence data will be of better quality. Much in the same way that the resolution on a phone camera picture from 2013 is not as good as one from today – indeed, we are already seeing changes to high-throughput DNA sequencing quality with the advent of long-read sequencing. But still, that present day sequence data can retain diagnostic validity for as long as a decade is already exceptional. In our paper in the Journal of Medical Ethics, we refer to this property as the ‘diagnostic durability’ of genomic data.

Another important aspect of genomic information is that while the sequencing data itself is stable, the interpretation of that data can be quite dynamic, and may change within a short space of time. This means a result delivered to a patient at one point in time may have a different interpretation later on.

For patients who receive results such as ‘no pathogenic (disease-causing) variant identified’ or who are told they have a ‘variant of uncertain significance (VUS)’, the changing status of this result can be significant. If a finding is re-graded, it may open up new treatment options that they couldn’t previously access. A result can also go the other way, to benign from VUS.

These attributes of genomic data have important implications for the responsible implementation of genomic testing in health. One question is: should laboratories or clinicians routinely go back to the data they hold for patients with null or VUS results, to see if a new interpretation is possible? We consider this question in our paper.

An immediate issue here is whether routine reanalysis is even feasible. On the one hand, doing this is known to increase the ‘diagnostic yield’ of genomic testing: more patients receive definitive information that can inform their treatment. Yet on the other hand, until automation of reanalysis is in place (and this is coming) this process is time- and resource-intensive, and likely beyond the majority of health systems to provide at large scale.

One way around this limitation is to only provide reanalysis to those who ask for it. But this is likely to limit this benefit to those who know to do it, or to ask for it, and so raises equity concerns.

One part of reanalysis, however, is reinterpretation of variant classifications. This process can achieve increased diagnostic yields in a comparable way to a detailed individual reanalysis. But it is more sustainable because it occurs at the level of classes of variant rather than individual patient DNA sequences. As such, routine reinterpretation of variant classifications may be more feasible at scale, at least in the short to medium term.

Given this, do laboratories or clinicians have an obligation to undertake routine reinterpretation of variant classifications as a part of the responsible implementation of genomic health care?

In our paper we argue against the existence of any general duty to reinterpret genomic variant classifications. Yet, we contend that a restricted duty to reinterpret ought to be recognised.

Our initial motivation was drawn from the intuitive pull of the position we argue against. It is undoubtedly ideal that diagnostic laboratories routinely reinterpret all their variant classifications, in order to keep up with the rapid changes in our understanding of genomic testing results.

It is a different question, however, whether there is a moral duty to do so. At issue here is whether the potential benefits of routinely reinterpreting genomic variant classifications is likely to lead to a valid diagnosis for any particular patient. If not, then it is arguably better to invest resources in preparing patients for the high likelihood that genomic testing will produce results that are uncertain, and that are statistically unlikely to become clinically relevant in the future, than to hold out of hope of a statistically unlikely diagnosis through regular variant reinterpretation.

To be clear, we are not arguing that we should not aim to develop diagnostic systems on which all genomic variant classifications are routinely reinterpreted. For instance, developing diagnostic systems that automate the various elements of reanalysis – including reinterpretation of variants classifications, but also the re-prioritisation of previously unanalysed sections of a patient’s genome, as well as the re-annotation of sequence data – is a morally laudable aim.

What we do argue is that the best healthcare systems need to be developed within the limits of what is currently or imminently feasible. As automation expands, the obligation to reanalyse may become actual. Our point is that we best not confuse this with an obligation arising from certain peculiar properties of genomic sequencing data. For any obligations here only stretch so far, and better warrant investment in patient counselling concerning the inherent uncertainty of genomic testing than investment in the routine reinterpretation of all variant classifications.

Paper title: Is there a duty to routinely reinterpret genomic variant classifications?

Authors: Gabriel Watts, Ainsley J Newson

Affiliations: Sydney Health Ethics, University of Sydney – Australian Genomics

Competing interests: None declared

The post Should we routinely reinterpret genomic results? appeared first on Journal of Medical Ethics blog.

I was just starting to wonder when the U.S. Department of Education would release a new year of College Scorecard data, so I wandered over to the website to check for anything new. I was pleasantly surprised to see a date stamp of April 25 (today!), which meant that it was time for me to give my computer a workout.

There are a lot of great new data elements in the updated Scorecard. Some features include a fourth year of post-graduation earnings, information on the share of students who stayed in state after college, earnings by Pell receipt and gender, and an indicator for whether no, some, or all programs in a field of study can be completed via distance education. There are plenty of things to keep me busy for a while, to say the least. (More on some of the ways I will use the data coming soon!)

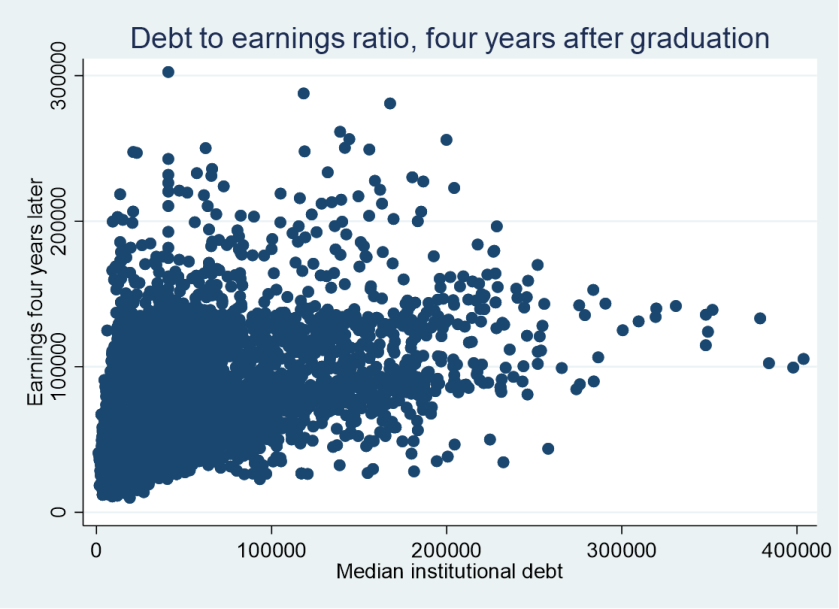

In this update, I share data on trends in debt to earnings ratios by field of study. I used median student debt accumulated by the first Scorecard cohorts (2014-15 and 2015-16 leavers) and tracked median earnings one, two, three, and four years after graduating college. The downloadable dataset includes 34,466 programs with data for each element.

The below table shows debt-to-earnings ratios for the four most common credential levels. The good news is that the average ratio ticked downward for each credential level, with bachelor’s and master’s degrees showing steep declines in their ratios than undergraduate certificates and associate degrees.

| Credential | 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | 4 years |

| Certificate | 0.455 | 0.430 | 0.421 | 0.356 |

| Associate | 0.528 | 0.503 | 0.473 | 0.407 |

| Bachelor’s | 0.703 | 0.659 | 0.569 | 0.485 |

| Master’s | 0.833 | 0.793 | 0.734 | 0.650 |

The scatterplot shows debt versus earnings four years later across all credential levels. There is a positive correlation (correlation coefficient of 0.454), but still quite a bit of noise present.

Enjoy the new data!

rkelchen

Enlarge (credit: NurPhoto / Contributor | NurPhoto)

After the Federal Trade Commission launched a probe into Twitter over privacy concerns, Twitter’s negotiations with the FTC do not seem to be going very well. Last week, it was revealed that Twitter CEO Elon Musk’s request last year for a meeting with FTC Chair Lina Khan was rebuffed. Now, a senior Twitter lawyer, Christian Dowell—who was closely involved in those FTC talks—has resigned, several people familiar with the matter told The New York Times.

Dowell joined Twitter in 2020 and rose in the ranks after several of Twitter’s top lawyers exited or were fired once Musk took over the platform in the fall of 2022, Bloomberg reported. Most recently, Dowell—who has not yet confirmed his resignation—oversaw Twitter’s product legal counsel. In that role, he was “intimately involved” in the FTC negotiations, sources told the Times, including coordinating Twitter’s responses to FTC inquiries.

The FTC has overseen Twitter’s privacy practices for more than a decade after it found that the platform failed to safeguard personal information and issued a consent order in 2011. The agency launched its current probe into Twitter’s operations after Musk began mass layoffs that seemed to introduce new security concerns, AP News reported. The Times reported that the FTC's investigation intensified after security executives quit Twitter over concerns that Musk might be violating the FTC's privacy decree.

Degree-educated millennials in London are 41 per cent less likely to own a home than degree-educated boomers were at the same age. And if you think that’s bad, pity the non-graduate under-40s in London, just 20 per cent of whom own a home (among non-graduate boomers of the same age, 60 per cent were homeowners).

Here is more from John Burn-Murdoch at the FT.

The post UK fact of the day appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

And perhaps it did not start in the United States? Here is more from David Rozado, including a full research paper:

Great Awokening is a global phenomenon. No evidence it started in US media. Analysis of 98 million news articles across 36 countries quantifies. Exception: state-controlled media from China/Russia/Iran using wokeness terminology to criticize/mock the Westhttps://t.co/yHwPMSR4D0 pic.twitter.com/RF30c2UmWQ

— David Rozado (@DavidRozado) April 6, 2023

The post Is the Great Awokening a global phenomenon? appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

This paper examines the authorship of post-publication criticisms in the scientific literature, with a focus on gender differences. Bibliometrics from journals in the natural and social sciences show that comments that criticize or correct a published study are 20-40% less likely than regular papers to have a female author. In preprints in the life sciences, prior to peer review, women are missing by 20-40% in failed replications compared to regular papers, but are not missing in successful replications. In an experiment, I then find large gender differences in willingness to point out and penalize a mistake in someone’s work.

That is from a new paper by David Klinowski. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

The post Do women disagree less in science? appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

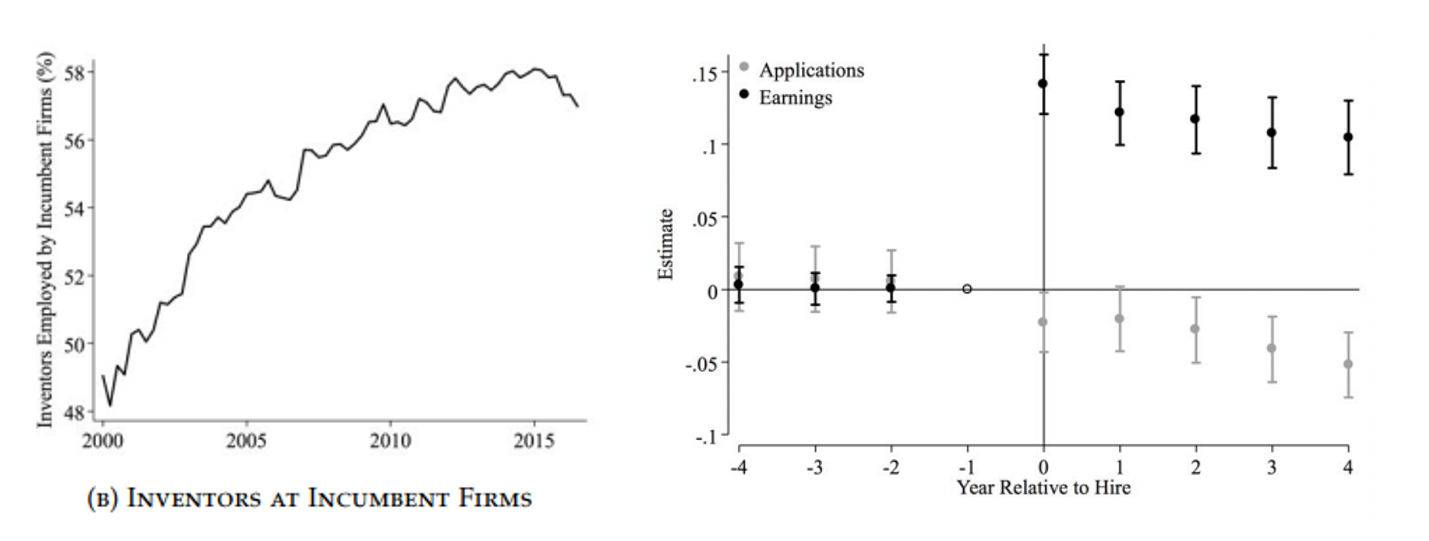

Ufuk Akcigit and Nathan Goldschlag (my co-author and former student) have an important new paper on the employment and invention dynamics of US inventors. Amazingly they link data on inventors from patents to census data using anonymized, person-level identifiers, known as Protected Identification Keys (PIKs) so they also have individual data on earnings and employment and they link that data to data on firms.

Ultimately, we observe the employment histories of approximately 760 thousand inventors associated with 3.6 million patents granted between 2000 and 2016.

What they find is twofold. First, an increasing number of inventors are being hired by large incumbent firms (left below). Second, when inventors move to large incumbent firms they earn more but they invent less, compared to similar inventors who go to young firms (right below). Why would an incumbent firm pay more for less productive workers? One possible answer is the Arrow replacement effect, namely a monopolist has less incentive to innovate than a competitive firm becasue the monopolist has a bigger opportunity cost, namely it’s own profits. As Arrow put it: “The preinvention monopoly power acts as a strong disincentive to further innovation.” A logical extension is that a monopolist will be willing to pay not to innovate and one way of doing that is to hire inventors who, if they worked at an entrant, would threaten their monopoly profits.

This is an important paper on declining dynamism in the US economy.

Addendum: In a second paper they use their extensive data to discuss the demographic characteristics of inventors.

The post The Arrow Replacement Effect and the Dynamics of US Inventors appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

The 2023 “QS World University Rankings” have been published. These contain rankings by subject matter, including philosophy.

The rankings are conducted by the London-based education firm Quacquarelli Symonds.

In the QS rankings, a school’s overall score for a particular subject is determined by a weighted formula that varies by area. In the arts and humanities, for the 2023 results, the formula used is: 60% academic reputation, 20% employer reputation, 7.5% citations per paper, 7.5% H-index, and 5% “International Research Metric“. (It is not clear why these factors are given these particular weights.)

QS does not specify whether its rankings are intended to assist prospective undergraduate or graduate students. The rankings have come under fire at various points for methodological concerns as well as conflicts of interest. Some of the results in philosophy will strike many readers as odd. So be aware that these rankings are controversial (as, of course, is the very idea of fine-grained rankings of places to study philosophy), and take note of alternative sources of information, such as departmetal websites, Academic Philosophy Data & Analysis and the Philosophical Gourmet Report (noting that various criticisms have also been made of the latter).

With those caveats in mind, here are the top 50 schools in the 2023 QS Rankings in Philosophy:

| Rank | University | Overall Score | Academic Reputation | Employer Reputation | Citations per Paper | H-index Citations |

| 1 | New York University (NYU) | 97.6 | 99.6 | 81.6 | 93.4 | 94.8 |

| 2 | Rutgers University–New Brunswick | 96.8 | 100 | 52.5 | 96.7 | 95.3 |

| 3 | The London School of Economics & Political Science | 94.3 | 96 | 98 | 88.5 | 85.4 |

| 4 | University of Oxford | 92 | 91.2 | 98.5 | 87.1 | 100 |

| 5 | University of Pittsburgh | 90.6 | 95.5 | 57.2 | 82.7 | 78.3 |

| 6 | University of Cambridge | 89.6 | 89.4 | 96.8 | 84.9 | 92.1 |

| 7 | Harvard University | 88.3 | 88.1 | 100 | 85.2 | 86.8 |

| 8 | Australian National University (ANU) | 88.1 | 88.2 | 88.6 | 87.9 | 86.8 |

| 9 | Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München | 87.8 | 89.7 | 81.4 | 80.3 | 84.6 |

| 10 | University of St Andrews | 87.5 | 89.5 | 75.5 | 82.3 | 83.8 |

| 11 | University of Toronto | 86.4 | 87.1 | 84.4 | 81.2 | 87.6 |

| 12 | University of Notre Dame | 86.3 | 88.3 | 65 | 82.1 | 86.1 |

| 13 | Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin | 86.1 | 87.6 | 77.6 | 83.2 | 82.1 |

| 14 | Princeton University | 85.5 | 84.2 | 82.6 | 91.9 | 90.2 |

| 15 | Yale University | 84.2 | 82.9 | 90.3 | 88.8 | 86.1 |

| 16 | Stanford University | 83.1 | 82.2 | 94 | 86.7 | 81.2 |

| 17 | University of California, Berkeley (UCB) | 83 | 82.6 | 83.9 | 85.4 | 82.9 |

| 18 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) | 82.5 | 78.5 | 93.4 | 100 | 89.6 |

| 19 | King’s College London | 82 | 81 | 83.2 | 84.5 | 86.8 |

| 20 | University of Bristol | 81.6 | 81 | 73.2 | 87.5 | 84.6 |

| 21 | The University of Edinburgh | 80.9 | 77.8 | 81.9 | 89.2 | 95.8 |

| 22 | University of Chicago | 80.2 | 80.6 | 83.2 | 80 | 76.1 |

| 23 | University College London | 79.9 | 77.8 | 82.5 | 86 | 88.3 |

| 24 | KU Leuven | 79.4 | 79.8 | 72.8 | 76.2 | 82.9 |

| 25 | Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne | 79.1 | 81.4 | 77.4 | 72 | 69.8 |

| 26 | Monash University | 77.9 | 74.4 | 86.8 | 92.6 | 84.6 |

| 27 | Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main | 77.8 | 80.4 | 48.2 | 78.6 | 72.5 |

| 28 | Macquarie University | 77.6 | 75.1 | 80.5 | 88.1 | 84.6 |

| 28 | The University of Sydney | 77.6 | 75 | 91.8 | 83.4 | 83.8 |

| 30 | Boston College | 76.8 | 79 | 64.3 | 73.8 | 69.8 |

| 31 | National University of Singapore (NUS) | 76.4 | 73.8 | 95.6 | 84.3 | 78.3 |

| 32 | Durham University | 75.8 | 74.4 | 71.2 | 83.8 | 80.2 |

| 33 | Université PSL | 75.7 | 75.3 | 68.3 | 78.4 | 79.3 |

| 34 | Central European University | 75.2 | 76.6 | 75.6 | 76.3 | 63.2 |

| 34 | University of Southern California | 75.2 | 71.5 | 73 | 92.1 | 86.8 |

| 36 | Sorbonne University | 74.8 | 76 | 78.9 | 68.6 | 69.8 |

| 37 | University of Amsterdam | 74.4 | 70.9 | 79.1 | 85.6 | 86.8 |

| 38 | Freie Universitaet Berlin | 74.3 | 75.6 | 69.1 | 74.4 | 66.7 |

| 39 | University of Leeds | 73.9 | 70.6 | 66.6 | 87.4 | 88.9 |

| 40 | University of Michigan-Ann Arbor | 73.8 | 70.4 | 75.2 | 89.9 | 82.9 |

| 41 | Lomonosov Moscow State University | 73.7 | 73.8 | 97.1 | 64.8 | 69.8 |

| 42 | Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain) | 73.5 | 77.4 | 67.8 | 63.4 | 56.7 |

| 43 | Wuhan University | 73.4 | 77.3 | 64.5 | 65.3 | 56.7 |

| 44 | Peking University | 73.3 | 75.3 | 83.9 | 67.1 | 59.1 |

| 45 | University of Turin | 73 | 74.2 | 63.3 | 67.9 | 73.8 |

| 46 | Fudan University | 72.8 | 77.2 | 77.2 | 59.4 | 51.2 |

| 46 | Universitat de Barcelona | 72.8 | 72.1 | 64.7 | 76.9 | 78.3 |

| 48 | University of Geneva | 72.4 | 70.6 | 63.9 | 82.8 | 79.3 |

| 49 | University of Vienna | 72.2 | 69.8 | 72.6 | 80.2 | 82.1 |

| 50 | Sun Yat-sen University | 72.1 | 74.8 | 50.6 | 69.6 | 65 |

You can see the rest of the philosophy rankings here.

What are the most-assigned films in college classrooms? Three film studies professors talk about the rankings and what they mean.

The post What Films Should We Teach?: A conversation about the Canon appeared first on Public Books.