Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

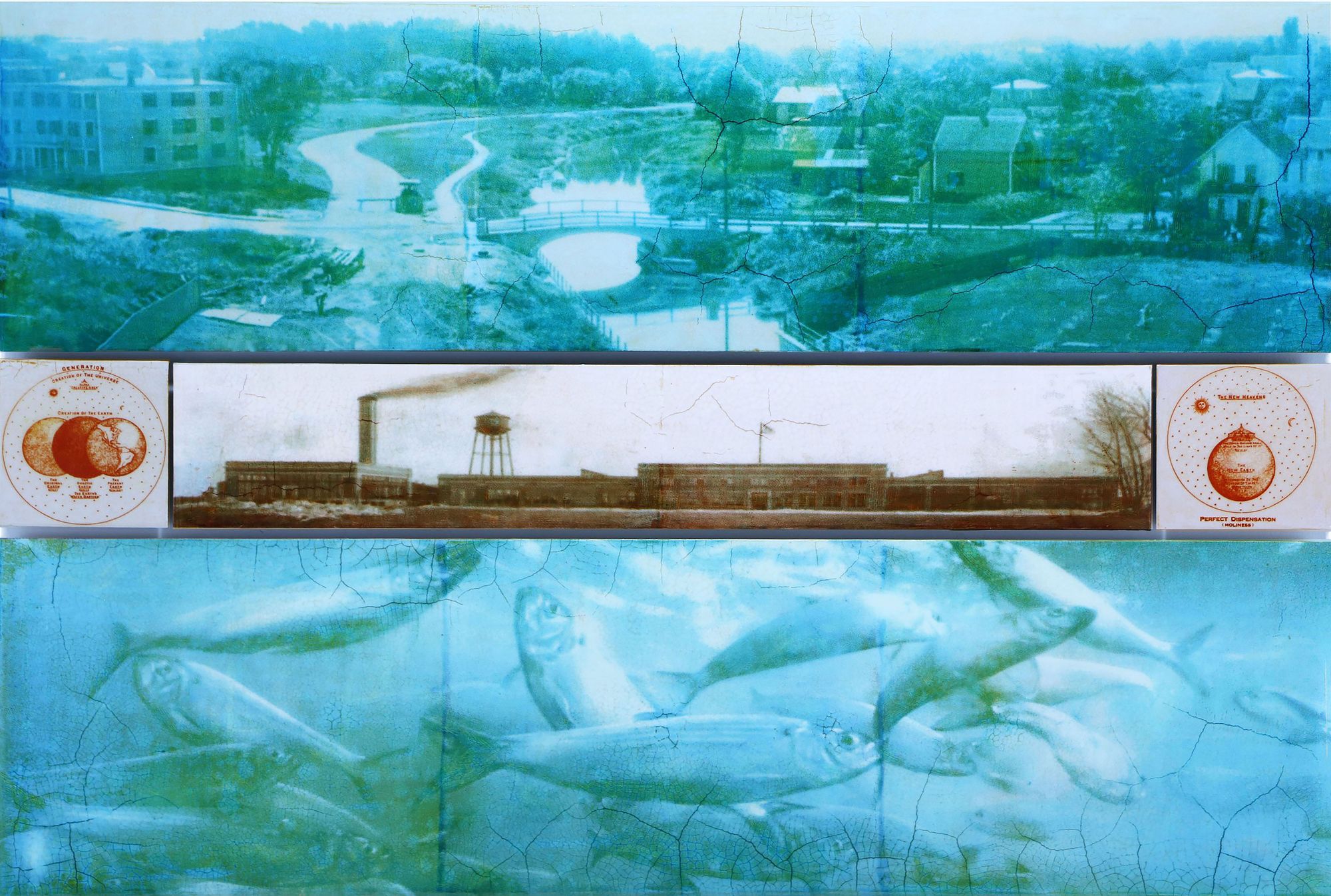

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

The ORCID US consortium, managed by Lyrasis, is five years old in 2023 - hear about their progress so far and plans for the future in Alice Meadows' interview with their PID Program Leader, Sheila Raybun

The post The ORCID US Consortium at Five: What’s Worked, What Hasn’t, and Why? appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

The Directory of Open Access Books (DOAB) is celebrating its 10-year anniversary, a great opportunity to reflect on how far we have come with open infrastructures for the distribution and discoverability of open access books (monographs, edited collections, and other long-form publications).

The post Guest Post — Towards Global Equity for Open Access Books appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

"Researchers have only so many hours in a day; if they can spend one less hour on a research article because we have implemented improved workflows and better technology, that’s one more hour they can spend on research to try to save my life, and the lives of all ALS patients." In today's post, Bruce Rosenblum shares his experience as a clinical trial participant and how that contributed to scholarly publications.

The post Guest Post — Being Research Data appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Is there value to be found in national, or language based preprint servers? Matthew Salter discusses lessons learned from the first year of Japan's Jxiv.

The post Guest Post — A Year of Jxiv – Warming the Preprints Stone appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Biosphere 2 was built in the late 01980s by the most unlikely group: a cast of creatives, a charismatic philosopher-king, a financier, theater nerds, and an amazing crew of engineers. The idea behind Biosphere 2 (Biosphere 1, of course, being the Earth) was to build a self-contained structure and set of systems that could test the idea of a self-contained space colony, albeit one that was anchored to the earth. In 01991, just four years after construction began, B2 was launched: a team of Eight “econauts” were sealed into the three-acre habitat, along with a Noah’s ark-load of life. Ostensibly, the challenge was simply to see if they could survive.

A team from Long Now arrived in Oracle, Arizona to tour Biosphere 2 on the evening of October 26, 02022, just as the sun was setting. We were there to investigate: to see if there were lessons that we could extract from B2 and apply at Long Now, specifically to the Clock of the Long Now. We all had done our homework and watched Spaceship Earth, the excellent new documentary that retells the B2 origin story. But nothing can really prepare one for the experience of encountering B2 in person.

Oracle, Arizona, is a long way from anywhere. The Sonoran Desert is a reasonable analog for the surface of Mars. And the ziggurats of steel and glass rise above the high plain like an American Giza.

The point of the original Biosphere 2 was bold, but straightforward enough. It was an experiment to see if it would be possible to create a self-contained ecosystem – one large enough to support the lives of the team inside. It was a space station, right here on Earth. And yet, right away, we had so many questions:

Like, why was there what seemed to be a vent at the top of the pyramid? Why install a vent on a closed system?

And what was that UFO-like object peeking out from behind the main pyramid?

These and other questions would have to wait until morning.

The next day, the team gathered for a tour given by John Adams, the Deputy Director and Chief Operations Officer of the facility. He explained that the tower structure that had so puzzled us the day before was, in fact, an observation tower. It was assumed that the original inhabitants of B2 would need a place to retreat to where they could observe “Biosphere 1” – the earth that they had left behind. The vent was installed to cool the glass pyramid, which, in reality, became a giant solar oven in the middle of the desert whenever the sun shined through it— which, in Arizona, was essentially every day. The vent was a striking reminder that B2 is rarely operated as a completely closed system. The ambition to study earth in a hermetically-sealed system has largely been supplanted by a more practical use for the facility: an ecological laboratory that can control more variables than nature allows. Under the auspices of its new owner, The University of Arizona, B2 is now mostly operated as a very large greenhouse, but it has the capability to do far more.

Biosphere 2’s 676,000-gallon “ocean” is the site of some rather significant science. It was here, in the living coral reef that lives under the faux ocean, that scientists proved that there was a direct connection between the increasing levels of CO2 in the atmosphere and decreasing coral calcification rates. There is currently an effort to breed and genetically engineer corals that can survive climate change – and those corals will be tested at B2 before being released into the open oceans.

The rainforest is also the site of important climate change research. Climate modelers have subjected it to drought, to floods, to higher-than-normal temperatures, and to atmospheres with higher-than-normal CO2 concentrations. The point is not to see what happens to the B2 rainforest per se, but rather to validate and calibrate the predictions that the climate models are pumping out about the fate of real rainforests during the coming Anthropocene.

B2’s former agricultural areas, the greenhouses where the original econauts grew their food, are now home to L.E.O.: the Landscape Evolution Observatory. L.E.O. has been called the first step in a new science of terraforming planets – which sounds exciting, but in practice boils down to watering sand and then watching that sand slowly turn into soil. Earth scientists have used B2 to watch dirt “grow” for eight years now. Next year they’re going to sprinkle some hay seeds over the newly-formed soil and see what happens.

The tour really got interesting when we were led into the life support system under Biosphere 2 – the so-called technosphere.

At the end of the tunnel is a giant variable volume chamber. It’s a “lung” that, when the biosphere is sealed up tight, fills and contracts with air. Remarkably, the sealed biosphere still loses less air by percentage volume than the International Space Station. When the sun rises, so does the lung’s 40-thousand-pound metal roof, which is attached to the walls by a flexible rubber membrane. And then when the sun sets, the roof settles back in place. Without the lung, B2 wouldn’t have lasted a single day – the windows would have shattered due to the changing atmospheric pressure inside.

As we wandered the grounds, it became apparent what an impressive feat of engineering Biosphere 2 was — and still is.

That evening, we gathered to consider what we saw at Biosphere 2. When B2 was first in the news back in 01991, it was hailed as a visionary piece of engineering which, by its very existence, asked us to understand ourselves differently. Biosphere 2 was the whole earth under glass, a miniature model of Spaceship Earth. We were meant to understand that while the econauts sealed inside were LARPing a trip across our solar system, the rest of us were not players in a play. We really were on board a ship, eight-thousand miles across and traveling at sixty thousand miles an hour around the sun – and the idiot lights on the life support system were, and still are, blinking red. B2 was a mammoth piece of engineering which embodied a philosophy, a point of view, a warning. And now? While B2 had been made scientifically useful, we all saw what was lost, too. Biosphere 2 has lost much of its original poetry and, with that, has largely fallen out of the conversation.

So, the question came back to us. How do we ensure the Clock of the Long Now doesn't suffer a similar fate?

Rebecca Lawrence discusses how connections across all aspects of the system are needed for open research to flourish and deliver upon its promise.

The post Guest Post — Why Interoperability Matters for Open Research – And More than Ever appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

“If you are a car owner, you are red meat for whoever wants to prey upon you, whether it is police, auto lenders, or state agencies.”

The post Car Creditocracy: An Interview with Julie Livingston & Andrew Ross appeared first on Public Books.

Wiley's Jay Flynn discusses the impact that paper mills had on Hindawi's publishing program and how all stakeholders must collaborate to address behaviors that undermine research integrity.

The post Guest Post — Addressing Paper Mills and a Way Forward for Journal Security appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Reporting on a Mellon-funded open access monograph pilot, UNC Press Director John Sherer notes successes and remaining challenges.

The post Guest Post — Open Access for Monographs is Here. But Are we Ready for It? appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Part three of a three-part series aims to discuss the topic of advancing accessibility within scholarly communication with the focus of digital accessibility.

The post Guest Post — Advancing Accessibility in Scholarly Publishing: Recommendations for Digital Accessibility Best Practices appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Part two of a three-part series aims to discuss the topic of advancing accessibility within scholarly communication with the focus of digital accessibility.

The post Guest Post — Advancing Accessibility in Scholarly Publishing: Building Support appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Part one of a three-part series aims to discuss the topic of advancing accessibility within scholarly communication with the focus of digital accessibility.

The post Guest Post — Advancing Accessibility in Scholarly Publishing: Fostering Empathy appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Space exploration in northern Sweden often gains meaning in relation to mining. In this blog post, I ask: how does mining serve as a “speculative device” (McCormack 2018) for envisaging a future beyond Earth? I was drawn to the topic of outer space infrastructures by the Swedish Space Corporation’s ongoing expansion of its rocket launch site, located outside the subarctic city of Kiruna. This expansion aims to turn what has thus far been a sounding rocket range into a full-fledged launch site for small satellites, undertaken in anticipation of a dramatic increase in the demand for launch services over the forthcoming decades. The land occupied by the spaceport and its impact area, twice the size of Luxembourg, interferes with the reindeer herding lands of four Sámi villages. In early 2022, I traveled to Kiruna to begin inquiring into the politics of space exploration in Sweden, focusing in part on the relation between the launch site and the reindeer herders. Yet, eluding my questions about space and instead shifting the conversation to mining, several of the herders I spoke with urged me to consider how outer space was often shot through the region’s long-running history of underground resource extraction.

In his book Space in the Tropics, Peter Redfield (2000) investigates the relation between two seemingly separate phenomena in French Guiana: an old penal colony that operated between 1852 and 1943, on the one hand, and the contemporary spaceport from where the European consortium rocket Ariane is launched, on the other hand. Redfield (2000: xiv) asks, “what might it reveal that [these] different things happen in the same place?” The same question can be posed about mining and space in Kiruna, where the city’s surrounding landscapes have long been presented by the Swedish state as resourceful and available for exploitation. Inspired by Redfield’s question, here I attend to a series of negative, positive, historical, and “speculative relations” (Ojani 2022) between mining and space as invoked by reindeer pastoralists, local residents, politicians, and space actors in subarctic Sweden.

For reindeer herders working within the launch site’s impact area, space sometimes held a oppositional relation to mining in that the spaceport helped keep new mining initiatives at bay. In a context long characterized by resource extraction, discrimination, and marginalization, one exploiter prevents herders’ ever-shrinking grazing areas from further destruction by other exploiters. While often critical of its placement on their lands and the various forms of disturbance created by its surrounding infrastructure, the herders occasionally emphasized the launch site’s utility. For example, only a few years ago, it became the reason for halting mineral prospecting in the area. Hence, while some of the herders expressed deep anxiety about falling rockets near their animals, others were quick to point out that they were in fact fortunate to have a relatively good collaboration with the Swedish Space Corporation. In response to my queries about space, the herders switched to other, more pressing concerns: mining initiatives located outside the spaceport’s impact area, tourism and the increasing use of snowmobiles on their herding lands, and hunters who were lobbying against a state initiative to increase herders’ influence over hunting licenses, among several other issues.

In contrast, local space actors and politicians saw a potentially allied relation between mining and the space industry, calling for stronger synergies between the two. These actors frequently underscored that both industries are not only “hi-tech” but also operate in “extreme environments,” above the atmosphere and below the ground. For them, the connection between mining and space seemed almost self-evident, and there had already been several collaborations between the two industries. For instance, local scientists conducted an experiment using a sealed-off mining area for the detonation of dynamite, the vibrations of which were then measured with infrasound microphones attached onto stratospheric balloons. And as it turns out, the analogy often drawn by my interlocutors between space and the underground is not in any way unique to this particular setting. It also predicates space analogues undertaken in cave-environments elsewhere in the world (see Park 2016).

A MAXUS rocket with the iron ore mine visible in the background. Photo by the author.

But the relation between space exploration and mining in this region is also historical. The establishment of the Swedish launch site in the 1960s drew on an already-existing scientific infrastructure whose purpose was atmospheric research and space physics. The development of this scientific infrastructure, in turn, was enabled by an earlier infrastructure that was built for underground resource extraction. This mining infrastructure has a history that stretches back to 17th-century copper and silver mines but most significantly to the late-19th-century establishment of the Kiruna mine, one of the world’s largest underground iron ore mines. It was to a great extent that the existence of what is essentially the mine’s surrounding infrastructure motivated the placement of the rocket base in this particular region.

While local politicians and space actors have long attempted to brand Kiruna as a “space town” (Backman 2015), this history reveals the processes that have made such branding and associated space activities possible to begin with.

By the same token, the vertical territorial understanding (Braun 2000) reflected by ongoing developments around space exploration relies on assumptions about “emptiness” conjured up by the mining industry. Today, such understandings are invoked to render resourceful not only horizontal space and the underground, but likewise vertical space as it extends upwards. Alongside tropes about empty landscapes, the branding of Kiruna as a globally attractive space hub is frequently made with reference to its vast and supposedly unpopulated surroundings as well as its relatively unoccupied airspace.

In the 1959 Swedish-American science fiction film Space Invasion of Lapland (Rymdinvasion i Lappland), two scientists travel to northern Sweden upon hearing about the landing of a mysterious extraterrestrial object.[1] As viewers, we have already had a glimpse of the latter: the film opens with Sámi reindeer herders awing at the glowing round object as it glides over the subarctic landscape, before finally crashing into a snow-covered mountain. The movement of the presumed meteorite strikes us as eerie and not at all in accordance with the way an actual space rock would behave upon entering into the atmosphere. As the story continues, we gradually come to learn that the puzzle that the travelers have been called upon to unravel ultimately exceeds the grasp of modern science, as the object turns out to be an alien spaceship.

A conversation unfolds between the two scientists onboard a plane bound for Kiruna. Nodding at a boat visible from the plane’s window, the famous geologist, Dr. Wilson, asks his fellow traveler, Dr. Engström, whether he knows what it is. “Ore boats from the Kiruna ore mines, the richest iron deposit in the world,” Dr. Engström replies, upon which Dr. Wilson speculates: “[D]o you think that the magnetic attraction of the mines could have any bearing on the meteor falling there?” His colleague is skeptical, replying, “Come on doctor, like making the meteor skid across the snow for miles?” A brief moment of deliberation follows, before Dr. Wilson finally asks: “Who said it had to be a meteor?”

The speculative relation drawn by Dr. Wilson between the extraterrestrial and the Kiruna mine compels me to also attend to another set of connections drawn by some of my interlocutors. While Redfield’s question about the coincidence of seemingly unrelated phenomena in French Guiana has oriented my attention to infrastructural history, here I would like to return to the relations that my interlocutors themselves drew between things.

A PhD student at the local space campus offered a captivating analogy. Sitting in his office, we were chatting away about everything from aurora borealis and housing in Kiruna to the navigation and control of small satellites for deep space exploration, which was the subject of his doctoral studies. As the conversation went on, he told me that he did not really believe in space colonization in the way this is usually imagined. He did not think that space settlements would emerge as ends in themselves but rather as consequences of off-Earth mining. He brought home this point by way of comparison, suggesting that this is not very different from the way Kiruna did not exist prior to the establishment of the local mine. According to him, there could be no significant reason to settle down in the region prior to the emergence of a mining infrastructure.

Akin to Dr. Wilson’s speculation about the connection between the extraplanetary and the local iron ore mine, my interlocutors, too, made connections, contrasts, and analogies between mining and outer space. At times, the Kiruna mine served as a “technology of the imagination” (Sneath, Holbraad, and Pedersen 2009) or speculative device for envisaging the specific unfoldings of a future beyond Earth.

The city and the mine. Photo by the author.

Scholars have argued that remote sensing technology has served to create and reconfigure environments on Earth, often unintentionally (Sörlin and Wormbs 2018). By affording a view from above and without, satellites have participated in the modification of our ways of conceptualizing and relating to our earthly and atmospheric surrounds. In this blog post, I have tried to highlight a somewhat different matter – namely, how grounded, planetary milieus become infrastructures for envisioning space. These are “the terrestrial localit[ies] of outer space” (Messeri 2016: 163); places and relations – in this case the infrastructural history of a mining town – that reshape landscapes in an immediately material way and occasionally come to inform situated, extraplanetary imaginaries.

[1] The regional designation in the title of this film draws on the discriminatory expression “lapp,” a Swedish term that has been used historically to label the Sámi. This term does not exist in the Sámi languages. In Northern Sámi, this region is known as Sápmi.

I would like to thank Platypus’s contributing editors Kim Fernandes and Yakup Deniz Kahraman for their thoughtful suggestions and comments. This research received funding from the National Science Center, Poland, project number 2020/38/E/HS3/00241.

Backman, Fredrick. 2015. Making place for space: A history of “space town” Kiruna 1943-2000. Umeå: Umeå University.

Braun, Bruce. 2000. “Producing vertical territory: Geology and governmentality in late Victorian Canada.” Cultural Geographies 7 (1): 7-46.

McCormack, Derek P. 2018. Atmospheric things: On the allure of elemental envelopment. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Messeri, Lisa. 2016. Placing outer space: An earthly ethnography of other worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ojani, Chakad. 2022. “Speculative relations in Lima: Encounters with the limits of fog capture and ethnography.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 12 (2): 468-481.

Park, William. 2016. “Why caves are the best place to train astronauts”. BBC, November 30. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20161130-why-caves-are-the-best-place-to-train-astronauts (accessed 5/11/2022).

Redfield, Peter. 2000. Space in the tropics: From convicts to rockets in French Guiana. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sneath, David, Martin Holbraad, and Morten Axel Pedersen. 2009. “Technologies of the imagination: An introduction.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 74 (1): 5-30.

Sörlin, Sverker, and Nina Wormbs. 2018. “Environing technologies: A theory of making environment.” History and Technology 34 (2): 101-125.

Danny Kingsley suggests that research integrity begins with the training researchers receive at university. Achieving Open Research and increasing reproducibility requires systematic research training that focuses specifically on research practice.

The post Guest Post: Start at the Beginning – The Need for ‘Research Practice’ Training appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

This is is a multilingual comic that serves as a meditation on the infrastructures of COVID-19, care, and time. In the spirit of the multilingual spaces I inhabit in Tio’tia:ke/Mooninyaang/Montréal, I have chosen to write bilingually—a process that can be messy, but that speaks to my experiences of COVID-19 locally as I am thinking of COVID-19 globally.

This refusal to separate my experiences into two linguistic boxes is an experiment in thinking about both the process and products of creation through the form of comics, an art form popular in Québec, where I lived during the start of the pandemic (and still live, at the time of this writing).

A note on translation: In panel 6, I have used “vie valide” (FR) as “abled life” (EN). This is meant to emphasize the language in the source material, which emphasizes both hypocrisy and violence of ableist and eugenicist approaches to a pandemic, and also serves as a power of refusal. As someone who is disabled but who is not francophone, I welcome conversations about this language over Twitter or over email (see profile).

Il s’agit d’une bande dessinée multilingue qui sert de méditation sur les infrastructures de COVID-19, les soins et le temps. Dans l’esprit des espaces multilingues que j’habite à Tio’tia:ke/Mooninyaang/Montréal, j’ai choisi d’écrire de manière bilingue – un processus qui peut être quelque peu compliqué, mais qui parle de mes expériences de COVID-19 au niveau local tout en pensant à COVID-19 au niveau mondial.

Ce refus de séparer mes expériences en deux boîtes linguistiques est une expérience de réflexion sur le processus et les produits de la création, en utilisant la forme de la bande dessinée, une forme d’art populaire au Québec, où je vivais au début de la pandémie (et où je vis toujours, au moment d’écrire ces lignes).

Une note sur la traduction : Dans le panneau 6, j’ai utilisé “vie valide” (FR) comme “abled life” (EN). Ceci a pour but de mettre l’accent sur le langage du matériel source, qui souligne à la fois l’hypocrisie et la violence des approches “ableistes” et eugénistes d’une pandémie, et sert également de pouvoir de refus. En tant que personne handicapée mais non francophone, je suis heureux de discuter de ce langage sur Twitter ou par e-mail (voir profil).

(note: the comic uses a dark brown, light brown, and blue color palette and appears to be drawn on a textured background)

(note : la bande dessinée utilise une palette de couleurs marron foncé, marron clair et bleu et semble être dessinée sur un arrière-plan texturé)

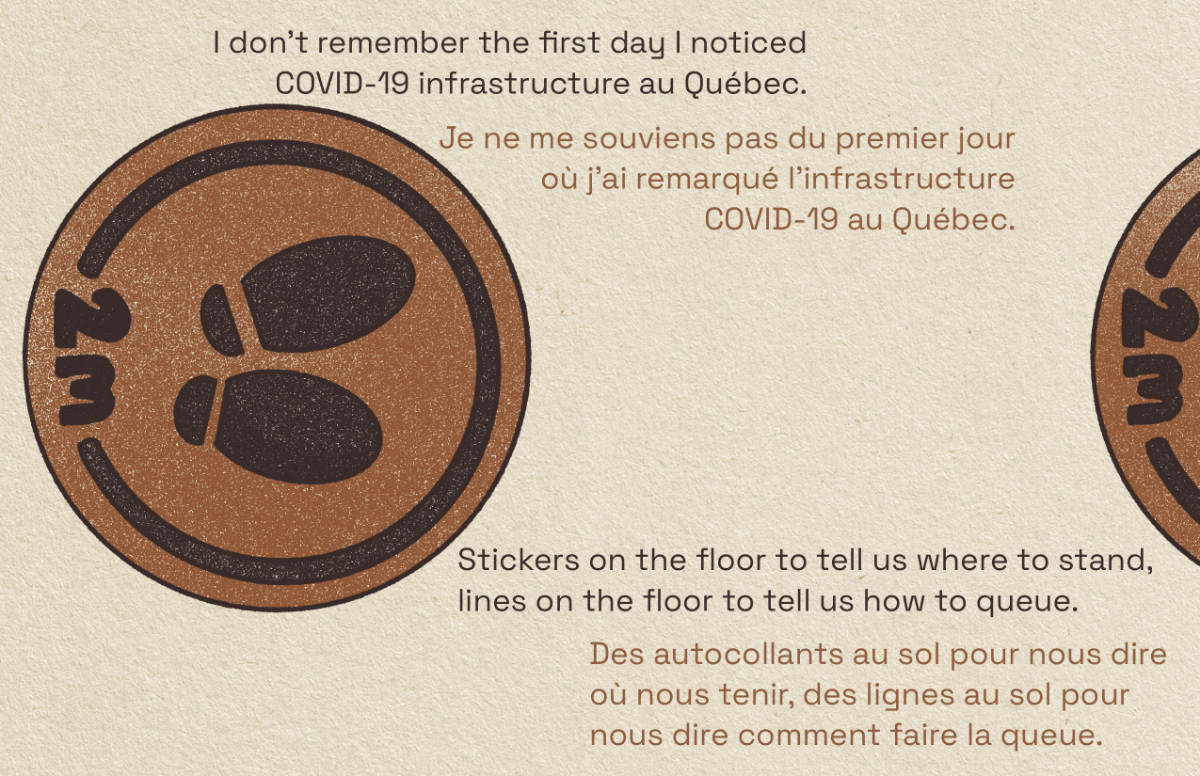

Panel 1: A comic spread with text that reads/Une bande dessinée avec un texte qui dit: “I don’t remember the first day I noticed COVID-19 infrastructure in Québec .” “Je ne me souviens pas du premier jour où j’ai remarqué l’infrastructure COVID-19 au Québec.”

“Stickers on the floor to tell us where to stand, lines on the floor to tell us how to queue.” “Des autocollants au sol pour nous dire où nous tenir, des lignes au sol pour nous dire comment faire la queue.”

In the background, there is a light and dark brown illustration of two stickers with footprints and “2m” written on them. / En arrière-plan, il y a une illustration marron clair et marron foncé de deux autocollants avec des empreintes de pieds et “2m” écrit dessus.

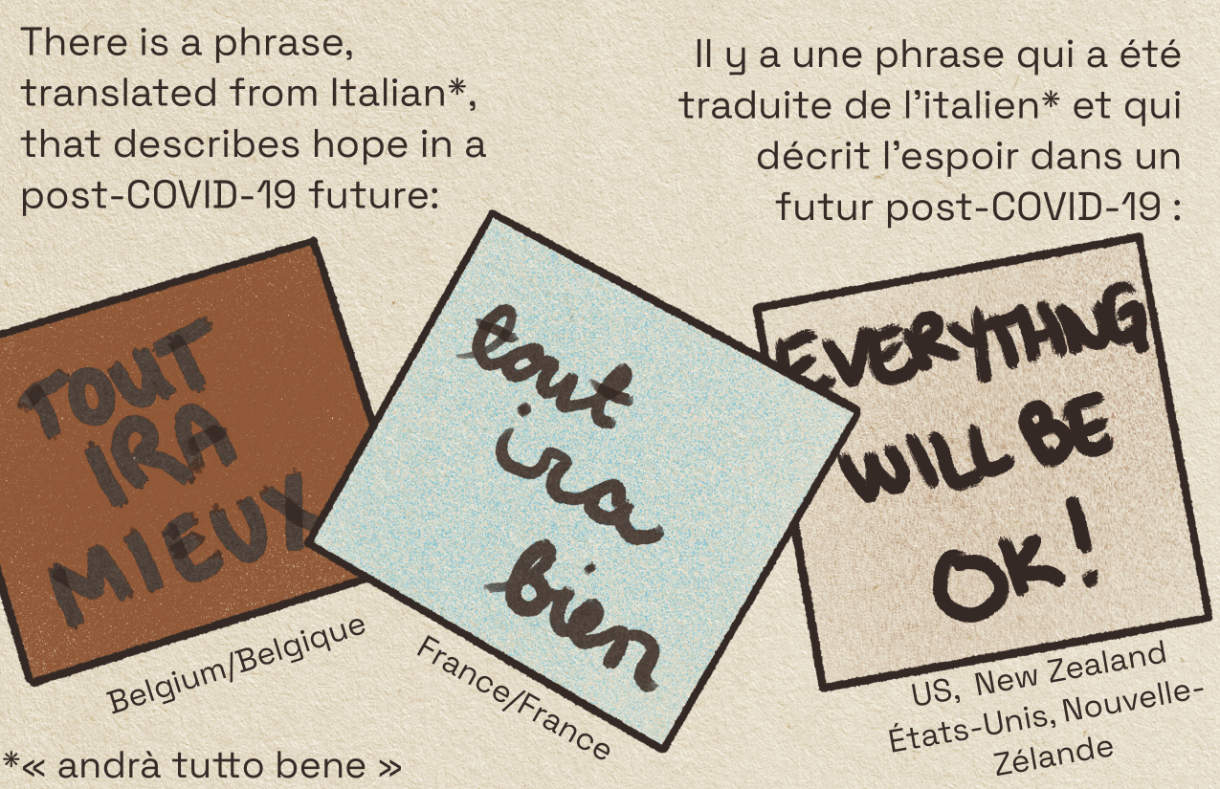

Panel 2: The text reads/Un texte qui dit: “There is a phrase, translated from Italian*, that describes hope in a post-COVID-19 future:” “Il y a une phrase qui a été traduite de l’italien* et qui décrit l’espoir dans un futur post-COVID-19 :”

Below, there are signs that read / En dessous, il y a des panneaux qui disent: “Tout ira mieux” (Belgium/Belgique), “tout ira bien” (France/France), “Everything will be OK!” (US, New Zealand, États-Unis, Nouvelle Zélande)

“*« andrà tutto bene »”

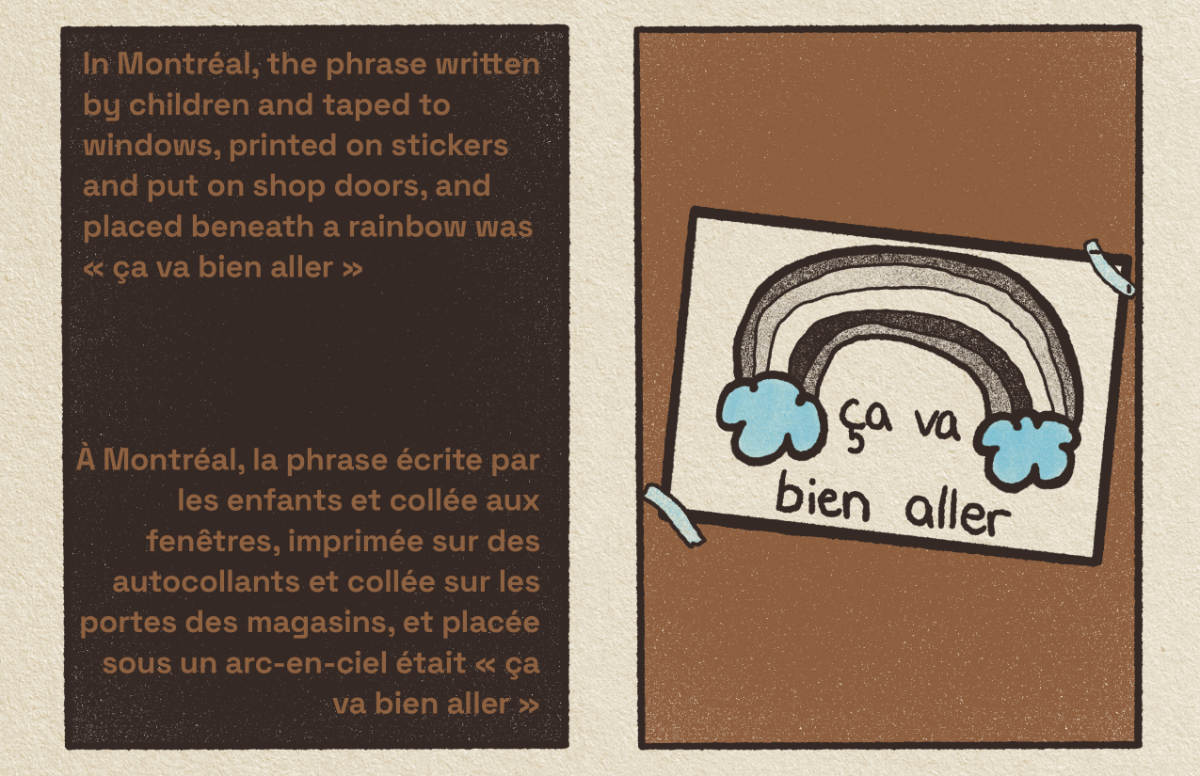

Panel 3: The text reads / Un texte qui dit: “In Montréal, the phrase written by children and taped to windows, printed on stickers and put on shop doors, and placed beneath a rainbow was « ça va bien aller »”

“À Montréal, la phrase écrite par les enfants et collée aux fenêtres, imprimée sur des autocollants et collée sur les portes des magasins, et placée sous un arc-en-ciel était « ça va bien aller »”

In the frame next to it is a drawing of a rainbow in brown, white, and blue, taped to something. It reads ça va bien aller. / Dans le cadre à côté, il y a un dessin d’un arc-en-ciel en marron, blanc et bleu, collé à quelque chose. On peut lire “ça va bien aller”.

Panel 4: The text reads / Un texte qui dit: “People with different kinds of relationships to labour, different identities, and different incomes have had different experiences under COVID-19 (and capitalism). Race, immigration status, class, and more shape how COVID-19 has been felt by people around the world.”

“Des personnes ayant des relations différentes avec le travail, des identités differentes et des revenus différents ont vecu des expériences différentes dans le cadre de COVID-19 (et du capitalisme).”

“La race, le statut au regard de la législation sur l’immigration, la classe sociale et d’autres factures façonnent la manière dont le COVID-19 a étè ressenti par les gens du monde entier.”

Next to the text is an image of a healthcare worker (who appears to be not white) in blue, wearing gloves, wearing a mask, and with hair tied up. À côté du texte se trouve l’image d’un.e travailleur.se de la santé (qui semble ne pas être blanc.he) en bleu, portant des gants, un masque et les cheveux attachés.

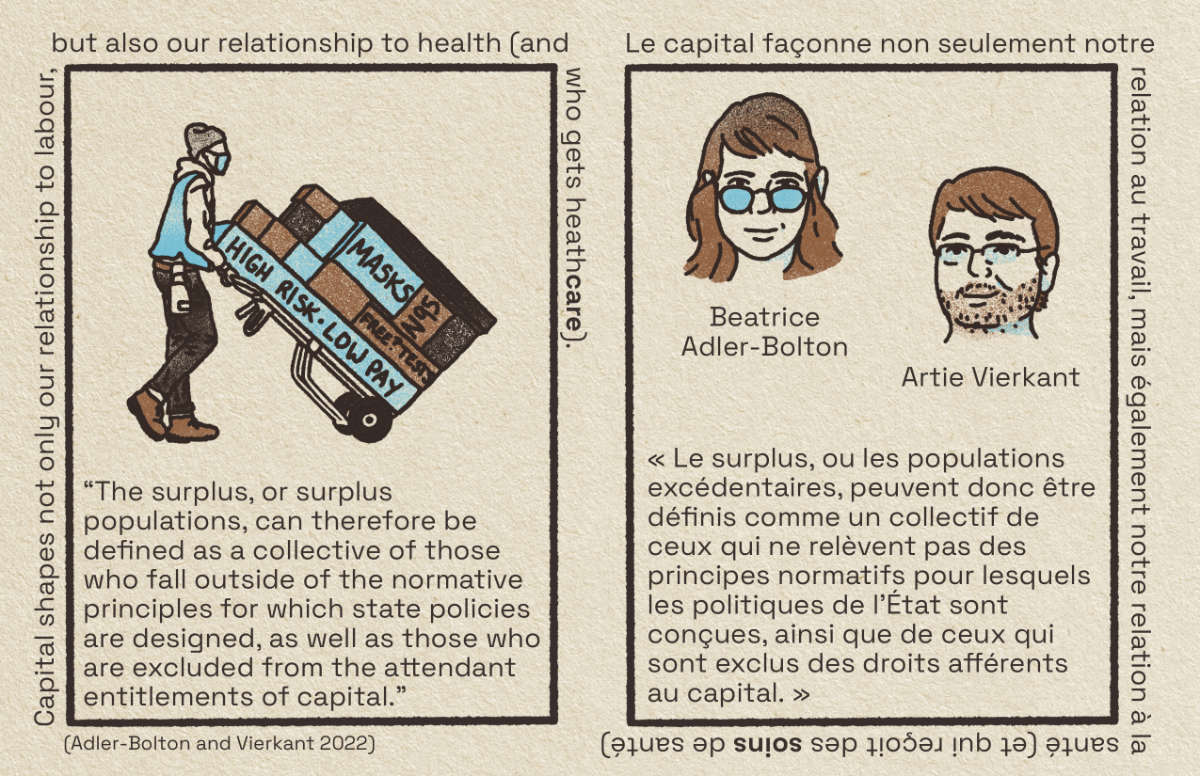

Panel 5: There are two panels, with text around them and images inside. Il y a deux panneaux, avec du texte autour et des images à l’intérieur.

On the left, the text around the panel reads / À gauche, le texte autour du panneau dit: “Capital shapes not only our relationship to labour, but also our relationship to health (and who gets heathcare).”

On the right, the text around the panel reads / À droit, le texte autour du panneau dit: “Le capital façonne non seulement notre rélatuion au travail, mais également notre relation à la santé (et qui reçoit des soins de santé)” Under, it reads: (Adler-Bolton and Vierkant 2022)

On the left, there is a drawing of a white deliveryperson who is pushing a trolley with a number of packages on it, including / À gauche, le dessin d’un livreur blanc qui pousse un chariot sur lequel se trouvent plusieurs colis, dont “HIGH RISK LOW PAY,” “MASKS,” “N95,” “FREE? TESTS.” Below, it reads / En dessous, on peut lire: “The surplus, or surplus populations, can therefore be defined as a collective of those who fall outside of the normative principles for which state policies are designed, as well as those who are excluded from the attendant entitlements of capital.”

On the right, there is a drawing of two white people. The person on the left is white, has shoulder-length hair, is wearing glasses, and is named as “Beatrice Adler-Bolton.” The person on the right is white, is wearing less tinted glasses, has a beard, and short hair, and is named as “Artie Vierkant.” / À droite, il y a le dessin de deux personnes blanches. La personne de gauche est blanche, a les cheveux longs, porte des lunettes et s’appelle “Beatrice Adler-Bolton”. La personne à droite est blanche, porte des lunettes moins teintées, a une barbe et des cheveux courts, et s’appelle “Artie Vierkant”.

Below, it reads / En dessous, on peut lire: “Le surplus, ou les populations excédentaires, peuvent donc être définis comme un collectif de ceux ne relèvent pas des principes normatifs pour lesquels les politiques de l’État sont conçues, ainsi que de ceux qui sont exclus des droits afférents au capital.”

Panel 6: There are two panels, with text around both. On the left, it reads / Il y a deux panneaux, avec du texte autour des deux. À gauche, on peut lire: “Disability justice organizer Mia Mingus reminds us that political refusals cost disabled lives.” Inside the square is a skeleton in brown ground, with some grass. A l’intérieur du panneau se trouve un squelette dans un sol brun, avec un peu d’herbe.

Inside the right panel, the text reads / À l’intérieur du panneau droit, le texte dit: “We will not trade disabled deaths for abled life. We will not allow disabled people to be disposable or the necessary collateral damage for the status quo.” “Nous n’échangerons pas les décès d’handicapés contre une vie valide.” The right panel has a drawing of an IV hanger. Le panneau de droite présente le dessin d’un support de perfusion.

Panel 7: A spread with three panels. Two on either side have drawings of masks on the ground, with leaves and dirt. Below the left, it reads, “Que se passe-t-il lorsque les infrastructures de soins collectifs son mises au rebut, jetées au nom du “choix” individuel ?” / Une page avec trois panneaux. Deux de chaque côté ont des dessins de masques sur le sol, avec des feuilles et de la terre. En bas à gauche, on peut lire, “Que se passe-t-il lorsque les infrastructures de soins collectifs son mises au rebut, jetées au nom du “choix” individuel ?”

In the middle panel, the text reads / Dans le panneau du milieu, le texte se lit comme suit: “We will not look away from the mass illness and death that surrounds us or from a state machine that is more committed to churning out profit and privileged comfort with eugenic abandonment.” “Nous ne détournerons pas les yeux de la maladie et de la morte de masse qui nous entournent ou d’une machine d’État qui east plus déterminée à générer des profits et un confort privilégié avec un abandon eugénique.”

On the right, it reads / À droit, le texte dit: “What happens when collective care infrastructures are discarded, thrown away in the name of individual “choice”?”

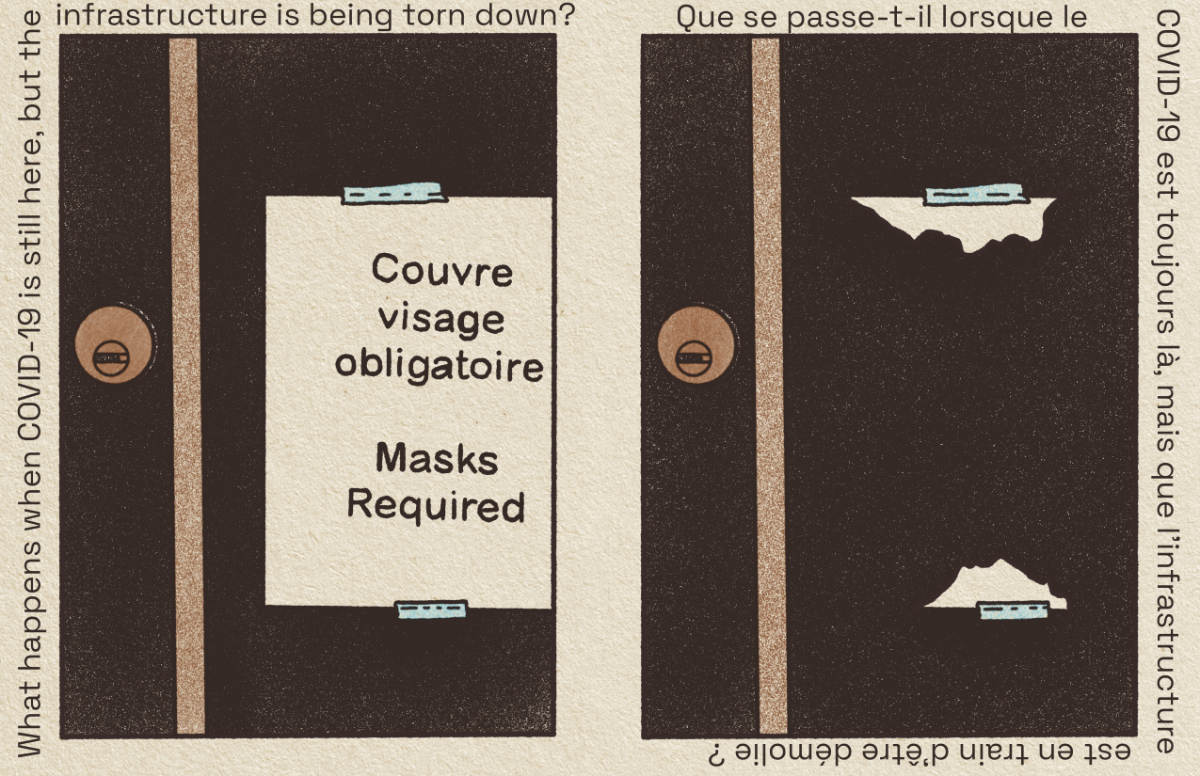

Panel 8: A spread of two panels. On the left, around the panel, the text reads, “What happens when COVID-19 is still here, but the infrastructure is being torn down?” Inside, is a drawing of a sign that reads “Couvre visage obligatoire / Masks required” taped to a door. / Deux panneaux. À gauche, autour du panneau, le texte a dit : “What happens when COVID-19 is still here, but the infrastructure is being torn down?” À l’intérieur, le dessin d’un panneau indiquant “Couvre visage obligatoire / Masks required” collé sur une porte.

On the right, around the panel, it reads / A droite, autour du panneau, le texte a dit: “Que se passe-t-il lorsque le COVID1-9 est toujours là, mais que l’infrastructure est en train d’être démolie ?” Inside the panel is a drawing of the tape on the door with part of the sign still remaining, but most is missing. / À l’intérieur du panneau se trouve un dessin du ruban adhésif sur la porte. Il reste une partie du panneau, mais la majeure partie est manquante.

Panel 9: Two panels. On the left, it reads (Silverstein and Lincoln 2022). / Deux panneaux. À gauche, on peut lire (Silverstein et Lincoln 2022).

On the left around the panel, it reads / À gauche, autour du panneau, on peut lire: “Broken pandemic infrastructures were not the “ça va” many of us hoped for.” Inside the panel, it reads / À l’intérieur du panneau, le texte dit : “How did the united States end up desensitized to mass death and disability, angrily opposed to almost all means of mitigating an occasionally fatal airborne virus, and willing to accept so little from the powerful?” “Comment les États-Unis ont-ils fini par êtr désensibilisés à la mort et à l’incapacité de masse, opposés avec colère à presque tous les moyens d’atténuer un virus aérien parfois mortel, et prêts à accepter si peu des puissants?”

Around the right panel, it says / Autour du panneau de droite, le texte a dit: “Infrastructures pandémiques brisées n’ont pas été les “ça va” que beaucoup d’entre nous avaient éspérées.” Inside the panel is a drawing of two people. On the left, is a drawing of a white person with glasses and brown hair, who is named Martha Lincoln. Below, is a drawing of a white person with brown hair and a beard named Jason Silverstein. / À l’intérieur du panneau se trouve le dessin de deux personnes. À gauche, le dessin d’une personne blanche avec des lunettes et des cheveux bruns, qui s’appelle Martha Lincoln. En dessous, se trouve le dessin d’une personne blanche aux cheveux bruns et à la barbe, nommée Jason Silverstein.

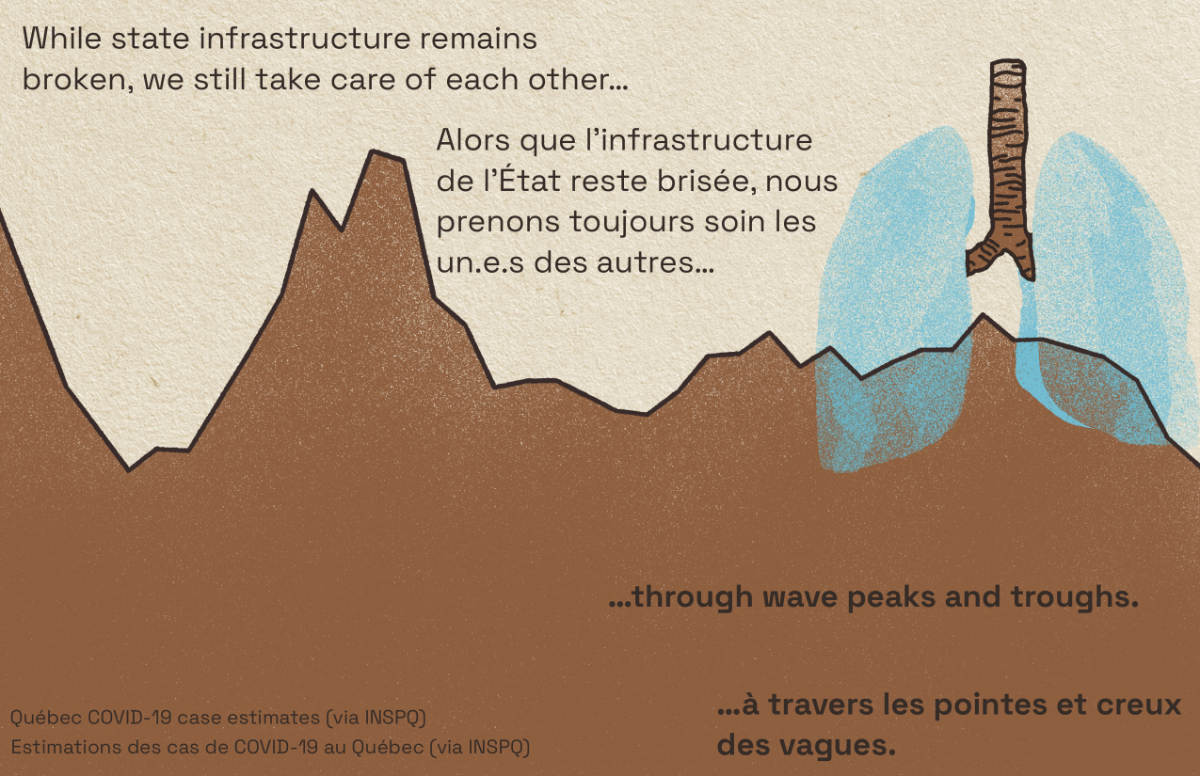

Panel 10: A panel spread that has a drawing of COVID-19 case estimates in brown (data via INSPQ), and a drawing of a lung with a brown trachea with blue lungs. Un panneau avec un dessin des estimations de cas COVID-19 en brun (données via INSPQ), et un dessin d’un poumon avec une trachée brune avec des poumons bleus.

The text reads / Le texte dit: “While state infrastructure remains broken, we still take care of each other…” “Alors que l’infrastructure de l’État reste brisée, nous prenons toujours soin les un.e.s des autres…”

Below, it reads / En dessous, le texte dit: “…through wave peaks and troughs.” “…à travers les pointes et creux des vagues.”

Panel 11: Two panels. / Deux panneaux.

On the left, around the box, it reads / À gauche, autour de la boîte, le texte dit: “We are not singular beings: we are social animals, and we depend on each other.” Inside (in light brown text on dark brown), it reads / À l’intérieur (en texte brun clair sur brun foncé), le texte a dit: “Interdependence acknowledges that our survival is bound up together, that we are interconnected and what you do impacts others. If this pandemic has done nothing else, it has illuminated how horrible our society is at valuing and practicing interdependence. Interdependence is the only way out of most of the most pressing issues we face today.” (Mingus 2022) is on the left / est à gauche.

Around the right panel it reads / Autour du panneau de droite, le texte a dit: “Nous ne sommes pas des êtres singuliers: nous sommes des animaux sociaux, et nous dépendons les un.e.s des autres.” Inside, it reads (in dark brown text on light brown) “L’interdépendance reconnaît que notre survie est liée, que nous sommes interconnectés et que ce que vous faites a un impact sur les autres. Si cette pandémie n’a rien fait d’autre, elle a mis en lumière à quel point notre société est horrible à valoriser et à pratiquer l’interdépendance. L’interdépendance est le seul moyen de sortir de la plupart des problèmes les plus urgents auxquels nous sommes confrontés aujourd’hui.”

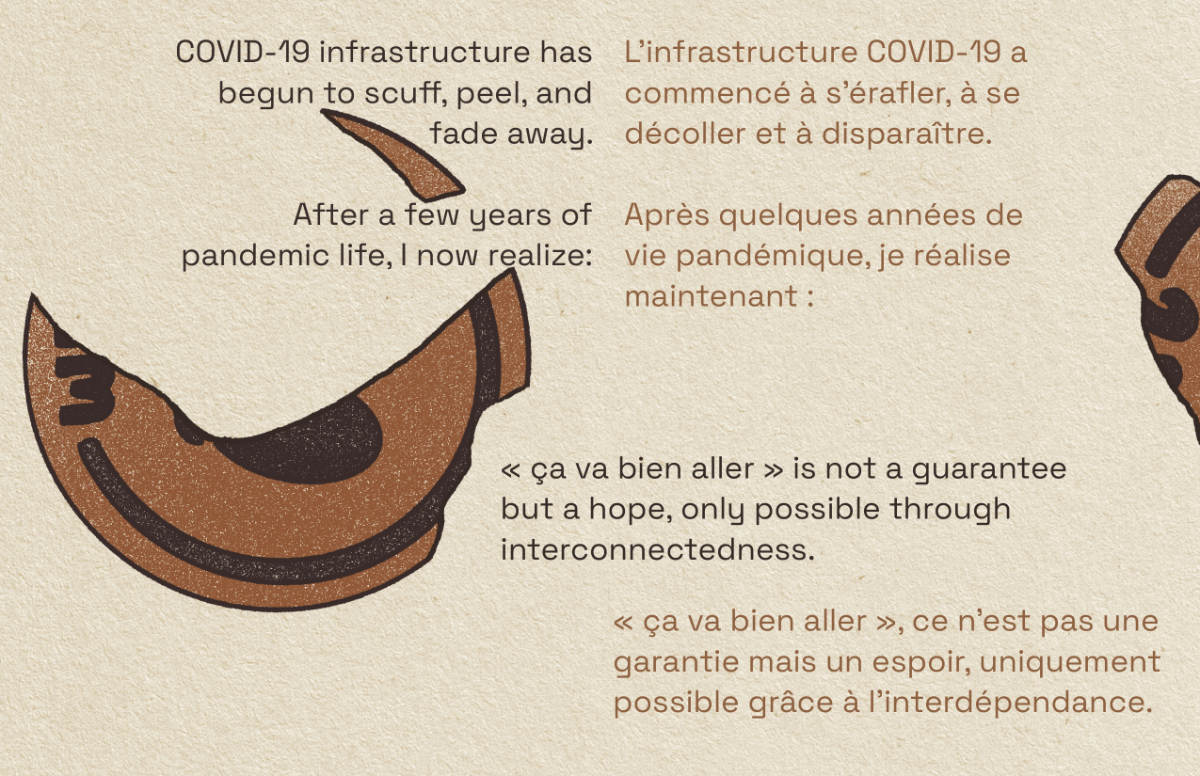

Panel 12: A spread with text and images of the first panel’s stickers of feet and “2m,” but it is largely missing. Un panneau avec le texte et les images des autocollants de pieds et de “2m” du premier panneau, mais il est en grande partie absent.

The text reads / Le texte a dit: “COVID-19 infrastructure has begun to scuff, peel, and fade away. After a few years of pandemic life, I now realize: ” “L’infrastructure COVID-19 a commencé à s’érafler, às se décoller et à disparaître. Après quelques années de vie pandémique, je réalise maintenant :” “« ça va bien aller » is not a guarantee but a hope, only possible through interconnectedness.” “« ça va bien aller », ce n’est pas une garantie mais un espoir, uniquement possible grâce à l’interdépendance.”

Adler-Bolton, Beatrice, and Artie Vierkant. 2022. Health Communism: A Surplus Manifesto. Verso Books.

Institute national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ). n.d. “Données COVID-19 au Québec.” INSPQ: Centre d’expertise et de référence en santé publique. Accessed February 05, 2023. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees.

Mingus, Mia. 2022. “You Are Not Entitled To Our Deaths: COVID, Abled Supremacy & Interdependence.” Blog. Leaving Evidence (blog). January 16, 2022. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2022/01/16/you-are-not-entitled-to-our-deaths-covid-abled-supremacy-interdependence/.

Silverstein, Jason, and Martha Lincoln. 2022. “Why We Fight.” Blog. Peste (blog). December 13, 2022. https://www.pestemag.com/first-row/why-we-fight-w55lm.

A compilation of links and a video to incisive analyses of ChatGPT and what it means for the future.

The post Thinking About ChatGPT and the Future — Where Are We On AI’s Development Curve? appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Mark Huskisson looks at the open source tools enabling a world of scholarly communication that is more broadly global, diverse, and inclusive than is perhaps recognized.

The post Guest Post – Scholarly Publishing as a Global Endeavor: Leveraging Open Source Software for Bibliodiversity appeared first on The Scholarly Kitchen.

“Burnout” is an inescapable concept these days. Its current usage, however, is a far cry from its origins in one psychologist’s appropriation of the imagery of urban arson in the 1970s, much of it instigated by landlords looking for insurance payouts. Bench Ansfield, a historian, makes the case for recognizing and reclaiming burnout’s roots as a necessary social project:

Unlike broken windows, burnout has shed its roots in the social scientific vision of urban crisis: We don’t tend to associate the term with the city and its tumultuous history. But it’s actually quite telling that Freudenberger saw himself and his burned-out coworkers as akin to burned-out buildings. Though he didn’t acknowledge it in his own exploration of the term, those torched buildings had generated value by being destroyed. In transposing the city’s creative destruction onto the bodies and minds of the urban care workers who were attending to its plight, Freudenberger’s burnout likewise telegraphed how depletion, even to the point of destruction, could be profitable. After all, Freudenberger and his coworkers at the free clinic were struggling to patch the many holes of a healthcare system that valued profit above access.

Many left critics of the burnout paradigm have faulted the concept for individualizing and naturalizing the large-scale social antagonisms of neoliberal times. “Anytime you wanna use the word burnout replace it with trauma and exploitation,” reads one representative tweet from the Nap Ministry, a project that advocates rest as a form of resistance. They’re not wrong. In Freudenberger’s chapter on preventing burnout, for instance, he exhorts us to “acknowledge that the world is the way it is” and warns, “We can’t despair over it, dwell on the pity of it, or agitate about it.” That’s psychobabble for Margaret Thatcher’s infamous slogan, “There is no alternative.” But if we excavate burnout’s infrastructural unconscious—its origins in the material conditions of conflagration—we might discover a term with an unlikely potential for subversive meaning. An artifact of an incendiary history, burnout can vividly name the disposability of targeted populations under racial capitalism—a dynamic that, over time, has ensnared ever-wider swaths of the workforce.