George Orwell, review of Mein Kampf (1940):

Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all “progressive” thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won’t do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades. However they may be as economic theories, Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life. The same is probably true of Stalin’s militarised version of Socialism. All three of the great dictators have enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples. Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a more grudging way, have said to people “I offer you a good time,” Hitler has said to them “I offer you struggle, danger and death,” and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet. Perhaps later on they will get sick of it and change their minds, as at the end of the last war. After a few years of slaughter and starvation “Greatest happiness of the greatest number” is a good slogan, but at this moment “Better an end with horror than a horror without end” is a winner. Now that we are fighting against the man who coined it, we ought not to underrate its emotional appeal.

Dear Fellow Signers of the Declaration of Independence:

Now that our noble document is complete, it is time to address the elephant in the room: my name is much bigger than everyone else’s. I’ll be the first to admit that it is absolutely massive. Yet I must also speak this self-evident truth: it is not entirely my fault.

The fact is I thought we were all doing big signatures. That’s what I was told. Do none of you remember Thomas Jefferson—hopped up on parchment fumes and cheap barleywine—running around telling everyone our “sigs” had to be “freakin’ huge”? Then I go first, and everybody bursts out laughing like I did something foolish.

I hereby call on my brethren of the Second Continental Congress—those who I know to be defenders of liberty, progress, and the values of the Enlightenment, to which we are all fan-boyishly devoted for some reason—to publicly stand up and say everybody told John Hancock we were doing big sigs.

Of late—in taverns and shops, on the streets, and in drawing rooms—I have overheard people asking one another for their “John Hancocks.” Like that’s just a thing now? I do not want my name to be a thing. Do you want your names to be things, my Founding Brothers-in-Arms? I say to you, Pat Henry—remember that night you, me, and Sammy Adams got totally wasted? Do you want “staggering into the town square and defiling the steps of the courthouse” henceforth to be known as “Patrick Henrying”? I thought not.

Let me be fully honest with you, brothers. The night of the signing, I did have too much wine. I meant to go big with the signature, but I went overboard. Trembling from the drink, my hand slipped, forcing me into an enormous “J.” And then it was off to the races. Each attempt to correct my mistake only made it worse, and eventually, I just had to commit.

We had options, though. We could have pasted on a few extra inches of parchment to fit all the bigger signatures or made a new version entirely, but James Madison had to return to Virginia to carve soap or something, so everybody just left. I’ve said sorry. Shouldn’t that be enough? Isn’t that why we’re building this whole system—so that people like us can do whatever we want without consequence?

I know now that I should not have told all of Boston that I wrote the Declaration of Independence by myself. That was wrong. But I got so many free drinks. I am most ashamed to report that one evening in Cambridge, I imbibed so much that I Patrick Henried all over John Harvard’s little schoolhouse.

Fine, you want the full confession? Better you hear it from me. Even though it was an accident, I saw an opportunity to make “Big John” a thing. I was planning Big John business ventures of all kinds, primarily Big John-branded whale oil candles. I am now on the hook for literally tens of thousands of candles. If anyone would like to purchase a few dozen cases, please let me know posthaste.

I understand that history will wonder about me: Did he have a massive ego? Shaky hands? A penchant for the drink? As I’ve addressed in this letter, yes, yes, and ohhh yeahhh. I own my faults, and I humbly ask you to forgive me. For if you don’t, I will have no choice but to make common cause with the British and bring vengeance down upon your heads. Especially you, Jefferson.

As a show of good faith and to rectify my error, I would like each one of you to sign this letter next to my very appropriately-sized signature and append it to the official Declaration of Independence to demonstrate for posterity that I, John Hancock, do know how to sign my name regular-style.

With ardent patriotism and deep regret,

Fuck.

“Streaming” [verb / strEEm-ing]: Crossing a medium-sized body of water in short trousers to rescue one’s horse and carriage from sudden peril.

“Bop” [noun / bäp]: The sound of George Washington’s hand-crafted Masonic gavel landing on a ceremonial cornerstone.

“Cheugy” [verb / chew-ghee]: The act of using one’s wooden teeth to thoroughly masticate turtle soup.

“Taylor Swift” [noun / TAY-lor SWIH-ft]: A tradesperson who can alter silken blouses at an exceptionally quick pace.

“Bougee” [noun / BOO-jee]: The name of Thomas Jefferson’s childhood kitten.

“Clapback” [noun / klap-bAk]: An unfavorable condition for a racehorse’s spine.

“Ded” [adjective / DEH-d]: Obituary delivered via illiterate messenger.

“G.O.A.T.” [noun / GOH-t]: A delicious hearty stew.

“Texting” [verb / tEk-st-ING]: The act of carrying flat wooden printing platen across town in large satchels typically made from wool and miscellaneous hides.

“Stan” [noun / STAN]: James Madison’s personal errand boy.

“Lit” [adjective / LIT]: Candlelight used to brighten one’s living quarters in an effort to ward off complete and total darkness.

“Dank” [adjective / DAHN-keh]: Damp/musty conditions, typically used to describe wine cellars, houses of repentance, and Benjamin Franklin’s living room.

“Fire” [noun / fIEUH]: Inexorable natural disaster.

“Spilling the Tea” [expression / SPIL-ing thuh TEE]: An extreme act of American mercantile protest.

“Wig” [noun / WHIG]: 1. A delightful white hair piece used to cover childhood quill scars and uneven balding. 2. A frightening threat to democracy.

“Big Yikes” [expression / BIG YYKS]: Smallpox.

Some facts:

I’m here for the tiny fraction of 1% of Americans who can grasp that the interpretation of law, including the Constitution itself, is very difficult, especially when you have more than 200 years of precedent to reckon with. Often precedents are inconsistent with one another; previous Supreme Court decisions can be unclear, some of them right from the beginning and others in light of social and political developments that came after they were issued; very few cases make it to the Supreme Court if there are not defensible claims on both sides — if they were easy, they’d have been settled in lower courts, and SCOTUS wouldn’t have agreed to hear them at all.

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College is a fascinating case, and the opinions, concurrences, and dissents — all 237 pages of them — provide an extraordinary education in the social as well as the legal consequences of hundreds of years of American racism, and in the enormous complications introduced into our system by the arrival in America of large numbers of people who are neither white nor black.

(I’m setting aside, for the moment, Native Americans, who have been a dramatically special case from the beginning — as can be seen in SCOTUS cases from this very term, most notably Haaland v. Brackeen. See this NYT piece on Justice Gorsuch’s passionate commitment to Native American rights.)

I don’t know how you could read the Harvard/UNC case and think that these matters are easily resolved. Those who can’t be bothered to read the details of the case may well find it easy, but then, most issues on most subjects are easy to the uninformed. This is one of those cases in which every argument (opinion, concurrence, dissent) seems convincing — when read in isolation from the others.

I’m working my way through the whole thing, and already have a thousand thoughts. I may report later. But in the meantime, I would just encourage those of you who haven’t read the case, and especially those of you who won’t read the case, to give up the luxury of having an opinion about it.

Today is the pub day for the longest essay I’ve ever published: “The Far Invisible: Thomas Pynchon as America’s Theologian.” (It’s paywalled, but of course you’ll want to subscribe.)

How seriously do I mean my claim that Pynchon is a theologian? Is it a substantive claim or a provocation? I mean it pretty seriously.

Here’s how I would put it: Emmanuel Levinas famously argued that “ethics is first philosophy” – it is in ethics that philosophy should and indeed must begin. So, what is first theology? The answer to that question might not always be the same; it might vary by time and place. So I say that in our moment suspicion is first theology – a double suspicion, first that the rulers of this world are not the beneficent guides that they claim to be, and second that the world they rule is not the sum of things. (As Wendell Berry puts it, there are two economies, the market economy and the Kingdom of God.) Such suspicion is thus, in an endless doubling, skeptical and hopeful. These are also the two modes of prophecy, it seems to me.

This first theology is not, and cannot be, the whole of theology; but even Aquinas and Barth could not do the whole of theology, and we shouldn’t demand it of any theologian. I argue that Pynchon is our best guide to where and how theology in our time must begin; and one way to think of the task of theology for Christians is to ask what theological project should follow the one that Pynchon has inaugurated.

For those of you who are new to Pynchon — especially those who are intimidated by the thought of reading him — I’ve written an introductory guide just for you.

Finally (for now), just a couple of connections: I might want to put Pynchon in conversation with

Much more to do here!

“Justice Samuel Alito took luxury fishing vacation with GOP billionaire who later had cases before the court.” — ProPublica

“The Supreme Court on Thursday struck down affirmative action programs at the University of North Carolina and Harvard in a major victory for conservative activists, ending the systematic consideration of race in the admissions process.” — NBC News

We, the conservative justices of the Supreme Court, have ruled against Harvard and UNC, striking down affirmative action for college admissions across the country. For a detailed explanation of our ruling, feel free to read the court’s majority decision. But in a nutshell, we believe the only people who should ever get extra consideration are those who invite you to hang out on their boats.

You see, it came down to a matter of fairness. Getting into college should be based purely on merit—getting good grades, scoring highly on the SAT, writing a compelling essay, and participating in extracurriculars that speak to your interests. And if one of those interests happens to be sailing, and your family happens to have a 120-foot sailing yacht, and you happen to go on an eight-day pleasure cruise in the Mediterranean the summer before your senior year of high school, and your dad happens to invite the head of admissions at Dartmouth on that trip, we’d see absolutely no problem with that. Just as long as you keep the conversation to nautical topics like, “What are some of your favorite knots?” Or “Spinnakers, am I right?” Or “Say, how competitive is the Dartmouth sailing team, anyhow?”

As we deliberated on the Harvard case, we saw two major sources of inequity in the admissions process:

To determine which was a bigger ethical issue, we asked ourselves a simple question: In which of these two groups are you more likely to own a catamaran? After considering that, the majority opinion practically wrote itself.

The liberal justices argued that rolling back affirmative action would undo decades of progress designed to right the wrongs of systemic inequality. But we don’t believe in being on the “right” side of this issue. We believe in being on the “starboard” side of this issue—the side that favors folks who invite us over for cocktails on the starboard sides of their boats. Which, incidentally, is the right side of the boat, so we think that counts.

Regarding the merits of the decision, some legal scholars felt it was dubious to cite the 14th Amendment, which the court had previously used to argue the exact opposite ruling in favor of affirmative action decades ago. But not one of those scholars invited us on a deep-sea fishing trip to Alaska, or an island-hopping jaunt in the Caribbean, or even a day sail on the Potomac. We might have been more sympathetic to their counterpoints had they thought to do that.

It’s also worth noting that, while the 14th Amendment says many things about equal protection and due process, it says absolutely nothing about boats, or at what point a “boat trip with friends” becomes a “quid pro quo.” Nobody needs a reason to invite you on their boat. Besides, who wouldn’t want to spend an afternoon with Clarence Thomas simply for the divine pleasure of his company?

For those who say the college experience is enriched by having classmates of different backgrounds and perspectives, we can say with certainty that the college experience is also enriched by knowing more people who own megayachts. Depending on how you define “enrich,” of course.

And if you do eventually strike it rich and want to bring us along for a sail, we’d be happy to hop on board. Better yet, hand us a mai tai and one of those captain’s hats with a little anchor on it, and you might find we’ll be “on board” with just about anything.

The best thing you are likely to read about the Supreme Court affirmative action decision — or rather the response to it — is Freddie’s take. Two points strike me as especially important: first, that the whole kerfuffle is a distraction from any actually meaningful racial politics in this country, since a candidate who has to go to Columbia or Amherst rather than Harvard is not exactly a victim; and second, that there’s a massive media freakout about this because so many people in our media are the products of elite universities. Several decades ago, when most journalists attended mediocre universities or, often enough, were not even college educated, we would have had a chance to have this story like this presented with some fresh, clear, well-seasoned perspective. But our journalists haven’t had any of that commodity on hand for a long, long time.

I received an unexpected check in the mail from the U.S. government. I wasn’t sure what it was for. At first I figured maybe it was a tax refund. But in the memo it said “reparations for being crippled. “

I don’t recall demanding that the government pay me reparations for being crippled. And I don’t recall anyone else ever demanding that either. But sometimes the government does nice things out of the blue just for the hell of it. That’s how we got the Americans with Disabilities Act. Congress just woke up one morning feeling particularly chipper and it said to itself, “I think I’ll surprise the cripples by giving them this law, just to remind them how much we love them. They really deserve it. I can’t wait to see the look of delight on their sad little faces!” I figure if the government wants to give me free money, who the hell am I to say no? So I cashed the check. I considered it to be my patriotic duty.

There was a letter included in the envelope with the check. It said, “Dear Mike, This is the U.S. Government writing to say we’re sorry you’re crippled. Please accept the enclosed check as a token of our condolences. Consider this our way of trying to help you relieve your pain and suffering.”

So I took all the cash and flew to Vegas. And besides what I spent on stuff like airfare and hotel, I blew all the rest of my reparations on snorting lines of cocaine off the bare bellies of exotic dancers. Why not? After all, the purpose of the money was to relieve the pain and suffering I’ve endured because I’m crippled.

And now I’m back home and back to being broke ass. I think the whole thing was an experiment. Sometimes governments use cripples as guinea pigs. The Nazis had a campaign of trying to exterminate cripples so they could be more efficient when it became time to try to exterminate the Jews.

Maybe the government started out by sending cripples reparations just to see what would happen. Because a lot of people say that if the government gives cash directly to poor people they’ll just take it and blow it all.

So maybe, based on what I did, the next time the government pays some other group of people reparations, in order to keep them was squandering it frivolously, they’ll send them a gift card from Home Depot or something.

(Please support Smart Ass Cripple and help us keep going. Just click below to contribute.)

https://www.paypal.me/smartasscripple?fbclid=IwAR2qrql-UFH19OepgeaCG4WmblyNylb27k2q8eYxXHH-nvFX30Mk2fJx9uI

I reject the widespread idea that Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy is based on an « ontology of difference ». The only book where he seems to propound such an ontology is in DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION, and in the very next book LOGIC OF SENSE « difference » plays next to no role. « Difference » is a mask for multiplicity.

This idea of difference as being only one (and temporary) instantantiation of multiplicity is explicated in many places on my blog and in my various articles, but it can be found specifically set out here:

https://www.academia.edu/11652059/LARUELLE_AND_DELEUZE_from_difference_to_multiplicity

It would be a mistake to concludee that Deleuze progressed from differentialism to pluralism Guattari’s influence. The conceptual evolution involved is more complex than that.

First we must remark that Deleuze was already a pluralist before DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION (1968), the adhesion to pluralism is very clear in his NIETZSCHE AND PHILOSOPHY (1962), and straight after in LOGIC OF SENSE (1969).

In other words, far from being the key to Deleuze’s thought DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION is the exception, in which Deleuze takes on the « mask » of difference to speak to the contemporary conceptual conjuncture influenced by structuralism and to inflect it towards pluralism.

Note: I put « mask » in scare-quotes because it is more than a disguise on the same conceptual level, as if it were a case of a simple reformulation in the terms of the current vocabulary. It is rather a question of a difference in conceptual level, the ontology of difference is just one instantiation of Deleuze’s pluralist meta-ontology (as is the ontology of desiring machines) which progressively fades away in the chapters of A THOUSAND PLATEAUS, in favour of an ontology of « assemblages ».

My analysis here differs from that set out by Laruelle in his book PHILOSOPHIES OF DIFFERENCE (1986). As I have argued elsewhere on this blog Laruelle comes rather late to the game, propounding post festum his « critical introduction » of philosophies of difference at a moment when all the major thinkers of difference had already long abandoned it.

My second objection to Laruelle on this Deleuzian strand is that he misreads the status of difference in Deleuze, seeing it as the ultimate ontological concept whereas it is the provisional instantiation of a pluralist meta-ontology implemented for intervening in a specific conjuncture, and not to be inflated into a systemic ground.

Deleuze talks about the primacy of multiplicities in all his major works, and about difference in only one. In my reconstruction I call Deleuze’s overarching research programme a pluralist meta-ontology. One of the key traits of pluralism in this sense is diachronicity (the ontology evolves over time and varies over contexts, what Deleuze calls « heterogenesis), another is porosity (the existence of semantic or structural incommensurabilities does not exclude pragmatic interactions, which Deleuze calls « encounters » or « dialogues ».

It is on the basis of this model that I think « difference » is far less important for Deleuze than commonly believed, and that is embodies a low degree of ontological pluralism.

For some wider context, my original paper (from 1980): https://www.academia.edu/42083394/PLURALIST_FLEXI_ONTOLOGY_Deleuze_Lyotard_Serres_Feyerabend_

In 1980 after spending six months in Paris attending Deleuze and Foucault’s seminars, and interviewing Serres and Lyotard, I returned to Sydney and gave a paper synthesising my impressions. In particular I set out my idea of a common meta-ontology of pluralism (that I called « flexi-ontology » at the time, to highlight the diachronic aspect).

It was on the basis of this wider research programme that I elaborated my blog Agent Swarm, and I was pleased to see that Bruno Latour underwent a meta-ontological turn that confirmed my prior hypotheses, asking what is the recommended dose of ontological pluralism?, and distinguishing different levels of dose:

It is interesting in this context to see that Deleuze in 1989 played with the idea of grouping his published works not in chronological order, but rather in an order that we could call « thematic », but that is better described in the light of the distinctions made above between meta-ontology, instantiations, and degrees of ontological pluralism, that in Deleuzian terms we could call degrees of deterritorialisation.

In David Lapoujade’s introduction to DESERT ISLANDS, he cites the divisions that Deleuze envisions for his bibliography:

« I. From Hume to Bergson / II. Classical Studies / III. Nietzschean Studies / IV. Critical and Clinical / V. Esthetics / VI. Cinema Studies / VII. Contemporary Studies / VIII. The Logic of Sense / IX. Anti-Oedipus / X. Difference and Repetition / XI. A Thousand Plateaus »

I am indebted to Alexander Boyd who, citing this classification, posed the question of the logic behind the last four divisions.

In terms of the analysis I have been developing one could see Deleuze’s grouping as corresponding to an order of increasing degrees of deterritorialisation, or of ontological pluralism.

From this point of view, LOGIC OF SENSE is the odd-one-out, as it relies on psychoanalysis (content), series (method), surfaces (metaphysics). ANTI-OEDIPUS constitutes a rupture with all three.

Nonetheless ANTI-OEDIPUS is itself over-engaged in the agon with psychoanalysis and does not make explicit the new image of thought. Deleuze in his new preface to the American edition of DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION makes it clear that over and above the ontology of difference is the « liberation of thought from the images that imprison it ».

This new pluralist practice of thought is described and analysed in Chapter 3 of DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION, but is only partially instantiated in that book. The concrete instantiation of a new image of thought in a variety of domains is finally accomplished in A THOUSAND PLATEAUS.

This is why Deleuze claims that the key chapter in DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION is Chapter Three on the image of thought (and not the chapters on repetition and difference), that this chapter is « the most necessary and the most concrete » and that it serves as the best introduction to the books that follow.

terenceblake

In the beginning, I created the apartment and the lease. Then I said, “Let there be tenant”; and there was tenant. And I saw the tenant and that she had sufficient pay stubs and no criminal record, which was good. For I am the landlord your God, and wish not to reveal my wrath upon our first meeting.

Then I said, “Let there be skylight”; and there was skylight. For it gave the apartment a majestic view of the sun and the stars, which I created too, because, lest you forget, I am the landlord your God, sovereign over all things real estate.

Then I said, “Let there be furnishing.” For the tenant was created in my image and my image alone. Let there be a kitchen backsplash, goblet drapery, TV (with built-in Roku), and a mustard-colored sectional. And it was so. For toiling in the name of home improvement is very good.

And thus, I said to the tenant: “Behold your new palace. I have led you into the land of milk and honey. Eat grapes off my landlord vine. Be fruitful and multiply on your bed fit for a queen!”

But it was not so. For the tenant denied my spoils, sending grievances about the stucco walls having cracks, carping about broken appliance this, gaudy mustard-colored sectional that, blah blah blah.

And the earth shook and trembled because I was so angry. For the landlord your God is a jealous God who exacts vengeance on his tenant adversaries.

But then I thought, “I am the landlord your God; very compassionate, slow to anger, and abounding with love of real estate. Perhaps I should extend an olive branch and see whether the tenant would engage in some fellowship? For I have created infinite Sour Patch Kids and the latest Zelda game on Nintendo Switch.”

But no. My benevolent offer was spurned. And thus, I furiously commanded, “Let the earth bring forth a plague of rats and cockroaches, and let them have dominion over the tenant, lest she forget my almighty power”; and there were so many pests, and it was good. It was very good.

Thus, my tenant begged for mercy. Sobbed like a little newborn. Threatened to take me to the highest court in the land. Something called the “supreme court.” And I said, “Did thou suffer brain injury? For I am the landlord your God, purveyor of justice, lawgiver, and king. Only I can judge the righteous and the wicked.”

Then I considered smiting the tenant right then and there. But, alas, I exercised forbearance. For I am a super-forgiving God who bears no grudges and invariably welcomes the tenant with open arms. And thus, I commanded, “Let the infestation cease, and let my tenant repose on my totally not ugly mustard-colored sectional in peace.”

And on the seventh day, I rested. For all my work had been done. But, alas, a loud noise awakened me from my slumber. When I alighted from my cloud, music and gaiety was abound, undoubtedly the tenant having very loud fellowship without me.

Guests quivered in fear upon my arrival, setting down their wine goblets and Miller High Life. For the landlord your God exudes so much divinity it could kill a small horse. And yet, the tenant failed to bow down before me. She just stood there imbibing her American lager, better known as the “champagne of beers.”

My hands were proverbially tied. The tenant hath violated my statute codified in stone, which clearly stated: “No noise unless to worship the landlord your God.” For I’m only familiar with the entire universe revolving around me.

And thus, I was full of fire and brimstone. And I said to the tenant, “Thou shall not make music nor noise with your instrument! For lest you forget, I own this property and dwell on the top floor with compassion.” To which you could hear a pin drop, all the way to the foothills.

I had no option but to evict the tenant and her followers from my land. Nor would I even deign her very disgusting plea to recoup her security deposit back in full. For upon further inspection, there were actually several cracks in the stucco wall and broken appliances everywhere.

Alas, it is very thankless work to be the landlord your God. For I moved mountains and stars to see the tenant. To draft the lease. To furnish the apartment and charge a very fair rental sum of only four times the going rate. And it was good. It was so good. Until I was betrayed by my most evil tenant.

I’m going to begin by quoting a very long passage from Bleak House, one involving a suitor in the court of Chancery, generally known as “the man from Shropshire,” an oddity who in every session cries out “My Lord!” – hoping to get the attention of the Lord Chancellor; hoping always in vain. His name is Mr. Gridley and Esther Summerson relates an encounter with him:

“Mr. Jarndyce,” he said, “consider my case. As true as there is a heaven above us, this is my case. I am one of two brothers. My father (a farmer) made a will and left his farm and stock and so forth to my mother for her life. After my mother’s death, all was to come to me except a legacy of three hundred pounds that I was then to pay my brother. My mother died. My brother some time afterwards claimed his legacy. I and some of my relations said that he had had a part of it already in board and lodging and some other things. Now mind! That was the question, and nothing else. No one disputed the will; no one disputed anything but whether part of that three hundred pounds had been already paid or not. To settle that question, my brother filing a bill, I was obliged to go into this accursed Chancery; I was forced there because the law forced me and would let me go nowhere else. Seventeen people were made defendants to that simple suit! It first came on after two years. It was then stopped for another two years while the master (may his head rot off!) inquired whether I was my father’s son, about which there was no dispute at all with any mortal creature. He then found out that there were not defendants enough—remember, there were only seventeen as yet!—but that we must have another who had been left out and must begin all over again. The costs at that time — before the thing was begun! — were three times the legacy. My brother would have given up the legacy, and joyful, to escape more costs. My whole estate, left to me in that will of my father’s, has gone in costs. The suit, still undecided, has fallen into rack, and ruin, and despair, with everything else — and here I stand, this day! Now, Mr. Jarndyce, in your suit there are thousands and thousands involved, where in mine there are hundreds. Is mine less hard to bear or is it harder to bear, when my whole living was in it and has been thus shamefully sucked away?”

Mr. Jarndyce said that he condoled with him with all his heart and that he set up no monopoly himself in being unjustly treated by this monstrous system.

“There again!” said Mr. Gridley with no diminution of his rage. “The system! I am told on all hands, it’s the system. I mustn’t look to individuals. It’s the system. I mustn’t go into court and say, ‘My Lord, I beg to know this from you — is this right or wrong? Have you the face to tell me I have received justice and therefore am dismissed?’ My Lord knows nothing of it. He sits there to administer the system. I mustn’t go to Mr. Tulkinghorn, the solicitor in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and say to him when he makes me furious by being so cool and satisfied — as they all do, for I know they gain by it while I lose, don’t I? — I mustn’t say to him, ‘I will have something out of some one for my ruin, by fair means or foul!’ HE is not responsible. It’s the system. But, if I do no violence to any of them, here — I may! I don’t know what may happen if I am carried beyond myself at last! I will accuse the individual workers of that system against me, face to face, before the great eternal bar!”

His passion was fearful. I could not have believed in such rage without seeing it.

Now, please bear Mr. Gridley, and his rage, in mind as I turn to George Orwell’s great essay on Dickens. It’s possibly the finest thing ever written about Dickens – even though it’s often wrong – and is a wonderful illustration of Orwell’s power of inquiring into his own readerly responses. (A topic for another post.)

The first point I want to call attention to is this: Orwell was of course a socialist, a person who believed that British society required radical change; and there were people who saw Dickens as a kind of proto-socialist. This, Orwell points out, is nonsense on stilts. If you want to know what Dickens thinks about revolutionary political movements, just read A Tale of Two Cities. He’s horrified by them.

Orwell then goes on to note that Dickens’s early experiences as a reporter on Parliament seem to have been important for shaping his attitude towards government as a whole: “at the back of his mind there is usually a half-belief that the whole apparatus of government is unnecessary. Parliament is simply Lord Coodle and Sir Thomas Doodle, the Empire is simply Major Bagstock and his Indian servant, the Army is simply Colonel Chowser and Doctor Slammer, the public services are simply Bumble and the Circumlocution Office — and so on and so forth.”

Such a man could never be a socialist. And yet, “Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached.” So what is the nature of this attack?

The truth is that Dickens’s criticism of society is almost exclusively moral. Hence the utter lack of any constructive suggestion anywhere in his work. He attacks the law, parliamentary government, the educational system and so forth, without ever clearly suggesting what he would put in their places. Of course it is not necessarily the business of a novelist, or a satirist, to make constructive suggestions, but the point is that Dickens’s attitude is at bottom not even destructive. There is no clear sign that he wants the existing order to be overthrown, or that he believes it would make very much difference if it were overthrown. For in reality his target is not so much society as ‘human nature’. It would be difficult to point anywhere in his books to a passage suggesting that the economic system is wrong as a system. Nowhere, for instance, does he make any attack on private enterprise or private property. Even in a book like Our Mutual Friend, which turns on the power of corpses to interfere with living people by means of idiotic wills, it does not occur to him to suggest that individuals ought not to have this irresponsible power. Of course one can draw this inference for oneself, and one can draw it again from the remarks about Bounderby’s will at the end of Hard Times, and indeed from the whole of Dickens’s work one can infer the evil of laissez-faire capitalism; but Dickens makes no such inference himself. It is said that Macaulay refused to review Hard Times because he disapproved of its ‘sullen Socialism’. Obviously Macaulay is here using the word ‘Socialism’ in the same sense in which, twenty years ago, a vegetarian meal or a Cubist picture used to be referred to as ‘Bolshevism’. There is not a line in the book that can properly be called Socialistic; indeed, its tendency if anything is pro-capitalist, because its whole moral is that capitalists ought to be kind, not that workers ought to be rebellious. Bounder by is a bullying windbag and Gradgrind has been morally blinded, but if they were better men, the system would work well enough that, all through, is the implication. And so far as social criticism goes, one can never extract much more from Dickens than this, unless one deliberately reads meanings into him. His whole ‘message’ is one that at first glance looks like an enormous platitude: If men would behave decently the world would be decent.

And here’s what I love about Orwell: he says that Dickens’s position “at first glance looks like an enormous platitude” – but he is not content with a first glance. He continues to think about it, and as he does he realizes that Dickens, after all, has a point. This I think is the most extraordinary moment in the essay:

His radicalism is of the vaguest kind, and yet one always knows that it is there. That is the difference between being a moralist and a politician. He has no constructive suggestions, not even a clear grasp of the nature of the society he is attacking, only an emotional perception that something is wrong, all he can finally say is, ‘Behave decently’, which, as I suggested earlier, is not necessarily so shallow as it sounds. Most revolutionaries are potential Tories, because they imagine that everything can be put right by altering the shape of society; once that change is effected, as it sometimes is, they see no need for any other. Dickens has not this kind of mental coarseness. The vagueness of his discontent is the mark of its permanence.

Most revolutionaries are potential Tories – that is, their revolutionary sensibility would erase itself if they could just get Their Boys into power. Once they and people like them are in charge, then they will do anything they can to thwart change. But what that means is: Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. (As I note in this essay, following Ursula K. LeGuin, even an anarchist society would have its petty tyrants.) Most would-be revolutionaries ignore this problem, but “Dickens has not this kind of mental coarseness.” And that’s why he’s vital.

This point takes us back to the man from Shropshire, Mr. Gridley. He will not be calmed by invocations of “the system,” the broken system in which everyone is trapped. The Lord Chancellor is not trapped as he is trapped. The Lord Chancellor is not a victim as he is a victim. The people who enable the system, and profit from it, must be held accountable – or nothing important will change. The salon of politics will only be redecorated. So: “I will accuse the individual workers of that system against me, face to face, before the great eternal bar!”

And this, Orwell suggests, is what the novelist can do, what the novelist can bring before our minds and lay upon our hearts. Some political systems are clearly superior to others; but Dickens understands that whatever political system we build, its chief material will be what Kant called “the crooked timber of humanity,” of which “no straight thing was ever made.” To force us to look at that truth — which, properly understood, will result not in political quietism but a genuine and healthy realism — is what the novelist can do for us. “That is the difference between being a moralist and a politician.” The novelist-as-moralist has the power to drag the individual workers of the system, any system, “before the great eternal bar” — but not God’s bar as such, which is what Mr. Gridley means, but rather, the bar of our readerly witness, our readerly judgment, whoever and whenever we are.

Every spring, the not-quite-pristine waters of Boston Harbor fill with schools of silvery, hand-sized fish known as alewives and blueback herring.

Some of them gather at the mouth of a slow-moving river that winds through one of the most densely populated and heavily industrialized watersheds in America. After spending three or four years in the Atlantic Ocean, the herring have returned to spawn in the freshwater ponds where they were born, at the headwaters of the Mystic River.

In my imagination, the herring hesitate before committing to this last leg of their journey. Do they remember what awaits them?

To reach their spawning grounds seven miles from the harbor, the herring will have to swim past shoals of rusted shopping carts and ancient tires embedded in the toxic muck left by four centuries of human enterprise. Tanneries, shipyards, slaughterhouses, chemical and glue factories, wastewater utilities, scrap yards, power plants — all have used the Mystic as a drainpipe, either deliberately or through neglect.

But today, the water is clean enough to sustain fish and many other kinds of fauna. As they push upstream, the herring may hear the muffled sounds of laughter, bicycle bells, car horns and music coming from riverside parks. They will slip under hundreds of kayaks, dinghies, motorboats, rowing sculls and paddleboards and dart through the shadows cast by a total of thirteen bridges. At three different points they will muscle their way up fish ladders to get past the dams that punctuate the upper reaches of the river. They will generally ignore baited hooks and garish lures cast by anglers. And they will try to evade the herring gulls, cormorants, herons, striped bass, snapping turtles, and even the occasional bald eagle that love to eat them.

Last year, an estimated 420,000 herring made it through this gauntlet and into the safety of three urban ponds where they could lay their eggs.

And almost no one noticed.

That an urban river should teem with wildlife while serving as a magnet for human recreation no longer seems remarkable to the people of this part of Boston. Few are familiar with the chain of human actions and reactions that produced this happy outcome. Fewer still know that for most of the past 150 years, the Mystic River was seen as an eyesore, a civic disgrace, and a monument to inertia, indifference, and greed.

In this sense, the Mystic is an extreme example of a paradoxical pattern repeated in urban waterways around the world.

First, humans discover the advantages of living next to rivers, which provide a convenient source of drinking water, food, transportation and waste disposal. For a few decades — or even centuries — these uses coexist, even as people downstream begin to complain about the smell. A Bronze Age settlement eventually becomes a trading post, which grows into a medieval town and, centuries later, an industrializing city, smell and waste building up along the way. Until one hot day in the summer of 01858 a statesman in London describes the River Thames as “a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors.”

Civil engineers are summoned, and they deliver the bad news. The only way to resurrect the river and get rid of the smell is to install a massive system for underground sewage collection and pass strict laws prohibiting industrial discharges. The necessary infrastructure is staggeringly expensive and will take years to build, at great inconvenience to city residents. Even after the system is completed, the river will need at least half a century to gradually purge itself to the point where swimming or fishing might once again be safe.

The implication of this temporal caveat — that politicians who announce the project will be long dead when it delivers its full intended benefits — would normally be a non-starter for a municipal budget committee. But the revulsion provoked by raw sewage, and its power as a symbol of backwardness, make it impossible to postpone the matter indefinitely. In London, the tipping point came during the “Great Stink” of 01858, when the combination of a heat wave and low water levels made things so unbearable that Parliament was forced to fund a revolutionary drainage system that is still in use today.

In city after city, similar crises set in motion a process that can be neatly plotted on a graph. Increasing investments in sanitation infrastructure and stricter enforcement of environmental laws gradually lead to better water quality. Fish and waterfowl eventually return, to the amazement of local residents. Riverfront real estate soars in value, prompting the construction of new housing, parks, restaurants and music venues. Generations that had lived “with their backs to the river” rediscover the pleasures of relaxing on its banks. In many European cities, once-squalid waterways are now so immaculate that downtown office workers take lunch-time dips in the summer, no showers required. In Bern, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, some people “swim to work.”

Then, in the final stage of this process, everyone succumbs to collective amnesia.

In Ian McEwan’s 02005 novel Saturday, the protagonist briefly reflects on the infrastructure that makes life in his London townhouse so pleasant: “…an eighteenth-century dream bathed and embraced by modernity, by streetlight from above, and from below fiber-optic cables, and cool fresh water coursing down pipes, and sewage borne away in an instant of forgetting.”

While the engineering, biology and economics of river restorations are relatively straightforward, the stories we tell ourselves about them are not. “An instant of forgetting” could well be the motto of all well-functioning sanitation systems, which conveniently detach us from the reality of the waste we produce. But the chain of events that brings us to this instant often begins with the act of remembering an uncontaminated past.

Call it ecological nostalgia. A search of the words “pollution” and “Mystic River” in the digital archives of the Boston Globe turns up nearly 700 items spread over the past 155 years, and offers a useful proxy for tracking the perceptions of the river over time. We think of pollution as a modern phenomenon, but in the late 19th century the Globe was full of letters, reports and opinions recalling the river in an earlier, uncorrupted state. In 01865, a writer complains that formerly delicious oysters from the Mystic have been “rendered unpalatable” by pollution. In 01876 a correspondent claims that as a boy he enjoyed swimming in the Mystic — before it was turned into an open sewer. Four years later a writer laments that the river herring fishery “was formerly so great that the towns received quite a large revenue from it.” And by 01905, a columnist calls for the “improvement and purification” of the Mystic, urging the Board of Health and the Metropolitan Park Commission to work together on “the restoration of the river to its former attractive and sanitary condition.”

These sepia-colored evocations of a prelapsarian past are a recurring feature of river restoration narratives to this day. “Sadly, only septuagenarians can now recall summer days a half century earlier when the laughter of children swimming in the Mystic River echoed in this vicinity,” writes a Globe columnist in 01993. Last year, in a piece on the spectacular recovery of Boston’s better-known Charles River, Derrick Z. Jackson quoted an activist who believes such images were critical to building public support for the project: “people remembered that their grandmothers swam in the Charles and wanted that for themselves again.” Whether or not anyone was actually swimming in these rivers in the mid-20th century is irrelevant — the idea is evocative and, as a call to action, effective.

But the notion that a watercourse can be healed and returned to an Edenic state is also disingenuous. As Heraclitus elegantly put in the fourth century BC, “No man ever steps into a river twice; for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.” Biologists are quick to point out that the Mystic watershed will never revert to its 17th century state. As chronicled in Richard H. Beinecke’s The Mystic River: A Natural and Human History and Recreation Guide (02013), when English colonists arrived they encountered a thinly populated tidal marshland where the native Massachussett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket tribes had lived sustainably for at least two thousand years. Since then, the Mystic and its tributaries have been dammed, channelized, straightened and dredged into an unstable ecosystem that will require active maintenance in perpetuity.

As the physical river has changed, so have the subjective justifications for restoring it. The Boston Globe archives show that for a 50-year period starting in the 01860s, people were primarily motivated by the loss of oysters and fish stocks described above, and by fears that exposure to sewage might lead to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. But by the time of the Great Depression, the first municipal sewage systems had largely succeeded in channeling wastewater away from residential areas, and concerns about the river had found new targets.

Writers to the Globe began to complain that fuel leaks from barges on the Mystic were spoiling “the only bathing beach” in the city of Somerville, one of the main towns along the river. In 01930, the Globe reported that local and state representatives “stormed the office of the Metropolitan Planning Division yesterday to request action on the 29-year-old project of improving and developing certain tracts along the Mystic riverbank for playground and bathing purposes.” A decade later, not much had changed. “For years,” claimed an editorial in 01940, “the Mystic River has been unfit for bathing because of pollution and hundreds of children in Somerville, Medford and Arlington have been deprived of their most natural and accessible swimming place.”

In the 01960s and 70s, this emphasis on recreational uses of the river broadened into the ecological priorities of the nascent environmental movement. Apocalyptic images of fire burning on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River galvanized public alarm over the state of urban waterways. President Lyndon Johnson authorized billions of dollars in federal funds to “end pollution” and subsidize the construction of new sewage treatment plants. And the Clean Water Act of 01972 imposed ambitious benchmarks and aggressive timelines for curtailing source pollution.

Suddenly, the tiny community of Bostonians who cared about the Mystic felt like they were part of a global movement. Articles from this period feature junior high schoolers taking water samples in the Mystic and collecting signatures for anti-pollution petitions they would send to state representatives. The petitions worked. News of companies being fined for unlawful discharges became routine, and the Globe began inviting readers to report scofflaws for its “Polluter of the Week” column. An article in 01970 described a group of students at Tufts University who spent a semester conducting an in-depth study of the river and recommended forming a Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) to coordinate clean-up efforts.

The creation of the MyRWA, which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary, mirrors the rise of activist organizations that would become powerful agents of accountability and continuity in settings where municipal officials often serve just two-year terms. In a letter to the editor from 01985, MyRWA’s first president, Herbert Meyer, chastised the regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for ignoring scientific evidence regarding efforts to clean Boston Harbor. “Volunteer groups like ours have limited budgets and no staff,” he wrote. “Our strengths are our longevity – we remember earlier studies – and objectivity. We speak our minds: Not being hired, we cannot be fired, if we take an unpopular stand.”

MyRWA volunteers began collecting regular water samples and sending them to municipal authorities to keep up pressure for change. They also found creative ways to get local residents to overcome their preconceptions and reconnect with the river: paddling excursions, a series of riverside murals painted by local high school students, periodic meet-ups to remove invasive plants and a herring counting project that tracks the fish on their yearly spawning run.

For the last two decades, coverage in the Boston Globe has celebrated the efforts of these and other volunteers (as in a 02002 profile of Roger Frymire, who paddles up and down the Mystic sniffing for suspicious outfalls: “He has a really sensitive nose, particularly for sewage”). But it has also continued to display the negativity bias that is perhaps inevitable in a daily newspaper. In a 02015 editorial, the paper urges city officials to “Set 2024 goal for a swimmable Mystic” as part of an (ultimately abandoned) bid to host the Olympic Games. “If Olympic organizers moved the swim… to the Mystic River, the 2024 deadline could spur the long-overdue clean-up of Boston’s forgotten river,” the editorial claimed, as if the Boston Globe had not chronicled each stage of that clean-up for more than a century.

For Patrick Herron, MyRWA’s current president, this “generational ignorance” is to be expected. “If we could all see what our great-great-grandparents saw, and then we zoomed to the present, we would be appalled,” he said in a recent interview. “But we can only remember what we saw 20 or 30 years ago, and things today aren’t that much different.”

Baselines shift: each generation takes progress for granted and zeroes in on a new irritant. Herron said that MyRWA’s current crop of volunteers, like their predecessors, brings a new vocabulary and fresh motivations to the table. The initial focus on water quality has morphed into a struggle for “environmental justice,” which explicitly elevates the needs of ethnic minorities, lower-income residents, and other marginalized groups that have been disproportionately affected by the Mystic’s problems. Climate change, and the increasingly frequent flooding that still causes raw sewage to spill into the river, is now at the center of debates about the next generation of infrastructure investments needed to protect the Mystic.

Lisa Brukilacchio, one of the early members of MyRWA, thinks these shifts are inevitable. “Change is cyclical,” she said. In her experience, young volunteers show little interest in what their predecessors achieved. “You fix one thing and it’s, like, over here there’s another problem. People have short attention spans, and they want to see something happen now.”

John Reinhardt, a Bostonian who was involved in MyRWA’s leadership for over 30 years, agrees with Brukilacchio and adds that this indifference to the past may be essential to preventing complacency. “I think that there is incredible value to the amnesia,” he said. “Because of the amnesia, people come in and say, damn it, this isn’t right. I have to do something about it, because nobody else is!”

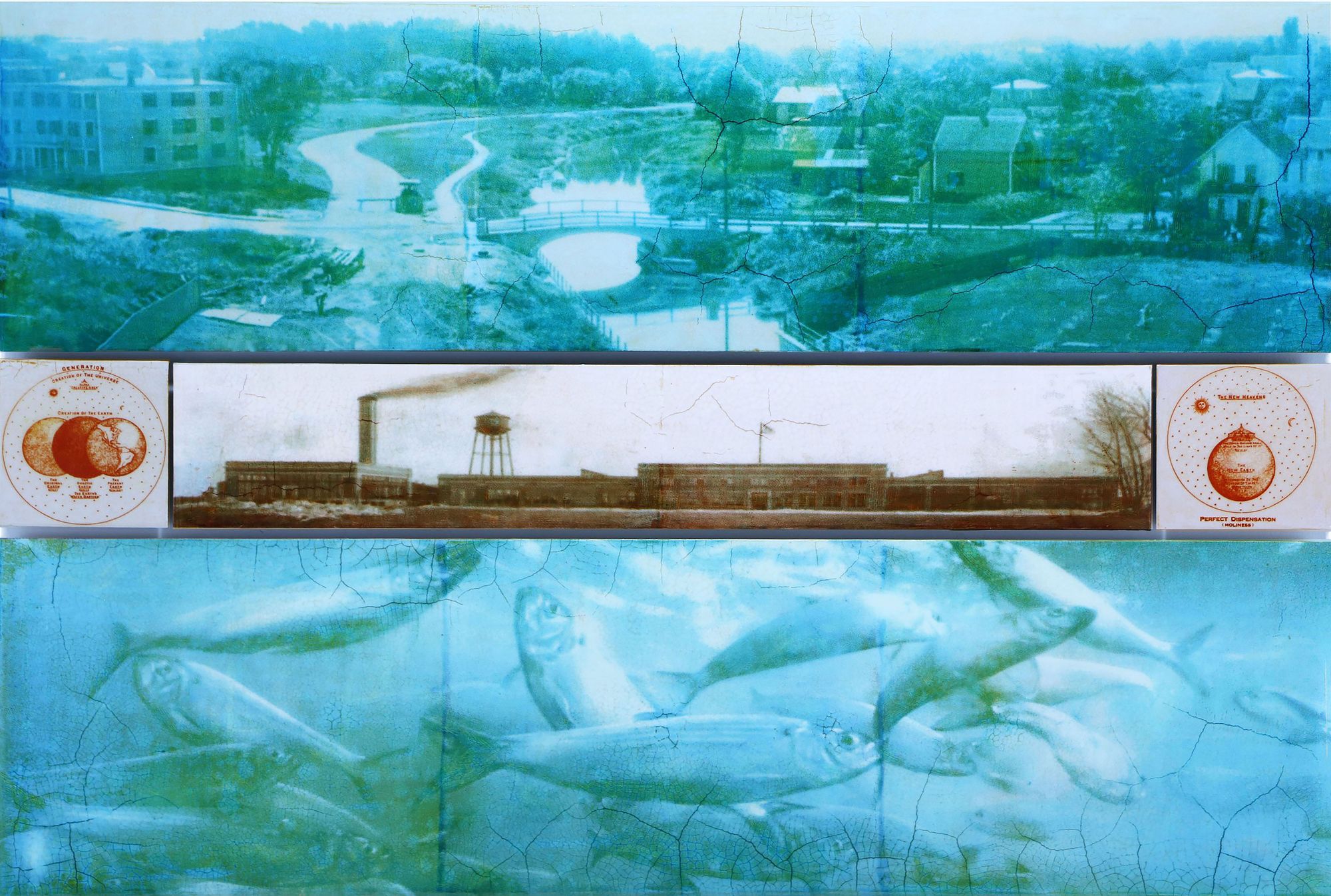

To generate a sense of urgency and compel action, it may perhaps be necessary to minimize both the scale of previous crises and the contributions of our forebears. Bradford Johnson, an artist based in Somerville, sees the Mystic as a canvas onto which each generation overlays its own fears and aspirations. In a series of paintings (three of which accompany this essay) Johnson juxtaposes archival images of the Mystic, fragments of magazine advertising, photos of local wildlife, and single-celled organisms viewed under a microscope. In each panel, layers of paint are interspersed with multiple coats of clear acrylic, creating a thick, semi-translucent surface that cracks as it dries.

Johnson’s paintings dwell on the arbitrary ways in which we select and manipulate memories of a landscape. They also incorporate details from elaborate charts created by Clarence Larkin (01850–01924), an American Baptist pastor and author whose writings were popular among conservative Protestants. The charts were studied by believers who wanted to understand Biblical prophecy and map God's action in history. I interpret Johnson’s inclusion of these panels as a nod to the role of human will in the destruction and subsequent reclamation of a landscape, and to religious and secular notions of redemption.

It so happens that the timescales required to resurrect an urban river are similar to those needed to construct a gothic cathedral. Both enterprises depend on thousands of anonymous individuals to perform mundane, often-unglamorous tasks over several generations.

But the similarities end there. Cathedrals emerge from a single blueprint in predictable and well-ordered stages. When completed, they preserve the work of each mason, carpenter and stained-glass artisan as a static monument to a shared creed. They are made of stone to underscore the illusion of permanence.

Rivers, with their ceaseless, shape-shifting flux, remind us that none of our labor will last. The process of reclaiming a dead river is the opposite of orderly: it lurches through seasons of outrage and indifference, earnest clean-ups followed by another fuel spill, budget battles and political grand-standing, nostalgia and frustration. It is messy, elusive, and never actually finished.

Yet in Boston and many other cities, this process is working. And as testaments to a different kind of human agency, resurrected rivers are, in their own way, no less majestic than the structures at Canterbury or Notre-Dame.

“Cathedral thinking” has long been a slogan among evangelists for multi-generational collaboration. “River restoration thinking” may be a more apposite model for tackling the problems of our fractious age.

The hunt begins at birth; the mission becomes clearer and clearer. But no man can act alone. By cross-referencing Google Flights, Kayak, Expedia, Hopper, and Delta’s Twitter bot, you should be able to secure and execute your destiny: a $650 ticket from Denver to Minneapolis via Kansas City.

I went down a river once when I was a kid. There’s a place in the river—I can’t remember—that must have been a gardenia plantation or flower plantation at one time. It’s all wild and overgrown now, but for about five miles, you’d think heaven just fell on the earth in the form of gardenias. For the voyage, I packed one native pelt, a pound of water buffalo jerky, and my machete. That should suffice for your six days at Disneyland Paris.

I watched a snail crawl along the edge of a straight razor. That’s my dream; that’s my nightmare. Crawling, slithering, along the edge of a straight razor… and surviving. My other nightmare was when my Uber took a wrong turn on my way to LAX, and I missed my flight to Hanoi by ten minutes.

It’s impossible for words to describe what is necessary to those who do not know what horror means. But I’ll give it a shot: the TSA line.

A man came to this village once. He bore credentials I had yet to see before. Or since. A CLEAR representative, he called himself. I let him in. He investigated my eyes, my thumbs. He told me he was scanning them. Upon arrival at Chicago Midway, I was met with a grim fate. It wouldn’t read them. It wouldn’t read them.

You’re an errand boy sent by grocery clerks to collect a bill. I see; I am mistaken. You are a steward of this Chili’s Too. In that case, I will have an order of Southwestern eggrolls and a Tiki Beach Party margarita.

Have you ever considered any real freedoms? Freedoms in the opinion of others. Even in the opinions of yourself? Because they’re all out the window at this overcrowded American Airlines Admirals Club.

Are my methods unsound? Oh, I apologize to my fellow travelers in row 26. My Bluetooth headphones haven’t connected to my phone, so it’s been blaring “The Soft Parade” into your eyeballs.

If I were to be killed, I would want someone to go to my home and tell my son everything. Everything I did, everything you saw. Because there is nothing I detest more than the stench of lies. To do that, you’ll have to make it to Georgia and its Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson Airport. On second thought, I detest Hartsfield more. So to recap: Atlanta’s airport, one. Lies, two. In the detestation rankings.

We train young men to drop fire on people, but their commanders won’t allow them to write “fuck” on their airplanes because it’s obscene! I’ll tell you what’s obscene: those furry animals on the side of the Frontier crafts.

As long as cold beer, hot food, rock ’n’ roll, and all the other amenities remain the expected norm, our conduct of the war will only gain impotence. Also, the United flight attendant said they were out of everything besides the Tapas Snackbox.

Arguing with Supreme Court opinions, as one does — in this case Counterman v. Colorado. Now, let me be quick to say that the comment I am making above is really irrelevant to the case, because almost nothing in the opinion or the dissent is about what Counterman did or didn’t do — it’s almost exclusively an in-house debate about what criteria should be used to determine whether given speech-acts are or are nor protected by the First Amendment right to freedom of speech. Basically, the judgment of the Court could be summarized thus: “Hey Colorado, you went after Counterman by claiming that he was making ‘true threats’ and further arguing that one should use a reasonable-person standard to decide what makes something a true threat, but you went about it all wrong. The guy may well be guilty of something, but the particular argument you made against him is inconsistent with First Amendment protections, so we’re going to vacate your decision and send it back to you. Please do better in the future.” So now Colorado has to decide whether to try Counterman again using a different set of standards.

I think this decision will be really consequential in the long term. For now just a handful of thoughts:

The bottom line is this: Counterman communicated true threats, which, everyone agrees, lie outside the bounds of the First Amendment’s protection.” Ante, at 4. He knew what the words meant. Those threats caused the victim to fear for her life, and they “upended her daily existence.” Ante, at 2. Nonetheless, the Court concludes that Counterman can prevail on a First Amendment defense. Nothing in the Constitution compels that result. I respectfully dissent.

Paisley Rekdal’s work is urban, the poetry an explosion of language, the ranging cast of mind in the spirit of Albert Goldbarth or Linda Gregerson. Like these poets her lines are made of long hypotactic sentences, linking image and language on a string of wondrous beads, leaping in and through those long lines like C. K. Williams. Rekdal infuses them with a vibrant grace, a cultured smoothness, a voracious reading. She grew up in Seattle, studied medieval literature in the prestigious University of Toronto program, abandoned those studies to give herself over to writing poetry, carrying through all of it, meanwhile, an abiding interest in nonfiction, and an interest in writing about things you weren’t supposed to write about, like bad sex. She carried also an interest, always, in unclassifiable media. So there’s a fundamental genre-restlessness to Rekdal’s passions, but she doesn’t equate esoteric with experiment. Her memoir, Intimate, is part ekphrasis, part lyric essay, part poetry sequence, part collage as it tells the story of her parents’ mixed-race marriage—her father’s lineage is Norwegian, her mother’s Chinese—by way of Edward Curtis photographs and the story of his Native American guide Alexander Upshaw. She’s written a book on cultural appropriation—the most thoughtful, complicated, lyrical account I’ve read—and even in her collections, such as Six Girls without Pants—she can shift, page by page, poem by poem, from the disjunctive to the Horatian, mixing modes like a chef.

This is partly what makes her latest book, which began life as a hypertext—a website, an experience of poetry, image, video—not only a natural emergence from her oeuvre, but also a daring and serious attempt to move from a work of online art to a book, pushing at the inherited limitations of both. West: A Translation takes its starting point from one of the poems carved into the wooden barracks at Angel Island, the place where immigrants, particularly Chinese immigrants, endured the horror of being stateless, wondering if they’d be allowed entry into new life. Some killed themselves. Some tore poems into the walls that held them. Rekdal has taken one of these, a little elegy for a suicide, and translates each character of it by way of a new poem—or image. It’s as if she’s taken each character and perspective and turned it into a separate study of the railroad, and the collection of these railroads, radiant expansions of their original source, is the book. In the process, Rekdal gives an account of the history of the western part of the United States as a history of the transcontinental railroad—built by poor Chinese immigrants, mostly from Guangdong Province. The book, which began life as a website, was commissioned by the Spike 150 Foundation to “commemorate” the 150th anniversary of the installment of the final spike of the railroad. That happened in Salt Lake City, a city—and in a state—that Rekdal has, a little bit to her own surprise, become rooted in, made home. Rekdal’s life, with its blend of commitments and inheritances and meanderings, seems in many ways to embody well the life of a twenty-first-century western American. Which makes her voice the perfect voice for a moment in which we’re grappling more directly than ever with the fallout, the damage and trauma, left in the wake of that railroad’s completion. The true costs of “westward expansion.” And though the transcontinental railroad’s last spike was driven in in Utah, it’s true end was what it pointed toward, and what its opening up opened up: California. Where an anonymous Chinese migrant wrote this poem on the wall at Angel Island, rendered in Rekdal’s English, and from which she makes her book:

Sorrowful news indeed has passed to me.

On what day will your wrapped body return?

Unable to close your eyes, to whom can you tell your story?

Had you known, you never would have made this journey.

Eternity contains the sorrow of a thousand bitter regrets.

Missing home, you face in vain Home-Facing Terrace,

Your ambitions, unfulfilled, buried under earth.

Yet I know death can’t turn your great heart to ashes.

JESSE NATHAN: You did graduate work in medieval studies. Would you say you have a medieval sensibility in some way? What does that mean, and how does it manifest in your poems? (What does it mean in terms of your genre-blending books like Intimate or West?) What kind of lines or tones or forms does it lead you to in your poetry?

PAISLEY REKDAL: I have been thinking about your question for several weeks now, because I feel that the “medieval” strain in my work is a sensibility I share with and can immediately intuit in other modern and contemporary writers, but haven’t articulated for myself. I think there are two ways that my medieval studies training has influenced me. The first way is that I’m drawn to interdisciplinary work, whether it’s multimodal or digital writing projects or whether it’s writing that crosses different disciplinary lines, which medieval studies as a field forces its scholars to do. There are—relatively speaking—few surviving intact texts from the medieval world, and there was also a very limited literate audience that could have gotten hold of them, so you have to be creative in how you approach both cultural and textual interpretation. You don’t just read the primary sources, you also turn to art that was produced at the same period of time, and theological arguments circulating at the moment, you consider the political climate in question, and maybe also look into whatever martial or public health crises were brewing.

Taking one question and looking at it from myriad positions allows for a kaleidoscopic or fractal understanding of a literary text and how art itself gets created. It’s certainly helped me in works like The Broken Country, where I think not just about a single violent crime committed by a Vietnamese refugee that took place at a grocery store near my house, but how this crime might speak to larger questions of Southeast Asian immigration and assimilation into the American West, the legacy of war, medical and sociological understandings of trauma, the metaphors we use to depict violence, etc. With West, my medieval training probably influenced my desire to research all the different ways the train altered American cultural life. Obviously, that’s an impossible task to accomplish, but one thing really stuck out to me about the railroad’s history as I studied it: how little we know about the daily life, thoughts, and feelings of the workers. We tend to collect the cultural products of the owners of capital, not its producers—especially if the producers of capital aren’t functionally literate in the owners’ language. When you study medieval literature and culture, of course, you are also looking into an absence: you know what the aristocracy believed, and you know what the literate wanted. But those that don’t fit into these categories? That’s an entire world that’s effectively been rendered silent, and I think that question of silence has always haunted me as a writer.

(Side note: This is perhaps the only thing that saddens me about the possible demise of Twitter, because the wealth of information produced by “average” humans about what they eat, read, watch, think, feel, like, and hate about their moment of time is a medievalist’s wet dream.)

But the second way that my medievalist background has influenced me is more intangible. The “medieval sensibility,” as you call it, really speaks to what I was drawn to in medieval literature as a whole, which is its sense of—for lack of a better term—genre-lessness or maybe genre-explosiveness. You would clearly call most medieval poems “poetry,” of course, but what drew me to work like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was the sense of English itself—the language and its prosody—staggering to its feet, trying to figure out its own poetic rhythms as a newly evolving language.

I also love the way that so many medieval texts call back to classical ones, but then alter/pervert/estrange them from their original sources, like you see with Marie de France’s take on Ovid in Le Laustic, or the fact that Gawain actually opens with a call back to the fall of Troy and then becomes a fundamentally foundational narrative about England. There’s a wildness to Middle English poetry that comes—I believe—from the fact that it’s in a liminal place—neither strictly French nor wholly Anglo Saxon, not part of the classical world even as Rome has its political and cultural tentacles throughout Europe. These are poems that are invested in vision—actual religious vision!—as much as myth and art and history, and all of this combines in the most heady ways. These are poems that feel as if they are inventing their own forms, even as they are reinventing inherited subject matters.

It’s funny to think about writing with and against “risk” now, because I think workshops and the publishing industry and social media have all created such powerful, if occasionally obscure, “norms” for what literature is and looks like. When I read something like “The Land of Cokaygne,” I’m actually filled with jealousy. It’s not that these writers didn’t understand limitation or “rules” (that’s actually the point of the humor in “The Land of Cokaygne”), but that there seemed to be a more porous boundary between types of experience and knowledge, thus types of writing and perception. That’s what I aspire to be as a writer: someone who pushes through and beyond accepted genres or forms. I want my conscious to be more permeable. I want to be always at the beginning of things, without knowing what my writing—or my own self in the world—is supposed to become.

1. Bleb

2. Etnies

3. Furuncle

4. Stussy

5. Mormal

6. Kith

7. Lues

8. Vetements

9. Milk Leg

10. Cav Empt

11. Icterus

12. Huf

13. Dropsy

14. Temu

15. Aphthae

16. Tropicfeel

Streetwear Brand: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16

Skin Condition: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15

Stop all the clocks, cut off the…

What?

Yes, stop all the clocks.

Yes, all the clocks.

Sorry?

I do realise there are lots of clocks.

Just stop them.

What do you mean “how”?

Are you honestly telling me

You don’t know how to stop a clock?

Just take the batteries out!

Fine, if it plugs in, take the plug out.

I am aware it will start flashing 00:00

Yes, that counts as stopped.

Yes, even when it’s flashing.

I know it’s annoying, this whole thing is annoying.

Why are you making this so difficult?

Wind-up clocks? Erm…

Well, just stick your finger in there.

Or something.

Look.

Please calm down.

Stop shouting.

Yes, I want you to stick your finger in,

All the wind-up clocks in the world.

Yes, even Big Ben.

Yes, even the Rathaus-Glockenspiel.

I have thought this through!

I have!

I’m not making up the rules as I go along.

Fine, then just throw a cloth over them.

Please stop crying.

Please.

I know you’ll hear them ticking.

No, “hide all the clocks” wouldn’t work better.

Because it wouldn’t.

Okay, okay.

This isn’t really about clocks is it?

This is about the cowboy hat.

I was being supportive;

I wasn’t giggling.

You always do this.

All I want to do is stop all the clocks,

Then suddenly it’s all about you.

And your hats.

I’m sorry.

I’m sorry, please stop making that noise.

How about this?

Stop some of the clocks.

Hide any that are remaining.

Does that work better for you?

Fine, let’s do that then.

We’ll pick out some hiding cloths later.

Goodness, we better get a move on,

Or we’ll be late for the funeral,

What time is it now?

Oh. Right.