Guest post by Sabine Carey, Marcela Ibáñez, and Eline Drury Løvlien

On April 10, 1998, various political parties in Northern Ireland, Great Britain, and the Republic of Ireland signed a peace deal ending decades of violent conflict. Twenty-five years later, the Good Friday Agreement remains an example of complex but successful peace negotiations that ended the conflict era known as The Troubles.

Since the agreement, Northern Ireland has experienced a sharp decline in violence. But sectarian divisions continue as a constant feature in everyday life. Peace walls remain in many cities, separating predominantly Catholic nationalists from predominantly Protestant unionist and loyalist neighborhoods. Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol increased tensions between the previously warring communities, leading to an upsurge in sectarian violence, which has been a great cause of concern.

In March 2022, we conducted an online survey to understand attitudes toward sectarianism among Northern Ireland’s adult population. Our results show that sectarianism continues to impact perceptions and attitudes in Northern Ireland. The continued presence of paramilitaries is still a divisive issue that follows not just sectarian lines but also has a strong gender component.

Our findings show that the pattern of who identifies as Unionist or Nationalist closely resembles the patterns of who reports having a Protestant or Catholic background. Unionists prefer a closer political union with Great Britain and are predominantly Protestant, Nationalists are overwhelmingly Catholic and are in favor of joining the Republic of Ireland.

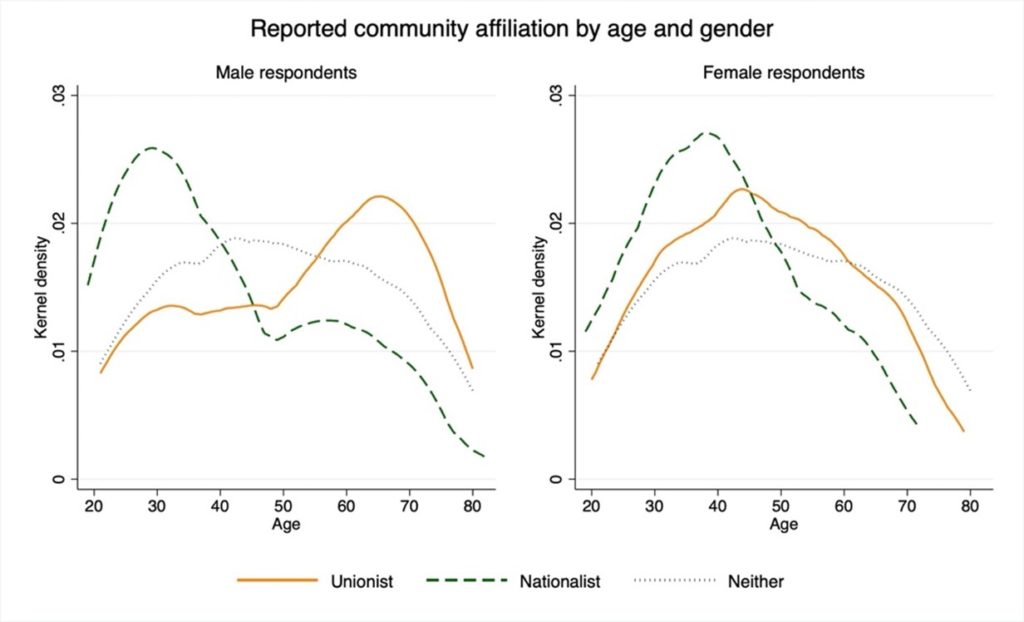

Catholic and Nationalist identities appear to have a greater salience for the post-agreement generations than for older generations who lived through the Troubles. For Protestant and Unionist respondents, the opposite is the case, as religious background and community affiliation have a higher salience among older groups, particularly among men. Among the adults we surveyed, for men the modal age of those identifying as Unionists is 58 years, for women it is 46.

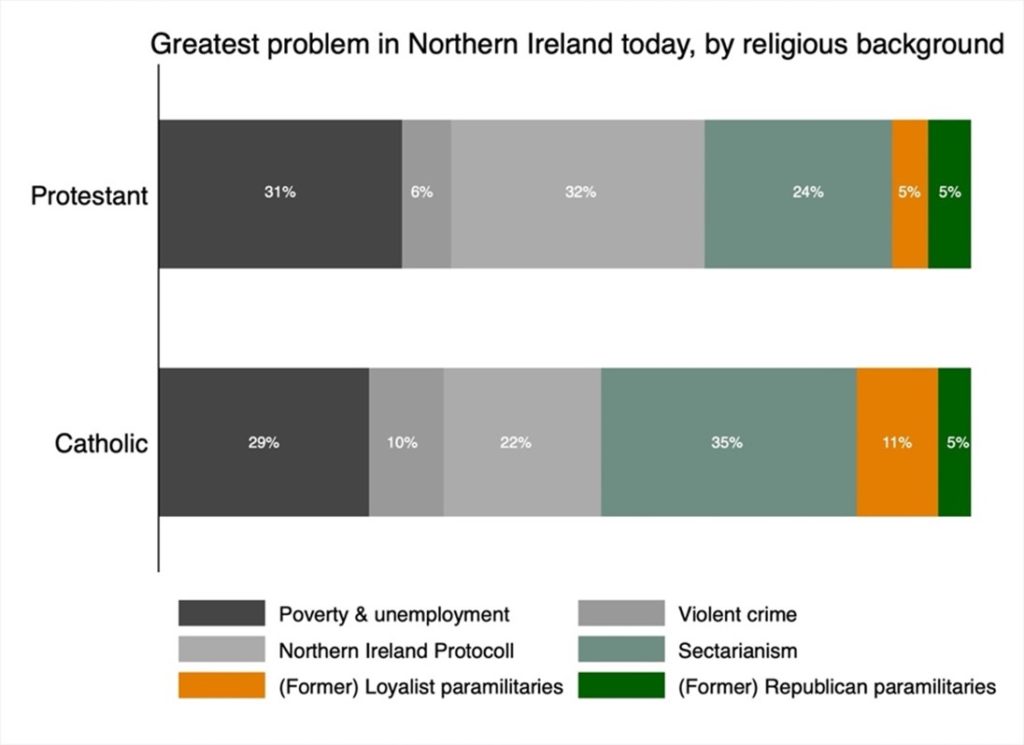

When asked about the greatest problem facing Northern Ireland today, sectarianism still features strongly among both communities. Today, the fault lines of the conflict seem to resonate more with those from a Catholic background than with those from a Protestant background. While Protestants were predominantly concerned with poverty and crime, among Catholics sectarianism emerged most often as the greatest concern. Just over 50 percent of Catholic respondents mentioned an aspect relating to the Troubles (sectarianism or paramilitaries) as the greatest problem today, compared to only 39 percent of Protestant respondents. Most Protestant respondents selected Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol as the greatest problem, reflecting concerns of the Protestant community discussed in a Political Violence At A Glance post from 2021.

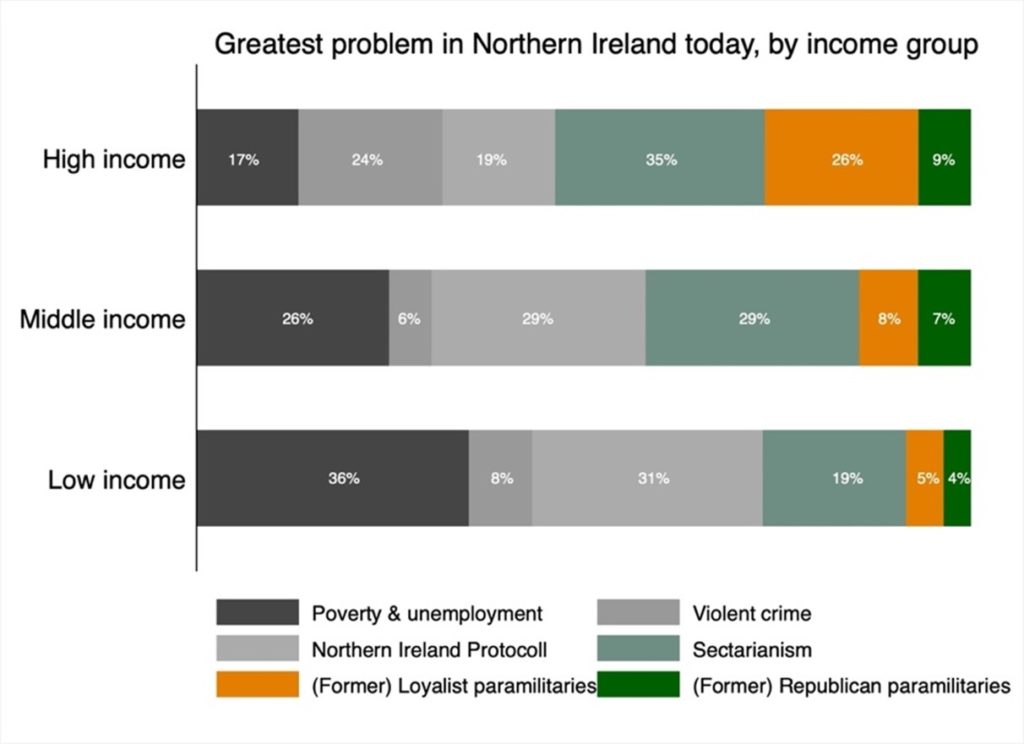

To what extent does economic status drive concerns? Those who see themselves as belonging to a lower-income group were more likely to identify poverty and unemployment as the greatest problem. Concerns about sectarianism and (former) paramilitary groups appeared most prevalent among those who placed themselves in the high-income group.

The continued presence of Loyalist and Republican paramilitaries is a noticeable feature in post-conflict Northern Ireland. While they are predominantly associated with violence and crime, some view them as a source of security and stability. While our findings show that concerns about paramilitaries were more prevalent among high-income earners, the perception of paramilitaries has a significant gender component. Nearly 50 percent of male Catholic respondents attributed a controlling influence to paramilitaries in their area. And while most of them saw these groups as a source of fear and intimidation, 32 percent agreed that the paramilitaries kept their local area safe. But only 5 percent of female Catholic respondents felt similarly. This difference is not as stark between female and male Protestant respondents. Both groups were substantially less likely than male Catholics to consider paramilitary groups as a source of safety.

Different perceptions of armed groups by gender are not unique to Northern Ireland. A 2014 study on Colombia found significant differences between female and male perceptions of post-conflict politics and participation. Although there were no substantial gender differences in the overall support for the peace process in Colombia, female respondents reported higher levels of distrust and skepticism toward demobilization, forgiveness, and reconciliation and higher disapproval of the political participation of former FARC members. The effect was even greater for mothers and women victimized during the conflict.

Violent attacks have dampened the anniversary celebration of the peace agreement and 25 years of relative stability. The recent injury of a police detective by an IRA splinter group, reports of paramilitary-style attacks and the use of petrol bombs against the police, coupled with turf battles between Ulster factions are continuous reminders of the presence and power that paramilitary organizations still hold across Northern Ireland. Even today, communities are kept under siege through violence and ransom. The formal termination of violent conflicts through peace agreements, as in the case of the Good Friday Agreement and other prominent examples such as the 2016 Colombian Peace Accord, does not automatically imply the disbandment of armed organizations. The impact of the presence of (former) armed groups in people’s daily lives continues to be high in most post-conflict contexts.

Findings from surveys in other post-conflict environments mirror this long shadow of war. A study of Croat and Serbian youths showed the continued impact of the Yugoslav Wars on ethnic group identities and how continued communal segregation impacts inter-group ethnic attitudes towards out-groups. A recent study finds that a decade after the civil war in Sri Lanka people from previously warring sides have very different views of peace and security. Respondents who belong to the defeated minority ethnic group, the Tamils, provided a more negative assessment of security and ethnic relations than those from the victorious majority, the Sinhalese. They also reported seeing irregular armed groups in a more protective role rather than a threatening one, when they encountered them, as we show here. And in many post-war countries, it’s the police who threaten peace, as discussed in this post. A study on Liberia found that experiences during the war continued to impact perceptions of the police afterwards. Victims of rebel violence were later more trusting of the police, while victims of state-perpetrated violence were not.

Much research is rightly concerned about how to avoid the conflict trap. Yet even countries that avoid falling back into full-scale civil war oftentimes do not offer adequate security and peace for all groups of their civilian population. Continued vigilance of unequal experiences and perceptions of security are necessary to work towards meaningful and lasting peace.

Sabine C. Carey is Professor of Political Science at University of Mannheim. Marcela Ibáñez is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Chair of Political Economy and Development at the University of Zurich. Eline Drury Løvlien is Associate Professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of Teacher Education.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) via the Collaborative Research Center 884 “Political Economy of Reforms” at the University of Mannheim.

It is a mistake to ignore the connection between the attempted judicial coup in Israel and the occupation of the West Bank.

From The Daily Mail:

— Read the restDemonstrators are said to have thrown crabs at police following a week of violent clashes over France's reforms to the national pension age.

A stand-off over maritime regulations in Rennes saw protesters clutching spider crabs during altercations with the authorities.

Individual protests, like those in Hong Kong, may be defeated. But the global protest movement is only beginning.

The post Protesters of the World, Unite appeared first on Public Books.

Private investigator hired to look into possible involvement of two student activists in occupation of building

Sheffield University has been criticised for hiring a private investigator to look into the possible involvement of two student activists in a protest in one of its buildings.

The two students received letters on 9 November informing them that the university had hired Intersol Global, a firm of investigators, to look into whether they were involved in a student occupation of a building in late October protesting against Sheffield’s links to the arms industry.

Continue reading...Guest post by Killian Clarke

Counterrevolutions have historically received much less attention than revolutions, but the last decade has shown that counterrevolutions remain a powerful—and insidious—force in the world.

In 2013, Egypt’s revolutionary experiment was cut short by a popular counterrevolutionary coup, which elevated General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to the presidency. In neighboring Sudan, a democratic revolution that had swept aside incumbent autocrat Omar al-Bashir in 2019 was similarly rolled back by a military counterrevolution in October 2021. Only three months later, soldiers in Burkina Faso ousted the civilian president Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, who had been elected following the 2014 Burkinabè uprising.

These counterrevolutions all have something in common: they all occurred in the aftermath of unarmed revolutions, in which masses of ordinary citizens used largely nonviolent tactics like protests, marches, and strikes to force a dictator from power. These similarities, it turns out, are telling.

In a recent article, I show that counterrevolutionary restorations—the return of the old regime following a successful revolution—are much more likely following unarmed revolutions than those involving armed guerilla war. Indeed, the vast majority of successful counterrevolutions in the 20th and 21st centuries have occurred following democratic uprisings like Egypt’s, Sudan’s, and Burkina Faso’s.

Why are these unarmed revolutions so vulnerable? After all, violent armed revolutions are usually deeply threatening to old regime interests, giving counterrevolutionaries plenty of motivation to try to claw back power. There are at least two possible explanations.

The first is that, even though counterrevolutionaries may be desperate to return, violent revolutions usually destroy their capacity to do so. They grind down their armies through prolonged guerilla war, whereas unarmed revolutions leave these armies largely unscathed. In the three cases above, there was minimal security reform following the ousting of the incumbent, forcing civilian revolutionaries to rule in the shadow of a powerful old regime military establishment.

A second explanation focuses on the coercive resources available to revolutionaries. During revolutions waged through insurgency or guerilla war, challengers build up powerful revolutionary armies, like Fidel Castro’s Rebel Army in Cuba or Mao’s Red Army in China. When these revolutionaries seize power, their armies serve as strong bulwarks against counterrevolutionary attacks. The Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba is a good example: even though that campaign had the backing of the CIA, it quickly ran aground in the face of Castro’s well-fortified revolutionary defenses. In contrast, unarmed revolutionaries rarely build up these types of coercive organizations, leaving them with little means to fend off counterrevolutions.

After looking at the data, I found that the second explanation has more weight than the first one. I break counterrevolution down into two parts— whether a counterrevolution is launched, and then whether it succeeds—and find that armed revolutions significantly lower the likelihood of counterrevolutionary success, but not counterrevolutionary challenges. In other words, reactionaries are just as likely to attempt a restoration following both armed and unarmed revolutions. But they are far less likely to succeed against the armed revolutions, whose loyal cadres can be reliably called up to defend the revolution’s gains.

Unarmed revolutions are increasing around the world, especially in regions like Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa. At the same time, violent revolutions are declining in frequency, particularly those involving long, grueling campaigns that seek transformational impacts on state and society, what some call social revolutions. In one sense, these should be welcome trends, since unarmed revolutions result in far less destruction and have a record of producing more liberal orders. But given their susceptibility to reversal, should we be concerned that we are actually at the threshold of a new era of counterrevolution?

There are certainly reasons for worry. Counterrevolutions are rare events (by my count, there have only been about 25 since 1900), and the fact that there have been so many in recent years does not augur well. Counterrevolutionaries’ prospects have also been bolstered by changes in the international system, with rising powers like Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates acting as enthusiastic champions of counterrevolution, particularly against democratic revolutions in their near-abroads. Today’s unarmed revolutions, already facing uphill battles in establishing their rule, with fractious coalitions and a lack of coercive resources, must now also contend with counterrevolutionary forces drawing support from a muscular set of foreign allies.

But though they may struggle to consolidate their gains, unarmed revolutions have a record of establishing more open and democratic regimes than armed ones do. Violent revolutions too often simply replace one form of tyranny with another. The question, then, is how to bolster these fledgling revolutionary democracies and help them to fend off the shadowy forces of counterrevolution.

International support can be crucial. Strong backing from the international community can deter counterrevolutionaries and help new regimes fend off threats. Ultimately, though, much comes down to the actions of revolutionaries themselves—and whether they can keep their coalitions rallied behind the revolutionary cause. Where they can, they are typically able to defeat even powerful counterrevolutions, by relying on the very same tactics of people power and mass protest that brought them success during the revolution itself.

Killian Clarke is an assistant professor at Georgetown University.

Guest post by Kevin Gatter

On the night of October 30, 1995, Canadians held their collective breath as the votes in Quebec’s independence referendum were counted. In the end, the pro-independence camp lost the referendum by a figurative eyelash: 49.42 percent of voters supported independence, while 50.58 percent voted to remain part of Canada. Quebec’s political status continued to be a delicate issue in the years following the referendum.

In March 2022, I was in Quebec City, a hotbed of Québécois nationalism in the 1990s. But apart from the omnipresent blue-and-white Fleurdelisé (flag of Quebec), I saw little evidence that this had been the center of a passionate pro-independence movement just a few decades prior. On the train to Montreal, I asked my seatmate, a student in their 20s, about Quebec independence. The response was a confused “Quoi?” and then a timid, “Oh, that’s not really a thing anymore.”

The case of Quebec illustrates a challenge facing many secessionist movements, which seek to detach a region from a country and make a new country out of that region. These movements often ebb and flow: they go through periods where they are more active and others where they recede into the background. The secessionist movements in the headlines have varied quite a bit over the past few decades: it was the Basques in the 1980s, Quebec in the 1990s, and Scotland in the 2010s.

Some of these movements are currently on the downswing, like in Quebec. The Parti Québécois—the main party advocating independence—currently holds 3 out of 125 seats in Quebec’s National Assembly. In Catalonia, a region in eastern Spain, the independence movement has held massive rallies since 2010. But while the pro-independence Estelada flag is still a common sight on the balconies of Barcelona, opinion polls have shown a decline in support for independence since 2018.

In other regions, secessionist movements are gaining momentum. The pro-independence Scottish National Party has had the majority in Scotland’s parliament since 2011. Since 2014, when 45 percent of voters backed independence in a referendum, support for independence has climbed to 54 percent. And in nearby Wales, 10,000 people marched in Cardiff in support of independence in October 2022.

Why do these movements go through periods of higher and lower activity? There are a variety of reasons that can account for these swings. Sometimes a violent government response to calls for secession intimidates would-be supporters. In Catalonia, the Spanish government’s jailing of pro-independence leaders and violence against participants in the 2017 referendum created a sense of apprehension. Catalan nationalist organizations have since complained of government surveillance and harassment. In other cases, would-be supporters feel they have received satisfactory concessions. In Quebec, the younger generation has come of age in a time in which French speakers can manage companies, there are laws strengthening the public use of French, and immigrants are required to enroll their children in French-speaking schools. The French language in Quebec is in a more secure position than it was a few decades ago, alleviating a major concern of independence supporters.

But government actions can also fuel secessionism. The Brexit vote played a major role in strengthening the independence movement in Scotland and, to a lesser degree, in Wales. Many people in both regions believe that independence would allow them to rejoin the EU. For many people in Scotland in particular, the Brexit vote was taken as evidence of the difference in values between Scotland and the rest of the UK. Recently, the UK government has indicated that it will block Scotland’s Gender Recognition Reform Bill, further contributing to the deadlock between Scotland and Westminster.

Even the COVID-19 pandemic has played a role in secessionism. In Wales and Scotland, there is a sense that the governments of these regions handled the pandemic better than the UK government in London did. This has given people a sense of confidence in the ability of the Scottish and Welsh to manage their own affairs, leading to a reevaluation of these regions’ ability to govern themselves as independent nations.

It is hard to predict what the future will hold for secessionist movements. Movements that seem unstoppable at one point can suddenly go stagnant, as in Quebec. Independence might have the upper hand in Scotland, but the movement risks becoming divided over disagreements on how to react to the UK government’s refusal to sanction a second independence referendum. In Wales, traditionally anything but a hotbed of secessionist activity, support for independence is rapidly growing. As we continue to grapple with a pandemic, the war in Ukraine, challenges to democracy around the world, and the climate crisis, we will have to see how secessionist movements adapt to these new realities.

Kevin Gatter is a Ph.D. candidate at UC Los Angeles’ Department of Political Science. He is also a dissertation fellow at the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation.

Don’t have time to read the article? Listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

This story was funded by our members. Join Longreads and help us to support more writers.

Christy Tending | Longreads | February 2, 2023 | 14 minutes (3,768 words)

There are things that able me. A chair. One person speaking to me at a time. Shoes that are not cute, but spare me nerve pain. A hot bath with epsom salts: so hot it would scald most, but my skin is like Kevlar. It craves the heat and wishes for it to dig deeper. These are simple but necessary things that make my life more livable.

They do not “enable,” marking conspiracy in a habit I am trying to quit; I am not done yet with my propensity for being alive in the world and I’m not ashamed of what these things offer. They able me. They render me capable of basic participation in my life in its myriad and fantastical forms: watching my child play soccer; eating dinner with my family; browsing through my favorite bookstore; coordinating a protest; hiking with my friends.

These accommodations — and others I require but have not named — are not merely comfortable, but necessary, an antidote to the ways the world, as it is, dis-ables me. The way the world tries to tell me that simple pleasures do not belong to me. Due to the burdensome inefficiencies of my body, I deserve exclusion.

When I train activists in street protests and direct action, which is my avocation in this lifetime, one of my rules is “One Diva, One Mic,” which is to say, “Please shut the fuck up when someone else is talking because my brain cannot process multiple sounds at once.” I talk about how a motorized scooter can make for an excellent blockade tool. Disability is not the same as vulnerability; I have been deemed broken, but am not fragile. And when I raise my voice in service of my needs, I am teaching others to do the same. When we meet our needs together, we are building the world we want to live in.

Disability is not the same as vulnerability; I have been deemed broken, but am not fragile. And when I raise my voice in service of my needs, I am teaching others to do the same. When we meet our needs together, we are building the world we want to live in.

Translation and interpretation take many forms. Sometimes, to make someone able and free to participate is simply to speak in a language they can understand. Sometimes, when my husband and son are both talking to me at the same time, I put up both hands and say, “Chotto matte, kudasai,” which means, “Please wait a moment” in Japanese (which means I am serious; when the white person starts snapping at them in Japanese, they know it’s serious). Auditory overwhelm means I need quiet and accommodation from my own family.

My son brings me a pillow for my back, and then climbs into my lap. I am cushioned and I am cushion. This is how care happens.

If my life were a cheesy ’80s movie, it would open in freeze frame: me, lying on a field, trapped underneath a pony who crashed to the ground with me as his only buffer; my exasperated voiceover saying, “You may be wondering how I got here.” I was 12, about to enter the seventh grade.

Kickstart your weekend by getting the week’s best reads, hand-picked and introduced by Longreads editors, delivered to your inbox every Friday morning.

In the film (as it was in life), the pony stands up on my left femur, righting itself. I have a concussion and a broken nose and a horseshoe print on my thigh. I am taken, in cervical collar, away in an ambulance. The horseshoe bruise is so thick I can’t fully zip up my chaps for a couple of weeks. The film speeds up, hurtling me through time. I cannot tell you when the pain began, but underneath the pony is a good time to start.

At 12, I did not have the context or the language to understand what I was becoming or, more specifically, what was becoming of me. It took years, decades of working with and through disability justice frameworks to fully give myself over to incorporating disability as a part of my identity and to understand how disability colors my life and my self-perception.

When I did, it became easy to catalog: scoliosis, clinical depression, complex post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety, chronic headaches, auditory processing issues, ADHD. This is not exhaustive, but the rough sketch of things. This list does not account for my humanity — the person experiencing all of this — only how I am failing to measure up to the demands of capitalism. People want to know, without putting it quite this way, how I am compensating for these shortcomings. They very nearly ask for an apology that is not coming.

More than once, someone has told me they couldn’t “live like that.”

I have finally gained the fluency I needed to recognize and appreciate and celebrate myself as disabled. I do not embrace the term for having accomplished or overcome anything, and not as a signal of defeat (although there are plenty of people who love to see it that way), and certainly not as a beacon of “inspiration,” but as a loving gesture toward myself. To see myself as disabled is the entrypoint to access what some call self-care, but I call compassion.

Disability is not a sign of failure to care properly for myself, but as the beginning of meeting myself with the tenderness I require to move through the world. It is still a radical statement to meet your own needs without prerequisite, without means-testing your efficiency under capitalism. Acknowledging myself as disabled means I can then work to subvert the forces disabling me. Which begins with my worth and what goodness means. When I tell people, “I’m disabled,” they cock their heads to one side and frown. “Don’t say that,” they respond, bottom lip plump. I know I am supposed to comfort them, to take it all back, to smooth things over. Disability shames us both: the witness and the showgirl. Their embarrassment tells me I have subverted the unspoken contract. I do not want to soothe them; I am worth knowing myself.

At 12, all I knew was that other kids my age did not talk about pain in the way I did. Pain did not interfere with their experience of being 12. The other kids seemed limitless. I felt limitless in other ways: to ride bareback through the streams and ponds and fields and forests and hills of Maryland, without adult supervision, is the closest thing to pure, uncut freedom I can imagine for a middle-schooler.

The hardest thing is standing still. There is something about being upright, stuck in place, that is agony for my spine, my hips, my feet, my knees. Any arch support will ultimately fail if I am forced to be in one place without a chair for long. It feels like my brain is melting. I cannot form sentences and my peripheral vision grows dark.

Which is not to say in horseback riding I was immune to injury or consequence, but for a time, I was exempt from the force of gravity on my joints. I could find freedom in my partner. Together, we could fly. Part of freedom was the knowledge that our problems were ours to own, to fix or fumble.

In hindsight, it is difficult to untangle, like a well-plied yarn, what was chronic injury and what was the insidious beginning of chronic pain. When I was recovering from multiple concussions from horseback riding, I assumed if I simply stopped injuring myself, I would stop hurting. People would jokingly say, “Wait until you get to be my age!” As though pain is the exclusive domain of those over 40. As though I could not know agony at 12 or 14 or 16. I could. I thought, I am, right now. This kind of gaslighting is obviously harmful, when you say it out loud. Our society is so skilled at telling children not to trust themselves: to ignore their bodies’ signals, to focus on a body’s aesthetics, and to only value its abilities.

When my son says he is finished with dinner, I tell him the same thing each time: Thank you for listening to your body, no matter whether he’s had a fourth helping or eaten three bites. The quantity of food he consumes is not a goal in itself. I don’t care if he didn’t want to try the new thing I offered. What could be less my business than what another person eats?

***

Pain exhausts my mind. Stress and anxiety and depression exacerbate the pain. My disability keeps me so busy that I meet myself coming and going, like in the Dunkin’ Donuts commercial. It is both time to make the donuts; and I have already made the donuts.

What counts as disabled? (This is the same question I have been asking about my queerness since I knew enough shame to wonder: What is enough to count? To be worthy of being seen? To be real in the world?) I couldn’t tell you the answer, nor am I interested in policing anyone else’s experience of disability. I don’t really care anymore, if I’m honest, because I cannot know by looking at someone, and neither can you. What I do know is inquiry and identity give us access: to ourselves, to language, and finally to the accommodations that might actually grant us access. Identifying as disabled means I stand a chance of getting what I need. Much the way my pain is not static, being disabled is not a fixed position, necessarily. What if our needs were met? What if our unique way of being was honored?

I have never felt like enough. Not queer enough or disabled enough or mentally ill enough or enough like a mother, to qualify. It is not my reluctance, but my fear of taking someone else’s place, someone truly worthy. Someone who is enough. It is not internalized ableism, but my fear of claiming who I am as someone else decides I am a fraud; a heartbreak beyond words. There is stigma, of course. If I claim my disability, will it be turned against me? Like the boy in fifth grade, years after I knew I liked girls but years before I claimed a queer identity, who called me a dyke as though that’s a bad thing. I avoided getting sober for years because I wasn’t enough of a drunk; I hadn’t properly suffered.

I never reached the bottom. Or maybe there is no bottom — not really. At 40, I know who I am. Disabled, queer, mad as hell. Sober.

At 40, I know who I am. Disabled, queer, mad as hell. Sober.

When I was still riding, I was often asked to ride other people’s horses and, for lack of a better phrase, “Show them who was boss.” My father’s horse was an enormous black Trakehner, an East Prussian warmblood who did not always do what my father asked of him. So sometimes I, at 16 weighing 100 pounds, would hop aboard. Patrick would turn his head toward me, I would pet his nose, and then we would fly. Patrick would do whatever I asked. He was capable and athletic, and he knew despite my tiny size, I wasn’t going to take no for an answer. He also knew I wouldn’t ask him for anything he couldn’t do. I couldn’t muscle my way into making horses do what I wanted, but they learned to trust me all the same. I had a pony once who loved me so much he would come running across the field at the sound of my voice. I didn’t need to use a halter and lead-shank: He would heel like an overgrown golden retriever, eager to please. He would follow me to the barn, with his enormous head against my hip. He’d stand and rub his face against my rib cage as I tacked him up.

This is all to say my riding skill didn’t rest on authoritarianism or brute force. It was my intuition, compassion, and trust. It was a mutual effort. Horses, like most prey animals, can be tightly wound. My senses also had a hair trigger. One false move, and the muscles around my spine would spasm. Together, we could process an overwhelming amount of sensory input and turn it into something graceful and harmonious. In the face of the pain of daily life, this was my solace: working in tandem with another being, often just as terrified by the threat of disaster as I was.

Show-jumping has a steady rhythm: short outside lines, long diagonals. There are flower-boxes and soft dirt, birds in the rafters, a cool breeze, and an early sunset when you’re showing in October. Heels down, hands soft. Sometimes, you can walk the course with big strides, marking your lead change with a heel: a little hop to ease you around the corners.

I could read the subtle energy in my body more easily than my peers who hadn’t had to wonder why they woke up with neuropathy in their shoulder or why their spines sounded like breakfast cereal when they bent over. But those neural pathways also gave me information: Dig your heels in here, lift your hips now — and when I did, my pony would sail over the jump, lifting us both. Riding doled out injury and served as a balm for my more ordinary chronic pain.

My body gave its lessons early. This is not forever. For better or worse, this will not last.

We’ve published hundreds of original stories, all funded by you — including personal essays, reported features, and reading lists.

When I say I am disabled, this is what I mean: I am tired of not getting my needs met. I am tired of basic human needs being an afterthought. If I am “giving up,” the only thing I am truly sacrificing is the illusion of exceptionalism and individualism that got me into this mess in the first place. I am burning down the myth of self-sufficiency — or the idea that self-sufficiency should be a goal unto itself. I am surrendering the idea that I am a burden for having needs. I am demanding to be a part of the team and to be honored for what I bring to it.

It is expensive and time-consuming to be disabled. While I am not afraid to have my needs met, it is exhausting to have to advocate for myself every waking minute. It takes so much more time and energy and support to get what I need. It takes thought and preparation and resources to move through the world. Being disabled is also tremendously boring: Sometimes the days stretch out into weeks or months when I wish I were doing something besides my healing slog. I know the words will be back; I know one day my body will endure sitting at a desk again. Or maybe it won’t, and I will ponder that when it comes. There is no way to account for how I spend my days during those phases of necessary interiority.

For years, the person-first identity was pervasive. “People with disabilities,” they would say. But my disability is not luggage, separate from myself. And there is a kernel of truth inside me: Had the values of capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism not crept so pervasively into our collective consciousness, I would not have been rendered disabled in the same way. If we, collectively, engaged in mutual aid in more than fits and starts, then perhaps insisting on having my needs met would not seem so anachronistic. Instead, I am seen as entitled when I meet my needs, and yet pitied for having needs at all. How pathetic, they seem to say. How cringe.

When they tell us we’re people first — that we shouldn’t say “disabled people” — it feels as though they are worried that one day we will implicate who has disabled us and who continues to poison and maim us as we try to heal. Their brand of capitalism is the same one that demands endless growth, even from those of us who do best lying fallow in the afternoons. The ones who insist on ceaseless cheerfulness. I have pulled myself up by more bootstraps than I can count. But I know this: After you have pulled yourself up, the horse carries you.

Their brand of capitalism is the same one that demands endless growth, even from those of us who do best lying fallow in the afternoons.

Part of the trouble with invisible disabilities is that you keep having to explain yourself. I’m not lazy, I want to say. And yet, in certain contexts, I am, in turns, “a hearie,” “a walkie,” and so on. In those moments it is my turn to be a facilitator: to make space, to create connections, to meet needs where I can, to help patch the way between here and access. This means knowing who needs to leave at what time so they can make it to work; who needs to be on the left side of the stage to hear; or who might need the Advil or Clif Bar or extra pair of socks I have stashed in my bag. I move as deftly as I can, remembering to create for others the conditions for getting their needs met, one cell in the body of a complex organism. This is what community care can look like. Sometimes it means giving and other times, receiving. Sometimes, it simply means making sure that everyone in the group knows where I am and where to find me so that I can troubleshoot. At the very least, my work is to help create an atmosphere where those who have needs know they belong. All good activism, even street protests, begin with consent; people should be able to move back or away or into a different mode at any moment, without shame. The group’s work is to respond with care to the needs of its individuals, even when those needs shift.

I am still learning, fucking up, apologizing, fumbling forward. If inquiry offers me the gift of understanding myself as someone who has been disabled in certain contexts, it also yields this knowledge: In other contexts, I am not. And in those cases, I have the obligation to tear down barriers that, while not an issue for me personally, oppress others. While my disabilities’ invisibility in some contexts robs me of being taken seriously, at times being able to be covert, to fly under the radar, lends me a certain kind of power. It comes with responsibility.

Some of my favorite protests are the ones where I can play a specific role, one that feels well-worn and comfortable for me, without having to do the heavy lifting of organizing. Let me block traffic or wrangle reporters or talk to the cops, things that might feel scary for younger activists, without the actual, real work of logistics and getting people to show up. Often at protests, I feel like something between a camp counselor and a firefighter, spending my time handing out Clif Bars and extinguishing conflicts before they can overtake the group (and the message we’re trying to send).

In the summer of 2019, a coalition of groups staged protests outside of the ICE building — to protest family separation at the border and Trump’s draconian immigration policies — in downtown San Francisco every day during August, with a different group “adopting” a day during the month. I went to six or seven events. My favorite was when I was asked to be the police liaison for a coalition of disability justice groups who had committed to anchoring the action. I find freedom in being somewhat mercenary.

And yet, in certain contexts, I am, in turns, “a hearie,” “a walkie,” and so on. In those moments it is my turn to be a facilitator: to make space, to create connections, to meet needs where I can, to help patch the way between here and access.

I am not big or scary, but I have a set of skills. I know how to talk a security guard out of messing with our equipment. I know how to move the larger group to protect a higher-risk few. I know when a tense situation can be dissolved with singing or when to raise the energy of the group with a chant. I know how to watch the police and to recognize their gear. I can translate what they’re wearing into an understanding of how they are reading our action. Do they read us as a threat? Should we read them that way? I have learned to do this so that those who should be at the center can focus on the message. I am fluent enough in these to “Show them who’s boss.” I’m there to do my job invisibly: decentering myself and using my skills as a crowbar. My work in those moments is to leverage my experience and my credibility to create ease, a feeling of safety, and ample space, so the organizers can do their real work of delivering the message, rather than worrying about the cops.

The message is this: No body is disposable. No one is illegal. Migrant justice is inextricable from disability justice.

In the middle of the action, things are calm. What I know is activism in San Francisco is safer than most other places — especially places where they aren’t used to it. I’ve done actions in rural logging towns and in smaller cities like Charlotte, North Carolina, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, and I’ve learned: It’s more dangerous when the police are scared or surprised or don’t know what to expect. It’s riskier when they are excited to get to try out all their pretty, shiny toys on you, not knowing how they really work. Boring is the best case scenario. Everyone knew their role. I, as a “walkie,” roamed the crowd, to watch the police, communicate with them when necessary, translate information back to the group and keep folks from coloring too far outside the lines. Sometimes that means honoring our shared action agreements not just to protect ourselves from becoming targets, but protecting the more vulnerable folks we’re working with. Acting as a beacon and a deterrent.

Afterward, I went home and spent the next couple of days lying down as much as possible, feeling the impact of my heels on the asphalt radiating up into my lower back, the exhaustion of holding myself upright and alert. The residual adrenaline I feel from my PTSD needs time to dissipate, no matter how chill the cops are. Sometimes, this healing is private, but built-in recovery time is a necessary part of my activism. I am not as elastic as others.

If reminding people I am disabled is what it takes to let people know I have needs or they should quit being ableist, then so be it. If I have to out myself — to tattle on my chronic pain — to get a chair, fine. I will never apologize for it or undermine myself again. I will never downplay what I feel or what I need. I am worth getting my needs met, with or without a disability. I am worth taking up space. And, I have learned, if I do not take up space in the places I fear I am not enough, there will be no space for me at all.

***

Christy Tending (she/they) is an activist, writer, and mama living in Oakland, California. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Catapult, Electric Literature, Permafrost Magazine, Newsweek, and Insider, among many others. Her first book, High Priestess of the Apocalypse, is forthcoming from ELJ Editions. You can learn more about her work at www.christytending.com or follow Christy on Twitter @christytending.

Editor: Krista Stevens

Copy editor: Cheri Lucas Rowlands

Two political prisoners arrested for questioning the Thai monarchy have been on a life-threatening hunger strike for over a week. The government has met their demands for the right to free expression with silence.