About twenty years ago, in an essay on Henri Lefebvre, I said that his book on Nietzsche (1939) was on the prohibited ‘Liste Otto’. These were books that had to be removed from sale, and existing copies destroyed, after the German occupation of France. For other reasons now I’ve recently looking at the list – the 1940 version is here – and discover that this is not one of the books on the list. Mea culpa.

As far as I can tell, only two books written by Lefebvre are on the list – there are various iterations from 1940 and through the occupation. The books are Hitler au pouvoir (1938) and Le Matérialisme dialectique (1940). So too was Cahiers de Lénine sur la dialectique de Hegel (1938) and Karl Marx’s Morceaux choisis (1934), both of which Lefebvre and Norbert Guterman had edited.

Guterman was Jewish, so this alone would have been enough for inclusion on this list. But Lefebvre’s book on Nietzsche, his Le Nationalisme contre les Nations (1937) and the collection of texts by Hegel he and Guterman had edited (1938) are not on the lists I’ve seen, and nor is their co-authored book La conscience mystifiée (1936).

There is therefore something of an arbitrary nature of the list – there are obviously reasons why the Nazi occupiers would object to those they did include, but those reasons would also seem to apply to ones they did not. The Nietzsche book, for example, is very much written as a challenge to the fascist appropriation.

In looking further into this, though, I went back to the original edition of Critique de la vie quotidienne from 1946. On the page ‘Du même auteur’, Lefebvre lists his previous publications.

There he distinguishes three ways his books were suppressed.

Interestingly, he says Le Nationalisme was in the first category; Hitler and Nietzsche in the second; Le matérialisme dialectique and the collections on Lenin and Hegel were in the third. From the lists I’ve seen, this isn’t entirely correct either for category three, but it explains why the Nietzsche book was indeed removed from sale shortly after publication, and why copies are so hard to find today. And presumably the ‘Liste Otto’ did not need to proscribe books that were already banned.

The list of books by Lefebvre ‘En préparation’ is also interesting – only a few of these were ever published, but that’s another story, some of which also concerns censorship.

I hope what I’ve reported here is accurate, but happy to receive additions or corrections.

Incidentally, my 2004 book on Lefebvre has long been available as print-on-demand only, and keeps going up in price. Someone has uploaded a version here though…

stuartelden

Three books that were on the list - Le matérialisme dialectique is a later reprint

three books that were not included on the list

Edgar Landgraf, Nietzsche’s Posthumanism – University of Minnesota Press, September 2023

While many posthumanists claim Nietzsche as one of their own, rarely do they engage his philosophy in any real depth. Nietzsche’s Posthumanism addresses this need by exploring the continuities and disagreements between Nietzsche’s philosophy and contemporary posthumanism. Focusing specifically on Nietzsche’s reception of the life sciences of his day and his reflections on technology—research areas as central to Nietzsche’s work as they are to posthumanism—Edgar Landgraf provides fresh readings of Nietzsche and a critique of post- and transhumanist philosophies. \

Through Landgraf’s inquiry, lesser-known aspects of Nietzsche’s writings emerge, including the neurophysiological basis of his epistemology (which anticipates contemporary debates on embodiment), his concerns with insects and the emergent social properties they exhibit, and his reflections on the hominization and cultivation effects of technology. In the process, Landgraf challenges major commonplaces about Nietzsche’s philosophy, including the idea that his social theory asserts the rights of “the strong” over “the weak.” The ethos of critical posthumanism also offers a new perspective on key ethical and political contentions of Nietzsche’s writings.

Nietzsche’s Posthumanism presents a uniquely framed introduction to tenets of Nietzsche’s thought and major trends in posthumanism, making it an essential exploration for anyone invested in Nietzsche and his contemporary relevance, and in posthumanism and its genealogy.

stuartelden

On 19 May 2023 I’ll speaking at a workshop on Translation and the Archive in the Continental Tradition, organised by Henry Somers-Hall for Royal Holloway, University of London. It will be held in central London at Senate House. Registration is free, but required via Eventbrite.

The other speakers are Alan Schrift on Nietzsche, Daniel Smith and Charles Stivale on Deleuze and Julia Ng on Benjamin. My talk will be “From the Archive to the Edited Translation: Lefebvre, Foucault, Dumézil”.

We have put together this workshop to explore those aspects of the project of philosophy that are often seen as simply the groundwork or condition for the philosophical project itself, namely those processes of translating, editing, compiling, and those of the archive, both its constitution and consultation. This workshop will explore themes of the nature and operation of these processes in the continental tradition, both in terms of how they constitute the territory of philosophical thought, but also the ways in which the specificity of continental philosophy affects the process of translation, and how these projects of translation have affected the philosophical work of the translators themselves.The workshop brings together a number of internationally recognised researchers to discuss the role of these themes in their own work, both as translators and editors, and as thinkers.

The workshop will take place in Senate House, Central London, on May 19th, 2023.

stuartelden

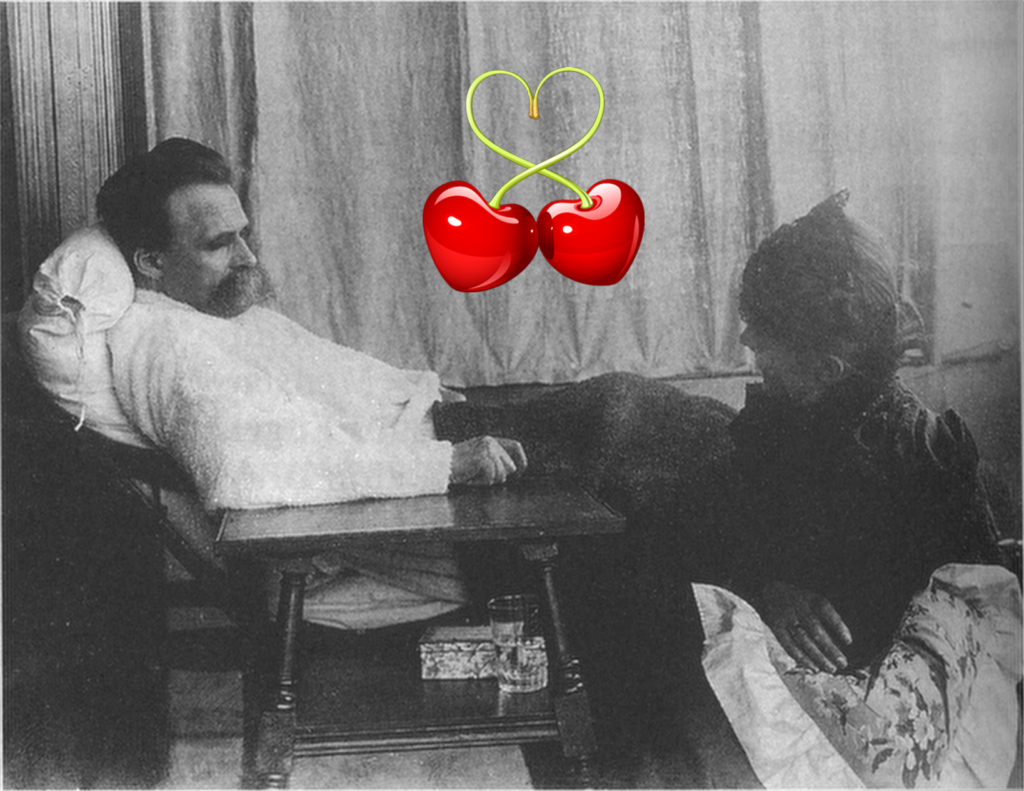

Hans Olde, from “Der kranke Nietzsche” (“The ill Nietzsche”), June–August 1899. Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv Weimar.

After two vodka tonics and a cosmo, my ninety-year-old grandmother lifts her glass and says, “But you know that Nietzsche is my boyfriend?”

“He is?”

“He’s my boyfriend.”

It’s all right—we’ve shared boyfriends before. The actor Javier Bardem. Errol Louis, anchor at NY1. Her new neighbor. Her many doctors. She tells me that Nietzsche is her boyfriend because Nietzsche also hates the German composer Richard Wagner. I tell her Nietzsche hates a lot of people. She nods. “That’s good in a man.”

Earlier in our dinner I’d mentioned I was finally reading Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist—two white-hot texts that serve, in part, as the ecstatic summation of much of Nietzsche’s previous work. Both works glow with special invective. The usual targets are abused (Socrates, Kant, et cetera). So are George Sand, George Eliot, and, of course, generally happy people: “Nothing could make us less envious than … the plump happiness of a clean conscience.” It’s in Twilight that Nietzsche announces, “The man who has renounced war has renounced a grand life.”

Would he be a good boyfriend? He’d be a fierce one, often railing at the “radical and mortal hostility to sensuality.” He’d remind you: “When a man is in love he endures more than at any other time; he submits to anything.” Would he wink? Probably not.

Freud claimed, apparently, that Nietzsche “had a more penetrating knowledge of himself than any man who ever lived or was likely to live.” In these final writings it is clearer than ever how Nietzsche’s “hate” evolves out of a prolonged annoyance at knowing people—and history and philosophical systems—better than they know themselves. You sense the loneliness of this awareness. Nietzsche needs his supernatural, self-generating heat, lest his flame down there wither in the wild pits of instinct. (“Nothing ever succeeds which exuberant spirits have not helped to produce.”) If he was your lover, he’d remind you, his torch high, that “one must be superior to mankind in force, in loftiness of soul—in contempt.” Those who cannot achieve this are “merely mankind.”

I look at my grandmother, whose awareness—as Nietzsche might recommend—seems to recede from the outside world as it advances internally. She closes her eyes. I think she’s slipped under when she points at me. “First it’s our Spanish fellow. Then that other fellow. Then Nietzsche.”

—Sophie Madeline Dess, author of “Zalmanovs”

A friend whose taste I trust recently recommended Denton Welch’s 1945 novel In Youth Is Pleasure, a beautiful little book and one of my favorite discoveries of 2022. Welch’s writing is impressionistic, playful, homoerotic, dreamy, often hilarious, and at times ecstatic. What plot there is centers on the fifteen-year-old Orvil Pym, who is spending the summer holiday with his father and brothers at a hotel in Surrey several years before the outbreak of World War II. Orvil’s mother has died; his feelings for his siblings and for his father (who has bestowed upon him the nickname “Microbe”) range from vague fondness to childish terror and loathing. Often Orvil is left alone. He eats pêche Melba (“‘It’s like a celluloid cupid doll’s behind,’ said Orvil to himself. ‘This cupid doll has burst open and is pouring out lovely snow and great big clots of blood’”); he spies jealously on a schoolmaster reading Jane Eyre to two boys, one of whom appears to be taking a particular kind of gratification from the experience; he desecrates a church with libidinal glee, throwing himself on a brass statue and kissing its face “juicily.” At the end of the day, Orvil always seems to be consuming oozing cakes in the hotel dining room, dressed in mud-stained clothes.

This is a lonely book, and a remarkable one for the way in which its sensuality emerges: from inside this loneliness. Orvil takes an aesthete’s pleasure in the physical world but also in the eruptions of his own consciousness; much of the novel’s eroticism arises from his encounters with a kind of other within the self. Desire, enchantment, the delights of reverie and of metaphor—these spring from within. Floating alone along a river, Orvil thinks, “I’m like one of those Baked Alaskas … one of those lovely puddings of ice-cream and hot sponge.” Here, loneliness can be devastating, mischievous, grotesque, monstrous, thrilling—but it is never grim.

—Avigayl Sharp, author of “Uncontrollable, Irrelevant”