An interview with Prof Antonio Diéguez Lucena, professor of Logic and Philosophy of Science at the University of Málaga, Spain. Here he speaks of his research into the philosophy of biology and technology.

“Analytic philosophy gradually substitutes an ersatz conception of formalized ‘rigor’ in the stead of the close examination of applicational complexity.”

In the following guest post, Mark Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, argues that a kind of rigor that helped philosophy serve a valuable role in scientific inquiry has, in a sense, gone wild, tempting philosophers to the fruitless task of trying to understand the world from the armchair.

This is the third in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

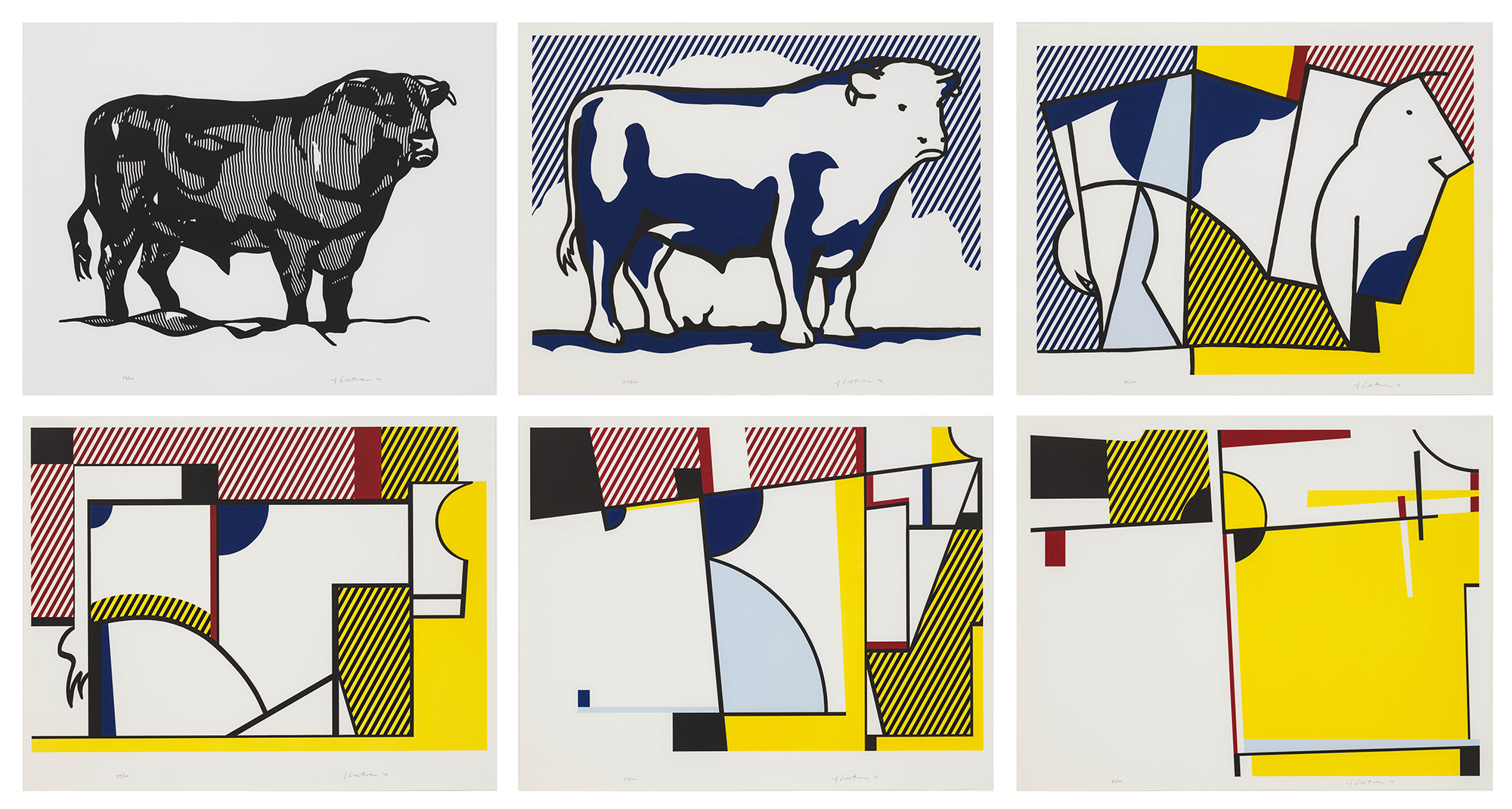

[Roy Lichtenstein, “Bull Profile Series”]

In the course of attempting to correlate some recent advances in effective modeling with venerable issues in the philosophy of science in a new book (Imitation of Rigor), I realized that under the banner of “formal metaphysics,” recent analytic philosophy has forgotten many of the motivational considerations that had originally propelled the movement forward. I have also found that like-minded colleagues have been similarly puzzled by this paradoxical developmental arc. The editor of Daily Nous has kindly invited me to sketch my own diagnosis of the factors responsible for this thematic amnesia, in the hopes that these musings might inspire alternative forms of reflective appraisal.

Let us return to beginnings. Although the late nineteenth century is often characterized as a staid period intellectually, it actually served as a cauldron of radical reconceptualization within science and mathematics, in which familiar subjects became strongly invigorated through the application of unexpected conceptual adjustments. These transformative innovations were often resisted by the dogmatic metaphysicians of the time on the grounds that the innovations allegedly violated sundry a priori strictures with respect to causation, “substance” and mathematical certainty. In defensive response, physicists and mathematicians eventually determined that they could placate the “howls of the Boeotians” (Gauss) if their novel proposals were accommodated within axiomatic frameworks able to fix precisely how their novel notions should be utilized. The unproblematic “implicit definability” provided within these axiomatic containers should then alleviate any a priori doubts with respect to the coherence of the novel conceptualizations. At the same time, these same scientists realized that explicit formulation within an axiomatic framework can also serve as an effective tool for ferreting out the subtle doctrinal transitions that were tacitly responsible for the substantive crises in rigor that had bedeviled the period.

Pursuant to both objectives, in 1894 the physicist Heinrich Hertz attempted to frame a sophisticated axiomatics to mend the disconnected applicational threads that he correctly identified as compromising the effectiveness of classical mechanics in his time. Unlike his logical positivist successors, Hertz did not dismiss terminologies like “force” and “cause” out of hand as corruptly “metaphysical,” but merely suggested that they represent otherwise useful vocabularies that “have accumulated around themselves more relations than can be completely reconciled with one another” (through these penetrating diagnostic insights, Hertz emerges as the central figure within my book). As long as “force” and “cause” remain encrusted with divergent proclivities of this unacknowledged character, methodological strictures naively founded upon the armchair “intuitions” that we immediately associate with these words are likely to discourage the application of more helpful forms of conceptual innovation through their comparative unfamiliarity.

There is no doubt that parallel developments within symbolic logic sharpened these initial axiomatic inclinations in vital ways that have significantly clarified a wide range of murky conceptual issues within both mathematics and physics. However, as frequently happens with an admired tool, the value of a proposed axiomatization depends entirely upon the skills and insights of the workers who employ it. A superficially formalized housing in itself guarantees nothing. Indeed, the annals of pseudo-science are profusely populated with self-proclaimed geniuses who fancy that they can easily “out-Newton Newton” simply by costuming their ill-considered proposals within the haberdashery of axiomatic presentation (cf., Martin Gardner’s delightful Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science).

Inspired by Hertz and Hilbert, the logical empiricists subsequently decided that the inherent confusions of metaphysical thought could be eliminated once and for all by demanding that any acceptable parcel of scientific theorizing must eventually submit to “regimentation” (Quine’s term) within a first order logical framework, possibly supplemented with a few additional varieties of causal or modal appeal. As just noted, Hertz himself did not regard “force” as inherently “metaphysical” in this same manner, but simply that it comprised a potentially misleading source of intuitions to rely upon in attempting to augur the methodological requirements of an advancing science.

Over analytic philosophy’s subsequent career, these logical empiricist expectations with respect to axiomatic regimentation gradually solidified into an agglomeration of strictures upon acceptable conceptualization that have allowed philosophers to criticize rival points of view as “unscientific” through their failure to conform to favored patterns of explanatory regimentation. I have labelled these logistical predilections as the “Theory T syndrome” in other writings.

A canonical illustration is provided by the methodological gauntlet that Donald Davidson thrusts before his opponents in “Actions, Reasons and Causes”:

One way we can explain an event is by placing it in the context of its cause; cause and effect form the sort of pattern that explains the effect, in a sense of “explain” that we understand as well as any. If reason and action illustrate a different pattern of explanation, that pattern must be identified.

In my estimation, this passage supplies a classic illustration of Theory T-inspired certitude. In fact, a Hertz-like survey of mechanical practice reveals many natural applications of the term “cause” that fail to conform to Davidson’s methodological reprimands.

As a result, “regimented theory” presumptions of a confident “Theory T” character equip such critics with a formalist reentry ticket that allows armchair speculation to creep back into the philosophical arena with sparse attention to the real life complexities of effective concept employment. Once again we witness the same dependencies upon a limited range of potentially misleading examples (“Johnny’s baseball caused the window to break”), rather than vigorous attempts to unravel the entangled puzzlements that naturally attach to a confusing word like “cause,” occasioned by the same developmental processes that make “force” gather a good deal of moss as it rolls forward through its various modes of practical application. Imitation of Rigor attempts to identify some of the attendant vegetation that likewise attaches to “cause” in a bit more detail.

As a result, a methodological tactic (axiomatic encapsulation) that was originally championed in the spirit of encouraging conceptual diversity eventually develops into a schema that favors methodological complacency with respect to the real life issues of productive concept formation. In doing so, analytic philosophy gradually substitutes an ersatz conception of formalized “rigor” in the stead of the close examination of applicational complexity that distinguishes Hertz’ original investigation of “force”’s puzzling behaviors (an enterprise that I regard as a paragon of philosophical “rigor” operating at its diagnostic best). Such is the lesson from developmental history that I attempted to distill within Imitation of Rigor (whose contents have been ably summarized within a recent review by Katherine Brading in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews).

But Davidson and Quine scarcely qualified as warm friends of metaphysical endeavor. The modern adherents of “formal metaphysics” have continued to embrace most of their “Theory T” structural expectations while simultaneously rejecting positivist doubts with respect to the conceptual unacceptability of the vocabularies that we naturally employ when we wonder about how the actual composition of the external world relates to the claims that we make about it. I agree that such questions represent legitimate forms of intellectual concern, but their investigation demands a close study of the variegated conceptual instruments that we actually employ within productive science. But “formal metaphysics” typically eschews the spadework required and rests its conclusions upon Theory T -inspired portraits of scientific method.

Indeed, writers such as David Lewis and Ted Sider commonly defend their formal proposals as simply “theories within metaphysics” that organize their favored armchair intuitions in a manner in which temporary infelicities can always be pardoned as useful “idealizations” in the same provisional manner in which classical physics allegedly justifies its temporary appeals to “point masses” (another faulty dictum with respect to actual practice in my opinion).

These “Theory T” considerations alone can’t fully explicate the unabashed return to armchair speculation that is characteristic of contemporary effort within “formal metaphysics.” I have subsequently wondered whether an additional factor doesn’t trace to the particular constellation of doctrines that emerged within Hilary Putnam’s writings on “scientific realism” in the 1965-1975 period. Several supplementary themes there coalesce in an unfortunate manner.

(1) If a scientific practice has managed to obtain a non-trivial measure of practical capacity, there must be underlying externalist reasons that support these practices, in the same way that external considerations of environment and canvassing strategy help explicate why honey bees collect pollen in the patterns that they do. (This observation is sometimes called Putnam’s “no miracles argument”).

(2) Richard Boyd subsequently supplemented (1) (and Putnam accepted) with the restrictive dictum that “the terms in a mature scientific theory typically refer,” a developmental claim that strikes me as factually incorrect and supportive of the “natural kinds” doctrines that we should likewise eschew as descriptively inaccurate.

(3) Putnam further aligned his semantic themes with Saul Kripke’s contemporaneous doctrines with respect to modal logic which eventually led to the strong presumption that the “natural kinds” that science will eventually reveal will also carry with them enough “hyperintensional” ingredients to ensure that these future terminologies will find themselves able to reach coherently into whatever “possible worlds” become codified within any ultimate enclosing Theory T (whatever it may prove to be like otherwise). This predictive postulate allows present-day metaphysicians to confidently formulate their structural conclusions with little anxiety that their armchair-inspired proposals run substantive risk of becoming overturned in the scientific future.

Now I regard myself as a “scientific realist” in the vein of (1), but firmly believe that the complexities of real life scientific development should dissuade us from embracing Boyd’s simplistic prophecies with respect to the syntactic arrangements to be anticipated within any future science. Direct inspection shows that worthy forms of descriptive endeavor often derive their utilities from more sophisticated forms of data registration than thesis (2) presumes. I have recently investigated the environmental and strategic considerations that provide classical optics with its astonishing range of predictive and instrumental successes, but the true story of why the word “frequency” functions as such a useful term within these applications demands a far more complicated and nuanced “referential” story than any simple “‘frequency’ refers to X” slogan adequately captures (the same criticism applies to “structural realism” and allied doctrines).

Recent developments within so-called “multiscalar modeling” have likewise demonstrated how the bundle of seemingly “divergent relations” connected with the notion of classical “force” can be more effectively managed by embedding these localized techniques within a more capacious conceptual architecture than Theory T axiomatics anticipates. These modern tactics provide fresh exemplars of novel reconceptualizations in the spirit of the innovations that had originally impressed our philosopher/scientist forebears (Imitation of Rigor examines some of these new techniques in greater detail). I conclude that “maturity” in a science needn’t eventuate in simplistic word-to-world ties but often arrives at more complex varieties of semantic arrangement whose strategic underpinnings can usually be decoded after a considerable expenditure of straightforward scientific examination.

In any case, Putnam’s three supplementary theses, taken in conjunction with the expectations of standard “Theory T thinking” outfits armchair philosophy with a prophetic telescope that allows it to peer into an hypothesized future in which all of the irritating complexities of renormalization, asymptotics and cross-scalar homogenization will have happily vanished from view, having appeared along the way only as evanescent “Galilean idealizations” of little metaphysical import. These futuristic presumptions have convinced contemporary metaphysicians that detailed diagnoses of the sort that Hertz provided can be dismissed with an airy wave of the hand, “The complications to which you point properly belong to epistemology or the philosophy of language, whereas we are only interested in the account of worldly structure that science will eventually reach in the fullness of time.”

Through such tropisms of lofty dismissal, the accumulations of doctrine outlined in this note have facilitated a surprising reversion to armchair demands that closely resemble the constrictive requirements on viable conceptualization against which our historical forebears had originally rebelled. As a result, contemporary discussion within “metaphysics” once again finds itself flooded with a host of extraneous demands upon science with respect to “grounding,” “the best systems account of laws” and much else that doesn’t arise from the direct inspection of practice in Hertz’ admirable manner. As we noted, the scientific community of his time was greatly impressed by the realization that “fresh eyes” can be opened upon a familiar subject (such as Euclidean geometry) through the exploration of alternative sets of conceptual primitives and the manner in which unusual “extension element” supplements can forge unanticipated bridges between topics that had previously seemed disconnected. But I find little acknowledgement of these important tactical considerations within the current literature on “grounding.”

From my own perspective, I have been particularly troubled by the fact that the writers responsible for these revitalized metaphysical endeavors frequently appeal offhandedly to “the models of classical physics” without providing any cogent identification of the axiomatic body that allegedly carves out these “models.” I believe that they have unwisely presumed that “Newtonian physics” must surely exemplify some unspecified but exemplary “Theory T” that can generically illuminate, in spite of its de facto descriptive inadequacies, all of the central metaphysical morals that any future “fundamental physics” will surely instantiate. Through this unfounded confidence in their “classical intuitions,” they ignore Hertz’ warnings with respect to tricky words that “have accumulated around [themselves], more relations than can be completely reconciled amongst themselves.” But if we lose sight of Hertz’s diagnostic cautions, we are likely to return to the venerable realm of armchair expectations that might have likewise appealed to a Robert Boyle or St. Thomas Aquinas.

Discussion welcome.

The post The Rigor of Philosophy & the Complexity of the World (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

It may very well, owing to the condition of the world, and especially to the progress of knowledge, present itself at the same time to two or more persons who have had no intercommunication. Bentham and Paley formed nearly at the same date a utilitarian system of morals. Darwin and Wallace, while each ignorant of the other’s labours, thought out substantially the same theory as to the origin of species.--A.V. Dicey [2008] (1905) Lectures on the Relation between Law & Public Opinion in England during the Nineteenth Century, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, p. 18 n. 6 (based on the 1917 reprint of the second edition).

As regular readers know (recall), I was sent to Dicey because he clearly shaped Milton Friedman's thought at key junctures in the 1940s and 50s. So, I was a bit surprised to encounter the passage quoted above. For, I tend to associate interest in the question of simultaneous invention or multiple discovery with Friedman's friend, George J Stigler (an influential economist) and his son Steven Stigler (a noted historian of statistics). In fairness, the Stiglers are more interested in the law of eponymy. In his (1980) article on that topic, Steven Stigler cites Robert K. Merton's classic and comic (1957) "Priorities in Scientific Discovery: A Chapter in the Sociology of Science." (Merton project was revived in Liam Kofi Bright's well known "On fraud.")

When Merton presented (and first published it) he was a colleague of George Stigler at Columbia University (and also Ernest Nagel). In his (1980) exploration of the law of eponymy, Steven Stigler even attributes to Merton the claim that “all scientific discoveries are in principle multiple." (147) Stigler cites here p. 356 of Merton's 1973 book, The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations, which is supposed to be the chapter that reprints the 1957 article. I put it like that because I was unable to find the quoted phrase in the 1957 original (although the idea can certainly be discerned in it, but I don't have the book available to check that page).

Merton himself makes clear that reflection on multiple discovery is co-extensive with modern science because priority disputes are endemic in it. In fact, his paper is, of course, a reflection on why the institution of science generates such disputes. Merton illustrates his points with choice quotes from scientific luminaries on the mores and incentives of science that generate such controversies, many of which are studies in psychological and social acuity and would not be out of place in Rochefoucauld's Maximes. Merton himself places his own analysis in the ambit of the social theory of Talcott Parsons (another important influence on George Stigler) and Durkheim.

The passage quoted from Dicey's comment is a mere footnote, which occurs in a broader passage on the role of public opinion in shaping development of the law. And, in particular, that many developments are the effect of changes in prevaling public opinion, which are the effect of in the inventiveness of "some single thinker or school of thinkers." (p. 17) The quoted footnote is attached to the first sentence of remarkably long paragraph (which I reproduce at the bottom of this post).* The first sentence is this: "The course of events in England may often at least be thus described: A new and, let us assume, a true idea presents itself to some one man of originality or genius; the discoverer of the new conception, or some follower who has embraced it with enthusiasm, preaches it to his friends or disciples, they in their turn become impressed with its importance and its truth, and gradually a whole school accept the new creed." And the note is attached to 'genius.'

Now, often when one reads about multiple discovery (or simultaneous invention) it is often immediately contrasted to a 'traditional' heroic or genius model (see Wikipedia for an example, but I have found more in a literature survey often influenced by Wikipedia). But Dicey's footnote recognizes that in the progress of knowledge, and presumably division of labor with (a perhaps imperfect) flow of ideas, multiple discovery should become the norm (and the traditional lone genius model out of date).

In fact, Dicey's implicit model of the invention and dissemination of new views is explicitly indebted to Mill's and Taylor's account of originality in chapter 3 of On Liberty. (Dicey only mentions Mill.) Dicey quotes Mill's and Taylor's text: "The initiation of all wise or noble things, comes and must come from individuals; generally at first from some one individual." (Dicey adds that this is also true of folly or a new form of baseness.)

The implicit model is still very popular. MacAskill's account (recall) of Benjamin Lay's role in Quaker abolitionism (and itself a model for social movement building among contemporary effective altruists) is quite clearly modelled on Mill and Taylor's model. I don't mean to suggest Mill and Taylor invent the model; it can be discerned in Jesus and his Apostles and his been quite nicely theorized by Ibn Khaldun in his account of prophetic leadership. Dicey's language suggests he recognizes the religious origin of the model because he goes on (in the very next sentence of the long paragraph) as follows: "These apostles of a new faith are either persons endowed with special ability or, what is quite as likely, they are persons who, owing to their peculiar position, are freed from a bias, whether moral or intellectual, in favour of prevalent errors. At last the preachers of truth make an impression, either directly upon the general public or upon some person of eminence, say a leading statesman, who stands in a position to impress ordinary people and thus to win the support of the nation."

So far so good. But Dicey goes on to deny that acceptance of a new idea depends "on the strength of the reasoning" by which it is advocated or "even on the enthusiasm of its adherents." He ascribes uptake of new doctrines to skillful opportunism in particular by a class of political entrepreneurs or statesmanship (or Machiavellian Virtu) in the context of "accidental conditions." (This anticipates Schumpeter, of course, and echoes the elite theorists of the age like Mosca and Michels.) Dicey's main example is the way Bright and Cobden made free trade popular in England. There is space for new directions only after older ideas have been generally discredited and the political circumstances allow for a new orientation.

It's easy to see that Dicey's informal model (or should I say Mill and Taylor's model?) lends itself to a lot of Post hoc ergo propter hoc reasoning. So I am by no means endorsing it. But the wide circulation of some version of the model helps explain the kind of relentless repetition of much of public criticism (of woke-ism, neoliberalism, capitalism, etc.) that has no other goal than to discredit some way of doing things. If the model is right these are functional part of a strategy of preparing the public for a dramatic change of course. As I have noted Milton Friedman was very interested in this feature of Dicey's argument [Recall: (1951) “Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects” Farmand, 17 February 1951, pp. 89-93 [recall this post] and his (1962) "Is a Free Society Stable?" New Individualist Review [recall here]].

I admit we have drifted off from multiple discovery. But obviously, after the fact, multiple discovery in social theory or morals can play a functional role in the model as a signpost that the world is getting ready to hear a new gospel. By the end of the eighteenth century, utilitarianism was being re-discovered or invented along multiple dimensions (one may also mention Godwin, and some continental thinkers) as a reformist even radical enterprise. It was responding to visible problems of the age, although its uptake was not a foregone conclusion. (And the model does not imply such uptake.)

It is tempting to claim that this suggests a dis-analogy with multiple discovery in science. But all this suggestion shows is that our culture mistakenly expects or (as I have argued) tacitly posits an efficient market in ideas in science with near instantaneous uptake of the good ideas; in modern scientific metrics the expectation is that these are assimilated within two to five years on research frontier. But I resist the temptation to go into an extended diatribe why this efficient market in ideas assumption is so dangerous.

*Here's the passage:

The course of events in England may often at least be thus described: A new and, let us assume, a true idea presents itself to some one man of originality or genius; the discoverer of the new conception, or some follower who has embraced it with enthusiasm, preaches it to his friends or disciples, they in their turn become impressed with its importance and its truth, and gradually a whole school accept the new creed. These apostles of a new faith are either persons endowed with special ability or, what is quite as likely, they are persons who, owing to their peculiar position, are freed from a bias, whether moral or intellectual, in favour of prevalent errors. At last the preachers of truth make an impression, either directly upon the general public or upon some person of eminence, say a leading statesman, who stands in a position to impress ordinary people and thus to win the support of the nation. Success, however, in converting mankind to a new faith, whether religious, or economical, or political, depends but slightly on the strength of the reasoning by which the faith can be defended, or even on the enthusiasm of its adherents. A change of belief arises, in the main, from the occurrence of circumstances which incline the majority of the world to hear with favour theories which, at one time, men of common sense derided as absurdities, or distrusted as paradoxes. The doctrine of free trade, for instance, has in England, for about half a century, held the field as an unassailable dogma of economic policy, but an historian would stand convicted of ignorance or folly who should imagine that the fallacies of protection were discovered by the intuitive good sense of the people, even if the existence of such a quality as the good sense of the people be more than a political fiction. The principle of free trade may, as far as Englishmen are concerned, be treated as the doctrine of Adam Smith. The reasons in its favour never have been, nor will, from the nature of things, be mastered by the majority of any people. The apology for freedom of commerce will always present, from one point of view, an air of paradox. Every man feels or thinks that protection would benefit his own business, and it is difficult to realise that what may be a benefit for any man taken alone, may be of no benefit to a body of men looked at collectively. The obvious objections to free trade may, as free traders conceive, be met; but then the reasoning by which these objections are met is often elaborate and subtle, and does not carry conviction to the crowd. It is idle to suppose that belief in freedom of trade—or indeed any other creed—ever won its way among the majority of converts by the mere force of reasoning. The course of events was very different. The theory of free trade won by degrees the approval of statesmen of special insight, and adherents to the new economic religion were one by one gained among persons of intelligence. Cobden and Bright finally became potent advocates of truths of which they were in no sense the discoverers. This assertion in no way detracts from the credit due to these eminent men. They performed to admiration the proper function of popular leaders; by prodigies of energy, and by seizing a favourable opportunity, of which they made the very most use that was possible, they gained the acceptance by the English people of truths which have rarely, in any country but England, acquired popularity. Much was due to the opportuneness of the time. Protection wears its most offensive guise when it can be identified with a tax on bread, and therefore can, without patent injustice, be described as the parent of famine and starvation. The unpopularity, moreover, inherent in a tax on corn is all but fatal to a protective tariff when the class which protection enriches is comparatively small, whilst the class which would suffer keenly from dearness of bread and would obtain benefit from free trade is large, and having already acquired much, is certain soon to acquire more political power. Add to all this that the Irish famine made the suspension of the corn laws a patent necessity. It is easy, then, to see how great in England was the part played by external circumstances—one might almost say by accidental conditions—in determining the overthrow of protection. A student should further remark that after free trade became an established principle of English policy, the majority of the English people accepted it mainly on authority. Men, who were neither land-owners nor farmers, perceived with ease the obtrusive evils of a tax on corn, but they and their leaders were far less influenced by arguments against protection generally than by the immediate and almost visible advantage of cheapening the bread of artisans and labourers. What, however, weighed with most Englishmen, above every other consideration, was the harmony of the doctrine that commerce ought to be free, with that disbelief in the benefits of State intervention which in 1846 had been gaining ground for more than a generation.

Despite the reassuring pleasure that historians of medicine may feel when they recognise in the great ledgers of confinement what they consider to be the timeless, familiar face of psychotic hallucinations, cognitive deficiencies, organic consequences or paranoid states, it is impossible to draw up a coherent nosological map from the descriptions that were used to confine the insane. The formulations that justify confinement are not presentiments of our diseases, but represent instead an experience of madness that occasionally intersects with our pathological analyses, but which could never coincide with them in any coherent manner. The following are some examples taken at random from entries on confinement registers for those of ‘unsound mind’: ‘obstinate plaintiff’, ‘has obsessive recourse to legal procedures’, ‘wicked cheat’, ‘man who spends days and nights deafening others with his songs and shocking their ears with horrible blasphemy’, ‘bill poster’, ‘great liar’, ‘gruff, sad, unquiet spirit’. There is little sense in wondering if such people were sick or not, and to what degree, and it is for psychiatrists to identify the paranoid in the ‘gruff’, or to diagnose a ‘deranged mind inventing its own devotion’ as a clear case of obsessional neurosis. What these formulae indicate are not so much sicknesses as forms of madness perceived as character faults taken to an extreme degree, as though in confinement the sensibility to madness was not autonomous, but linked to a moral order where it appeared merely as a disturbance. Reading through the descriptions next to the names on the register, one is transported back to the world of Brant and Erasmus, a world where madness leads the round of moral failings, the senseless dance of immoral lives.

And yet the experience is quite different. In 1704, an abbot named Bargedé was confined in Saint-Lazare. He was seventy years old, and he was locked up so that he might be ‘treated like the other insane’. His principal occupation was

lending money at high interest, beyond the most outrageous, odious usury, for the benefit of the priesthood and the Church. He will neither repent from his excesses nor acknowledge that usury is a sin. He takes pride in his greed. Michel Foucault (1961) [2006] History of Madness, Translated by Jonathan Murphy and Jean Khalfa, pp. 132-133

In larger context, Foucault is describing how during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (the so-called 'classical age') a great number of people (Foucault suggests a number of 1% of the urban population) were locked up in a system of confinement orthogonal to the juridical system (even though such confinement was often practically indistinguishable from prison--both aimed at moral reform through work and sermons). This 'great confinement' included people with venereal disease, those who engaged in sodomy and libertine practices as well as (inter alia) those who brought dishonor (and financial loss) to their families alongside the mad and frenzied.

To the modern reader the population caught up in the 'great confinement' seems rather heterogeneous in character, but their commonality becomes visible, according to Foucault, when one realizes that it's (moral) disorder that they have in common from the perspective of classical learning. According to Foucault there is "no rigorous distinction between moral failings and madness." (p. 138) Foucault inscribes this (moral disorder of the soul/will) category into a history of 'Western unreason' that helps constitute (by way of negation) the history of early modern rationalism (with special mention of Descartes and Spinoza). Like a true Kantian, Foucault sees (theoretical) reason as shaped by practical decision as constitutive of the whole classical era (see especially p. 139). My present interest is not to relitigate the great Derrida-Foucault debate over this latter move, or Foucault's tendency to treat -- despite his nominalist sensibilities -- whole cultural eras as de facto organically closed systems (of the kind familiar from nineteenth century historiography).

My interest here is in the first two sentences of the quoted passage. It describes what Thomas Kuhn called 'incommensurability' in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn's Structure appeared in 1962, and initially there seems to have been no mutual influence. I don't want to make Foucault more precise than he is, but we can fruitfully suggest that for Foucault incommensurability involves the general inability to create a coherent mapping between two theoretical systems based on their purported descriptive content. I phrase it like to capture Foucault's emphasis on 'descriptions' and to allow -- mindful of Earman and Fine ca 1977 -- that some isolated terms may well be so mapped. As an aside, I am not enough of a historian of medicine (or philosopher of psychology) to know whether nosological maps can be used for such an exercise. (It seems like a neat idea!)

So, Foucault is thinking about ruptures between different successive scientific cultures pretty much from the start of his academic writing (recall this post on the later The Order of Things). In fact, reading History of Madness after reading a lot of Foucault's other writings suggests a great deal of continuity in Foucault's thought--pretty much all the major themes of his later work are foreshadowed in it (and it also helps explain that he often didn't have to start researching from scratch in later writings and lectures).

In fact, reading Foucault with Kuhn lurking in the background helps one see how important a kind of Kantianism is to Foucault's diagnosis of incommensurability. I quote another passage in the vicinity that I found illuminating:

The psychopathology of the nineteenth century (and perhaps our own too, even now) believes that it orients itself and takes its bearings in relation to a homo natura, or a normal man pre-existing all experience of mental illness. Such a man is in fact an invention, and if he is to be situated, it is not in a natural space, but in a system that identifies the socius to the subject of the law. Consequently a madman is not recognised as such because an illness has pushed him to the margins of normality, but because our culture situates him at the meeting point between the social decree of confinement and the juridical knowledge that evaluates the responsibility of individuals before the law. The ‘positive’ science of mental illness and the humanitarian sentiments that brought the mad back into the realm of the human were only possible once that synthesis had been solidly established. They could be said to form the concrete a priori of any psychopathology with scientific pretensions.--pp. 129-130

For Foucault, a concrete a priori is itself the effect of often indirect cultural construction or stabilization. In fact, for Foucault it tends to be an effect of quite large-scale and enduring ('solidly') social institutions (e.g., the law, penal/medical institutions) and material practices/norms. The discontinuity between concrete a priori's track what we may call scientific revolutions in virtue of the fact that systems of knowledge before and after a shift in a concrete a priori cannot possibly be tracking the same system of 'objects' (or 'empirical basis').

I don't mean to suggest that for Foucault a system of knowledge cannot be itself a source/cause of what he calls a 'synthesis' that makes a concrete a priori possible. That possibility is explicitly explored in (his discussion of Adam Smith in) his The Order of Things. But on the whole a system of knowledge tends to lag the major cultural shifts that produce a concrete a priori.

Let me wrap up. A full generation after Structure appeared there was a belated and at the time revisionary realization that Structure could be read as a kind of neo-Kantian text and, as such, was actually not very far removed from Carnap's focus on frameworks and other projects in the vicinity that were committed to various kinds of relativized or constitutive a prioris. This literature started, I think, with Reisch 1991. (My own scholarship has explored [see here; here] the surprising resonances between Kuhn's Structure and the self-conception of economists and the sociology of Talcott Parsons at the start of twentieth century and the peculiar fact that Kuhn's Structure was foreshadowed in Adam Smith's philosophy of science.) I mention Carnap explicitly because not unlike Carnap [see Stone; Sachs, and the literature it inspired], Foucault does not hide his debts to Nietzsche.

So here's my hypothesis and diagnosis: it would have been much more natural to read Structure as a neo/soft/extended-Kantian text if analytic philosophers had not cut themselves off from developments in Paris. While I do not want to ignore major differences of emphasis on scope between Kuhn and Foucault, their work of 1960 and 1962 has a great deal of family resemblance despite non-trivial differences in intellectual milieus. I actually think this commonality is not an effect of a kind of zeitgeist or the existence of an episteme--as I suggested in this post, it seems to be a natural effect of starting from a broadly domesticated Kantianism. But having said that, that it was so difficult initially to discern the neo-Kantian themes in Kuhn also suggests that not reading the French developments -- by treating 'continental thought' as instances of unreason (which is Foucault's great theme) -- also created a kind of Kuhn loss in the present within analytic philosophy.

Concluding our discussion of On Certainty, with guest Chris Heath.

We try one last time to get a handle on Wittgenstein's philosophy of science. How do people actually change their minds about fundamental beliefs?

The post Ep. 310: Wittgenstein On World-Pictures (Part Two) first appeared on The Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast.

We continue with Ludwig Wittgenstein's On Certainty (written 1951), with guest Christopher Heath.

What is Wittgenstein's philosophy of science as it's reflected in this book? We talk about Weltbilds (world pictures) and how these relate to language games, relativism, verification, paradigms, testimony, and more.

The post Ep. 310: Wittgenstein On World-Pictures (Part One) first appeared on The Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast.The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science has named Zina B. Ward (Florida State) the winner of its 2022 Popper Prize.

The Popper Prize, named for Karl Popper, is awarded to the best articles appearing in the journal which concern themselves with topics in the philosophy of science to which Popper made a significant contribution, as determined by the Editors-in-Chief and the British Society for the Philosophy of Science Committee.

Professor Ward won the prize for her “Registration Pluralism and the Cartographic Approach to Data Aggregation across Brains“. Here’s what the judges had to say about it:

In ‘Registration Pluralism and the Cartographic Approach to Data Aggregation across Brains’, Zina B. Ward tackles a methodological issue of central importance in cognitive neuroscience: how to register data from multiple subjects in a common spatial framework despite significant variation in human brain structure, that is, how to map activity in different subjects’ neural structures onto a single template or into a common representational space. In a typical fMRI-based investigation, experimenters run a series of subjects through a scanner and, if the experiment is fruitful, draw conclusions, from the data collected, about the functional contributions of certain areas of the brain—that, for instance, the ACC regulates emotional responses to pain. Such work presupposes normalization of the images from various subjects, so as to allow experimenters to claim that, across subjects, the same area of the brain exhibited elevated activity during scanning. The requirements of normalization might seem to pose a mere technical problem; perhaps with hard work and ingenuity, neuroscientists can identify the single, correct method for pairing brain areas or regions across subjects. Ward argues against this kind of monism. For principled reasons to do with the extent and nature of variation in neural structure—for example, variation in the location of sulci relative to cytoarchitectonic boundaries—Ward argues that the choice of spatial framework and method of registration must vary, depending on the purpose of a given study. No single method will simultaneously effect all of the correct pairings of relevance to cognitive neuroscience. From a practical standpoint, such methodological pluralism may seem daunting, and it might also seem excessively theory-laden. In response to such concerns, Ward offers and defends a series of constructive proposals concerning how to implement registration pluralism.

For its impressive theoretical and practical contributions to an issue of central importance in cognitive neuroscience, the BJPS Co-Editors-in-Chief and the BSPS Committee judge ‘Registration Pluralism and the Cartographic Approach to Data Aggregation across Brains’ to be worthy of the 2022 BJPS Popper Prize.

The prize includes £500.

Three others received honorable mention. They are:

You can learn more about the Popper Prize and see a list of past winners here.

Once upon a time there were four aristotelian causes; then Hume came along and discredited final, formal, and material causes. By a ruthless process of elimination efficient causation simply became causation. And, while in the Treatise Hume modelled such causation on the template of then ruling mechanical (scientific) philosophy with its emphasis on contact between and regular succession of cause and effect, in the more mature first Enquiry (1748) he invented, as the stanford encyclopedia of philosophy claims with surprise ("surprisingly enough,"), the modern conception of causation by offering a counterfactual definition of it, "We may define a cause to be an object followed by another, and where all the objects, similar to the first, are followed by objects similar to the second. Or, in other words, where, if the first object had not been, the second never had existed.” Proving, once again, that lack of logical rigor need not prevent fertile insight.

The fairy tale is not wholly misleading. But note three caveats: first, final causes remained respectable throught the nineteenth century in various scientific contexts (not the least physics and biology). I leave aside to what degree teleology is still lurking in contemporary sciences.

Second, the reduction from four to one kind of cause hides the deployment of a whole range of 'funky' causes. Among the more prominent of these funky causes are (i) eminent causes, where qualities or properties of the effect are already contained in the cause.* Crucially, the cause and the effect are fundamentally unalike or differ in nature.* But also (ii) immanent causes that aim to capture the idea that some effects take place within the cause of them. In recent metaphysics such causes are understood as (free and) moral agents, but in Spinoza, immanent causation is a feature of the one and only substance (who is not well understood as a moral agent). The most controversial funky cause were causes that (iii) were simultaneous with their effects over enormous distances. Hume goes after this with an argument that, if succesful, would suggest that the existence of simultaneous cause-effect relations would undermine the very possibility of succession, and so no motion would be possible, "and all objects must be co-existent." (Treatise 1.2.3.7-8) And as the new science became organized it became very tempting to treat (iv) laws of nature as (second) causes.+ (This is especially prominent in those who denied occasionalism.)

A final example of what I have in mind here is (V) the significance of causes that can jump the invisible/visible or (insensible/sensible) barrier(s). The hidden causal sources are often called 'powers,' which are responsible for manifest effects. In fact, in the early modern period this is one of the main expanatory causal schemes. It's because this is scheme is so influential in the early modern period, that in the Treatise, Hume uses features of it to articulate the problem of induction, which, of course, even in Hume contains multiple problems of induction [recall here].

As an aside, which is also the implied moral of the fairy tale, that more than four causes were tried out during a fertile intellectual age like the early modern period is no surprise. For, if we want to distinguish and classify the great variety of differences that, in a sense, make a difference even Aristotle's four causes may seem too few. I suspect the historical path dependency of this fact -- a great variety of differences that make a difference were labeled a 'cause' -- has made it so elusive to offer a unified, semantic analysis of causation. Historically there have been many paradigmatic causes that really fit in different boxes. And so our contemporary, ingenious analysts can always generate a counter-example or find an intuitive challenge to any attempt to offer a hegemonic definition or analysis.**

The aside is really the third caveat. In so far as one notion of causation predominated (be it the regularity, counterfactual or manipulative view) in which the homogeneous causal-effect structure is fairly restrictive, but what can enter into the relata is rather permissive, this predominance re-opens the door to new kinds of causes that aim to track differences that make a difference not well served by such homogeneity, especially if these can be operationalized with new mathematical techniques and improved computing power falling in price. We can understand, say, probabilistic causation as one such example, and hybrids that we find in causal networks as another kind of example.

*Structurally that's very close to a formal cause, but the formal cause can be highly abstract entity or feature whereas the eminent cause need not be so. (Although confusingly an eminent cause can, in scholastic jargon, cause formally.) In addition, the content of a formal cause often is similar in nature to the effect (or features of it).

+Second because God would then be the first cause.

**Notice that my explanation here is compatible with Millgram's of the same challenge in The Great Endarkenment, but differs in emphasis.

Perhaps eventually an overall Big Picture will emerge—and perhaps not: Hegel thought that the Owl of Minerva would take wing only at dusk (i.e., that we will only achieve understanding in retrospect, after it’s all over), but maybe the Owl’s wings have been broken by hyperspecialization, and it will never take to the air at all. What we can reasonably anticipate in the short term is a patchwork of inference management techniques, along with intellectual devices constructed to support them. One final observation: in the Introduction, I gave a number of reasons for thinking that our response to the Great Endarkenment is something that we can start working on now, but that it would be a mistake at this point to try to produce a magic bullet meant to fix its problems. That turns out to be correct for yet a further reason. Because the approach has to be bottom-up and piecemeal, at present we have to suffice with characterizing the problem and with taking first steps; we couldn’t possibly be in a position to know what the right answers are.

Thus far our institutional manifesto. Analytic philosophy has bequeathed to us a set of highly refined skills. The analytic tradition is visibly at the end of its run. But those skills can now be redirected and put in the service of a new philosophical agenda. In order for this to take place, we will have to reshape our philosophical pedagogy—and, very importantly, the institutions that currently have such a distorting effect on the work of the philosophers who live inside them. However, as many observers have noticed, academia is on the verge of a period of great institutional fluidity, and flux of this kind is an opportunity to introduce new procedures and incentives. We had better take full advantage of it.--Elijah Millgram (2015) The Great Endarkenment: Philosophy for an Age of Hyperspecialization, p. 281

There is a kind of relentless contrarian that is very smart, has voracious reading habits, is funny, and ends up in race science and eugenics. You are familiar with the type. Luckily, analytic philosophy also generates different contrarians about its own methods and projects that try to develop more promising (new) paths than these. Contemporary classics in this latter genre are Michael Della Rocca's (2020) The Parmenidean Ascent, Nathan Ballantyne's (2019) Knowing Our Limits, and Elijah Millgram's (2015) The Great Endarkenment all published with Oxford. In the service of a new or start (sometimes presented as a recovery of older wisdom), each engages with analytic philosophy's self-conception(s), its predominate methods (Della Rocca goes after reflective equilibrium, Millgram after semantic analysis, Ballantyne after the supplements the method of counter example), and the garden paths and epicycles we've been following. Feel free to add your own suggestions to this genre.

Millgram and Ballantyne both treat the cognitive division of labor as a challenge to how analytic philosophy is done with Ballantyne opting for extension from what we have and Millgram opting for (partially) starting anew (about which more below). I don't think I have noticed any mutual citations. Ballantyne, Millgram, and Della Rocca really end up in distinct even opposing places. So, this genre will not be a school.

Millgram's book, which is the one that prompted this post, also belongs to the small category of works that one might call 'Darwinian Aristotelianism,' that is, a form of scientific naturalism that takes teleological causes of a sort rather seriously within a broadly Darwinian approach. Other books in this genre are Dennett's From Bacteria to Bach and Back (which analyzes it in terms of reasons without a reasoner), and David Haig's From Darwin to Derrida (which relies heavily on the type/token distinction in order to treat historical types as final causes). The latter written by an evolutionary theorist.* There is almost no mutual citation in these works (in fact, Millgram himself is rather fond of self-citation despite reading widely). C. Thi Nguyen's (2020) Games: Agency as Art may also be thought to fit this genre, but Millgram is part of his scaffolding, and Nguyen screens off his arguments from philosophical anthropology and so leave it aside here.

I had glanced at Millgram's book when I wrote my piece on synthetic philosophy, but after realizing that his approach to the advanced cognitive division of labor was orthogonal to my own set it aside then.++ But after noticing intriguing citations to it in works by C. Thi Nguyen and Neil Levy, I decided to read it anyway. The Great Endarkenment is a maddening book because the first few chapters and the afterward are highly programmatic and accessible, while the bulk of the essays involve ambitious, revisionary papers in meta-ethics, metaphysics, and (fundementally) moral psychology (or practical agency if that is a term). The book also has rather deep discussions of David Lewis, Mill, and Bernard Williams. The parts fit together, but only if you look at them in a certain way, and only if you paid attention in all the graduate seminars you attended.

Millgram's main claim in philosophical anthropology is that rather than being a rational animal, mankind is a serial hyperspecializing animal or at least in principle capable of hyperspecializing serially (switching among different specialized niches it partially constructs itself). The very advanced cognitive division of labor we find ourselves in is, thus, not intrinsically at odds with our nature but actually an expression of it (even if Millgram can allow that it is an effect of economic or technological developments, etc.). If you are in a rush you can skip the next two asides (well at least the first).

As an aside, first, lurking in Millgram's program there is, thus, a fundamental critique of the Evolutionary Psychology program that takes our nature as adapted to and relatively fixed by niches back in the distant ancestral past. I don't mean to suggest Evolutionary Psychology is incompatible with Millgram's project, but it's fundamental style of argument in its more prominent popularizations is.

Second, and this aside is rather important to my own projects, Millgram's philosophical anthropology is part of the account of human nature that liberals have been searching for. And, in fact, as the quoted passages reveal, Millgram's sensibility is liberal in more ways, including his cautious preference for "bottom-up and piecemeal" efforts to tackle the challenge of the Great Endarkenment.+

Be that as it may, the cognitive division of labor and hyperspecialization is also a source of trouble. Specialists in different fields are increasingly unable to understand and thus evaluate the quality of each other's work including within disciplines. As Millgram notes this problem has become endemic within the institution most qualified to do so -- the university -- and as hyper-specialized technologies and expertise spread through the economy and society. This is also why society's certified generalists -- journalists, civil servants, and legal professionals -- so often look completely out of their depth when they have to tackle your expertise under time pressure.** It's his diagnosis of this state of affairs that has attracted, I think, most scholarly notice (but that may be a selection effect on my part by my engagement with Levy's Bad Beliefs and Nguyen's Games). Crucially, hyperspecialiation also involves the development of languages and epistemic practices that are often mutually unintelligible and perhaps even metaphysically incompatible seeming.

As an aside that is really an important extension of Millgram's argument: because the book was written just before the great breakthroughs in machine learning were becoming known and felt, the most obvious version of the challenge (even danger) he is pointing to is not really discussed in the book: increasingly we lack access to the inner workings of the machines we rely on (at least in real time), and so there is a non-trivial sense in which if he is right the challenge posed by Great Endarkenment is accelerating. (See here for an framework developed with Federica Russo and Jean Wagemans to analyze and handle that problem.)

That is, if Millgram is right MacAskill and his friends who worry about the dangers of AGI taking things over for rule and perhaps our destruction by the machine(s) have it backwards. The odds are more likely that our society will implode and disperse -- like the tower of Babel that frames Millgram's analysis -- by itself. And that if it survives mutual coordination by AGIs will be just as hampered by the Great Endarkenment, perhaps even more so due to their path dependencies, as ours is.

I wanted to explore the significance of this to professional philosophy (and also hint more at the riches of the book), but the post is long enough and I could stop here. So, I will return to that in the future. Let me close with an observation. As Millgram notes, in the sciences mutual unintelligibility is common. And the way it is often handled is really two-fold: first, as Peter Galison has argued, and Millgram notes, the disciplines develop local pidgins in what Galison calls their 'trading zones.' This births the possibility of mutually partially overlapping areas of expertise in (as Michael Polanyi noted) the republic of science. Millgram is alert to this for he treats a lot of the areas that have been subject of recent efforts at semantic analysis by philosophers (knowledge, counterfactuals, normativity) as (to simplify) really tracking and trailing the alethic certification of past pidgins. Part of Millgram's own project is to diagnose the function of such certification, but also help design new cognitive machinery to facilitate mutual intelligibility. That's exciting! This I hope to explore in the future.

Second, as I have emphasized in my work on synthetic philosophy, there are reasonably general theories and topic neutralish (mathematical and experimental) techniques that transcend disciplines (Bayesianism, game theory, darwinism, actor-network, etc.). On the latter (the techniques) these often necessetate local pidgins or, when possible, textbook treatments. On the former, while these general theories are always applied differently locally, they are also conduits for mutual intelligibility. (Millgram ignores this in part.) As Millgram notes, philosophers can make themselves useful here by getting MAs in other disciplines and so facilitate mutual communication as they already do. That is to say, and this is a criticism, while there is a simultaneous advancement in the cognitive division of labor that deepens mutual barriers to intelligibility, some of this advance generates possibilities of arbitrage (I owe the insight to Liam Kofi Bright) that also accrue to specialists that help transcend local mutual intelligibility.** So, what he takes to be a call to arms is already under way. So, let's grant we're on a precipice, but the path out is already marked.

*Because of this Millgram is able to use the insights of the tradition of neo-thomism within analytic philosophy to his own ends without seeming to be an Anscombe groupie or hinting darkly that we must return to the path of philosophical righteousness.

+This liberal resonance is not wholly accidental; there are informed references to and discussions of Hayek.

** Spare a thought for humble bloggers, by the way.

++UPDATE: As Justin Weinberg reminded me, Millgram did a series of five guest posts at DailyNous on themes from his book (here are the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth entries.) I surely read these, and encourage you to read them if you want the pidgin version of his book.

What, in short, we wish to do is to dispense with 'things'. To 'depresentify' them. To conjure up their rich, heavy, immediate plenitude, which we usually regard as the primitive law of a discourse that has become divorced from it through error, oblivion, illusion, ignorance, or the inertia of beliefs and traditions, or even the perhaps unconscious desire not to see and not to speak. To substitute for the enigmatic treasure of 'things' anterior to discourse, the regular formation of objects that emerge only in discourse. To define these objects without reference to the ground, the foundation of things, but by relating them to the body of rules that enable them to form as objects of a discourse and thus constitute the conditions of their historical appearance. To write a history of discursive objects that does not plunge them into the common depth of a primal soil, but deploys the nexus of regularities that govern their dispersion.--Michel Foucault (1969) "The Formation of Objects" chapter 3 in The Archaeology of Knowledge, translated by A.M. Sheridan Smith [1972], pp. 52-3 in the 2002 edition.

More than thirty years ago there was a buzz around Foucault and 'social constructivism' on campus. I don’t think I was especially aware of what this was about, but along the way I took a course in the ‘experimental college’ (a relic from the campus turmoil of an earlier generation) where I was introduced to the idea by way of the classic, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, then twenty five years old. (It was published in 1966.)

I never got around to reading Foucault as an undergraduate, but I was in graduate school studying with Martha Nussbaum when her (1999) polemic against Butler appeared. (I assume the essay was triggered by the second edition of Gender Trouble, but I am not confident about it.) This essay has a passage that nicely sumps up the general attitude toward Foucault that I was exposed to:

I was not nudged into reading Butler’s Gender Trouble during my graduate research (eventually when I became an instructor my own broad eduction started). However, I was confronted with the recent prominence of French postmodernist thought in works that now would be classified as foundational to STS, but that I was reading in virtue of my interest in the history of science such as Pickering’s The Mangle of Practice, which could generate heated debate among the PhD students. What made those debates frustrating was that we lacked distinctions so we often would talk passed each other.

A good part of those debates died down and were, subsequently domesticated after the publication of Hacking’s (1999) The Social Construction of What?, which we read immediately after it appeared. Hacking didn’t settle any debates for us, but allowed us to do more sober philosophy with it and while I do not want to credit him solely without mention of Haslanger, his book certainly contributed to the normalization and disciplining of the debate. Hacking and Haslanger also visited shortly thereafter, and so could ask for clarifications. Interestingly enough, in that book Hacking treats Foucault as a constructivist in ethical theory akin to Rawls, although he notes that others (Haslanger) treat Foucault as an ancestor to the idea that reality is constructed 'all the way down.'

As regular readers know my own current interest in Foucault is orthogonal to questions of construction. But I was struck by the fact that in his Foucault: His Thought, His Character, Paul Veyne treats Foucault fundamentally (not wholly without reason) as a Humean nominalist (and a certain kind of Nietzschean skeptic). And, in fact, the nominalism is itself exhibited by a certain kind of positivism about facts. (Deleuze might add quickly: a positivism about statements.) Veyne is not a reliable guide to matters philosophical, but I wondered if Foucault’s purported social constructivism was all based on a game of telephone gone awry in translation and academic celebrity culture.*

Now, if we look at the passage quoted at the top of the post, we can certainly why Foucault was treated as a social constructivist. The first few sentences in the quoted paragraph do look like a form of linguistic idealism. And this sense remains even if one has a dim awareness that the passage seems primarily directed against a kind phenomenology [“presentify” is clearly an allusion to Husserls [Vergegenwartigung]], even (perhaps) trolling Heidegger (“primal soil”).

However, the point of the passage is not ontology. It’s method. (No surprise because that is sort of the general aim of the Archeology of Knowledge.) And this, is in fact instructive of Foucault’s larger project. In the passage, Foucault is, in fact, explaining that he will try to leave aside questions of ontology in his own project. This is not to deny he is interested in what we might call epistemology. But the epistemology he is exploring is what one might call discursive authority. And the effect of such authority is “the regular formation of objects that emerge only in discourse.” (emphasis added).

In fact, Foucault here is not far removed from Quine (but in a way to be made precise). In one of the most Whitehead-ian passages of Two Dogmas, Quine writes: “The physical conceptual scheme simplifies our account of experience because of the way myriad scattered sense events come to be associated with single so-called objects; still there is no likelihood that each sentence about physical objects can actually be translated, however deviously and complexly, into the phenomenalistic language. Physical objects are postulated entities which round out, and simplify our account of the flux of experience.”

Now, don’t be distracted by Quine’s ‘sense events’ or empiricism. For, what Foucault is interested in is the manner by which (to quote Quine again) ‘myriad scattered sense events come to be associated with single so-called objects.’ In particular, (and now I am back to Foucault) “the body of rules that enable them to form as objects of a discourse.” This body of rules is characteristic of an authoritative discipline. And in particular, Foucault is interested in what the social effects are of simplifications produced by postulated entities in the human sciences on these sciences and larger society. I don’t mean to suggest this is Foucault’s only game. He is also interested in the social structures that stabilize the possibility of semantics across disciplines in a particular age.

To be sure, in Quine the epistemology of discursive authority is only treated cursory (in the context of regimentation). Whereas Foucault is focused on how the sciences acquire and constitute (even replicate) such authority. But that is compatible with all kinds of ontologies in Quine’s sense or, to be heretical for a second, a metaphysically robust realism; notice Foucault’s own hint of a ‘rich, heavy, immediate plenitude.' One will not get more than hints from Foucault on what his answers might be to the kind of epistemological or metaphysical questions we are trained to ask. That, of course, is a feature not a bug of his project.

*As an aside, we can see the shifting perspectives on Foucault's role in social constructivism in Philosophy Compass review articles. Back in 2007 Ron Mallon treats Foucault as a kind of fellow-traveller of social constructivism:

By contrast, Ásta, writing in 2015, treats Foucault (quite rightly) as a source for Hacking's account of the The looping effect which "is the phenomenon where X is being described or conceptualized as F makes it F." And then notes that "scholars disagree over whether Foucault himself allows for a role for epistemic reasons or whether the development of institutions and cultural practices is determined by power relations alone3 should not commit us to the view that the only force of human culture is power. " Here in a note Ásta cites not Foucault, but Habermas' famous criticism in ‘ Taking Aim at the Heart of the Present’. Cf. Nussbaum's hedged on this very point in the passage quoted above.

A few days ago a prominent economist hereafter (PE) I follow on twitter and enjoy bantering with mentioned, en passant, that PE had used ChatGPT to submit a referee report. (I couldn't find the tweet, so that's why I am not revealing his identity here.) Perhaps PE did so in the context of me entertaining the idea to use it in writing an exam because I have been experimenting with that. I can't say yet it is really a labor saving device, but it makes the process less lonely and more stimulating. The reason it is not a labor saving device is because GPT is a bullshit artist and you constantly have to be on guard it's not just making crap up (which it will then freely admit).

I don't see how I can make it worth my time to get GPT to write referee reports for me given the specific textual commentary I often have to make. I wondered -- since I didn't have the guts to ask PE to share the GPT enabled referee report with me -- if it would be easier to write such a joint report in the context of pointing out mistakes in the kind of toy models a lot of economics engages in. This got me thinking.

About a decade ago I was exposed to work by Allan Franklin and Kent Staley (see here) and (here). It may have been a session at a conference before this work was published; I don't recall the exact order. But it was about the role of incredibly high statistical significance standards in some parts of high energy physics, and the evolution of these standards over time. What was neat about their research is that it also was sensitive to background pragmatic and sociological issues. And as I was reflecting on their narratives and evidence, it occurred to me one could create a toy model to represent some of the main factors that should be able to predict if an experimental paper gets accepted, and where failure of the model would indicate shifting standards (or something interesting about that).

However, back home, I realized I couldn't do it. Every decision created anxiety, and i noticed that even simple functional relations were opportunities for agonising internal debates. I reflected on the fact that while I had been writing about other people's models and methods for a long time (sometimes involving non-trivial math), I had never actually tried to put together a model because all my knowledge about science was theoretical and self-learned. I had never taken graduate level science courses, and so never had been drilled in the making of even basic toy-models. This needn't been the end of the matter because all I needed to do was be patient and work through it in trial and error or, more efficiently, find a collaborator within (smiles sheepishly) the division of labor. But the one person I mentioned this project to over dinner didn't think it was an interesting modeling exercise because (i) my model would be super basic and (ii) it was not in his current research interests to really explore it. (He is super sweet dude, so he said it without kicking down.)

Anyway, this morning, GPT and I 'worked together' to produce Model 7.0.

Model 7.0 is a toy model that represents the likelihood a scientific paper is accepted or rejected in a field characterized as 'normal science' based on several factors. I wanted to capture intuitons about the kind of work it is, but also sociological and economic considations that operate in the background. I decided the model needed to distinguish among four kinds of 'results':

The model is shaped by the lack of interest in replications. Results that refute central tenets of a well confirmed theory need to pass relatively high evidential treshholds (higher than in Rii and Riii). I decided that experimental cost (which I would treat as a proxy for difficulty) would enter into decisions about relative priority of Rii and Riii. In addition, there were differences of standards in fields defined by robust background theories (or not so robust). As robustness goes up baseline standards of significance that need to be met, too.

I thought it clever to capture a Lakatosian intuition that results in a core and result on a fringe are treated differently. And I also wanted to capture the pragmatic fact that journal space is not unlimited and that its supply is shaped by the number of people chasing tenure.

So, in model 7.0 we can distinguish among the following variables

I decided that the relationship between journal space and number of people seeking tenure would be structurally the same in all four kinds of results. As the number of people seeking tenure in a field (N) increases, journal space availability (α) also increases, leading to a decrease in the importance of the other three variables (Θ, Σ, Ρ) in determining the probability of acceptance (P(Accepted) and so this became 'α / (α + k * N)' in all the functions. k represents the rate of decrease in significance threshold with increase in number of replications, which GTP thought clever to include. (Obviously, if you think that in a larger field it gets harder to publish results at a threshhold you would change signs here, etc.)

The formula for accepting papers for four different kind of results in a given field with a shared backgrond theory is given as follows:

For Rii and Riii, the formula also includes an additional term h(C, Rii) or h(C, Riii) respectively, which represents the effect of cost on the likelihood of acceptance. The function h is such that as costs go up, there is a greater likelihood that Riii will be accepted than Rii. We are more interested in a new particle than we are in a changing parameter that effects some measurements only. For Riv, the formula includes an additional term g(Σ, Ρ, Riv), which represents the impact of the robustness of the scientific theory being tested and the quality of the experimental design on the likelihood of acceptance. The standard for Riv is much higher than for Rii and Riii, as it requires an order of magnitude higher level of statistical significance.

It is not especially complicated to extend this kind of model to capture the idea that journals with different prestige game relative acceptance rates, or that replications (Ri) with non trivial higher statistical power do get accepted (for a while), but that's for future work.:)

I decided to pause at Model 7.0 because GPT seemed to be rather busy helping others. I was getting lots of "Maybe try me again in a little bit" responses. And I could see that merely adding terms was not going to be satisfying. I needed to do some thinking about the nature of this model and play around with it. Anyway, GPT also made some suggestions on how to collect data for such a model, how to operationalize different variables, and how to refine it, but I have to run to a lunch meeting. And then do a literature survey to see what kind of models are out there. It's probably too late for me to get into the modeling business, but I suspect GPT like models will become lots of people's buddies.

But perhaps one should reverse the problem and ask oneself what is served by the failure of the prison; what is the use of these different phenomena that are continually being criticized; the maintenance of delinquency, the encouragement of recidivism, the transformation of the occasional offender into a habitual delinquent, the organization of a closed milieu of delinquency. Perhaps one should look for what is hidden beneath the apparent cynicism of the penal institution, which, after purging the convicts by means of their sentence, continues to follow them by a whole series of 'brandings' (a surveillance that was once de jure and which is today de facto; the police record that has taken the place of the convic's passport) and which thus pursues as a 'delinquent' someone who has acquitted himself of his punishment as an offender. Can we not see here a consequence rather than a contradiction? If so, one would be forced to suppose that the prison, and no doubt punishment in general, is not intended to eliminate offences, but rather to distinguish them, to distribute them, to use th!m; that it is not so much that they render docile those who are liable to transgress the law, but that they tend to assimilate the transgression of the laws in a general tactics of subiection.--Michel Foucault (1975) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison [Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison] translated by Alan Sheridan, pp. 272.

The passage quoted above occurs in the section where Foucault steps back from his account of the 'birth' of a prison and reminds his reader that he is researching and writing his book during "prisoners' revolts of recent weeks." (p. 268) And some readers, then and now, will be familiar with Foucault's activism on behalf of those prisoners. Foucault goes on to note that such revolts elicit a predictable response from (what one might call) enlightened, bien pensant public opinion: "the prisoners' revolts...have been attributed to the fact that the reforms proposed in 1945 never really took effect; that one must therefore return to the fundamental principles of the prison." (p. 268) And Foucault goes on to note that the (seven) principles that entered into the 1945 reform and the predictable response to their failure are a return of the same with a history of "150 years," (p. 269): "Word for word, from one century to the other, the same fundamental propositions are repeated. They reappear in each new, hard-won, finally accepted formulation of a reform that has hitherto always been lacking." (p. 270).*

A certain kind of economist -- often associated with public choice theory and/or Stigler's account of rent-seeking [hereafter the fusion of Chicago and Virginia] --, when confronted by a persistent and enduring failure of a social institution, will ask Cui bono? And what will follow is a story about persistent rents, and rent-seeking. That is, while it is often presented in terms of methodological individualism of utility maximizing agents, the Chicago-Virginia fusion offers a functionalist account of the persistence of social institutions in virtue of the functions they serve to some socially powerful agents or classes of agents. (I put it like that to pay due hommage to the Smithian and Marxist (recall) roots of the emphasis on rent-seeking in the Chicago-Virginia fusion (recall this post on Stigler and recall here on Buchanan and Tullock.) If you don't like the word 'class' use 'representative agent' instead.