It is currently held, not without certain uneasiness, that 90% of human DNA is ‘junk.’ The renowned Cambridge molecular biologist, Sydney Brenner, makes a helpful distinction between ‘junk’ and ‘garbage.’ Garbage is something used up and worthless which you throw away; junk is something you store for some unspecified future use. (Rabinow, 1992, 7-8)

In the bioscience lab near Tokyo where I did my ethnographic study, the researchers taught me how to do PCR experiments. This was before Covid when almost everyone came to know what PCR was, or at least, what kind of instrumental information it could be good for.[1] The lab was working with mouse models, although I never got to see them in their cages. But the researcher I was shadowing showed me how to put the mouse tail clippings she collected into small tubes. She hated cutting tails, by the way, and preferred to take ear punches when she could. She told me that she didn’t like the way the mice wiggled under her hand, as if they just knew. But at this point anyway, the mice are alive in the animal room and she is only putting small, but vital, pieces of them into a tube to dissolve them down (mice becoming means), to get to the foundation of what she really wants.

I’ve still got the protocol that I typed up from the notes I made with her in the lab. Step 1 was: “Add 75 ul of NaOH to each ear punch tube (changing tips as I go).” The changing pipette tips part was really important to avoid haphazardly spreading around DNA, I learned. I also had to make sure the clippings were at the bottom of the tube and submerged. She said I could flick the tubes with my finger to get the “material” to fall down to the bottom and she showed me how to do it. I also, she cautioned, always had to be very careful of bubbles, but more flicking could help there and by making sure I didn’t put the pipette too far down into the solution. Then we would spin the tubes in the vortex (which I always typed as VORTEX for some reason), add some other reagents, and put it all in the “PCR machine,” but that is not at all its technical name.[2] Then we would usually go with all the others to the cafeteria for lunch.

In writing this now, I couldn’t remember what “NaOH” stood for so I had to ask the internet. And as I looked back over this protocol, and these practices I was just barely learning to embody before the pandemic sent us all home, I realize that they must have settled back in my mind somewhere, just as the material-ness of the lab which anchored them for me has receded like a shrinking lake in a drought summer. But what I do hold on to is what the researcher taught me about the importance of repetition and focus, for a kind of purity of practice, and the diligence to make materials—whether of mice or of sodium hydroxide—do what they ought to do.

Because what captivated me about these initial PCR steps was what appeared to me to be the profound transformation they wrought (of course, I am not the first person to say so)—from fleshy ear punch to silt DNA multiplied in a clear plastic tube, with just a little bit of chemicals and some repetitive cycles of heat—but even more, how this transmutation had the potential to fail in one way, or for one reason, or another. How difficult it could actually be to get the materials, and even the researchers themselves, to do what they ought. Once, I used some unknown solution instead of water because it was on a shelf in an unmarked bottle close to where the water, which I later supposed had gone missing, was usually kept. Once, I didn’t remember to change pipette tips. Or the sense in my hands of precisely what to do next and properly would simply begin to unravel. When we had to throw the tubes in the trash, the researcher comforted me by telling me about a time when her mind wandered for just an instant while pipetting and she lost track of which tube she had last filled with reagent. A minor momentary mistake that grows, and can even burst, into a huge error in the downstream. She taught me that sometimes, if I lifted the tubes to the light to examine their volume of liquid, I might be able to get back on track.[3] Other times the PCR machine might not cycle its heat properly. One machine was already considered to be of questionable working order but the lab didn’t have the funding to replace it. We didn’t know about its full potential for failure until we got all the way through to the very last stage of the process and discovered we had to go back to the beginning with new clippings.

The researcher and I classified these particular (wait, was that water?) experiments-in-the-making as failures because they missed the mark of their intentions. Their purposefulness, decided in advance by the goal of genotyping these mice, was also appended to other purposes, specifically to cultivate a living gene population that the researchers needed for other more central concerns. Trashing the experiments that deviated from this intentionality, although it could be costly, was a seemingly simple decision. After the PCR melt and the second half of the experiment, the electrophoresis machine either “read” back the base pair numbers we were looking for, or those numbers were just wrong and we’d made an obvious mistake. Or worse, everything collapsed into inconclusiveness and we needed to repeat the experiment anyway.[4] In this case, deviation from expectation, and therefore from usefulness, was what pushed experiments to a kind of failure, beyond which point they could not, in this context at least, be so easily reclaimed.

But what does something like “junk” have to do with mice ear punches, chemical transmutation, and mundane laboratory failures? Garbage experiments are routine in scientific practice after all. But as any scientist might tell you, failure can be its own kind of productive; in the least, as a way to learn the value of steady hands, and how to recognize water by smell, or its necessity as a control in genotyping—to become a “capable doer,” as one scientist told me. But beyond these mundane errors, some scientists argue that failures of a particular kind can break open old ways of thinking and doing, although what that failure is, and can be, is variously classified:

Science fails. This is especially true when tackling new problems. Science is not infallible. Research activity is a desire to go outside of existing worldviews, to destroy known concepts, and to create new concepts in uncharted territories. (Iwata, 2020)

I wish “failure” were the trick to seeing and moving beyond the limits of current knowledge. Is that what Kuhn said? I think that paradigm change requires making a reproducible observation that does not fit within the existing model, then going back to the whiteboard. But I don’t think these observations are very well classified as a failure. If failure = unexpected result of a successful experiment/measurement, then I can agree. (Personal communication with laboratory supervisor, 2020)

Failure has more potential than we might often recognize, where an instinct to trash can instead push to new beginnings. Just as Rabinow described Brenner’s description (1992), failure is like junk, those materials or states that are in-the-waiting—waiting to be actualized, reordered, and reclaimed as meaningful, valid and valuable, even if we don’t yet know how or why. Junk is, in this way, more than matter “out of place,” although it may land there interstitially. If “[d]irt is the by-product of a systematic ordering and classification of matter, in so far as ordering involves rejecting inappropriate elements” (Mary Douglas, 1966, 36), then junk is garbage and failure and decay, and even breakdown, on the precipice of being made anew. After all, without intentionality or purposefulness and other values, there can be no garbage, or failed and failing experiments and paradigms, in the first place.

Consider an example that seems categorically different from scientific experiments: inventory management in role-playing videogames. In Diablo 4 (2023), any item picked up from downed enemies or collected in the environment can be marked as “junk” and then salvaged by visiting an in-game merchant. These bits of amour and other gear reappear in your inventory afterwards as junk’s constitute materials, useful again for crafting and building up new things—strips of leather and other scraps as well as blueprints for better stuff. In Fallout 4 (2015), the “Junk Jet” gun lets you repurpose your inventory instead as ammo, anything from wrenches to teddy bears, which can be shot back out into the world and at random adversaries, where you might later be able to pick them up again, if you want. Managing encumbrance in Skyrim (2011), on the other hand, is a task of drudgery and tedium. Almost every item in the game world is moveable, each with its own weight calculation, and can be picked up and stored even accidentally, until your character is weighed down to the point of being unmovable. But the game is designed to make you feel that there is always the possibility that some magical potion, random apple, or 12 candlesticks, might just come in handy for a future encounter, a book that you might really read later, leading to a hesitancy to trash anything. In turn, every item brims with, as yet undiscovered, use-value. As Caitlin DeSlivey argues: “Objects generate social effects not just in their preservation and persistence, but in their destruction and disposal” (2006, 324). And certainly this is true when, over-encumbered deep inside a dungeon, I agonize over which items to drop, in order to move again, in order to continue to collect more—or laugh as I spray the world with cigarettes and telephones.

A decaying dog, reanimated by something that is not supposed to be there. (Image by Sarah Thanner, used with permission)

For me then, junk is a way to look for when and where particular boundaries of the useful or valuable—and even the clean and functioning—are “breached” (Helmreich 2015, 187), and then reordered. Although Helmreich is speaking to scientific experimental practices and their organizing ideologies, his insight is useful for junk’s attention to those very breaches: “moments when abstractions and formalisms break, forcing reimaginations of the phenomena they would apprehend” (185). Of course, junk DNA itself has experienced this very kind of breaching—more recent scientific research demonstrating its non-coding role is actually not without usefulness (c.f. Goodier 2016)—(re)animating it for future use. And although DeSilvey is describing vibrant multispecies-animated decay within abandoned homesteads, like Helmreich, she points to junk’s transformative potential. We just have to dig through rotted wood and insect-eaten paper, or virtual backpacks and books, to find it.

Junk merges failure, trash, and decay with the processual and everyday negotiation of culturally meaningful and policed categories: garbage, scraps and waste, but also “breakdown, dissolution, and change” (Jackson 2014, 225). Although Steven J. Jackson describes the ways these last three are fundamental features of modern media and technology, an anthropology of junk collects and extends these processes into broader techniques and social practices. Junk can help us see connections criss-crossing symbolic and material breakage and disintegration. It helps us see in/visibility of the dirty and diseased, not as a property of any material or technological object alone, but as also always in coordination and collaboration with the ways they are imagined and invested—and more, always enmeshed in variously articulated forms of power.

If infrastructures like computer networks, for example, become (more) visible when broken (Star 1999), it is not their brokenness or decay in an absolute sense that reveals them, but the way their state change defies our everyday and embodied expectations—the way they push against normativity. We may be just as surprised to find things in good working order.

Metal becoming wood in “animation of other processes” (DeSilvey 2006, 324). (Image by Sarah Thanner, used with permission)

Bit rot after all, has just as much to do with the made-intentionally-inoperable systems that force the decay, or really uselessness, of data (Hayes 1998), as it does with any actual mold on CD-ROMS and other corruptions of age and wear. In fact, digital information or technological and material infrastructures don’t become broken, just as they don’t become fully ever fixed either. Breaks and breaches are hardly so linear. Instead, these are “relative, continually shifting states” (Larkin 2008: 236). This view may be in contrast to Pink et al.’s suggestion to attend “to the mundane work that precedes data breakages or follows them” (2018, 3), but not to their entreaty to follow those everyday practices of maintenance and repair, and even intentional failure and forced rot. This is not simply because data and other material practices like PCR experiments may fail under given conditions or focused intentions, perhaps as a result of a momentary distraction or a faulty machine—or in the case of programming, because debugging is actually 90% of the work, as one bioinformatician told me. Indeed, software testing in practice goes beyond merely verifying functionality or fixing bugs and broken bits of code, but helps to define and make “lively” (Lupton 2016) what that software is, and can do, and can be made to do in the first place (Carlson et al. 2023). Along the way, as a generative process, testing, tinkering, and fixing have social effects (DeSilvey 2006) which are external to, but always in extension of, broken/working materials themselves (Marres and Stark 2020).

More importantly, perhaps, broken things can be used, as Brian Larkin argued in relation to Nigerian media and infrastructures, as a “conduit” to mount critiques of the social order (2008, 239)—to call attention to inconsistency and inequality, and to demand or remodulate for change. To see this resistance at work demands a collating of junk practices. As Juris Milestone wrote in his description of a 2014 American Anthropology Association panel, “What will an anthropology of maintenance and repair look like?”:

Fixing things can be both innovation and a response to the ravages of globalization—either through reuse as a counter-narrative to disposability, or resistance to the fetish of the new, or as a search for connection to a material mechanical world that is increasingly automated and remote.

Junk’s transformative potential asks us to see removal and erasure, or in Douglas’ terms “rejection,” as always coupled to these reciprocal practices: rebirth, repair, repurpose, renewal. In this way, junk shows us the way decay, even technological corruption, is less a “death” than a “continued animation of other processes” (2006, 324).

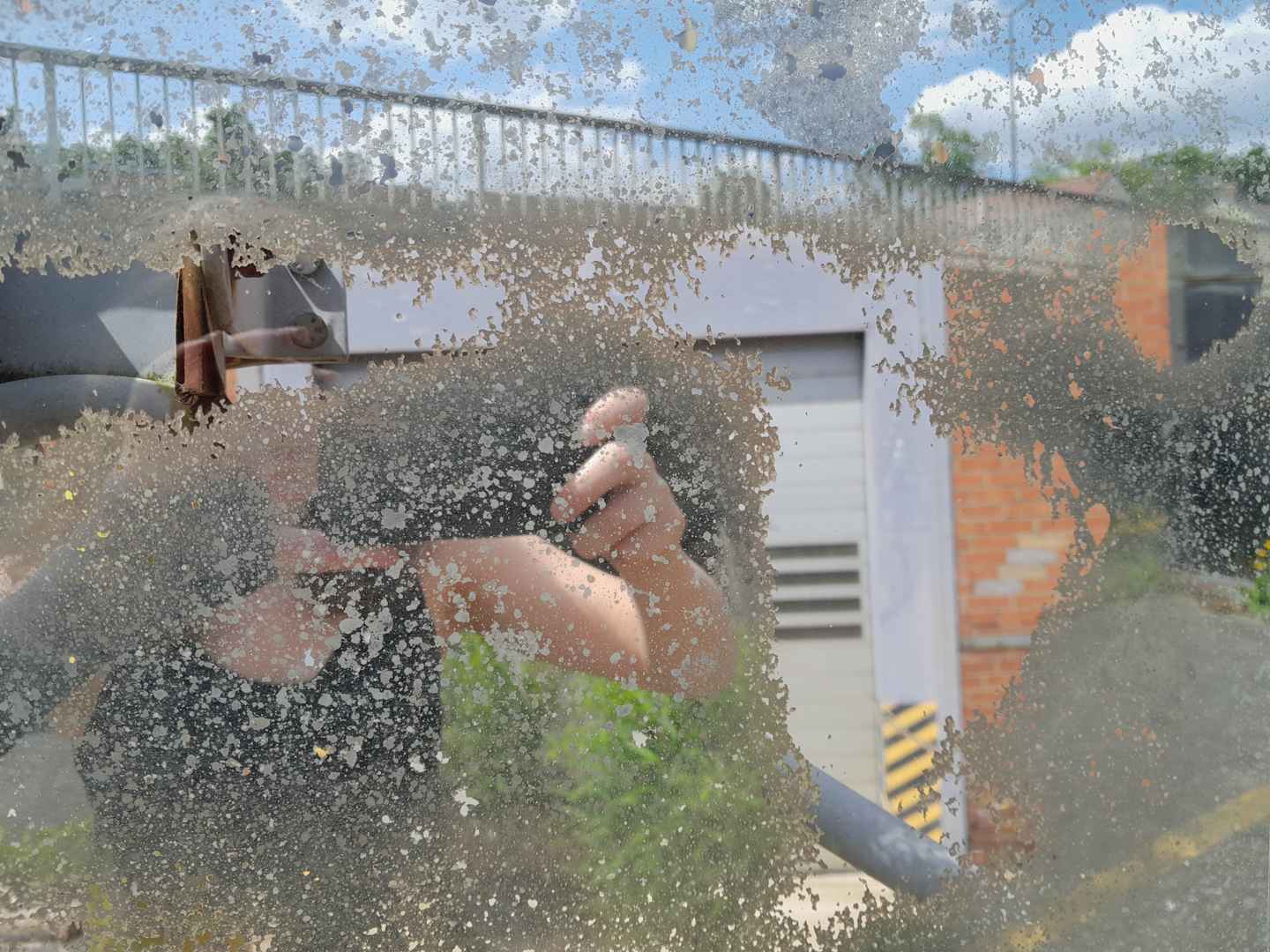

But if junk describes a socio-cultural ordering system concerned with practices of moving materials—even ideas and people—into and out of categories of value and purposefulness, it must also contend with the vital agency of other material and microscopic worlds, which just as easily unravel out or spool up regardless of human presence, intention, and desire. Laboratory mice in fact are particularly disobedient, they hardly ever behave as they are supposed to—just as cell cultures in a lab are finicky and fail to grow to expectations, and junk ammo from the Junk Jet has a 10% chance of becoming suspended in mid-air, becoming irretrievable.[6] If we repurpose sites or moments of breakdown to resist configurations of power, then materials themselves are also always resisting what they ought to do or become.[7] This is the draw of the things in which we are enmeshed, where we are always extending, observing, destroying and deleting. If junk is the possibility, under particular cultural expectations and desires, for things to be pushed or cycled across such thresholds, and also, of making and unmaking these, it also must contend with the things themselves—with what we see in a corroded mirror, looking, or not, back at us.

A woman in a corroded mirror, disappearing and extending. (Image by Sarah Thanner, used with permission)

Although junk may be over-bursting in its use here as a metaphor, I argue it can still usefully be used to stitch growing anthropological attention to material decay, breakage, and deviation together with tinkering, maintenance, and repair—across locations, states, practices and materialities. Granted, “manifesto” is also a too decisive word to attach to this short piece. Too sure of itself. But this post is also an attempt to challenge the understanding of what it means to be (academically) polished and complete. I use manifesto here mostly tongue-in-cheek, while still holding to the idea that any argument has to begin in small seeds, and start growing from somewhere.

My thinking about junk began years ago with Brian Larkin’s attention to breakdown (2008). More recently, I found DeSilvey (2006) by way of Pink et al. (2018); and Jackson (2014) from Sachs (2020); and Hayes (1998) from Seaver (2023). This lineage is important because I am not inventing, but building. These ideas are also bits and tears of conversations with Libuše Hannah Vepřek, Sarah Thanner and Emil Rieger, and very long ago, Juris Milestone. But everything gets filtered first through Jonathan Corliss.

This research has been supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science’s Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 20K01188.

[1] PCR stands for polymerase chain reaction. It is an experimental method for duplicating selected genetic material in order to make it easier to detect in secondary experiments.

[2] Thermal cycler, for anyone interested. Also, just to note, but for the purposes of this retelling, I gloss over the most detailed part in writing so simply: “add some other reagents” and later, “after the PCR ‘melt’ and the second half of the experiment.”

[3] I wrote in my protocol notes, as an (anthropological) aside to myself: “K. stressed that the amount of liquid in this case doesn’t have to be super accurate, but that this is rare in science experiments. When I tried it for the first time, I almost knocked over all the new tips and also the NaOH solution which can cause burns! Yikes~)”

[4] Inconclusiveness includes an unclear or unaccounted for band in the electrophoresis gel, which is seen in the machine’s output as an image file.

[5] The images in this post are part of the artistic work of Sarah Thanner, a multimedia artist and anthropologist who playfully and experimentally engages with trashing and untrashing in her work.

[6] Fallout Wiki, Junk Jet (Fallout 4), https://fallout.fandom.com/wiki/Junk_Jet_(Fallout_4)

[7] Here, I also gloss over (new) materiality studies, Actor Network Theory, etc. which have linages too long to get to properly in this small piece.

Carlson, Rebecca, Gupper, Tamara, Klein, Anja, Ojala, Mace, Thanner, Sarah and Libuše Hannah Vepřek. 2023. “Testing to Circulate: Addressing the Epistemic Gaps of Software Testing.” STS-hub.de 2023: Circulations, Aachen Germany, March 2023.

DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2006. “Observed Decay: Telling Stories with Mutable Things.” Journal of Material Culture 11: 318-338.

Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge.

Goodier, John L. “Restricting Retrotransposons: A Review.” Mobile DNA 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-016-0070-z

Hayes, Brain. 1998. “Bit Rot.” American Scientist 86(5): 410–415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1511/1998.5.410.

Helmreich, Stefan. 2015. Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Iwata, Kentaro. 2020. “Infectious Diseases Do Not Exist.”「感染症は実在しない」あとがき. Retrived May 9, 2020, https://georgebest1969.typepad.jp/blog/2020/03/感染症は実在しないあとがき.html.

Jackson, Steven. J. 2014. “Rethinking Repair.” In T. Gillespie, P. J. Boczkowski, & K. A. Foot (Eds.), Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society. Cambridge: MIT Press. Pp. 221-239.

Lupton, D. 2016. The Quantified Self: A Sociology of Self Tracking. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Marres, N, Stark, D. 2020 “Put to the Test: For a New Sociology of Testing.” British Journal of Sociology 71: 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12746.

Milestone, Juris. 2014. “What Will an Anthropology of Maintenance and Repair Look Like?” American Anthropological Association Meeting.

Pink, Sarah, Ruckenstein, Minna, Willim, Robert and Melisa Duque. 2018. “Broken Data: Conceptualising Data in an Emerging World.” Big Data & Society January–June: 1–13. https:// doi:10.1177/2053951717753228.

Rabinow, Paul. 1992. “Studies in the Anthropology of Reason.” Anthropology Today 8(5): 7-8.

Sachs, S. E. 2020. “The Algorithm at Work? Explanation and Repair in the Enactment of Similarity in Art Data.” Information, Communication & Society 23(11): 1689-1705. https://doi:10.1080/1369118X.2019.1612933.

Seaver, Nick. 2022. Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Star, Susan Leigh. 1999. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43(3): 377–391. https://doi:10.1177/ 00027649921955326.

The video below this text is interactive.[1] To view, click play and follow the instructions you see on the screen. As you watch, look for areas that you can click with a mouse (or tap with your finger, if on a mobile device)[2] or see what appears when you mouse over different areas of the image at different times. What do you see?[3]

[1] This multimodal content, due to technological limitations, may not be accessible to all. If the multimodal experience is not accessible to you, please visit the text based version for visual and audio descriptions and full-text transcription or listen to the audio narration:

Audio Narration by Kara White

[2] On mobile devices, we suggest viewing the page in landscape mode and selecting “Distraction Free Reading” in the top-right corner.

[3] This is an interactive video. This video is designed to get the viewer or reader to “search” the image for interactive buttons. To navigate by keyboard, you can use the tab key to switch between objects. Press enter to click on each object. The text is revealed by interacting with objects that appear at various times during the video. As each object appears, the video will pause, and you will be instructed to click or press enter for the text to appear. When you’re ready to continue, click the play button object or press enter.

Ballestero, Andrea, and Brit Ross Winthereik, eds. 2021. Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis. Experimental Futures: Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ingold, Tim. 2018. Anthropology: Why It Matters. Medford: Polity Press.

Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. International Library of Sociology. London ; New York: Routledge.

This is a work of hypertext-ethnography.

It is based on my research of a small genetics laboratory in Tokyo, Japan where I am studying the impact of the transnational circulation of scientific materials and practices (including programming) on the production of knowledge. In this piece, I draw primarily from my participant observation field notes along with interviews. I also incorporate other, maybe more atypical, materials such as research papers (mine and others), websites and email.

The timeframe for this work is primarily the spring of 2020 and the setting is largely Zoom. Although I began my research in 2019 physically visiting the lab every week, in April 2020, it—and most of the institute where the lab is located—sent researchers home for seven weeks. That included me. Luckily, the lab quickly resumed its regular weekly meetings online (between the Principal Investigator (PI) and individual post-docs for example, as well as other group planning and educational meetings), and I was invited to join. I continued my ethnography for an additional year in this style.

Working in Zoom, my field notes narrowed to transcript recording, and I eventually grew frustrated with the loss of texture and diversity of information, even hands-on, that I had encountered being in-person, in the lab. However, a good deal of my original field notes from the lab describe scientists working silently and independently at their laptops, and on what kinds of materials or with what tools I could hardly, at the time, fathom. Online meetings allowed me to join scientists, inside their computers in a way, where I had a more intimate access to their experimental work.

At the same time, the lab was undergoing a transition. Scientists who practiced “wet” experiments (involving human/animal materials in chemical reactions), like many others, were mostly at home and shifting to planning or learning new skills. But even before the pandemic, this laboratory was gradually incorporating more and more “dry” techniques—using computational methods as part of their genetic research. This includes programming languages like Python and R (note that R appears in this work as a literary device more than accurate depiction), and more accessible entry points such as “no-code” and other web-based tools for analysis that require less time-consuming training. More of the researchers began to learn and play with these methods while at home in that time of “slow down,” and with more or less success. While coding scripts are not so completely different from the experimental protocols that scientists use in the lab (each takes time, patience and a kind of careful attention to perfect), they presented a general challenge that was compounded by being separated at home. In my case, just as I felt I was getting a grasp of the technical terms and biological concepts harnessed in the lab’s research projects, I was exposed to, and lost in, a layer of coding practices with which I had no background knowledge. This time of transition, and of destabilization, is ultimately the location of this work. It weaves two threads: a closing down into relative isolation while at home (and a limiting to the kind of surface data I could collect), and a shared opening up to new practices and forms of lab “work,” including computational research (and for me, remote participant observation). This is the experience that I work to recreate here in interactive form.

As a kind of ethnographic accounting, hypertext-ethnography remains uncommon. Despite the promise of early works such as Jay Ruby’s Oak Park Stories (2005) and Rodrick Coover’s Cultures in Webs (2003), hypertextual forms have been mostly left for other disciplines like documentary filmmaking (some examples are described by Favero, 2014). For most, its bare textual form—as in this piece—might even be considered horribly outdated. For me, hypertext is a method to tell a different kind of story. I use this as a form of ethnographic representation along a relatively rhizomatic path to convey the feeling of being “always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1993, 25). Here, interpretation emerges as part of the direction the reader intentionally, or accidentally, takes through the material; it is therefore open in ways different from traditional academic texts. Any “narrative” emerges primarily in juxtaposition of moments, comments, records and links that also refuses complete(d) analysis. At the same time, hypertext highlights the multivocal and always emergent nature of ethnographic data, destabilizing authorship, if even in small ways. It helps me to raise familiar questions which don’t have (any) easy answers: how do we ever know what we know, and how much do we really need to know and understand to faithfully represent others?

For me, this “story” is only one story among many others which I have yet to fully see.

Coover, R. (2003). Cultures in webs: Working in hypermedia with the documentary image. CITY: Eastgate Systems.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1993) A thousand plateaus. Minnesota: The University of Minnesota Press.

Droney, D. (2014) “Ironies of laboratory work during Ghana’s second age of optimism.” Cultural Anthropology 29:2, 363-384, https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.2.10

DeSilvey, C. (2006) “Observed decay: Telling stories with mutable things.” Journal of Material Culture 11:3, 318–338, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506068808

Favero, P. (2014) “Learning to look beyond the frame: reflections on the changing meaning of images in the age of digital media practices.” Visual Studies 29:2, 166-179, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2014.887269

Larkin, B. (2008) Signal and noise: Media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

Li N., Jin K., Bai Y., Fu H., Liu L. and B. Liu (2020) “Tn5 transposase applied in genomics research.” Int J Mol Sci. Nov 6;21(21):8329. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218329.

Krasmann, S. (2020) “The logic of the surface: on the epistemology of algorithms in times of big data.” Information, Communication & Society, 23:14, 2096-2109, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1726986

McClintock, B. (1973) Letter from Barbara McClintock to maize geneticist Oliver Nelson.

Pink S., Ruckenstein M., Willim R., and M. Duque (2018) “Broken data: Conceptualising data in an emerging world.” Big Data & Society January–June: 1–13.

Ravindran, S. (2012) “Barbara McClintock and the discovery of jumping genes.” PNAS 109 (50) 20198-20199, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219372109

Ruby, J. (2005) Oak Park stories. Watertown: Documentary Educational Resource.

Venables, W. N., Smith D. M. and the R Core Team (2022) An introduction to R. Notes on R: A programming environment for data analysis and graphics, version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31).

Virilio, P. (1997) Open sky. Translated by J. Rose. London: Verso.

Virilio, P. (1999) Politics of the very worst: An interview by Philippe Petit. Edited by S. Lotringer and translated by M. Cavaliere. New York: Semiotext(e).

Virilio, P. (2000) Polar inertia. Translated by P. Camiller. London: Sage

When seen through the experiences and histories of experimentation and care, plants such as roses can bring new insights into the affective and material entanglements of more-than-human relations. My ethnographic encounter with Mr. Changa, a prominent figure in the world of horticulture and plant nurseries in Pakistan, gives us a glimpse on “seeing and being-with” (Haraway 1998) non-human others, such as roses, to foreground the making of social worlds through affect. These encounters show that even though colonial inscriptions on social understandings of nature were marked in influences over tastes and attitudes (Mintz 1985), an attention to nuanced affects, articulations, and values can disrupt the process of creating “authentic” relations with plants and singular legacies of expertise. Writing against the dominance of an object-oriented ontology in mainstream science and technology narratives, this post follows scholarship that emphasizes an “anthropology beyond the human” (Kohn 2013) to center the connections between plants and humans as not only metaphorical but literal (De La Cadena 2010).

One of the varieties Mr. Changa cultivates is the Moonberry Rose that has a distinctive pink shade. While color, scent, texture, petal shapes, and stem features are some of the ways to distinguish the flowers, rose growers will also identify soil conditions, water quality, and climatic conditions as forms of care. Photo by Author.

When I entered the plant nursery, I saw an elderly man fervently engaged in talking to customers and meting out instructions to other assistants. Rows of ornamental trees, house plants, and various seasonal flowers were arranged in an eye-catching manner. The nursery was buzzing with activity. I was surprised to learn that some of the customers had traveled from as far as Karachi, more than seven hundred miles away, to Pattoki. The city is the hub of wholesale trading for plants in Pakistan, as well as home to more than a hundred private nurseries. While Pattoki is known as the “City of Flowers,” the Changa Nursery is famous for the most coveted flower, the rose. As Mr. Changa declared enthusiastically, “Yahan aam, shatoot ki nurseries tau baht thee’ magar mein pehlay din se gulab pe latoo tha (There were plenty of nurseries selling mango trees and Mulberry, but I was enamored by the rose from day one).”

As we sat down next to his personal rose garden to talk about the history of Pattoki and his work with roses, Mr. Changa was no longer holding a pen and sales slips. Instead, he had brought out some of his favorite books to show us the techniques and climatic zones for cultivating different varieties of roses. The first edition of David Austin’s English Rose, a sacred text for any serious rose grower according to Mr. Changa, was a cherished companion among his extensive collection of books. This book documented the journey of British horticulturalist David Austin who set a world standard for rose cultivation when he successfully created the English rose in 1969.[1] Mr. Changa’s admiration for David Austin’s devotion to the craft and care of roses was not a complacency with colonial systems of knowledge but rather the wonder of experimentation joined with care for the roses he was growing. As Archambault (2016) has proposed, affective encounters occur when “a meeting with someone or with something” can produce “some sort of effect; when it inspires, unsettles, troubles, moves, arouses, motivates, and/or impresses” (249). It was in the same state that Mr. Changa went over descriptions in the book. He took me through marked pages in his collection to show the process and types of pavandkari (grafting) and the potential results on the color, texture, and form of the rose plants.

Without any formal education in horticulture or botany, Mr. Changa’s journey on experiencing plants came from his schooling in the village. It was there that he learned of different planting practices and different types of soil such as the bhal mitti (clay soil), halki mitti (light soil), raet mitti (loamy soil), and khaalis raet (pure sand). He grew up as a farmer’s son in the fertile Indus plains and even as he marked a different path as a nursery business owner, he found that his roots in Pattoki could not be disengaged from his passion for roses.

Grafting is a botanical technique to cross-fertilize different varieties of plants. This allows for plants to evolve their apparent physical qualities as well as non-visible characteristics, such as resistance to disease. Grafting experiments have brought about new varieties of plants and extended plant networks all over the world. Photo by Author.

At the same time, Pattoki’s development as the hub of nurseries is entwined with a historical, political, and capitalist construction on the place of nature. The city is situated next to colonial-era railway tracks and postcolonial road infrastructure that expanded the possibilities of intra-country trade and promotion of Mr. Changa’s roses. Pattoki’s ability to physically sustain such a large number of nurseries and plant farms also comes from its proximity to Punjab’s rivers and the fertile Indus plain. Furthermore, the soil that nourished the roses came from riverbeds, mixed with ganay ki mael (sugarcane leftovers) and rice ash, from the adjoining agricultural fields. However, while the urban sprawl raises concerns on the availability of these agricultural residues and soil health, it has spurred the demand and circulation of nursery-grown plants and flowers. The Changa Nursery Farms “Rose Specialist” is one example of businesses that have taken to social media platforms to expand the potential and circulation of their roses and plants. In these transformative mediations, the roses’ beauty comes to be prized through its grower’s reputation and fame.

Of the over two hundred hybrid varieties produced under his care and supervision, Mr. Changa had named several of them after prominent national figures or events. At the rose farm, he took us through several different ones. “This one is ‘Our Allama Iqbal’… this one is August 14… this one is Dr. Iqbal,” Mr Changa explained as he gently cupped the roses by holding them from the bottom center.

The image from Mr. Changa’s nursery shows a news paper article highlighting the work of Changa Nursery Farms juxtaposed to a newspaper page illustrated with the photos of Pakistan’s national icons, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founding father, and Allama Iqbal, the national poet. Photo by Author

Roses are widely acclaimed for their aesthetic appeal as well as their symbolic attribution with joy and love. The desi gulaab, a shocking pink wild rose, is a ubiquitous sight at Pakistani weddings as well as newly covered graves of cherished relatives and friends. Roses are not just visually attractive but an olfactory and gustatory delight for many. In fact, for cosmetic and beauty products, as well as beverage companies, these qualities of scent and taste alone can become the raison d’être for roses in their supply chains. Rose extracts can be sold for a couple thousand to several tens of thousands of Rupees, whereas rose oils are three times more expensive. “Soap companies will count each and every drop that goes into the mixture because the extracts can be more expensive than gold,” Mr. Changa explained. On the other hand, the state’s lack of interest and financial capacity on resourcing and encouraging local expertise has prompted a constant struggle to be seen. Without a patent, his roses and ideas will not travel the world with the same prestige and recognition that accompanied David Austin’s flowers to Pakistan.

Yet, somewhere between/beyond colonial inheritance of commoditizing relations with nonhuman others and neoliberal governance of globalization, Mr. Changa’s and the roses’ affective and material entanglements unsettle singular readings of human-plant relations. Analyzing his multi-decade association with caring for, experimenting with, promoting, and cultivating roses, along with the ecological history and constitution of Pattoki, shows that it is imperative to locate human and more-than-human social worlds through their “collaborative” (Smith 2016) making of the other.

The author would like to thank Mr. Changa and Mr. Najeeb for their assistance with this project.

[1] The English Rose, a hybrid variety of roses, are famous for their fragrance, form, and resistance to diseases.

Archambault, Julie Soleil. 2016. “Taking Love Seriously in Human-plant Relations in Mozambique: Toward an Anthropology of Affective Encounters.” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 2: 244-271.

De la Cadena, Marisol. 2010. “Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections Beyond ‘Politics.’” Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 2: 334–70.

Haraway, Donna J. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. University of California Press.

Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York, NY: Viking, 1985.

Smith, Mick. 2016. “On ‘Being’ Moved by Nature: Geography, Emotion and Environmental Ethics.” In Emotional Geographies, pp. 233-244. Routledge.

"We define ourselves more by certain emotions. I've never heard anybody say, 'I'm trying to get over my embarrassment and I feel so inauthentic.'"

The post “It Is Not How You Feel”: Batja Mesquita on How Different Cultures Experience Emotions appeared first on Public Books.

In the film Doctor Dolittle (1967), the title character yearns to “Talk to the Animals,” as the song goes, to understand their mysterious and often vexing ways. It is interesting to observe a similar impulse to understand and communicate with algorithms, given their current forms of implementation. Recent research shows that intense frustration often emerges from algorithmically driven processes that create hurtful identity characterizations. Our current technological landscape is thus frequently embroiled in “algorithmic dramas” (Zietz 2016), in which algorithms are seen and felt as powerful and influential, but inscrutable. Algorithms, or rather the complex processes that deploy them, are entities that we surely cannot “talk to,” although we might wish to admonish those who create or implement them in everyday life. A key dynamic of the “algorithmic drama” involves yearning to understand just how algorithms work given their impact on people. Yet, accessing the inner workings of algorithms is difficult for numerous reasons (Dourish 2016), including how to talk to, or even about, them.

Common shorthand terms such as “the algorithm” or even “algorithms” are problematic considering that commercial algorithms are usually complex entities. Dourish (2016) notes that algorithms are distinct from software programs that may make use of algorithms to accomplish tasks. The term “algorithm” may also refer to very different types of processes, such as those that incorporate machine learning, and they may be constantly changing. For the purposes of this discussion, the term “algorithm” will be used while keeping these caveats in mind. In this post, I relate the findings of ethnographic research projects incorporated into the new volume, The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology (Costa et al. 2022), in which interviewees use the term to narrativize troubled interactions they experienced with devices and systems that incorporate algorithmic processes.

Simply pinpointing how algorithms work is a limited approach; it may not yield what we hope to find (Seaver 2022). In studying technologists who develop music recommendation algorithms, Nick Seaver (2022) reminds us that algorithms are certainly not the first domain that ethnographers have studied under conditions of “partial knowledge and pervasive semisecrecy” (16). He lists past examples such as magicians, Freemasons, and nuclear scientists. Seaver argues that researching algorithmic development is not really about exposing company secrets but rather more productively aims to reveal “a more generalizable appraisal of cultural understandings that obtain across multiple sites within an industry” (17). A different approach involves exploring algorithms’ entanglements in an “ongoing navigation of relationships” (15). The idea is to reveal the algorithmic “stories that help people deal with contradictions in social life that can never be fully resolved” (Mosco 2005; see also Zietz 2016).

In order for data to “speak” about a domain vis-à-vis a group of users, data must be narrativized (Dourish and Goméz Cruz 2018). In the domain of machine learning, large-scale data sets accumulated from the experiences of many users are subsequently used to train a system to accomplish certain tasks. The system then must translate the processed information back so that the information is applicable to the individual experiences of a single user. Algorithmic data must ultimately be “narrated,” especially for devices that have the potential to “re-narrate users’ identities in ways that they strongly [reject] but [cannot] ignore” (Dourish and Goméz Cruz 2018, 3). Dourish and Goméz Cruz argue that it is only through narrative that data sets can “speak,” thus extending their impact, albeit in ways that may differ significantly from designers’ initial conceptions.

In light of this context, responding to algorithms through ethnographic narrative emerged as an important theme in a volume that I had the pleasure of co-editing with Elisabetta Costa, Nell Haynes, and Jolynna Sinanan. We recently saw the publication of our ambitious collection, The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology (Costa et al. 2022), which contains forty-one chapters covering ethnographic research in twenty-six countries. The volume contains numerous chapters and themes pertaining to science and technology studies, including a section specifically devoted to “Emerging Technologies.” Additional themes include older populations’ struggles with technology, Black media in gaming ecosystems, transgender experiences on social media, and many other relevant themes. The volume also collectively tackles numerous media types including digital spaces, virtual reality, augmented reality, and historical media forms.

One science and technology-related theme that emerged across different sections of the volume involved perceptions of algorithmic usage and impacts on individuals. Several chapters explored identity characterizations that users of technologized devices, such as the Amazon Echo and the Amazon Echo Look, as well as spaces such as the video-sharing platform of YouTube, found violative of their sense of self and well being. In her chapter, “Algorithmic Violence in Everyday Life and the Role of Media Anthropology,” Veronica Barassi (2022) explored the impacts of algorithmic profiling on parents through an analysis of Alexa, the voice-activated virtual assistant in the home hub Amazon Echo. The chapter examines the experiences of families using Alexa in the United Kingdom and the United States during her study from 2016-2019.

Talking back to the algorithm. Image from Pixabay.

Participants in Barassi’s study often felt that the product engaged in demeaning algorithmic profiling of them. For example, a woman named Cara whom Barassi met in West Los Angeles related how angry and irritated she felt because she was automatically targeted and profiled with weight loss ads simply because she was a woman over 50 years old. Feeling belittled by such profiling, she told Barassi, that “there is so much more to me as a person.” Amy, another participant in her study who was actively trying to lose weight, felt that algorithmic profiling concentrated on a person’s vulnerabilities, such that every time she went on Facebook she was bombarded with ads for new diets and plus-size clothing. She too used exactly the same phrase, that there was “so much more to her as a person,” than the algorithmically-generated profiles constructed.

The commentary that Barassi collected from participants represents an attempt to “talk back” to the “algorithm” or perhaps more accurately the developers, companies, and societal perspectives that have collectively implemented violative profiling. By relating their experiences, these narratives work to counteract the feelings of powerlessness that many interviewees felt in the technologized construction and representation of their perceived identity.

Another important aspect of Barassi’s contribution is to broaden analysis of algorithmic creation and impact beyond a particular piece of technology, and understand how algorithmic profiling and predictive systems are deeply intertwined with forms of bureaucracy. She observes that algorithmic profiling engages in symbolic violence because it “pigeon-holes, stereotypes, and detaches people from their sense of humanity” (Barassi 2022, 489). Barassi argues that we must attend far more closely to the relationship between bureaucracy and structural violence as instantiated in algorithmic profiling.

Similar interviewees’ experiences of feeling belittled by algorithms emerged in the chapter by Heather Horst and Sheba Mohammid, entitled “The Algorithmic Silhouette: New Technologies and the Fashionable Body” (2022). Horst and Mohammid studied the Amazon Echo Look, an app that compares outfits and provides fashion recommendations based on expert and algorithmic information. Priced at $199 and released widely in the US market in 2018, it was ostensibly perceived as a democratizing fashion tool, given that the average user would not ordinarily have daily customized access to fashion expertise.

Horst and Mohammid examined use of the device among women in Trinidad in 2019-2020. One of its features was called Style Check, in which the user selected and tried on two different outfits and submitted images of themselves wearing the outfits for the device to compare. It provided a percentage preference ranking, along with a narrative about the recommendation. Women in the study noted that the system could be very useful for providing recommendations and affirming their choices, particularly for meeting their criteria to appear professional in their wardrobe.

Yet some women felt that the device misrecognized them or their goals in oppressively normative ways. In one instance, a woman was threatened to be banned from adding images due to violating “community guidelines” because she was trying to compare herself wearing two bikinis. Another woman complained that the device’s recommendations seemed to be geared to select garments that made her appear slimmer. In an interview she noted:

It’s assuming that you want a slimmer silhouette, less curves, less flare…it doesn’t take into consideration me, like my personal preferences. It’s comparing me basically using its algorithm and how do I know that your algorithm is as inclusive as it should be, you know?

They conclude that these tensions reveal complexities that emerge when devices do not translate across cultural contexts. Their research demonstrates how inherent biases as instantiated in devices and systems reproduce structural inequality. Horst and Mohammid (2022) recommend analyses that can “give feedback to designers and others at particular points in the life of algorithms and automation processes” (527). They recommend taking a “social life of algorithms” approach that considers how algorithmic processes are embedded in cultural and social relations, and how particular values become normative. Feedback from people interacting with algorithmic products needs to be collected and circulated, particularly to challenge the “inevitability” narrative of technical impact that often accompanies the emergence of new technologies.

Zoë Glatt (2022) writes about perceptions of algorithms among YouTube influencers in London and Los Angeles between 2017 and 2021 in her chapter, “Precarity, Discrimination and (In)Visibility: An Ethnography of ‘The Algorithm’ in the YouTuber Influencer Industry.” Drawing on fieldwork among hard-working videographers, video editors, performers, and marketers, Glatt’s chapter traces how people respond to algorithmic recommendations on the YouTube platform, which directly impact influencers’ livelihoods. She found that “algorithmic invisibility,” or having work deprioritized or omitted on recommendation lists based on algorithmic rankings, is a common fear even among successful content creators with sizable followings. One vlogger expressed her deep concerns about platform invisibility:

Over the past year it has all gone to hell. There’s just no pattern to what is happening in essentially my business, and it is scary and it’s frustrating. I don’t know if people see my videos, I don’t know how people see my videos, I don’t know what channels are being promoted, I don’t know why some channels are being promoted more than others. There’s just no answers, and that’s scary to me. (Excerpted from a vlog by Lilly Singh 2017)

Glatt makes the important contribution of analyzing the cultural and economic meanings that creators attach to assumptions about algorithms. In triangulating what creators say about algorithms with how they feel about them, and the actions that influencers take in response, Glatt provides an important framework for parsing algorithmic interactions in culture. Glatt’s findings that influencers found the algorithm to be unpredictable and stressful underscore the importance of researchers to help hold developers and implementers accountable for algorithmic processes, particularly with regard to addressing the algorithmic discrimination that participants reported.

Collectively, these chapters in the Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology include crucial analysis about ethnographic interviewees’ perceptions of algorithms while also providing a mechanism for participants to “talk back” to “algorithms” about how they as individuals are represented in everyday life through technology. Indeed, the stories presented serve as a reminder that it is important to think of algorithms relationally and to provide consistent mechanisms for feedback and implementation strategies to reduce harm. It is indeed time to “talk to the algorithms” by engaging users as well as the designers, processes, and societal organizations that implement them in daily life. We can move on from pinpointing exactly how algorithms work, to shifting attention to establishing ways to meaningfully incorporate feedback to change their impact on human beings around the world.

Barassi, Veronica. 2022. “Algorithmic Violence in Everyday Life and the Role of Media Anthropology.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology. Edited by Elisabetta Costa, Patricia G. Lange, Nell Haynes, and Jolynna Sinanan, 481-491. London: Routledge.

Costa, Elisabetta, Patricia G. Lange, Nell Haynes, and Jolynna Sinanan. 2022. The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology. London: Routledge.

Dourish, Paul. 2016. “Algorithms and their Others: Algorithmic Culture in Context.” Big Data & Society (July – December): 1-11.

Glatt, Zoe. 2022. “Precarity, Discrimination and (In)Visibility: An Ethnography of ‘The Algorithm’ in the YouTube Influencer Industry.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology. Edited by Elisabetta Costa, Patricia G. Lange, Nell Haynes, and Jolynna Sinanan, 544-556. London: Routledge.

Horst, Heather A. and Sheba Mohammid. 2022. “The Algorithmic Silhouette: New Technologies and the Fashionable Body.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Anthropology. Edited by Elisabetta Costa, Patricia G. Lange, Nell Haynes, and Jolynna Sinanan, 519-531. London: Routledge.

Mosco, Vincent. 2005. The Digital Sublime: Myth, Power, and Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Seaver, Nick. 2022. Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ziewitz, Malte. 2016. “Governing Algorithms: Myths, Mess, and Methods.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 41(1): 3-16.