NYC Pride – 6/25/2023

My name is K. Yang, I’m a former trans rights activist & LGBT non-profit whistleblower. I was just kicked, hit, pushed, mobbed by dozens of people in Washington Square Park.who identify as

called me “bitch” & assaulted me. @KnownHeretic @bjportraits pic.twitter.com/4J9AaFXSEf

— Stop Female Erasure / K Yang (@StopXXErasure) June 25, 2023

A brilliant and brave woman I know named K. Yang posted a video from NYC Pride on Sunday, showing her being mobbed by a gang of Pride-goers, frothing at the mouths, rabid with anger at a lone woman daring to stand up for herself and millions of girls and women around the globe.

Holding a sign reading, “Defend female sex-based rights,” and another with the words, “Trans ‘Rights’ = Big Pharma, Big Banks, United Nations Propaganda,” Yang was verbally abused, threatened, and assaulted by a number of men (surely claiming any identity but “man”) and screamed at by women in the crowd. Yang, once a trans activist who realized the (ever expanding) 2SLGBTQ+ was a misogynist, corporate con and began calling it out, tweeted:

“Two [men] followed me calling me a “bitch.” They began to explain misogyny to me. I was called a “cis bitch” by a [man] who claims to be a [woman]. Another begins the gang assault by hitting me, yet another kicks me from behind. #CisIsASlur“

Many of you have likely observed the endless stream of fear-mongering propaganda force-fed to us by mainstream media outlets, politicians, and NGOs, insisting “attacks” against the “2SLGBTQ+ community” are on the rise. In the month leading up to Pride, these claims have been amplified in what has become an ongoing war against reality.

On June 6, the Human Rights Campaign declared a national “state of emergency for LGBTQ+ people in the United States… following an unprecedented and dangerous spike in anti-LGBTQ+ legislative assaults sweeping state houses this year.”

What they are referencing is not, in fact, any actual “assault” — legislative or otherwise — but a series of bills passed in various red states preventing youth from being given harmful puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries on account of a declared “trans” identity.

What has happened is that states like Oklahoma, Iowa, North Dakota, and Kentucky (among others) have passed laws preventing the medical transition of kids. This legislation protects minors from making adult-influenced decisions that cause irreparable damage, rendering youth sterile before they have even had a chance to explore intimate relationships and their sexualities. The long term effects of these drugs are both known and unknown, leading to bone loss, increased risk of cancer, and all sorts of other obvious and perhaps less obvious problems related to interference in the natural, healthy development of human bodies. We don’t have enough long term research on this kind of experimentation to know the extent of the damage, but we do know there is damage.

The tragic story of Jazz Jennings, whose mother thrust him into the spotlight as a “trans child,” and who has now undergone four “sex reassignment” surgeries, all of which have resulted in painful complications, should have acted as a warning. Today, the 22-year-old struggles with eating disorders and depression, and will likely never experience sexual pleasure or be able to have children.

You cannot simply stop puberty, feed a developing child or teen hormones that increase cancer risk and result in a host of other side-effects in adults, and assume no harmful repercussions for youth. Yet, that’s what these NGOs insist, claiming these treatments are “life-saving” and medically necessary, and that laws limiting these interventions constitute an “assault” on “LGBTQ+ people.”

The response to this legislation has been hyperbolic, to say the least, suggesting that kids feeling confused or troubled by their changing bodies and entry into adulthood flee their hometowns in search of states that will allow these interventions.

An HRC guidebook directs youth in their decision to leave their homes for “friendly states” that allow minors to alter their IDs and bodies, no questions asked, and encourage them to find their “chosen families,” described as “people who are in your life, not because of biological ties, but for love and support, to celebrate you and help you no matter what.”

This kind of rhetoric is common to trans activists, who often recommend youth identifying as trans abandon their “non-supportive” families (labelled “abusive” for failing to encourage transition) for a “chosen family,” who support and validate their transition. “Come talk to me about your secrets — your parents don’t really love or understand you, but I do” should be treated as a red flag of epic proportions, but within trans activism is normalized.

Moreover, the irony of describing a “dizzying patchwork of discriminatory state laws that have created increasingly hostile and dangerous environments for LGBTQ+ people” becomes obviously rich when we look at how women are treated by these groups. In the past five odd years, women and girls have not only lost the right to women-only spaces — including change rooms, shelters, and prisons — and lost the right to compete on fair grounds, among females, in sport, but have lost the right to speak out about this. Women who have challenged gender identity legislation and policy have been fired, assaulted, censored, threatened, blackballed, ostracized, deplatformed, and banned from social media.

And all this has been perpetrated against women with impunity while being gaslit into oblivion by public officials, the media, institutions, corporations, progressives, activists, NGOs, and human rights organizations. We are told over and over again that it is not women, but the “LGBTQ community” who are under attack and in dire need of our support.

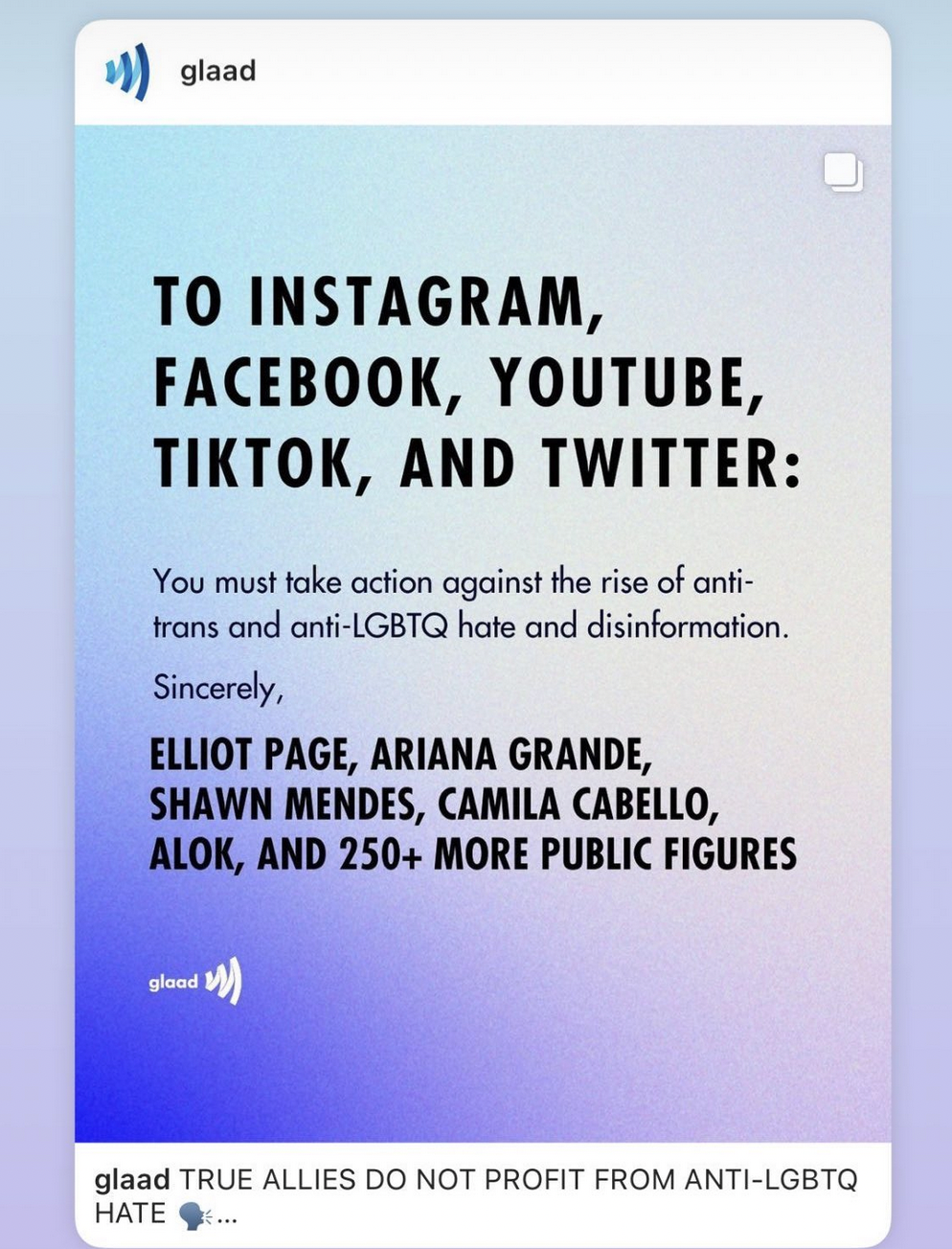

Nonetheless, yesterday, GLAAD, a non-profit originally founded to fight for gay rights (recently expanded to advocate the LGBTQ cultural revolution) published an open letter calling on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, and Twitter to “Stop the flow of anti-trans hate and malicious disinformation about trans healthcare.” Signed by a dizzying number of celebrities such as Ariana Grande, Demi Lovato, Haley Bieber, Elliot (nee Ellen) Page, and Jamie Lee Curtis, the letter claims “Dangerous posts (both content and ads) created and circulated by high-follower anti-LGBTQ hate accounts targeting transgender, nonbinary, and gender non-conforming people are thriving across your platforms, directly resulting in terrifying real-life harm.

The letter labels “misgendering and deadnaming” as “hate speech,” claiming that correctly sexing individuals or daring to acknowledge a name change is “utilized to bully and harass prominent public figures while simultaneously expressing hatred and contempt for trans people and non-binary people in general.”

By framing pushback against and discussion of the harms of transing kids as “disinformation and hate,” and claiming refusal to call men women as “dangerous,” GLAAD is able to demand censorship, insisting these social media companies “urgently take action to protect trans and LGBTQ users on your platforms (including protecting us from over-enforcement and censorship).”

It is all very urgent. An emergency. People are dying because of true statements and free speech. Not any real people, but certainly people in our imaginations. Either way, we are not used to being challenged and it is triggering.

On June 1, Marci Ien, minister for women and gender equality and youth, issued a statement to mark the start of what the Canadian government has rebranded as “Pride Season,” saying:

“While it is important that we take the opportunity to recognize the hard-earned victories of the Pride movement, we must continue pushing back on the sharp rise in anti-trans hate and anti-2SLGBTQI+ legislation, protests at drag events, the banning of educational books in schools, and calls against raising the Pride flag.”

She followed this statement with the announcement that the Liberal government would be “moving forward with the development of a new Action Plan to Combat Hate – that will address hate faced by 2SLGBTQI+ communities and, specifically, hate faced by trans people.”

Where is the Canadian government’s action plan to address the silencing, marginalization, and harassment of women who speak up about their sex-based rights and about biological reality? Where is our “feminist” Prime Minister on women’s rights and the actual assaults perpetrated against female inmates by the violent male criminals he has allowed to be transferred to female prisons?

Nowhere.

Justin Trudeau’s government didn’t stop with an action plan. On June 5, Ien announced that the government would be pledging $1.5million in “emergency funding to ensure Pride festivals stay safe across Canada.”

Safe from what? Where is the emergency?

Half of the population are losing their rights without any genuine public consultation or debate, and the government leaps to action, pouring money into a trend that is already the most well-funded marketing campaign I have seen in my life.

Today, Pride is a corporate-sponsored event that is celebrated as though it is the national religion. Dissent is unacceptable, but even if it were allowed, who is attacking Pride-goers? Nothing of the sort has been reported, nor was anything of the sort even threatened. What I did see was a lone woman mobbed by deranged, violent Pride fanatics, enraged that anyone would dare challenge their faith.

I would, frankly, never attend one of these things out of fear of being assaulted or worse, so clearly Yang is braver than I. We should all be enraged at the lack of support for women and women’s voices from those in power, who dare lie to our faces while we suffer the consequences.

The post The Pride industrial complex ignores threats against women and doubles down on the myth of 2SLGBTQ+ ‘hate’ appeared first on Feminist Current.

This extraordinary profile of Clarence and Ginni Thomas—he a Supreme Court justice, she among other things an avid supporter of the January 6 insurrection—is a masterclass in everything from mustering archival material to writing the hell out of a story:

There is a certain rapport that cannot be manufactured. “They go on morning runs,” reports a 1991 piece in the Washington Post. “They take after-dinner walks. Neighbors say you can see them in the evening talking, walking up the hill. Hand in hand.” Thirty years later, Virginia Thomas, pining for the overthrow of the federal government in texts to the president’s chief of staff, refers, heartwarmingly, to Clarence Thomas as “my best friend.” (“That’s what I call him, and he is my best friend,” she later told the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.) In the cramped corridors of a roving RV, they summer together. They take, together, lavish trips funded by an activist billionaire and fail, together, to report the gift. Bonnie and Clyde were performing intimacy; every line crossed was its own profession of love. Refusing to recuse oneself and then objecting, alone among nine justices, to the revelation of potentially incriminating documents regarding a coup in which a spouse is implicated is many things, and one of those things is romantic.

“Every year it gets better,” Ginni told a gathering of Turning Point USA–oriented youths in 2016. “He put me on a pedestal in a way I didn’t know was possible.” Clarence had recently gifted her a Pandora charm bracelet. “It has like everything I love,” she said, “all these love things and knots and ropes and things about our faith and things about our home and things about the country. But my favorite is there’s a little pixie, like I’m kind of a pixie to him, kind of a troublemaker.”

A pixie. A troublemaker. It is impossible, once you fully imagine this bracelet bestowed upon the former Virginia Lamp on the 28th anniversary of her marriage to Clarence Thomas, this pixie-and-presumably-American-flag-bedecked trinket, to see it as anything but crucial to understanding the current chaotic state of the American project. Here is a piece of jewelry in which symbols for love and battle are literally intertwined. Here is a story about the way legitimate racial grievance and determined white ignorance can reinforce one another, tending toward an extremism capable, in this case, of discrediting an entire branch of government. No one can unlock the mysteries of the human heart, but the external record is clear: Clarence and Ginni Thomas have, for decades, sustained the happiest marriage in the American Republic, gleeful in the face of condemnation, thrilling to the revelry of wanton corruption, untroubled by the burdens of biological children or adherence to legal statute. Here is how they do it.

We are now a year removed from the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade. In the flurry of protests that followed the late June 2022 decision, LGBTQ-identified persons and organizations paid a surprising amount of attention to the Court’s decision. The rainbow flag was a mainstay at Dobbs protests. Even a shallow dive into written backlash against the Court’s decision revealed that LGBT people were concerned about Dobbs at least as much as women in heterosexual relationships were, despite the latter’s lopsided contribution to actual abortion numbers. The most obvious reason for the former’s concern was Justice Clarence Thomas’s reference, in his concurring opinion, to reconsidering other “substantive due process precedents,” like those in the Obergefell and Lawrence v. Texas decisions.

But some share of the political angst no doubt comes from the fact that there has been a surge in LGBTQ self-identification among young adults who do not display homosexual behavior. That’s right. New Gallup data analyses put the LGBT figure among Zoomers (i.e., those born between 1997 and 2012) at 20 percent. Data from the General Social Survey—a workhorse biennial survey administered since 1972—reveal that the share of LGBTQ Americans under age 30 exploded from 4.8 percent in 2010 to 16.3 percent in 2021. No matter the data source, it’s clear that in 11 short years, LGBTQ identification among young Americans tripled. And yet under-30 non-heterosexual behavioral experience, while climbing, remains just over half that figure, at 8.6 percent (in 2021).

Sexual behavior once comprised the key distinction to homosexuality. Homosexuality, however, has given way to ideological and political self-identity. In light of this shift away from using behavior to self-identity in defining homosexuality, LGBTQ antagonism to the Dobbs decision starts to make more sense. In fact, we should have seen it coming. In a study published last year in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, my coauthor Brad Vermurlen and I found that the key predictor of adult attitudes about treating adolescent gender dysphoria with hormones or surgery—a topic you might not equate with abortion rights—was not age, political affiliation, education, sexual orientation, or religion. The best predictor was whether the respondent considered themselves pro-choice about abortion.

In 11 short years, LGBTQ identification among young Americans tripled. And yet under-30 non-heterosexual behavioral experience, while climbing, remains just over half that figure, at 8.6 percent (in 2021).

This surprised us. In hindsight, it shouldn’t have. Opinions about abortion and gender medicine tend to turn on basic differences in how people understand the human person, their own body, others’ bodies, and the very ends for which we exist. Sociologist James Davison Hunter mapped this out in his 1991 book Culture Wars. In what he described then as the “progressive” worldview, bodily autonomy is paramount. We determine who we are, and we should be free to do so through body modification and the control and redirection of bodily processes. In what Hunter called the “orthodox” worldview, on the other hand, bodily integrity trumps autonomy and self-determination. As the Heidelberg Catechism famously opens, we are not our own, but belong—body and soul—to our savior Jesus Christ. Bodies—systems, parts, organs, and processes—have natural purposes and ends toward which they are objectively ordered. They are to be received as a gift. The two are strikingly different perspectives about the self.

The prospect of motherhood can no doubt undermine one’s sense of self-rule over one’s own body. This is particularly the case if you understand your body as “belonging” to you, and that you rule over it by making choices for it. You can permanently alter it, be harmed by it, or be at odds with it. It’s not surprising that a pregnancy can scare people, because—in the progressive worldview—you have the right not to be pregnant, just like you have the right to self-identify as you wish. It’s a cousin to asserting you have the right to body modification in service to your own self-definition. (And why should being a minor prevent such rights?) Dobbs appears to undermine all this; its three dissenting justices claim that “‘there is a realm of personal liberty which the government may not enter’—especially relating to ‘bodily integrity’ and ‘family life.’”

As previous legally effective arguments about fixed, stable sexual orientations give way to malleable sexual and gender self-identities, it’s tempting to wonder whether we’re not simply speaking about different worldviews—as Hunter’s terminology maintained—but alternative religious systems. LGBTQ, after all, is a big-tent system that contains its own rituals, creedal commitments, forms of worship, sacred items and places, a liturgy, a calendar with holy days, appropriate confessions, salvation accounts, martyrs, moral codes, and magisterial representatives. Religious belonging commonly begins with self-identification. Just as not all Christians practice their faith, so too not all self-identified LGBTQ persons demonstrate behaviors long associated with the movement. And just as there are many moral questions that divide Christians, so too is this the case in the LGBTQ world. But the emotional depth of disagreement here suggests core religious belief systems are clashing.

Language and authority structures are no less pivotal in the LGBTQ world than they are in our own faith. British social theorist Anthony Giddens—a leading public intellectual in England and one of the more famous sociologists alive today—articulated the importance of sealing new ideas with new words in his 1992 book The Transformation of Intimacy: “Once there is a new terminology for understanding sexuality, ideas, concepts, and theories couched in these terms seep into social life itself, and help reorder it.” This is why Hunter described culture (in his book To Change the World) as the power of legitimate naming. With regularity we now find ourselves wrestling with our opponents over basic terms. But sometimes even new religious movements get ahead of themselves, bungling their systematic ontology. As one Wall Street Journal columnist noted recently,

Those protesting the (Dobbs) ruling have a particular challenge in that there is now some disagreement among themselves about what exactly they are advocating and for whom. The left has been engaged in a confusing internal debate about what a woman is.

Indeed, this may prove to be a bridge too far. The recent flare-up involving Bud Light and Target Corporation, and the mystifying battle over whether drag queens should read stories to other people’s children, suggest that many people of any and no faith are fed up with the proselytizing. There’s plenty of religious tolerance in libertarian America—including among Christians—but little interest in revolutionary ideas about “queering” the gender binary. Sexual difference is not a problem requiring a solution. The Human Rights Campaign, as close to “headquarters” as it gets, should have seen this coming. Instead, it declared an LGBTQ “state of emergency” in the United States, akin to a plea for religious tolerance. But when parents’ rights are openly undermined by their efforts, the HRC should not be surprised when people of all faiths have heard enough talk about children’s “bodily autonomy,” or their supposed ability to express informed consent. As we are witnessing, mothers and fathers remain a powerful bastion of reason in our new post-gender turn, because they display with and in and through their bodies the reality that Roe sought to hide or ignore.

There’s plenty of religious tolerance in libertarian America—including among Christians—but little interest in revolutionary ideas about “queering” the gender binary.

Christians have a distinctive anthropology of the human person and a better, happier long-term vision for human flourishing. Unfortunately, many of us are unable to articulate it. But the time for making explicit what we believe—the true, the good, and the beautiful—is now. While it remains to be seen how our post-Roe society will look and how the present cultural conflict will play out in courts, legislatures, and around kitchen tables, a few things are certain. Subtlety won’t cut it. Gradualism won’t do. Charity—courtesy, kindness, and love—is always in good form. But don’t think that being deferential or nice will evangelize effectively or preserve our longstanding vision of the human person and its design, purposes, and ends from its ideological challengers. To paraphrase one old saint’s remarks about laws concerning marriage and education, it is in these two areas that Christians must stand firm and fight with toughness and fairness, and—if I may add a category—good judgment. A world, and not simply one country, is at stake.

“The thing you love most when you are thirteen is the thing you love forever,” Adi says. He has his leg crossed over his lap, hand on his knee in a scholarly position.

“You’re bound to it,” I add, leaning forward. “You can’t put it down.” I am drunk and twenty years old and my voice aches—I have been shouting for most of the night, but the music isn’t really that loud. I tilt my body toward the group to understand them, a hand around my ear in what feels like a theatrical gesture. The boy Adi and I are chatting with is soft-spoken mumbling-drunk, with dark eyes that scrunch up beautifully when he smiles. “Say again?” I repeat over and over. He stands up to grab a beer off the table between us, jeans slipping down his narrow hips, and Adi and I look at each other with our eyebrows raised. I giggle and he glares back—we are always passing sly glances back and forth like handwritten notes between school desks.

The boy’s name is Alan and he is disarmingly handsome, the kind of man I would have avoided in high school out of shame and fear. I am fascinated by beautiful men, their ease of movement, the carelessness of their limbs. I watch them and think of Margaret Atwood: “When I am lonely for boys it’s their bodies I miss…My love for them is visual: that is the part I would like to possess.” A desire that stems from a sense of possession; I would like to inhabit them, to take up space and know that everyone around me feels grateful. To be a beautiful white man and never know fear—how simple and glorious.

There are moments when the light passes just right over the high point of someone’s cheekbone and I imagine my whole life as it would have been in a different universe, tracing the events of this imaginary life from that spot on their face to my death. In another world, I fall in love with this boy who shares my taste in music and laughs generously at my less-than-clever drunken commentary. In another world, things are easier. In this world, we dance and sing Talking Heads to each other across the kitchen as we spin in circles: I guess that this must be the place. In another world, I do not go into the bathroom and stare at myself in the mirror, watching my reflection careen across the glass. In another world, I do not make myself sick with want and worry at every turn.

Alan sits back down beside Adi and we talk about California. Whenever I meet someone who’s left California for New York, they can never shut up about being from California and how much they miss it, as if they hadn’t chosen to leave. Alan tells us that in California he met Paul McCartney once, and I clutch my hand to my collarbone in a mockery of a swoon because that is what I loved when I was thirteen, what I am bound to forever, the thing I cannot put down. There will always be a part of me that starts at the mention of The Beatles, that blip of recognition when you come across your own name in an unexpected place.

“I know this sounds corny,” he says, “but I swear to God he just made the whole room brighter.”

The enthusiasm in Alan’s voice strikes me. He tells me he saw Arctic Monkeys seven times in one year because he was in love with Alex Turner and again I am envious of him, this time because I never allowed myself to notice any women as a teenager. I instead fixated on male celebrities and characters, as if I could convince myself that I loved them the way I was supposed to love them. I want to know, suddenly, if he went to those concerts because he knew he wanted to see the lead singer, or if he had convinced himself it was because he just really liked their music. But I do not ask. Instead I stare at the mole on his right hip, made visible by his low-slung trousers. The mole is largish, about the size of a dime, and raised slightly. I try to imagine myself putting my mouth on it, on this bit of flesh which has so captured my attention, and am immediately repulsed.

This is where it always stops, the insurmountable stutter of my fantasies. This is the part I find difficult to explain even to myself, the way I can simultaneously want and so clearly not want. I picture the thoughts in my mind as a strip of film: reversed, softened, made grand by my drunkenness, mimicking how things are always beautiful onscreen. I can desire this boy as if from afar rather than with the blistering intensity I feel when a girl sits too close to me on a stranger’s bed at another party as she speaks to someone else, the air soft with smoke, my insides folding in on themselves. The universe is reduced to the point at which our hips are touching and I cringe at the clichés this meaningless contact inspires in me.

I think about Paul McCartney, his boyish features still apparent in old age: wide, down-turned eyes and full cheeks and always that charming smile. My favorite Beatle fluctuated between him and George, whose quiet demeanor intrigued me; I have always been inclined toward the fantasy of quiet men. I would watch videos of early performances for hours, unable to tear my eyes away from George’s legs, how dreadfully slender they were in his dark slacks as he stood off to the side of the stage. Ringo was about as attractive to me as a post (though darling) and John looked far too much like my father, so my desire, or what I thought was desire, had to be cast onto Paul and George. This was how I amused myself throughout most of my early adolescence: poring over photographs and watching footage from decades earlier of a half-dead, long-fractured band. Maybe The Beatles were easy to love because the group had already run its course—I could discover new information but nothing new would actually happen, and there was a comfort in this impassable distance. I cannot say that if, in another world, I would have been reduced to tears like all the girls in A Hard Day’s Night, wordlessly mouthing George-George-George as the crowd around me fell into hysterics, or if the illusion would have been ruined by seeing them in the flesh.

I think about the sightless stare of a Roman bust in a museum, terrifying and opalescent, made lovelier by the fact that I cannot touch it. In another world, I step past the line on the floor of the gallery and run my fingertips over the marble despite the docent’s protests. In another world, I tell Alan the truth: I will never be happy with what I have or what I am.

Says Alan of Alex Turner: “I don’t think I even realized who he was, the first time—he walked right past me, in those fucking Chelsea boots, and I was just so turned on,” and I laugh because it’s always those fucking Chelsea boots. The Beatles wore them, too.

I tell Alan that I’ve been in the same room as David Byrne, white-haired and gracious, those darkly intense eyes gentle with crow’s feet and laugh lines, and Alan concedes that this is indeed “very, very cool.” In high school, I would have recorded such a statement from a hot boy in my journal. Now it just seems obvious. It was a screening of a documentary about competitive color guard that David Byrne had produced, with a Q&A afterwards. My friend was a huge fan of Talking Heads and I came along because I was a huge fan of her; I barely paid attention to the the Q’s that David A’ed because I was swept up in the thrill of watching someone I love watch something she loves. Her sardonic voice was made sweet as she described her enjoyment of the evening, tucking herself into a red raincoat ill-suited to the frigid March weather. Now whenever I listen to Talking Heads’ bizarre, frenetic music, I think of her with a twinge in my chest not unlike heartburn. People sometimes ask me about her, mention her to me in passing: didn’t you know—? weren’t you—? I smile, tight-lipped, and nod. In another world, I tell Alan that I buy the shampoo she used because I miss the smell of her dark hair as it wafted toward me, head on my shoulder.

“Stop, don’t talk about it,” I say to Adi when he mentions her. “If I talk about it, I’ll cry.” I’ve been saying this for the past few months, begging friends to help me maintain the illusion that I wasn’t deeply hurt by her decision to return to Texas. The less we say about it the better.

We talk about how it would be nice to leave New York, but none of us stay away for very long. We all have our reasons. Mine is a sense of obligation to my younger self, the anxious, dirty-haired creature who collected postcards from Manhattan and watched The Beatles with a thumb-sucking compulsion and dreamt of someday ending up in a different body in a different place. She needs me to remain in this city, for at least a little longer, regardless of the people who come and go and the women I watch and want and the men I may or may not speak to at parties.

Most people have left the party by the time Adi and I declare mutiny and claim the aux cord for ourselves. Alan stretches as he makes room for me on the couch. His grey sweatshirt again rides up across his belly and I think about Saint Sebastian: his long, muscled torso, the agony and eroticism of his death as it is depicted in art. How I should like to be an arrow and glance off the flesh of some beautiful thing before falling, unbroken, to the ground. I think about Louise Bourgeois’ drawings of Saint Sebastienne as a martyred pregnant woman, the same sketch repeated over and over in a monotonous procession of bodies, smudged and headless: the grotesquerie of gestation. How awful is the practice of becoming alive.

Weeks later in Boston, my friend Laura and I discuss the dreams we’ve been having since we were little girls, nightmares in which we are pregnant despite never having had sex and everyone tells us we should be grateful to be so immaculate. But Laura is Jewish and I was never baptized and neither of us believe in anything beyond the miracle of blood and tubing that is the body itself. The nightmares persist as a reminder of what that body may be capable of, both within and without ourselves.

Hours past midnight, Adi and I walk to my apartment from the party. “Do you wish you were straight?” I ask him. He shrugs. I say, “I do, sometimes. I think it would be easier. Don’t you think it would be easier?” I hope he knows I mean easier just in the simple act of existence: would it be easier to be alive? Would I hate myself for something else if not this?

Adi doesn’t answer, but his gaze is warm behind his glasses, his jaw set in the near-pout he wears when he considers something seriously. He is a dear friend, one of the first I made at college, and one of the first people I heard utter the word “lesbian” with a gravity that implied strength and meaning rather than disdain. I lean into his shoulder and we stand like that, quiet, until Adi’s Lyft arrives.

A month and some weeks later, I stand in the living room of another apartment, once again speaking loudly over the music to an acquaintance. The theme of the party is blue, as in Maggie Nelson’s seventh book, as in Derek Jarman’s final film, as in Nina Simone’s debut album Hey, blue, there is a song for you. My acquaintance’s eyelids are a bright teal, in lovely contrast to her copper hair that falls into her face as she leans in to hear me. I feel a touch at the back of my neck and I turn around and it is Alan once again, tucking the tag back into the collar of my shirt. This is an urge I have to resist when I glimpse a misplaced tag or loose thread on a passing stranger, the same compulsion that makes me check the locks on the front door nightly before bed, a desire for security through control. Alan has not shied away from this impulse to put things in their proper place. His face, cast in cobalt, grins back at me when I turn.

Already I can feel the sense of infatuation ebbing away as I greet him, repeat my name, raise my arms around him in a clumsy approximation of an embrace. Names are important, and it bothers me on a primal level when people forget them. Alan is still handsome with his watery-drunk smile and half-lidded eyes. The man asleep, like the man in quietude, was another adolescent fixation of mine: a feral animal tranquilized to be observed more safely.

The apartment is so small and so full of bodies that we can hardly do more than shuffle in time with the music. While waiting for the bathroom, I get into an argument with a man about Kate Bush, and how would he understand the anguish conveyed in her warbling falsetto, anyway? I don’t know what’s good for me I don’t know what’s good for me.

I spend the next two years moving farther away from my body. I try to date casually and discover that I am perhaps incurably afraid of intimacy. I become catatonic in the presence of my own desire, though I spend a summer trying to convince myself that it’s the heat and humidity rather than the rush of blood in my ears that makes me nauseous every time someone tries to touch me. I sit across from a man on the subway and stare at the soft curve of his jaw as he tilts his chin downward; his dark eyes rove across the pages of a book whose title I can’t quite make out. In another world, it is the 1950s in the United States of America and I am engaged to this beautiful man whom I will never love and this is better, somehow. It’s a mid-century sitcom marriage where we sleep in separate beds and only ever kiss on the cheek. I am miserable, but it’s better than being miserable in reality because in this dream I have what feels like a justifiable reason to be miserable. My life is unfulfilled, uninspired. I see East of Eden at the cinema and masturbate to the thought of James Dean the same way I did as a teenager, silently rocking back and forth in a chair, disgusted by the idea of actually touching myself. In this world I never figure out that I’m a lesbian because I could barely figure that out in 2016 with contemporary resources. It’s easier anyway, following an assigned path, filling a prescription month after month at the pharmacy—doctor’s orders. In another world, my sadness has sharp contours, clear edges that I can press into my skin. It is not amorphous and it does not expand to fit every space I inhabit.

I try to describe some of this world to Laura in a taxi, drunk and newly twenty-two on the hottest night of last summer. “Do you ever wish that’s how it was?” Laura tells me she doesn’t—she’s tired, and she turns away from me to look out the window as we arrive at my apartment. “It’s almost light out,” I say to change the subject, waving a hand in the direction of the sky.

I am glad that I didn’t tell her the extent of my dreams, the tragic details that lull me to sleep. It is so perversely appealing to me, this fantasy of a loveless, sexless, meaningless existence in which I am freed from any expectations of self-possession or choice. In another world, no one asks me what I want to do with my life because they do not assume that I will ever do anything. I know this way of thinking is self-indulgent and wildly privileged, and that Laura’s reaction to my modest proposal was appropriate: a snort that went from surprised to scornful, a firm “No.” And yet I greet sleep that morning with dreams of pin curls and bathroom tiles scrubbed clean and never being touched by my beautiful imaginary husband, asleep beside me in his bed across the room.

Adi and I watch A Hard Day’s Night and he touches my arm when he notices I’m crying and we can pretend, briefly, that we knew each other when we were thirteen. Laura tells me that she is a lesbian, too, and this more than anything makes me feel like I may someday be able to overcome my shame because Laura is someone who did know me when we were thirteen. Through my love for her I may be able to forgive myself the trespass of being who I am. She tells me she sometimes still dreams of having children, but since realizing she is a lesbian she is no longer so afraid of the possibility.

I see David Byrne again and this time he sings. I wonder what it’s like for him to play those songs from another time when his band all lived together in the same room, cutting each other’s hair, muddling through waves new and old only to end up estranged forty years later—no talking, just head. John, Paul, George, and Ringo were dogged by other people’s hopes of a reunion from the day The Beatles broke up until that night at the Dakota, and I wonder if it bothered them to know that the best thing they ever did was be part of something beyond themselves. In another world, rooftops are only for concerts, never for leaping. In another world, I am not afraid of heights or the way my body moves through time and space, toward the ground or toward another body.

***

Rumpus original art by Lisa Marie Forde

It is June, and Pride has flooded the world. Pride is on display in the streets, in stores, in schools, and even at the White House. All of the great and the good (or at least the wealthy, famous, and powerful) are affirming the triumph of the sexual revolution, and some even applaud transgender toddlers and sadomasochism on parade. Affirmation is increasingly mandatory; the devotees of Pride are literally taking away lunch money from low-income children because their Christian school dissents from some aspects of the rainbow creed.

Christians should not be surprised when many of the rich and powerful mock God and scorn His people, and boast of indulging their every material desire and sexual whim. We have been warned about the world and its rulers. But this month also offers us encouragement to resist the depredations of the sexual revolution. June 24th is this weekend, and it is not only the feast day marking the birth of John the Baptist, but also the anniversary of the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade’s false declaration that there is a constitutional right to abortion. John the Baptist is an appropriate hero of faith for us this month: he began his life as a witness for the sanctity of unborn life, and ended it as a martyr for marriage.

Before he was even born, John testified to the sanctity of all unborn human life. The sexual revolution requires abortion as a backstop against the consequences of the promiscuity it promotes, but John shows why the personhood of humans in utero cannot be denied without embracing grave heresy about Christ’s nature.

John the Baptist is an appropriate hero of faith for us this month: he began his life as a witness for the sanctity of unborn life, and ended it as a martyr for marriage.

John’s ministry testifying to Jesus began before either was born. According to Luke’s account:

when Elizabeth heard the greeting of Mary, the baby leaped in her womb. And Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit, and she exclaimed with a loud cry, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb! And why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For behold, when the sound of your greeting came to my ears, the baby in my womb leaped for joy.”

The unborn John’s recognition of the unborn Jesus was a miracle that demonstrates the value of human life in the womb in several ways. First, the passage shows that the fetal John the Baptist and the embryonic Jesus were human persons congruous with their adult selves, and that both were already participating in their divine missions.

Second, the recognition of Jesus as Lord early in Mary’s pregnancy testifies to His divinity even as He grew within Mary’s womb. This divinity at conception is why Christians honor Mary as the Theotokos, the God-bearer. This title is affirmed by Orthodox, Catholic, and Reformed Protestant teaching, and is attested to by many ancient sources, such as Ambrose of Milan’s great Advent hymn, “Veni Redemptor Gentium” (“Savior of the Nations, Come”), which in verses 3 and 4 declares both Jesus’ full divinity and full humanity in the womb.

Third, this episode demonstrates the full humanity of all unborn persons. To claim that the unborn are not fully human is necessarily to claim that Jesus was not fully human while in Mary’s womb. But the Bible insists that His humanity was like ours in every way but sin. Denying the full humanity of the unborn therefore requires either also denying the full divinity of the unborn Jesus (thereby rejecting the reason for the unborn John’s joy and the teaching of the ancient church) or asserting that Jesus’ full divinity was present without His full humanity. Either is an enormous heresy.

Just as the beginning of John’s life shows us the value of unborn human life, the end of John’s life shows us the importance of marriage. At the end of his life John sacrificed himself to bear witness to the inviolability of marriage. As recorded in the Gospel of Matthew, “Herod had seized John and bound him and put him in prison for the sake of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife,” because John had been saying to him, “It is not lawful for you to have her.” John was then executed at the request of Herodias, after Herod promised a favor to her daughter.

John could have kept quiet on this matter, contenting himself with calls to repentance that did not single out the powerful by name. He could have said that Herod’s sexual conduct was not actually a serious sin worth worrying about, that God doesn’t really care about what people do in the bedroom. He could have chosen to recant in the hope of saving himself after he was imprisoned. But there is no indication that John wavered or doubted his declaration that Herod was wrong to take his brother’s wife for himself.

John took his stand for marriage and fidelity, and he held to this position to his death. And Jesus allowed this martyrdom. Jesus could have told John to ease up in condemning Herod’s sexual sin—that it was not that bad, or even not sinful at all. But Jesus did not do this. Rather, His teachings contain many hard words for us, including condemnations of the sins celebrated by Pride. Jesus calls us in the condition he finds us, but He also calls us to repent of our sins, including sexual ones.

The lurid details of John’s death highlight how sin grows when indulged. Herod did not really want to execute John, but he found himself so entangled by his sins of lust and pride that he felt compelled to add evil to evil by ordering John’s death. And so John the Baptist, the wilderness ascetic whom Jesus declared to be the greatest man born of woman, died as a martyr for marriage.

This is a reminder of how seriously Christianity takes marriage and sexuality. The union of husband and wife is both a symbol of Christ and the church, and the vocation that most of us are called to. Marriage is the basis of civilization and culture in this world, and a sign of our union with God in the world to come.

This should encourage us as we are beset by the celebrants of Pride. The Christian path is the way of Christ, which is almost always contrary to the habits and desires that prevail in our culture. This often means worldly suffering, rather than worldly celebration. But we know that the defense of life, marriage, and chastity is a service to God, and He will ensure that our labor is not in vain.

A lawsuit targeted a school district and the State of Florida over restricting access to a book about a penguin family with two fathers.

Early in 2019, the men’s razor company Gillette raised eyebrows with a new commercial. The ad depicted stereotypically disordered male behavior—aggression, catcalling, and a “boys will be boys” indifference to both—and contrasted it with a new generation of men taking a stand against that patriarchal past: a father breaks up a fight between two boys, a young man cuts off another’s unwanted advances toward a female stranger.

Many on the right complained that Gillette drew a glib equivalence between masculinity and toxicity, and the commercial was admittedly both myopic and preachy. But the conservative dismissiveness of the ad largely settled into a defensive, abrasive machismo. The ad was simplistic, but its critics missed an opportunity to think through the meaning of masculinity, and about the importance of male—and especially paternal—role models.

Conversations about sex and gender are surely just as difficult now as in 2019. Any talk about masculinity can easily veer into the same sclerotic patterns of the Gillette hubbub: a left that paints with uncritically broad brushes, and a right that gets defensive and dumbs down its beliefs. Richard Reeves’s latest book, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do about It, manages to avoid predictability, blending statistical insight and easygoing wit to craft a fruitful exploration of the male malaise.

Reeves, a liberal economist at the Brookings Institution, bookends Of Boys and Men by presenting the educational, economic, and cultural challenges men face, and he proposes policy and social solutions for each. They’re all insightful and (unsurprisingly) subject to debate, especially, in my view, his discussion of fatherhood and marriage. But one of the most important lessons of the book—which Reeves introduces to reassure readers that they can care about both women’s equality and men’s struggles—is that “we can hold two thoughts in our head at once.” In that vein, we can disagree, even deeply, about some of Reeves’s premises or proposals, while also recognizing that Of Boys and Men models the sort of intellectual dexterity needed to tackle complicated matters in our polarized times.

Any talk about masculinity can easily veer into the same sclerotic patterns of the Gillette hubbub: a left that paints with uncritically broad brushes, and a right that gets defensive and dumbs down its beliefs.

Men Falling Behind

Reeves begins his book by pointing out how boys are falling behind in the classroom. He surveys data showing they are 14 percentage points less likely than girls to be ready to start school at age 5, as well as 6 percentage points less likely to graduate high school on time. Look ahead at college, and young men are 15 percentage points less likely to graduate with a bachelor’s. Women are narrowing gaps between themselves and their male classmates in typically male-dominant subjects (such as STEM), while stereotypically female subjects like nursing and teaching remain so.

Men are also being outdone in the job market. Worries about the wage gap—which Reeves handles with careful nuance—or about a C-suite glass ceiling have some legitimacy, but overemphasizing them paints an incomplete picture. The lack of female representation among Fortune 500 CEOs tells us that a small—albeit influential—proportion of men are doing very well. But by the same token, the people struggling the most economically are more likely to be men. An astounding one-third of men with only a high school diploma (approximately 5 million men) are out of the labor force.

To address these labor market problems, Reeves draws from the women-in-STEM push and calls for similar efforts for men in health care, education, administration, and literacy—or as he calls it, HEAL. In the same way that Melinda Gates pledged $1 billion to promote women in STEM, Reeves proposes an equal “men can HEAL” push. He envisions a combination of government and philanthropic funds for training and scholarships, and for marketing these often well-paying careers. Child care administrators and occupational therapists, two examples Reeves cites, respectively earned on average $70,000 and $72,000 in 2019.

The people struggling the most economically are more likely to be men. An astounding one-third of men with only a high school diploma (approximately 5 million men) are out of the labor force.

One of the most discussed policy proposals in the book deals with educational gaps, which Reeves wants to address largely by “redshirting boys,” or delaying their start in kindergarten by a year. It’s not that young boys are less able than their female counterparts, but rather that they cognitively develop at a different pace, about two years slower than girls. For Reeves, giving boys the “gift” of an extra year before starting school “recognizes natural sex differences, especially the fact that boys are at a developmental disadvantage to girls at critical points in their schooling.”

Reeves’s reasoning reflects an important aspect of his approach: he acknowledges the importance of biology, and thinks that understanding biological factors should moderate a tendency, frequently seen on today’s left, to confuse equality with sameness. After examining data on men’s and women’s different career interests and outcomes, for example, Reeves concludes that we should at the very least consider that biology and “informed personal agency” play some role in occupational choices. He rejects attributing all gender gaps to sexism, or expecting perfect 50–50 representation in all fields.

People of different political stripes can debate the scope and specifics of both the HEAL movement and redshirting boys, among other proposals in Of Boys and Men, but Reeves leaves the possibility of fruitful deliberation very much open. He helpfully frames his discussion of education and jobs so that potential disagreements will be about means, rather than fundamental ends.

But the same can’t be said about the third aspect of the male malaise Reeves identifies: the cultural status of fatherhood.

Fatherhood without Marriage?

Reeves recognizes a sense of aimlessness has taken hold of many men’s most personal relationships: between men and women, and between fathers and children. But he primarily wants to address the latter problem, and to do so by envisioning fatherhood as an independent institution, considered separately from marriage. We should address and improve relationships between fathers and children first, irrespective of whether fathers are married to their kids’ mothers. Our safety net should expect more than mere economic support from fathers—particularly among noncustodial parents—and reward them for involvement in their kids’ lives. In a nutshell, our culture and policy should reconcile themselves with the reality that we live in “a world where mothers don’t need men, but children still need their dads.”

Why doesn’t Reeves concurrently advance a marital renewal? For one thing, he regards the traditional model of marriage as too rigidly predicated on the expectation of a male breadwinner, and by extension on the economic dependence of women. From it flows a notion of fatherhood that may have encouraged family formation in the past, but that is now “unfit for a world of gender equality.” The decline of marriage poses problems, but it’s largely indicative of positive gains in autonomy for women, in his view.

Reeves emphasizes that many unmarried, nonresidential fathers are very involved in their kids’ lives. Black fathers, for example—44 percent of whom are nonresidential—are more likely than white nonresidential fathers to help around the house, take kids to activities, and be generally present, according to one study he cites. Reeves argues that our cultural expectations of fatherhood “urgently need an update, to become more focused on direct relationships with children” (emphasis added). Since about 40 percent of births in the United States take place outside of marriage, he concludes that insisting on a model that assumes an indissoluble link between fatherhood and marriage is just anachronistic.

But Reeves doesn’t fully reckon with the gravity of divorcing fatherhood from marriage. Chapter 12 of Of Boys and Men, which Reeves dedicates to his independent fatherhood proposal, advances particular policies to support “direct” fatherhood unmediated by marriage, from paid parental leave to child support reforms, to encouraging father-friendly jobs. But he spends surprisingly little time directly arguing against the empirical and philosophical case for fatherhood within marriage as distinctly positive.

For example, Reeves writes that “there is no residency requirement for good fatherhood. The relationship is what matters.” Fair enough. But which model—fatherhood within marriage or nonresidential fatherhood—tends to facilitate more of the positive interactions needed to build healthy relationships between fathers and children? In general, the one where more of those interactions can potentially take place. A study by Penn State sociologist Paul Amato suggested this, reporting that from 1976 to 2002, 29 percent of nonresident fathers had no contact with their kids in the previous year, while only 31 percent had weekly contact.

Which model—fatherhood within marriage or nonresidential fatherhood—tends to facilitate more of the positive interactions needed to build healthy relationships between fathers and children?

In fact, contact with their biological father plays a positive role in advancing the two other major concerns Reeves has for boys: work and education. A 2022 report from the Institute for Family Studies found that “[y]oung men who grew up with their biological father are more than twice as likely to graduate college by their late 20s, compared to those raised in families without their biological father (35% vs. 14%).” According to the Census Bureau, approximately 62 percent of children lived with their biological parents in 2019, and 59 percent lived with married biological parents. In other words, growing up with a biological father is deeply intertwined with growing up with a married father—there are very few cohabitating biological or single biological fathers.

Beyond social science, there’s also a conceptual issue at the heart of Reeves’s proposal. It’s undeniable that many working mothers don’t need men in the same way past generations did—if what we mean by “need” is economic support. But it’s also very clear that mothers do need men. Without men, well, they wouldn’t be mothers (and vice versa) for the very simple yet profound fact that the sexes need each other in order to fulfill their biological end. This is more than a semantic trick—it’s a recognition that mutual dependence is at the heart of our biology. At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, men and women could not exist without each other—and that realization should caution us against overemphasizing independence.

Moreover, shouldn’t fatherhood also entail modeling what lasting commitment to a spouse looks like? Reeves is right to stress that fatherhood should mean more than just economic support, but he misses the fact that prospects for decoupling marriage from fatherhood are similarly discouraging in this regard. In a study by the late Princeton sociologist Sara McLanahan, 80 percent of unmarried parents were in a romantic relationship (with each other) at time of the birth of their child. But here’s how McLanahan summarized her five-year follow-up with them:

Despite their “high hopes,” most unmarried parents were unable to maintain stable unions. Only 15 percent of all our unmarried couples were married at the time of the five-year interview, and only a third were still romantically involved (Recall that over 80 percent of parents were romantically involved at birth.) Among couples who were cohabitating at birth, the picture was somewhat better: after five years, 26 percent were married to each other and another 26 percent were living together.

In divorcing fatherhood from marriage so hastily, Reeves misses an opportunity to consider why reimagining marriage is a key aspect of reinvigorating fatherhood as well. It’s the biggest drawback of Of Boys and Men.

Nevertheless, Reeves’s proposal has clearly opened a door to fruitful further debate. His case for direct fatherhood should temper a traditionalist reflex to assume that nonresidence is equivalent to abandonment—there are clearly many nontraditional, not-married, or separated fathers who embody dedication to their children. But if engaged fatherhood is so empirically and conceptually intertwined with marriage, then we would lose key aspects of both by separating them. We shouldn’t idealize marriage or how it affects fatherhood, but we shouldn’t hastily decouple marriage and fatherhood either.

Successfully reimagining marriage and fatherhood will probably even entail letting go of some of the overly rigid gender roles that Reeves criticizes in Of Boys and Men: more female breadwinners and paternal homemakers, as well as various policies and workplace arrangements to support the parent–child bond are all likely to be a part of the future of the family. But so should giving boys and men not just the tools to excel at school and work, but the habits and vocabulary to strive toward commitment, dedication, and love in the most personal dimensions of their lives.

If engaged fatherhood is so empirically and conceptually intertwined with marriage, then we would lose key aspects of both by separating them. We shouldn’t idealize marriage or how it affects fatherhood, but we shouldn’t hastily decouple marriage and fatherhood either.

Improving the Debate

Of Boys and Men is a book about men, written by a man, claiming that our culture doesn’t take men’s problems seriously. In the wrong hands, it would have been the latest entry in a seemingly incessant culture war, a callback to the silliness of the Gillette controversy. Yet it has been a resounding mainstream success. In matters of gender and sex, some might believe it’s impossible for there to be any interest in men’s issues across the ideological spectrum. The success of Of Boys and Men suggests that’s not the case.

Of Boys and Men has a point of view, but Reeves doesn’t close off the possibility of exchange or criticism by making a caricature of his opponents. This is the sort of book that not only exposes an often ignored issue, but elevates the quality of our conversations about it, even amid disagreement. That is perhaps its most impressive feat.

The new documentary “No Way Back: The Reality of Gender-Affirming Care” criticizes transgender ideology from a self-described “liberal, west coast Democrat” perspective. Despite facing significant resistance from trans activists, it has been making an impact.

The film will be showing in select theaters across the country during a one-day AMC Theatres Special Event on Wednesday, June 21st at 4:30 and 7:30 pm. It will be available online and on DVD starting July 2nd.

Below, Joshua Pauling interviews producer Vera Lindner.

Joshua Pauling (JP): Thanks for taking the time to discuss your new documentary. It really is a powerful depiction of what is happening to people when transgender ideology takes over. I especially found the detransitioners’ stories compelling. The story you tell throughout is decidedly reasonable and anchored to reality. Kudos to you all for producing such a thorough and moving documentary on such an important and controversial topic. And much respect for being willing to say hard but true things in the documentary.

How has the response been to the film thus far?

Vera Lindner (VL): We’ve received tons of gratitude, tears, and donations. The most humbling has been the resonance the film created in suffering parents. I wept many times reading grateful, heartbreaking messages from parents. People are hungry, culturally speaking, and are embracing our film as truth and facts, and a “nuanced, compassionate, deeply researched” project.

JP: That is great to hear, and interesting that there has been an overwhelming response from parents. Parents are frequently the forgotten victims of this ideology.

How has the film been doing when it comes to numbers of views and reach?

VL: Since February 18th, the film has been viewed 40,000 times on Vimeo, after it was shut down in its first week and then reinstated due to publicity and pressure from concerned citizens. Many bootlegged copies have proliferated on Odysee, Rumble, and such, so probably 30,000 more views there as well. After we put it on Vimeo on Demand in mid-April, it’s getting purchased about 50 times a day. Our objective is the widest possible reach.

Since February 18th, the film has been viewed 40,000 times on Vimeo, after it was shut down in its first week and then reinstated due to publicity and pressure from concerned citizens.

JP: Sad to say, I’m not surprised that it was shut down within a few days. Can you explain more about how such a thing happens? In what ways has it been blocked or throttled?

VL: Vimeo blocked it on the third day due to activists’ doing a “blitz” pressure campaign on Vimeo. Then they reinstated it, after news articles and public pressure. Our private screening event in Austin was canceled due to “blitz” pressure on the venue (300 phone calls by activists in two days). These experiences help us refine our marketing strategy.

JP: I guess that shows the power of public pressure, from either side. You know you’ve touched a nerve when the response has been both so positive as to receive countless heartfelt letters from people, and so harsh that activists want it canceled.

What do you see as next steps in turning the tide on this topic as a society? What comes after raising awareness through a documentary like this?

VL: Our objective was to focus on the medical harm and regret of experimental treatments. All studies point to the fact that regret peaks around eight to eleven years later. Yet the message of the activists toward the detransitioners is, “It didn’t work for you, you freak, but other people are happy with their medicalization.”

Our expectation is that conversations about the long-term ramifications of this medical protocol will start. We need to talk not only about how individuals are affected, but the society as a whole. Wrong-sex hormone treatment and puberty blockers lead to serious health complications that could lead to lifelong disability, chronic pain, osteoporosis, cardiac events, worsening mental health. SRSs (sex-reassignment surgeries) cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. These are not just one individual’s personal issues.

The economics of our health insurance will be impacted. The ability of these people to be contributing members of society will be impacted profoundly. The Reuters investigation from November 2022 stated that there are 18,000 U.S. children currently on puberty blockers and 122,000 kids diagnosed with gender dysphoria (and this is only via public insurance data, so likely an undercount). These all are future patients with musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and mental illnesses for a lifetime. A hysterectomy at twenty-one can lead to early dementia, early menopause, and collapse of the pelvic floor organs.

The economics of our health insurance will be impacted. The ability of these people to be contributing members of society will be impacted profoundly.

I don’t yet see conversations about the long-term health implications of “gender-affirming care,” particularly in relation to how insurance, the labor force, interpersonal relationships, and future offspring will be affected. Everyone wants to be affirmed now and medicalized now. But there are lifelong implications to experimental medicine: autoimmune illnesses, cancers, etc. Sexual dysfunction and anorgasmia have real implications on dating, romantic life, and partnering up. A few people are talking about this on NSFW posts on Reddit.

JP: It’s interesting how speaking out against trans ideology and gender-affirming care creates some unlikely alliances across the political and religious spectrum. What do you see as the potentials and pitfalls of such alliances?

VL: We align with people who are pro-reality, who respect core community values such as truth and honesty, and who see the human being as a whole: body and soul. There is no metaphysical “gendered soul” separate from the body. Teaching body dissociation to kids (“born in the wrong body”) has led to a tidal wave of self-hatred, body dysmorphia, depression, anxiety, and self-harm. We are our bodies, and we are part of the biosphere. We respect nature and the body’s own intricate biochemical mechanism for self-regulation, the endocrine system. We believe that humans cannot and should not try to “play God.” We are students of history and know that radical attempts to re-engineer human society according to someone’s outrageous vision (read Martine Rothblatt’s The Apartheid of Sex) have led to enormous human cataclysms (communism, Chinese cultural revolution).

We are our bodies, and we are part of the biosphere. We respect nature and the body’s own intricate biochemical mechanism for self-regulation, the endocrine system.

JP: Well, then count me a realist, too! Funny you use the term pro-reality. I’ve written similarly about the possibility of realist alliances. While this makes for some improbable pairings, there can be agreement on the importance of fact-based objective reality and the givenness of the human body.

Realists can agree that the world is an objective reality with inherent meaning, in which humans are situated as embodied, contingent beings. Such realists, whether conservative, moderate, or progressive, might have more in common with each other on understanding reality and humanity than some on their “own side” whom I call constructivists: those who see the world as a conglomeration of relative meanings, subjectively experienced by autonomous, self-determining beings, who construct their own truth and identity based on internal feelings.

But I do have a related question on this point—a bit of respectful pushback, if I may.

Your pro-reality position seems to have implications beyond just the transgender question. Can one consistently oppose the extremes of gender-affirming care while upholding the rest of the LGB revolution? If our male and female bodies matter, and their inherent design and ordering toward each other mean something, then doesn’t that raise some questions about the sexual revolution more broadly?

As we see the continued deleterious effects on human flourishing unfold as thousands of years of wisdom and common sense regarding sex and sexuality are jettisoned, there are both religious and non-religious thinkers raising this question, though some go farther than others. I think, for example, of Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, Christine Emba’s Rethinking Sex, Mary Harrington’s Feminism Against Progress, and Erika Bachiochi’s “Sex-Realist Feminism.” An enlightening panel discussion with many of these thinkers was co-hosted by Public Discourse earlier this year. When the real human body is considered, its holistic structure as male or female is clearly ordered and designed to unite with its complement.

If our male and female bodies matter, and their inherent design and ordering towards each other mean something, then doesn’t that raise some questions about the sexual revolution more broadly?

How does this reality relate to the rest of the sexual revolution? If one argues that individuals should be able to express themselves sexually and fulfill their desires with no external limits beyond human desire or will, how does one justify saying that transgenderism is off-limits?

VL: I will answer the question, but I need to say that this is my personal opinion. I’m fifty-five and have worked in entertainment for more than thirty years, and in Hollywood for twenty-five years. The entertainment industry attracts LGBT people, so I’ve hired, mentored, befriended, and promoted LGBT and gender-non-conforming people every day of my career. I believe that being gay or lesbian is how these people were born. Some were affected by their circumstances, as well, but in general I believe that homosexuality is innate, inborn, and has existed for millennia. There were a handful of “classic” transsexual women as well. I have three close friends who transitioned in their late forties.

But the explosion we are seeing now is different. A 4,000-percent increase of teenage girls identifying as trans? This is unprecedented. Mostly these are autistic, traumatized, mentally ill teens who seek to belong, who wish to escape their traumatized brains and bodies, who have been bullied relentlessly (“dyke,” “fag,” “freak”) and now seek a “mark of distinction” that will elevate their social status. Instead of being offered therapy, deep understanding, and compassion for their actual traumas, they are being ushered toward testosterone, mastectomies, and hysterectomies. This is not health care. The tidal wave of regret is coming, because these adolescents were never transsexual to begin with. Many of them are lesbians or gay boys who have internalized so much homophobia and bullying that they would rather escape all of it and become someone different than deal with it.

This is what we want to address. Kids explore identities. This is a natural process of discovering who they are. Medicalizing this exploration cements this exploration they were doing when they were teens. Life is long, and one goes through many phases and many “identities.” To be “cemented” for a lifetime in the decision you made as a distressed sixteen-year-old to amputate healthy sex organs does not make sense.

JP: The rise in the rate of transgender identification is indeed stunning, as is the stark increase in the percentage of Gen-Zers who identify as LGBT. What those trends portend is a live question, as are the varied possible causes. And as you say, there is a tidal wave of regret building, from those who have been pushed toward gender transition. We will all need to make special effort to love and care for them.

You’ve been so gracious with your time. As we conclude, are there any other comments you’d like to share with our readers?

VL: Find a theater near you to attend the theatrical one-day premier on June 21st. Then the movie will become available online and via DVD on July 2nd. Watch the documentary and pass it on to all in your circles!

And ask commonsense humanistic questions:

– Can adults make decisions on behalf of kids that will forever change the path of the kids’ lives?

– Is it worth it to ruin one’s health in the name of a belief system?

– Is what you are reading in academic medical research based on evidence, or pseudo-science?

– If humans have been going through puberty for millennia, who are we to mess with that now?

– Is puberty a disease?

JP: Thank you for your work on this vital issue. I hope this documentary continues to make an impact. And realists unite!

If you follow college football, you probably heard that Glenn “Shemy” Schembechler was recently forced to resign from his post as assistant director of football recruiting at University of Michigan shortly after he was hired. This occurred after news emerged that he had liked numerous racist tweets. Glenn is the son of “legendary” Bo Schembechler, who won 13 Big Ten championships as coach of UM football from 1969–1989. Apparently it wasn’t enough to prevent Glenn’s hiring that he denied that his brother Matt had told their father that UM team doctor Robert Anderson had sexually assaulted him during a physical exam. Glenn insisted that “Bo would have done something. … Bo would have fired him.” Yet law firm WilmerHale had already issued a report confirming that Bo had failed to take action against Anderson after receiving multiple complaints from victims about Anderson’s abuse. Matt has testified that his father even protected Anderson’s job after Athletic Director Don Canham was ready to fire him.

Women are often asked why they didn’t scream when they were being raped, or why they didn’t immediately report the rape to the police, as if these inactions are evidence that the rape never happened. This post is about why Bo didn’t scream after his own son complained of sexual victimization by his team’s doctor. The answer offers insight into the political psychology of patriarchy, which is deeply wrapped up in the kind of denial of reality that Glenn expressed, and that Bo enforced. It also illuminates why women don’t scream when they are assaulted.

Glenn’s reasoning in defense of his father expresses the self-understanding of those committed to a certain form of patriarchal ideology. In the U.S., college football is the premier sport in which coaches are represented as experts in training up young men to be real men, exemplars of a certain version of estimable masculinity. In this version, plays for domination must take place on the field within the rules of the game, and real manhood comes with responsibilities. The syllogism implicit in Glenn’s reasoning is clear: Real men protect those for whom they are responsible. Bo was a real man. So, if Bo knew that his son or his athletes–those for whom he is responsible–were being harmed, he would have protected them by firing Dr. Anderson.

The heartbreaking and deeply disturbing testimony of Matt Schembechler, along with two of Bo’s former football players, Daniel Kwiatkowski, and Gilvanni Johnson, tells a very different story about how Bo understood the demands of real manhood. When 10-year-old Matt told his father that Anderson had sexually assaulted him, Bo got angry with him and punched him in the chest. When Kwiatkowski complained that Anderson had digitally raped him, Bo told him to “toughen up.” When Johnson complained of the same abuse, Bo put him “in the doghouse,” suddenly started demeaning his athletic performance, and barred him from playing basketball although he was recruited for both sports.

“Bo knew, everybody knew,” said Kwiatkowski. Players joked about seeing “Dr. Anal” to Johnson. Coaches would threaten to send players to be examined by Anderson if they didn’t work harder. Victims stayed silent out of fear of losing their scholarships or chances to play football.

Bo didn’t appear to be angry at Anderson. He was angry at his son and his players for complaining. He was teaching them a different set of rules for real manhood from the official patriarchal ideology: 1. Real men don’t get raped. More generally, they don’t get humiliated by others. 2. If they do get humiliated, they had better not whine about it. 3. Instead, they should “toughen up,” which is to say, bear up under the abuse, put up with it, act like it didn’t happen. In other words, submit silently.

These are bullies’ rules–the rules for real manhood that protect bullies at the expense of the subordinates they are ostensibly supposed to protect. They are reflected in the stiff upper lip of England’s elite boarding schools, notorious for enabling bullies to terrorize other students. In the code of Southern honor satirized by Mark Twain in Pudd’nhead Wilson, where it was unmanly to settle disputes in court rather than duking it out. In the 2016 GOP Presidential primary debates, which were all about who could prove they were the bigger bully. In Mike Pence’s refusal until recently to blame Trump for Jan. 6, even though Trump had repeatedly humiliated him and set a mob out to lynch him for refusing to overturn the election.

Yet this explanation doesn’t quite answer the question of why Bo didn’t just fire Anderson from his position as team doctor, or let Athletic Director Don Canham do so, when Matt’s mother complained to Canham, taking up the duty to protect that Bo abandoned. Why did Bo put up with his son and his team being abused? To understand this, we need to dive deeper into the relationship between humiliation and shame.

People feel humiliated when someone else forces them into an undignified position or treats them as someone who doesn’t count, as contemptible or even beneath contempt. Humiliation is a response to how others treat oneself. People feel shame when they fail to measure up to social standards of esteem that they have internalized. One might feel ashamed for “allowing” another person to humiliate oneself, even if one had no way to avoid it. In that case, humiliation precedes shame. But there are many other causes of shame not predicated on humiliation.

Everyone agrees that a characteristic response to shame is to want to hide from the gaze of others. There are at least two characteristic responses to humiliation. (1) Getting even: restoring oneself to a position of (at least) equality with respect to the bullying party, often by means of violence. It took social change for lawsuits to provide a respectable nonviolent alternative. (2) Submission: like the dog who loses a fight and slinks away, tail between its legs.

According to the bullies’ patriarchal rules of real manhood, one’s manhood can be demeaned and one can thereby be humiliated by the humiliation of associates under one’s authority. This is explicit in honor cultures, where the honor of men is embodied in the sexual purity of their female relatives. A man can humiliate another man by raping or seducing his wife, daughter, sister, or niece. Female relatives humiliate the men responsible for them by choosing to have sex outside of an approved marriage. Others mock men for failing to protect and control their female relatives. Manly honor is thus deeply wrapped up in totalitarian control over their female relatives’ sexuality.