Keanu Reeves as John Wick in John Wick: Chapter 4. Photograph by Murray Close. Courtesy of Lionsgate.

In our Spring issue, we published Kyra Wilder’s poem “John Wick Is So Tired.” To celebrate the poem and the recent release of John Wick: Chapter 4, we sent four reviewers to three different John Wick screenings over the course of a week.

Tuesday, March 21: Press Preview

The first thing we noted when we entered AMC Lincoln Square 13 for the New York press screening of John Wick: Chapter 4 was that film PR girls are way nicer than their fashion industry counterparts. Check-in was a breeze, and we were informed that since we had special blue wristbands, we didn’t have to turn in our phones. We hadn’t considered that we would potentially have to turn in our phones, but were relieved nevertheless. We were handed a very large stack of papers with a large John Wick logo at the top, containing detailed information about the franchise and a long explanation of the movie’s plot, which we chose not to read too closely for fear of spoilers. This heavy stack of papers was also where we first learned that the runtime was a whopping 169 minutes. This troubled us, mostly because we had had a lot of wine with dinner and were concerned that we would have to pee. The theater was packed with agitated-seeming nonjournalists who were somehow able to secure tickets. People wove up and down the aisles in a huff, frustrated by the first-come-first-served seating. A couple of women exchanged curse words over another woman’s volume. Multiple people arrived late with full take-out bags, their lack of discretion leading us to believe that the staff of the theater were not too concerned with enforcing the rules of this AMC John Wick press preview.

The French crime film maestro Jean-Pierre Melville once said, “What is friendship? It’s telephoning a friend at night to say, ‘Be a pal, get your gun, and come on over quickly.’ ” In the universe of John Wick, it’s pretty much that too, but it’s a thousand guns, two dozen archers, bows, arrows, knives, swords, bulletproof suits, a sundry list of exotic ammunition, an attack dog, a blind assassin, dueling pistols, a fleet of luxury attack vehicles, and a handful of classic American muscle cars. Oh, and if you could bring them all to the Sacré-Cœur, in Paris, by sunrise, that would be great, thanks.

By now, with the fourth installment in the franchise, the formula is familiar. John Wick (Keanu Reeves), on the run from the High Table (a governing body for the underworld whose main function just seems to be killing people) kills a lot of people in a series of highly choreographed set-piece action sequences in places like fancy hotels for assassins, fancy churches for assassins, and fancy Berlin techno clubs, also presumably for assassins. There’s something very charmingly mid-2010s about the environs and the soundtrack (was that the opening of Justice’s “Genesis”?), like a world where there was no COVID pandemic, but where everyone is a rich assassin in an ugly custom three-piece sparkly suit. Better times.

Reeves speaks softly and carries a number of big loud sticks, swords, et cetera, often breaking down his guns into their constituent parts and throwing them, stabbing people with them, or indulging in other creative but necessary acts of violence. There’s an extremely fetishistic aspect to the gearheaded breakdown of the guns, and to the clicking of magazine releases, that forms a sort of counterpoint to the theoretically balletic fight choreography. Like Jean-Pierre Melville, John Wick normally drives a classic Mustang. How a similar car made its way to Paris in this film is anyone’s guess. There really aren’t any other comparison points between this film and Melville’s Le Samouraï, except that they’re both about assassins. Oh, and friendship.

—Alex Tsebelis and Chloe Mackey

Thursday, March 23: Premiere Day

I was supposed to go to a cosplay premiere event for John Wick: Chapter 4, but couldn’t get tickets in time—so I ended up at a normal Regal theater for the nearly sold-out 7 P.M. screening. I’d dressed for cosplay that morning, but I’d also never seen a John Wick film, so I had to make some educated guesses. Action movies, I knew, are all about men in suits performing suit-inappropriate actions. Assuming John would have a sexy love interest (this turned out to be wrong), I selected the female suit equivalent, a secretary costume: fitted brown houndstooth minidress. I loitered at the Regal Essex Crossing second-floor bar, photographing my outfit against the sunset over the Williamsburg Bridge, a very John Wick backdrop. “Is this for a fashion blog?” the Regal bartender asked me, winking. “No,” I said. “I mean, yes.”

Everyone else in the audience wore joggers, a garment absent from the fashion-forward film. Indeed, without context, the opening sequence registered to me as a kind of psychedelically plotless Saint Laurent advertisement, a brand for which Keanu Reeves is an “ambassador.” We begin with John Wick punching a brick in an elaborately shadowy warehouse. His training is interrupted by the dramatic entrance of his three-piece suit, appearing, silhouetted against the inexplicably fiery glow of a doorway, in the hands of some sinister fellow (friend, foe, butler?). The suit—presented in a manner usually reserved for the hero’s weapon of choice—is accompanied by a line of dialogue I neither understood at the time nor remember now, but which was clearly a classic John Wick catchphrase that meant something like “Here’s your suit. Now it’s time to kill—again.” And he totally does.

Wick’s antagonist, the Marquis, sports a series of glittery waistcoats complete with asymmetrical gold buttons and stupid little chains. His weapon: blades. His goal: glory. The effete Marquis probably has ten times as much dialogue, and charisma, as John Wick, who is completely without character attributes. John Wick is just a killer, more like a machine than a human being. His suit, like his gun, is all-black.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

Tuesday, March 28

The statistically inclined among us might have told me, as my projectionist friend did later on, that the odds of the screen going black twenty minutes into my 10:30 A.M. Sunday-brunch screening of John Wick: Chapter 4 at the Alamo Drafthouse up at least three escalators in the City Point mall were actually not so low in the age of automated projection. So my associate (a different one) and I finished our cauliflower-crust breakfast pizza and got a refund, and I picked up where we’d left off two days later at AMC 34th Street 14, where Nicole Kidman’s on-screen avatar assured me that the display was IMAX and the projectors laser. In the basement of a Berlin techno club full of bad, identically robotic dancers making repetitive upward arm movements, John Wick is dealt in to a five-card-draw game of poker with the two hitmen contracted to murder him and a German High Table official named Killa. At the end of the game, Wick puts two black eights and two black aces on the table, in what is usually a strong move—called the dead man’s hand, as I learned that night on the Reddit forum r/NoStupidQuestions, after the hand Wild Bill Hickok was reputedly holding when he was shot—but Killa destroys his chances by playing an unbeatable five of a kind: impossible to achieve without cheating, of course, because there are only four suits in a deck. Vegas would do well to be reminded, though, of the words of the Marquis, which I should start telling myself when I wake up in the morning: “How you do anything is how you do everything.” The odds are always against John Wick, and he always wins anyway. In the end, he slices Killa’s neck open with a playing card, and pockets one of his gold teeth.

—Oriana Ullman, assistant editor

Photograph courtesy of Kyra Wilder.

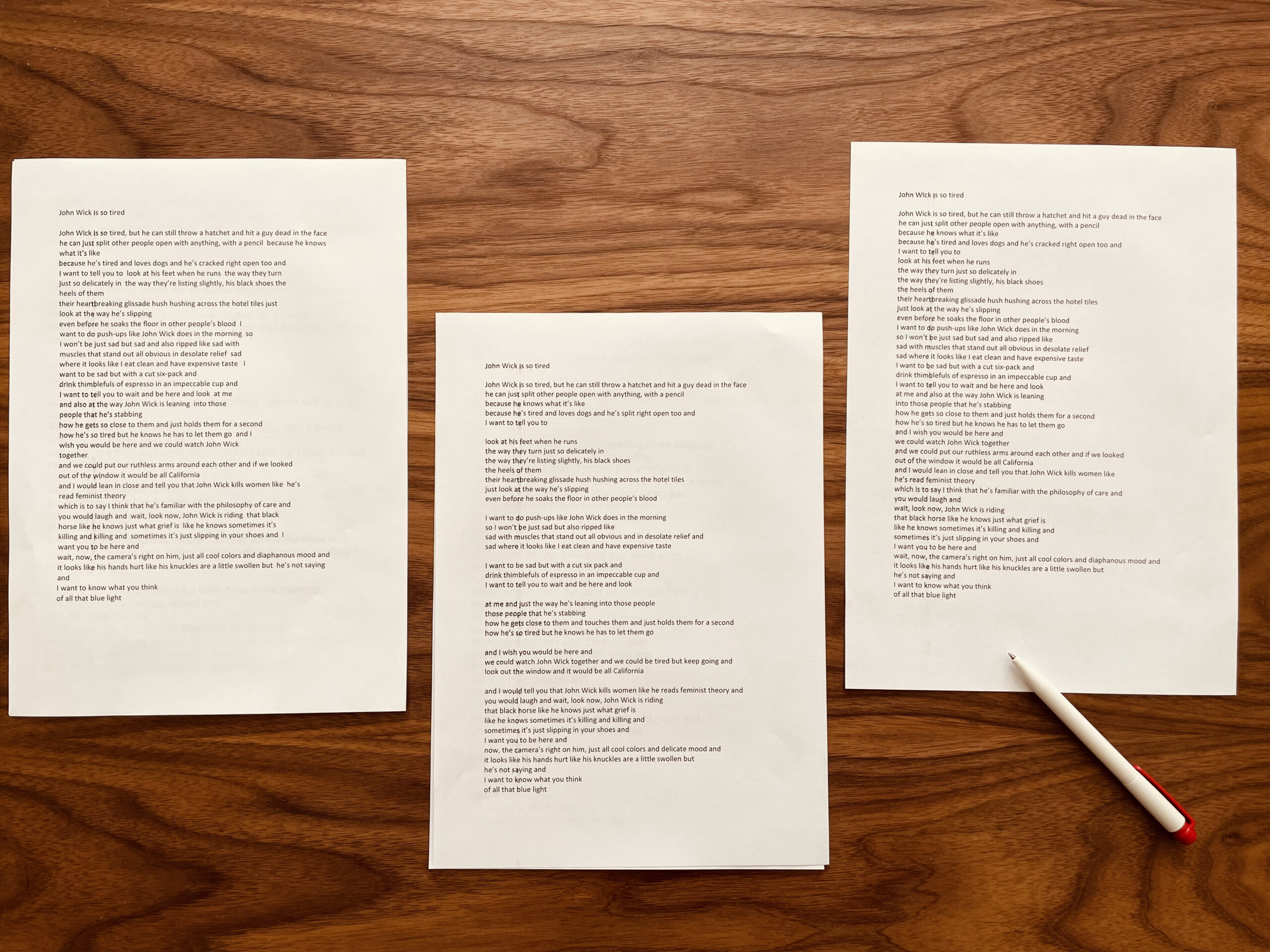

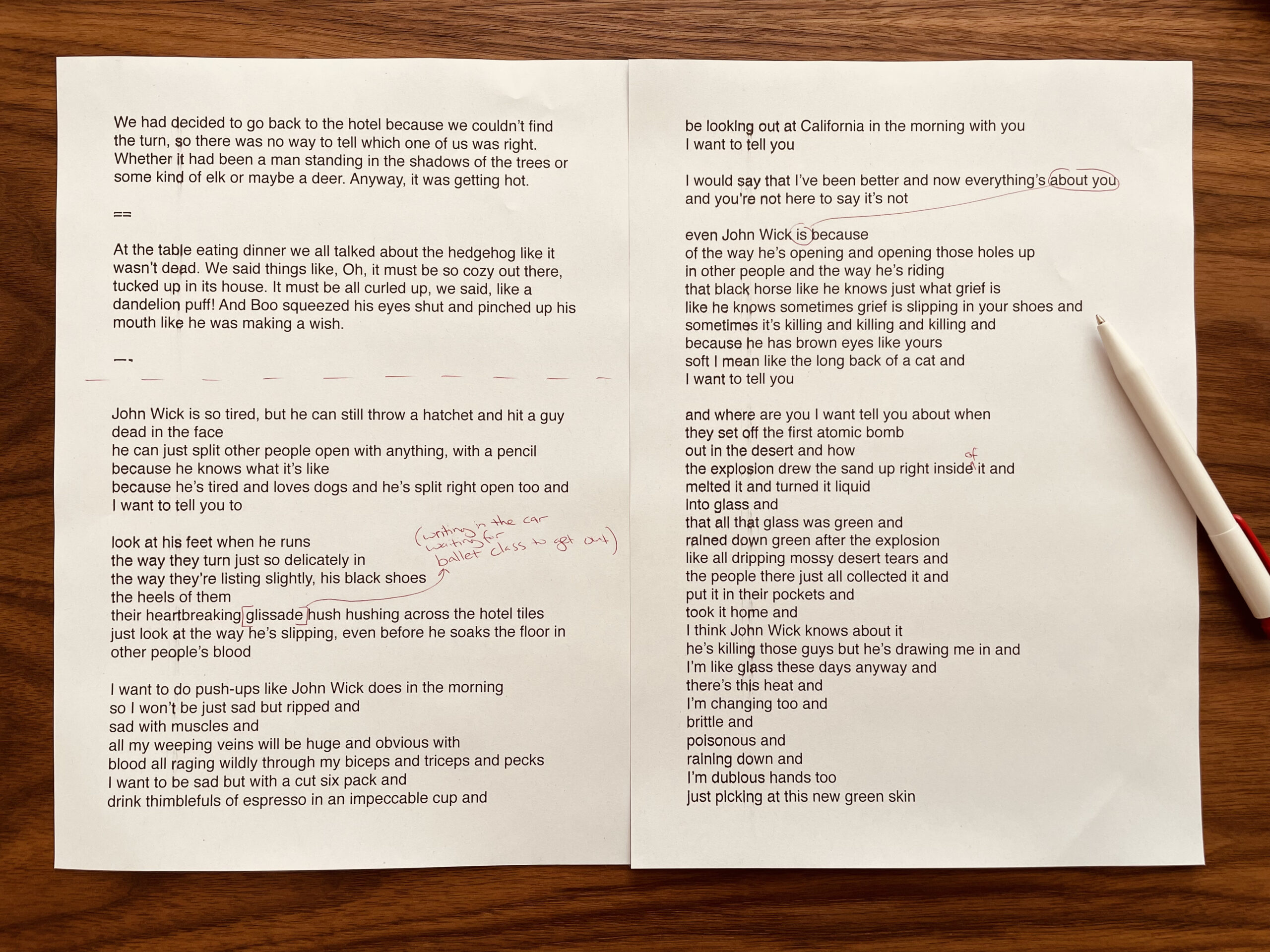

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Kyra Wilder’s “John Wick Is So Tired” appears in our new Spring issue, no. 243.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase?

With the first line. It was something I’d thought a lot about—I run marathons, and in those tense few days before the race, when I’m drinking water and carb loading and meditating on what’s going to happen, I watch John Wick, specifically because of the way Keanu Reeves runs. He looks so tired, but he’s winning.

In the fall of 2021, I was tapering for a marathon and then I had to go to a funeral, and suddenly my John Wick time got invaded by real grief. And John Wick was good for that, too.

What were you reading while you were writing the poem?

I was reading a lot of Ian Fleming that fall. I got pretty obsessed with the fact that he included a recipe for scrambled eggs in a James Bond story. In that story, Bond is completing some kind of mission in New York but also being really whiny about the poor quality of American eggs—to the point that he’s wandering around the city going into bodegas and criticizing them. So, it was either going to be “John Wick Is So Tired” or “James Bond Could Make You Some Pretty Good Eggs.”

Where did you write this poem?

That glissade is in there because I was writing in the car, waiting to pick up my daughter from ballet class. I write all over—sometimes even at my actual desk. I have a print from Bas Jan Ader’s I’m too sad to tell you on the wall. There’s nothing better to stare at when things are going badly.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or to friends or confidantes? If so, what did they say about them?

I showed it to my husband. He’s a math guy and doesn’t read poetry, but he’s usually right about my writing. When he read the first draft, he liked the first half but said he “didn’t get” the ending. Reading that draft again now, I see what he meant.

That version was maybe more like a novel or a short story. We’ve started with John Wick, but by the end we’re lost in the desert. It’s chatty, reaching for all the conversations that are being missed—the speaker wants to watch John Wick and tell the lost person historical asides about nuclear bomb testing sites. Of course they do, but that’s for a novel. In the context of a poem, it’s too much, too close together. I’m hitting the meaning-gong too many times. John Wick (the character, the movies, the Keanu) is so good, and the poem is about this one feeling of where-are-you-right-now-how-could-you-miss-this-one-particular-thing, so we need to stay with John Wick and forget the desert.

After I found an ending that felt more specific and focused and safely clear of novel/short story/essay territory, I sent a copy to my agent, Jon Curzon. He told me he’d once made an Instagram account called Keanu Leaves, which was just full of pictures of Keanu Reeves waving goodbye.

How else did the poem change over time?

I wrote it without stanzas at first, and then decided to break up the poem following the speaker’s thoughts—where the thinking shifted, or where I thought they might pause or take a breath. The stanzas got me closer to the person speaking—they helped me hear how the speaker would say the lines.

As useful as they were, though, the stanzas made the poem too dramatic. They looked like they were trying too hard. We’re starting with a hatchet thrown at someone’s face—we don’t need the additional histrionics of white space. Then it was all playing with line breaks. One of the drafts has two lines with single words. It’s not that I was thinking I might eventually end up with one-word lines—it was that I was breaking the lines up everywhere and leaving them for a while to see how they looked. I was just pushing things around, moving lines back and forth and reading it again every few days. I would open the document, break up lines, and leave it for a bit.

Once I got the poem to the point where, when I looked at it fresh, there wasn’t anything I wanted to change, I sent it off and left it for dead.

Kusudama cherry blossom. Courtesy of praaeew, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

As I get older, and the world gets worse, or gets differently bad, or stays the same but my understanding of its badness deepens and broadens, I grow ever more dependent upon books like Akwugo Emejulu’s Fugitive Feminism. This short, sharp text reminds readers that, like the rattling door in a haunted house or the concerned face of a friend who understands well the way a lover is slowly bringing about your annihilation, it is good to leave that which does not serve you. Fleeing, as in the case of the enslaved from the plantation, is no act of cowardice but a tremendous gesture toward liberation.

The flight Emejulu encourages is not from a place but from a conceptual space. Referencing the work of Black critical theorists like Sylvia Wynter, Fugitive Feminism troubles the notion of the “human,” arguing that it is not a neutral, objective term for one type of mammal but a philosophical and political category informed by colonialism that, from its invention, excluded Blackness and Black people. For years, many have fought (to no avail) to be, for once, called and acted upon as humans, but for Emejulu, there is nothing to be reclaimed in that cursed white supremacist taxonomy. When we stop seeking inclusion into a category built on genocide and eugenics, there is freedom to explore other ways of being, seeing, and doing.

Emejulu’s writing is clear, evocative, and concise, and while readers with no background in the subject material may find places where they need to spend more time, Fugitive Feminism is an extraordinarily accessible text that will touch many of those left behind by society without sacrificing complexity and critical rigor.

—Rivers Solomon, author of “This Is Everything There Will Ever Be”

A few Januaries ago, I spent a week in Sheringham, a coastal town in Norfolk, England. The friend who’d invited me said that in the summer, the town swells by thousands as pleasure-seekers descend. In the winter, it is cold, rainy, pleasantly desolate. Perfect for writing, which is what we were there for. I’d decided to use the time to write a short story, something I hadn’t done since childhood.

When I don’t know how to do something, I research, so I’d been reading many short stories, new and not so new, by Emma Cline, Shirley Hazzard, Gina Berriault, Deborah Eisenberg, Lucia Berlin, Grace Paley, Tillie Olsen, and Yiyun Li. For that week, I brought with me Sylvia Townsend Warner’s selected stories. On the train from London, I read “Oxenhope,” first published in 1966. I’d read it before and liked it. This time it settled on me like an atmosphere. As did Sheringham, when I arrived, with its crash of waves against the seawall on nighttime walks, its empty arcades, and its signs advertising candy floss. Before we arrived, a cliff had crumbled into the sea, taking with it a holiday cottage. (We had to imagine the collapse; we could see only land’s unspectacular absence.)

In “Oxenhope,” a sixty-four-year-old man named William returns to the rural Scottish village where he spent a transformative month at seventeen, when, overstudied and exhausted, he’d suffered what he calls a “brain-mauling.” He’d been on a disastrous walking tour when a family of farmers saved him from a storm and insisted he stay. The dailiness of Oxenhope restored him. After departing, he’d undertaken the life he was supposed to have: university, good career, marriage, et cetera. Decades later, though, he feels “like a castaway on the remainder of what life was left to him.” So he returns to Oxenhope. Townsend Warner captures the intricacies of coming back to a place that once changed you, carrying with you all the changes that have happened since. Such a return forces the resisted, unavoidable concession “that the past was draining away out of the present, that Oxenhope, lovely as ever, was irrecoverable … He had grasped at the substance, and the lovely shadow was lost.” As he leaves Oxenhope for the second time, the past unexpectedly comes charging into the present: a young boy shares a bit of local lore, not knowing that the tale features the teenage William. Being a story, having “tenancy in legend,” consoles him. Narrative redeems the fact that the past is uninhabitable.

The story I wrote that week in Sheringham—which appears in the Review‘s Spring issue—does not resemble “Oxenhope,” except, perhaps, in its attention to what is said and what it’s possible to say, and to the force that narrative exerts on the future, not just on the past.

—Elisa Gonzalez, author of “Sanctuary”

Recently I watched Klostės (Folds/Pleats), a black-and-white stop-motion art film directed by the Irish artist Aideen Barry and based on the stories and myths of Kaunas, Lithuania. The film brings together hundreds of local writers, dancers, musicians, and artists in an ambitious collaboration that explores the histories of the city and its interwar architecture. Barry, influenced by her early exposure to Russian, Czech, and Lithuanian stop-motion film on eighties Irish television, revels in the surreal. From the opening shot, a kaleidoscope of abstract, origamiesque pleats of black paper, the film masterfully folds stories upon stories into a dizzying, nonverbal world where colorful characters and the architecture of the city collide. A woman walks into a restaurant; shortly after she orders from the menu, a cake assembles itself in the shape of a building, right by her table. From there we are swept into the magic of Kaunas. In Klostės, Barry suggests that we can reimagine a postcapitalist world, and the citizen as artist in it.

—Elaine Feeney, author of “Same, Same”