When Kurt Vonnegut reflected on the secret of happiness, he distilled it to “the knowledge that I’ve got enough.” And yet, both as a species and as individuals in an industrialist, materialistic, mechanistic culture, we are living under the tyranny of more — a civilizational cult we call progress. We have forgotten who we would be, and what our world would look like, if instead we lived under the benediction of enough.

How we got here, and what we might do about it, is what photographer, writer, illustrator, and wilderness guide Miriam Körner explores in Fox and Bear (public library) — a love letter to nature disguised as a modern fable of ecological grief and hope, partway between The Iron Giant and The Forest, yet entirely and consummately original, painstakingly illustrated in cut-out dioramas from reused and recycled cardboard, narrated with poetic tenderness and a passion for possibility.

Every day, Fox and Bear went into the forest to gather what there was to gather and to catch what there was to catch.

Day after day, the two friends forage and hunt together, watch the sun set and listen to the birds sing.

Life was good, thought Bear.

Picking berries and mushrooms,

hunting ants and mice,

catching rabbits and birds

kept them busy day after day.

But eventually, these joyful activities turn into tasks and the two friends get seduced by the trap of efficiency — that deadening impulse to optimize and operationalize doing at the expense of being.

As Bear and Fox begin gathering more and more seeds, catching more and more birds, laboring to water the seedlings and feed the birds, they suddenly find themselves with no time to watch the sunset or listen to birdsong.

This is how the allure of automation creeps in — Fox sets about inventing mechanical means of accomplishing the daily tasks, in the hope of liberating more time for leisure: an egg collector, a bird feeder, a water sprinkler, a berry picker.

Instead, the opposite happens as the forest begins to look like an industrial palace evocative of the Scottish philosopher John Macmurray’s cautionary observation that “we worship efficiency and success; and we do not know how to live finely.”

All this enterprise ends up consuming the time for leisure, subsuming the space for joy, affirming Hermann Hesse’s century-old admonition that “the high value put upon every minute of time, the idea of hurry-hurry as the most important objective of living, is unquestionably the most dangerous enemy of joy.”

Every day now, Fox and Bear cut down more trees to burn in the steam engines, so the egg collector could collect eggs and the water sprinkler would water the plants. At night, they filled the bird feeder and fixed the berry picker and built more cages until it was almost sunrise.

As Fox keeps dreaming up bigger and bigger engines, faster and faster machines, Bear finds himself “so tired he had no imagination left.”

Suddenly, he wakes up from the trance of busyness and remembers how lovely it was to simply wander the forest “and gather what there is to gather and catch what there is to catch.”

And, just like that, the two friends abandon the compulsions of progress and return to the elemental joy of simply being alive — creatures among creatures, on a world already perfectly tuned for every creaturely need. We have a finite store of sunsets in a life, after all.

Couple Fox and Bear with the Dalai Lama’s illustrated ethical and ecological philosophy for the next generation, then revisit the forgotten conservation pioneer William Vogt’s roadmap to civilizational survival and Denise Levertov’s stirring poem about our relationship to the natural world.

Illustrations courtesy of Miriam Körner

For a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first fifteen years). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.

The Marginalian has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

The last time math performance was this low for 13-year-olds was in 1990.

Over the last two decades, thousands of New York City children have struggled to pick up reading skills. Now, schools will be forced to change how they teach reading.

My son’s language is made of a bundle of sounds that do not exist in the Spanish that we speak around the Río de la Plata. He repeats syllables he himself invented, he alternates them with onomatopoeias, guttural sounds, and high-pitched shouts. It is an expressive, singing language. I wrote this on Twitter at 6:30 in the morning on a Thursday because Galileo woke me up at 5:30. He does this, madruga (there is no word for “madrugar”, “waking up early in the morning” in English, I want to know why). As I look after him, I open a Word document in my computer. I write a little while I hear “aiuuuh shíii shíiii prrrrrr boio boio seeehhh” and then some whispers, all this accompanied with his rhythmic stimming of patting himself on the chest or drumming on the walls and tables around the house.

My life with Gali goes by like this, between scenes like this one and the passionate kisses and hugs he gives me. This morning everything else is quiet. He brings me an apple for me to cut it for him in four segments. He likes the skin and gnaws the rest, leaving pieces of apples with his bitemarks all around the house. He also brings me a box of rice cookies he doesn’t know how to open. Then he eats them jumping on my bed. He leaves a trace of crumbles. Galileo inhabits the world by leaving evidence of his existence, of his habits, of his way of being in the world.

When we started walking the uncertain road to diagnosis, someone next of kin who is a children’s psychologist with a sort of specialisation in autism informally assessed him. She ruled (diagnosed, prognosed) that he wasn’t autistic, that we shouldn’t ask for the official disability certificate (because “labels” are wrong, she held), and that he should go on Lacanian therapy and music therapy on Zoom —now I think this is a ready-made sentence she just gives in general to anyone.

The most violent intervention in Galileo’s subjectivity is denying his being-disabled in an ableist world and his being-autistic in an allistic world. We, as a culture, have internalised the terror of disability so deep in our minds that we hurry to deny it. We are not willing to accept that what causes us so much angst and dread actually exists, that it is not an imagined ghost. Denying like this, in this delusional way, is an instinct only humans have. It is so human (so stupid) that it is not a survival instinct. When we deny autistic affirmation, we prepare the ground for its annihilation, i.e., for the annihilation of everyone who is autistic. Being autistic isn’t being an imperfect allistic, a not-yet-allistic person. Being disabled isn’t the same as being a flawed abled person. The denial of disability doesn’t amount to affirming an alternative ability, it implies the ableist annihilation of all vulnerability. But when disability is negated, able people do not survive either. We are born and we die in disability. How did it happen that we dare to imagine we can supersede need? (Maybe by the same process by which it is believed that capitalist profits are meant to satisfy human needs).

The instinct of denying disability is not innate, though. It is an intelligent trap designed to break communities apart, to disorganise, to debilitate us: not to make us disabled but to make us unable, powerless. This is how ableism works, de-politicising vulnerability and unease, making disability, at most, an object of pity and compassion, a matter of bad luck, a fate to try to twist and avoid.

***

Galileo’s spoken language has the musical texture of a genre he alone can perform. There was a (short) time when I thought that my role in his life was to be her translator, a mediation between him and the rest of the world. This is impossible for many reasons. The most important of them isn’t that I don’t get him (I don’t), it isn’t that I don’t speak his language (I don’t), or that no one (much less a mother) can or should mediate anyone. The main reason is that Galileo speaks as someone who plays in their instrument a piece that they have composed for themselves.

Sometimes language is comprehensible only insofar as one gets ready to listen to it as if they were in an empty church in front of a little bench where Rostropovich is about to play Bach’s suites with his Duport, and as if he were Bach himself. Then, and only then, we understand that we don’t understand, that we are at the gates of the incomprehensible. When is language more language than when it is spoken so incomprehensibly? The impossibility of interpreting oneself, myself, comes not only from the fact that no one controls or owns language. No one plays their own scores because no one creates their own language. No one, but Galileo and his equals. The autistic non-verbal language is that impossible thing that we try not to talk about when we talk, that we try to drown by talking too much, moving our hands, and writing for example this text. Autistic languages say what can’t be said in any articulated allistic “normal” language. Galileo speaks a language that complements other languages. This language of his is not the opposite of language: it perfects other languages, like music or silence do.

***

Does my son have a mother tongue? Do we speak to each other as mother and child? What do we tell each other when we chat? My son’s autism and his magic words lend me a whole new vocabulary for my own neurodiversity, a new and authentic view on my severe misophonia, hyperacusis, and hyperosmia, and on my life-long inability to grasp the majority of the rules of interpersonal relationships, among other things I thought were personal flaws that made me inferior. I won’t mask it anymore. I won’t keep it a secret anymore. Now I know how to talk about it, now I have names to name it. Maybe he will never speak his mother tongue or any other “normal” language, but he has taught me to speak a language in which I now can say what I couldn’t formulate in an allistic alien tongue. Stripping me of all the allistic and ableist expectations that have shaped the way I was meant to raise my children has liberated me from the suffering of trying to meet them myself. The truly difficult thing, besides raising an autistic child in an allistic world, besides being a non-verbal autistic child in an ableist world, is how to de-internalise all this life-long inferiorisation.

But I know he will tell me how.

Naomi Peralta, at left, prepares for a practice run at Highland High School in Albuquerque, N.M., in February.

In the past forty years, South Asian writers writing in English have made a significant showing at the Booker Prizes, the literary awards for the best book published in the UK and Ireland. Previous winners include Salman Rushdie (who has been nominated seven times, and whose novel Midnight’s Children won in 1981, introducing South Asian literature in English to the world with a bang), Arundhati Roy, Kiran Desai, Aravind Adiga—and even in 2022, Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka won for his novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida.

But the big news was sixty-five-year-old Indian writer Geetanjali Shree’s novel Tomb of Sand—translated by Daisy Rockwell—bringing home the Booker International Prize, the first time a book translated from Hindi had won in the prize’s nearly twenty-year history. Shree’s experimental and playful novel tells the story of Ma—an eighty-year-old bedridden woman who gets a new lease on life and goes on a journey back across a border that she thought she would never cross again. The English translation was originally published by Tilted Axis Press in the UK, and is now available from HarperCollins in the United States.

“Behind me and this book lies a rich and flourishing literary tradition in Hindi and in other South Asian languages,” Shree said in her acceptance speech. “World literature will be richer for knowing some of the finest writers in these languages, the vocabulary of life will increase from such an interaction.”

I spoke to Shree on Zoom one late night in California / mid-day in Delhi in between a flurry of events and appearances that have flooded her calendar since the prize was announced in October of 2022. The author of four other novels, Shree’s melodic voice and serene and vibrant demeanor made me wish I could teleport to her city and hear her speak in one of the many storied literary spaces there.

***

The Rumpus: Why do you write in Hindi?

Geetanjali Shree: The question itself says so much! That a person should be asked why she writes in her mother tongue, when it should be an absolutely natural thing. What else should I be writing in except in my mother tongue? It’s the first and most natural choice for a writer to be writing in her mother tongue. I think the question to be asked, normally, should be why you’re not writing in the mother tongue. But this says so much about our history, about our colonial past, about the place of English amongst the educated in [India], that it becomes almost unnatural that anyone who is educated to be writing not in English, but in another Indian language.

So yes, I write in Hindi because it’s my mother tongue. And I think, like a lot of us middle class Indians, I’ve also grown up with an English medium education. But when it comes to something like the arts and literature, it’s somehow so close to your bones that almost automatically you go into your mother tongue rather than in the language you have learned formally in school. I must add, because too easily it becomes a story about English versus other languages, that there is no such prejudice in my head or heart about it. Those who find for whatever reasons that English is the language they’ve expressed themselves in—they’re most welcome to do it.

Rumpus: Tomb of Sand (Ret Samadhi) was such a pleasure to read! The playfulness of the language really comes across, and the humor—also the deep themes of women and families and mothers and children and borders. You write: “Women are stories in themselves, full of stirrings and whisperings that float on the wind, that bend with each blade of grass.” Do these themes come up in all your books, and what was the inspiration for this one?

Shree: I haven’t sat down and studied what all themes I have written about before, since I don’t think of my books that way; but yes, all the themes you name and a few more as well. It is very pluralistic and very polyphonic and variegated. But yes, women easily and family, these are themes that I am interested in, but the trigger each time would be different.

In terms of inspiration, what has more and more become my way and more and more something that I have understood is that you don’t have to go for anything dramatic and big. The daily and the mundane are imbued with the big and the momentous. Every small and completely inane looking thing is also strangely connected to much bigger things, and each thing can have so many reverberations and echoes. What’s important is to find those layers, you know, as you go along. In almost all of my other works, I let small curiosities take me along.

The great poet and translator A.K. Ramanujan, in one of his diaries, he’d written that you don’t have to go looking for the poem, you just have to put yourself in a place where the poem will come to you. I really feel at one with that. You are carrying all your stories in you, from your surroundings, from your imagination, from your reality, from your observation, from your history, from your tradition—you’re carrying them all with you all the time. They’re building up. You just want to find the place where the story, for that moment, is going to emerge and begin to take shape and you can go with it. I just tried to put myself in a kind of mode of retreat and empty myself out and let the layers and whispers and the murmurs from within me become more audible and visible. And then I go along with that.

In this case, I think what set me off was just an image of an old person, an elderly person, lying with her back turned to the family, which is a very, very ordinary image, which is there in every family or everywhere, you know, elderly people who look like they have nothing more to do with this world. That image somehow formed inside me. Maybe it was there, maybe I picked it up from somewhere. And it stayed with me. And then that image stirred up my curiosity. What is it that this back is doing? Is it turning away from the world and from life, or is it turning away from the immediate family behind her? I followed that curiosity and that character, and that character started to do various things, which began to amaze me and amuse me and then a whole novel was on the way to being created.

Rumpus: Your book is dedicated to the Indian writer Krishna Sobti, another Hindi writer. Can you tell us about your relationship with her, and about the Hindi literary community in Delhi. It feels like a real community, as opposed to the United States where it is very institutionalized in terms of MFA programs.

Shree: The literary community in Delhi, well, it’s a very informal community at one level—and there’s everything that goes on within a community—there’s intrigue and politics and pettiness and support. In terms of Krishna Sobti, I consider her my guru and a great writer. She’s someone who people refer to as a “difficult writer,” which I find very unnecessary. I mean, why shouldn’t writing be difficult? The more important thing is whether it is good; difficult and good. Krishna Sobti was not an easy writer. You couldn’t just pick her up and read her in one second. But she was a writer of tremendous variety, and strength, and she was a person of great strength and forthrightness, and a person who you could absolutely iconify. She died a few years ago at the ripe old age of ninety-four, and right to the end she was very alert and aware about everything that was going on, very disturbed with the politics that were shaping up—and very upfront about whatever she had to say.

She was always very senior to me, and when we met, I was very much a new writer, but she was always very encouraging, not just to me but to others also, and she took all of us very seriously. She remembered what we were doing, and she would question us when we met. So right from the start, whenever I had the time, I would go and see her, which was actually not that often, but we just developed this relationship of great respect and affection. She was very, very kind and generous. We would sit down with a small brandy in the evening, which she would almost never finish, and she would ask about my work, and we would have that little evening together. It was lovely.

Rumpus: Your mentorship and community with Sobti makes me think of the many lines in your book about storytelling, and all the references you make to other writers. “Here’s the thing: A story can fly, stop, go, turn, be whatever it wants to be. That’s why our wise author Intizar Hussain once remarked that a story is like a nomad.” Is this an important part of your storytelling?

Shree: It is a line of thought which has probably been growing in me, perhaps something that I’ve been thinking more and more about. Perhaps it also comes from the fact that I am born into a literature which is in its modern form. Hindi literature very much belongs to the period just before [Indian] independence, and then concerns what went on after independence. And I think it was a period when social realism had a huge meaning and purpose for everyone who was writing because it was a new society, and everyone wanted to steer it towards a better future. So, this express purpose became the overriding concern for all the writers. Now that makes complete sense and I’m not deriding them at all, but I think it did become the sort of tacit rule and guideline that when you were writing, that you had to write about society for the betterment of society, and you had to do it in a way which is very easily communicable. You had to follow a certain sort of way which can be comprehended, the proper sort of story that a reader can immediately connect with.

I think somewhere I—when I say ‘I,’ I am not only talking about myself but a whole community of writers and artists—began to push back against social realism. Society comes into your work in so many different ways—it doesn’t have to be a verifiable, empirical, descriptive way. I think that spurred a lot of us on, and freed a lot of us. It’s like that Ramanujan quote again. I would say that we don’t have to go looking for the society, because almost whatever we do, society will come to it. So, just let yourself free in the field of literature and creativity. And, if you’re letting yourself free, then also realize that stories will not just go straight. Stories will go this way and that! There’ll be non sequiturs! There’ll be all kinds of breaks and incompleteness, and it’s okay to celebrate all that and see what happens.

Rumpus: Along with the meta-fictional elements in the book, there is also so much playfulness with the POV and characters and the way the story is being told. Do you feel like there is a lot of experimentation happening amongst modern Indian writers and artists today?

Shree: I don’t know if writers are thinking about that word “experimentation,” but it is happening in the course of searching out ways of saying what we are trying to say. Is there a lot of that kind of writing happening? Yes, the literature is very, very vibrant and many different things are happening. But I’ll also say that it’s not as if this is happening for the first time. I mean, if you go back to ancient literature, perhaps anywhere, and certainly in [India], you see it—look at our epics, take the Mahabharata. And what you’re calling experimentation I mean, come on, it’s full of every way of storytelling. It’s doing everything! It’s almost like there’s nothing new for you to do. In a way, I’m only copying. We carry on from things which have already been done, and we keep renewing them with our zeal and reinventing them and we keep trying to do something new. And sometimes, we manage with the same ingredients. And sometimes perhaps, we discover that we thought we were doing it for the first time, but it’s been done thousands of times before.

Rumpus: You speak so highly of your translators, not only mentioning your English translator Daisy Rockwell in your Booker acceptance speech, but also mentioning your French translator Annie Montaut. Tell me about what your relationship is like with your translators, and what the process of translating Tomb of Sand was like.

Shree: I’m so lucky to have these two translators for this book of mine. With both, actually, I’ve had a very, very rich relationship. I knew Annie, but I only met Daisy in person a few days before the Booker Awards Ceremony. It started with Daisy sending me a sample of the translation. When I saw those few pages, I felt that here’s somebody who really got the sense of things and is clearly enjoying the way I’m using language a bit crookedly—here’s somebody who seems to be in tune with it immediately.

After that, Daisy was sending me long questionnaires about lots of things that she needed clarified, which included messages where she said: “You know, it’s not really needed for the translation, but I need for myself, to have the context in my head when I’m translating.” So it was very fascinating, but quite excruciating sometimes for me because my work is not research based. I had to go back to my work and start sort of researching where I got certain metaphors from, what was the story behind my use of language, because when I am writing it’s just coming out. So, it became a conscious exercise of going back and researching and sometimes just guessing at what made me come to certain points in certain words and so on.

What’s important between the translator and the author is to share a rapport about the way of looking at things, you know, and feeling intensely about those things. So, I think the fact that Daisy felt as much love for language or playing with language made for a very strong foundation, and I think the outcome has been wonderful.

Rumpus: There has been a great deal of attention paid to the fact that Tomb of Sand was the first Indian language book to win the Booker International Prize. Why do you think Indian literature is not being recognized and translated as much as other languages and recognized on a world stage?

Shree: We must return again and again to the whole issue of hegemony of the English language. I think it’s unfortunate that English should become the pool where all literature is to be viewed. There should be more translations across languages; in fact, even across Indian languages. Why should Indians from different parts of the country have to read each other only in English? There’s a lot of things which are skewed in this whole translation story. In fact, in recent years, the quality of translations has really, really improved, so that’s a very hopeful sign. In fact, most of [the literature] that’s going out of South Asia is only literature written in English by South Asians.

Also, I don’t think there’s such a lot of translation being done of Indian languages. So, I think it’s a matter of accessibility—that it’s not been worked on and created. I think the world is really opening up, but it’s also made people quite insular. I hope something like the Booker win might do that. I was told that at the Frankfurt Book Fair, publishers were really interested in tapping translated works from Indian languages, rather than just going for the English. So, I think that’s a change one can immediately see, but it would only mean something if it becomes a sustained act.

Rumpus: How does it feel to be an artist in India, at this moment—or really in the world—with such a prevalence of right-wing and Nationalist leaders?

Shree: I’m really, really glad that you added in “the world.” I think that’s important because too often people talk about some places, like that’s where something is happening only. And there are other places where things are really, you know, hunky dory and you can do anything and get away with anything. That’s just not true. There are some trends in the world today, which are disturbing. There’s a tidal wave, you know. The world has opened up, but it’s also become more constricted. Vigilance has increased. Vigilance has become much easier than before, so everyone’s being watched. So, I’m glad you’re not making it India versus the world.

What’s happening in India… look, I mean, we respond to things at various levels. And let me tell you this: In some sense, the word has been endangered for a very long time, perhaps from the beginning. If the word is going to threaten the social order, it has to be stopped. Anything which is going to threaten the social and political order has to be stopped. And this has been going on perhaps forever. But I think writers cannot stop because writing for us is like breathing. We cannot stop. We have to carry on. By and large, I think that is what the situation is in India. So many people are writing and, indeed, I think there is a whole community which is carrying on saying what they want—even in this atmosphere of fear.

In a provocative essay, scholar and author Sophie Lewis, best known for her 2022 book in support of “family abolition,” makes the case for how society can not only protect trans children, but also learn from them. This is a call for a more expansive, generous, utopian way of thinking about the potential of youth:

The fear I inspired on the parent’s face riding the subway was what distressed me most about the incident in New York. Later that day, when I recounted the anecdote on Facebook, an acquaintance commented – unfunnily, I felt – that I was a “social menace”. A threat to our children, et cetera. Ha, ha. But what was the truth of the joke? What had I threatened exactly? A decade after the event, “The Traffic in Children,” an essay published in Parapraxis magazine in November 2022, provides an answer. According to its author, Max Fox, the “primal scene” of the current political panic about transness is:

a hypothetical question from a hypothetical child, brought about by the image of gender nonconformity: a child asks about a person’s gender, rather than reading it as a natural or obvious fact.

In other words, by asking “are you a girl or a boy?” (in my case non-hypothetically), the child reveals their ability to read, question and interpret — rather than simply register factually — the symbolisation of sexual difference in this world. This denaturalises the “automatic” gender matrix that transphobes ultimately need to believe children inhabit. It introduces the discomfiting reality that young people don’t just learn gender but help make it, along with the rest of us; that they possess gender identities of their own, and sexualities to boot. It invites people who struggle to digest these realities to cast about and blame deviant adults: talkative non-binary people on trains, for instance, or drag queens taking over “story hour” in municipal libraries.

This essay was the overall winner in the Undergraduate Category of the 2023 National Oxford Uehiro Prize in Practical Ethics

Written by University of Oxford student, Lukas Joosten

Most parents think they are helping their children when they give them a very high standard of life. This essay argues that giving luxuries to your children can, in fact, be morally impermissible. The core of my argument is that when parents give their children a luxurious standard of life, they foist an expectation for a higher standard of living upon their children, reducing their lifetime wellbeing if they cannot afford this standard in adulthood.

I argue for this conclusion in four steps. Firstly, I discuss how one can harm someone by changing their preferences. Secondly, I develop a model for the general permissibility of gift giving in the context of adaptive preferences. Thirdly, I apply this to the case of parental giving, arguing it is uniquely problematic. Lastly, I respond to a series of objections to the main argument.

I call the practice in question, luxury parenting. Luxury parenting consists of providing certain luxuries to your child which go beyond a reasonably good standard of living. I will consider this through a framework of gift giving, since luxury parenting can be understood as the continual gifting of certain luxuries to children. While my argument also applies to singular gifts of luxury to children, it is targeted at the continual provision of luxury goods and services to ensure a high standard of living throughout childhood.

Section 1: Preference Screwing

When we discuss harming one’s wellbeing, we are usually referring to taking some action which changes the actor’s situation so that they are further from their preferences. However, a person’s wellbeing can be harmed in the opposite way as well, by changing their preferences away from their situation. Consider the following example.

Wine pill: Bob secretly administers a pill to Will which changes his preferences so that he no longer enjoys cheap wine.

Will has been harmed here in some morally significant way without having received any immediate disbenefit. The harm consists in the effect on future preferences. We can call this type of harming “preference screwing”.

Preference Screwing: Making it more difficult for an actor to achieve a certain level of utility by changing the actor’s preferences so that there is a larger divergence between the preference set and the actor’s option set.

Section 2: Adaptive Preferences and Gift-giving

The theory of adaptive preferences tells us that people tend to return to their baseline happiness after positive or negative shocks to their wellbeing because people’s preferences adapt to their current situation. I argue this process of preference adaptation implies that some instances of gift-giving are impermissible, because consuming a high-quality gift, screws with the preferences of the recipient, so that they derive lower utility from future consumption of lower-quality variants of the good they were gifted.

There exists a vast literature debating the accuracy of adaptive preferences.[1] However, my argument only requires a weak restricted form of adaptive preferences. Namely it simply says that there is some negative impact of consuming expensive goods on the enjoyment of future cheap goods. That such an impact exists is generally empirically supported, even if the strength of the impact is debatable.[2]

It might be objected that if preferences are adaptive, then gift-giving has no long-term harm since, upon returning to the lower-quality good, preferences will adapt downward immediately. There are two independent reasons why this is not a problem for my argument.

Firstly, I don’t assume (and the empirics don’t support) complete adaption, only partial adaptation. This means that once the preferences of an actor have (partially) adapted up after consuming the higher-quality good, then if the actor returns to the lower-quality good, their preferences will adapt down but not completely, so there remains a long-lasting upwards pressure on their preferences.

Secondly, as discussed in section 3, since childhood is a formative life-phase, preferences adapt more quickly and more permanently for children. Luxury parenting thus fixes children’s preferences at a high point, which will take much longer to adapt back down in adulthood.

This allows us to develop a model of gift giving. When A gifts X to B, B’s lifetime wellbeing is affected in two ways. Firstly, there is the immediate positive (or negative if a particularly poor gift) utility derived by B’s consumption of X. Call this the immediate utility. Secondly there is the long-term impact of the gift’s preference screwing. The preference screwing effect is the total harm to the lifetime wellbeing of B incurred by B as a result of the preference screwing caused by consuming X. This allows us to state the following:

Net wellbeing impact of gift giving = immediate utility – preference screwing effect

Now, consider that preference screwing through gift-giving is usually not considered a form of wronging. Consider the following example:

Wine gift: Bob gifts a bottle of Château Latour to Will for his birthday. After thoroughly enjoying the wine, Will no longer enjoys cheap wines as much

In wine gift, we would not say that Bob has wronged Will. There are two distinctions between wine gift and wine pill which explain why gift giving to adults is generally permissible.

Firstly, wine gift is not necessarily a net negative for Will’s lifetime utility. The spike in utility of drinking the gifted bottle may outweigh the loss in utility from the future discounted happiness of drinking cheap wines. In wine pill, there is only a negative impact on Will’s utility (ignoring the health effects).

Secondly, and crucially, Will consents into receiving the gift. Generally, we think that a person’s potential complaint versus a particular action is much weaker when they consented into that action being conducted upon them.

This allows us to say that the permissibility of gift given is a function of the following two parameters:

The weight given to each is going to vary with one’s background intuitions on paternalism. Anti-paternalists might thus completely disregard the first parameter, arguing that given sufficient consent, gift-giving is always permissible. My argument is inclusive to a broad pluralism on this matter, since it avoids the 2nd parameter altogether, as discussed in section 3.

Section 3: Giving Children Luxuries

By evaluating luxury parenting on the two parameters, I argue that many instances of practice are impermissible.

Firstly, consider level of consent. Children are usually thought to lack the required capacities for autonomous decision making, such as critical thinking, time-relative agency (ownership of future interests) and independence[3]. This means that children, generally, cannot consent into receiving luxuries from their parents.

As such, we must adapt the model of consent for children. Brighouse suggests that the autonomy rights of children express themselves as fiduciary duties upon parents.[4] Parents thus have the authority to make decisions for their children, but this authority is limited by the duty to act in the child’s best interest. This means that both parents can permissibly give gifts to children, but only when those gifts appear to be in the best interest of the child. Assume now that, ceteris paribus, the non-welfare interests of children are unaffected in cases of gift giving. Given this assumption, we can say that the permissibility of child gift giving boils down to the expected net impact.

Luxury parenting is thus usually impermissible since it is particularly likely to lead to a negative expected net impact. This is because the preference screwing effect is likely to be strong, while the immediate benefit is small. Children are particularly vulnerable to preference screwing from luxury parenting for four reasons.

Firstly, childhood is an especially formative stage in life. Due to the ongoing development of the brain, the patterns children learn are going to be extra lasting. [5] This means that if preferences are formed to expect a high standard of living, these preferences are going to be especially sticky. If the child’s standard of living drops upon reaching adulthood, those preferences will likely adapt down less quickly and won’t adapt down completely.

Secondly, when children experience certain goods, they often experience them for the first time. If the first time they experience a particular good or service, they are experiencing an expensive variant of that good, they are likely to calibrate their future expectation on this expensive good, because they have no cheaper variants to compare it to.

Thirdly, children generally will have a lesser appreciation of the uniqueness or scarcity of the goods they experience at a high standard of living. In wine gift, Will is acutely aware that his drinking of Château Latour is a unique and temporary experience. This awareness can deter the preference adaptation. However, children are less likely to be aware of the fleeting nature of the standard of living and so are not protected from preference adaption in this way.

Lastly, the effect is going to be especially strong because the luxury gifts are provided for an extended period of time. If parents provide a luxurious standard of living for multiple years, that gives a very long time for the child’s preferences to be pushed upwards and solidify there.

On the flip side, the immediate utility effect is going to be smaller for children. The satisfaction people receive from luxuries often goes beyond the direct experiential joy of the good or service. There is also the novelty of the experience, the secondary reflective happiness from knowing that you are consuming something special. Children are much less likely to appreciate the novelty of the experience since they are likely, as argued above, to be less aware of the uniqueness of the experience.

In sum, luxury parenting has strongly negative preferencing screwing effects while it offers a limited positive immediate utility. In turn, luxury parenting is likely to have a negative expected net impact on children, meaning that luxury parenting is often impermissible.

Section 4: Objections

Objection 1: Symmetry Implications

If it is impermissible to give a luxurious standard of life to children, this could imply that it is morally required to give a miserable existence to children instead. If childhood suffering will push preferences down such that children will be happier in the long run, this may be better for the child. This implication would be so clearly unacceptable that it would condemn the whole argument. However, the implications of the model are asymmetrical. This is because children are generally thought to have significant rights, which ought to be respected. They have rights against being physically harmed and to a reasonable standard of living. Parents cannot impose suffering on their children even if it is a net-positive on lifetime wellbeing because this would violate these rights protections.

On the flipside, parents can permissibly withdraw these luxury goods, since children generally are not thought to have a right to luxury living.

Objection 2: Shared Time

One might argue that luxury parenting is permissible because it is necessary for parents to give themselves a high quality of life. Parents are generally thought to be under an obligation to spend quality time with their children because a healthy parental relationship is crucial for the child’s development. This is problematic since many opportunities for quality time are also opportunities for parents to spend money on themselves, such as restaurants, vacations, or entertainment. So, if we think parents should be permitted to spend money on themselves, this could make luxury parenting permissible. There are three responses to this objection.

Firstly, there are still many ways parents can spend on themselves without spending on their children. Parents can spend money on activities without their children or they can spend money on themselves while shielding their children from the same luxury expenditure, for instance by ordering a lobster for yourself and the pasta for your child.

Secondly, the magnitude of this sacrifice, being unable to spend on oneself, directly correlates with the level of wealth parents have. This makes the sacrifice a less significant problem because the wealth of parents reduces the required sacrifice of parenting significantly in other contexts. Wealthy parents can afford babysitters, summer camps, and meal boxes. This means that the sacrifice of giving up luxury is balanced out by the diminished sacrifice in other facets of parenting.

Thirdly, parents are routinely asked to make sacrifices for their children in determining how they spend their time. They can only watch child-friendly movies, avoid bars, and go to child-friendly holiday destinations. It’s unclear, for instance, how giving up luxury is materially different from forcing parents to go on vacation to Disneyland.

In sum, a parent’s interest in treating themselves is insufficient for making luxury parenting permissible.

Works Cited:

Bagenstos, Samuel R., and Margo Schlanger. ‘Hedonic Damages, Hedonic Adaptation, and Disability’. Vanderbilt Law Review 60, no. 3 (2007): 745–98.

Brighouse, Harry. ‘What Rights (If Any) Do Children Have’, 1 January 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199242682.003.0003.

Coleman, Joe. ‘Answering Susan: Liberalism, Civic Education, and the Status of Younger Persons’. In The Moral and Political Status of Children, edited by David Archard and Colin M. Macleod, 0. Oxford University Press, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199242682.003.0009.

Russell, Simon J., Karen Hughes, and Mark A. Bellis. ‘Impact of Childhood Experience and Adult Well-Being on Eating Preferences and Behaviours’. BMJ Open 6, no. 1 (1 January 2016): e007770. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007770.

[1] Bagenstos and Schlanger, ‘Hedonic Damages, Hedonic Adaptation, and Disability’.

[2] Bagenstos and Schlanger.

[3] Coleman, ‘Answering Susan: Liberalism, Civic Education, and the Status of Younger Persons’.

[4] Brighouse, ‘What Rights (If Any) Do Children Have’.

[5] Russell, Hughes, and Bellis, ‘Impact of Childhood Experience and Adult Well-Being on Eating Preferences and Behaviours’.

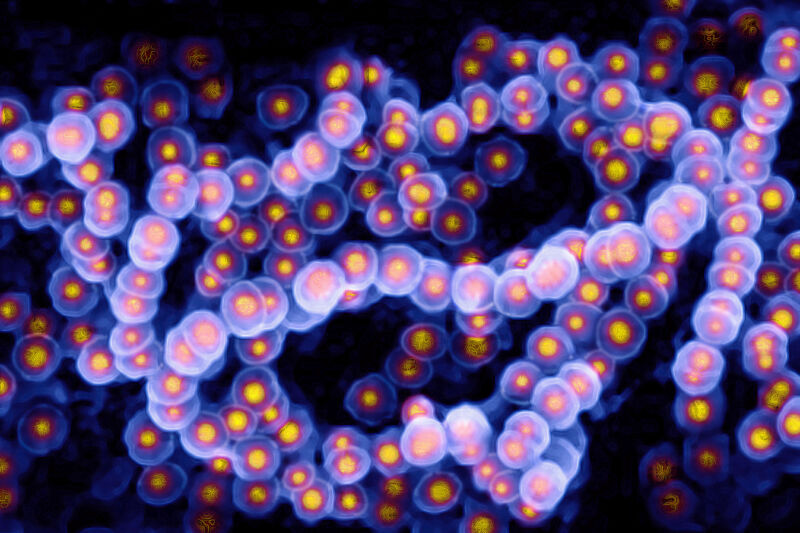

Enlarge / A microscope image of Streptococcus pyogenes, a common type of group A strep. (credit: Getty | BSIP)

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid a tall wave of respiratory viruses, health officials in Colorado and Minnesota documented an unusual spike in deadly, invasive infections from Streptococcus bacteria late last year, according to a study published this week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The spike is yet another oddity of post-pandemic disease transmission, but one that points to a simple prevention strategy: flu shots.

The infections are invasive group A strep, or iGAS for short, which is caused by the same group of bacteria that cause relatively minor diseases, such as strep throat and scarlet fever. But iGAS occurs when the bacteria spread in the body and cause severe infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease), toxic shock syndrome, or sepsis. These conditions can occur quickly and be deadly.

Here’s a wonderful sign I saw in a front yard while walking my neighborhood. This is exactly how I feel when I’m tossing out seeds at the beginning of a creative project: Are these weeds or are they flowers? I guess we’ll see.

But what is a weed? Emerson, ever a fan of a gardening metaphor, said it was “a plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.”

I came across another gardening metaphor just this morning: dandelions and orchids.

This metaphor comes from psychology and has to do with sensitivity in children. The idea is that some children are like dandelions and they can grow in any environment. Other children are like orchids: they need very particular conditions and the right environment to grow and thrive. And a majority of children are like tulips, somewhere in the middle of these two extremes.

The metaphor, like all metaphors, has limits, but I find it personally helpful: I’m raising one boy who’s more like a dandelion and one who’s more like an orchid.

Artists tend to be highly sensitive people, and I wonder how many grown artists consider themselves dandelions or orchids.

I feel like a dandelion, myself, which is good and bad. So often, I feel scattered to the winds, content to land wherever, and do my work there. I am easily distracted and can get interested in anything. Chaos can be a very fruitful source of creativity for me.

But there are orchid parts of me that I feel are really beautiful and often neglected — in part because I pride myself on my unfussy dandelion-ness.

I suspect this has some relationship to the specialist/farmer and generalist/hunter tension.