Being responsible for ourselves, knowing our own wants and meeting them, is difficult enough — so difficult that the notion of being responsible for anyone else, knowing anyone else’s innermost desires and slaking them, seems like a superhuman feat. And yet the entire history of our species rests upon it — the scores of generations of parents who, despite the near-impossibility of getting it right, have raised small defenseless creatures into a capable continuation of the species. This recognition is precisely what made Donald Winnicott’s notion of good-enough parenting so revolutionary and so liberating, and what Florida Scott Maxwell held in mind when she considered the most important thing to remember about your mother.

And yet to be a parent is to suffer the ceaseless anxiety of getting it wrong.

A touching antidote to that anxiety comes from Fred Rogers (March 20, 1928–February 27, 2003) in Dear Mister Rogers, Does It Ever Rain in Your Neighborhood? (public library) — the collection of his letters to and from parents and children.

Writing back to a young father-to-be riven by anxiety about the task before him, Mister Rogers offers:

Parenthood is not learned: Parenthood is an inner change. Being a parent is a complex thing. It involves not only trying to feel what our children are feeling, but also trying to understand our own needs and feelings that our children evoke. That’s why I have always said that parenthood gives us another chance to grow.

In a sentiment that applies as much to parenting as it does to any love relationship — one evocative of Iris Murdoch’s superb definition of love as “the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real” — he adds:

There is one universal need we all share: We all long to be cared for, and that longing lies at the root of our ability to care for our children. If the day ever came when we were able to accept ourselves and our children exactly as we and they are, then I believe we would have come very close to an ultimate understanding of what “good” parenting means. It’s part of being human to fall short of that total acceptance and ultimate understanding — and often far short. But the most important gifts a parent can give a child are the gifts of our unconditional love and our respect for that child’s uniqueness.

With the mighty touch of assurance that is personal experience, he reflects:

Looking back over the years of parenting that my wife and I have had with our two boys, I feel good about who we are and what we’ve done. I don’t mean we were perfect parents. Not at all. Our years with our children were marked by plenty of inappropriate responses. Both Joanne and I can recall many times when we wish we’d said or done something different. But we didn’t, and we’ve learned not to feel too guilty about that. What gives us our good feelings about our parenting is that we always cared and always tried to do our best.

Couple with Kahlil Gibran’s timeless advice on parenting, then revisit the young single mother Susan Sontag’s 10 rules for raising a child.

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Beaumarchais and <em>Electronic Enlightenment</em>

The addition to Electronic Enlightenment (EE) of nearly 500 letters from the Beaumarchais correspondence is a significant event in eighteenth-century studies. Drawn from the second volume of Gunnar and Mavis von Proschwitz’s edited collection, Beaumarchais and the “Courrier de lÉurope”, first published thirty years ago in Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, these letters join with 175 letters from the first volume (previously included in EE). The total of 660 letters in this collection include a combination of letters printed in that periodical and letters from public and private collections. (In 2005, von Proschwitz published a selection of 107 of these in a French edition, entitled Lettres de Combat.)

Collectively the letters being published by EE represent the largest tranche of Beaumarchais letters available for online research; moreover, they constitute approximately one third of Beaumarchais letters published to date and over one sixth of all known Beaumarchais letters in existence.

In the context of eighteenth-century correspondences, the Beaumarchais archive stands out for several reasons. The first is the volume of the archive. The known portion of the Beaumarchais papers is over 4,500 documents, constituting one of the largest corpora of eighteenth-century papers known. The full archive, if ever fully inventoried and edited, would run somewhere between 6,000 and 20,000 documents. At the upper range it would become among the largest known archives of personal papers of the period.

The second is geographical breadth—from Vienna to Madrid to the Netherlands to England and North America, the Beaumarchais correspondence is important because it shows how actually we limit our understanding if we focus on solely “French” or “Francophone” correspondence networks.

The third is sociological breadth—Beaumarchais as an historical figure offers us insights into the eighteenth century that stand apart from the major figures whose correspondence has been edited and studied. He was an artisan, a musician, a financier, commercial entrepreneur, printer, investor, politician, judge, diplomat, spy, litigant, criminal (he was imprisoned in at least four capitals), husband, lover, brother, father and, of course, a playwright. His correspondence, and thus the network of correspondents connected him to a wider swath of eighteenth-century European and North American society than almost all personal correspondences studied to date, rivaling and perhaps exceeding the Franklin and Jefferson papers in this respect.

The editorial history of the Beaumarchais correspondence extends over two centuries of literary and political history. Since 1809, when the first edition of Beaumarchais’s Oeuvres was published, over 1,500 letters have been edited—though most of them not with the critical apparatus of the Proschwitz letters published by EE—over the course of more than two centuries.

Nearly 500 letters were printed in partial editions of Beamarchais’ work or correspondence, from 1809 to 1929. The first edition of his complete works edited by his amanuensis, Gudin de la Brenellerie (seven volumes, 1809), included 55 letters that Gudin had transcribed. A second edition, by the journalist, historian and politician Saint-Marc de Girardin in 1837 included 53 additional letters. A collection of 29 letters from the Comedie Francaise archives were published in the Revue Retrospective (1836). In his two-volume biography, Beaumarchais et son temps (1858), Louis de Loménie, referenced and included partial transcripts of hundreds of letters, but included in the appendix only 35 complete texts of previously unedited letters. A second biographer, Eugène Lentilhac, in his Beaumarchais et ses oeuvres (1887), included 12 partially transcribed letters not previously published. In 1890, Louis Bonneville de Marsagny published a biography of Beaumarchais’s third (and longest lasting) wife, Marie Thérèse Willermalauz, and claimed to have consulted “sa correspondance inédite” though no letters are reproduced or directly referenced.

In the early twentieth century, the first effort to produce a complete edition of the correspondence was made by Louis Thomas; however, as he explains in the preface to his edition entitled Lettres de Jeunesse (1923), his military service during the Great War put an end to his research; so in 1923 he published 167 letters from the first two decades of Beaumarchais’ adult life, some of which had been previously published. Several years later, in 1929, the eminent French literature scholar in the United States of the day, Gilbert Chinard, edited a collection of Lettres inédites de Beaumarchais consisting of 109 letters acquired by the Clements Library at the University of Michigan; these consisted of letters to his wife and daughter.

In more recent decades, over 1,000 additional items have been published, between the edition launched by Brian Morton in 1968, continued by Donald Spinelli, which added an additional 300 previously unpublished letters over four volumes of Correspondence, and then in 1990, the Proschwitz edition.

Proschwitz, a noted philologist, added to these letters the most extensive critical apparatus associated with any edition of Beaumarchais letters. He did not seek to produce a critical edition or a material bibliography of these letters, approaches that are difficult to apply to eighteenth-century correspondence in general and to the Beaumarchais archive in particular. Rather, Proschwitz in his notes emphasized the significance of these documents for our understanding of Beaumarcahis’ life and of the eighteenth century. In these letters, we see Beaumarchais not only as a playwright seeking to circumvent censorship to have Marriage de Figaro finally staged, but also as an entrepreneur, a printer, an urban property owner, an emissary, and a transatlantic merchant. Through this window we have a window on the eighteenth century that is geographically, socially, and culturally much broader and more diverse than what we generally encounter through the correspondences previously published in EE.

With the appearance of these letters and the launching of the first new projects on Beaumarchais’s correspondence in 50 years, including the effort spearheaded by Linda Gil to produce a definitive inventory with a material bibliography, and my own work to analyze the network of correspondents from the known correspondence, this publication in EE offers eighteenth-century scholars new reason to consider a longstanding, but still little understood, figure of the age.

A version of this blog post was first published on Electronic Enlightenment.

Featured image by Debby Hudson on Unsplash (public domain)

Attacks against Trans women are attacks against the women’s movement and the fight for better equality and justice.#TransDayOfVisibility #TransRightsAreHumanRights

Read the full story by https://t.co/ZIUBAuI38Q‘s founding publisher, Judy Rebick: https://t.co/G8o62tC3Zo

— rabble.ca (@rabbleca) March 31, 2023

Last week, longtime Canadian feminist and leftist, Judy Rebick, published a piece at rabble.ca, the site she founded, entitled “My feminism is Trans inclusive.” It in, Rebick explains that she has never written on trans issues before, but having been accused of being a “TERF” (trans-exclusionary radical feminist), she wished to reject the label, and offered an apology of sorts for having testified in support of Vancouver Rape Relief (VRR), who were forced into a human rights case brought against the transition house and rape crisis line by Kimberly Nixon in 1995. Nixon had been rejected from a training group with the collective on account of having been born a man, and on account of the fact the transition house and collective was women-only. Under apparent pressure from her leftist comrades, Rebick explained, in her recent piece, that she “didn’t really understand the issues involved,” that she had “believed that gender was socially constructed,” but was “ignorant,” and has since learned and changed her position. Rebick does not explicitly say she disagrees with the ruling in favour of VRR, and no longer believes VRR should have the right to define their own membership and maintain a women-only space, though she does criticize the organization for “excluding trans women.”

In the following letter, Lee Lakeman, a founding member of the Vancouver Rape Relief collective, responds.

~~~

Dear Jude,

Over the last couple of days, three friends have sent me your statement published at Rabble. Like many, I have not read Rabble in years. The suppression there of any debate about ideas not supported by the party put me off. As it happens, I was reading the work of a young feminist in New Zealand writing about the barriers and difficulties of responding with integrity to the events in our lives. So, with her example, I think it best that I try.

You published your piece, “My Feminist is Trans Inclusive,” at Rabble, so I am submitting to Feminista, Feminist Current, Vancouver Women’s Space and Fairer Disputations, which may not be perfect media, but that’s what I have, just as you have Rabble. Perhaps a friend will forward it to you. If not, then maybe we have no remaining connections. I haven’t yet responded to my other friends who contacted me about your statement, but as you and I have been friends and comrades, my first response is to you:

I’m sorry that you have been pressured to apologize for doing what you thought was your ethical obligation when you provided testimony in the BC Human Rights Court to protect the legislated rights of Vancouver Rape Relief and Women’s Shelter from a wrongful accusation. I was grateful at the time and I remain grateful that you gave of your commitment to women’s liberation. If it is of any consolation to you or if it can satisfy those pressuring you, I don’t think it was your testimony, but rather the BC NDP government’s provision in Human Rights Law, ensuring equality-seeking groups have the right to define their own membership, that convinced the judges. And I’m sure you can argue that you have avoided the many situations since (including those before the various courts now) in which women have asserted this legal right that we confirmed in 2005. I’m sure that this excellent legislation is the real target. They want you to mislead what remains of second wave feminist support for the NDP.

Your explanation that you were ignorant at the time and have been educated since (presumably about whether women get to organize on our own terms) seems unlikely to satisfy those who press you for apology and contrition. It’s obvious that some want to display your contrition, to expose an image of you bowing down in contrite humiliation (perhaps as a cautionary tale before those in debate or confusion) while you still have a Canadian level of fame and importance as the legacy media’s chosen face of second wave feminism.

I must say that such a change of mind and your right to express it is completely understandable given the current state of things and your choice to express a change of mind is something I defend even as I find this change wrongheaded. I hope they are satisfied with this halfway measure and you won’t need further defending.

Those of us who believe the evidence of bodies — especially of our eyes and ears — that sex differences are real and matter, who think and recognize important patterns of oppression based in part on those differences, who still struggle for women’s equality and liberty (and particularly among those of us who struggle against rape, some of whom have chosen to support women’s rights by organizing separately), beg to differ.

Who knows how all this division and disagreement will end, but forcing women or any people to say what they do not perceive, believe, or think; disallowing groups of like-minded women to organize against sexist violence and in our own egalitarian and humanist interests; forcing individuals or groups of the oppressed to stand silent while witnessing the oppression of others; and forcing pathetic examples of insincere contrition or renunciation of women’s genuine efforts does not bode well.

Lee Lakeman

The post A letter to Judy Rebick, from Lee Lakeman, on changing one’s mind appeared first on Feminist Current.

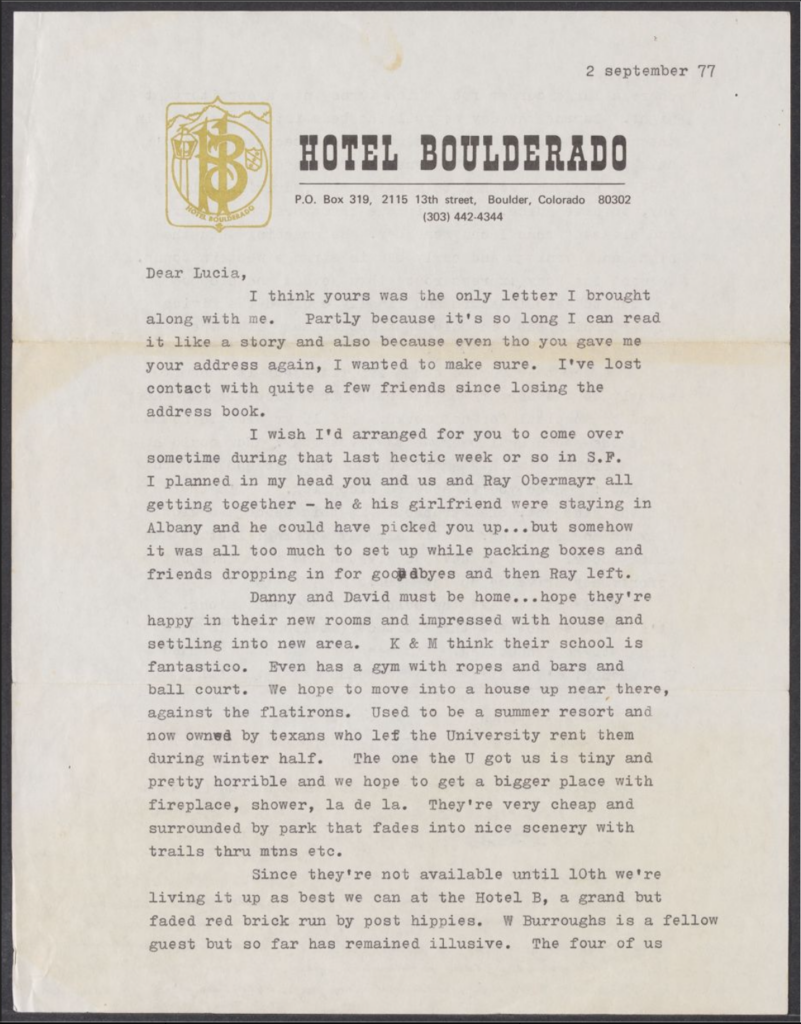

Jennifer Dunbar Dorn’s letter to Lucia Berlin from the Hotel Boulderado, September 2, 1977. Courtesy of Jennifer Dunbar Dorn and the Lucia Berlin Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In 1977, Jennifer Dunbar Dorn wrote to her best friend, Lucia Berlin, from the Hotel Boulderado, where she was staying while she looked for a house in Boulder, Colorado. Her “large corner room” became “a dormitory at night,” while “during the day we roll the beds into a cupboard in the hall.” She described the hotel as a “faded red brick run by post hippies,” a place for people on the make and on the move. This might not seem like a hotel that would have had its own stationery, but it did. The paper’s crest features a lantern and mountains, and the header reads HOTEL BOULDERADO in French Clarendon font: the typeface of Westerns and outlaws, of greed, gambling, and adventure. The hotel’s name, Dunbar Dorn recently pointed out to me, “is a combination of Boulder and Colorado, obviously, but the mythic El Dorado is ingrained everywhere in the West”—its lost city of gold.

I stumbled on this letter at Harvard’s Houghton Library, where a collection of Berlin’s papers are stored in a single cardboard box. Almost everything she saved over the course of her peripatetic life is compressed into this tiny space: correspondence, notebooks, reviews, manuscripts, applications for tenure. I am Berlin’s first biographer, and I often felt deeply moved as I worked through the box last summer. Berlin is my El Dorado, and I had been looking for her for so long … Though the archivists at the library had sent me scans of some of these documents during the pandemic, it wasn’t the same as touching pages she had once touched.

As I examined the yellowed paper, placing my own thumb over the smudged thumbprint at the top, I imagined Berlin reading Dunbar Dorn’s letter at her kitchen table in Oakland after a shift on the Merritt Hospital switchboard. Mostly, it’s about Dunbar Dorn’s journey from California to Colorado with her husband, Ed Dorn, and their children. Her emphasis is on their time on the road, not on their arrival—on transience over stasis and on quest over complacency, core values of the counterculture to which she, Dorn, Berlin, and their dispersed community of writers and artists loosely belonged.

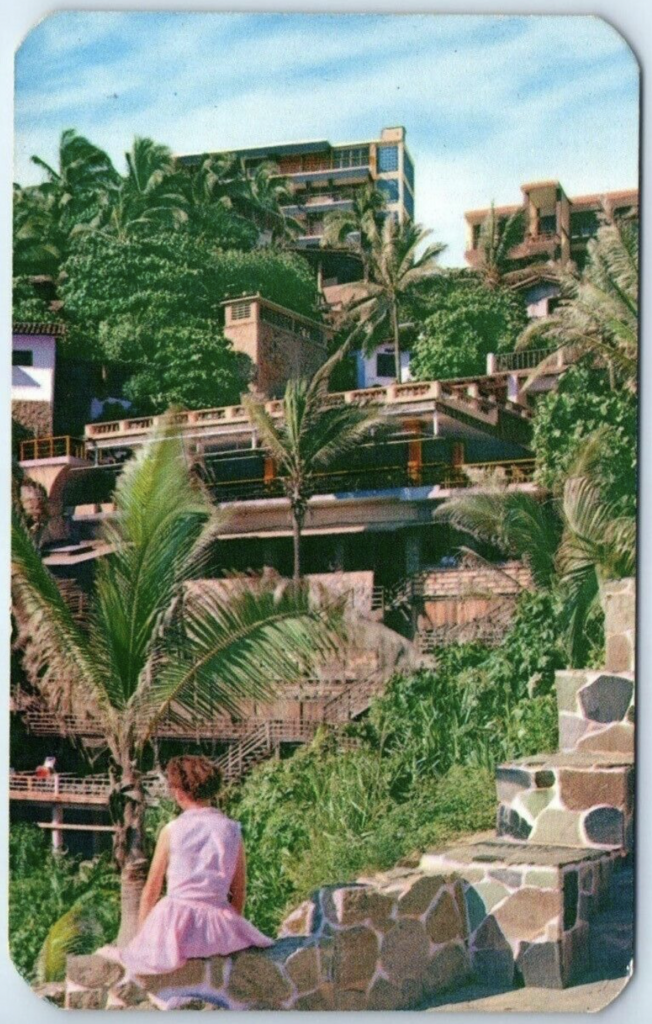

A postcard from the Hotel Acapulco, from the fifties.

The Boulderado letter stood out to me because of the paper on which it was written. I got to Harvard in the third week of a research trip in pursuit of Berlin’s scattered correspondence, and along the way I’d become obsessed with hotel stationery. The appeal, at first, was aesthetic: hotel paper is pretty, and from the forties to the seventies, it was ubiquitous across the States and Europe. A few days earlier, while wading through the papers of Berlin’s literary agent, Henry Volkening, at the New York Public Library, I’d noticed that many of his clients wrote to him from hotels. Berlin herself first used her author name on a hotel postcard to Volkening in 1961. She had just eloped to Acapulco with her third husband, Buddy Berlin, and she described her newfound happiness, signing off: “Lucia Berlin.”

But many of the hotel letters I sought out had nothing to do with Berlin’s work. By my third or fourth archive—in my third or fourth American city—I was skipping lunch breaks to call up boxes belonging to writers who I knew traveled frequently: James Baldwin, Anaïs Nin, Raymond Chandler. Here is some of what I found.

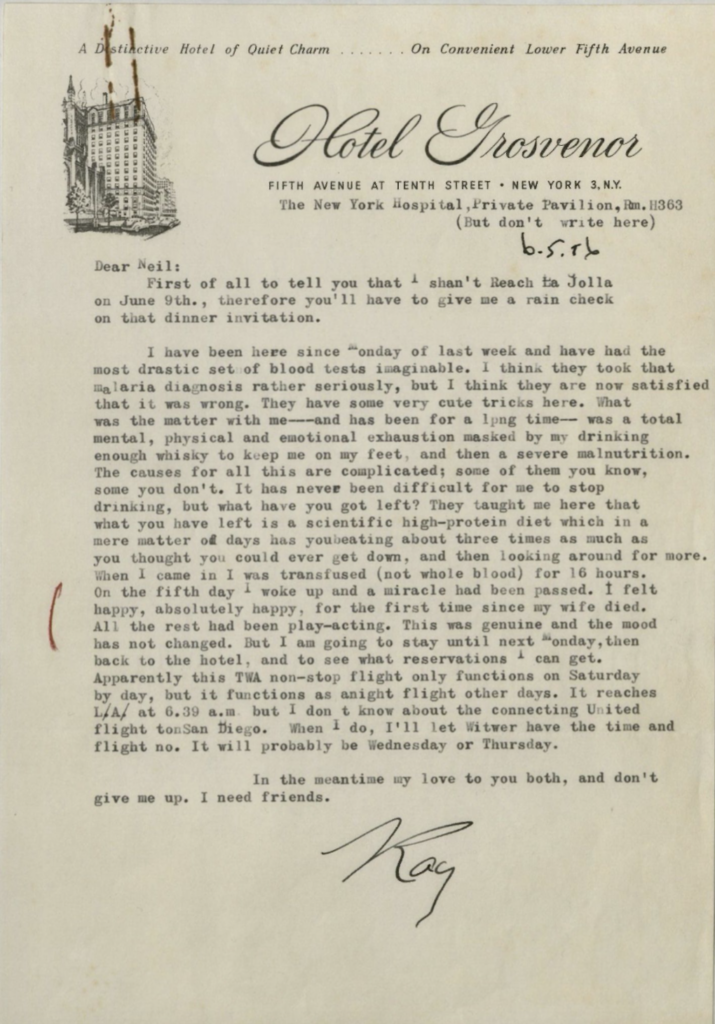

Raymond Chandler’s letter to Neil Morgan from the Hotel Grosvenor, June 5, 1956. © The Estate of Raymond Chandler. Courtesy of the Estate, c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.

The Hotel Grosvenor

Raymond Chandler wrote to his friend Neil Morgan on Hotel Grosvenor paper in 1956, describing a recent bout of “mental, physical and emotional exhaustion” that he dealt with by “drinking enough whiskey to keep me on my feet.” At a second glance, the address on Fifth Avenue is underlined by a second one, of Room H363 at the private pavilion of New York Hospital (“But don’t write here”). Chandler wasn’t at the Grosvenor anymore; he was at the hospital, recovering from a breakdown. The hotel stationery was a respectable front for a man who had been institutionalized but who still wanted the people who loved him to know where he was. “Don’t give me up,” he ends the letter to Morgan. “I need friends.”

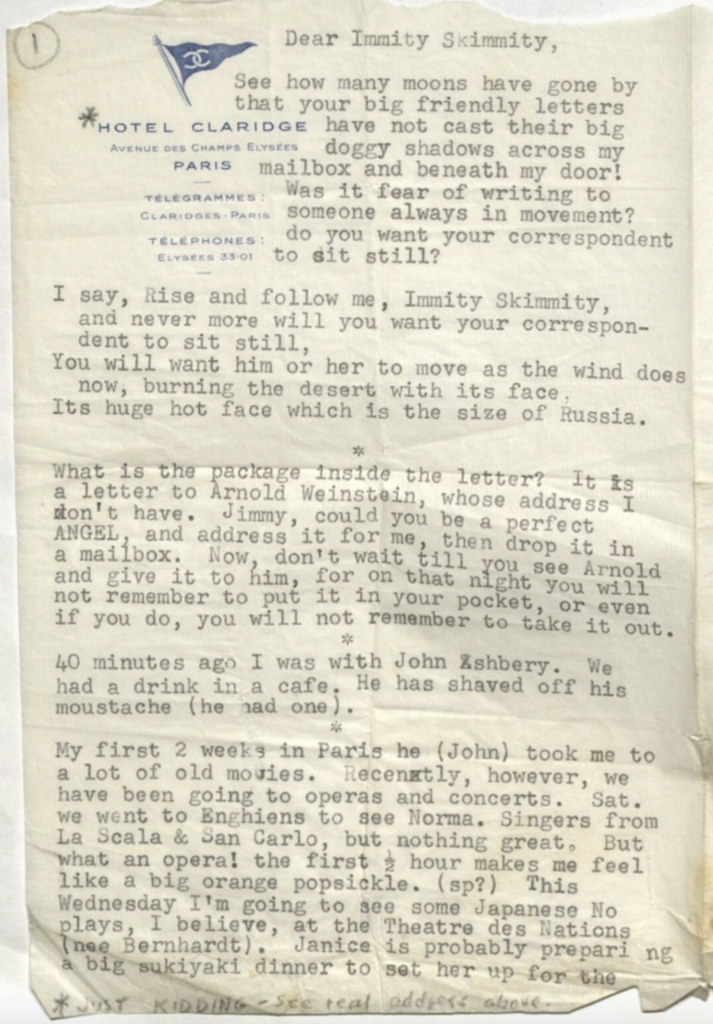

Kenneth Koch’s letter to James Schuyler from the Hotel Claridge, from the late fifties. Courtesy of the Kenneth Koch Estate and the James Schuyler Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of California, San Diego.

The Hotel Claridge

In the late fifties, Kenneth Koch sent James Schuyler a letter on paper from the Hotel Claridge in Paris, a Champs-Élysées institution and a rendezvous for “touristes fortunés,” Koch wonders whether “fear of writing to someone always in movement” is what has kept Schuyler from keeping in touch. He continues with a riff on the New Testament: “Rise and follow me, Immity Skimmity, and never more will you want your correspondent to sit still.” As it was for Berlin and the Dorns, a particular type of transience was, for Koch, a virtue. He traveled to escape the system, not to be coddled in upholstered rooms like the luxury suites at the Claridge. There is an asterisk next to the hotel crest: “Just kidding,” he adds, “see real address above.” This, it turns out, is 41, rue du Cherche-Midi, in the then hip and nonconformist sixth arrondissement, which, since the war, had become the headquarters of existentialism and bebop jazz. He must have swiped the Hotel Claridge stationery; his correspondence wears it as a costume to play a visual trick on Schuyler—to “kid.”

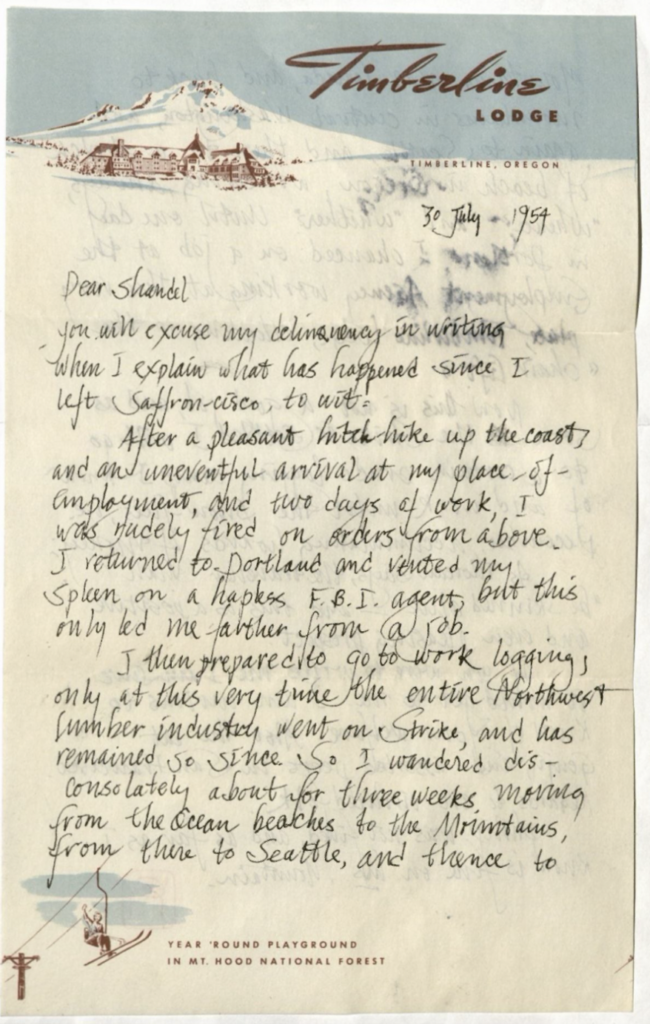

Gary Snyder’s letter to Shandel Parks from Timberline Lodge, July 30, 1954. Courtesy of Gary Snyder and the Gary Snyder Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego.

Timberline Lodge

Hotel stationery leaves plenty of space for editorializing. Gary Snyder wrote to Shandel Parks in 1954 from Timberline Lodge in the Oregon mountains. The hotel’s name and outline appear on the header, and at the bottom of the page there is an illustration of a ski lift, with tiny letters reading YEAR ’ROUND PLAYGROUND IN MT. HOOD NATIONAL FOREST.

Snyder explains to Parks that he has been wandering “disconsolately about,” from “the ocean beaches to the Mountains, from there to Seattle, and thence to Mountains near Canada, and back to Mountains in central Washington, and again to Seattle, and then to a stretch of beach in central Washington, wondering, always, ‘Whence?’ and ‘Whither?’” Finally, he “chanced on a job” at Timberline Lodge, “attending to the «chair lift».” He did not plan to stay long. The double chevrons around “chair lift” are a different shape from the other quotation marks in his text, as though the language of chairlifts is not his own. At Timberline Lodge, Snyder was immersed in an unfamiliar, all-American world of commercialized leisure, one he mocks with his infantilizing caption. He kept its chairlifts running, while maintaining the detachment that pervades his letter to Parks. He makes clear that as soon as the lumber strike in the Pacific Northwest is settled, he “will go to a certain crude logging camp” and “work until the snow flies. i.e. December, accumulating hoards of money.”

Back to the Boulderado

By the time Dunbar Dorn wrote to Berlin in the late seventies, the Hotel Boulderado’s stationery was informed by a countercultural aesthetic that was beginning to enter the mainstream. The whimsical logo and typography suggest that the hotel catered to seekers, dissenters, and outlaws—or to people who saw themselves as such. Guests included William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Ishmael Reed, plus a rotating cast of speakers at the University of Colorado and the Naropa Institute. In his 1975 song “Come Back to Us Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard,” John Prine describes a hippie “buying quaaludes on the phone … In the Hotel Boulderado / at the dark end of the hall.”

And yet the hotel remained, fundamentally, a business. In the eighties, after scraping together funds to renovate, it shed its dissident aesthetic and reverted to the plush accessories and prices with which it had opened in 1908. Today, rooms start at two hundred dollars a night, and the “happenings” advertised on the hotel website include a monthly “wine club” starting at forty dollars per person. Burroughs and rollaway beds are a distant memory.

When I called the Boulderado to ask if they still print their own stationery, the front-office manager told me that they did, but that she used it for official correspondence and welcome letters to guests. Branded paper is no longer placed in the rooms. And this brings something home: no matter how closely I follow Berlin, I can never truly enter her world, because it is gone, along with the golden age of hotel stationery. What endures, of course, is Berlin’s work. In her short story “Dr. H. A. Moynihan,” originally published under the title “The Legacy” in 1982, a dentist shows his granddaughter a set of false teeth. “He had changed only one tooth,” Berlin writes, “one in front that he had put a gold cap on. That’s what made it a work of art.” I think, for her, this was a metaphor for the creative process. She does something similar with her fiction, drawing on her experience and transforming it, too, as Lydia Davis has observed. And her interventions, innovations, additions, and omissions catch the light: they’re the treasures, like El Dorado, or the gold cap on a tooth.

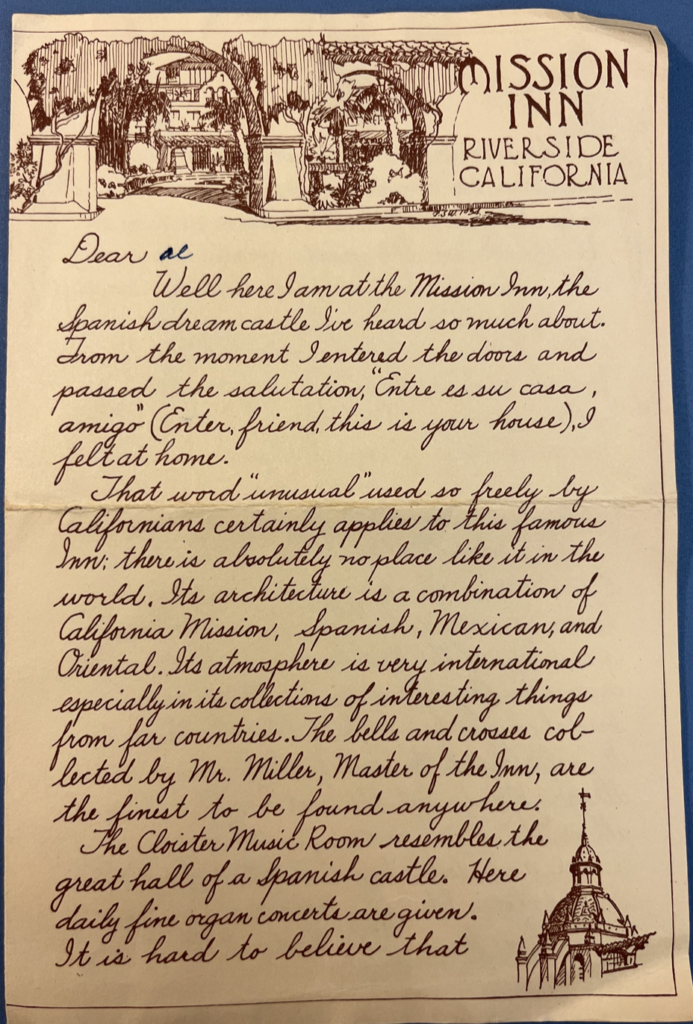

A prewritten hotel letter from the Mission Inn, March 14, 1946.

Nina Ellis is a British American writer and scholar. Her short stories and essays have appeared in Granta, The Idaho Review, The London Magazine, the Oxford Review of Books, and elsewhere. She won an Editors’ Choice Award in the 2021 Raymond Carver Short Story Contest. Looking for Lucia: A Biography will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2025.

English professors shouldn't repeat romanticized myths about the state of their field.

Note 19

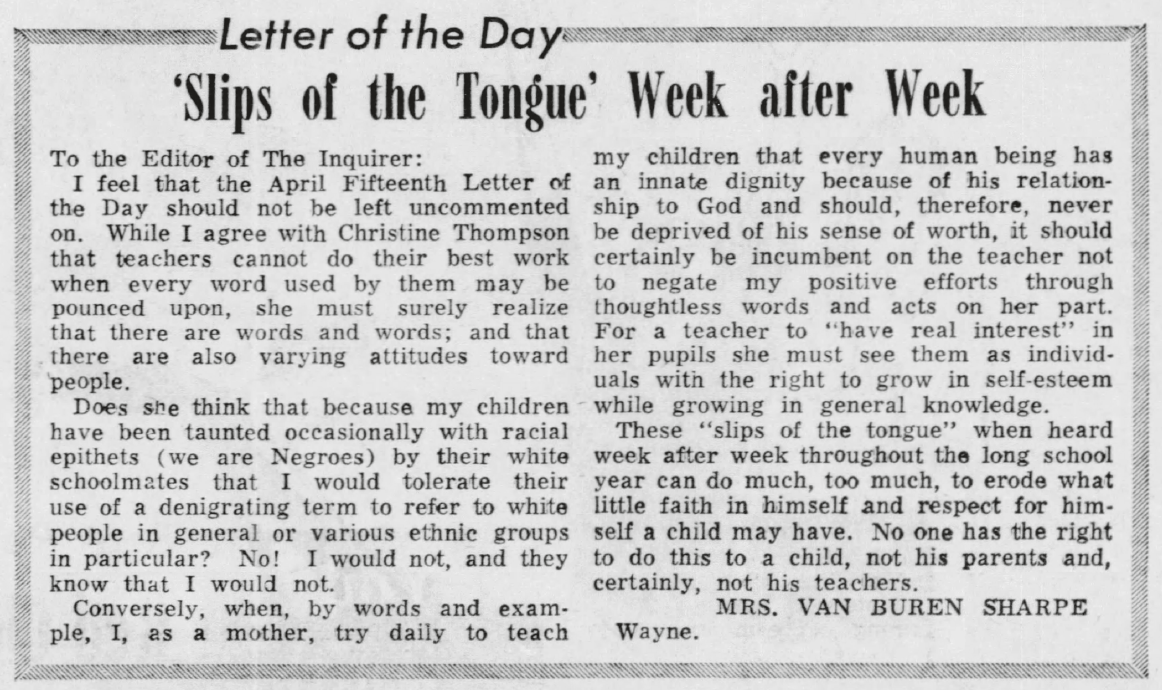

Letters to the Editor: ‘Slips of the Tongue,’ Week after Week

April 19, 1967

Courtesy of Christina Sharpe.

Note 20

Letters to the Editor: Deep-Seated Bias

December 20, 1986

If anyone has seriously been entertaining doubts that deep-seated prejudice is alive and thriving in the United States, he has only to read the December 9 front-page article in the Inquirer concerning the fourteen-year-old girl who was a rape victim to disabuse himself of this naive notion. Here we have a situation cast in the classic mold of the pre–civil rights era. A white female is raped (by a white male whom she knows) but, when describing her assailant, she does not describe a bogus white male but chooses to describe her attacker as a nonexistent black male. How sad that this fourteen-year-old child apparently instinctively chose a member (albeit a fictitious one) of another race to be her victim.

Ida Wright Sharpe

Wayne

Note 21

Letters to the Editor: Racist Asides

March 2, 1992

While I sympathize with Jack Smith’s son who was given a traffic ticket because of the flashing lights on his car (after all, are they any more distracting than the vanity plates that one tries to read in passing?), I am more concerned about the gratuitous comments made by Mr. Smith.

His remark that the car “looked as if it had just rolled out of the barrio” is blatantly racist, as is his question about the lights being “overly … Latino.” Is one to believe, as Jack Smith apparently does, that on the Main Line only Spanish-speaking individuals drive cars that have anything other than the names of universities and yacht clubs embellishing the rear windows?

I don’t know how long Jack Smith has been a resident of Wayne, but I have lived here for over thirty-eight years and can assure him that 90 percent of the individuals whom I have seen over the years getting in and out of highly decorated vehicles have been white males of assorted ages.

In the meantime, he needs to work on his racist assumptions about the other kids on the Main Line; some of them—many of them in fact—are not white and none of them deserves to be pigeonholed and disparaged by people like Jack Smith.

Ida Wright Sharpe

Wayne

Note 22

Dear Dr. Sharpe,

It has been over forty years, and this message is long overdue. My XXXXXX is in a PhD program at XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX and has been reading In the Wake. XXX reached out to me because she thought I would really appreciate and enjoy it, especially because XXX noticed so many connections to schools I attended and worked for over the years. I was so proud to tell XXX we were once classmates. As you probably know, my years in grade school were incredibly unhappy, and I just wanted to let you know that you and XIXX were the only two in the class who made it bearable for me. I observed so many similar problems when I was XXXXXXX at XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX, and that is why I made the decision to leave this year. I felt like I was giving up on the school and so many students, but there are so many pervasive issues in that community, and I was sorry to see there was no appetite to make any changes.

I know we had our own adolescent issues many years ago, but I wanted to thank you for your friendship during a very lonely time in my life, and for the impact you have had on my XXXXXX.

Warm and best regards,

XXXXXXXXXXXXX

NOTE 23

And three days later, another note arrives.

Dear Christina,

You probably don’t remember me, but you have been on my mind and I finally decided to try to find you. I am XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX and we went to school together. I am back living in XXXXXXX after many years outside of the area and drive by your old house frequently, reminding me of you and your mom. Having seen people from high school that haven’t changed made me wonder about the people I was really interested in, and you are one of them. I see my high school self as such a small part of what I am now, and am glad that I have rich life experiences.

I don’t know if you are ever back in the Philadelphia area, but would be interested to see you again and hear more about your life. Google is a wonderful tool, but only tells part of the story. From reading about your writing and teaching, I think you would be interested in a friend of mine from XXXXXXXXXXXX, XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX and XXX latest book. If you know XXX, even better.

Wishing you a wonderful day, and hope our paths cross in the future.

XXXXXXXXXXXX

Adapted from Ordinary Notes, to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April.

Christina Sharpe is the author of In the Wake: On Blackness and Being and Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects. She is Canada Research Chair in Black Studies in the Humanities at York University.

The documentary filmmaker and sports editor Paul Devlin has won five Emmy awards, but he may well be better known for not getting into Harvard — or rather, for not getting into Harvard, then rejecting Harvard’s rejection. “I noticed that the rejection letter I received from Harvard had a grammatical error,” Devlin writes. “So, I wrote a letter back, rejecting their rejection letter.” His mother then “sent a copy of this letter to the New York Times and it was published in the New Jersey section on May 31, 1981.” In 1996, when the New York Times Magazine published a cover story “about the trauma students were experiencing getting rejected from colleges,” she seized the opportunity to send her son’s rejection-rejection letter to the Paper of Record.

It turned out that Devlin’s letter had already run there, having long since gone the pre-social-media equivalent of viral. “The New York Times accused me of plagiarism. When they discovered that I was the original author and they had unwittingly re-printed themselves, they were none too happy. But my mom insists that it was important to reprint the article because the issue was clearly still relevant.”

Indeed, its afterlife continues even today, as evidenced by the new video from Letters Live at the top of the post. In it actor Himesh Patel, well-known from series like EastEnders, Station Eleven, and Avenue 5, reads aloud Devlin’s letter, which runs as follows:

Having reviewed the many rejection letters I have received in the last few weeks, it is with great regret that I must inform you I am unable to accept your rejection at this time.

This year, after applying to a great many colleges and universities, I received an especially fine crop of rejection letters. Unfortunately, the number of rejections that I can accept is limited.

Each of my rejections was reviewed carefully and on an individual basis. Many factors were taken into account – the size of the institution, student-faculty ratio, location, reputation, costs and social atmosphere.

I am certain that most colleges I applied to are more than qualified to reject me. I am also sure that some mistakes were made in turning away some of these rejections. I can only hope they were few in number.

I am aware of the keen disappointment my decision may bring. Throughout my deliberations, I have kept in mind the time and effort it may have taken for you to reach your decision to reject me.

Keep in mind that at times it was necessary for me to reject even those letters of rejection that would normally have met my traditionally high standards.

I appreciate your having enough interest in me to reject my application. Let me take the opportunity to wish you well in what I am sure will be a successful academic year.

SEE YOU IN THE FALL!

Sincerely,

Paul Devlin

Applicant at Large

However considerable the moxie (to use a wholly American term) shown by the young Devlin in his letter, his reasoning seems not to have swayed Harvard’s admissions department. Whether it would prove any more effective in the twenty-twenties than it did in the nineteen-eighties seems doubtful, but it must remain a satisfying read for high-school students dispirited by the supplicating posture the college-application process all but forces them to take. It surely does them good to remember that they, too, possess the agency to declare acceptance or rejection of that which is presented to them simply as necessity, as obligation, as a given. And for Devlin, at least, there was always the University of Michigan.

Related content:

Read Rejection Letters Sent to Three Famous Artists: Sylvia Plath, Kurt Vonnegut & Andy Warhol

T. S. Eliot, as Faber & Faber Editor, Rejects George Orwell’s “Trotskyite” Novel Animal Farm (1944)

Gertrude Stein Gets a Snarky Rejection Letter from Publisher (1912)

Meet the “Grammar Vigilante,” Hell-Bent on Fixing Grammatical Mistakes on England’s Storefront Signs

Steven Pinker Identifies 10 Breakable Grammatical Rules: “Who” Vs. “Whom,” Dangling Modifiers & More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Twice a month, The Rumpus brings your favorite writers directly to your IRL mailbox via our Letters in the Mail program.

Erica Berry is a writer and teacher based in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. Her nonfiction debut, Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear, was published by Flatiron and Canongate in early 2023. Other essays appear in Outside, The Yale Review, The Guardian, Literary Hub, The New York Times Magazine, Gulf Coast, and Guernica, among others. Winner of the Steinberg Essay Prize, she has received grants and fellowships from the Ucross Foundation, Minnesota State Arts Board, the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, and Tin House.

The Rumpus: What book(s) made you a reader? Do you have any recent favorites you’d like to share?

Erica Berry: I recently read Guadalupe Nettel’s Still Born, which was just longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and which I bought while teaching in the U.K. last summer, in part because I am just always drawn to what is hiding behind the stark white and blue of Fitzcarraldo Editions covers. I found it a totally propulsive novel, lyrically exploring the contradictions and societal pressures of motherhood, womanhood, etc. I was also stunned by The Story of a Brief Marriage, by Anuk Arudpragasam, which unfolds over just a few days in a Sri Lankan refugee camp amidst the civil war, with a granularity that was so gorgeously, delicately rendered in a very short book, while also raising larger questions of how we love amidst crisis. What does it mean, really, to tie ourselves to another body? I’d also be remiss not to mention a few wonderful nonfiction books: I was awed by the intellectual inquiry in Amia Srinivasan’s The Right to Sex, and am currently loving Doreen Cunningham’s researched memoir Soundings, about whales and migrations and family more broadly.

Rumpus: How did you know you wanted to be a writer?

Berry: I think of one day in middle school, when I was dreading a camping trip required for my whole class from school, and my father—he was in the driver’s seat—told me that it would be okay if it wasn’t all fun. In those moments, he said, I could think of myself like an anthropologist or a journalist, and thereby create a little distance from living the drama, I could be observing it instead. He told me he was looking forward for me coming back to tell him the stories I had learned. I already knew writing as a form of self-expression, but until then I had not understood that storytelling was also a way of making the world more bearable. Even things that were challenging to bear IRL could be made palatable—or at least a bit more legible—by wrestling them into story. I suppose I grew up feeling like I was always a bit too curious and too sensitive, and writing let me see both those things as assets. I was hooked.

Rumpus: What’s a piece of good advice or insight you received in a letter or note?

Berry: My best friend from college and I have a very close, joke-y relationship, but our senior year, she slipped a note under my door explaining that the way I’d told a story about her at dinner had rubbed the wrong way, and she felt a bit hurt. I felt horrible, truly like the worst person, but, at the same time, overcome with gratitude—she knew our relationship could bear the honesty. I struggle with confrontation, and I was awestruck by how gracefully she’d pulled it off. For years I saved her note. It was a reminder of who I wanted to be as a friend—the sort of person who expected more from the people around me, and was always working to strengthen those ties.

Rumpus: Tell us about your most recent book? How do you hope it resonates with readers?

Berry: Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear is a weave of memoir, history, science, psychology, folklore and cultural criticism, telling three central stories: my own coming-of-age encounters with fear, the story of real wolves coming back into Oregon, and the legacy of ’symbolic wolves’ across time and space. When I started the book, I didn’t even consider myself an ‘animal person,’ and a part of me wanted to try and write a wolf book that made space for readers who might not think they would have any reason to read one. Whatever a reader’s preexisting relationship with wolves, I hope the larger life questions resonate: How do we evaluate our fears, and at what cost both to ourselves and to the world? How can we best share the world with one another, human and animal?

Henriette Lazaridis’ novel Terra Nova (Pegasus Books, 2022) was called “ingenious” and “provocative” by the New York Times. Her debut novel The Clover House was a Boston Globe bestseller and a Target Emerging Authors pick. Her short work has appeared in publications including Elle, Forge, Narrative Magazine, The New York Times, New England Review, The Millions, and more, and has earned her a Massachusetts Cultural Council Artists Grant. Henriette earned degrees in English literature from Middlebury College, Oxford University, where she was a Rhodes Scholar, and the University of Pennsylvania. Having taught English at Harvard, she now teaches at GrubStreet in Boston and runs the Krouna Writing Workshop in Greece. She writes the Substack newsletter The Entropy Hotel, at henriettelazaridis.substack.

The Rumpus: What book(s) made you a reader? Do you have any recent favorites you’d like to share?

Henriette Lazaridis: I still have my copy of James Ramsay Ullman’s Banner in the Sky, and you can tell from how beat up it is that I read it and over and over. I loved that book. I imagined myself as Rudi, the main character who climbs a mountain that’s a lot like the Matterhorn to succeed on the climb that killed his father. I loved to hike, and this mountain climbing adventure captured my imagination and got me into reading all sorts of other adventure books, like Treasure Island and Kidnapped.

Among the many recent wonderful books I’ve read, I keep going back to Shrines of Gaiety, by Kate Atkinson. It’s not my favorite of hers, but it’s her latest, and it filled my need to be in the presence of her narrator once again–a narrator who does things I don’t think I’ve seen any other narrator quite do. Reading Atkinson is almost painful, she’s so good. It’s like speaking a language you know you can communicate in but whose real meaning keeps eluding you.

Rumpus: How did you know you wanted to be a writer?

Lazaridis: I talked the talk starting in middle school, and wrote for the school magazines and all that. I left my career in academia after fifteen years to return to fiction writing. But I didn’t really understand that that was what I wanted to do until I’d gotten yet one more letter in a stream of rejections and decided to burn all my manuscripts (Really. I looked up the regulations for a bonfire in your backyard and I was good to go.). I got some excellent advice from those who best knew me, and I didn’t light that bonfire. I realized I had to go all in, no hedging bets, no self-sabotage, no easy way out, if I wanted to really call myself a writer.

Rumpus: What’s a piece of good advice or insight you received in a letter or note?

Lazaridis: I can quote it by heart. It was one of the pieces of excellent advice I got, from my then husband, when I was trying to figure out if I should just quit this whole writing thing. “You can’t burn to reach a dream while seeking to protect yourself in case of failure.” Dammit, he was right.

Rumpus: Tell us about your most recent book? How do you hope it resonates with readers?

Lazaridis: Terra Nova is about two Antarctic explorers in 1910 and the woman back in London who loves them both. While the men are racing to be first to the South Pole, Viola aims at new achievements of her own, as a photographer and artist involved in the suffrage movement. The book explores questions of ambition and rivalry and kinds of love. I would hope readers would come away from the novel asking themselves how far would they go to achieve their own ambitions? How much would they be willing to sacrifice–and to ask others to sacrifice–in order to reach their goals?

Rumpus: What is your best/worst/most interesting story that involves the mail/post office/mailbox?

Lazaridis: During my childhood summers visiting my family in Greece, I’d go to the local kiosk and buy that week’s edition of the Mickey Mouse comic, in Greek. My grandmother and I would read it together, with the images helping me figure out the words. When I went back to the States for the school year, my grandmother would send me those comics from Athens every week, to help me keep up with my reading. (Greek was my first spoken language but the second one I learned to read.) Those comics came like clockwork, delivered in brown wrapping paper to my mailbox in New England, decorated with an array of Greek stamps, week after week. I loved the stamps, I loved the comics, but most of all, I loved having mail addressed to me–just me–every single week.

***

The university system's new policy banning fully online degrees ignores the needs of today's students and leans on outdated information.

There is cosmic consolation in knowing what actually happens when we die — that supreme affirmation of having lived at all. And yet, however much we might understand that every single person is a transient chance-constellation of atoms, to lose a beloved constellation is the most devastating experience in life. It feels incomprehensible, cosmically unjust. It feels unsurvivable.

In the final years of his short and loss-riddled life, Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817–May 6, 1862) wrote in his diary:

I perceive that we partially die ourselves through sympathy at the death of each of our friends or near relatives. Each such experience is an assault on our vital force. It becomes a source of wonder that they who have lost many friends still live. After long watching around the sickbed of a friend, we, too, partially give up the ghost with him, and are the less to be identified with this state of things.

Thoreau’s life of losses had begun seventeen years earlier. He was twenty-five when his beloved older brother died of tetanus after cutting himself shaving — a gruesome death, savaging the nervous system and contorting the body with agony. Thoreau grieved deeply. A lifelong diarist, he slipped into a five-week coma of the pen. He tried to listen to the music-box, which had always flooded him with delight, but the sounds came pouring out strange and hollow.

Eventually, the fever dream of grief broke into a new orientation to death. Two months into his bereavement, as the harsh New England winter was cusping into spring, Thoreau wrote to a friend — a letter quoted in the altogether wonderful book Three Roads Back: How Emerson, Thoreau, and William James Responded to the Greatest Losses of Their Lives (public library):

What right have I to grieve, who have not ceased to wonder? We feel at first as if some opportunities of kindness and sympathy were lost, but learn afterward that any pure grief is ample recompense for all. That is, if we are faithful; for a great grief is but sympathy with the soul that disposes events, and is as natural as the resin on Arabian trees. Only Nature has a right to grieve perpetually, for she only is innocent.

Having resumed his journal, he took up the subject in the privacy of its pages:

I live in the perpetual verdure of the globe. I die in the annual decay of nature. We can understand the phenomenon of death in the animal better if we first consider it in the order next below us the vegetable. The death of the flea and the Elephant are but phenomena of the life of nature.

This was a season of losses in Thoreau’s universe. His friend and mentor Emerson, who had hastened to stay with him and nurse him in the wake of his brother’s death, lost his beloved five-year-old son to scarlet fever, as incurable as tetanus in their era. Now it was Thoreau’s turn to comfort his friend. Leaning on his new acceptance of the naturalness of death as an antidote to grief, he wrote to Emerson:

Nature is not ruffled by the rudest blast. The hurricane only snaps a few twigs in some nook of the forest. The snow attains its average depth each winter, and the chic-a-dee lisps the same notes. The old laws prevail in spite of pestilence and famine. No genius or virtue so rare and revolutionary appears in town or village, that the pine ceases to exude resin in the wood, or beast or bird lays aside its habits.

An epoch before Rilke insisted that “death is our friend precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love,” and a century and a half before Richard Dawkins considered the luckiness of death, Thoreau adds:

Death is beautiful when seen to be a law, and not an accident — It is as common as life… Every blade in the field — every leaf in the forest — lays down its life in its season as beautifully as it was taken up. When we look over the fields we are not saddened because these particular flowers or grasses will wither — for their death is the law of new life.

Couple these fragments from Three Roads Back with Thoreau on nature as prayer, then revisit the neuroscience of grief and healing, Emily Dickinson on love and loss, Seneca on the key to resilience in the face of loss, and Nick Cave on grief as a portal to aliveness.

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

An article about the university's expansion of virtual education asked the wrong questions about the quality of the courses.

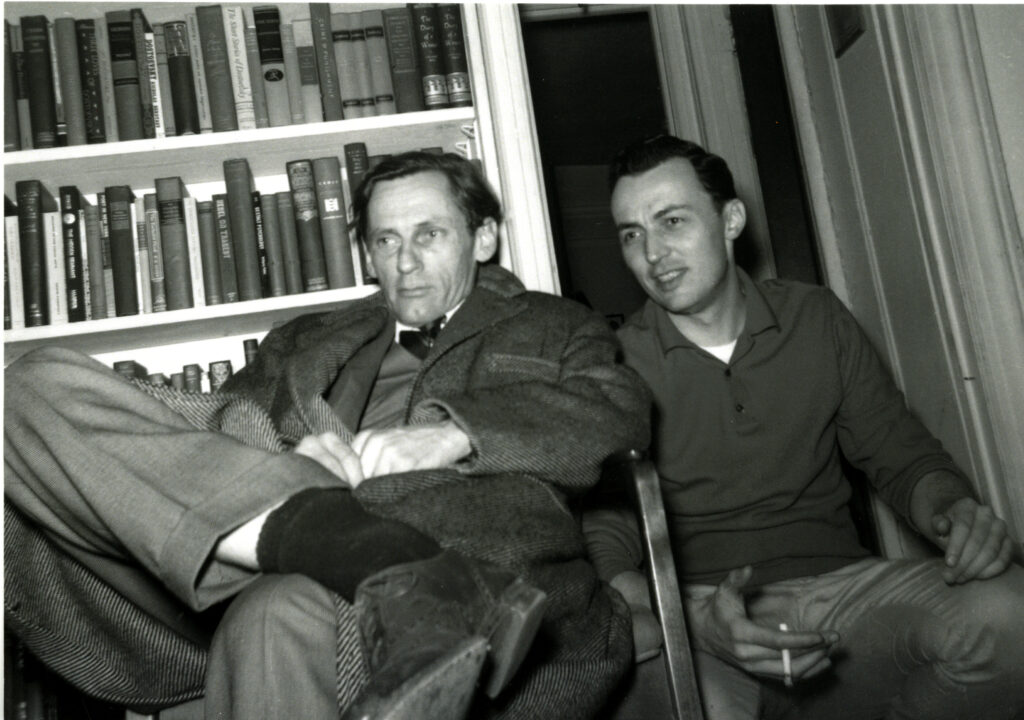

William Gaddis and David Markson. Courtesy of the estate of William Gaddis.

Although William Gaddis’s first novel, The Recognitions, is now regarded as one of the great American novels of the second half of the twentieth century, it was panned upon its publication in March 1955. Among the early few who recognized its greatness was the future novelist David Markson, who read it shortly after it came out, was so impressed that he reread it a month or two later, and then decided to write Gaddis a fan letter. Too depressed by the book’s reviews, Gaddis filed away the letter unanswered. Markson proselytized vigorously on the novel’s behalf over the next six years: he talked the publisher Aaron Asher into reissuing the remaindered novel in paperback, and in his own first novel, Epitaph for a Tramp, Markson included a scene in which the detective protagonist is poking around a literature student’s apartment and finds in the typewriter the conclusion to an essay: “And thus it is my conclusion that The Recognitions by William Gaddis is not merely the best American first novel of our time, but perhaps the most significant single volume in all American fiction since Moby-Dick, a book so broad in scope, so rich in comedy and so profound in symbolic inference that—” Learning of Markson’s efforts from another fan named Tom Jenkins, Gaddis finally answered Markson’s 1955 letter: “After lo these many (six) years.” They would continue to correspond and saw each other occasionally until Gaddis’s death in 1998.

Markson opens the exchange with a canceled salutation to a minor character in The Recognitions who receives a long, rambling letter, and he continues with allusions to other characters, books, and topics in the novel, rendered in Gaddis’s style.

—Steven Moore

717 Greenwich Street

New York City

11 June 55

Dear Dr. Weisgall William Gaddis:

Christ. Christ, Christ, Christ, Christ, Christ. What I want to know is, outside of perhaps The Destruction of the Destruction of the Destruction, what the hell is left to write? Or read, I mean Chrahst! This drunk staggers up to a sandwich man in Times Square, seeing: Filth in our food, spit in Pepsi Cola, free circular … and lurches off screaming: “Jesus, now there’s nothin left to eat even!” Which is how you make me feel. Of course there’s always the chance of Otto’s Return (to Sorrento?) or, say, They Survived: The Saga of Mr. Inononu and Mr. Schmuck, or even Daddy Was a Monk, by the Bildow baby’s baby (as told to of course Max), but why bother? I mean, Chrahst!

But thanks anyhow.

I get it: the method and the matter, although sometimes less of the matter than I might, lacking certain knowledges; but when where the matter is, as it were, foreign, the patterns are there, and more’s the pity if all the expansion can’t be followed. But then hell, you do explain everything, one time or another, in literal terms: I mean Valentine does actually tell him [Wyatt] he’ll eat his father, and his father does actually tell him that when a king is eaten there’s sacrament, and he does actually say his father was a king; or if you miss the poodle running in circles, can you also miss the uneven teeth and the shape of the ears, or lavender used as a “medium”? (Forgive this: I’m merely trying to indicate awareness of more than the literal.) It’s a remarkably great book, and if there have been two (which I know of) which came before it, the step you’ve taken beyond them is this: that you not only relate present to past (act to myth, I mean Chrahst) but also present to present, reducing things so delightfully to absurdities, yet destroying them not. (I might say “a little always sticks,” or would that be pressing it?) And what in hell am I doing telling you what you’ve done, when all I want to say is … (My, your friend is writing for a rather small audience, isn’t he?) … all I want to say is that if I didn’t write the book myself in another life then you wrote it for … (O Doctor, how the meek presume) … for me. And so thanks.

Listen: what I mean is, there are “moments of exaltation” in discovery, also. And obviously I don’t merely mean that I “get it.” There are things like, say, Anselm, after raving, suddenly: “A duet … sung by women, women’s voices,” or … say, Esme, alone … or for Christ sake even poor old Mr. Feddle and that faked dust jacket. And God God the laughter, and where were you when the … Oh the hell, I just thought you would be pleased to know that someone knows what Gaddis hath wrought.

Thanks.

Does this make any sense? I don’t write to “authors” (although I must admit I’ve been known to scribble authors’ inscriptions in friends’ books—bibles only—and damn it no matter how far beyond it all a guy thinks he is, you do manage to have him squirming at times). Anyhow, nothing is intended here. Probably there is a customary way: Dear Mr. Gaddis, I just loved your gorgeous book and I think Mithra is so charming and … I ask you, if Rose was mad, is rose madder?

Do you know Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano? It is the only other thing I know outside of Joyce with so much “amplifying experience” tied together so well. (The terms are difficult to avoid; I mean much more than that.) Anyhow I don’t know many better compliments than the comparison. Or do I sound like the reviews: this book must be compared to Ulysses BUT. God, how they are unaware of the self-devastation of their own ironies, or for that matter of their ironies themselves. Must be compared but: and oh, the militant stupidity of that piece by Granville Hicks [in the New York Times Book Review]. What a charming bloody situation it is when you have to accustom yourself to the profound subtleties of their unawareness in order to know which books are probably worth reading. But what the hell, a work of art is more than a think of “perfect necessity”; it is also an undeniable fact. It exists. Est ergo est. And damned few other brands can make that statement.

In the Viareggio [a bar in the novel]:

—Willie Gaddis? Who doesn’t know him?

—If you can call my mother Jocasta, and me narcissistic …

—That book. He used to run into Harcourt Brace twice a week screaming about this great conversation he heard last night, he had to get it in.

—Listen, your mother still slips a toothbrush into her purse before she goes out to the bar.

—Well, a couple hundred pages, but I mean Chrahst, so the guy’s read everything, I mean why bother …

—My mother …

—I know this guy, says it’s the best book in years. Symbolic for Christ sake. I mean anything that’s a little obscure …

Listen, listen, listen: this could go on forever. You done good, which is all there is to say. If you are ever around I would very much like to catch you for a drink or two (above Fourteenth Street) but that is neither here nor there. But you’ve heard the bells, ringing you on, and what else matters?

With much admiration,

David Markson

New York City 3, New York

28 February 1961

Dear David Markson.

After lo these many (six) years—or these many low (sick) years—if I can presume to answer yours dated 11 June ’55: I could evade embarrassment by saying that it had indeed been misdirected to Dr. Weisgall and reached me only now, but I’m afraid you know us both too well. In fact I was in low enough state for a good while after the book came out that I could not find it in me to answer letters that said anything, only those (to quote yours again) that offered “I just loved your gorgeous book and I think Mithra is so charming …” Partly appalled at what I counted then the book’s apparent failure, partly wearied at the prospect of contention, advice and criticism, and partly just drained of any more supporting arguments, as honestly embarrassed at high praise as resentful of patronizing censure. And I must say, things (people) don’t change, just get more so; and I think there is still the mixture, waiting to greet such continuing interest as yours, of vain gratification and fear of being found out, still ridden with the notion of the people as a fatuous jury (counting reviewers as people), publishers the police station house (where if as I trust you must have some experience of being brought in, you know what I mean by their dulled but flattering indifference to your precious crime: they see them every day), and finally the perfect book as, inevitably, the perfect crime (the point of this last phrase being, for some reason which insists further development of this rambling metaphor, that the criminal is never caught). So, as you may see by the letterhead on the backside here, I am hung up with an operation of international piracy that deals in drugs, writing speeches on the balance of payments deficit but mostly staring out the window, serving the goal that Basil Valentine damned in “the people, whose idea of necessity is paying the gas bill” … (a little frightening how easily it all comes back). But sustained by the secret awareness that the secret police, Jack Green and yourself and some others, may expose it all yet.

This intervention by Tom Jenkins was indeed a happy accident (though, to exhaust the above, there are no accidents in Interpol), and I was highly entertained by the page-in-the-typewriter in your Epitaph for a Tramp. I of course had to go back and find the context (properly left-handed), then back to the beginning to find the context of the context, and finally through to the end and your fine cool dialogue (monologue) which I envied and realized how far all that had come since ’51 and 2, how refined from such crudities as “Daddy-o, up in thy way-out pad …” And it being the only “cop story” (phrase via Tom Jenkins) or maybe second or third that I’ve read, had a fine time with it. (And not that you’d entered it as a Great Book; but great God! have you seen the writing in such things as Exodus and Anatomy of a Murder? Can one ever cease to be appalled at how little is asked?)

I should add I am somewhat stirred at the moment regarding the possibility of being exhumed in paperback, one of the “better” houses (Meridian) has apparently made an offer to Harcourt Brace, who since they brought it out surreptitiously in ’55 have seemed quite content to leave it lay where Jesus flung it, but now I gather begin to suspect that they have something of value and are going to be quite as brave as the dog in the manger about protecting it. Though they may surprise me by doing the decent and I should not anticipate their depravity so high-handedly I suppose. Very little money involved but publication (in the real sense of the word) which might be welcome novelty.

And to really wring the throat of absurdity—having found publishers a razor’s edge tribe between phoniness and dishonesty—I have been working on a play, a presently overlong and overcomplicated and really quite straight figment of the Civil War: publishers almost shine in comparison to the show-business staples, as “I never read anything over a hundred pages“ or, hefting the script, (without opening it), “Too long.” The consummate annoyance though being that gap between reading the press (publicity) interview-profile of a currently successful Broadway director whose lament over the difficulty of getting hold of “plays of ideas” simply rings in one’s head as one’s agent, having struggled through it, shakes his head in baleful awe and delivers the hopeless compliment, “… but it’s a play of ideas”—a real escape hatch for everybody in the “game” (a felicitous word) whose one idea coming and going is $. And I’m behaving as though all this is news to me.

Incidentally—or rather not incidentally at all, quite hungrily—Jenkins mentioned from a letter of yours a most provocative phrase from a comment by Malcolm Lowry on The Recognitions which whetted my paranoid appetite, I am most curious to know what he might have said about it (or rather what he did say about it, with any thorns left on). I cannot say I read his book which came out when I was in Mexico, 1947 as I remember, and I started it, found it coming both too close to home and too far from what I thought I was trying to do, and lost or had it lifted from me before I ever resolved things. (Yes, in my case one of the books that the book-club ads blackmail the vacuum with “Have you caught yourself saying Yes, I’ve been meaning to read it …” (they mean Exodus).) But I am picking up a copy for a new look. Good luck on your current obsession.

with best regards,

W. Gaddis

Gaddis’s letter to Markson will be published in The Letters of William Gaddis, to be published by NYRB Classics in November 2023.

William Gaddis (1922–1998) was born in Manhattan and reared on Long Island. The Recognitions was published in 1955 to largely negative reviews, though it found an underground following. J R, his second novel, and A Frolic of His Own, his fourth novel, both won the National Book Award.

David Markson (1927–2010) was born in Albany and lived in New York City until his death. His novels include Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block, Springer’s Progress, and Vanishing Point.

The older you get, the more you realize that facts aren't nearly as fixed as you thought they were. For decades Pluto was a planet. However, if you were part of the generation that ingested that tidbit during grade school and recited it today, everyone would mock your ignorance. — Read the rest

An essay provides outdated advice that could hurt scholars, especially younger ones.

The university's former president disputes an article's "mischaracterization" of his efforts to promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

Twice a month, The Rumpus brings your favorite writers directly to your IRL mailbox via our Letters in the Mail programs. We’ve got one program for adults and another for kids ages 6-12. Next month, subscribers will be receiving letters from Asale Angel-Ajani and Idra Novey, and Elly Swartz and Anya Josephs, respectively.

Asale Angel-Ajani is the author of A Country You Can Leave and Strange Trade: The Story of Two Women Who Risked Everything in The International Drug Trade. She’s held residencies at Djerassi, Millay, Playa, Tin House, and VONA. She is a recipient of grants from the Ford, Mellon, and Rockefeller Foundations. She has a PhD in Anthropology and an MFA in Creative Writing. She lives in New York City.

The Rumpus: What book(s) made you a reader? Do you have any recent favorites you’d like to share?

Asale Angel-Ajani: I lived in the library, basically, so many, many books made me a reader. The first books would have been every Encyclopedia Brown and then, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, followed by Their Eyes are Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston and Mikail Bulgakov’s, The Master and Margarita. Currently, I am loving Sheena Patel’s I’m a Fan. It’s so good. I love books that flips a narrator’s insides and lays them out on the table. I also just started and so far, am enjoying, Tracey Rose Peyton’s Night Wherever We Go. I can’t resist stories that take a new look at historical truths.

Rumpus: How did you know you wanted to be a writer?

Angel-Ajani: There was a brief period in my childhood when I went to church with my grandmother. I was eight and these Sundays belonged to the Holy-Ghost. The church had everything, from speaking in tongues to spontaneous healing. Since my mother was a staunch atheist and I lived in fear of god’s wrath, I wrote an appeal to “him,” asking for my mother to see the error of her ways. The church published my letter in their Mother’s Day newsletter, on the front page, no less. I was so thrilled to see my name in print, followed by words I wrote, that I didn’t shed a tear when my mother beat me for putting her sinner’s business out in the streets. That’s when I learned the power of words and importantly, the power of an editor, because I was a terrible speller back then.

Rumpus: What’s a piece of good advice or insight you received in a letter or a note?

Angel-Ajani: I would say that the best note I received was from my twin sister, after I proudly sent her a stack of unfinished stories. She wrote back saying, “This is a good start. But none of these will be stories unless you finish them.” Sometimes we just need to be confronted with reality.

Rumpus: Tell us about your most recent book? How do you hope it resonates with readers?

Angel-Ajani: My novel, A Country You Can Leave, centers on a mother and daughter, each trying to figure out who they are and how they are supposed to be in America and to each other. The narrator is a Black bi-racial girl and her mother is a dynamic and demanding immigrant from Russia. It’s also a book about books and love and community. My hope is that readers will find a bit of themselves in the book and that the characters or the setting stays with them for a day or two. And I hope readers laugh. Laughter is always good.

Rumpus: What is your best/worst/most interesting story that involves the mail/post office/mailbox?

Angel-Ajani: My worst story was when I was a feral kid (so I think its way past the statute of limitations) running the streets of my crappy neighborhood with all the other feral kids. There was, what seemed to be, an abandoned house and one day we stole the mail and I brought it home, stuffed it in a drawer. Weeks later, my mother found it, waving all of the social security checks in front of our faces, saying we could go to prison because it was a crime to steal someone’s mail. She made all of us back to the house and put the mail back and apologize to the old woman who lived there.

Rumpus: Is there a favorite Rumpus piece you’d like to recommend?

Angel-Ajani: There is an excellent piece by Stefani Cox, “Searching for Sleeper Trains” published November 4, 2021. It’s a clever piece that does the thing I love in essays: takes seemingly disparate concerns, in this case, insomnia, trains, race and mobility, and the creative process and links them all together to explore history and meaning making. Plus, the writing is lovely.

Idra Novey is the author of Those Who Knew, a finalist for the 2019 Clark Fiction Prize, a New York Times Editors’ Choice, and a Best Book of the Year with over a dozen media outlets, including NPR, Esquire, BBC, Kirkus Review, and O Magazine. Her first novel Ways to Disappear received the 2017 Sami Rohr Prize, the 2016 Brooklyn Eagles Prize, and was a finalist for the L.A. Times Book Prize for First Fiction. Her poetry collections include Exit, Civilian, selected for the 2011 National Poetry Series; The Next Country, a finalist for the 2008 Foreword Book of the Year Award; and Clarice: The Visitor, a collaboration with the artist Erica Baum. She was awarded a 2022 Pushcart Prize for her short story, “Glacier.”

The Rumpus: What book(s) made you a reader? Do you have any recent favorites you’d like to share?

Idra Novey: I relished reading the same fairy tales as a child over and over, seeing how my mind would catch on a detail, or creepy allusion, that didn’t strike me when I read the same words before. Rereading fairy tales and experiencing them differently became a marker to myself of unseen ways I was changing that were imperceptible to my parents and siblings. That habit in childhood of rereading, of anticipating the discovery of a deeper meaning that had escaped me a year before, has remained a habit into adulthood. I’m still drawn to fiction with the deceptively spare prose and foreboding tone of fairy tales, to stories that shift from lightness into darkness in slippery, unexpected ways. A recent favorite book with a fairy tale quality that merits rereading is Claire Keegan’s Foster. Also Patricia Engel’s novel Infinite Country.

Rumpus: Is there a favorite Rumpus piece you’d like to recommend?

Idra Novey: Last summer, I came across Christian Detisch’s beautiful piece in The Rumpus addressed to poet Jay Hopler. Instead of a review, Detisch, who has a day job as a hospital chaplain, had the instinct to write an epistolary piece to Hopler directly, who died a month before the publication of his last book. I found it beautiful that the Rumpus staff allowed for that change in format. It’s so rare to see anyone break with the traditional review format and in this case, given that Jay didn’t live to see the publication of his extraordinary last book of poems, the direct address to him felt right, a way to recognize the haunting absence of Hopler himself in the reception of Still Life.

Rumpus: Tell us about your most recent book? How do you hope it resonates with readers?

Idra Novey: Take What You Need is a novel about familial estrangement and what role art can play in revealing the psychic cost of writing off family members and friends for years. It’s taken me ten books of translation, poetry and fiction to figure out how to write with honesty and complexity about the Southern Allegheny Highlands of Appalachia where I grew up. I hope readers will start Take What You Need for one reason and end up appreciating it most for another reason entirely. I tried to write the novel that way, open to the possibility that every character and scene would subvert my intentions and reveal something about art, trust, and libidinal forces that I didn’t anticipate at all.

This is the last month of our beloved Letters for Kids program <3

March 1 LFK Elly Swartz

March 1 LFK Elly SwartzElly Swartz loves writing for kids, visiting schools, Twizzlers, walking her pups, and doing anything with family. She grew up in Yardley, Pennsylvania, studied psychology at Boston University, and received a law degree from Georgetown University Law Center. Elly is the author of 5 contemporary middle grade novels. Finding Perfect, Smart Cookie, Give and Take, Dear Student, and Hidden Truths (coming 2023). All her books touch on issues of mental health. Connect with Elly at ellyswartz.com, on Twitter @ellyswartz or on Instagram @ellyswartzbooks.

Anya Josephs was raised in North Carolina and is now a therapist working in New York City. When not working or writing, Anya can be found seeing a lot of plays, reading doorstopper fantasy novels, or worshipping their cat, Sycorax. Anya’s short fiction can be found in Fantasy Magazine, Andromeda Spaceways Magazine, and Mythaxis, among many others. Their debut novel, Queen of All, is an inclusive adventure fantasy for young adults available now, with the rest of the trilogy coming soon.

The perceived choice demeans the rationality and intellect of devout Muslims and diminishes the university practices needed to accommodate Muslim students with respect.