I’m just back from France, where my direct experience of riots and looting was non-existent, although I had walked past a Montpellier branch of Swarkowski the day before it ceased to be. My indirect experience was quite extensive though, since I watched the talking heads on French TV project their instant analysis onto the unfolding anarchy. Naturally, they discovered that all their existing prejudices were entirely confirmed by events. The act that caused the wave of protests and then wider disorder was the police killing of Nahel Merzouk, 17, one of a succession of such acts of police violence against minorites. Another Arab kid from a poor area. French police kill about three times as many people as the British ones do, though Americans can look away now.

One of the things that makes it difficult for me to write blogs these days is the my growing disgust at the professional opinion-writers who churn out thought about topics they barely understand, coupled with the knowledge that the democratization of that practice, about twenty years ago, merely meant there were more people doing the same. And so it is with opinion writers and micro-bloggers about France, a ritual performance of pre-formed clichés and positions, informed by some half-remembered French history and its literary and filmic representations (Les Misérables, La Haine), and, depending on the flavour you want, some some Huntingtonian clashing or some revolting against structural injustice. Francophone and Anglophone commentators alike, trapped in Herderian fantasies about the nation, see these events as a manifestation of essential Frenchness that tells us something about that Frenchness and where it is heading to next. Rarely, we’ll get a take that makes some comparison to BLM and George Floyd.

I even read some (British) commentator opining that what was happening on French estates was “unimaginable” to British people. Well, not to this one, who remembers the wave of riots in 1981 (wikipedia: “there was also rioting in …. High Wycombe”) and, more recently, the riots in 2011 that followed the police shooting of a young black man, Mark Duggan, and where protest against police violence and racism soon spilled over into country-wide burning and looting, all to be followed by a wave of repression and punitive sentencing, directed by (enter stage left) Keir Starmer. You can almost smell the essential Frenchness of it all.

There is much to despair about in these French evenements. Police racism is real and unaddressed, and the situation people, mostly from minorities, on peripheral sink estates, is desperate. Decades of hand-wringing and theorizing, together with a few well-meaning attempts to do something have led nowhere. Both politicians and people need the police (in its varied French forms) to be the heroic front line of the Republican order against the civilizational enemy, and so invest it with power and prestige – particularly after 2015 when there was some genuine police heroism and fortitude during the Paris attacks – but then are shocked when “rogue elements” employ those powers in arbitrary and racist violence. But, no doubt, the possibility of cracking a few black and Arab heads was precisely what motivated many of them to join up in the first place.

On the other side of things, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and La France Insoumise are quite desperate to lay the mantle of Gavroche on teenage rioters excited by the prospect of a violent ruck with the keufs, intoxicated by setting the local Lidl on fire and also keen on that new pair of trainers. (Fun fact: the Les Halles branch of Nike is only yards from the fictional barricade where Hugo had Gavroche die.) There may be something in the riots as inarticulate protest against injustice theory, but the kids themselves were notably ungrateful to people like the LFI deputy Carlos Martens Bilongo whose attempts to ventriloquise their resistance were rewarded with a blow on the head. Meanwhile, over at the Foxisant TV-station C-News, kids looting Apple stores are the vanguard of the Islamist Great Replacement, assisted by the ultragauche. C-News even quote Renaud Camus.

Things seem to be calming down now, notably after a deplorable attack on the home of a French mayor that left his wife with a broken leg after she tried to lead her small children to safety. As a result, the political class have closed ranks in defence of “Republican order” since “democracy itself” is now under threat. I think one of the most tragic aspects of the last few days has been the way in which various protagonists have been completely sincere and utterly inauthentic at the same time. The partisans of “Republican order” and “democracy” perform the rituals of a system whose content has been evacuated, yet they don’t realise this as they drape tricolours across their chests. With political parties gone or reduced to the playthings of a few narcissistic leaders, mass absention in elections, the policy dominance of a super-educated few, and the droits de l’homme at the bottom of the Mediterranean, what we have is a kind of zombie Republicanism. Yet the zombies believe, including that all French people, regardless of religion or race, are true equals in the indivisible republic. At the same time, those cheering on revolt and perhaps some of those actually revolting, sincerly believing in the true Republicanism of their own stand against racism and injustice, even as the kids pay implicit homage to the consumer brands in the Centres Commerciaux. But I don’t want to both-sides this: the actual fighting will die down but there will be war in the Hobbesian sense of a time when the will to contend by violence is sufficiently known, until there is justice for boys like Nahel and until minorities are really given the equality and respect they are falsely promised in France, but also in the UK and the US. Sadly, the immediate prospect is more racism and more punishment as the reaction to injustice is taken as the problem that needs solving.

The forecasted rain held off, the poor air quality caused by Canadian wildfires had abated, and the world’s largest Pride parade stepped off without incident in New York City on the final Sunday in June.

It’s grown quite a bit since the last Sunday of June 1970, when Christopher Street Liberation Day March participants paraded from Sheridan Square to Central Park’s Sheep Meadow.

Seeking to commemorate the one year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, when a police raid touched off a riot at the Greenwich Village gay bar, the event’s planners took inspiration from the organized resistance to the Vietnam War and Annual Reminders, a yearly call for equality from the Philadelphia-based Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations.

Parade co-organizer Craig Rodwell imagined a more freewheeling public event involving larger numbers than Annual Reminders, something that could “encompass the ideas and ideals of the larger struggle in which we are engaged—that of our fundamental human rights.”

In the lead up to the parade, Gay Liberation Front News reported that society stacked the deck against openly gay individuals, an observation echoed by a marcher in lesbian activist Lilli M. Vincenz‘s documentary footage, above:

At first I was very guilty, and then I realized that all the things that are taught you, not only by society but by psychiatrists are just to fit you in a mold and I’ve just rejected the mold. And when I rejected the mold, I was happier.

Look carefully for placards from various participating groups, including the Mattachine Societies of Washington and New York, Lavender Menace, the Gay Activists Alliance, a church, and gay student groups at Rutgers and Yale.

Estimates place the crowd at anywhere from 3,000 to 20,000. In addition to marchers, the parade drew plenty of onlookers, some voicing support like a uniformed soldier stationed at Fort Dix who says “Great, man, do your thing!”. Others came prepared to voice their vigorous opposition.

“He’s a closet queen and you can find him in Howard Johnson’s any night,” a marcher cracks when asked his opinion of a counter demonstrator brandishing a sign invoking Sodom and Gomorrah.

Presumably the second part of this marcher’s comment was not intended to signify that the gent in question had a powerful attraction to the venerable Times Square diner’s fried clams, but rather its upstairs neighbor, the all-male Gaiety strip club.

Compared to the flashy festive costumes and booming club music that have become a staple of this millennia’s Pride Marches, 1970’s proceedings were a comparatively modest affair. Marchers chanted in unison, processing uptown in street clothes – hippie-style duds of the period with a couple of square suits and fedoras in the mix.

A clean cut young man in a windbreaker and natty star-spangled tie expressed frank disappointment that Mayor John Lindsay and other political figures had kept their distance.

Younger readers may be taken aback to hear Vincenz asking him how long he had been gay, but gratified when he responds, “I was born homosexual, it’s beautiful.”

By the time the marchers reached the Sheep Meadow, a number of men had shed their shirts. The parade morphed into a pastoral celebration in which revelers can be seen playing Ring Around the Rosie, plucking weeds to decorate each other’s hair, and attempting to break the record for longest kiss.

A man whose bib overalls have been customized with iron-on letters arranged to spell out Stud Farm expresses regret that he spent so many years in the closet.

Co-organizer Foster Gunnison Jr.’s wish was for every queer participant to leave the parade with “a new feeling of pride and self-confidence … to raise the consciences of participating homosexuals-to develop courage, and feelings of dignity and self-worth.”

That first parade’s marshal, Mark Segal, cofounder of Gay Liberation Front, summed it up on the 50th anniversary of the original event:

The march was a reflection of us: out, loud and proud.

Enjoy a glimpse of 2023’s New York City Pride March here.

Via Kottke

Related Content

The Untold Story of Disco and Its Black, Latino & LGBTQ Roots

Different From the Others (1919): The First Gay Rights Movie Ever … Later Destroyed by the Nazis

Sigmund Freud Writes to Concerned Mother: “Homosexuality is Nothing to Be Ashamed Of” (1935)

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Even though it's often employed innocently, there's an inherent element of tragedy in the phrase "ahead of their time" when it's associated with unsung or overlooked geniuses in a field. If one is "ahead of their time," odds are they'll never live to see the impact their existence inspired or receive the adulation they so richly deserve. — Read the rest

This extraordinary profile of Clarence and Ginni Thomas—he a Supreme Court justice, she among other things an avid supporter of the January 6 insurrection—is a masterclass in everything from mustering archival material to writing the hell out of a story:

There is a certain rapport that cannot be manufactured. “They go on morning runs,” reports a 1991 piece in the Washington Post. “They take after-dinner walks. Neighbors say you can see them in the evening talking, walking up the hill. Hand in hand.” Thirty years later, Virginia Thomas, pining for the overthrow of the federal government in texts to the president’s chief of staff, refers, heartwarmingly, to Clarence Thomas as “my best friend.” (“That’s what I call him, and he is my best friend,” she later told the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.) In the cramped corridors of a roving RV, they summer together. They take, together, lavish trips funded by an activist billionaire and fail, together, to report the gift. Bonnie and Clyde were performing intimacy; every line crossed was its own profession of love. Refusing to recuse oneself and then objecting, alone among nine justices, to the revelation of potentially incriminating documents regarding a coup in which a spouse is implicated is many things, and one of those things is romantic.

“Every year it gets better,” Ginni told a gathering of Turning Point USA–oriented youths in 2016. “He put me on a pedestal in a way I didn’t know was possible.” Clarence had recently gifted her a Pandora charm bracelet. “It has like everything I love,” she said, “all these love things and knots and ropes and things about our faith and things about our home and things about the country. But my favorite is there’s a little pixie, like I’m kind of a pixie to him, kind of a troublemaker.”

A pixie. A troublemaker. It is impossible, once you fully imagine this bracelet bestowed upon the former Virginia Lamp on the 28th anniversary of her marriage to Clarence Thomas, this pixie-and-presumably-American-flag-bedecked trinket, to see it as anything but crucial to understanding the current chaotic state of the American project. Here is a piece of jewelry in which symbols for love and battle are literally intertwined. Here is a story about the way legitimate racial grievance and determined white ignorance can reinforce one another, tending toward an extremism capable, in this case, of discrediting an entire branch of government. No one can unlock the mysteries of the human heart, but the external record is clear: Clarence and Ginni Thomas have, for decades, sustained the happiest marriage in the American Republic, gleeful in the face of condemnation, thrilling to the revelry of wanton corruption, untroubled by the burdens of biological children or adherence to legal statute. Here is how they do it.

Is it ever possible to reconcile clashing visions of national memory?

The post Socialist Nostalgia, Cuban State Power appeared first on Public Books.

The earliest known works of Japanese art date from the Jōmon period, which lasted from 10,500 to 300 BC. In fact, the period’s very name comes from the patterns its potters created by pressing twisted cords into clay, resulting in a predecessor of the “wave patterns” that have been much used since. In the Heian period, which began in 794, a new aristocratic class arose, and with it a new form of art: Yamato-e, an elegant painting style dedicated to the depiction of Japanese landscapes, poetry, history, and mythology, usually on folding screens or scrolls (the best known of which illustrates The Tale of Genji, known as the first novel ever written).

This is the beginning of the story of Japanese art as told in the half-hour-long Behind the Masterpiece video above. It continues in 1185 with the Kamakura period, whose brewing sociopolitical turmoil intensified in the subsequent Nanbokucho period, which began in 1333. As life in Japan became more chaotic, Buddhism gained popularity, and along with that Indian religion spread a shift in preferences toward more vital, realistic art, including celebrations of rigorous samurai virtues and depictions of Buddhas. In this time arose the form of sumi-e, literally “ink picture,” whose tranquil monochromatic minimalism stands in the minds of many still today for Japanese art itself.

Japan’s long history of fractiousness came to an end in 1568, when the feudal lord Oda Nobunaga made decisive moves that would result in the unification of the country. This began the Azuchi-Momoyama period, named for the castles occupied by Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The castle walls were lavishly decorated with large-scale paintings that would define the Kanō school. Traditional Japan itself came to an end in the long, and military-governed Edo period, which lasted from 1615 to 1868. The stability and prosperity of that era gave rise to the best-known of all classical Japanese art forms: kabuki theatre, haiku poetry, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

With their large market of merchant-class buyers, ukiyo-e artists had to be prolific. Many of their works survive still today, the most recognizable being those of masters like Utamaro, Hokusai, and Hiroshige. Here on Open Culture, we’ve previously featured Hokusai’s series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji as well as its famous installment The Great Wave Off Kanagawa. As Japan opened up to the west from the middle of the nineteenth century, the various styles of ukiyo-e became prime ingredients of the Japonisme trend, which extended the influence of Japanese art to the work of major Western artists like Degas, Manet, Monet, van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 opened the long-isolated Japan to world trade, re-established imperial rule, and also, for historical purposes, marked the country’s entry into modernity. This inspired an explosion of new artistic techniques and movements including Yōga, whose participants rendered Japanese subject matter with European techniques and materials. Born early in the Shōwa era but still active in her nineties, Yayoi Kusama now stands (and in Paris, at enormous scale in statue form) as the most prominent Japanese artist in the world. The rich psychedelia of her work belongs obviously to no single culture or tradition — but then again, could an artist of any other country have come up with it?

Related content:

Download 215,000 Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters Spanning the Tradition’s 350-Year History

How to Paint Like Yayoi Kusama, the Avant-Garde Japanese Artist

The Entire History of Japan in 9 Quirky Minutes

The History of Western Art in 23 Minutes: From the Prehistoric to the Contemporary

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Archaeologists digging in Pompeii have unearthed a fresco containing what may be a “distant ancestor” of the modern pizza. The fresco features a platter with wine, fruit, and a piece of flat focaccia. According to Pompeii archaeologists, the focaccia doesn’t have tomatoes and mozzarella on top. Rather, it seemingly sports “pomegranate,” spices, perhaps a type of pesto, and “possibly condiments”–which is just a short hop, skip and a jump away to pizza.

Found in the atrium of a house connected to a bakery, the finely-detailed fresco grew out of a Greek tradition (called xenia) where gifts of hospitality, including food, are offered to visitors. Naturally, the fresco was entombed (and preserved) for centuries by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, Venmo (@openculture) and Crypto. Thanks!

Related Content

Explore the Roman Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, the Oldest Known Cookbook in Existence

How to Bake Ancient Roman Bread from 79 AD: A Video Introduction

Watch the Destruction of Pompeii by Mount Vesuvius, Re-Created with Computer Animation (79 AD)

America’s museums are at a crossroads. Will they be sites of civic education, centered on Americans’ shared history and principles? Or rallying points of advocacy, aiming to replace those principles with divisive identity politics?

Museums aren’t the only institutions facing such challenges. Our ultimate trajectory as a nation will be shaped by the outcomes of a multitude of disputes. Those skeptical of some of America’s principles have gained influence in government and in higher and lower education, the military, the family, and throughout our civic associations. But museums and historic sites deserve special attention right now: they have not been overrun yet, which presents us with both an opportunity and an urgent need.

How we preserve and tell the American story at sites like Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, and Colonial Williamsburg will help decide whether Americans will remain a self-governing people, since forming such a people is one of the main purposes of museums. Civic education promotes responsibility and gratitude, while advocacy that rejects the ideas of the American Founding tends to encourage a revolutionary impulse and feelings of resentment for past errors. Museums can provide occasions to unite around our inheritance and republican principles. Considering the importance of America’s history reminds and prompts us to assume our obligation to ensure America’s perpetuation.

How we preserve and tell the American story at sites like Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, and Colonial Williamsburg will help decide whether Americans will remain a self-governing people, since forming such a people is one of the main purposes of museums.

The State of Affairs

George Washington’s Mount Vernon (run by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association) is an excellent example of how a museum can function as a site for civic education. When visitors go through the mansion, an entire museum, and education center detailing Washington’s accomplishments, they leave with an appreciation for the remarkable character of America’s general. The interactive exhibits put young people in Washington’s shoes, which invites them to be deliberative citizens who consider political questions and reach their own conclusions. Mount Vernon tells the American story fairly and objectively, rightly incorporating the chapter on slavery, while giving Washington his due and strictly adhering to historical standards.

James Madison’s Montpelier (operated by The Montpelier Foundation), on the other hand, discourages civic deliberation by pushing a political narrative on visitors. The site omits pertinent facts and, in crucial instances, Madison’s own words. Some exhibits sweepingly condemn the Founders and Madison for having owned slaves, without adequately addressing their myriad contributions to our nation. While Madison is discussed during a portion of the house tour and through a brief video in the visitor’s center, no exhibits cover the deeds of the man commonly referred to as the Father of the Constitution, and of the Bill of Rights, which Madison introduced in the first federal Congress. The sole exhibit on the Constitution paints it as pro-slavery. The one for children is a dispiriting display on race and slavery, housing a book that prompts children to imagine themselves as aggressors, whipping someone until he is bloodied.

Mount Vernon tells the American story fairly and objectively, rightly incorporating the chapter on slavery, while giving Washington his due and strictly adhering to historical standards.

Monticello and Colonial Williamsburg are mixed bags. Monticello lacks exhibits focused on Thomas Jefferson’s political accomplishments; he was president, vice president, secretary of state, governor, drafter of the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute on Religious Freedom, and founder of the University of Virginia. Most discouraging is the absence of a proper examination of the Declaration of Independence, America’s “rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression,” as Lincoln put it. In turn, Colonial Williamsburg is losing its own story: what the American Revolutionaries did there and what makes the town unique. But, even though these sites omit crucial historical details about the founding, they still offer some good content and are not beyond saving.

Montpelier, the National Trust for Historic Preservation (the organization that owns Montpelier and 26 other sites), and Monticello are all seeking new leadership. Who is selected will tell us much, and determine much, about their trajectory and that of the museum industry.

Republican Aims

Mount Vernon and Montpelier represent fundamental disagreements over the purpose of education and the character of our nation. Civic education centered on republican principles promotes unity, deliberation, responsibility, and gratitude. But far-left ideology requires advocacy, as it asserts that society is composed of power structures in need of dismantling. Reframing history is one step that activists take in pursuing a false sense of equity and justice.

This push for historical reeducation is reflected in the language used by national museum associations. For example, the American Alliance of Museums, which boasts 35,000 members (individuals and organizations), contends that teaching history is not sufficient. Instead, museums should “champion an anti-racist movement” to create a “more just and equitable world.” James French, who maneuvered to become chairman of the Montpelier board last year (and has since left the post while still serving on the board), has also commented that “museums such as Montpelier are dominated by people who look like Madison.” French believes that this must change, and that “[t]he change in the power structure then allows us to affect how public history is presented. And public history is really important.”

French is correct about one thing: public history is really important. Civic education doesn’t just happen in the classroom or cease upon graduation from high school. Museums and historic sites are unique places where multiple generations of Americans, who went to different schools and grew up in various parts of the country, can come together to rediscover their commonalities, the principles and history that formed the American character. Presidential homes, aside from being museums that house relics, can offer our children the reflective and reverential experience of standing in the same room where Abraham Lincoln considered the Emancipation Proclamation or James Madison envisioned the structure and potential of the Constitution.

Museums assume, both for the country and the individual, a special trust of preservation and civic encouragement. That encouragement need not involve glossing over the failings of our past. We distort our history both when we whitewash it and when we overemphasize our shortcomings. Whitewashing is its own kind of propaganda, discouraging deliberation—and so it is inconsistent with the civic virtues needed to sustain a free society. But solely focusing on flaws demoralizes our children, forming them into citizens deprived of the gratitude for and proper pride in accomplishment.

The false promises of victimhood and resentment have never made anyone gracious, honorable, or happy. We want our children to navigate this world with spirited strength and the resolve of being able to contribute to a purpose greater than themselves: to an experiment that depends on their character.

That is the promise of the American Founding. When our children, as Lincoln explained, look

through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are.

We assume our civic responsibility when we realize that the Declaration’s maxim of human equality invites our participation, that America is a continuous, rather than a stagnant, story of hope. We have certainly had our setbacks and committed our sins, and that is part of the story. But our contributions to the cause of human freedom are significant, and America’s overall trajectory, despite its ebbs and flows, has been toward a greater realization of our principles.

As storytellers of our history, museums bear unique responsibility in fostering citizens capable of deliberation and self-government.

That progression was renewed by Lincoln and his generation of soldiers, and it was originally made possible by the Founders who first declared our national purpose and creed: the idea that “all men are created equal.” The hope of America is not simply in those principles, but in the American people themselves. There is hope in the fact that we are asked to join in the experiment in self-government, to prove to ourselves, and to the world, that we are worthy of preserving it and perhaps even further perfecting it. But our institutions must cultivate these virtues, and as storytellers of our history, museums bear unique responsibility in fostering citizens capable of deliberation and self-government.

Historic sites like Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, and Colonial Williamsburg are places that connect America, from Pennsylvania to Virginia. The Miracle of Philadelphia—the Constitution—has its symbolic birthplace in Virginia, and largely through the mind of James Madison. The primary purpose of the document he imagined is to protect and form a nation of citizens capable of self-government, “to ensure the blessings of liberty for ourselves and our posterity.” That is the shared aim of our historic sites.

In this time of immense political discord, we must choose whether to defend the birthplaces of our national character, so that they may remain in the hearts of our children. We are worthy of fulfilling Madison’s vision for this nation and are capable of the demands of self-government.

“Whitehead’s satire takes aim … at a capitalist system that senses the profits to be made from proclaiming that systemic racism is a thing of the past.”

The post B-Sides: Colson Whitehead’s “Apex Hides the Hurt” appeared first on Public Books.

In Rome, one doesn’t have to look terribly hard to find ancient buildings. But even in the Eternal City, not all ancient buildings have come down to us in equally good shape, and practically none of them have held up as well as the Pantheon. Once a Roman temple and now a Catholic church (as well as a formidable tourist attraction), it gives its visitors the clearest and most direct sense possible of the majesty of antiquity. But how has it managed to remain intact for nineteen centuries and counting when so much else in ancient Rome’s built environment has been lost? Ancient-history Youtuber Garrett Ryan explains that in the video above.

“Any answer has to begin with concrete,” Ryan says, the Roman variety of which “cured incredibly hard, even underwater. Sea water, in fact, made it stronger.” Its strength “enabled the creation of vaults and domes that revolutionized architecture,” not least the still-sublime dome of the Pantheon itself.

Another important factor is the Roman bricks, “more like thick tiles than modern rectangular bricks,” used to construct the arches in its walls. These “helped to direct the gargantuan weight of the rotunda toward the masonry ‘piers’ between the recesses. And since the arches, made almost entirely of brick, set much more quickly than the concrete fill in which they were embedded, they stiffened the structure as it rose.”

This hasn’t kept the Pantheon’s floor from sinking, cracks from opening in its walls, but such comparatively minor defects could hardly distract from the spectacle of the dome (a feat not equaled until Filippo Brunelleschi came along about 1300 years later). “The architect of the Pantheon managed horizontal thrust — that is, prevented the dome from spreading or pushing out the building beneath it – by making the wall of the rotunda extremely thick and embedding the lower third of the dome in their mass.” Even the oculus at the very top strengthens it, “both by obviating the need for a structurally dangerous crown and through its masonry rim, which functioned like the keystone of an arch.” We may no longer pay tribute to the gods or emperors to whom it was first dedicated, but as an object of architectural worship, the Pantheon will surely outlast many generations to come.

Related content:

The Beauty & Ingenuity of the Pantheon, Ancient Rome’s Best-Preserved Monument: An Introduction

How to Make Roman Concrete, One of Human Civilization’s Longest-Lasting Building Materials

A Street Musician Plays Pink Floyd’s “Time” in Front of the 1,900-Year-Old Pantheon in Rome

How the World’s Biggest Dome Was Built: The Story of Filippo Brunelleschi and the Duomo in Florence

The Mystery Finally Solved: Why Has Roman Concrete Been So Durable?

Building The Colosseum: The Icon of Rome

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A funny thing happened on the way to the 15th century…

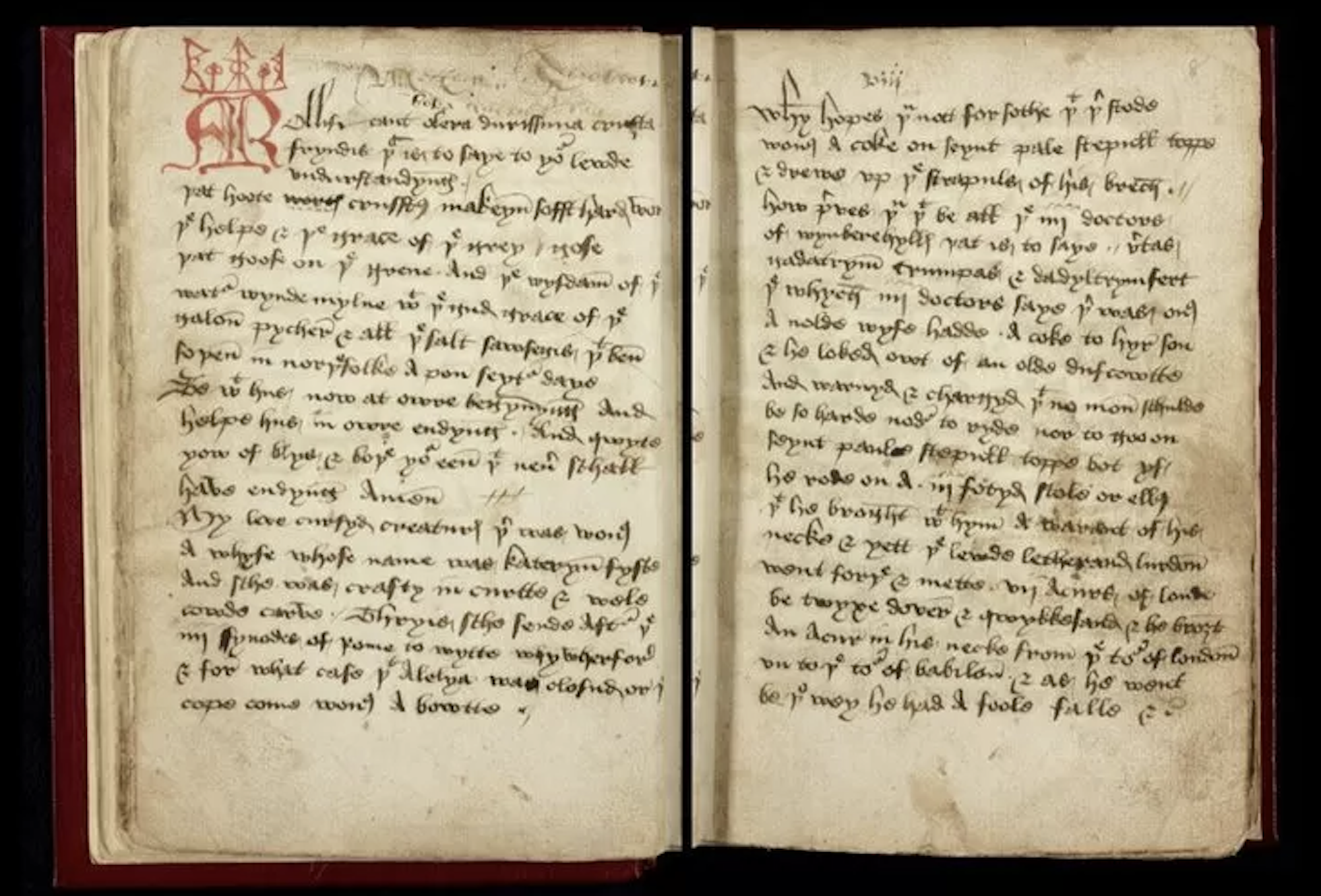

Dr. James Wade, a specialist in early English literature at the University of Cambridge, was doing research at the National Library of Scotland when he noticed something extraordinary about the first of the nine miscellaneous booklets comprising the Heege Manuscript.

Most surviving medieval manuscripts are the stuff of high art. The first part of the Heege Manuscript is funny.

The usual tales of romance and heroism, allusions to ancient Rome, lofty poetry and dramatic interludes… even the dashing adventures of Robin Hood are conspicuously absent.

Instead it’s awash with the staples of contemporary stand up comedy – topical observations, humorous oversharing, roasting eminent public figures, razzing the audience, flattering the audience by busting on the denizens of nearby communities, shaggy dog tales, absurdities and non-sequiturs.

Repeated references to passing the cup conjure an open mic type scenario.

The manuscript was created by cleric Richard Heege and entered into the collection of his employers, the wealthy Sherbrooke family.

Other scholars have concentrated on the manuscript’s physical construction, mostly refraining from comment on the nature of its contents.

Dr. Wade suspects that the first booklet is the result of Heege having paid close attention to an anonymous traveling minstrel’s performance, perhaps going so far as to consult the performer’s own notes.

Heege quipped that he was the author owing to the fact that he “was at that feast and did not have a drink” – meaning he was the only one sober enough to retain the minstrel’s jokes and inventive plotlines.

Dr. Wade describes how the comic portion of the Heege Manuscript is broken down into three parts, the first of which is sure to gratify fans of Monty Python and the Holy Grail:

…it’s a narrative account of a bunch of peasants who try to hunt a hare, and it all ends disastrously, where they beat each other up and the wives have to come with wheelbarrows and hold them home.

That hare turns out to be one fierce bad rabbit, so much so that the tale’s proletarian hero, the prosaically named Jack Wade, worries she could rip out his throat.

Dr. Wade learned that Sir Walter Scott, author of Ivanhoe, was aware of The Hunting of the Hare, viewing it as a sturdy spoof of high minded romance, “studiously filled with grotesque, absurd, and extravagant characters.”

The killer bunny yarn is followed by a mock sermon – If thou have a great black bowl in thy hand and it be full of good ale and thou leave anything therein, thou puttest thy soul into greater pain – and a nonsense poem about a feast where everyone gets hammered and chaos ensues.

Crowd-pleasing material in 1480.

With a few 21st-century tweaks, an enterprising young comedian might wring laughs from it yet.

(Paging Tyler Gunther, of Greedy Peasant fame…)

As to the true author of these routines, Dr. Wade speculates that he may have been a “professional traveling minstrel or a local amateur performer.” Possibly even both:

A ‘professional’ minstrel might have a day job and go gigging at night, and so be, in a sense, semi-professional, just as a ‘travelling’ minstrel may well be also ‘local’, working a beat of nearby villages and generally known in the area. On balance, the texts in this booklet suggest a minstrel of this variety: someone whose material includes several local place-names, but also whose material is made to travel, with the lack of determinacy designed to comically engage audiences regardless of specific locale.

Learn more about the Heege Manuscript in Dr. Wade’s article, Entertainments from a Medieval Minstrel’s Repertoire Book in The Review of English Studies.

Leaf through a digital facsimile of the Heege Manuscript here.

Related Content

Killer Rabbits in Medieval Manuscripts: Why So Many Drawings in the Margins Depict Bunnies Going Bad

A List of 1,065 Medieval Dog Names: Nosewise, Garlik, Havegoodday & More

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

In 1978, the University of Chicago Press journal Signs published a short essay introducing Mary Wollstonecraft’s lost anthology of prose and poetry she had published “for the improvement of young women.” Wollstonecraft’s anthology reproduced edifying fables and poetry; excerpted from the Bible, Shakespeare, and Milton; and included four Christian prayers Wollstonecraft had authored herself. Among the last is a lengthy “Private Morning Prayer” which reads, in part:

Though knowest whereof I am made, and rememberest that I am but dust: self-convicted I prostrate myself before thy throne of grace, and seek not to hide or palliate my faults; be not extreme to mark what I have done amiss—still allow me to call thee Father, and rejoice in my existence, since I can trace thy goodness and truth on earth, and feel myself allied to that glorious Being who breathed into me the breath of life, and gave me a capacity to know and to serve him.

Though Wollstonecraft is now regarded a canonical thinker in the fields of history, political science, and gender studies, secular feminist scholars still struggle to make sense of her religiosity. Many suggest, as Moira Ferguson did in her 1978 Signs essay, that Wollstonecraft’s own skepticism grew as she crafted her more influential political work. Meanwhile, religious thinkers tend to ignore her religiosity, subscribing to the selfsame interpretation of her as a duly secular proto-feminist.

Enter Modern Virtue: Mary Wollstonecraft and a Tradition of Dissent (Oxford) by Emily Dumler-Winckler, the first adequately theological treatment of Wollstonecraft’s pedagogical, social, and political thought. In a beautifully written, deeply learned, and insightful book, the St. Louis University theologian maintains that there is far greater continuity throughout Wollstonecraft’s work than scholars realize. The imitatio Christi commended in her early publications, including the Female Reader, is the key that unlocks her entire corpus. Deftly employing knowledge of Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, and Aquinas, but also Burke, Rousseau, Kant, Hume, and Paine, Dumler-Winckler situates Wollstonecraft in the Western canon as the seminal philosophical and theological thinker she rightly is.

In a beautifully written, deeply learned, and insightful book, the St. Louis University theologian maintains that there is far greater continuity throughout Wollstonecraft’s work than scholars realize.

Dumler-Winckler is at her best in revealing the kinship between Wollstonecraft and the pre-moderns, and distinguishing her from contemporaries like Kant. Such scholarly care helps Dumler-Winckler show how Wollstoncecraft’s thinking about virtue, justice, and friendship can inform those who resist various racial and economic injustices today.

However, Dumler-Winckler is less convincing in her efforts to distinguish Wollstonecraft’s pre-modern insights from those she dubs (and derides) “virtues’ defenders,” namely, Alasdair MacIntyre, Stanley Hauerwas, and Brad Gregory. Certainly, their thought—like the “virtue despisers” she more charitably challenges—would be well served by the rich encounter with Wollstonecraft that her book offers. But given Dumler-Winckler’s own judicious critiques of our modern ills, these “defenders” (especially Gregory) may be more friends than the foes she imagines.

Cultivating the Virtues through the Moral Imagination

Given Wollstonecraft’s sharp critique of Edmund Burke’s (prescient) condemnation of the French Revolution—as well as her Enlightenment-era claim of “natural rights” for women—Wollstonecraft has long been regarded a paradigmatically liberal thinker: akin to a female Thomas Paine, a feminist John Locke, a proto-Kantian. However, some scholars in recent decades have rejected these inapt comparisons, with most now placing her, rightly in my view, in the civic republican tradition that dates to Cicero. This reexamination of Wollstonecraft’s thought has also allowed for greater scrutiny of her argument with Burke over the French Revolution, with some now seeing far more affinity between the two English thinkers than was previously thought.

Dumler-Winckler’s 2023 book deepens these insights by foregrounding Wollstonecraft’s early pedagogical texts as the key that unlocks her account of the virtues, which itself is the prism through which to view her entire corpus. Throughout Modern Virtue, Dumler-Winckler strongly contests the view that Wollstonecraft’s account of virtue resembles that of the rationalist Kant, or the “naked” rationalism of the French revolutionaries Burke rightly scolds. Early on, Wollstonecraft writes: “Reason is indeed the heaven-lighted lamp in man, and may safely be trusted when not entirely depended on; but when it pretends to discover what is beyond its ken, it . . . runs into absurdity.” As Dumler-Winckler shows, respect for the ennobling human capacity for reason and its limits can be found throughout her work.

It’s in the rich Christian tradition especially that Wollstonecraft finds dynamic resources to bear on her “modern” subjects (abolition and women’s education, in particular).

But Dumler-Winckler also ably distinguishes the proto-feminist from the “sentimentalism” of Hume, the “voluntarism” of some Protestant contemporaries, and the “traditionalism” of Burke. Dumler-Winckler finds the golden mean by looking beyond the moderns with whom Wollstonecraft is too hastily classified to show her kinship with ancient and medieval thinkers, especially Aristotle and Aquinas. It’s in the rich Christian tradition especially that Wollstonecraft finds dynamic resources to bring to bear on her “modern” subjects (abolition and women’s education, in particular)—even as the late-eighteenth-century thinker refines the tradition for the “revolution in female manners” she seeks to inspire. Thus, the seemingly incongruous subtitle: “a Tradition of Dissent.”

“The main business of our lives is to learn to be virtuous,” the pedagogue wrote in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787). For Wollstonecraft as for Aristotle and especially Aquinas, argues Dumler-Winckler, one learns to be virtuous through the gradual refinement of all the faculties in a dynamic engagement of the imagination, understanding, judgment, and affections—especially through imitating the patterns of Christ-like moral exemplars. “Teach us with humble awe to imitate the divine patterns and lure us to the paths of virtue,” Wollstonecraft writes. One “puts on righteousness,” then, not ultimately as a rule obeyed, a ritual practiced, or a philosophical tenet held, even as obedience, rituals, and understanding are, for Wollstonecraft, all essential components.

Rather, one “puts on righteousness” as a kind of “second nature,” which is the refinement and cultivation of raw, unformed appetites (i.e, “first nature”). Wollstonecraft artfully employs Burke’s metaphor of the “wardrobe of the moral imagination” to depict the way in which cultivation of the virtues refines one’s “taste” in particular matters. “For Wollstonecraft, nature serves as a standard for taste, only insofar as the passions, appetites, and faculties of reason, judgment, and imagination are refined by second natural virtues. . . . [I]t is never the gratification of depraved appetites, but rather exalted appetites and minds . . . which are to govern our relations.”

In imitating Christ-like exemplars from an early age, we develop the the moral virtues that perfect our relation with God and others—being crafted and crafting oneself, in turn. “Whatever tends to impress habits of order on the expanding mind may be reckoned the most beneficial part of education,” Wollstonecraft writes in the introduction to the Female Reader, “for by this means the surest foundation of virtue is settled without struggle, and strong restraints knit together before vice has introduced confusion.” Pointing to this dialectical design, Dumler-Winckler shows how Wollstonecraft wished for Scripture and Shakespeare to “gradually form” girls’ taste so that they might “learn not ‘what to say’ but rather how to read, think, and even pray well, and how to exercise their reason, cultivate virtue, and refine devotional taste.” Schooling the moral imagination through imitation was the key to acquiring virtue for both Aristotle and Wollstonecraft—but so was making virtue one’s own: “[W]e collectively inherit, tailor, and design [the virtues] as a garb in the wardrobe of a moral imagination.”

Wollstonecraft’s argument with Burke, then, concerns not the evident horrors and evils of the Revolution itself (in which she agrees with him) but the causes of such evils. For Wollstonecraft, the monarchical French regime Burke extols had become deeply corrupt, with rich and poor loving not true liberty but honors and property. The French peasants (and the revolutionaries that emboldened them) thus lacked the virtues that would allow them to respond to injustice in a virtuous way: “The slave unwittingly becomes the master, the tyrannized a tyrant, the oppressed an oppressor.” “Absent virtue,” Dumler-Winckler insightfully writes, “protest unwittingly replicates the injustice it protests. For Wollstonecraft, true virtue is revolutionary because it enables one to justly protest injustice, and so not only to criticize but to embody an alternative.” Throughout the text, Dumler-Winckler exhorts those who would critique various injustices today to showcase, in their particular circumstances and unique oppressions, virtuous alternatives.

Women’s Rights for the Cause of Virtue

Just as Augustine distinguished true Christian virtue from its pagan semblances, Dumler-Winckler tells us, Wollstonecraft distinguishes true virtue from its “sexed semblances,” especially in the thought of Burke and Rousseau. For the latter two, human excellence was a deeply gendered affair. For Wollstonecraft, however, virtue is not “sexed”—even as men and women, with distinctive procreative capacities and physical strength, clearly are. Dumler-Winckler yet again turns to Aristotle and Aquinas as those who “supply the material” for Wollstonecraft to call upon women to imitate Christ and live according to their rightful dignity as imago Dei. Dumler-Winckler’s own words could summarize her important book: “The affirmation of women’s ability to recognize, identify with, and even emulate the divine attributes has been so crucial for the affirmation of their humanity and equality, it may be considered a founding impetus for traditions of modern feminism.”

Wollstonecraft knew that women’s education and role in society needed to be reimagined. Dumler-Winckler writes that “unlike most of her predecessors, premodern and modern alike, . . . Wollstonecraft could see that growing in likeness of God would require a ‘revolution in female manners’ and a rejection of ‘sexed virtues.’” Mrs. Mason, the Christ-like protagonist in Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories, taught her female pupils to think for themselves “and rely only on God.” Mason’s advice did not commend the Kantian autonomy so often extolled today, but rather “virtuous independence.” Mason taught: “[W]e are all dependent on each other; and this dependence is wisely ordered by our Heavenly Father, to call forth many virtues, to exercise the best affections of the human heart, and fix them into habits.”

And thus we come to the rationale behind Wollstonecraft’s late-eighteenth-century appeal for women’s rights. It was an appeal “for the cause of virtue,” as Dumler-Winckler quotes the proto-feminist again and again. Wollstonecraft grounded rights in the imago Dei, viewing them as both important protections against arbitrary and unjust domination, and specifications of justice’s demands: “what is due, owed, or required to set a particular relationship right,” as Dumler-Winckler nicely puts it. Unlike the Hobbesian Jacobins, Wollstonecraft recognized that “liberty comes with attendant duties, constraints, and social obligations at every step.”

Recognizing how Wollstonecraft advocated rights on the basis of Christian theological anthropology, not secular Enlightenment ideals, it is odd then that Dumler-Winckler picks a fight with the likes of Alasdair MacIntyre, Stanley Hauerwas, and especially Notre Dame historian Brad Gregory. It is true that in his 2012 Unintended Reformation, Gregory laments, in Dumler-Winckler’s words, “the eclipse of an ethics of virtue with a culture of rights,” but unlike MacIntyre and Hauerwas, who reject rights as a quintessentially liberal phenomenon, Gregory endorses an older grounding for rights. But this is precisely what Dumler-Winckler has shown Wollstonecraft offers: the good and right held together, just as, both happily acknowledge, Catholic social teaching does today.

Wollstonecraft grounded rights in the imago Dei, viewing them as both important protections against arbitrary and unjust domination, and specifications of justice’s demands.

Unfortunately, however, modern rights theories have followed not Wollstonecraft or CST but the “conceptions of autonomy and self-legislation” that both reject. Though Wollstonecraft’s view of “liberty is not, as Burke fears, a license to do whatever one pleases or as Gregory fears ‘a kingdom of whatever,’” that surely is a prevailing view of liberty today. Indeed, it manifests itself (in Gregory’s view) in acquisitive consumerism, “an environmental nightmare,” “exploitative (and often brutally gendered)” impact on workers, the decline in the “culture of care” and much, much more, about which Dumler-Winckler and Gregory (and I) agree! But more crucial, perhaps, is a common solution: if “disordered loves are at root, Wollstonecraft suggests, a matter of idolatry,” the remedy depends, according to Dumler-Winckler, on “their reordering, on the cultivation of what Wollstonecraft considers ‘the fairest virtues,’ namely benevolence, friendship, and generosity. . . . Not to banish love and friendship from politics, . . . but to refine earthly loves.”

Dumler-Winckler and I disagree about some of the practical implications of Wollstonecraft’s vision today. She sees unjust essentializing in the TERF movement; I, in the gender ideology against which TERFS rally. She hails Kamala Harris as an exemplar, I, Justice Barrett. But that we share a common understanding—and indeed an intellectual framework—that each person “learning to be virtuous” can transform a society for the common good is itself a great advance from the MacIntyrian lament. It is one for which she and I can both happily thank an inspiring and insightful eighteenth-century autodidact, one who should be more widely read—and carefully studied—today.

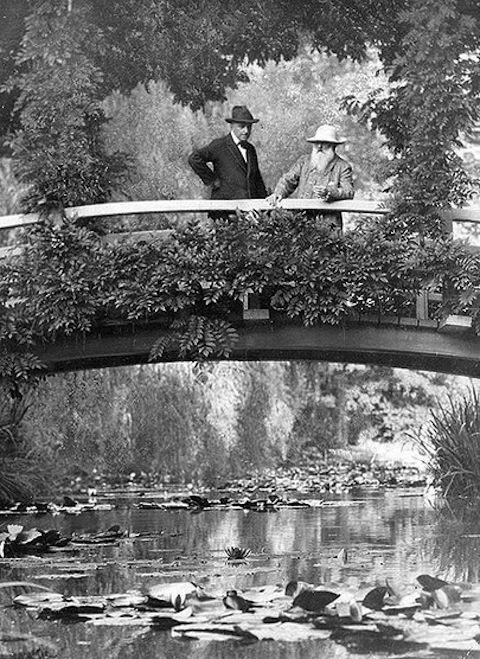

What could be more charmingly idyllic than a glimpse of snowy-bearded Impressionist Claude Monet calmly painting en plein-air in his garden at Giverny?

A wide-brimmed hat and two luxuriously large patio-type umbrellas provide shade, while the artist stays cool in a pristine white suit.

His canvas is off camera for the most part, but given the coordinates, it seems safe to assume the subject’s got something to do with the famous Japanese footbridge spanning Monet’s equally famous lily pond.

The sun’s still high when he puts down his cat’s tongue brush and heads back to the house with his little dog at his heels, no doubt anticipating a delicious, relaxed luncheon.

Even in black-and-white, it’s an irresistible pastoral vision!

And quite a contrast to the recent scene some 300 km away in Ypres, where German troops weaponized chlorine gas for the first time, releasing it in the Allied trenches the same year the above footage of Monet was shot.

Lendon Payne, a British sapper, was an eyewitness to some of the mayhem:

When the gas attack was over and the all clear was sounded I decided to go out for a breath of fresh air and see what was happening. But I could hardly believe my eyes when I looked along the bank. The bank was absolutely covered with bodies of gassed men. Must have been over 1,000 of them. And down in the stream, a little bit further along the canal bank, the stream there was also full of bodies as well. They were gradually gathered up and all put in a huge pile after being identified in a place called Hospital Farm on the left of Ypres. And whilst they were in there the ADMS came along to make his report and whilst he was sizing up the situation a shell burst and killed him.

The early days of the Great War are what spurred director Sacha Guitry, seen chatting with Monet above, to visit the 82-year-old artist as part of his 22-minute silent documentary, Ceux de Chez Nous (Those of Our Land).

The entire project was an act of resistance.

With German intellectuals trumpeting the superiority of Germanic culture, the Russian-born Guitry, a successful actor and playwright, sought out audiences with aging French luminaries, to preserve for future generations.

In addition to Monet, these include appearances by painters Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas, sculptor Auguste Rodin, writer Anatole France, composer Camille Saint-Saens, and actor Sarah Bernhardt.

Although Ceux de Chez Nous was silent, Guitry carefully documented the content of each interview, revisiting them in 1952 for the expanded version with commentary, below.

Beneath his placid exterior, Monet, too, was quite consumed by the horrors unfolding nearby.

James Payne, creator of the web series Great Art Explained, views Monet’s final eight water lily paintings as a “direct response to the most savage and apocalyptic period of modern history…a war memorial to the millions of lives tragically lost in the First World War.”

In 1914, Monet wrote that while painting helped take his mind off “these sad times” he also felt “ashamed to think about my little researches into form and colour while so many people are suffering and dying for us.”

As curator Ann Dumas notes in RA Magazine:

The peace of his garden was sometimes shattered by the sound of gunfire from the battlefields only 50 kilometres away. His stepson was fighting at the front and his own son Michel was called up in 1915. Many of the inhabitants of Giverny fled to safety but Monet stayed behind: “…if those savages must kill me, it will be in the middle of my canvases, in front of all my life’s work.” Painting was what he did and he saw it, in a way, as his patriotic contribution. A group of paintings of the weeping willow, a traditional symbol of mourning, was Monet’s most immediate response to the war, the tree’s long, sweeping branches hanging over the water, an eloquent expression of grief and loss.

Related Content

1540 Monet Paintings in a Two Hour Video

Why Monet Painted The Same Haystacks 25 Times

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

No American who came of age in the nineteen-eighties — or in most of the seventies or nineties, for that matter — could pretend not to understand the importance of the mall. Edina, Minnesota’s Southdale Center, which defined the modern shopping mall’s enclosed, department store-anchored form, opened in 1956. Over the decades that followed, living patterns suburbanized and developers responded by plunging into a long and profitable orgy of mall-building, with the result that generations of adolescents lived in reasonably easy reach of such a commercial institution. Some came to shop and others came to work, but if Hugh Kinniburgh’s documentary Mall City is to be believed, most came just to “hang out.”

Introduced as “A SAFARI TO STUDY MALL CULTURE,” Mall City consists of interviews conducted by Kinniburgh and his NYU Film School collaborators during one day in 1983 at the Roosevelt Field Mall on Long Island. Unsurprisingly, their interviewees tend to be young, strenuously coiffed, and dressed with studied nonchalance in striped T-shirts and Members Only-style windbreakers.

A trip to the mall could offer them a chance to expand their wardrobe, or at the very least to calibrate their fashion sense. You go to the mall, says one stylish young lady, “to see what’s in, what’s out,” and thus to develop your own style. “You look for ideas,” as the interviewer summarizes it, “and then recombine them in your own way, try to be original.”

One part of the value proposition of the mall was its shops; another, larger part was the presence of so many other members of your demographic. In explaining why they come to the mall, some teenagers dissimulate less than others: “It’s like, where the cool people are at,” says one girl, with notable forthrightness. “You’re fakin’ this all. I mean, you’re just tryin’ to meet people.” Kinniburgh and his crew chat with a group of barely adolescent-looking boys — each and every one smoking a cigarette — about what encountering girls has to do with the time they spend hanging out at the mall. One answers without hesitation: “That’s the main reason.” (Yet these labors seem often to have borne bitter fruit: as one former employee and current hanger-out puts it, “Mall relationships don’t last.”)

Opened just two months after Southdale Center, Roosevelt Field is actually one of America’s most venerable shopping malls. (It also possesses unusual architectural credibility, having been designed by none other than I. M. Pei.) By all appearances, it also managed to reconstitute certain functions of a genuine urban social space — or at least it did forty years ago, at the height of “mall culture.” Asked for his thoughts on that phenomenon, one post-hippie type describes it as “probably the wave of the future. Maybe the end of the future, the way things are going.” Here in that future, we speak of shopping malls as decrepit, even vanishing relics of a lost era, one with its own priorities, its own folkways, even its own accents. Could such a variety of pronunciations of the very word “mall” still be heard on Long Island? Clearly, further fieldwork is required.

Related content:

Punks, Goths, and Mods on TV (1983)

The Walkman Turns 40: See Every Generation of Sony’s Iconic Personal Stereo in One Minute

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read more in this series: Cotton Capital

More and more institutions are commissioning investigations into their historical links to slavery – but the fallout at one Cambridge college suggests these projects are meeting growing resistance

Continue reading...

After our antepenultimate Iliad episode comes... the penultimate episode! In Book 23, Hector is dead, and Achilles mourns Patroclus, who comes to Achilles in a dream and demands a funeral. So Achilles organizes funeral games: chariot and foot races, boxing and wrestling, and more. The Argives compete, and contend over the justice of their competition. We ask: why does Homer's description Continue Reading …

The post Combat & Classics Ep. 81 Homer’s “Iliad” Book 23 first appeared on The Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast.“I’m very skeptical about the ability of people in positions of power and privilege—including intellectuals—to name truths about the world.”

The post Don’t Save Yourself, Save the World: A Dialogue with Vincent Lloyd appeared first on Public Books.

We all know music when we hear it — or at least we think we do — but how, exactly, do we define it? “Imagine you’re in a jazz club, listening to the rhythmic honking of horns,” says the narrator of the animated TED-Ed video above. “Most people would agree that this is music. But if you were on the highway, hearing the same thing, many would call it noise.” Yet the closer we get to the boundary between music and noise, the less clear it gets. The composer John Cage, to whose work this video provides an introduction, spent his long career in those very borderlands: he “gleefully dared listeners to question the boundaries between music and noise, as well as sound and silence.”

The best-known example of this larger endeavor is “4’33”,” Cage’s 1952 “solo piano piece consisting of nothing but musical rests for four minutes and thirty-three seconds.” Though known as a “silent” composition, it actually makes its listeners focus on all the incidental sounds around them: “Could the opening and closing of a piano lid be music? What about the click of a stopwatch? The rustling, and perhaps even the complaining, of a crowd?”

A few years later, he implicitly asked similar questions about what does and does not count as music to television viewers across America by performing “Water Walk” — whose instruments included “a bathtub, ice cubes, a toy fish, a pressure cooker, a rubber duck, and several radios” — on CBS’ I’ve Got a Secret.

Many who watched that broadcast in 1960 would have asked the same question: “Is this even music?” This may have well have been the outcome for which Cage himself hoped. “Like the white canvases of his painting peers” in that same era, his work “asked the audience to question their expectations about what music was.” As he explored more and more deeply into the territory of unconventional methods of instrumentation, notation, and performance, he drifted farther and farther from the composer’s traditional task: “to organize sound in time for a specific intentional purpose.” Seven decades after “4’33”,” some still insist that John Cage’s work isn’t music — but then, some say the same about Kenny G.

Related content:

Watch John Cage Play His “Silent” 4’33” in Harvard Square, Presented by Nam June Paik (1973)

The Music of Avant-Garde Composer John Cage Now Available in a Free Online Archive

John Cage Performs “Water Walk” on US Game Show I’ve Got a Secret (1960)

An Impressive Audio Archive of John Cage Lectures & Interviews: Hear Recordings from 1963-1991

How to Get Started: John Cage’s Approach to Starting the Difficult Creative Process

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Editor’s note: This year is the second time that Americans celebrate Juneteenth as a national holiday. At Public Discourse this week, we offer essays that look back on Juneteenth’s history, and look ahead to consider its place in America’s self-understanding.

Juneteenth, now a national holiday, is an opportunity for us to engage in a conversation on freedom and the American Project in a way that we have rarely, if ever, done as a national community. This might come as a surprise to many—after all, we commemorate and celebrate the Fourth of July every year with barbecues and fireworks, and this is certainly a great freedom celebration. But July Fourth can bring up mixed emotions for some of us—and I am not at all alone among African Americans who feel torn on this date.

Framing the Fourth

We are proud to be American, and do not long to live anywhere else. My father and grandfather were both in the military for much of their lives—my father having had the honor of serving on Air Force One and Air Force Two for years before retiring at the rank of Chief Master Sergeant. But we also remember, in some ways are haunted by, the fact that at that first July Fourth, and for far too many after that, we could not exercise the freedom being celebrated all around us.

This has created some ambivalence about how to think about and commemorate the Fourth. Consider, for example, our tentative groping as parents for the best way to observe this day in our home. It was another July Fourth holiday and our children were still young, perhaps six and nine years old. I am a scholar doing historical work on race, so it is an occupational hazard for me to think deeply and carefully about such commemorations. What is the essence of the July Fourth celebration? Where were we, as African Americans, in the memory and memorialization of this world historical event? Yes, we had read of Crispus Attucks, Phillis Wheatley, and others who advocated, bled, and died for this new America—but the liberty secured for so many did not extend to our ancestors—not at that time.

And so, on that day years ago, sitting around the table, about to partake of our special July Fourth meal, we first read aloud from parts of Frederick Douglass’s speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” It is an intense text, powerful and bittersweet, as Douglass recounts the glories of the revolution while at the same time mourning the fact that the vast majority of Black Americans were still in chains. My oldest daughter, eyes wide as she listened, asked in a pleading voice: “But we can still have a happy Fourth of July, right?” I was torn, trying to determine how best to thread the needle between celebration and remembrance of a difficult past.

I ended up assuring her that yes, indeed, we could and would have a happy Fourth of July. The preliminary reading was to bring to our remembrance the path we have come through in this country, to remember and respect the work it has taken to bring us to where we are today.

Juneteenth, coming as it does just weeks before July Fourth, provides a perfect opportunity for us—both individually and collectively—to engage in a season of contemplating and celebrating the complexities and nuances, highs and lows, of this American experiment that has at its core the achievement of freedom.

My daughter’s question: “But we can still have a happy Fourth of July, right?” rings in my ears across the years. I think, in retrospect, I could have framed the day more fruitfully if I had introduced it as a remembrance—one that is part of a larger conversation on freedom that begins each year with the commemoration of Juneteenth a few weeks earlier, and culminates on July Fourth.

Juneteenth, coming as it does just weeks before July Fourth, provides a perfect opportunity for us—both individually and collectively—to engage in a season of contemplating and celebrating the complexities and nuances, highs and lows, of this American experiment that has at its core the achievement of freedom. This dialectical pairing of the two holidays is important, I would go so far as to say necessary, for a people who have yet to develop a vocabulary and practice for discussing its complicated relationship with the past—a past that includes just as much slavery, racism, and injustice as it does freedom and the pursuit of happiness.

An Annual Conversation

The annual conversation I envision taking place between Juneteenth and July Fourth should include a healthy representation of Black voices from the past who can help us to narrate and pass on our national story of freedom-seeking across the centuries. Central to this conversation are the extraordinary ideas contained in the Declaration:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

This beginning of the republic held great promise, but the vast majority of Africans in America did not yet benefit from the promises of 1776, despite the fact that many of us had supported the Revolution with both the pen and the sword.

One of these, Phillis Wheatley, was kidnapped from Africa when she was about seven years old and was a poetic genius who supported the Revolution from the home of her owners in Boston. In her letters she compared white Americans to the Egyptians who held the people of Israel in bondage. She wrote: “in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and . . . that . . . same Principle lives in us.” She even penned a letter and poem of support addressed to George Washington when he was commander in chief of the Continental Army, cheering him and others on to win independence from Britain. (Washington received her letter and poem, was impressed with her, and responded in kind by letter. See the exchange here.)

Nearly one hundred year later, Frederick Douglass made his famous speech concerning the Fourth of July when he was invited by white Americans to deliver a celebratory speech commemorating the holiday in 1852. He had escaped a brutal slave owner fourteen years earlier, the wounds on his back scarred over, still visible. He brought the incongruity of the invitation to their awareness, saying:

This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

Almost a decade later, the issue of slavery finally came to a head with the Civil War and was followed by emancipation with the Union’s victory. Firsthand accounts from formerly enslaved people in Texas on that original Juneteenth help to bring alive the excitement, anticipation, and dynamism of this moment. Tempie Cummins explains how the newly freed resisted the slave owners who ignored the news of emancipation:

When freedom was declared, master wouldn’ tell them, but mother she hear him tellin’ missus that the slaves was free but they didn’t know it and he’s not going tell ’em till he makes another crop or two. When mother hear that she say she slip out the chimney corner and crack her heels together four times and shouts, ‘I’s free, I’s free.’ Then she runs to the field, against master’s will and told all the other slaves and they quit work.

Felix Haywood has one of the most vibrant and philosophical reflections on how he experienced this new freedom and what it meant to him. He had worked as a sheep herder and cowpuncher and was about ninety-two years old when he was interviewed. When he was asked how they knew that freedom had finally come he responded: “How did we know it! Hallelujah broke out—. . . ” He then burst into song and went on to share the feeling of exhilaration that pervaded the community:

Everybody went wild. We all felt like heroes and nobody had made us that way but ourselves. We was free. Just like that, we was free . . . right off colored folks started on the move. They seemed to want to get closer to freedom, so they’d know what it was—like it was a place or a city. . . .

Haywood’s image of freedom as a “place or a city” evokes larger questions and conversations about what freedom ultimately is, and how we’ll know it once we’ve attained it. Indeed, as his narrative continues, he hints at the power these questions exercised over the newly emancipated. At first, he and others assumed that they would now be rich, even richer than the whites who had owned them because they were the ones who really knew how to do the work. But then he notes: “We soon found out that freedom could make folks proud but it didn’t make ’em rich.” Haywood’s reflections here highlight the many complex dimensions of freedom—the physical dimension being just the first step toward the development of political, moral, and intellectual resources and virtues that allow us to flourish.

New National Tradition

Haywood’s reflections on the expectations and realities of freedom evoke the many times when we long for something great, but it turns out to be more compelling in the imagination than in reality. Hard work often follows once we have achieved our long-anticipated goal. This brings us to the current state of our national conversation on freedom. I think it no coincidence that the decision to make Juneteenth a national holiday followed right on the heels of Black protest that swept across the country in 2020. After much striving and protest that has reshaped the national conversation on race, what will we do now that Juneteenth has achieved the status of being a national holiday?

While the national observance is still new and nationwide traditions have yet to be formed, now is the time to initiate, to carefully cultivate, a new kind of conversation on freedom poised between the promises of the Declaration and the fitful realization of those promises across the centuries.

If we are not careful, Juneteenth may simply become something that makes African Americans “proud without making us rich,” to paraphrase Felix Haywood. Our pride in recognizing and celebrating Juneteenth may rest there without going any further. We may be left “feeling good” without coming any closer to being “rich” in the deepest sense of that word. But what we desire is the kind of richness that allows us all to live fuller lives—whatever our race or ethnicity—as we seek to better exercise and enjoy the freedoms we have fought for.

There is also the danger that Juneteenth will become a holiday observed by a small segment of the population while being largely ignored by the majority of Americans. I sincerely hope this will not be the case. While the national observance is still new and nationwide traditions have yet to be formed, now is the time to initiate, to carefully cultivate, a new kind of conversation on freedom poised between the promises of the Declaration (celebrated on the Fourth) and the fitful realization of those promises across the centuries (which emerged more fully on June 19, 1865)—and that continue to unfold in new ways today. My hope is that these weeks between Juneteenth and July Fourth will become an extended time of conversation, celebration, and contemplation of our long road to freedom.

Editor’s note: This year is the second time that Americans celebrate Juneteenth as a national holiday. At Public Discourse this week, we offer essays that look back on Juneteenth’s history, and look ahead to consider its place in America’s self-understanding.

Juneteenth is a linguistic compression of the date “June Nineteenth,” with the particular June 19th in view being June 19, 1865. The American Civil War was practically over by that date—the principal Confederate field army under Robert E. Lee had surrendered in Virginia on April 9, 1865, followed by the surrenders of other Confederate forces and the capture of fleeing Confederate president Jefferson Davis on May 10th. But only practically. The United States government had never recognized the Confederacy as a legal entity, and so there were no peace talks or treaty signings to mark a single end-point to the war; the Confederacy simply expired, and did so unevenly, from place to place. In Texas, there were still enough in the way of organized Confederate forces to fight a pitched battle, at Palmito Ranch on May 12th. Palmito Ranch was not a very large or significant battle, but it ended in the withdrawal of Union soldiers back to the southern Texas port of Brownsville, which they had occupied since 1863. Anyone who wanted to declare the war over might find themselves in more danger than they had imagined.

The same thing was true for slavery, which was the principal cause that triggered the war. President Abraham Lincoln had issued an Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, that declared “forever free” all the slaves in those parts of the breakaway Southern Confederacy not yet returned to Union control. This was an extraordinary step toward the ending of slavery in America, but not the final step. For one thing, Lincoln issued his proclamation on the strength of his “war power” as commander-in-chief, in order to weaken the Confederacy’s powers of resistance. But there was no body of settled law concerning presidential “war powers” in 1863, and even Lincoln was anxious that federal courts might overturn both the proclamation and the freedom it legally awarded to three and a half million black slaves in the Confederacy. For another, the proclamation—precisely because it was a “war powers” document—could only be operative against slavery in the Confederacy; it did not wipe out slavery in the four states where slavery was legal, but which had remained loyal to the Union (Missouri, Maryland, Kentucky, Delaware).

President Abraham Lincoln had issued an Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, that declared “forever free” all the slaves in those parts of the breakaway Southern Confederacy not yet returned to Union control. This was an extraordinary step toward the ending of slavery in America, but not the final step.