Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

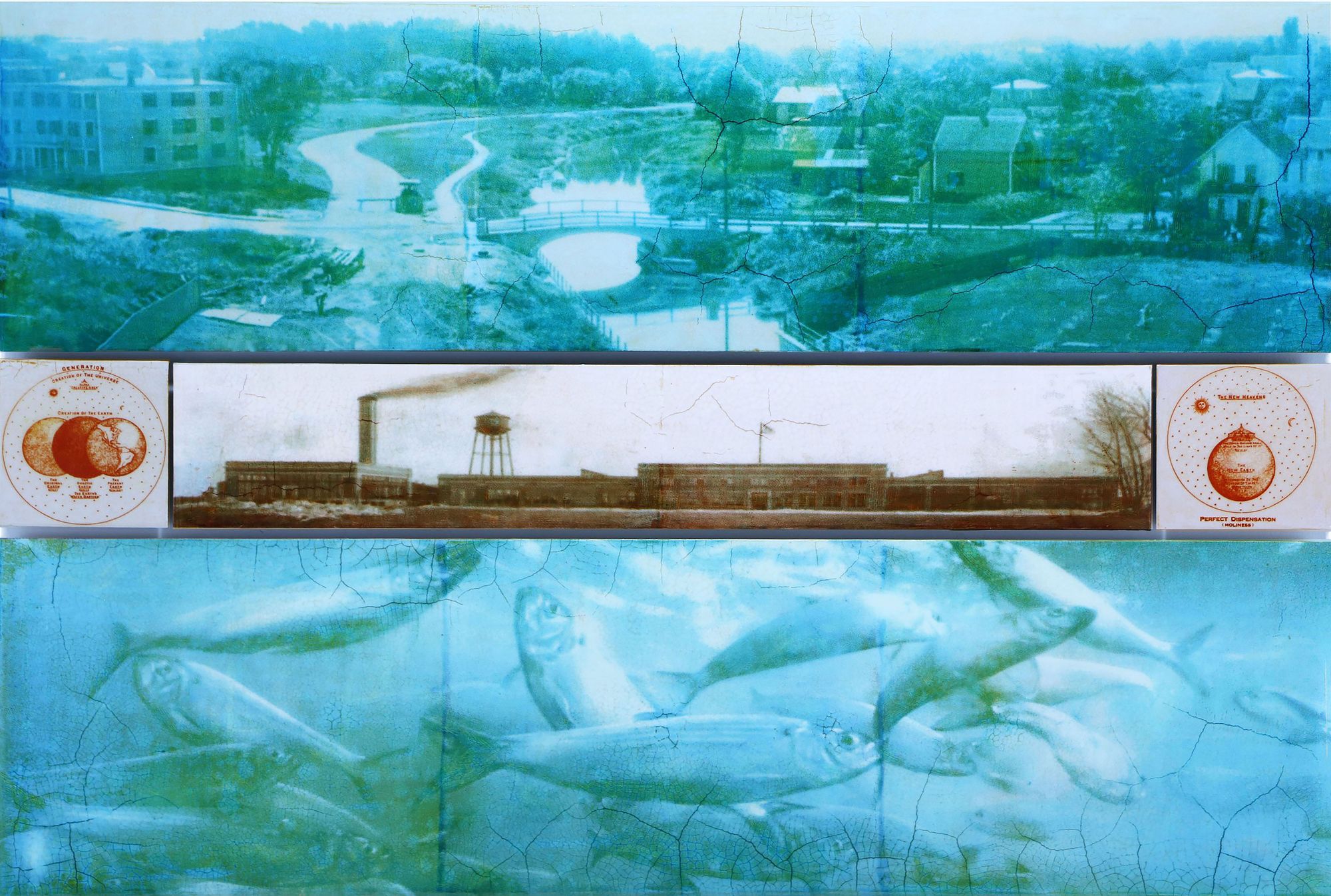

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

After more than 26 years of dedicated service to The Long Now Foundation, Alexander Rose will be stepping down from his role as Executive Director to focus on The Clock of the Long Now, along with his research into the world’s longest-lived organizations. He will continue to serve on the Foundation’s Board of Directors.

For the past quarter century, Alexander Rose – known to his friends and colleagues simply as Zander – has been the engine behind so much of Long Now’s work. Under his leadership, The Long Now Foundation has gone from a fledgling nonprofit to a living, thriving organization, with a vibrant membership program, and twenty years of thought-provoking Talks. He also created The Interval, our combination cocktail bar, cafe, and gathering space in Fort Mason, San Francisco and is an active steward of The Clock of the Long Now.

Zander’s approach to guiding the Foundation has impacted every single one of us at Long Now. In order to properly commemorate his time here, we talked to the people he worked most closely with among Long Now’s staff, Board of Directors, and associates to paint a whole picture of Zander — as Long Now’s leader, but also as a friend and dedicated member of our community.

When The Long Now Foundation was still in a primordial state in the midst of the 01990s, its co-founders Stewart Brand, Danny Hillis, and Brian Eno ran the show. But as the Foundation grew and began to get to work on its core projects, it quickly became clear that Long Now needed a dedicated employee to manage The Clock and The Library. Stewart immediately sought out Zander, who he had known since Zander was just a kid in the junkyards and dockyards of Sausalito, California. Stewart served as “adult supervision” to paintball games and other adventures on the Sausalito waterfront, and to Stewart, Zander’s qualities as a “natural born leader” were clear from a young age. Kevin Kelly, another founding board member and denizen of the Sausalito waterfront, agreed, noting that even at a young age Zander was a tinkerer and skilled paintball tactician, “immediately trying to improve” the crude early paintball equipment and using it to “crush” Kevin, Stewart, and all other challengers.

When Stewart reached out to Zander more than a decade later, Zander, by then a recent graduate of Carnegie Mellon who was looking for work in the field of industrial design, was at first uncertain. As recounted in Whole Earth, John Markoff’s 02022 biography of Stewart Brand, Stewart also helped Zander get job interviews with a number of companies from the contemporary crop of San Francisco Bay Area technology startups. Yet even as he pursued those interviews, Zander couldn’t help but be captivated by the promise Long Now’s Clock and Library projects offered, even in a nascent form.

In the end, his home would be The Long Now Foundation, becoming the organization’s first full time employee and a general project manager, creative leader, and jack-of-all-trades in the Foundation’s early operations. From his first meeting with Zander, Danny Hillis was impressed by his “very practical sense of building things and getting them to work.”

The two would work closely together for years on the preliminary design and prototyping of The Clock of the Long Now. Zander provided a key understanding of, in Danny’s words, the “poetry and the philosophy of the Clock” from the very start. He was able to balance The Clock’s dual nature, holding it as “a machine to be engineered but, on the other hand, a story to be told.”

One early Clock design moment where Zander’s sensibility shone through was in the design of the Clock’s face. In Danny’s recollection, he brought a rough sketch of the astronomical lines he wanted depicted on the Clock’s face to Zander, who proceeded to turn it into the iconic rete design that still serves as part of Long Now’s brand to this day.

For the last few years of the 01990s, Danny, Zander, and a small team of collaborators worked tirelessly to get the prototype ready for their “very hard deadline”: New Years Eve 01999. Without Zander, Danny told us, they wouldn’t have made it:

“I brought my whole family up there and everyone at Long Now was gathered in the Presidio, where we were sharing a space with the Internet Archive. We had finally got all the pieces put together, but when we got them together, we realized that there was a bug in the direction of rotation of one shaft and that it was going to, when it hit the millennium, go from saying, oh, 01999 to 01998 instead of 02000 — the wrong direction.”

“So, there were hours to go before New Year's Day and we had been working on it and I had been traveling and I just said, ‘oh, well this is just kind of hopeless.’ And I actually fell asleep at that point because I was thinking ‘I don't know what's gonna happen, but I am exhausted.’ So I fell asleep. But then Zander figured it out. He realized that we could do it by just remachining one part and so he drove across to Sausalito. And by the time I woke up, Zander had remachined the part. And so when I actually came to midnight it was all put together and sure enough, at midnight it ticked forward and the dial clicked to the year 02000 and the beautiful chime that Zander had chosen, this beautiful Zen bowl chime rang twice. And so the clock chimed in the year 02000 with two bongs in perfect order.”

Zander’s work at Long Now, even in those early days, was not limited to The Clock. The Foundation’s core project has always involved building a cultural institution to deepen our understanding of long-term thinking in parallel to the Clock, and Zander dove into that cause with full commitment.

Along with a dedicated core of early colleagues, Zander helped develop a diverse set of projects that, in their ways, would help foster long-term thinking in the world. These projects included the Rosetta Project, a global collaboration of language specialists and native speakers that aims to preserve the world’s languages using long-term archival devices like microscopically etched disks, and Long Bets, our initiative for long-term predictions and wagers for charity.

Zander didn’t just help get these projects started; he has kept them running for decades as well. Andrew Warner, who has worked as a project manager in Long Now’s programs team for the last decade, says that Zander has “basically done every job at Long Now at some point,” from Clock designer to project manager to maintenance man. Earlier this year, Zander repaired a damaged hot water heater at the Long Now offices the same day he departed on a multi-week research trip on long-lived institutions in India. Throughout all those roles, Zander has maintained his unique sensibility and perspective on leadership. Former Long Now Director of Strategy Nicholas Paul Brysiewicz describes this perspective as a certain “pragmatism” that “does not suffer needless philosophizing.” Long-time Long Now Director of Programs Danielle Engelman cites Zander’s “clear decision-making process after weighing key options & opportunities” as having “kept Long Now's projects and programs moving forward at a pace that belied the small team working on them in the beginning.”

Over the years, Zander has also taken a lead role in one of Long Now's longest-running projects: our speaker series. Since 02020, Zander has acted as the host and co-curator for Long Now's main talk series, bringing together perspectives on long-term thinking from everyone from science fiction authors and artists to scientists, sociologists, and political leaders.

These projects, along with The Clock, helped build a mythos around the Foundation over the years. With this cultivated mythos came interest from the broader culture, with many around the world expressing interest in becoming more involved with Long Now’s work. In response, Zander worked to establish Long Now’s membership program in 02007. According to Danny Hillis, “he really led the idea of the membership program and supported Long Now members. And I think that the original board didn’t really see the potential of that the way that Zander did, but we trusted his intuition on that.”

As Long Now entered its adolescence as an organization, Zander began to research the world’s longest-lasting institutions — groups that had lasted for more than a millennium from businesses to religious orders. This project would later become Long Now's Organizational Continuity Project.

As he studied the records of these organizations, he began to notice a particular, unexpected commonality: across continents and cultural contexts, many of the longest-lived institutions were those that served and produced alcohol, from German breweries to Japanese Sake Houses.

For Zander, the obvious corollary to this finding was to open up a cocktail bar. At first, Long Now’s Board of Directors was skeptical. Running a bar is complicated, and a task far from the core competencies of Long Now at the time. As Andrew Warner put it, “Opening a successful bar is really hard and people didn't really ‘get it’ until it was done.”

But Long Now collectively put their trust in Zander, and he delivered. The Interval, which opened in 02013 after an extensive crowdfunding campaign was “pure Alexander,” per Stewart, with Zander’s fingerprint on everything: its “invention, funding, and peerless delivery.” Danny noted that Zander was especially adept at “getting all the permissions for getting things to happen at Fort Mason,” requiring Zander to use his “political finesse” to navigate the bureaucratic structures of working on federal property.

The Interval, which took the former space of Long Now’s museum and offices and turned it into a world-class cocktail bar, café, and gathering place, was thoroughly shaped by Zander’s influence. As Andrew recounted to us, he even “took the first doorman shift” for the bar’s opening day. Yet perhaps nothing about The Interval’s design speaks to Zander’s unique perspective more than the bar’s Gin Robot. As Nicholas Paul Brysiewicz describes it, “the gin robot at The Interval is the one thing I associate with Zander alone. It’s quintessentially his. It makes billions of gins. It lights up. The lights change color. The only ways it could be more Zandery would involve pyrotechnics.”

Over the past decade, The Interval has become more than just a place to get expertly-crafted cocktails and view the collection of Long Now’s Manual for Civilization. Under Zander’s supervision, the bar has become a place to tell — and to continue — Long Now’s story, a headquarters with a mythos all its own.

Zander’s time at Long Now did not, of course, keep him confined to our offices in Fort Mason in San Francisco. In Long Now’s early days, he traveled extensively with Danny, Stewart, and other board members to explore sites in the American southwest and beyond to find an eventual home for The Clock of The Long Now. As part of that process, Zander became an accomplished rock climber and cave explorer, venturing hundreds of feet into the depths of caves in Texas or mountains in Arizona.

Eventually, Long Now landed on a site at Mount Washington, on the border between Nevada and Utah in the Great Basin, as a likely choice for The Clock. Zander served as a de facto leader for the Long Now team as they explored the many crags and crevices of the mountain. As Danny recounted, “in dangerous situations it's always good to have somebody in charge who's making the decisions and Zander was the one to do that.”

After years of exploration of Mount Washington, Zander and the rest of the team thought they had found nearly all of the useful approaches and pathways within. Yet one particular entrance still eluded them. Inspired by the Siq, a narrow, shaft-like gorge that serves as the grand main entrance to the classical Nabatean city of Petra, Danny and Stewart had imagined a similar pathway as the main approach to The Clock. For years, they searched for it to no avail, until June 21, 02003.

On that day, Zander found a certain opening in what first seemed to Stewart and Danny, his travel companions, to be a “sheer cliff” face on the west side of the mountain. Zander found his way through that passage, a Class 4 crevice, ascending 600 feet alone. “Henceforth,” Stewart told Long Now, “it is known as Zander’s Siq.”

Once the potential sites for The Clock were identified, Zander’s travels did not stop. Instead, he took on a role as a kind of international ambassador for Long Now and for long-term thinking broadly. Those travels have taken him everywhere from the Svalbard seed bank and the far reaches of Siberia to the Hoover Dam, the 1400-year-old Ise Shrine in Japan, and the ancient stepwells of India.

Danny, who accompanied Zander on an early trip to Japan for the rebuilding of the Ise Shrine, which has occurred every 20 years since 00692 CE, recounted that the two of them had been two of the few westerners invited to the rededication ceremony, and the “amazingly moving” feeling of being there with Zander. Afterwards, the Long Now traveling party went to one of the area’s “bottle keep” bars, where patrons can leave part of a liquor bottle reserved for future use for an indefinite period of time. Zander explained to the bartender that Long Now would be returning to the bar in twenty years — in time for the next rebuilding of the shrine. While the bartender was at first skeptical, Zander managed to convince him that they’d actually be back — spreading the word about Long Now along the way. That encounter also ended up inspiring Zander to create The Interval’s own bottle keep system, which can, of course, be used more frequently than once every two decades.

While 02023 marks the end of Zander’s time as Long Now’s Executive Director, his work with us is far from over. He will continue his work on The Clock of the Long Now as its installation continues. He will also continue to work on the Organizational Continuity Project, discovering the lessons behind the world’s long-lived institutions and pulling these lessons into a first of its kind book. He will also continue to be a dedicated member of Long Now’s community, a vital part of the culture that he has fostered over the last quarter century as we go into our next quarter century. Thank you, Zander.

Big trees, old trees, and especially big old trees have always been objects of reverence. From Athena’s sacred olive on the Acropolis to the unmistakable ginkgo leaf prevalent in Japanese art and fashion during the Edo period, our profound admiration for slow plants spans time and place as well as cultures and religions. At the same time, the utilization and indeed the desecration of ancient trees is a common feature of history. In the modern period, the American West, more than any other region, witnessed contradictory efforts to destroy and protect ancient conifers. Historian Jared Farmer reflects on our long-term relationships with long-lived trees, and considers the future of oldness on a rapidly changing planet.

Biosphere 2 was built in the late 01980s by the most unlikely group: a cast of creatives, a charismatic philosopher-king, a financier, theater nerds, and an amazing crew of engineers. The idea behind Biosphere 2 (Biosphere 1, of course, being the Earth) was to build a self-contained structure and set of systems that could test the idea of a self-contained space colony, albeit one that was anchored to the earth. In 01991, just four years after construction began, B2 was launched: a team of Eight “econauts” were sealed into the three-acre habitat, along with a Noah’s ark-load of life. Ostensibly, the challenge was simply to see if they could survive.

A team from Long Now arrived in Oracle, Arizona to tour Biosphere 2 on the evening of October 26, 02022, just as the sun was setting. We were there to investigate: to see if there were lessons that we could extract from B2 and apply at Long Now, specifically to the Clock of the Long Now. We all had done our homework and watched Spaceship Earth, the excellent new documentary that retells the B2 origin story. But nothing can really prepare one for the experience of encountering B2 in person.

Oracle, Arizona, is a long way from anywhere. The Sonoran Desert is a reasonable analog for the surface of Mars. And the ziggurats of steel and glass rise above the high plain like an American Giza.

The point of the original Biosphere 2 was bold, but straightforward enough. It was an experiment to see if it would be possible to create a self-contained ecosystem – one large enough to support the lives of the team inside. It was a space station, right here on Earth. And yet, right away, we had so many questions:

Like, why was there what seemed to be a vent at the top of the pyramid? Why install a vent on a closed system?

And what was that UFO-like object peeking out from behind the main pyramid?

These and other questions would have to wait until morning.

The next day, the team gathered for a tour given by John Adams, the Deputy Director and Chief Operations Officer of the facility. He explained that the tower structure that had so puzzled us the day before was, in fact, an observation tower. It was assumed that the original inhabitants of B2 would need a place to retreat to where they could observe “Biosphere 1” – the earth that they had left behind. The vent was installed to cool the glass pyramid, which, in reality, became a giant solar oven in the middle of the desert whenever the sun shined through it— which, in Arizona, was essentially every day. The vent was a striking reminder that B2 is rarely operated as a completely closed system. The ambition to study earth in a hermetically-sealed system has largely been supplanted by a more practical use for the facility: an ecological laboratory that can control more variables than nature allows. Under the auspices of its new owner, The University of Arizona, B2 is now mostly operated as a very large greenhouse, but it has the capability to do far more.

Biosphere 2’s 676,000-gallon “ocean” is the site of some rather significant science. It was here, in the living coral reef that lives under the faux ocean, that scientists proved that there was a direct connection between the increasing levels of CO2 in the atmosphere and decreasing coral calcification rates. There is currently an effort to breed and genetically engineer corals that can survive climate change – and those corals will be tested at B2 before being released into the open oceans.

The rainforest is also the site of important climate change research. Climate modelers have subjected it to drought, to floods, to higher-than-normal temperatures, and to atmospheres with higher-than-normal CO2 concentrations. The point is not to see what happens to the B2 rainforest per se, but rather to validate and calibrate the predictions that the climate models are pumping out about the fate of real rainforests during the coming Anthropocene.

B2’s former agricultural areas, the greenhouses where the original econauts grew their food, are now home to L.E.O.: the Landscape Evolution Observatory. L.E.O. has been called the first step in a new science of terraforming planets – which sounds exciting, but in practice boils down to watering sand and then watching that sand slowly turn into soil. Earth scientists have used B2 to watch dirt “grow” for eight years now. Next year they’re going to sprinkle some hay seeds over the newly-formed soil and see what happens.

The tour really got interesting when we were led into the life support system under Biosphere 2 – the so-called technosphere.

At the end of the tunnel is a giant variable volume chamber. It’s a “lung” that, when the biosphere is sealed up tight, fills and contracts with air. Remarkably, the sealed biosphere still loses less air by percentage volume than the International Space Station. When the sun rises, so does the lung’s 40-thousand-pound metal roof, which is attached to the walls by a flexible rubber membrane. And then when the sun sets, the roof settles back in place. Without the lung, B2 wouldn’t have lasted a single day – the windows would have shattered due to the changing atmospheric pressure inside.

As we wandered the grounds, it became apparent what an impressive feat of engineering Biosphere 2 was — and still is.

That evening, we gathered to consider what we saw at Biosphere 2. When B2 was first in the news back in 01991, it was hailed as a visionary piece of engineering which, by its very existence, asked us to understand ourselves differently. Biosphere 2 was the whole earth under glass, a miniature model of Spaceship Earth. We were meant to understand that while the econauts sealed inside were LARPing a trip across our solar system, the rest of us were not players in a play. We really were on board a ship, eight-thousand miles across and traveling at sixty thousand miles an hour around the sun – and the idiot lights on the life support system were, and still are, blinking red. B2 was a mammoth piece of engineering which embodied a philosophy, a point of view, a warning. And now? While B2 had been made scientifically useful, we all saw what was lost, too. Biosphere 2 has lost much of its original poetry and, with that, has largely fallen out of the conversation.

So, the question came back to us. How do we ensure the Clock of the Long Now doesn't suffer a similar fate?

At some point in the late fifth century, as the Western Roman empire fell, a group of Zoroastrian priests in Iran’s Fars Province lit a very special fire.

As the days passed, they kept the flame burning. Years became decades, and decades became centuries, with the fire moving between various locations, until it eventually ended up in the Yazd, a desert city around 600 km (373 miles) south-east of Tehran. In 01934, a new temple was built there to house it, where it continues to burn to this day. It’s one of only nine in the world – a flame that has been kept alive for more than 1,500 years.

This millennia-old Zoroastrian fire is an extraordinary act of long-minded maintenance – and one of many examples of long-term thinking in my new book The Long View: Why We Need to Transform How the World Sees Time (Wildfire, March 02023). What might we learn from it if we want to think with a longer perspective?

The Yazd temple that houses the 1,500-year-old fire today is situated on a busy street with cafés, clothing stores and a tourist information centre. Once you are inside the gate, however, the world outside fades into the background. Visitors encounter a peaceful garden, containing a round pool of water lined with benches and conical trees. Beyond that is a light-coloured, one-storey brick building, with a portico topped by the Zoroastrian ‘Faravahar’ symbol: a bird’s wings outstretched like an aeroplane viewed from above, with a holy male figure for a head.

Inside the building, the everlasting fire burns within a goblet. Several times a day, priests wearing all white tend the flames with a mixture of long-burning hardwood and sweet-scented softwood. Non-Zoroastrians are not allowed to go close, but visitors can view the chamber from the entrance hall. Looking at the fire through a tinted glass window, you can see the faint reflection of tourists peering in with their cameras, attempting to capture an image that will no doubt have faded or digitally decayed long before the flame goes out.

Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest faiths, and was founded approximately 3,500 years ago. It is based on the teachings of the Iranian prophet Zarathustra (also known as Zoroaster). In the Yazd fire temple, he is depicted in a painting with a bushy beard and long hair, a halo behind his head, carrying a staff and holding up a single finger, his eyes gazing upward.

With believers concentrated mainly in Iran and India, Zoroastrianism is much smaller than the major global religions: between 100,000-200,000 followers by some estimates. But over the centuries, Zoroastrian practices and writings have significantly influenced other faiths, as well as intersecting with the politics of states and empires. It gave Christianity the three wise men who attended the birth of Jesus – scholars reckon they were Zoroastrian priests – and supposedly helped to inspire Judaism’s theology of the afterlife, with the idea that what you do on Earth affects your fate after you die.

Zoroastrians have a particularly strong relationship with fire, which they see as a focus for ritual and contemplation. The ancient flames they tend are called Atash Bahrams, which means ‘victorious fire’. The fires are not worshipped, but when standing nearby, believers feel they are in the presence of the deity Ahura Mazdā. The flame can be symbolic of various things, expressing inspiration, compassion, truth, devotion, as well as continuity and change.

Atash Bahram fires are extraordinarily difficult to start, which explains why there are so few of them. The oldest fire in India, for example, has stayed burning for more than 1,000 years in a village called Udvada, north of Mumbai. To start it, Zoroastrian priests had to walk back to Iran to fetch a collection of sacred items called the alat – such as holy ash, a ring and the hair of a bull. En route they had to hide to avoid enemy armies and could not cross any rivers or seas, because fire and water cannot mix. It then took 14,000 hours of ritual. But here’s where it got really difficult: an Atash Bahram must be made by combining 16 different fires, taken from the homes of various professions such as a bricklayer, baker, warrior and artisan, plus the fire of a burning corpse and the fire of lightning. The latter fire is particularly difficult to source, because two Zoroastrians have to witness the lightning, and within a rainy storm hope that the strike sets something alight.

It is of course impossible to verify if the ancient fires have ever fizzled out once or twice. One can imagine that the chain has been disrupted by war, disease or natural disaster – and across 1,500 years there must have been many close calls. But the tending of the Atash Bahram flames is nonetheless one of the world’s longest-term commitments to a single act. And remarkably, it has endured through the medium of one of the world’s most ephemeral substances: a flame.

In The Long View, I write about how it’s possible to develop different “timeviews”: alternative perspectives of one’s place within the past, present and future to the dominant short-termist timeview of the modern age. The tending of the Zoroastrian flame is an example of what I call the continuity timeview: an approach to long-term stewardship defined by cross-generational baton-passing; a focus on making things last. (Another example would be the 20-year reconstruction cycle of the Grand Shrine in Ise, which Long Now’s Alexander Rose observed first-hand in 02013.)

So, what elements of the Zoroastrian faith led to this longevity, apart from pious dedication?

The everlasting flames show that it’s not necessary to leave behind something designed to last forever if you want to bridge across the long term. While Zoroastrianism certainly has its precious treasures, such as the alat used to start an Atash Bahram, arguably the faith’s most valuable heirlooms are instead their community practices and habits. It is these that define the continuity timeview.

Like so many faiths and cultures, Zoroastrianism emphasizes that there is a bond between generations. Through a shared act, by focusing attention on a fire that must be tended, the Zoroastrians pass a sacred responsibility forward. What makes this so powerful is that along the way, individuals personally benefit with status and other rewards.

But this is not the only long-minded lesson we might draw from the continuity timeview. Another crucial way that Zoroastrianism – or indeed any successful religion – passes ideas across time is via the power of ritual.

The performance of ritual can be traced into human prehistory. But as societies grew larger, the more routine community-building rituals of faith came into their own, such as prayer, music, tending flames, ceremonies and more. According to the anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse at the University of Oxford, rituals helped to foster the trust, cooperation and cohesion that enabled civilizations to flourish: a social glue that bound people together across space and time.

Rituals helped to spread the idea of what a ‘good’ citizen should be, gluing together heterogenous societies. Every time a prayer was recited or a ceremony performed, it signalled a commitment to shared moral beliefs and collective goals among disparate people. As the Islamic scholar Ibn Khaldun observed in the fourteenth century, rituals fostered asabiyah, which in Arabic roughly means ‘social cohesion’, transporting solidarity beyond direct kinship to a national scale.

Over time, ritual practices became ever-more embedded in the major organized religions – Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism. They are all different in detail, but have much in common.

Many involve synchrony or display, such as the Islamic call to prayer or the Christian singing of hymns. Food makes a regular appearance, such as in Catholic Communion, or the Buddhist preparation of meals to feed hungry ghosts (a neglected spirit or ancestor). Fire or burning incense is also seen across countries and faiths – the lighting of candles to mark the start of the shabbat, or the diya lamps during Diwali. And so is cleansing, such as the various procedures followed before entering temples, or the Hindu practice of bathing the body in holy rivers before festivals.

For the Zoroastrians, tending the fire is a ritual in itself, and the locus for regular ceremonies to mark occasions, called jashan, which involve implements such as fruits, nuts and wheat pudding in metallic trays placed on a white sheet with milk, wine and flowers, led by a priest called a zoatar, while another person looks after the fire: an atravakshi.

Plenty of rituals have no obvious reason to be performed in the specific way that they are, and one culture’s ritual norm can raise eyebrows in another. But the detail does not matter. It’s about the ideas they carry, and the community behaviours they help to foster. As well as encouraging repetition and remembrance, these rituals are a way of forging a relationship with longer-term time, marking beginnings and endings, as well as a connection with ancestors. Rituals therefore are a human behaviour by which ideas can travel across decades and centuries.

If a non-believer or secular organization were hoping to become more long-minded and create ideas that endure, they might do well to ask: what rituals and traditions bring their communities together?

Some rationally minded sceptics might be reluctant to participate in a spiritual practice, but not all rituals involve deities or worship.

Recently, I asked Nicholas Paul Brysiewicz, the director of strategy at the Long Now Foundation, how he thinks about ‘long rituals’ within the organisation. He cited the obvious events like the monthly seminars the foundation holds, inviting speakers to talk about long-minded research or writing, as well as more casual meetings for the broader Long Now community at The Interval, Long Now's office, bar, and gathering-place in San Francisco, California. But there are also less frequent traditions that Brysiewicz and his colleagues follow: for example, the team makes regular camping “pilgrimages” to the original site of the 10,000 Year Clock project in Eastern Nevada. Then there’s the annual Lost Landscapes of San Francisco event in December with the Prelinger Library, he says, and the concomitant Winter Party for members and friends.

Through these activities, Brysiewicz and his colleagues are participating in the same kind of shared acts and ritual practices that have connected people for centuries – bearing witness to oration, finding fellowship in communal meals, pilgrimage, and honouring important sites.

If you think about it, your life is probably already packed with rituals: national holidays, sports events, family traditions, and far more. They can be celebratory, such as a song sung over a birthday cake, or sombre, such as a minute’s silence to remember the dead. But one question to ask yourself might be: which ones are promoting the principles of maintenance and stewardship?

Whether it is the commitment to a single act, such as tending the everlasting Zoroastrian flame, or participation in a chain of acts, observing rituals connects us across space and time. They are one of the most long-minded habits we have.

Richard Fisher is the author of The Long View: Why We Need to Transform How the World Sees Time (Wildfire), which was published in the UK and other territories on 30 March 02023. He writes the newsletter The Long View: A Field Guide.

Imminent climate catastrophe. An unending pandemic. Rampant authoritarianism. Unceasing incarceration in the United States. Half of the United States unable to afford one $400 emergency. Grossly concentrated global wealth and 1.7 billion workers in the world residing in countries where inflation outpaces wages. A significant increase in the number of people going hungry across the globe. Some 574 million people worldwide expected to endure extreme poverty by 02030 if trends continue.

Interrelated crises abound, and the effects are felt not just in one country or a couple of countries, but across the planet. To address the crises, then, we probably ought not to take an individual nation-state as the primary unit of analysis or as the key site for transformative action.

If we operate under the ostensibly reasonable assumption that existing crises reflect sometimes difficult-to-detect historical developments, then we also ought to concern ourselves with the longue durée. The French historian Fernand Braudel and the Annales School, a tradition rooted in the study of long duration social history, popularized the concept.

“My understanding of the longue durée is that it's something that takes place over many, many centuries, if not millennia,” Omer Awass, an associate professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at American Islamic College.

Awass is what you might call a world-systems theorist.

At the core of world-systems thinking is the need to pay attention to and glean insights from the slow-moving historical changes that occur over the long-term, over what world-systems scholars refer to and study as the longue durée, so as to throw light on the chaotic, rapidly changing reality we live in now.

Looking at the longue durée with a world-systems lens reveals the flawed contours of our social order, like the economic imperative to subordinate the concerns of most human beings to institutionalized pressures to commodify, grow, maximize profit and accumulate capital while concentrating influence and decision-making power.

Taking the world-system, rather than a nation-state or conventional geopolitics, as the primary unit of analysis clarifies why previous attempts to realize lasting, uplifting transformative change have too often proven largely if not wholly ineffective — and in some instances disastrous. The aims of national liberation struggles and revolutionary efforts to attain and exercise state power to drastically improve people’s lives never fully materialized or endured, world-systems analysis informs us, because of the larger systemic forces at work.

Immanuel Wallerstein, perhaps the most prominent and prolific proponent of world-systems analysis, suggested that those systemic forces include the imperative to accumulate capital. They include the disparate power relations between nation-states that have expanded capital accumulation. Those features of the system prioritize constant production of surplus at the expense of people disadvantaged by existing arrangements and at the increased risk of exacerbating existential crises, ecological and otherwise.

Recalibrating our focus to the structures extending beyond and influencing international as well as intra-national relations helps us grasp why interventions at national scales likely won’t do more than provide partial palliatives for the deeper ills of the world, sans fundamental shifts in how we organize and maintain our interconnected lives.

When it comes to understanding the crises as well as the opportunities we face today, Wallerstein’s analysis also offers an apropos insight, or a prophetic prognostication, if we wish to entertain his theory with greater skepticism. Prior to his death in 02019, Wallerstein claimed that, since at least the 01970s, our modern world-system has been in a period of structural crisis. For him and for many world-systems scholars, the upturns and downturns of the capitalist world-economy that the system has cycled through for centuries, perhaps longer, have pushed it further and further away from equilibrium, to a point of no return.

“The primary characteristic of a structural crisis is chaos,” Wallerstein wrote in an essay from 02011. “Chaos is not a situation of totally random happenings. It is a situation of rapid and constant fluctuations in all the parameters of the historical system. This includes not only the world-economy, the inter-state system, and cultural-ideological currents, but also the availability of life resources, climatic conditions, and pandemics.”

Those wild fluctuations emerge from and compound the crises that surround us.

“Because the fluctuations are so wild, there is little pressure to return to equilibrium,” Wallerstein argued in a 02010 essay, explaining our predicament. “During the long, ‘normal’ lifetime of the system, such pressure was the reason why extensive social mobilizations — so-called ‘revolutions’ — had always been limited in their effects. But when the system is far from equilibrium, the opposite can happen—small social mobilizations can have very great repercussions, what complexity science refers to as the ‘butterfly effect’. We might also call it the moment when political agency prevails over structural determinism.”

A world-systems perspective on the formation and long-term transformation of enduring social arrangements can help us understand how social movements and perhaps our own personal actions and interactions might tilt the balance to bring about a better successor system, or at least give us a greater understanding of what it would take to improve human lives during these tumultuous times.

If capitalism and the somewhat synonymous modern world-system that has sustained it are ending sooner rather than later, per Wallerstein’s view, or even if we just wish to address the underlying sources of our interrelated problems, world-systems analysis offers unique insight into what not to keep doing. It helps identify the repeated large-scale patterns that must be discontinued and displaced to build a better world.

A brief genealogy of system history informed by the thoughts of those using world-systems theory should help hone that perspective.

Not all world-systems thinkers have understood the longue durée of the existing system in the same way. While Wallerstein believed it’s a 500-year-old system that’s coming to an end, what if the system dates back much farther — say, 5,000 years? A different perspective on its origins can alter our understanding of how it may end or what successor system(s) arise in its wake. At the same time, extending the longue durée view of the system could affect our grasp of its fundamental qualities, what must be transformed within it, and what social arrangements are possible beyond it.

Andre Gunder Frank, one of Wallerstein’s friends and contemporaries, took a more continuationist view of system history. Frank, along with Barry Gills, claimed enduring features of the system, like constant capital accumulation, date back several millennia and occurred throughout the world system via investment in agriculture, livestock, industry, transport, commerce, militaries and other means. In “The World System: 500 Years or 5,000?,” Frank and Gills suggested the motor force of capital accumulation and a shifting hierarchy of center-periphery complexes dates back more than just a few centuries. Wallerstein and another first generation world-systems scholar, Samir Amin, undervalued the significance of trade and market activity in the ancient world, causing them to overlook the role certain people or areas played in the development of the “world political-economic system” that’s displayed the same “structural patterns and processes for at least 5,000 years,” Frank and Gills explained.

They saw capital being accumulated, surplus being generated, and different regions benefiting disproportionately from the transfer of that surplus way before the 16th century European point that many sources, including Wallerstein, place it at. Both perspectives theorize a capitalist system that predates the industrial capitalism that Karl Marx critiqued in the nineteenth century when he analyzed the production of capital that occurred under harsh conditions in England’s factories.

If Wallerstein, Marx, and others identified qualitative shifts in social relations that became significant more recently than 5,000 years ago, adopting a continuationist view of history with an insistence on seeing enduring features of the system as several-millennia-old could make it difficult for people to imagine other possible arrangements. The late David Graeber, an anthropologist and one of the organizers of the initial Occupy Wall Street encampment in New York City circa 02011, suggested as much in a journal article which called into question the tendency to see shades of capitalism everywhere.

Graeber might have been right about the challenges associated with imagining and realizing better worlds when we privilege the longue durée over interest in the experience of social relations, focusing on the cumulative production of surplus and capital over the production of people. Yet Frank and Gills’ millennia-encompassing view of developing systemic interactions also alerts us to overlooked processes operating on grander timescales. That view brings into focus enduring arrangements responsible for disparities and sociological phenomena that we would be foolish to tie solely to post-01800 institutions.

Moreover, dating the origins of the system back several millennia might ironically even help us imagine how socioeconomic relations might be otherwise, à la Graeber.

A closer look at the work of David Wilkinson, a professor of political science at UCLA who contributed a chapter — “Civilizations, Cores, World Economies, And Oikumenes” — to the aforementioned Frank and Gills text reveals some of those imaginaries. Wilkinson opted for the framework of civilizations, which he referred to as vast social entities that “transcend the geographical boundaries of national, state, economic, linguistic, cultural, or religious groups.”

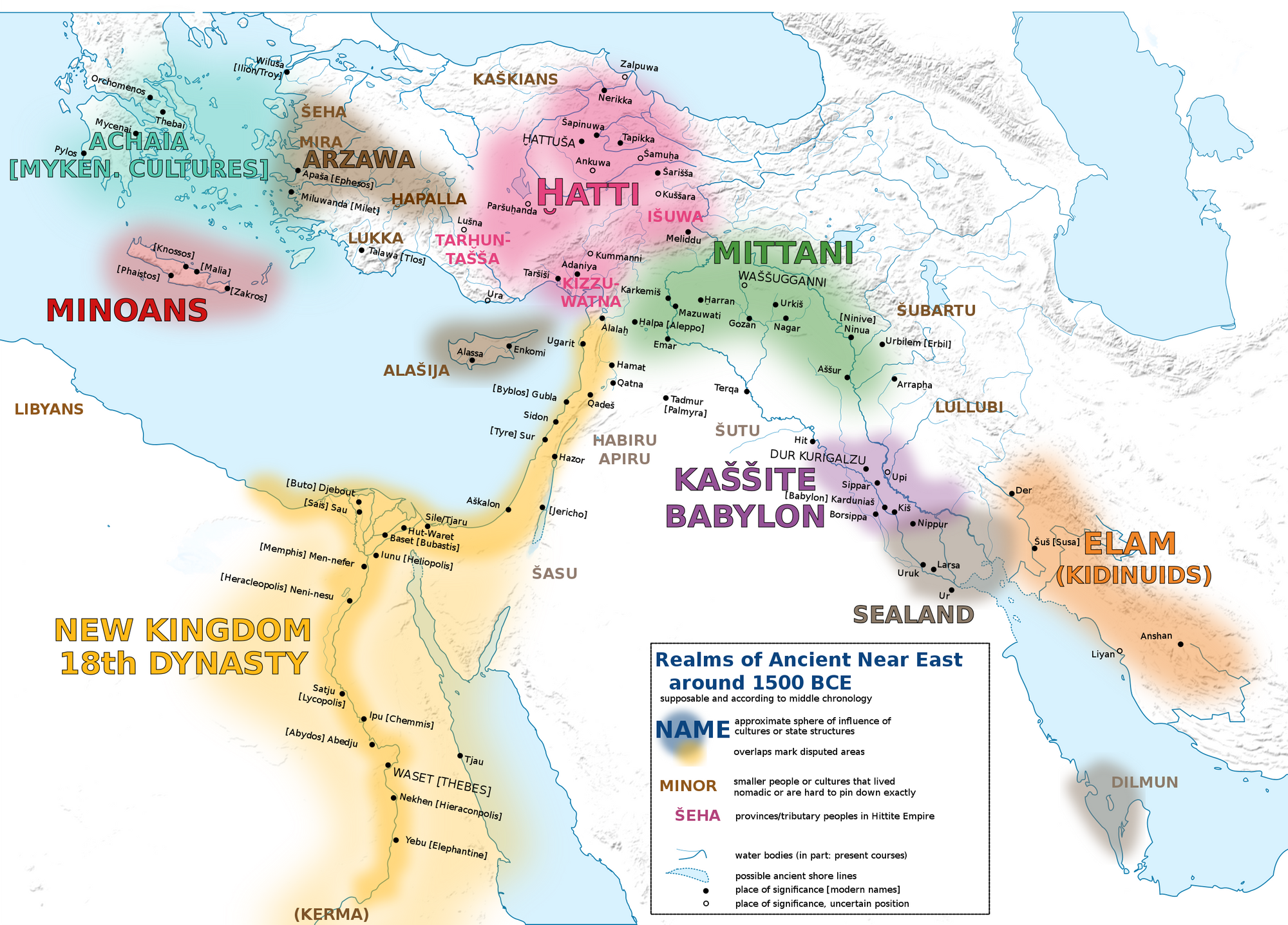

In Wilkinson’s estimation, several civilizations coexisted up until the 19th century, but today there’s a single, global civilization. This “Central Civilization” is a descendant of a civilization that emerged around 01500 BC when Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations collided and fused. Over the next 3,500 years, that civilization “then expanded over the entire planet and absorbed, on unequal terms, all other previously independent civilizations.”

Some civilizational mergers have involved groups seizing control over and incorporating other groups. But the linking of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations in the second millennium BC was an “atypical” and “egalitarian” coming together that, if Wilkinson has his history right, formed “a new joint network-entity” and differed from many future agglomerations involving annexation of one by civilization by another.

His somewhat idiosyncratic version of world-systems analysis and assessment of the longue durée frames the origins of what would much later become our globe-encircling “Central Civilization” as a fairly equitable encounter, on a certain level.

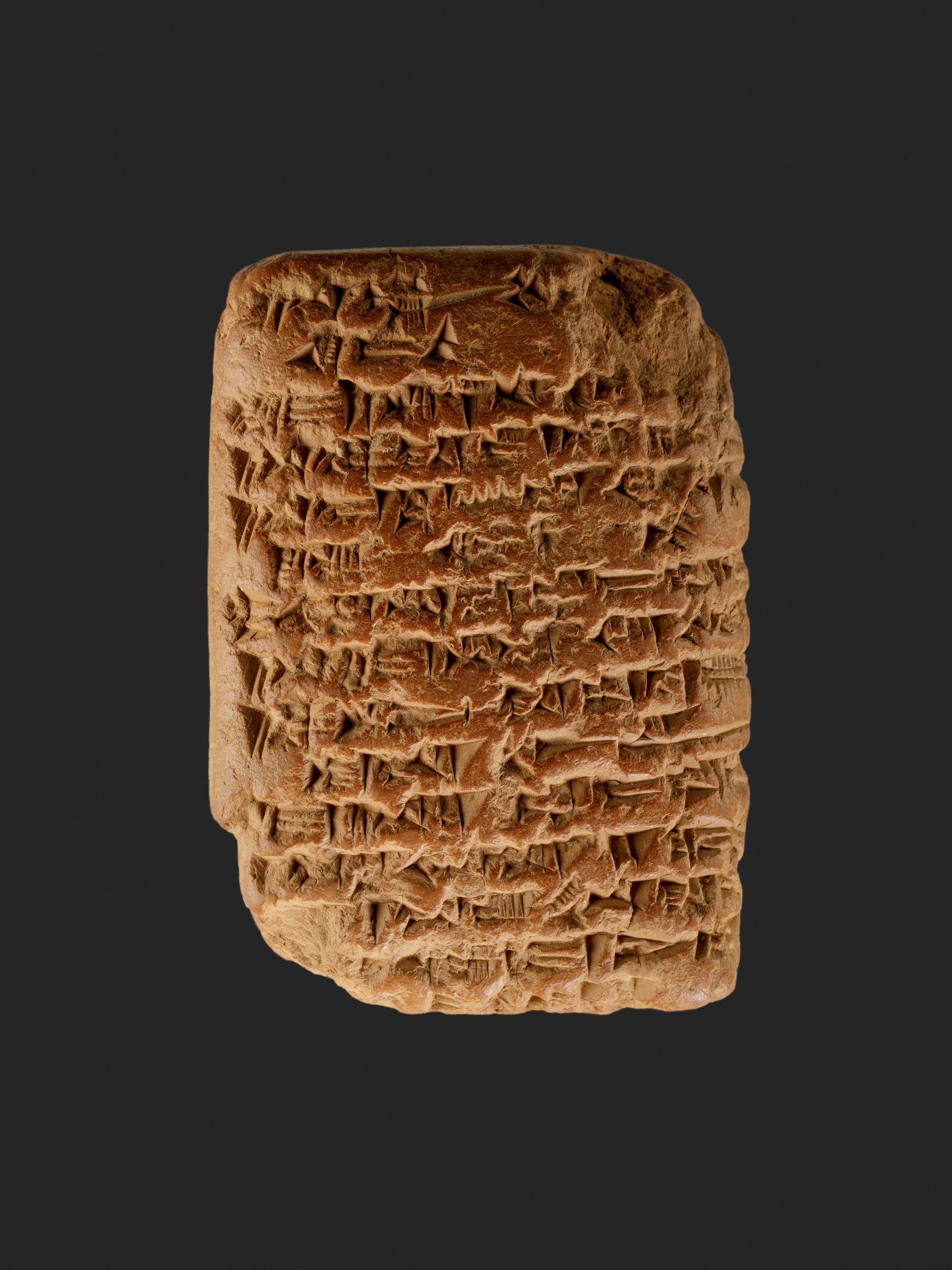

“The connection was made and maintained through mutually beneficial trade; politico-military independence and equality were preserved through the stalemating of imperialist war and the frustration of conquest,” Wilkinson explained. Records from Armana referring to gold from Egypt and royal daughters from states in Southwest Asia indicate they maintained exchange relations through a kind of luxury trade that nevertheless exacted a human toll.

The historical possibility of forging relations without domination can be seen as a source of hope — though these ancient civilizations came together via millennia-old realpolitik rather than humanitarian impulses.

As Wilkinson explained it, the merger of the two separate systems into one came as Egyptians aimed “to maintain multipolarity in southwest Asia,” and thus began treating the Mitanni kingdom in Mesopotamia not “as an external target for loot nor a potential subaltern to conquer, but as a useful check to balance the rising power of the Hittites, themselves far out of Egypt’s direct imperial reach.”

Over millennia, the network that formed at the intersection of Asia and Africa came to encompass networks to the west in Europe, the Americas, the western part of the African continent and in south and east Asia placing it, in certain respects, at the center of the world stage.

Christopher Chase-Dunn, sociologist and director of the Institute for Research on World-Systems at the University of California, Riverside, sees the existing system as more or less coeval with what’s considered the ascendance of the West. He follows the view of first-generation world-systems scholar Giovanni Arrighi, who claimed the modern capitalist world-system formed when Genoa and Portugal entered an alliance in the 15th century.

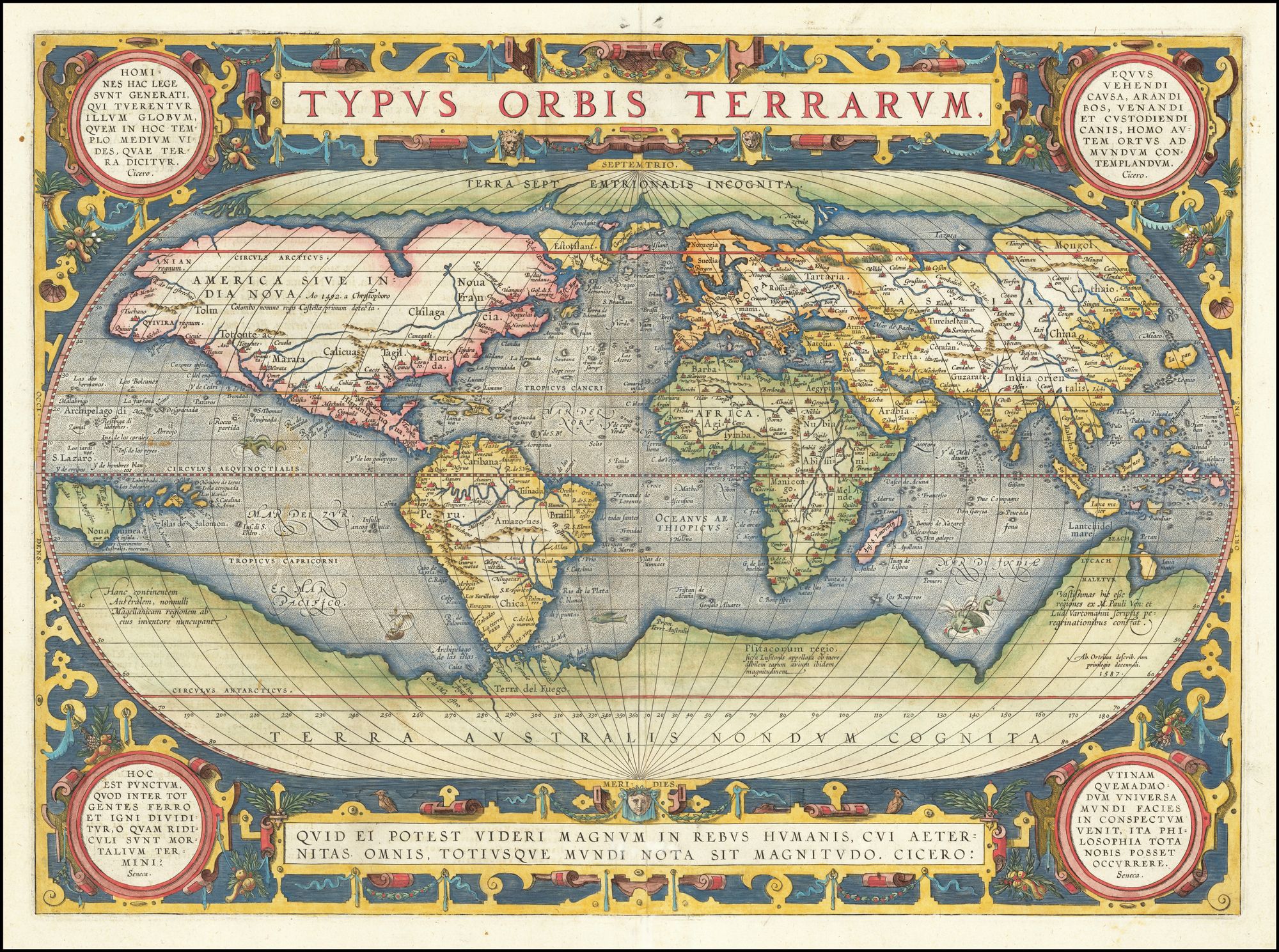

In a similar vein, Wallerstein argued in “The Modern World-System I,” that a “European world-economy” came into being in the late 15th and early 16th century. As a new “economic but not a political entity,” in his words, “unlike empires, city-states and nation-states,” within it, this social system was a “world” because it exceeded “juridically-defined political unit[s],” and a “world-economy” because economic relations formed the basis of connection that propelled its subsequent expansion across the globe.

Aviva Chomsky, a professor of history at Salem State University, explained how in a course she teaches at SSU, “Colonialism and the Making of the Modern World,” she draws on the late world-system scholar Janet Abu-Lughod’s “Before European Hegemony,” to explore the “Afro-Eurasian system of interlocking trade/communication spheres from East Asia to the Mediterranean/North Africa” that antedated 01492.

Similar to the Egypt-Mesopotamia partnering at the origin of the “Central Civilization,” in Wilkinson’s account, regions in that Afro-Eurasian system about 500 years ago participated, per Chomsky, with relative parity. But, she stresses, that didn’t equate to egalitarianism within them. To one degree or another, they were all “based on systems of forced/dispossessed labor, taxation,” which were, “extracted from the poor to serve the power, leisure, and consumption of elites.”

With the late-15th century rise of European hegemony — in other words, with the continent’s disproportionate influence and authority over other regions — there also arose “an Atlantic world system in which Europe, led by Spain and Portugal, conquers the Americas and develops the transatlantic slave trade, with devastating consequences for the peoples of Africa and the Americas,” Chomsky said.

World-systems scholars use language of “core” and “periphery” zones and processes, referring to the relations of operation, leverage, and control that benefit some nation-states at the expense of others. Certain nation-states or similar entities can at times obtain control over the system at large, and they call this dominance hegemony. Its full realization is considered relatively rare. Wallerstein, Chase-Dunn and others believe the United Provinces of the Netherlands became a hegemonic core power circa the 17th century, as they achieved overwhelming trading power in the fledgling market economy.

Two other powers are thought to have achieved serious hegemonic status over the longue durée of our current, now crisis-riddled system. Their hegemony and hegemonic declines coincided with significant changes in the workings of the world.

As northern European nations started to take over the slave trade and extend colonization “into the peripheries of Asia,” the Spanish and Portuguese empires declined, according to Chomsky’s reading. Then, “the shift accelerates in the [01800s] as a new ‘world system’ emerges,” the newly “independent United States joins with (primarily) Britain, France, [and] the Netherlands to establish colonial hegemony in the Americas, Africa, and much of Asia.”

Awass said in a late December 02022 interview that core regions intervened in the periphery in a direct way during the colonial period. “In a sense, they intervene[d] directly by taking over many countries or getting capitulations from countries that [they] could not take over directly, like the Ottoman Empire, or the Chinese Empire, Japan and Thailand, for example,” he said.

A key factor in this system was the exploitation of the natural resources of the periphery by the core. During this period, non-European industrial production suffered, Chomsky explained, as the other regions succumbed to pressures to export raw materials like cotton, copper, coal, tin, petroleum, and palm oil to Europe, as well as to the United States.

As it assumed a hegemonic position within the world-system in the 19th century, Britain became home to the expansive factory labor, employment, and production that horrified and fascinated thinkers like Marx, who wrote extensively about British manufacturing as he tried to understand and explain the engine of the system.

Britain’s dominance waned by the 20th century when a new world power attained what Wallerstein considered the most “extensive and total” exercise of hegemony and established conditions for what “promises to be the swiftest and most total” decline.

Most anyone who uses world-systems theory, and many who don’t, agree that after World War II, the United States emerged as a hegemonic power.

In this era, as Chomsky framed it, decolonized people achieved “nominal political independence” but faced overwhelming resistance in a struggle for an alternative economic order. The Cold War helped justify the United States in crushing attempts to redress the system and ex-colonial powers maintained “unequal exchange” and retained control of trade and financial institutions at the international level.

Awass has tried to model the world-system as a “Global Power-Field,” or GPF, drawing attention to important forces that covertly perpetuate and reshape global relations of control and subordination. His concept of “nonlocality” highlights how after decolonization the reshaping of the field made it so core powers no longer needed to remain present in peripheral regions to control or exploit them.

“It was these institutions and the rules of this new global field that everybody now had to play by because they joined the international nation-state system and all of the different global bodies, like the United Nations, which was an acknowledgment of this international nation-state system, and they set up the rules of the game, and just let the rules operate to their favor,” he said.

The supreme hegemony the United States exercised did not last long. Wallerstein held that as the most expansive phase in a cycle of the capitalist world-economy gave way to a downturn, it coincided with the commencement of American hegemonic decline. It was no accident, in his view, that social movements and popular revolts reflected and expressed world-historical changes around that time.

“He was at Columbia University when the student movement in 01968 erupted,” notes David Martinez, a documentarian at work on a project about Wallerstein’s ideas, later adding: “He was a young professor at Columbia, and he was actually on the committee of teachers to work with the students. That's when he saw that the movements of 01968 were of world historical importance.”

Various uprisings converged in what world-system theorists, following Wallerstein, call the 01968 “world revolution,” which Wallerstein thought foregrounded new developments in the analysis and orientation of anti-systemic movements.

Striking workers and students in Paris almost ushered in another French revolution that year in May. Come August, Soviet-directed forces invaded Czechoslovakia to crush the “Prague Spring” movement that tried to create “socialism with a human face.” In the United States, organizations like Students for a Democratic Society and the Black Panther Party influenced communities as well as popular culture, and the demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago put police violence on full display following a solid year of protests and riots that engulfed cities throughout the country. Authorities also shot into a crowd of thousands of student activists in the streets of Mexico City that October just before the start of the Olympics.

Intensified resistance to US aggression in Vietnam, punctuated by the Tet Offensive that kicked off the year of “world revolution,” revealed new limits on the reigning superpower’s military might, portending a waning of hegemony. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union faced scrutiny for colluding with the United States in Cold War maintenance of geopolitical power. Organizers called into question the strategy of seizing state power as the necessary initial step in trying to improve conditions and world relations, and they emphasized the oft-ignored aims and concerns of people marginalized because of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.

Liberalism entailed an assumption about the possibilities for continued human progress and uplift within the established hegemonic order, but the revolutionary upheaval of 01968 ended the tenuous triumph of the “centrist liberalism” that had dominated, Wallerstein thought, “for a good hundred-odd years.”

The displacement of that previously dominant ideology epitomized and propelled what Wallerstein conceived of as the system’s ongoing phase of structural crisis. Yet these last few decades of crises might also foretell new possibilities for the next turn of the world-system.

Andre Gunder Frank understood the coming crisis as denoting both “danger and opportunity.” In his 01998 book, “ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age,” he forecast a coming period wherein East Asia would regain its preeminent world-economic position, and he claimed that “a time of crisis, especially for the previously best-placed part of the world economy/system, also opens a window of opportunity for some — not all! — more peripherally or marginally placed ones to improve their own position within the system as a whole.”

Indeed, the impetus and reverberations of the “world revolution” in 01968 foregrounded the concerns of the previously peripheral and marginal, at least at the cultural or ideological level, in Wallerstein’s reading. Those movements intimated another possible world(-system) with different popular values. They prefigured future and indeed current social movements, but they also elicited an enduring reactionary response.

When social upheavals ensued and crises emerged around 01970, major players in the global system made moves to retain their dominance that arguably initiated or accelerated all those previously mentioned trends.

Awass has written about the role of U.S. “dollar hegemony” post-WWII. The United States’ formal replacement of the gold standard with the dollar standard in early 01970s could have brought about a decisive end to American hegemony, as states outside of the Western core began to grumble about the dollar’s place as a fiat currency. In Awass’ analysis, the United States’ maintenance of hegemony was achieved by striking a deal in 01974 with Saudi Arabia, offering the regime protection. In exchange, the kingdom used its standing as the quasi-official leader of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, pressuring them to accept only the dollar in exchange for oil, which allowed the United States to continue to leverage power through the monetary system.

In his article, Awass pointed to US.-imposed sanctions on Iran as further evidence of a core power trying to maintain control with little regard for human consequences, though his piece focused on macro-modeling.

“I didn't highlight those dimensions of how it worked at the micro level of Iran, for example, on the second levels of the sort of sanctions that were taking place there, but for God's [sake], I mean, people can't even afford medicine,” he said.

The collapse of the Soviet Union near the close of the 20th century didn’t exactly spell “The End of History,” but it did temporarily reinforce the power of a descending hegemon in a volatile world order.

“After 01989 there is really no check at all left on US hegemony,” Chomsky added, “and the neoliberal order is imposed full-scale, with the Third World subject to structural adjustment, the dismantling of the social welfare state at home and abroad, deindustrialization of the core and maquiladorization, extractivism, tourism, and call centers as the new development strategies for the periphery. Meanwhile the impact of the industrial project comes home to roost with climate chaos, mass migration, [xenophobia] and hardened borders.”

Following Wallerstein’s analysis, the cost of the waste associated with economic production can no longer be so easily externalized by the businesses and industries producing it, given greater popular pressure to challenge pressing ecological injustices and curb the climate disruption driven by those externalities of capitalist production. That pressure further raises the cost of doing business within the existing system, which in turn contributes to the chaotic downturn and fluctuations characteristic of structural crisis.

For Chase-Dunn, the ongoing “contradictions of capitalism and decline of US hegemony” could contribute to “further renewal of inter-state warfare,” climate crises, and possible “deglobalization” of the global economy – possibly leading to collapse of the financial system in the next few decades.

To pursue a facet of Wallerstein’s work that seems especially urgent now, Chase-Dunn, along with Rebecca Alvarez, put together a proposal for a political vehicle that could combine the participatory elements of horizontal organization, free from top-down authority, together with a transnational steering structure. Via “The Vessel,” affinity groups and local communities could share the results of their work, facilitate collaboration, formulate visions for social change, determine preferable strategies as well as tactics, and coordinate global collective action, campaigns, and mobilizations through a delegated council. Perhaps this organizational ark or ship is capable of navigating through the proverbial flood ready to wash out a perturbed world-system during whatever kind of transitional period we’re in at present, provides one possible antidote to the preponderance of influence exercised among small slivers of the population within the confines of the interstate nexus and capitalist world-economy.

People could also carve out and coordinate a network of physical and digital spaces where care and cooperative decision-making gives everyone the ability to influence institutions, policies, relations and actions that affect them. Those spaces might embody and popularize values that could prevail over the outmoded ones embedded in the capitalist world-economy.

Similarly, Awass mentioned “courage,” “gumption” and “moral cultivation” as likely prerequisites for effective political action going forward. He acknowledged setbacks in struggle, like the crushing of the Arab Spring movement and the overturning of many of its achievements. “I think there perhaps are some positive signs of increasing global solidarity,” he qualified, referencing international climate justice activism while also lamenting forces that tend to circumvent such efforts.

Aviva Chomsky in turn recommended a piece by Jason Hickel on de-growth and anti-colonial politics as a source of ideas for action.

“In terms of what we can [or should] do now, I think that understanding the relationship between racism, colonialism, and climate chaos leads us to remaking the global industrial order with [degrowth] in the global north as a component of reparations for the ongoing damages,” she shared.