Recent philosophy-related news…*

1. Cornel West (Union Theological Seminary) is running for President of the United States for the People’s Party. Do check out the very Cornel West video announcement here. “Do we have what it takes? We shall see. But some of us are going to go down fighting, go down swinging, with style and a smile.”

2. Ian Jarvie, professor emeritus of philosophy at York University, has died (1937-2023). He was known for his work in the philosophy of the social sciences (he was the managing editor of Philosophy of the Social Sciences since its founding) and the philosophy of film. You can learn more about his writings here.

3. Elizabeth Anderson (Michigan) is one of the two winners of the 2023 Sage and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University (Sage-CASBS) award. The other winner is Alondra Nelson (Princeton). The award “recognizes outstanding achievement in the behavioral and social sciences that advances our understanding of pressing social issues” and the prize announcement calls Anderson “one of the deepest and most interdisciplinary thinkers in the academy.”

4. The Department of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame (ND) has hired four new faculty members: Alix Cohen (Edinburgh), who works on various aspects of Kant’s philosophy, will be Professor of Philosophy at ND this summer; Edward Elliott (Leeds), who works in philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, and metaethics, will be Associate Professor of Philosophy at ND as of Fall 2024. Jessica Isserow (Leeds), whose research is in metaethics, normative ethics, and moral psychology, will be Associate Professor of Philosophy at ND as of Fall 2024. Zach Barnett (NUS), who works in ethics, practical rationality, and epistemology, will be Assistant Professor of Philosophy this summer.

5. Some summer programs in philosophy are still accepting applications. Check out the programs for high school students, for undergraduates, and for graduate students and/or PhDs.

Discussion welcome.

* Over the summer, many news items will be consolidated in posts like this.

The post Philosophy News Summary first appeared on Daily Nous.

By Juergen Dankwort.

The proposal to provide assistance with voluntary assisted dying (VAD) has grown significantly over the past two decades at an accelerating rate. Right-to-die movement societies and organizations now number over 80 from around the world, 58 of which are members of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies. However, most are also increasingly beset with formidable challenges opposing their advances that raise profound ethical, moral and legal considerations.

The prevalent approach towards VAD

A review of these assisted dying regimes show how they were set up through legislative acts often resulting from initial court challenges to an existing assisted dying prohibition within that country’s criminal code. They reveal a common paradigmatic model whereby the criminal act remained intact with amendments added establishing a legislated framework to allow a service under specifically designated conditions and exempting the providers from punishment.

Generally, the legal criterion for accessing such a medically-centred service requires a person to be suffering intolerably from an existing, irremediable condition defined within legislated parameters, establishing who may access them, best practices, where and when they can be done, and who may perform them.

While not alone, Canada’s often-vaunted medically assisted dying regime (also known as MAID), implemented in 2016, is exemplary of this development with attendant massive challenges facing it. Its formulation illustrates an attempt to balance a previously court-declared constitutional right to life, liberty and security of the person with a perceived societal harm resulting from a state-sanctioned service to assisted dying.

Such legislated regimes have since been challenged legally numerous times by persons refused access, while featuring alarming stories in the media when access was sought and granted. A backlash to VAD has gained recent traction.

Traditional assisted dying opponents, including the orthodox religious, some disability groups, and conservative politicians who often troll to their populist base, are joined by additional academics and some physicians, providing more legitimacy with compelling arguments at stopping any wider access to a state-initiated and financially-covered national health service.

Germany breaks tradition

In a remarkable judgment by the German Federal Constitutional Court in February 2020, regarding assisted suicide, a ground-breaking option for any country or jurisdiction contemplating the creation of an assisted dying regime was identified that may well avoid much of the controversy and many of the challenges faced by existing ones. It does so by revealing a pathway to set up the service based on an entirely different orientation and approach from the existing one that began decades earlier in Europe, and later largely copied by others.

The German Court’s ruling stated for the first time that matters of quality of life and degrees of suffering are wholly subjective and that governments should therefore not prescribe nor proscribe assisted dying access based on categories of populations defined by such individually-experienced life-determinants because such restrictions would violate entrenched principles regarding personal autonomy and the liberal foundation separating state and personhood in pluralist societies. A VAD regime built on this premise could then also avoid all expressed objection to assisted suicide, no longer based on those normative criteria.

A recent study out of Europe contrasting two ways of how assisted dying services function, detail the actual process deciding for whom and when the service may be administered and who can perform it. The legislated regime of Belgium – a model used for Canada’s – was compared with the process in Switzerland.

Importantly, no legislated system was erected in Switzerland that specifies through amendments or exceptions how, when, by, and for whom it may be done. It has remained unlawful for decades with the simple caveat if it is done to exploit another vulnerable person. Several salient differences were observed by the researchers that also reveal the challenges presently facing existing VAD regimes. The Swiss model featured:

While claims that Canada has become the wild west for assisted dying with catastrophic consequences is arguably exaggerated given its stringent access requirements, it is nevertheless exemplary of a heightened political drama resulting from the path it took historically that set it on its stormy course.

That begs the question if the many countries and jurisdictions now considering a VAD gateway might not consider taking a different route illustrated by the current Swiss way, recently given a legal foundation by its European neighbour.

Though convincing evidence is still lacking on how expanding assisted dying allegedly leads to a slippery slope of harming the most vulnerable, as reported by some right-to-die societies and as shown in studies, opposition and barriers to it will likely invite more impulsive, desperate suicides that may traumatize and endanger friends, family, and first responders.

Author: Juergen Dankwort

Affiliations: Associate, University of West Virginia Research Center on Violence

Competing interests: Member, Right to Die Society of Canada; Supporter, World Federation of Right to Die Societies; Coordinator, Canada chapter, Exit International.

Declaration:

The author was not paid by any organization, group, government or individual in conducting research for and writing this article.

The post Overcoming impediments to medically assisted dying: A signal for another approach? appeared first on Journal of Medical Ethics blog.

The film critic Roger Ebert died 10 years ago today.

I came late to his work: I remember seeing him on TV when I was a kid, but I only really started reading him post-cancer, around 2010 or so, when he was in the middle of his great blogging explosion caused by losing his voice due to his health complications.

Something I wrote in 2011 about his blogging:

what makes Ebert such a brilliant blogger is that he’s doing it wrong—in the age of reblogs and retweets and “short is more,” he’s writing long, writing hard, writing deep. Using his blog as a real way to connect with people. “On the web, my real voice finds expression.” Man loses voice and finds his voice. “When I am writing my problems become invisible and I am the same person I always was. All is well. I am as I should be.” Blogging because you need to blog—because it’s a matter of existing, being heard, or not existing…not being heard.

He died while I was working on Show Your Work! and he has a whole section in that book called “You can’t find your voice if you don’t use it.” It might seem weird, but I thought the best way to start that book about putting yourself out there was to talk about death and what you do with your time — here was a writer who knew his time was short and he was sharing everything he could think of before he left.

One thing I’d like to call out that I don’t think a lot of people know is that Ebert was a writer who draws!

He wrote a blog post, “You Can Draw, and Probably Better Than I Can,” where he explained how he met a woman named Annette Goodheart in the early 1980s, who convinced him that all children can draw, it’s just that some of us stop.

He wrote beautifully about the benefits of drawing, how it causes you to slow down and really look:

That was the thing no one told me about. By sitting somewhere and sketching something, I was forced to really look at it, again and again, and ask my mind to translate its essence through my fingers onto the paper. The subject of my drawing was fixed permanently in my memory. Oh, I “remember” places I’ve been and things I’ve seen. I could tell you about sitting in a pub on Kings’ Road and seeing a table of spike-haired kids starting a little fire in an ash tray with some lighter fluid. I could tell you, and you would be told, and that would be that. But in sketching it I preserved it. I had observed it.

I found this was a benefit that rendered the quality of my drawings irrelevant. Whether they were good or bad had nothing to do with their most valuable asset: They were a means of experiencing a place or a moment more deeply. The practice had another merit. It dropped me out of time. I would begin a sketch or watercolor and fall into a waking reverie. Words left my mind. A zone of concentration formed. I didn’t think a tree or a window. I didn’t think deliberately at all. My eyes saw and my fingers moved and the drawing happened. Conscious thought was what I had to escape, so I wouldn’t think, Wait! This doesn’t look anything like that tree! or I wish I knew how to draw a tree! I began to understand why Annette said finish every drawing you start. By abandoning perfectionism you liberate yourself to draw your way. And nobody else can draw the way you do.

“An artist using a sketchbook always looks like a happy person,” he said.

(Come to think of it, I quoted some of those bits of him on drawing in Keep Going. So Ebert features in not one, but two of my books.)

Knowing that Ebert was a drawer means a lot to me, because, as far as I know, the only time our paths really ever crossed is when he praised my drawing of the Ross Brothers’ 45365 on his Facebook page.

I could go on — the “Roger Ebert” tag on my Tumblr is about 30 posts deep.

RIP to a great one.

This essay was originally published at The Rumpus on September 11, 2019.

I. Sister

For her twenty-first birthday, Kiều’s younger siblings set fire to her bed.

It was intentional, of course, and when she came home from work to find thick black smoke billowing out from under her shared bedroom door, as she stood before the remains of her pitted mattress crackling merrily in shades of red and gold, she wondered if it was time to leave at last.

This was a futile contemplation—they would have to murder her and roll her stone-cold body to a crematorium before she’d abandon them—but in the moment, her pulse leaped in time with the flames, her blood heated till she thought it might combust and melt her into fuel.

“Mai!” she screamed. The culprit could very well have been one of the boys, but no one was capable of stirring up trouble on the level of her little sister.

The pattering of plastic flip-flops reached her before Mai did. “Wow, Chị Kiều,” said Mai, tipping up her face to frown in mock concern. “You don’t look so good.”

Indeed Kiều’s eyes were blistering and tinged crimson from the smoke, and her teeth were bared in a twisting snarl. She stabbed a finger at the fire, which, while burning strong, was unnaturally contained to her half of the room. “Put it out.”

Mai pouted, though her almond eyes were gleaming in satisfaction. “I can’t put out something I didn’t start.”

Minh and Kỳ Lân materialized at the end of the hall, looking considerably more cowed at the sight of both sisters, one towering and furious, the other four feet tall and grinning. “Who?” Kiều snapped. “Which one of you little shits did this?”

Kỳ Lân, the second-oldest at fifteen, opened his mouth first to confess—which meant the culprit was quiet Minh, easily swayed and forever tucked under his older brother’s protection. “Minh,” she said. “Come here and put this out. Now.”

He shuffled forward, not meeting her eyes. The smoke parted around him, twined about his skinny legs but never touched, and when he raised his palms, still chubby with baby fat, the fire shrank as if it were a foal being coaxed, and finally sputtered out. “Sorry,” he mumbled in Kiều’s general direction. “I thought it’d be funny ‘cause we didn’t have candles or a cake.”

Kiều hadn’t the slightest inkling of how setting fire to her bed might come off as funny, but she was always softest on Minh—he so often had peculiar notions like these, and it never helped that Mai was there to play them to her advantage—and she’d just come off a ten-hour shift, and her weariness drove bone-deep. The smoke dissipated, inconsequential to their nonexistent alarms.

“Did you eat?” she said at last, addressing all three. The question was habit; it was comfort, a crutch; it signified home.

They all nodded.

“Homework?” It was a Saturday night, but a necessary follow-up. They nodded again. “Then go to bed.”

Kỳ Lân asked, “Where will you sleep?”

She glanced at Mai, at the anticipation and guilt warring across her little sister’s face. She knew Mai had hoped to get a night—tonight, of all nights—of sleeping alone. Minh’s pyromaniac idea had simply been a convenient tactic.

Kiều also knew she could repair her own bed with a wave of her hand and a bit of concentration. But she was exhausted, and her sister needed the space. “I’ll crash on the couch tonight. Go to bed now—we’re up early tomorrow.”

In the cold quiet of the living room later, unable to fall asleep, Kiều played with stars. A twitch of her fingers, wiggling them above her face the way an infant discovers its hands, and bursts of light perforated the darkness. Not exactly stars, in the astronomical sense; these were a multitude of colors, the shapes that swam across her eyelids when she rubbed her eyes too hard. Kiều watched them zing across the stucco ceiling. Tiny shreds of magic in a land otherwise devoid of it, a land intent on breaking down people like them. You had to seize such joys when you could. She liked to imagine the little powers they possessed had originated in the depths of an untamed jungle across the Pacific, where tigers ran rampant and spirits ruled the rivers and mountains, and a many-greats ancestor had been blessed or cursed with the ability to conjure fire and stars, and it had tracked their lineage across generations, across an ocean, to provide comfort in this lonely land. Immigrants who might lack in power of the institution, but whose veins ignited with an innate power all their own.

Down the hallway in their split room, Mai might have been doing the same—if she shared the same strange blood that ran in the others’ veins. Mai was their youngest sibling, of that there was no doubt, but she had never been able to raise or quell a flame, conjure sparks at her fingertips, drench a room with sudden rain. She blamed herself—no. She blamed Kiều. Especially on two particular days of the year: today, March 29, their father’s sixth death anniversary, and April 30, their mother’s third.

Kiều wasn’t around often enough to feel that blame directed at her. She blamed herself for that, too.

The photos taped on the wall above the couch crinkled and wailed as they sensed her sorrow. Only the two photos propped up on the altar in the far corner, one portrait for each parent, was framed. Pictures left to hang without barriers of glass or plastic tended to make more noise, audible only to their ears, and none of them could yet bring themselves to un-mute their parents.

“Shut up,” she muttered to the loose photos, and snuffed out the stars, and forced the sleep to draw to her like a rushing tide.

II. Younger Than

The temple was a sea of brown. Brown robes over brown skin over brown earth, from monks to nuns to regular Sunday devotees. The sea undulated with the pulse of the masses as people shuffled in and out between two meditation halls and the kitchens, chattering in rapid Vietnamese, bearing platters of homemade and temple-cooked offerings, discarding sandals at the doormats and thumping cushions on the bare wood floors. Usually Kiều would not have dragged all three children to Sunday prayers, preferring to leave them home and drop by before her shift to catch the final chants. But today’s weekly remembrance service would feature their father—and Mai knew her sister was nothing if not a dutiful daughter.

Mai bit down on her protests as Kiều shouldered a path through the crowd, instructing them all to keep their heads down. Orphans drew attention, invited sympathy. Especially at a gathering of a community with too little power and too much to prove. It’s on us to survive, Ma had said. Family means family and no one else. Subtext: dependence was a weakness when exercised outside the bonds of blood. Even Mai had understood that at eight years old. The only thing she didn’t understand was why Ma hadn’t brought her along to the supermarket that day nearly three years ago instead of Kiều, because Ma knew she was going to die, had possessed a terrifying ability to predict the time and place of a person’s death, and Ma knew Mai was not powerless, knew that her youngest daughter had been practicing bringing freshly dead little birds and mice back to life. But Ma chose Kiều—was always choosing Kiều, the hardest worker, the smartest student—and in the last desperate moments of her life, her oldest daughter was unable to save her after all.

By the time the four siblings found cushions in the back row of the meditation hall, Mai was throbbing with fury. The temple always brought this out in her. Maybe it was the constant battle of faith and loss exuded by the devotees’ breath, or the wall plastered with the wailing unframed portraits of late sangha members, or the simple fact that there was no escaping people in general. It wasn’t fair—her older siblings thrived off collective energy, siphoned threads of it to amuse themselves, perfectly at home in the community. Mai could only quash her irritability and anger, the effort blocking any possible concentration needed to resurrect even a fly. She was forever em, the younger and youngest, the pronoun connoting love but also less. Nothing she could do would ever measure up. Well—saving Ma’s life would have, but that chance, too, Kiều had stolen.

As she shifted to stretch out her sleeping feet she noticed a drop of condensation track its way across the floor. Minh brushed his index finger in an idle circle in front of his cushion, and the water answered, drawing from the exterior of cold bottles and the moisture in the walls, slowly pulled to the stirring of his finger. Kiều noticed. Said nothing. The monks leading the chant at the fore of the hall droned on and on.

Another time, Mai might have ignored them both. But yesterday’s attempt at getting Kiều to crack had been far from fruitful and the rising late morning heat broke her out in sweat and all she wanted was for Kiều to punish Minh as she would punish her, for life to finally be fair, and she was so, so close to boiling over.

Crowds and anger were blocks to her power. Fine. There were other cards to play. She was still a child, after all.

With a deep breath she threw back her head and let loose an ear-splitting wail. The intoning monks stopped short. The entire congregation twisted, still cross-legged, to stare at the little girl shrieking and weeping in the back. Kiều’s entire face blotched red. She snatched up Mai’s arm and towed her to the doors, smiling awkwardly and holding up a hand in apology, the boys hurrying after.

To Kiều’s credit, she waited until they were all piled in the battered family van before whipping around and screaming, “What’s wrong with you?”

Mai had ceased her display the moment the van door snicked shut. She glared at her sister, not knowing how to condense all her wild fraying thoughts into words on her tongue, not knowing how to say you’re not being fair, you don’t understand without sounding even more like the child she didn’t want to be.

So instead she yelled back, “I don’t want to be here! I don’t want this! I hate you!”

Kiều just clenched her jaw and faced forward and sat for a long, pregnant pause before turning the key in the ignition. The van was dead silent the whole way home.

III. Less Than

Kiều didn’t show her face at the temple for a month after Mai’s episode. And just like all the previous times when Mai had acted out in one way or another, she never brought it up again other than confiscating her dolls for a week. She had no idea how to prevent her little sister from pulling such stunts—in fact, she was fairly sure Mai no longer even played with dolls, but she had no other possessions to take away as punishment.

And so life continued as it had for the past three years. Kiều went to work, six and a half days a week. She’d gotten her AA in accounting from community college last year, and was always meaning to apply for a bachelor’s program, but there were endless bills to pay even though the mortgage itself had been covered before Ma died, and how could she leave her siblings even more alone?

Once every so often a well-meaning woman from the temple would call her, offering to babysit or inviting them to birthday parties. Kiều always declined, politely. She enjoyed being around other families, but she had also been raised to be self-sufficient. Slacking on responsibility was not, would never be, an option.

Their little house was quiet—subdued—for the next weeks, until one Friday night Kiều returned to find a large shaggy dog loping about the living room, barking like mad as the boys laughed and tossed it bits of last night’s beef.

“Mai!” she yelled immediately. “What is this?”

To her shock, Mai dashed out of their bedroom with a wide grin that was pure elation, no malice. “Chị Kiều! Look what I did!”

“What’d you do? Where’d this dog come from? Why is it—”

“His name is Tiger, and look at his left side!”

The dog slid to a halt before her, panting happily. She leaned over to peer at its side and almost gagged. There, sunken in and nearly concealed by its shaggy black fur, were undeniable tire marks of reddish-pink skin. She looked up at her little sister in horror. “Explain.”

“I’ve been practicing for years—just the little sparrows I find in the front yard sometimes, and one time a mouse—”

“Practicing … on dead animals?”

“I’m not powerless!” Mai cried in joy. “I can do what all of you can!”

“None of us can bring back the dead,” said Kiều, even as her mind whirred, dredging up terrible memories she’d worked so hard to bury—the car ride, the final words—

Mai was already frowning, withdrawing, sensing her older sister’s distress rather than the astonished pride she had hoped for. “Well, I can,” she snapped. “I found Tiger down the street coming home from the bus and Minh helped me drag him back and Kỳ Lân got home and screamed a little but I did it, I saved his life!”

“Dead things are meant to stay dead,” hissed Kiều. “We don’t understand how our own powers work—what if it took your life to revive it? How do you think I’d feel, coming home to find you dead or hurt over a dog?” Fat tears brimmed over Mai’s eyes, but Kiều drove on. “Don’t try this again. Kỳ Lân, go put the dog outside. It probably wants to go home to its family.”

“No!” screamed Mai, but Kỳ Lân silently rose and herded the dog to the door. There was no arguing with Chị Kiều when it came down to it. Fear forbade it; hierarchy permitted fear. Mai and Minh and Kỳ Lân were all little siblings after all, em to chi, loved but still lesser.

Mai let out a shriek of helpless fury. “You’re always taking things away from me!”

They all dispersed to separate corners of the house after the dog was gone.

This time, the stars were ice. Frost webbed over Kiều’s hands as she manifested the miniature stars, again sleeping on the couch to avoid Mai’s temper, and she welcomed the bite. She considered making up with her sister by getting a real dog from the pound and immediately dismissed the idea—there was no way she could afford another mouth to feed.

Was this destined to be her life? Was she doomed to play guardian to three children who weren’t hers, not exactly, until they grew up, if they grew up? They weren’t an American family, even if their passports, bound in neat navy blue after Ma and Ba passed the citizenship test, said otherwise; she couldn’t just kick them out once they turned eighteen.

A twinkling shard of ice, illuminated from within by a heatless red light, fell on her brow. She brushed it away irritably. A traitorous shred of her heart jumped at the color, even if it wasn’t the exact shade she had come to fear.

Three years ago, that icy winter day, shifting in the passenger’s seat as Ma raced down the highway to get to the supermarket before closing, Kiều’s hands had glowed red. It was sudden—one second she was staring out the window and in the next she’d glanced down and shrieked, because the only other time her palms had shone that violent crimson was when Ba was in the operating room and five minutes later the surgeon had walked out with somber, pitying eyes. Ma looked over at Kiều’s hands and an inexpressible sorrow had clouded her gaze.

“There’s a reason for everything, con,” she’d murmured to Kiều. “I can see a lot of things, most of them things I don’t want to see, but there’s no preventing what’s meant to happen.”

“Ma,” said Kiều, a sick feeling ballooning in her stomach. “What do you mean?”

Ma only gave her a small, weary smile. “Con, nhớ chăm sóc em nha.”

My child, remember to look after your little siblings.

And then the car slipped on ice to the left, into opposing traffic, and the ringing went on forever.

Lying there beneath the twisted metal, Kiều had believed she was paralyzed. But that was only the shock, the doctors told her after, because she’d escaped with not a scratch on her body. She’d never broken a bone or experienced a major injury before in her life—she’d never had an opportunity before the crash to realize she was unbreakable.

Now, with floating ice dotting the living room ceiling, her head spinning years away, Kiều squeezed her eyes shut and tried to think of nice things, bland things, anything to drive away the memories: electric bills, grocery lists, Sunday pizza nights, upcoming birthday gifts—

You’re always taking things away from me.

In the chaos of the dog, that particular cry had gotten lost. Of course, Mai had meant the dog, or the dolls that had been confiscated—

Kiều recalled how Mai had begged to go to the grocery store that day, how Ma had refused with a firm and knowing glance, had chosen Kiều instead. And Kiều had turned out to be unbreakable, but Mai—Mai had turned out to be a resurrectionist.

Ma had known. Said nothing. What was more, Ma hadn’t needed to bring anyone with her in the car, if she’d known she was going to die.

The great family arsenal of guilt, ancient and brutally effective. Kiều had been drawing from the seemingly bottomless well of it ever since that day. Had used it to keep herself working, praying, moving at all times; had used it to maintain that distance between herself and her little siblings. Nhớ chăm sóc em.

She sat up and got to her feet.

There were things that needed to be said.

***

Rumpus original art by Dara Herman Zierlein.

***

A note on Vietnamese pronouns: Chị is used to address an older sister or general older woman. Em is more versatile, and can be used to address a younger sibling or general younger person (regardless of gender), though it does tend to carry a connotation of femininity. It can also be used to show affection (a boyfriend to a girlfriend, for example) or to call out a person’s lesser status in a social hierarchy.

Maria Rosa Antognazza, professor of philosophy at King’s College London, has died.

Professor Antognazza was known for her work on the history of philosophy, particularly Leibniz, philosophy of religion, and epistemology. She is the author of, among other things, Leibniz: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2016), Leibniz: An Intellectual Biography (Cambridge University Press, 2009), Leibniz on the Trinity and the Incarnation: Reason and Revelation in the Seventeenth Century (Yale University Press, 2007). Another book, Thinking with Assent: Renewing a Traditional Account of Knowledge and Belief is due out from Oxford University Press this year.

You can learn more about her research here and here.

Professor Antognazza joined King’s College London in 2003. Prior to that, she was a member of the philosophy faculty at the University of Aberdeen. She earned her PhD in philosophy from Catholic University in Milan. She was the current the chair of the British Society for the History of Philosophy (BSHP) and a recent president of the British Society for the Philosophy of Religion (BSPR)

According to a memorial notice published on the King’s College London philosophy department page, Professor Antognazza died on Tuesday, March 28th, after a short illness. In a memorial notice at the BSPR site, she is remembered as “a brilliant and learned philosopher, kind and sensitive, and always so energetic and generous.”

Her funeral is to take place on Friday March 31st, at the Holy Road Catholic Church, Abingdon Road, Oxford, at a time to be confirmed.

You can listen to an interview with Professor Antognazza here.

UPDATE: Readers may be particularly interested in Professor Antognazza’s article, “The Benefit to Philosophy of the Study of Its History” which appeared in the British Journal for the History of Philosophy in 2014 (ungated version downloadable here). In it, she says:

The history of philosophy should be both a kind of history and a kind of philosophy, and that its engagement in genuinely historical inquiries is far from irrelevant to its capacity to contribute to philosophy as such. As a kind of history, the history of philosophy must meet the standards of any other serious historical scholarship, including the use of the relevant linguistic and philological tools, and the study of the broader political, cultural, scientific, and religious contexts in which more strictly philosophical views developed. As a kind of philosophy, however, its ultimate aim should be a substantive engagement with those very philosophical views—first, in striving to understand them on their own terms, and secondly, in probing and interrogating them as possible answers to central questions of enduring philosophical relevance.

Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg received a threatening letter that said, ""ALVIN: I AM GOING TO KILL YOU!!!!!!!!!!!!!" along with white powder today, according to NBC News. The death threat comes on the same day Donald Trump warns on Truth Social about "potential death and destruction" if he's indicted. — Read the rest

Wayne J. Froman, associate professor of philosophy at George Mason University, has died.

Professor Froman worked in 20th Century Continental philosophy, especially phenomenology and figures such as Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Emmanuel Levinas, and Franz Rosenzweig, as well as philosophy of art. He is the author of Merleau-Ponty: Language and the Act of Speech (1982), among other works, about which you can learn more here.

Professor Froman joined the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at George Mason University in 1985. Prior to that, he taught at the New School for Social Research, Marist College, and SUNY Potsdam.

In a memorial notice on the George Mason website, Froman’s colleagues remember him as a leading scholar in his area and an inspiring example for his students, recalling his intelligence, sense of justice, and humor.

There is also a brief memorial notice here.

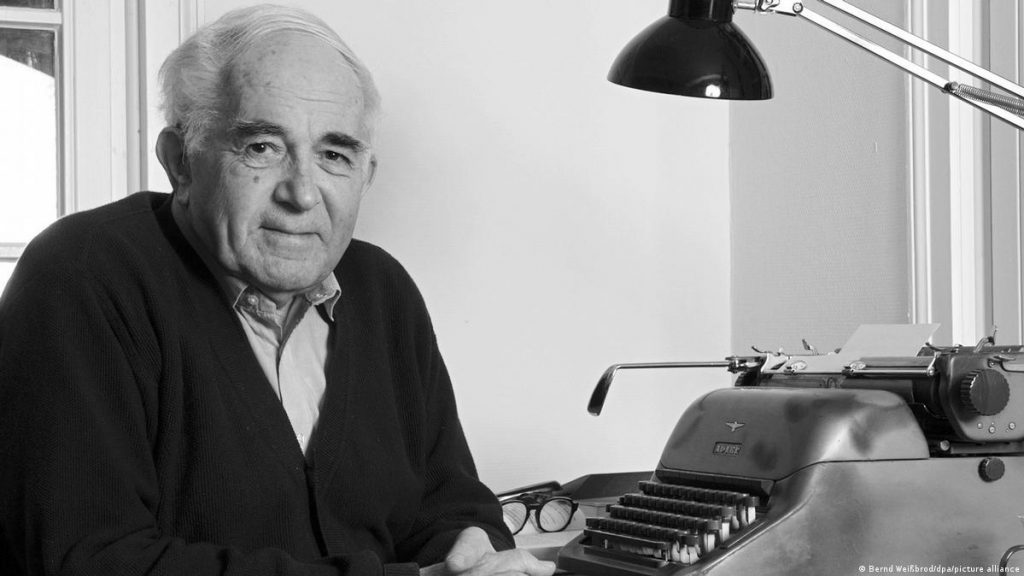

Ernst Tugendhat, an influential German philosopher who taught at the University of Heidelberg, the Free University of Berlin, and other universities, has died.

The following memorial notice was written by Stefan Gosepath (Free University of Berlin).

The philosopher Ernst Tugendhat (1930-2023) died on March 13, 2023. Tugendhat was an eminent contemporary German philosopher who made important contributions to re-establishing analytic philosophy in Germany after the Nazi era, when almost all analytical philosophers had had to leave.

At the same time, Tugendhat distinguished himself as an intermediary between continental and analytic philosophy.

Trained by Heidegger in the Aristotelian and phenomenological traditions, he offered original arguments to show that analytic philosophy of language is the culmination of Aristotle’s ontological project. In his systematic, historically-oriented treatise on (analytic) philosophy of language (Traditional and Analytical Philosophy, P.A. Gorner trans., 1982), he bridges the gap between continental and analytic ways of philosophizing.

In response to the tradition of the so-called philosophy of consciousness, Tugendhat applies linguistic analysis to explain the problem of consciousness of the self (Self-Consciousness and Self-Determination, P. Stern trans.,1986). He argues that Wittgenstein’s view of self-knowledge and Heidegger’s account of practical self-understanding are intrinsically connected, because one is only conscious of oneself when one asks what kind of human being one aspires to be. This self-addressed question is also central in Tugendhat’s conception of ethics: for him, morality is justifiable only in relation to conceptions of the goodness of the self. His lectures on ethics (Vorlesungen über Ethik, 1993), in which he developed his ethical views, are considered the most significant contribution to German systematic moral philosophy of their time alongside the discourse ethics of Apel and Habermas.

Born into a Jewish family in Brno, Tugendhat emigrated to Venezuela; he received his BA at Stanford in 1949, his PhD at Freiburg in 1956, and his Habilitation at Tübingen in 1966. He held professorships in Heidelberg, Starnberg, and Berlin.

UPDATE (March 19, 2023): German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier sent public condolences to Tugendhat’s sister, Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat, calling him “one of the most important philosophers of the post-war period, whose thinking revolutionized and shaped German philosophy.” You can read the whole statement here. (via Christian Beyer)

Readers interested in learning more about Professor Tugendhat’s writings can browse some of them here and here.

Obituaries elsewhere:

Stephen and Rae Ann Gruver said the funds from the verdict over their son’s death would help support the mission of the Max Gruver Foundation, an organization committed to ending hazing on college campuses.

Jitendra Nath “J.N.” Mohanty, professor emeritus of philosophy at Temple University, has died.

Professor Mohanty was well-known for his work on phenomenology (especially Husserl), Kant, and Indian philosophy. He is the author of, among other works, Between Two Worlds: East and West, an Autobiography (Oxford University Press, 2002), Classical Indian Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2002), The Self and its Other (Oxford University Press, 2000), Logic, Truth, and the Modalities (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999), and Phenomenology: Between Essentialism and Transcendental Philosophy (Northwestern University Press, 1997), Husserl and Frege (Indiana University Press, 1982), and Edmund Husserl’s Theory of Meaning (Springer, 1976). You can learn more about some of his writings here.

Prior to taking up his position at Temple, Professor Mohanty taught at various institutions, including the University of Burdwan, the University of Calcutta, the New School for Social Research, the University of Oklahoma, and Emory University. He earned his PhD at the University of Göttingen, and his MA and BA at the University of Calcutta.

He died on March 7th.

(via Malcolm Keating)

Anne Fairchild Pomeroy, professor of philosophy at Stockton University, has died.

The following memorial notice was provided by Peter Amato (Drexel University).

It is with profound sadness that I share the news of the passing of Anne Fairchild Pomeroy, Professor of Philosophy at Stockton University.

A legendary teacher and mentor at Stockton, Anne developed and taught courses that expanded the breadth of her program and her students’ horizons dramatically, including Critical Social Theory, Modernity and its Critics, Process Philosophy, African American Philosophy, Feminist Theories, Philosophy of the Other, Power and Society, Existentialism and Film, among others. She created and co-taught a highly successful course on Marxism and Economics with a colleague from the Economics program.

Anne’s scholarship was focused on social justice, and she produced scores of articles, conference presentations and the acclaimed book, Marx and Whitehead: Process, Dialectics, and the Critique of Capitalism, over the course of a long and successful academic career.

Anne was also an accomplished classical flute player, and performed on multiple instruments and sang with the Stockton Faculty Band for twenty years.

She served as Stockton Federation of Teachers Union President from 2012-2017, guiding the local through some of its most challenging times and complex negotiations. She said the Union was not an organization, but “a way of being in the world that we have chosen with each other.”

When I met Anne in the early 1990’s she had just arrived at Fordham from Columbia, in search of philosophy and philosophers who weren’t just interpreting the world. The community of scholars and activists she gathered around her provided what she had been seeking in an academic career and in her life. For Anne, the quest to be part of and help create such a community as an educator, philosopher, and activist was the work of her life, a life well lived and with great success.

But in the background for most of her stellar work Anne was fighting a battle with breast cancer, its effects, and the effects of its treatment. She defeated breast cancer, but not long after developed the endometrial cancer that would be fatal.

In the days since her death there has been a tremendous outpouring of admiration and sadness from students, colleagues, friends, union staff and rank-and-file, band-members, and others who knew Anne sharing stories and expressing their love for her and feeling of loss. In her research, her music, her activism, and her life, Anne always sought to build others up through connection and compassion. She will be remembered for her kindness, her intelligence, and her passionate advocacy for justice. In lieu of flowers or cards, please consider donating to your local SPCA, shelter, or farm animal sanctuary.

Stockton University will hold a remembrance and celebration of Anne’s life on Monday, March 20 on campus that can also be seen via Zoom. Please contact me if you would like further details: [email protected].

An obituary for Professor Pomeroy has been published in The Argo.

Huenemann

This story was funded by our members. Join Longreads and help us to support more writers.

Maria Zorn | Longreads | March 7, 2023 | 3,373 words (12 minutes)

In middle school, I would hide behind a giant oleander bush when it was time for the bus to leave for track and field meets and then, once it left without me, I’d walk to Panda Express and eat chow mein in blissful peace. This was also my strategy for grieving you. I thought I could, like a rapacious vole, burrow myself into the branches of the quotidian and the bus of mourning would pass me by altogether.

This is not to say that I didn’t ever experience a sense of loss. It was always there, a constant drip. Sometimes I’d think about the scene Mom came upon when the locksmith finally got your apartment door open and feel as though my kneecaps were going to crumble into ash beneath me. I wondered if there were claw marks on the floor from where you tried to stay as you felt your heart stop beating, or if you slid easily away like a clump of lint and dog hair into a Roomba. In these moments I wished to be vacuumed whole.

* Name and location have been changed for privacy.

Sophie works at the post office in Saanichton, British Columbia.* She is tall and sinewy with thin, bony shoulders. Her body could be drawn using only straight lines, just like yours. Her hair is jet black and always pulled back into a low ponytail that nestles into the nape of her neck. She appears to be more at ease when she is behind the counter than when she is in front of it, exposed. Her voice is low and quiet and when she gets flustered she holds her elbows close to her rib cage and her hands near her shoulders like an adorable T. rex. Her mannerisms are what initially drew Mom to her, what first reminded her of you. But then she saw her protruding clavicle and her thick top lip and her round doe eyes and she couldn’t unsee the physical resemblance. She wants me to help her think of a way to befriend Sophie that doesn’t begin with: You remind me of my dead son and I would do anything to spend time with you. I just don’t know what to tell her.

Perhaps the better metaphor is that my grief for you stalked me like those ghosts in Ms. Pac-Man. I was chasing dots with my mouth wide open, trying to outrun you. The dots were moments I still felt some semblance of myself in a world without you in it, they were anyone and anything that could drain me of all of my energy and attention, they were being able to feel light enough to giggle, they were attempting to Irish dance while waiting for my tea kettle to whistle. The ghosts were you, at 8, declining to go on a playdate because you were afraid I wouldn’t have anyone to play with; you, at 16, threatening to hit the boy who broke my heart with your car; you, at 22, telling me we were soulmates with tears in your eyes at the Molly Wee pub; the ghosts were you, you, you, you with pastel sheets over your head, cutouts for your big Bambi eyes.

Mom gets butterflies in her stomach before she goes to the post office. She’s glad for once that she has a P.O. box, that the mail carrier doesn’t come to her mossy, rural strip of the Saanich Peninsula. She blow-dries her light blonde hair until it falls in cascading curls around her face and blinks on mascara. She pulls on her stylish brown leather boots and steals one last look at herself in the mirror. She takes a deep inhale that tickles the pain in her chest. Mom wants to be more than friends with Sophie, but not in the traditional sense of the phrase. I loved you like a soulmate, but not in the traditional sense of the phrase. These loves are fluid, these loves are nonbinary.

* Name has been changed for privacy.

The dots I chased were Chris, because every emotion I felt with him was neon.* We slept glued together like spider monkeys, and when I woke up before him I would be completely still and study him worshipfully — his toffee-colored skin that was softer than a kitten’s ear, his charcoal ringlets. We watched videos of Thom Yorke dancing for hours at a time, we did a special little jig when we bought a bottle of puttanesca sauce. When I was sad, he’d get out a Japanese sword that was left at the bar where he worked and throw watermelons in the air for me to slice like a fruit ninja. He could make anything fun, could make anything a game — but he was always the team captain. I was never certain whether it was our 14-year age gap or simply his personality, but he felt as much like a coach as he did a boyfriend. I thought he shut me down when I disagreed with him and I knew he blew his nose in our dirty laundry, and these things both made me furious. Two years passed and we morphed into ever uglier versions of ourselves. We yelled at each other outside of Joe’s Pizza by the Slice, he was a gargoyle and I was a swamp lizard and then we were two terribly sad people who didn’t talk anymore. For months after we broke up, I lay in bed every night, crusty with dried tears and snot, and my ribs felt loose. I imagined Chris playing Radiohead songs on them like they were piano keys while I tried and failed to fall asleep. I was convinced that if I concentrated hard enough on my heartache for him that I would not notice how hollow I felt from your goneness.

You wore six-inch platform creepers and voluptuous shaggy Mongolian lamb coats, Rick Owens pencil skirts and black leather fingerless gloves. You ordered a floor-length sheer dressing gown with sleeves trimmed in feathers. When Mom said she liked it but it looked like something one would wear over a négligée, you earnestly replied: But I don’t have a négligée yet! Before I moved to New York with you, I came to visit and had to use my tube top as a pillowcase since you owned only one. I cleaned your apartment while you scoured town for a fake ID for me, an even trade. After sweeping the 600-square-foot space I had a chinchilla-sized pile of dust and boa fragments and sequins and dirt and I felt like Cruella de Vil’s housekeeper. You made a fool of the words “feminine” and “masculine” — you were neither, you were both. You called yourself an alien frequently, and even got one tattooed on your right arm. You felt like you were so different from other humans that you were extraterrestrial. No one we knew used they/them pronouns, no one we knew used terms like “nonbinary,” like “gender-fluid.” You knew you didn’t identify with other men, but you also knew you didn’t feel like other women. I wonder if you would have felt like such an alien if you knew you didn’t have to choose. I wonder if you would have tried snorting heroin that night if you didn’t feel like such an alien.

My dots were my budding career at a tech startup that I thought was so much more impressive than it actually was. I worked from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. then came home, ate noodles, propped my laptop on the pudge of my lower belly, and kept working in bed until I fell asleep. I tried dating during this phase, but I got more pleasure from telling men I was busy and then later breaking things off than I did from going to dinner with them.

My eyes began to tolerate all of the computer work I was doing less and less until it felt like all that occupied my sockets were two purple bruises covered in fire ants. After trips to six different ophthalmologists, I was diagnosed with non-length dependent small fiber polyneuropathy and ocular rosacea and told that a career that involved “excessive screen time” was probably not in the cards for me. The doctor looked at me with a very serious expression that was made less serious by a small piece of avocado that clung to his mustache. I was such a people pleaser that in this moment all I could think of was making this a smooth experience for him so that he didn’t go look in the mirror after our conversation and feel like an idiot for having a dirty ’stache. This was a time in my life when if someone gave me a ride, I’d offer them a kidney. I jammed the shock and anguish I felt into the depths of my pockets alongside pennies and crescent-shaped nail fragments, I arranged my face into an awkward smile and said: No worries!

I wonder if you would have felt like such an alien if you knew you didn’t have to choose.

I quit my job and the online college courses I was taking and returned to bartending with the enthusiasm of a wet tube sock. An overly cheerful woman with a hair growing from the mole on her chin asked me to surprise her with a drink and I poured well rum and apple juice into a pint glass with no ice then charged her $13 for it. I didn’t talk to my friends who were graduating and starting careers, I stopped dating. I closed in on myself and got smaller and smaller until, like a Shrinky Dink, I could be pierced and worn on a string as a hideous pendant.

I had moved back home to Arizona after you died because I couldn’t stay in New York City without you. The ghosts were too speedy there, but the dots were too far apart in Phoenix. I needed to get out. I applied for a sales position in Denver that promised not to involve the computer, packed my belongings into my beat-up red hatchback and took myself to Colorado. Driving through mountain passes, I felt an indelible sense of hope that this change of scenery would make me better, whatever that meant.

I watched the video you recorded six months before you died yesterday, the one where you’re drinking Veuve with your friend Michelle and explaining what you want done with your ashes if anything ever happens to you. You throw your head back to cackle between your outlandish requests and I stare at your pale throat. Some ashes stored in a Ming vase, some made into diamonds, some shot out of a cannon with glitter. Mom and I looked into the cannon, but all we could find was some silly handheld thing called the “Loved One Launcher” that appeared to be used primarily at memorial services held next to creeks and swamps, judging from their marketing material. It definitely wasn’t the right fit.

We didn’t know how to “memorialize” someone who felt as essential as a limb. In our indecision, we landed on taking a trip someplace beautiful every year on the anniversary of your death. We’ve been to Cabo San Lucas, Aspen, Copenhagen, Sooke. We split a bottle of rosé and hold hands and your absence is outlined in chalk on the picnic blanket we sit on. Once, we hiked 13 miles to a beautiful alpine lake to scatter some of your ashes and I carried them on my back. I had only your remains and a bottle of wine in my pack but the straps dug into my shoulders until they were pink as salmon. We sang “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” by the Hollies and laughed and cried at the same time. When we dumped your ashes in the water they shimmered in the sun like the glitter you wore on your eyelids and cheeks during your teen raver years. I wanted so badly to look up at the sky that was the same blue as your eyes and feel unadulterated solace, but instead I felt nothing at all.

This year on May 30, I think Mom is going to take me to the post office.

My dots were jobs, jobs, new jobs every few months. I worked as a kiosk wench for HelloFresh, a sales manager for StretchLab, a preschool teacher at a country day school, a fitness instructor at Life Time, at a physical therapy clinic, at a Pilates studio. I went back to school to become an art teacher, then quit that and took a yearlong nutrition course, then decided I never actually want to talk to anyone about what they eat. I remembered once hearing the phrase “throwing spaghetti at the wall and seeing what sticks” and I imagined myself doing parkour off the furniture at each of my jobs, shooting noodles and marinara out of my fingertips and watching the pasta bounce off of the reformers, the little children, the clinic walls like rubber. I had eaten all of the dots in the maze and was left aimlessly bumping into its corners with a jaw ache, desperately trying to avoid a ghost pileup.

I had a dream that I was walking around a city map, but the map wasn’t made of paper — it was a black iPhone, the glass so shattered it looked like it was filled with streets and boulevards. All the roads filled with white powder until I couldn’t move my legs anymore. The phone was yours, and it sat next to a full pour of wine, murky reddish-black like blood. You died sitting up — bony ass on the floor, back against the side of your bed, pale slim fingers wrapped around your glass. How did you manage not to spill one drop? Why did you think heroin was a suitable nightcap after cocaine, Adderall, alcohol?

I remember sitting on the back porch of Mom’s house with you every night one summer, talking and smoking hookah for hours until the metal patio chairs branded the back of our sweaty legs with checkers. Even at 10 p.m. it was over 100 degrees in Phoenix. I’d feel droplets of sweat crawl from my armpits down my sides and settle into the waistband of my boxer shorts. We’d put a splash of milk in the water pipe because you were convinced that would make the smoke cloudier, more fun to blow O rings with. You confessed one of these nights to smoking black tar heroin once during your sophomore year of high school, when you were a self-proclaimed “mall goth.” I whapped you with the wooden hookah mouthpiece, hard, right in the solar plexus. I thought about the time we gobbled up so many of Dad’s prescription drugs and drank so much prosecco that we blacked out an entire journey from Amsterdam to Phoenix, including a three-hour layover that was apparently in Detroit, judging from the translucent blue lighter we bought that said Motown City and the greasy Little Caesar’s receipt that sat cross-legged in the bottom of my purse. I was not prudish about getting fucked up, but with this anecdote you crossed a threshold into territory that scared me. You took a sharp inhale and raised your dark eyebrows, fighting back a laugh. You said: Obviously that was dumb and I’ll never try it again. I made you promise with a pinkie, even though you were 19 and I was 17. Your recklessness with your life produced in me a worry that sat like a small, hard stone in my belly.

You’d hate the way dying from a heroin overdose sounds. You’d have me let everyone know that you were “trying to buy opium.” That you were supposed to go to a wedding in Greece in two months, New York Fashion Week in three. That you didn’t mean for it to happen this way.

The dots were gone, but I became so adroit at ghost evasion I no longer needed them — I was eating strawberries, oranges, bananas, cherries. I found a drug that makes my eye condition more tolerable, a job I like well enough, a dog who constantly wants to shake my hand. I found a partner with Reptar green and caramel eyes who gives me grace like a daily train ticket, who calls you Tomm, not “your brother,” whose calm demeanor lowers my blood pressure and provides a certitude that life is allowed to feel good. I thought Jack’s love was a fuzzy sweater I could don and become whole. I saw no portents of a more substantial ghost, one that could swallow me entirely. I fell into the mouth of a ghost as though it was a shoddy manhole cover; it took me by surprise and then devoured me until I was wholly in its maw and could not see a single shred of light through its incisors. My grief developed its own physical presence, its own pulse. I feared that it was going to burst through my bones like the Kool-Aid man at any moment and take me over completely. My first instinct was to wrestle it to the ground, to mash my teeth into its ears and give it a noogie, since I was always the brute of the family. I knew you’d try to reason with it, to write it a letter using your shiniest vocabulary like the ones you’d send to Mom and Dad to convince them to raise our allowance, to get a pet sugar glider, to let you get your ears pierced, to legally change the “Jr.” that follows your name to the more sophisticated and chic “II.” You’d arrange all of your best arguments like toy soldiers followed by rebuttals of anticipated counter-arguments, then sign: Please don’t be mad at me. As a card-carrying atheist I didn’t know who to write a letter to. The universe? You?

I loved you like a soulmate, but not in the traditional sense of the phrase.

My therapist recommended I try ketamine for treatment-resistant depression and I had my first session this week. I thought of you because the first time I heard the word “ketamine” was when you snorted it in ninth grade and then came out to Mom, and the first time I heard the term “treatment-resistant depression” was after I talked about you to my therapist, seven years after you died. I filled out a questionnaire that tests for suicidality and it was only then that I realized my sadness had become life-threatening. I had a primordial urge to go wherever it is that you are. I’d sign my note to Mom and Jack: Please don’t be mad at me.

The nurse anesthetist injected the drug into my shoulder and it felt like a gentle bee sting. There were colors and textures and sounds that I can’t explain, but what I remember most of all was you. Your hair was dyed platinum blonde and a thin white shirt hugged your angular frame. You were resplendent. You were laughing and reaching out for my hand, and I chased you across tiles that lit up under our feet as we stepped on them. We knew you were not alive but we also knew that you were not gone. Looking at you, for the first time in seven years, didn’t feel like gazing directly into a car’s headlights at night; you didn’t singe my delicate eyes with your brightness. You hugged me the way you always did, so tightly that your upper ribs jabbed into my torso with a titty-puncturing ferocity, like you were holding on for dear life, and I felt an ineffable sense of something inside me being cauterized. Later I’d recall a mathematical concept from high school in which two lines get very, very close together but never actually end up touching and wonder if, for me, this would be the closest I’d ever get to feeling peace about your death. As I began to regain consciousness, your face became pixelated and the crinkles around your eyes started to smoothen and fade. The first part of my body that woke up was my mouth, and I could feel my chapped lips pressing together with alacrity to form a small smile. Before you disappeared completely, you said: What if it’s all true at once? You held those words up like a trophy and I unzipped my chest and put them inside.

Maria Zorn is a writer and visual artist currently living in Denver, Colorado.

Editor: Cheri Lucas Rowlands

Copy-editor: Krista Stevens

Charles H. Kahn, professor emeritus of philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, has died.

The memorial notice, below, was provided by Michael Weisberg, chair of the Department of Philosophy at Penn.

Charles H. Kahn, one of the most important historians of philosophy in the last century, has passed away at the age of 94. Kahn’s books and articles on ancient Greek philosophy, particularly on the Presocratics and Plato, are landmarks in philosophical and classical scholarship.

Born in Louisiana, United States of America, in 1928, Kahn enrolled in the University of Chicago at the age of sixteen, where he completed his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees. After further study at the Sorbonne, he completed his doctorate in classical studies at Columbia University, then served as Assistant and Associate Professor of Classics at Columbia from 1958 to 1965. He was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania in 1965, where he remained until his retirement in 2012. In addition to serving as chairman of that Philosophy Department, he held visiting appointments at other major universities, including Harvard, Cambridge, and Oxford.

As a leading scholar in his field, Charles Kahn served as editor or on the editorial board of several philosophical journals, as President of the Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy (1976-8), as Vice President of the American Philosophical Society (1997), and was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2000). His many honors include major research grants from the American Council of Learned Societies (1963/4 and 1984/5), the National Endowment for the Humanities (1974/75 and 1990/91), and the Guggenheim Foundation (1979/80).

While he wrote widely in ancient Greek philosophy, his focus was especially on Presocratics in the early decades of his career and on Plato in later decades. His doctoral dissertation, which was published as a book, Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology (Columbia University Press 1960), was a groundbreaking contribution to the study of pre-Socratic philosophy and is still unsurpassed today. His other books on the Presocratics include The Art and Thought of Heraclitus: An edition of the fragments with translation and commentary (Cambridge University Press 1979), still widely admired among literary and philosophical scholars, and Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans. A Brief History (Hackett, 2001), which was aimed at a wider audience.

In 1973 Kahn published the monumental work, The Verb “Be” in Ancient Greek (Reidel, Dordrecht), in which he systematically studied all the uses of the verb “to be” in ancient Greek literature from Homer onwards, discovering uses and subtle nuances that had escaped the attention of scholars. The book continues to have a significant impact on our understanding of ancient Greek language and philosophy. It provoked numerous debates and responses over the years. In 2009, Oxford University Press published a collection of Kahn’s articles in reply to those responses, in a volume entitled Essays on Being.

Kahn’s enormous contribution to the study of Plato’s philosophy lies particularly in two important books. Plato and the Socratic Dialogue (Cambridge University Press 1996) and Plato and the Post-Socratic Dialogue: Return to the Philosophy of Nature (Cambridge University Press 2013). The first in particular was very widely discussed and provided both a trenchant critique, as well as compelling alternative, to a dominant paradigm in Platonic interpretation. Its enormous impact on Platonic studies made Charles Kahn one of the most important contemporary Platonists, along with the late Gregory Vlastos.

Charles is survived by his wife, sister, four daughters, son, and ten grandchildren.

BNO News recently tweeted this footage from Al Jazeera, along with the description: "At least 3,500 sea lions in Peru have recently died of H5N1 bird flu, nearly 5 times as many as previously reported, the government says." WARNING before you watch: The video is horrific—it's very difficult to watch those poor creatures suffering. — Read the rest