Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

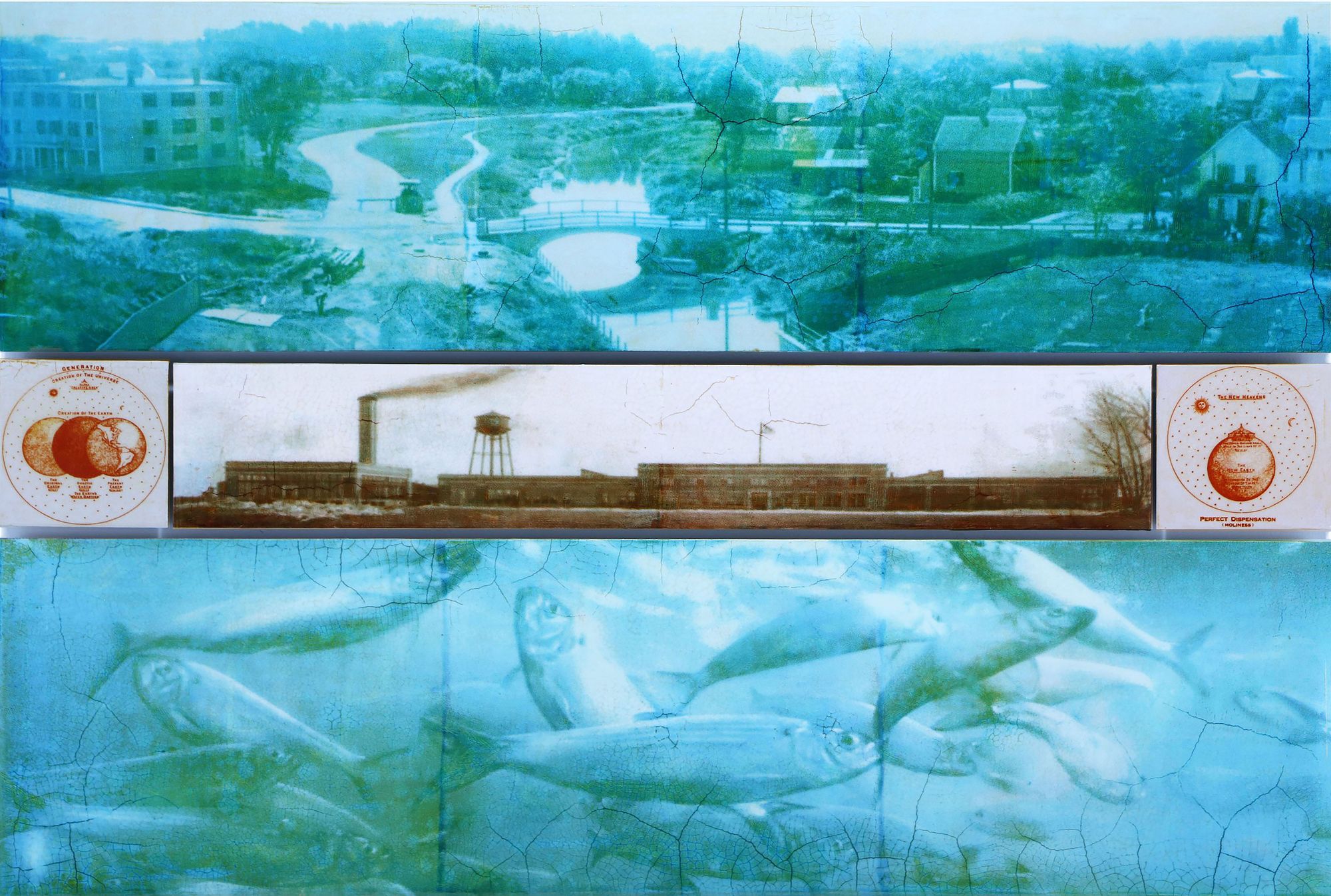

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

Relying on the private sector to decarbonize is a recipe for abandoning workers.

A global coalition of authors articulate the environmental violence of megafires by focusing on the myriad experiences of multispecies grief in their wake.

The post Multispecies Grief in the Wake of Megafires appeared first on Edge Effects.

Writer, rancher, and farmer Bryce Andrews discusses his newest book Holding Fire, which traces his personal story of grappling with the history of guns and violence in the American West.

The post Reforging Gun Culture in the American West: A Conversation with Bryce Andrews appeared first on Edge Effects.

Orans are sacred lands in the Thar Desert that are are being developed for wind energy projects. Nisha Paliwal argues that while wind energy is considered sustainable, it is experienced as violent extractivism by nearby village communities.

The post The Problem with Wind Farming on Rajasthan’s Sacred Lands appeared first on Edge Effects.

The concluding post from the author herself, drawing our symposium on The Ideal River to a close. Dr Joanne Yao is Senior Lecturer in International Relations in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London. Previously, Joanne taught at Durham University and the LSE, where she completed her PhD in 2017. Joanne was also one of three editors of Millennium: Journal of International Studies for Volume 43 (2014-2015) and is currently a member of Millennium’s Board of Trustees.Her research centers on environmental history and politics, historical international relations, international hierarchies and orders, and the development of early international organizations. The Ideal River is her first book; Joanne’s next project focuses on the history of Antarctica and early outer space exploration.

One question that repeatedly comes up from readers of this book is about its disciplinary identity. On the one hand, this is one of the book’s strengths – it seems to shapeshift across disciplinary boundaries and some of the central conclusions, particularly on the desire to control nature as a marker of a Western-led (imposed) modernity, might have been arrived at from a variety of different disciplinary starting points. On the other hand, this question puzzles me since the book is self-consciously situated in International Relations which is a clear path-dependent consequence of the intellectual riverbeds my own thinking has flown through. Perhaps what they wish to know is how did someone who started her academic life with the ‘Great Debates’ of IR end up contemplating the physical and metaphysical river (especially since I might have gotten ‘here’ more quickly and eloquently from elsewhere). But like all aspects of social and political life, we don’t get to re-run the experiment, and so this book is here, with its IR-warts and all.

But aside from my own intellectually situatedness, this book is a work of IR because, alongside the three rivers, international institutions are also pivotal characters in my story. Perhaps starting from IR, this point is obvious, and I felt the harder sell was to illuminate my three rivers as worthy protagonists in a story about international order. For this, I might have neglected my other characters.

International institutions have inspired less poetry than rivers, but what I want to show is that their veneer of technocratic dullness does not mean international institutions are devoid of poetry and the imaginaries that animate our dreams and nightmares of the future. The idea that international institutions or organizations can be purely technocratic and therefore apolitical and infinitely generalizable is as lofty an ideal as a river that is perfectly straightened and a frictionless conduit for global commerce. The ideal international institution does political work in that it prevents us from seeing the deeply ideological content of Harrington’s phrase ‘engineers rule the world’. And my hope is that by pinpointing how imaginaries of specific rivers influenced moments of institution-building at three 19th century diplomatic conferences, I can make some effort towards Harrington’s challenge to show when and how geographical imaginaries work (and save them from being relegated to that positivist dustbin of ‘epiphenomena’).

The ideal river and the ideal international institution are siblings conjoined at birth, and in constructing the ideal river, we as an international society are also trying to create the ideal international institution – one model built on all past human knowledge and expertise that can ensure peace and security across the infinite variety of human societies. It is the same grand vision that rests on the same totalizing logic and the same certainty that if we are clever enough and have big enough data, we can find a model that fits. Perhaps because the river is more concrete, it is easier to see the violence the ideal river does to actual rivers (and Danewid expresses this perfectly in comparing the caging of rivers to carceral capitalism), but I think equally, we can consider how the ideal institution does violence to everyday, lived institutions that flower around us. In this way, institutions are also assemblages in the way Phull describes the river, and that we can even think of braided institutions, to borrow from Phull’s (and Wall Kimmer’s) lovely imagery where we can imagine distinctiveness and harmony both at once.

An antidote to the destructive ideal river, Carabelli suggests, is a different way of loving the river. Rather than “projecting, assuming, and directing” the river in an effort to love it through control, Carabelli pushes us to listen, observe, and learn from the actual river to practice a love freed from the need to control. We might also make the same observation about institutions – that we engage in love as control by seeing international politics as solely problems that must be fixed through increased technical expertise. What would happen if we stopped to listen, observe, and learn from the infinite varieties of collective solidarities that have always already populated the international without a desire to fix, control, and master? Perhaps this is a first step towards what the international would look like while immersed in the river.

And, as Birkvad reminds us, in resisting the ideal river and ideal international institution, we must look both ways in time. It is just as easy to idealize an imagined future of straight lines and modern efficiency as a romanticized past where the river and society are frozen in the gauzy prison of nostalgia. Rivers and institutions interact and evolve, and a controlling love over either might seek to return them to an imagined mythical past. In my recent travels, I met a geographer in New Zealand whose research also focused on the ‘ideal river’, but his project looked backwards as different actors steering current river restoration efforts clashed over what they believed to be the ideal river. This romantic yearning for return, Birkvad warns us, can paper over oppression and injustices, and prevent the river and society from flowing and evolving. The question then, is how to look forward downriver without being ensnared by a singular idealized future, and how to recognize the past upriver without being held prisoner by it.

disorderedguests

Post #5 in our symposium on Joanne Yao’s The Ideal River, from Dr Giulia Carabelli. Giulia is a lecturer in Sociology and Social Theory in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London. She is interested in affect theory, nonhuman agencies, and social justice. Her current research project, Care for Plants, explores the shaping of affective and intimate relationships between humans and houseplants during the Covid-19 pandemic.

There are three protagonists in The Ideal River: the Rhine, the Danube, and the Congo. We meet them at different times in history when they become crucial agents in the (re)making of international orders. These three rivers illustrate different yet analogous processes of intervention aimed at domesticating what escapes human control (nature) to establish order as a matter of “progress”. As Yao argues, the taming of rivers exemplifies the “fulfilment of the Enlightenment promise that humanity stood together as masters over nature”, which is rooted in an unquestioned “optimism toward international progress” (186). The Rhine is the “internal European highway”, the Danube “the connecting river from Europe to the near periphery” and the Congo “the imperial river of commerce” (10). From the outset, the book sets expectations for nonhuman actors to take centre-stage in the recounting of history and to reveal their obscured roles in the development of global (human) politics. My reflections thus aim to discuss how the book foregrounds nonhuman agencies and to advance an argument for centring care and love to appreciate the potentially disrupting roles of rivers in reshaping political imaginaries, which become more and more urgent as that optimism towards human control flails.

1. The image of the river

I start from the cover of this book; an image taken by NASA/USGS Landsat 8 depicting the Mackenzie River in Canada. From above, this river is rendered through solid shades of blues, browns, and greens. This river does not flow. Similarly, when we imagine rivers on a two-dimensional map, they appear as homogeneous streams, whose ability to connect and serve human settlements we value. Such rivers become boundaries, obstacles, or opportunities to facilitate the movement of people, goods and capital, while ignoring their much more complex life as eco-systems in a constant process of change. These static representations of rivers, so instrumental to human life and its “progress”, become protagonists of the historical conferences discussed in the book. These rivers are ideals of what a river can become when understood as precious, yet disposable, resource.

Rivers on maps are what humans have long attempted to tame, because, as Yao discusses, to exercise control over nature ultimately proves, and provides, human progress. It drives and tests advancement in technology whilst gratifying the assertion of moral superiority. Clearly, this perspective results from thinking “human” and “nature” as dramatically different whereby the former is always standing above the ‘Other’; and to tame the Other for the sake of progress. The history of global politics, as shown vividly in this book, can be framed as the history of taming rivers. This is also the history of human faith in science and technology as the desperate attempt to prove that rationality is what sets us above all other species. It is the history of “transform[ing] irrational nature and society into economically productive and morally progressive units of governance” (200).

2. To tame and to care

Drawing on Zygmunt Bauman’s metaphor of European modernity as the impulse to “weed the social garden”, which engenders modern imperialism, scientific racism, and the Holocaust (31), Yao draws parallels between the taming of rivers and the taming of nature in the garden (Bauman 1989). The gardener becomes the emblematic figure of modernity – the one who transforms the wild into the familiar through a process of weeding. Crucially, to tame nature in the garden means to organise space according to a specific aesthetic that builds order by planting, pruning, or extirpating plants. What drives the gardener is the desire to make plants work and to become more efficient and productive. Yet, as many of us would know from having gardens or houseplants, it is by tending plants that we discover what the garden is, and what makes a garden a garden: a space we cannot fully control but that can surprise and mesmerise us.

The activity of caring for plants enables us to develop intimate relationships that are easily understandable through love. This is a love for disorder. It is a love that grows by letting go of control and accepting that the making of a garden is a collective activity where plans are shared and built with the plants. The garden is a story of compromise, conflict and love. The garden shapes us as gardeners, as much as we shape the garden to reflect our inner desires.

So how does it relate to the river?

3. On Love

What happens when we care for the plants in the garden, and to the life in the river, is that we appreciate them differently because we develop intimate and affective forms of attachment to them, which transform these nonhuman beings from objects to interlocutors. And here, I wish to focus on the tensions that love generates – between the love for order that comes from domination and the acceptance of disorder spurred by another kind of love.

As Yao highlights in her introduction, “to tame nature has not been confined to rivers and forests but also extends to ‘untamed’ elements in human society – indeed, to civilize the savage beyond the pale has long been a central aim and justification for colonial and imperial practices” (7).

I wish to connect this point on taming as a matter of civilisation with another argument made by Carolyn Ureña (2020), for instance, about colonialism and love – the coloniser/ the missionary are bound by the love for the uncivilised and it is their love that moves them to re-shape Indigenous lives to become more modern/ more rational/ more right. Thus, she concludes, love needs to be decolonised for love to be freed from desires of control. If we understand love as an affect that shapes relationality, the revolutionary potential of love exists in the possibility of love to make us realise that we cannot be in control.

To appreciate the river could become an act of love only if we switched our goals towards observing, listening, and learning rather than projecting, assuming, and directing.

If the modern love for rivers reflected the love for progress and order, which translated into a desire to tame them, how can we love rivers otherwise? Or, what makes a river a river?

4. Who is the river?

If only we immersed ourselves in the river, if we entered the water, we could see the plants, the animals, the limestone, soil runoff, sediments, minerals, and algae that colour rivers, making them blue or green or yellow and brown. The river is always changing; it moves, it transforms, and it does so relationally to the multiple human and nonhuman beings that coexist within its eco-system. Thus, to tame rivers can but be a delusion. We can only tame rivers when they are deprived of their life on flat maps.

Immersed in the river, we can create new connections that are affective, visceral, and potentially transformative. What, then, does the international look like while immersed in the river? What if, instead of drawing on rationality and science to transform the river into the ideal river, which means to cure the river from “its uselessness, laziness, and waste” (207), we could engage with the river by listening to what the river can teach us.

The book has started answering this question by accounting for Indigenous populations living with the rivers who nurture different relationships with their non-human kins. For example, for Native Americans activists at Standing Rock, the river is a nonhuman relative, who cannot be sold (214). Yao warns us from the dangers of essentialising Indigenousness “unfairly making them the bearers of responsibility for saving the destructive modern world from itself” (215), yet re-valorising Indigenous knowledge allows for important interventions in policy making. For example, the rights given to nature in Ecuador and Bolivia or those granted to the Whanganui River in New Zealand or the Ganges and the Yamuna in India (215). Although granting rights did not, especially in the case of Ecuador and Bolivia, stop extractive practices (Valladares and Boelens 2017), it remains a space where to start a conversation about “unlearn[ing] the ideational legacies of colonialism” (216) and the challenges faced when encountering the state in the process.

Crucially, the desire to tame rivers went along with the process of subjugating communities that stood by and with rivers – the “unimagined communities” that stand “on the way to progress” (208) . As the examples of the Narmada project in India and the Aswan Dam in Egypt illustrate, altering rivers destroy places “of cultural and spiritual importance and [the] communities that depend on them” (208). Yet, these colonising projects also serve as platforms to nurture river-human solidarity for mutual survival. Thus, rivers can become allies in resisting the violence of colonialism.

5. Conclusion

The nature we wish to tame is also the nature we come to love and desire. To tame nature becomes one with our love for an idealised form of nature that we wish to preserve and care for as a matter of ethics, and which becomes urgent at a time of environmental crisis.

Lesley Head (2016) discusses this as the paradox of the human in the Anthropocene;

“a time period defined by the activities and impacts of the human […] [and yet] a period that is now out of human control”. And for Head, the issue of climate catastrophe is emotional as we grief “our modern self, our view of the future as containing unlimited positive potential. We grieve a stable and pristine past” (Ojala 2017)

Thus, the importance of this book is not only in bringing attention to the historical contingencies that shaped human desires to tame rivers as part of the making of global orders. As Yao writes in the conclusion, the “climate crisis has highlighted [..] the catastrophic disconnect between the dream of Western modernity and the nightmare of ecological collapse”, which has been long in the making (219). Thus, the book should also be appreciated as a cautionary tale for imagining our future on this planet at a time when our society has become “disenchanted with the politics of climate change precisely because we are losing faith in the [promise of the] Enlightenment” (221). If we live in a time of change, one that brings more focused attention on the relational modes of worldmaking, we are then tasked with reflecting on what it means to engage with rivers, and by extension nonhuman actors, as political agents.

I conclude with a question: can our reflection on the international order ever account for the river as the river – without objectifying it but rather embracing the vitality of the river, its visions, needs and life?

disorderedguests

The third post in our series on Joanne Yao’s The Ideal River, today brought to you by Dr Kiran Phull. Kiran is a Lecturer in International Relations at the Department of War Studies, King’s College London. Her research centres on the politics of global knowledge production and the rise of opinion polling. She takes a critical and interdisciplinary approach to the study of public opinion, focusing on the ways that epistemic technologies (polls, surveys, population data) create and shape the conditions for governing social and political life. Previously, she was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the London School of Economics, where she received her PhD in IR exploring the history of scientific inquiry into Middle Eastern publics and the emergence of local emancipatory methods practices.

What does it mean to know a river? In its investigation of the taming of nature in the service of the modern international order, Joanne Yao’s The Ideal River reveals how international history is coursed by rivers. Yao’s meticulous weaving of institutional and imperial histories of the Rhine, the Danube, and the Congo offers a view of global governance that is both novel and necessary. By underscoring the co-conspiratorial relationship between science and empire, we learn how the construction of the ideal river was sustained by imperial infrastructures acting in concert with western scientific knowledge and practices. In exploring the development and institutionalization of these complex European river commissions as the first international organizations, The Ideal River asks us to contend with the centrality of scientific knowledge in configuring modern hydrological power relations. With a focus on cartographic representations, investigative commissions, scientific measurements, and industrial techniques of control, Yao deftly traces the epistemic drive that propelled empire ever-further downstream.

A core tension explored in the book is the unsettled dualism between science and nature. Here, Yao shows how the disciplining of nature’s waterways was implicated in the architecting of a global standard of sovereign rule and political legitimacy from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the context of Europe’s colonial ambitions, to know the river was to tame and lay claim to it. This reductionist view of progress through conquest was rooted in a Baconian scientific understanding of the world that sanctioned domination over nature in the service of human development. The discursive moves that allowed for modern scientific techniques and practices “to ‘force’, ‘compel’, ‘shackle’, and ‘tame’ the river” in pursuit of civilizational superiority reshaped these waterways into conduits for political power. Through Yao’s careful study of the disciplining of the “disorderly” Rhine and civilizing of the “mighty” Danube, it becomes clear how the construction of “the ideal river” was anchored in forms of knowledge that drained the river of its agentic lifeforce.

But how can we know a river if a river is never one thing?

The hypnotic image of the meandering ancient courses of the Lower Mississippi River defies the civilizational ethos that seeks to claim, pacify, and control the river through history. Mapped and visualized by the American cartographer Harold Fisk (1944), it depicts the many lives of the Mississippi over the course of thousands of years; its changing banks, altered paths, and iterative engravings marked across the landscape. “If a map is a projection of the world”, writes Tori Bush, “Fisk acknowledged the totality of the river in time and space and the absurdity of man’s attempt to control it”. Fisk’s rendering shows the folly in claiming to know the river as a singular, essential thing.

In a similar way, The Ideal River lays bare the absurdity of Europe’s efforts to civilize the Congo basin. Tracing colonial visions of the Congo as an empty cartographic space to be filled with European practices, institutions, commerce, and values, Yao simultaneously shows that it was the unknown Congo—i.e., what could not be mapped with western epistemic authority—that remained a source of fear for Europe. At the same time, the spurious assumptions that underpinned the construction of the colonial Congo constrained the possibilities for constructing what Yao sees as a more holistic understanding of the river.

For Yao, the holistic river acknowledges its inextricable natural and social entanglements, along with the indivisibility of the human and more-than-human. In this way, the ideal river becomes more than a geographic and political imaginary. We might think of it as a hydro-assemblage of human and nonhuman actants: water, colonial governance, energy, techniques of measurement, diplomatic meetings, cartographic innovations, vessels, rationality, commercial cargo, pollution, official treaties, dams, trade routes, floods and falls, engineers and explorers, kinetic force, myths and frontiers, bound together in a complex configuration of animate power. Their fluid dynamics compel us to think of the river as multiple and ever-changing.

Reflecting on the changing nature of the river coursing through history, I was reminded of the river of my hometown. A particular viaduct that passes over the urban Don River in Toronto reads: “This river I step in is not the river I stand in”. This idea is attributed to the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 500 BCE), who tells us that everything in its essence is change, and that change is the only constant. The same river cannot be stepped in twice, for it is always organically in motion. Knowledge of the river is never guaranteed. The unfortunate story of the Don River, like so many others, is indeed one of change.

Once home to the Indigenous Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Huron Wendat communities, the Wonscotanach was captured by British settlers in a colonial landgrab that saw the river and its dependents suffer the afflictions of settler modernity. Castigated by its industrial proprietors, the river was branded both defiant and unimpressive, lacking the power-generating capacities that would render it profitable, and thus useful. As the city grew, its river died. Through the 19th and early 20th centuries, the river was repeatedly reimagined as a better one by way of reengineering plans to straighten, reroute, fill, bury, or otherwise change its nature. Indeed, it was believed that the river’s true potential could only be unlocked when “the right men appeared, possessed of the intelligence, the vigour and the wealth equal to the task of bettering nature by art on a considerable scale”. In return for its perceived disobedience, the river and its accompanying valley became a site of refuse; home to pollutants, vagrants, wartime labour camps, disease, prisoners, and social outcasts. In the 1960s, the river was eclipsed by the construction of an adjacent superhighway—an arterial stretch of asphalt, concrete, industrial lighting, and the incessant din of ultra-fast traffic skirting the edge of the Don. In this way, the highway became a better river—one that serviced the urban heartspace with more speed, efficiency, and power.

Contemporary ambitions to re-vitalize and re-naturalize the ecology of the Don—to return to it the life that was taken—are again changing its shape and trajectory. But Heraclitus’ river motif bears revisiting: it is the pristine image of a river’s natural and organic flowing waters, securing everything in a state of change, that conceals the tireless pulse of human intervention driving and disturbing this flow.

Can we know a river in new ways? There’s a kind of river termed a braided river, where currents course through channels layered upon channels, creating fluvial networks of entwined waterways that form and flow independently yet as one. This energetic weaving of streams and brooks takes shape instinctively over time, inscribing the earth’s surface with the best possible combination of vectors towards a lower elevation. En route, they split, stray, and merge in ever-shifting ways, creating impermanent islands of sediment, leaving behind an ephemeral plaited pattern. The metaphor of the braided river complements Yao’s vision of a world that one day embraces the multiple ontologies of the river. Untethered from “the spell of European Enlightenment thinking” and its associated values of scientific rationality and civilizational standards, multiple forms of knowledge might coexist, converge, and diverge with an awareness of the oneness of their collective motions. Amidst the looming ecological and governance challenges of the Anthropocene, this braiding of knowledge and experience becomes a crucial step toward any possibility of collective living. This calls to mind Robin Wall Kimmerer’s poignant Braiding Sweetgrass (2013), where the possibilities of deep reciprocity between indigenous ways of knowing and scientific knowledge raise hopes for a better world, one less intent on claiming to know the world objectively, and more on relational knowing in and with the world. In challenging the epistemic disciplining of the river in modernity, The Ideal River restores an untold history to the study of global governance and international organizations, opening space for a more relational and compassionate politics. Ultimately, Yao entreats us to dim the relentless beat of modern progress “that drives us to derangement”, and to instead listen for the latent polyrhythms, contingent histories, and kaleidoscopic changes that constitute a river in motion.

disorderedguests

The second post in our symposium on Joanne Yao’s The Ideal River.

This one is from Dr. Cameron Harrington, an Assistant Professor in International Relations at the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University. His research centres on the shifting contours of security in the Anthropocene, with a particular focus on the concept and practices of water security. His work has appeared in journals such as Millennium, Global Environmental Politics, Environment and Planning E, Critical Studies on Security, and Water International. He is the co-author of Security in the Anthropocene: Reflections on Safety and Care (2017, Transcript), and is a co-editor of Climate Security in the Anthropocene: Exploring the Approaches of United Nations Security Council Member-States (forthcoming 2023, Springer).

While studying at my alma mater, Western University, in Canada, I would frequently run into the same graffiti scribbled across bathrooms, classroom desks, library walls, and study spaces.

ERTW.

It wasn’t a secret code or the mark of an exclusive academic society. In fact, you could see it emblazoned on the back of t-shirts handed out to hundreds of freshman students every year.

Engineers Rule the World.

The idea that engineers – and by extension engineering – are, in fact, responsible for holding society together, is a powerful boast. It certainly helped young undergraduate engineering students construct an image of their studies as immensely important. While the rest of us spent our days studying the words of long-dead philosophers or burrowing deeper into arcane debates about “the international order,” these intrepid future engineers would learn to do the real work of building the world that we all inhabit. No engineers, no world.

I was reminded of this slogan – ERTW – as I read through Joanne Yao’s book, The Ideal River: how control of nature shaped the international order. Yao’s book is a richly detailed examination of the various imaginaries, schemes, and tools that propelled European efforts across the nineteenth century to tame – to engineer – nature. Yao argues that the desire to control nature reflected and refracted a larger modernist “faith in science and rationality to conquer the messiness of entwined social and natural worlds…” (pg. 36). This ability to control a wild and unpredictable nature was one key standard by which civilization could be judged. Her account focuses on the social and material construction of three specific rivers: the Rhine, the Danube, and the Congo. Though each river was imagined uniquely, they all became embedded within a larger modernist political project of world-building. From these rivers emerged the first modern manifestations of what we now term international organizations.

This is, then, another story of Enlightenment-bred confidence in the ability to overcome nature’s “limits”.

Yet Yao’s nuanced account pushes further. She shows how geographical imaginaries of nature and civilization propelled Europeans and their allies to not only bend the rivers to their needs but also shaped the ideas of what a civilization’s needs were in the first place. The effects of this interplay are now deeply rooted within key IR concepts and institutions. They frame a dominant understanding of political purpose and state legitimacy as the fixing, controlling, and defending of territorial boundaries (cf. Ruggie 1993). The cases also show how a vision of political authority legitimated through the control of nature became universalized at the same moment it was dispersed unequally around the world through a hierarchical relationship between core and periphery. Yao’s archival research, which she combines with gothic literary criticism (yes, really), shows how imaginaries of the ideal river – wild entities tamed through science and engineering to serve human progress and economic development – drove the formation of the first modern international organizations. While Yao is careful not to draw a straight line from the 1815 Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine to the creation of the United Nations, the international agreements and Commissions which formed along these rivers do expand our understanding of the history of global governance. Yao concludes her book by connecting these stories to the contemporary shape of water security and ecological sustainability as objects of contemporary global governance.

This last point is perhaps the book’s most ambitious and compelling. Today, frequent alarms are raised about the perilous state of global water resources and the inherent risks to human, national, and international security which emanate from this. The dominant governance discourse surrounding water, despite a number of alternative interventions, continues to emphasise its potential as a driver of either conflict or cooperation in a world of worsening scarcity. We are frequently warned that water’s volatile mixture – its importance, scarcity, and its failure to respect political boundaries – means conflict will inevitably emerge. That, or humanity’s shared reliance on water can lead to the interdependent peace we’ve been promised again and again. All we need to do is get the right institutions in place or start valuing water properly. In both cases, water – whether it is to be fought over or shared via institutions, laws, and balanced economic valuation – is rendered as timeless, natural, and inert. There is an ontological stickiness to water and waterways which holds them as distinctly modern entities.

The concept of “modern water” has been developed by critical geographers over the last two decades. It explains how our contemporary understanding of what water is represents only one, albeit hegemonic, way of knowing and relating to water. According to Jamie Linton modern water is a “pure hydrologic process” (2014, 113), which has roots “originating in Western Europe and North America, and operating on a global scale by the later part of the 20th century” (2014, 112). Modern water is divorced from any social or ecological context, existing as a singular, pure resource that is available to be exploited.

Much of the recent western academic interest in the ontology of water can be traced back to an influential article published in 2000 by the science historian Christopher Hamlin. In it, Hamlin showed how this master narrative of modern water emerged at a specific time and place, namely in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. “Premodern waters” were diverse, heterogeneous entities which could never be found pure in nature. They displayed infinite “aspects of the histories of places” (Hamlin 2000, 315). One need not read deeply across classical and medieval history or religious texts before coming across references to the varied properties of different waters found in rivers, streams, mountains, wells, etc.

Two key events mark the emergence of modern water. The first came in the 1770s when work by scientists such as Antoine Lavoisier and Joseph Priestley showed that all waters were in fact derived from a single compound of oxygen and hydrogen. The second moment arose when John Snow famously discovered he could arrest the spread of cholera in London in 1855 by removing the handle of the water pump on Broad Street. In so doing, water became a simple substance, “whose most interesting quality was its pathogenic potential” (Hamlin 314).

These two moments alone are, of course, insufficient for explaining the shift to modern water and should be situated within the larger geohistorical context. Yet, in Europe by the end of the 19th century, the premodern idea that waters were many had clearly been supplanted by a new type of water: singular, knowable, manageable. This shift was propelled by a larger Enlightenment ethos that placed its faith in science to overcome a messy and irrational world. As Jeremy J. Schmidt describes it, “out went water sprites and multiple ontological kinds of water, and in came chemistry, physics, and engineering” (2017, 28).

The contours of this paradigm shift drive Yao’s narrative. She draws from James Scott’s seminal work, Seeing Like a State, to show how the emergence of the modern state arose through techniques that made irrational nature legible to new forms of governance. The Rhine, Danube, and the Congo rivers were each brought under the calculating eye of the state (and empire) through various bureaucratic and engineering practices. The engineers straightened the Rhine to improve its commercial potential. The geography of the Danube offered the opportunity to expand western European civilization to its near-periphery, taming the physical danger of flooding while also securing it from the moral dangers emanating from the distorted, semi-familiar frontiers to the east. Finally, European bureaucrats and diplomats thought it their moral duty to impose a colonial system of control over the Congo that would enable free navigation and trade. This depended upon infrastructural projects like ports, roads, and railways that would transform the Congo (and Africa) from a conceptually empty space into one bursting with European free trade and civilization. Together the cases show how water became modern and the modern state (of IR) became riverine.

While not using the concept explicitly, Yao’s book is a rich historical account of the formation of what critical geographers call hydrosocial territories. According to Boelens et al (2016) these are the spatially-bound, multi-scalar, socio-ecological networks of humans and water flows. The consolidation of a hydrosocial territory is mediated by a complex interplay between social imaginaries, political hierarchies, and technological infrastructure. Hydrosocial territories consolidate a particular order of things. In 19th Century Europe, they emerged from various techniques, including the deployment of specific geographical imaginaries and vast engineering projects to position and order humans, nature and thought within a global network of modern water. From this process emerges the early forms of global governance.

One of Yao’s key arguments is that this process of hydroterritorialization was deeply contingent upon the political activation of specific geographical imaginaries. This is because a river’s geography must be imagined before it can be governed.

Yet, at the risk of contradicting myself, the reliance on imaginaries is troublesome. Conceptually, imaginaries are often left underdeveloped and the power attributed to them overstated. They are relied upon to account for an awful lot. This may be the point. The sociologist Johann Arnason (2022, 13) has called them “a crossroads concept”, able to tie together and anchor a variety of metaphysical and political concerns. Charles Taylor famously developed the idea of social imaginaries as an answer to the problem of explaining “that largely unstructured and inarticulate understanding of the whole situation, within which particular features of our world show up for us in the sense they have” (2007, 173).

Imaginaries are increasingly used by IR and politics scholars to explain diverse phenomena and across vastly different contexts. Their power and influence almost limitless, imaginaries can travel back and forth across time and space, moving in almost quantum-like ways to mimic or create different realities. The Rhine was imagined as economic highway, the Congo as an abstract, empty colonial space. Yet, these seemingly vastly different imaginaries led to similar political projects and the first attempts at establishing modern international organizations. If imaginaries truly play such a decisive role in the political processes of institutionalization, then more explicit theoretical and empirical work is needed that shows how and why. Or, put another way, a key puzzle presented in The Ideal River is how the endless creative potential of the imagination was so narrowly expressed through political, institutional, and infrastructural expressions of modernity. Thus, further work might explore how the imaginaries themselves are transformed, oppressed, modified, or contested through the genesis of specific political and material projects.

As it stands, in all cases and across time periods, imaginaries make everything possible, including every subsequent practice and process. Their malleability is alluring but that same flexibility risks conflating a number of other dimensions of social and political life. They all get ensnared in the net of the imaginary. Do these engineers, artists, policymakers, and colonial bureaucrats always, necessarily require a geographical imaginary to get on with other things like practice, habit, prejudice? There is a distinct risk from scholars fixing an ontological permanence to imaginaries as a constitutive energy and thereby inadvertently reinscribing the same totalizing logics of modernity.

Near the end of The Ideal River, Yao (207) quotes the German engineer, Otto Intze, who proclaimed in 1902 that the key to taming a river was presenting “water with a battleground so chosen that the human comes out the victor.” The battleground would be large dams, built to discipline the river and physically bend it to the will of civilization. From this martial framing sprung the still-dominant approach to modern water management. All the dams subsequently constructed around the world thus represent the apotheosis of modern water and its conquering of alternative water ontologies. These hydraulic infrastructures are the “technological shrines” (Kaika, 2006) to modernisation and scientific progress. But one need not gaze upon these massive infrastructural shrines to understand the creation, spread, and influence of modern water. Instead, you need only look at the scribblings on creaky desk at the back of a university classroom.

ERTW.

They say that no river ever really ends. The engineers probably agree.

Bibliography:

Adams, S., & Arnason, J. P. (2022). A Conversation on Social Imaginaries: Culture, Power, Action, World. International Journal of Social Imaginaries, 1(1), 129-147.

Boelens, R., Hoogesteger, J., Swyngedouw, E., Vos, J., & Wester, P. (2016). Hydrosocial territories: a political ecology perspective. Water international, 41(1), 1-14.

Hamlin, C. (2000). ‘Waters’ or ‘Water’?—master narratives in water history and their implications for contemporary water policy. Water Policy, 2(4-5), 313-325.

Kaika, M. (2006). Dams as symbols of modernization: The urbanization of nature between geographical imagination and materiality. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(2), 276-301.

Ruggie, J. G. (1993). Territoriality and beyond: problematizing modernity in international relations. International organization, 47(1), 139-174.

Schmidt, J.J. (2017). Water: abundance, scarcity, and security in the age of humanity. New York University Press

Taylor, C. (2007). A Secular Age. Harvard University Press.

disorderedguests

The Disorder of Things is back, and with a symposium too. Over the next week we’ll feature a succession of posts on Joanne Yao’s The Ideal River: How Control of Nature Shaped the International Order, followed by a rejoinder from Joanne herself (the full set of posts will be available in one easy spot here). The first post is an introduction to the book and commentaries from George Lawson. George is Professor of International Relations at the Australian National University. He is a global historical sociologist who works primarily on revolutions. His most recent books are: On Revolutions: Unruly Politics in the Contemporary World (with Colin Beck, Mlada Bukovansky, Erica Chenoweth, Sharon Nepstad and Daniel Ritter) (Oxford, 2022), and Anatomies of Revolution (Cambridge, 2019).

Writing from the frontline of anthropogenic climate change, in Australia, I don’t need any convincing about the co-implication of nature and politics. I live in Canberra – Australia’s ‘Bush Capital’ – a planned city in the Scottian mould, nestled amidst nature reserves, organised around an artificial lake supported by a major dam project, and home to a large number of predators, both human and otherwise. When I moved to Canberra nearly three years ago, the major (non-artificial) lake that welcomes visitors to and from Sydney, Lake George, was empty – the result of decades of low rainfall generated by human-induced climate change. Following three years of La Nina weather patterns, which has brought persistent rain that locals never tire of telling our family we brought with us from Britain, Lake George looks more like an inland sea. But not for long, it seems. Models suggest that this year will see a return to dry conditions, perhaps even a drought. So: no more Lake George.

Outside Canberra’s old Parliament House, which was replaced by a snazzy, environmentally friendly upgrade in 1988, can be found the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, the oldest continuous protest site in the world. Some of the demands made by aboriginal Australian groups, including those who people the Embassy, as well as those involved in discussions around the Uluru Statement from the Heart and current debates about a First Nations Voice to Parliament, begin by acknowledging the co-implication of land, custodianship and sovereignty. Understandings of citizenship in Australia are intimately tied up with claims about the relationship between nature and political authority.

These entanglements between nature and politics are found not only in Australia, of course. As Giulia Carabelli points out in her essay in this symposium, they animate protests in North Dakota and India, have been part of legal debates in Ecuador and Bolivia, and can be found in disputes over the rights of natural objects, including rivers.

Rivers are the subject of Joanne Yao’s wonderful The Ideal River, a book that is – as each of the contributors to this symposium acknowledge – expansive in scope, richly researched and judiciously curated. But Yao’s book is not just about rivers, it is also about the wider relationship between nature and politics and, in particular, the ways in which Enlightenment understandings of science and rationality underpinned international ordering projects over the past two centuries. These projects to ‘tame nature’, Yao argues, were foundational to the construction of a standard of civilisation through which Western polities ordered relations between each other and the peoples they subjugated through imperialism and colonialism: The Rhine was the ‘internal European highway’, the Danube the ‘connecting river from Europe to the near periphery’, and the Congo ‘the imperial river of commerce’. Enlightenment principles of mastery over nature were tied to scientific techniques and ideas of progress in projects that stratified peoples and places around the world. In this way, rivers serve as the elemental source of global governance. For Yao, the taming of nature is a distinctly modern project, one bound up with ideas of mastery and ordering, power and civilisation, rationality and progress.

If rivers and forums of global governance are conjoined twins of the Enlightenment, one modern family member that receives less attention in The Ideal River is capitalism. As Ida Danewid points out in her essay, and as Yao recognises in her response, rivers were imagined as ‘frictionless highways that were to carry commerce, civilization, and Christianity to the world’s unpropertied peripheries’. Despite noting the commercial features of hydro-ordering, and their necessarily extractive, dispossessive properties, capitalism plays a muted role in Yao’s narrative. Sorting peoples into civilized and uncivilized quotients had many dimensions: racial, religious, and more. But a crucial element concerned levels of ‘development’. In Australia, for example, claims of aboriginal sovereignty were often denied on the basis that aboriginal nations were insufficiently ‘developed’ – in other words, they did not support individual property rights or sufficiently ‘advanced’ commercial practices. Here, as in other parts of the world, the standard of civilisation was organised, in significant measure, through capitalist logics – and egregiously misapplied to experiences on the ground in order to dispossess and subjugate First Nations peoples.

A further issue raised by Yao’s interlocutors arises from her interest in the distinctly modern co-location of science, nature and political authority. To contemporary eyes, Wittfogel’s notion of ‘hydraulic empires’ contains deeply problematic Eurocentric associations with ‘oriental despotism’. And rightly so. Nevertheless, it is worth reflecting on the age-old harnessing of water for political claims-making, and the development of scientific advances to do so. No doubt these dynamics have taken novel forms in modernity. But the binding together of science, nature, polity formation and extraction is a long-running entanglement. This raises a linked question about whether the modern standard of civilisation itself changed over time. I wonder whether the ordering of the Rhine in the early part of the 19th century was as severe as the ordering of the Danube in mid-century and, even more so, the Congo in the 1880s? During the course of the century, as modern capitalism became more extensive and ideas of ‘scientific’ racism hardened, so global hierarchies themselves shifted. Not all ordering projects sorted peoples with the same intensity or through the same logics. And not all wildernesses were considered to be equally wild.

The relationship between imaginaries and political projects forms the basis for Cameron Harrington’s contribution to the symposium. Harrington raises the question of why the ‘endless creative potential of the imagination’ became ‘narrowly expressed’ in particular political projects. After all, there was not one ‘modern imaginary’. As Ida Birkvad persuasively argues in her essay, not only was the Enlightenment not a single thing, but modernity also reconfigured a brand of romanticism that venerated nature. In this sense, ‘the time of the first river commissions described in The Ideal River was as much the era of Romanticism, as it was that of Enlightenment rationality’. Today, the sanctification of nature is often associated with protest movements, particularly those by indigenous peoples. Yet, as Birkvad notes, the romanticisation of the past can itself be a political project that maintains and reinforces existing hierarchies and exclusions. Here anti-developmentalism stands as a form of, rather than in opposition to, ordering projects that meld science, nature and political authority.

This speaks to a more complex association between nature and politics than is sometimes apparent. In her essay, Kiran Phull captures this complexity through the notion of the ‘braided river’ – an assemblage of interweaving waterways that ‘split, stray, and merge in ever-shifting ways’ and, in the process, generate a ‘plaited pattern’. This unruly, yet patterned, formation is one that resonates with contemporary concerns over the entanglement of nature and politics, constituted as it is through a complex, multi-scalar tapestry of the global, the transnational, the regional, the national, and the local. Contemporary global governance too is a dense web of overlapping administrative forums. One of the achievements of Yao’s book is to see this dense web as bound up with hydraulic infrastructures. This leaves open the question of what political projects will emerge from the various, often contradictory, imaginaries that bind together science, nature and international politics. Far from occupying spaces of ‘technocratic dullness’, Yao points – quite rightly – to their ‘poetry and imaginaries that animate our dreams and nightmares of the future’. What would happen, she asks, if we stop to ‘listen, observe, and learn from the infinite varieties of collective solidarities that have always already populated the international without a desire to fix, control, and master’? What indeed …

disorderedguests

Mollie Holmberg takes crip lessons from philosopher Val Plumwood's experience of being prey to a crocodile, pointing toward strategies for collective pandemic survival and resistance to environmental violence.

The post Pandemics, Predation, and Crip Worldings appeared first on Edge Effects.

Prison Agriculture Lab directors Carrie Chennault and Josh Sbicca discuss the ubiquity of carceral agriculture in the United States, its structuring logics of racial capitalism, and possibilities for abolitionist food futures.

The post Mapping the Unfree Labor of Prison Agriculture: A Conversation with Carrie Chennault and Josh Sbicca appeared first on Edge Effects.

Big trees, old trees, and especially big old trees have always been objects of reverence. From Athena’s sacred olive on the Acropolis to the unmistakable ginkgo leaf prevalent in Japanese art and fashion during the Edo period, our profound admiration for slow plants spans time and place as well as cultures and religions. At the same time, the utilization and indeed the desecration of ancient trees is a common feature of history. In the modern period, the American West, more than any other region, witnessed contradictory efforts to destroy and protect ancient conifers. Historian Jared Farmer reflects on our long-term relationships with long-lived trees, and considers the future of oldness on a rapidly changing planet.

Real estate developments emulating U.S.-style master-planned communities are popular in Buenos Aires. Mara Dicenta unpacks the violence such developments enact on the environment and the community, as well as the resurgence against them.

The post The Violence of Gated Communities in Buenos Aires’s Wetlands appeared first on Edge Effects.

NASA has launched an innovative air quality monitoring instrument into a fixed-rotation orbit around Earth. The tool is called TEMPO, which stands for Tropospheric Emissions Monitoring of Pollution instrument, and it keeps an eye on a handful of harmful airborne pollutants in the atmosphere, such as nitrogen dioxide, formaldehyde and ground-level ozone. These chemicals are the building blocks of smog.

TEMPO traveled to space hitched to a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launching from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. NASA says the launch was completed successfully, with the atmospheric satellite separating from the rocket without any incidents. NASA acquired the appropriate signal and the agency says the instrument will begin monitoring duties in late May or early June.

Spacecraft separation confirmed! The Intelsat satellite hosting our @NASAEarth & @CenterForAstro#TEMPO mission is flying free from its @SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and on its way to geostationary orbit. pic.twitter.com/gKYczeHqV5

— NASA (@NASA) April 7, 2023

TEMPO sits at a fixed geostationary orbit just above the equator and it measures air quality over North America every hour and measures regions spaced apart by just a few miles. This is a significant improvement to existing technologies, as current measurements are conducted within areas of 100 square miles. TEMPO should be able to take accurate measurements from neighborhood to neighborhood, giving a comprehensive view of pollution from both the macro and micro levels.

This also gives us some unique opportunities to pick up new kinds of data, such as changing pollution levels throughout rush hour, the effects of lightning on the ozone layer, the movement of pollution related to forest fires and the long-term effects of fertilizers on the atmosphere, among other data points. More information is never bad.

TEMPO is the middle child in a group of high-powered instruments tracking pollution. South Korea's Geostationary Environment Monitoring Spectrometer went up in 2020, measuring pollution over Asia, and the ESA (European Space Agency) Sentinel-4 satellite launches in 2024 to handle European and North African measurements. Other tracking satellites will eventually join TEMPO up there in the great black, including the forthcoming NASA instrument to measure the planet's crust.

You may notice that TEMPO flew into space on a SpaceX rocket and not a NASA rocket. This is by design, as the agency is testing a new business model to send crucial instruments into orbit. Paying a private company seems to be the more budget-friendly option when compared to sending up a rocket itself.

This article originally appeared on Engadget at https://www.engadget.com/nasa-launches-powerful-air-quality-monitor-to-keep-an-eagle-eye-on-pollution-170321643.html?src=rssNASA TEMPO launch

The NASA TEMPO launch seen at night from a distance, with the rocket blazing as it takes off.

The United States supported a coup in Honduras in 2009. Fast forward a dozen years, and the Latin American country finally escaped the repressive thumb of far-right administrations when a leftist president — and the country’s first female head of state — was elected. She promised reform, including as it pertains to the mining sector, which has devastated portions of the country’s environment and used horrific violence to suppress its opponents. As Jared Olson details, however, hope soon faded:

They blocked the road with boulders and palm fronds. They unraveled a long canvas sign, bringing the vehicles to a stop — a traffic jam that would end up stretching for miles. Drivers stepped out into the oppressive August humidity, annoyed but not unaccustomed to this practice, one of the only ways poor Hondurans can get the outside world’s attention. Several dozen people, their faces wrapped in T-shirts or bandannas, some wielding rusty machetes, had closed off the only highway on the northern coast. It was the first protest against the Pinares mine — and the government’s failure to rein in its operations — since Castro came to power eight months before.

Things weren’t going well. That Castro’s campaign promises might not only go unfulfilled but betrayed was made clear that afternoon last August when, as a light rain fell, a truck of military police forced its way through the jeering crowd of protesters and past their blockade — to deliver drums of gasoline to the mine.

Since their creation in 2013, the military police have racked up a reputation for torture and extrajudicial killings as a part of its brutal Mano Dura, or iron fist, strategy against gangs. Though it earned them a modicum of popularity among those living in gang-controlled slums, they also became notorious for their indiscriminate violence against protesters, as well as the security they provided for extractive projects. They’ve faced accusations of working as gunmen in the drug trade and selling their services as assassins-for-hire. The unit was pushed by Juan Orlando Hernández, now facing trial in the United States for drug trafficking, while he was president of the Honduran congress, in his attempt to give the military power over the police — his “Praetorian Guard,” in the words of one critic.

Castro had been a critic of the unit before her election. But after a series of high-profile massacres last summer, she decided that — promises to demilitarize notwithstanding — the unit would be kept on the streets. And here they were, providing gasoline and armed security to a mining project mired in controversy and blood.

John Lewis-Stempel visits Ashdown Forest in Sussex, England, to closely observe a 300-year-old oak tree (Quercus robur). From first light until midnight, Lewis-Stempel describes the animals, birds, insects, and flora that depend on it in careful detail. In addition to astonishing you with the sheer variety and volume of creatures that inhabit and visit the tree, this piece will gently slow your heartbeat. You’ll feel your shoulders loosen as you follow Lewis-Stempel’s keen observations. It’s exactly the type of relaxation meditation we can all use.

7.01 am

The leaves of autumn, brought down by the screaming Halloween wind, still lie around the tree in a thick sodden copper mat; the mould is soft on the pads of the returning vixen as she slinks down into her den among the tree’s roots, a rabbit clamped in her jaws from her night prowl. A present for her cubs.

5.16 pm

The ecology of the oak tree is a game of consequences: the newly emerged leaves of the oak are eaten by the pale-green caterpillar of the wintermoth, which, in turn, feeds the blue tit, whose brood has just hatched in yet another of the tree’s cavities; the sparrowhawk, terror of the copse, flashes between the tangled branches, to catch and feed on the blue tit.