Amanda Holmes reads Nizar Qabbani’s poem “When I Love You,” translated by Lena Jayyusi and Jack Collum. Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “When I Love You” by Nizar Qabbani appeared first on The American Scholar.

As Rhode Island School of Design’s (RISD) 18th president, Crystal Williams believes that education, art and design, and staying committed to equity and justice are essential to transforming our society. At RISD, the Detroit-born activist is working to drive meaningful change centered on expanding inclusion, equity, and access. To back that up, Crystal has more than two decades of higher education experience as a professor of English as well as serving in roles that oversaw diversity, equity, and inclusion at Boston University, Bates College, and Reed College. The ultimate goal behind Crystal’s role at RISD is to enhance the learning environment by making sure it includes diverse experiences, viewpoints, and talents.

However, Crystal’s talents go beyond the halls and classrooms of colleges and universities – she’s also an award-winning poet and essayist. So far, she’s published four collections of poems and is the recipient of several artistic fellowships, grants, and honors. Most recently Detroit as Barn, was named as a finalist for the National Poetry Series, Cleveland State Open Book Prize, and the Maine Book Award. Crystal’s third collection, Troubled Tongues, was awarded the 2009 Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Prize and was a finalist for the 2009 Oregon Book Award, the Idaho Poetry Prize, and the Crab Orchard Poetry Prize. Her first two books were Kin and Lunatic, published in 2000 and 2002. Crystal’s work regularly appears in leading journals and magazines nationwide.

Today, Crystal Williams is joining us for Friday Five!

Originally, I was going to write about a place that inspires me. But when I truly started to consider places I find inspiring, I realized that each of them elicits and enables silence and stillness, a refraction of silence (at least for me). So then, silence itself is the thing that inspires me. Silence inspires me to delve and investigate and allows me to situate myself in wonder and awe – in the amplitude and magnitude of who and what and how we are as a species, to sometimes take issue with personal fears or traumas or worse – the behaviors that ultimately impede personal and spiritual growth or insight.

For me, silence is a great gift. Perhaps the greatest. It is a balm. Through it, I connect to the world not as Crystal Williams of this particular body but as a congregation of embodied energy and spirit. In this way, it is the catalyst through which all good art, poetry, ideas, and leadership emerge. So it is among the most inspirational things in my life – and among the most rare, given my life.

I admire many poems. But Lucille Clifton’s “won’t you celebrate with me” (which is how it is commonly known although Clifton did not, in “Book of Light” originally title the poem), is the one that inspires me the most. It is a poem that speaks to resilience, fortitude, bravery, imagination, hope, and it names what being a Black woman in the United States can and often does elicit.

“won’t you celebrate with me

what I have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

….

…come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.”

Nancy Wilson, Carnegie Hall, 1987 \\\ Video still courtesy YouTube

There are moments in art when an artist transforms one thing into another, utterly broadening, deepening, and transmuting the original meaning. In this live version of “How Glad I Am,” her encore performance at the 1987 “Live at Carnegie Hall” performance, Wilson – a vocalist I listened to obsessively as a younger person – transforms a simple song between lovers into a rousing tribute from an artist to her audience. This performance is the most profoundly loving example I have witnessed of an artist speaking directly and forcefully to the mutuality between artists and audiences. And it’s become a kind of personal soundtrack when I’m walking through my life, especially my life as a poet and now as president. Often, when I’m among creatives, I hear Wilson’s gorgeous, gravely voice imploring: “you don’t know how glad I am [for you].”

Listen, these young people at RISD and young creatives everywhere are our best-case scenario. They are our visionaries, if only we can amplify them, listen to them, and then get out of their way. They have all the love (and strategy and insight and knowledge) we need if we can help them wield it successfully. They have all the intelligence and ingenuity we need to help solve our challenges and advance what is good, right, and just among our species. Added to those attributes are other facts: they are funny and curious and eager to learn and gloriously unusual.

I watch them here at RISD in their multi-colored outfits, hair-dos, and platform shoes, giggling with each other in front of the snack machine or intensely applying their best thinking to each others’ work during critiques. I listen to them grappling with big ideas, considering, reconsidering, and redesigning our world as if on slant, eschewing the boxes into which we have crammed stale ideas that continue to guide our actions. And I watch them in their magnitude – in the more quotidian actions of their lives trudging up and down the severe hill outside with their humongous portfolios and unwieldy art projects, and think through it all, “Wow” and think “to be so young and so powerful and necessary” and think “thank God” and think “Thank you, young people, for saying yes to the impulse that brought you here.” Not only do they inspire me, they humble me and they – each one of them – feel like a balm, like hope incarnate.

My folks married in 1967 against all odds. They were of different ethnicities – he Black, she white. Different places – he from the Jim Crow South, she from Detroit, Michigan. Different eras – he born in 1907, she in 1936. Different careers – he a jazz musician and automotive foundry worker, she a public school teacher. And different educational backgrounds – he, we think, not a high school graduate, she a college graduate. And yet, they found each other over the keys of a piano and decided, against society’s cruel eye and hard palm, to love each other and to love me. I now understand the courage it took for all of that to be true, for them to make a way, for them to walk through the world in 1967 as a couple and with me as their child. That courage inspires me. Those decisions inspire me. They inspire me. Everyday. All day.

Kin by Crystal Williams, 2000 \\\ Williams utilizes memory and music as she lyrically weaves her way through American culture, pointing to the ways in which alienation, loss, and sensed “otherness” are corollaries of recent phenomena.

Lunatic: Poems by Crystal Williams, 2002 \\\ Williams confronts large-scale social and cultural events such as September 11, the death of Amadou Diallo, and the Chicago Race Riots in addition to exploring the often paralyzing terrain of loss, desire, and displacement. Among its most common themes is personal responsibility.

Troubled Tongues by Crystal Williams, 2009 \\\ In each of the three sections of this book is a prose poem meant to be read aloud in which a character, interacting with other characters, is named for a quality. They are Beauty, Happiness, and Patience.

Detroit as Barn: Poems by Crystal Williams, 2014

This post contains affiliate links, so if you make a purchase from an affiliate link, we earn a commission. Thanks for supporting Design Milk!

Amanda Holmes reads Adam Zagajewski’s poem “En Route,” translated by Clare Cavanagh. Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “En Route” by Adam Zagajewski appeared first on The American Scholar.

Leopoldine Core’s aura photo, courtesy of the author.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Leopoldine Core’s “Ex-Stewardess” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 244.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

Often a poem begins wordlessly. It’s as if the text is a reply to some cryptic spot in the back of my brain that I have become attracted to. I’m alerted to the presence of something that isn’t solid. It has more to do with feeling, tempo, scale, and temperature. I’m so focused on that emanating region that, even though I’m using words, my experience—the start of it—is wordless and meditative.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? (Are there hard and easy poems?)

Some poems come quick and others take a while. But maybe the one that took years was easier in the end—I don’t know. Certain poems require many rounds of rewording. When this happens I will rewrite one line forty or more times, then narrow it down to thirty, then fifteen, then five, then choose.

But this poem was realized fairly quickly and required zero rewording. That happens sometimes. I tried rewording certain parts at different points but always wound up reverting to the original. The editing I did consisted of deleting maybe seventy percent of what was there, changing the order, capitalizing certain letters, and adding line breaks. I might have added a comma but I don’t think so.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

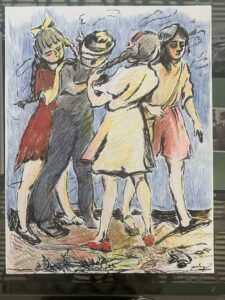

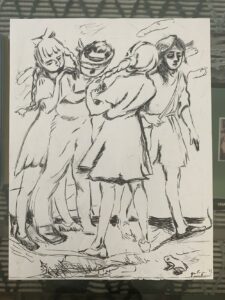

Occasionally my friend Jane Corrigan will send me pictures of her paintings and drawings. There are two she showed me around that time—one is a pen drawing and the other is a Xerox of that same drawing that she drew over with pen and colored in with pencil. Jane’s images are infused with such narrative possibility—I like to stare at them for a long time, putting order to the plot. This one seems like a scene from some lost Jane Bowles story.

I wasn’t thinking consciously of these drawings while writing the poem, but there’s something so joyful and stimulating about discourse with friends. I like talking about art that isn’t mine.

Courtesy the author and Jane Corrigan.

Courtesy the author and Jane Corrigan.

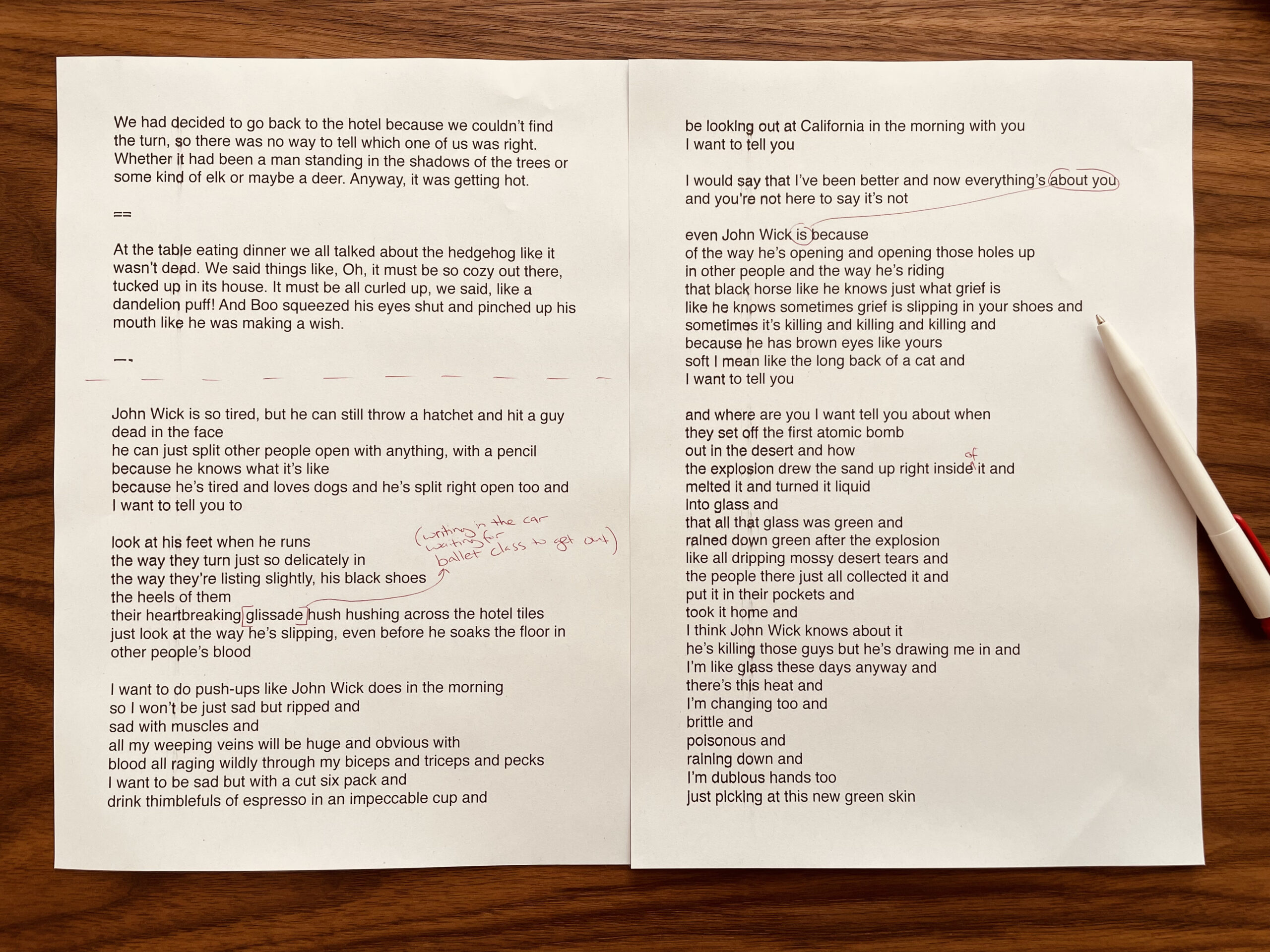

What else were you listening to / reading / watching while you were writing this poem?

I was reading a collection of interviews with the filmmaker Claude Chabrol. I underlined this sentence—“I like mirrors, because they are a way of crossing through appearances.” He was talking about manipulating space but I was drawn to a conceptual meaning of the statement—how something solid that reflects the surface of things can also function as an entryway, a portal.

I was listening to Tangerine Dream, Ryuichi Sakamoto, “Dance II” by Discovery Zone, and this mournful song “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” performed by Mia Farrow in The Muppets Valentine Show in 1974. I love how sincerely she sings to that puppet. She sounds a little like Nico. And there’s something about the confluence of optimism and despair in her voice that might have influenced me.

It also seems relevant to mention that I had gotten an aura photo taken around that time—I kept looking at it. The aura photo I had taken a few years before was mostly red with a cloud of yellow and orange. I was told at the time that the color red implies a closeness to Earth.

But this one was so blue. I kept wondering what that meant. Where was my spirit in relation to Earth? Was it farther from Earth now? I was—am still—grieving the loss of someone I love dearly, and looking at the photo made me think of a sky within.

What was the challenge of this particular poem?

Writing in code. And leaving room for interpretation. The metaphors are there—the stewardess, travel, the dog, the sky, et cetera—but they can also be taken literally. They are what they are and they are something else too.

The poem could be about someone who really reincarnated all these different times and remembers those past lives—though I was thinking more about how we reincarnate many times within a single lifetime, both in terms of how we are seen and in terms of how we really are. We are reborn in the sense that we transform. And yet we carry impressions of the interminable past within us.

I was also thinking about the experience of being objectified over and over. And how those experiences can shape one’s worldview, their sense of what is possible and impossible—and also their sense of time. Stewardess is a dated term that seems, in the poem, to be asking, But has anything changed? Can one really be an ex-stewardess if the treatment is the same? Then it becomes a question of hope—what it might be made of. The poem ends with the act of drawing “an imaginary / animal,” by which I mean the self, and “a field and the / sky”—by which I mean the world. It felt important to depict selfhood in the throes of the imagination—one who works to escape an external gaze, knowing they are not limited to how they are seen, knowing they are multiple.

Leopoldine Core is the author of the poetry collection Veronica Bench and the story collection When Watched, which won a Whiting Award and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. She is a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. Her fiction and poetry have appeared in The Paris Review, PEN America, Apology Magazine, The American Poetry Review, BOMB, and The Best American Short Stories, among others. She has taught at NYU and Columbia University.

Amanda Holmes reads Maxine Kumin’s poem “Morning Swim.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Morning Swim” by Maxine Kumin appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Stanley Kunitz’s poem “The Portrait.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “The Portrait” by Stanley Kunitz appeared first on The American Scholar.

I’m turning 40 in a few months and trying not to think too much of it, but I am getting my bearings a bit.

Yesterday Elisa Gabbert tweeted, “I think I liked magazines more as a kid because the writing was by people older and wiser than me, with different generational interests. Now it’s just, like, writing by my friends, or people who could be? I’m supposed to pay for this? Lol”

I had a good laugh at this. It made me think that a good move at this age might be to start reading the NYTimes for Kids (which I already do) or Teen Vogue or AARP.

This would be the publication equivalent to Kevin Kelly’s advice, “When you are young, have friends who are older; when you are old, have friends who are younger.”

I do feel kind of lucky right now, to be in the middle: I have my kids and their friends for youth spies and for an elder perspective, I ride bikes twice a week with a 75-year-old who is still mad that Dylan went electric.

Everything changes, always, but I’m enjoying this age at the moment.

Thought of this one after witnessing a grown man have a tantrum in public. There but for the grace…

Amanda Holmes reads Rabindranath Tagore’s poem “The Flower-School.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “The Flower-School” by Rabindranath Tagore appeared first on The American Scholar.

To the Formless God

By mid-morning the grey fog burns off Biscayne Bay.

Land surfaces, a silver glint under the veil.

I trust it’s there—I’ve seen its bottlenose before.

For years I’ve prostrated before marble, black stone, brass, burning incense, repeating

God’s name.

There is no one to ask me anything.

Rain floods the highway under construction.

The Bible says, Add enough clay and it becomes slip: sediment and water at once.

No matter how much I read, I am a city of charred rubble folding my

streets-turned-canals in prayer.

On the highway I cross the bridge.

Mist vapors up from the water like the Holy Ghost, like resurrection.

When the city burns away does sea ferry rock back to its prior self?

What becomes of the idol where there is no one to ask anything of—clay doesn’t know

itself as clay.

I’ve never been more flooded yet parched with hymns.

I strain my eyes searching the streets for dolphins.

The Garden Walls Fail

It’s summer and I don’t believe myself nor

my meds of gila monster saliva transfigured

into a chemical that lowers A1C, my summer

body buried so far in the past, it was never a body.

My overall plasticity of joint, of grey matter

long since began its decay. I once prized

your squash, salting slices, squeezing water,

breaking the web of cheese cloth. I can’t recall

what I made of all that yellow. Or your face

in marvel. We too, one summer past the summer

before, no miracle serpent to spit antidote. For now

I’m lost in the strawberries, my hands in cow shit.

The house of us stands. Renovations can wait

until next year. Yes. Next year will be better.

***

Author photo by Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada

Photograph courtesy of Kyra Wilder.

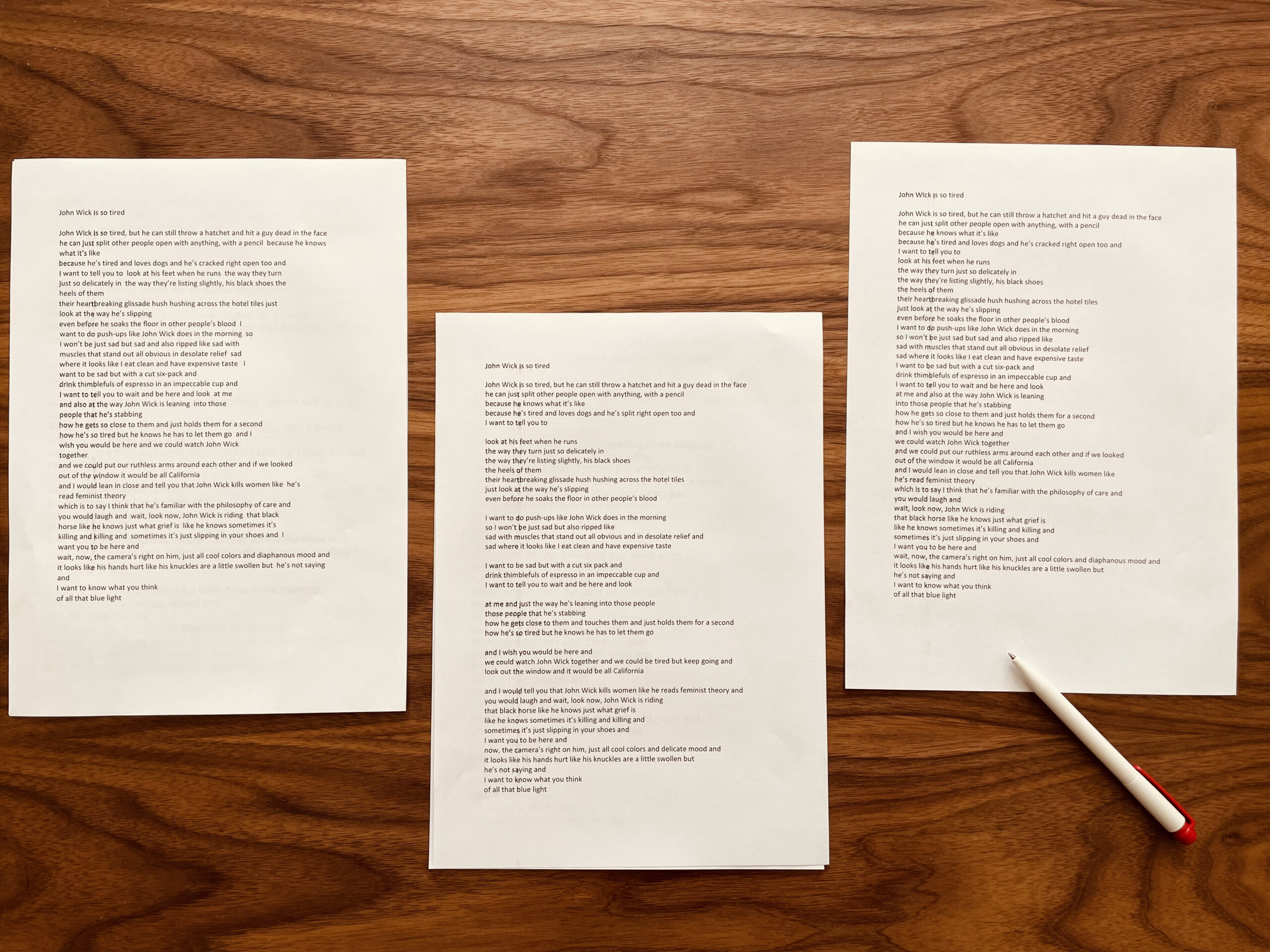

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Kyra Wilder’s “John Wick Is So Tired” appears in our new Spring issue, no. 243.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase?

With the first line. It was something I’d thought a lot about—I run marathons, and in those tense few days before the race, when I’m drinking water and carb loading and meditating on what’s going to happen, I watch John Wick, specifically because of the way Keanu Reeves runs. He looks so tired, but he’s winning.

In the fall of 2021, I was tapering for a marathon and then I had to go to a funeral, and suddenly my John Wick time got invaded by real grief. And John Wick was good for that, too.

What were you reading while you were writing the poem?

I was reading a lot of Ian Fleming that fall. I got pretty obsessed with the fact that he included a recipe for scrambled eggs in a James Bond story. In that story, Bond is completing some kind of mission in New York but also being really whiny about the poor quality of American eggs—to the point that he’s wandering around the city going into bodegas and criticizing them. So, it was either going to be “John Wick Is So Tired” or “James Bond Could Make You Some Pretty Good Eggs.”

Where did you write this poem?

That glissade is in there because I was writing in the car, waiting to pick up my daughter from ballet class. I write all over—sometimes even at my actual desk. I have a print from Bas Jan Ader’s I’m too sad to tell you on the wall. There’s nothing better to stare at when things are going badly.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or to friends or confidantes? If so, what did they say about them?

I showed it to my husband. He’s a math guy and doesn’t read poetry, but he’s usually right about my writing. When he read the first draft, he liked the first half but said he “didn’t get” the ending. Reading that draft again now, I see what he meant.

That version was maybe more like a novel or a short story. We’ve started with John Wick, but by the end we’re lost in the desert. It’s chatty, reaching for all the conversations that are being missed—the speaker wants to watch John Wick and tell the lost person historical asides about nuclear bomb testing sites. Of course they do, but that’s for a novel. In the context of a poem, it’s too much, too close together. I’m hitting the meaning-gong too many times. John Wick (the character, the movies, the Keanu) is so good, and the poem is about this one feeling of where-are-you-right-now-how-could-you-miss-this-one-particular-thing, so we need to stay with John Wick and forget the desert.

After I found an ending that felt more specific and focused and safely clear of novel/short story/essay territory, I sent a copy to my agent, Jon Curzon. He told me he’d once made an Instagram account called Keanu Leaves, which was just full of pictures of Keanu Reeves waving goodbye.

How else did the poem change over time?

I wrote it without stanzas at first, and then decided to break up the poem following the speaker’s thoughts—where the thinking shifted, or where I thought they might pause or take a breath. The stanzas got me closer to the person speaking—they helped me hear how the speaker would say the lines.

As useful as they were, though, the stanzas made the poem too dramatic. They looked like they were trying too hard. We’re starting with a hatchet thrown at someone’s face—we don’t need the additional histrionics of white space. Then it was all playing with line breaks. One of the drafts has two lines with single words. It’s not that I was thinking I might eventually end up with one-word lines—it was that I was breaking the lines up everywhere and leaving them for a while to see how they looked. I was just pushing things around, moving lines back and forth and reading it again every few days. I would open the document, break up lines, and leave it for a bit.

Once I got the poem to the point where, when I looked at it fresh, there wasn’t anything I wanted to change, I sent it off and left it for dead.

Amanda Holmes reads Wallace Stevens’s poem “Sunday Morning.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Sunday Morning” by Wallace Stevens appeared first on The American Scholar.

Amanda Holmes reads Grace Cavalieri’s poem “Three O’Clock 1942.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Three O’Clock 1942” by Grace Cavalieri appeared first on The American Scholar.

KAMA SUTRA: CLASSIC LOVEMAKING TECHNIQUES REINTERPRETED FOR TODAY’S LOVERS BY ANNE HOOPER

¢50

Don’t be afraid to educate the Dionysian in you,

in your lover. We all have a lot to learn

about pleasure. “How to enjoy it”

should be near the top of this list.

“How to give it” should be up there too.

Think of watching a breeze move through

a flowering dogwood on a bright, hot day.

Think of pouring a bath with huge, shiny bubbles.

Don’t worry about the missing pages.

Instructions are mostly easy to follow.

Believe it or not, you can reach beyond

the skin of your fingertips. You can imagine

being a songbird flying from tree to tree.

Think of this book as a fake book.

Get a candle and a ukulele. Pretend

love has never been made quite right before.

TABLE TOP TILE SAW

$10

Was it 2Pac who said

“Every beautiful thing

contains some kinda pain?”

Maybe it was Red from

that prison-break movie.

A luxury automobile ad?

Truth is: could’ve been

Ms. Colquitt across the street.

She’s a Reiki Master and

says it’s good to get all

out of whack, no joke. Says,

it’s a fool’s dream to hope

for never-ending harmony.

Elsewise, she adds, no feeling

what harmony feels like. So

back to this table top tile saw.

It could contain the next

great je ne sais quoi,

Ms. Colquitt might say,

you just never know. And

that’s the truth, Ruth! Mister

Señor Love Daddy says that.

HALF A GLOBE (THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE)

Free

To spare you the long sad

story explaining what

now seems like complete nonsense,

here’s the short version:

a do-it-yourself fuck-up.

Without a doubt, it could still be—

with much love and patience,

some nerve and imagination—

it could be something yet,

like a salad bowl or the new shade

for a pendant light hanging above

a dreamy kitchen island.

Of course, it’d be wonderful to have

the Southern Hemisphere back.

The equator not so jagged.

The two huge cracks mended.

And to undo the hole

drilled near the North Pole.

You just don’t fuck with magic.

That was the lesson forgotten here.

Forgotten ahead of time.

Forgotten many times.

Just don’t fuck with magic.

Courtesy of Timmy Straw.

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Timmy Straw’s “Brezhnev” appears in our Winter issue, no. 242.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase?

There’s a scene I used to picture a lot as a little kid in the eighties—two people dancing slowly, closely, their bodies seeming to know and anticipate each other, only they are also separated by a screen, so that neither has ever seen the other’s face. This was, I think, one way I understood the world at that time. This dance (so I imagined) is what formed reality itself—Reagan’s America, Gorbachev’s Soviet Union—and the dancers’ mutually blind position was like an engine, driving the world on. This made-up scene, and my adult memory of it, was certainly a major goad to the poem. So was a weird little detail—one of my older brothers could never understand that my one-year-old self was not, in fact, a teenager like himself, and so would read to me from The Annals of Imperial Rome and the most turgid high school astronomy textbooks. Because of his mania for geopolitics, he also taught me how to say “Brezhnev”—so that, awkwardly, the Soviet general secretary’s surname was one of my first words.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? Are there hard and easy poems?

“Brezhnev” was written in late lockdown, at a point when I’d taken to swimming a lot—I had some vaguely science-y conviction that the massively elevated public-pool chlorine levels would be incompatible with covid. I liked to work out poems in the pool (in my head—no waterproof paper was involved), and the first draft of “Brezhnev” had something in it of the satisfying pull of a solid hour of the Australian crawl. It was spookily easy to write, maybe because it is largely narrative, even a little cinematic. The sense was less of pursuing a new poem, with all its hidden laws and strange hostilities, than of becoming increasingly interested in the sequence of images appearing in front of me. In fact, when the first draft was done, reading it back felt a little like looking at a VHS film on pause—the tension and blur of the vibrating image.

But yes, there are definitely poems that are quick to write and poems that can take years! I’m thinking of a poem (“The Thomas Salto”) that started in 2016 and then proceeded through probably fifteen-plus inadequate iterations over six years before arriving, last year, at something I can live with. Poems begin like migraines do, I think, and you get rid of them with similar rigor—albeit not with aspirin, quiet, and a dark room, but by writing and writing them down until they go away (hopefully into their completedness, most often into their failure!).

What were you listening to / reading / watching while you were writing this?

I was reading an essay by the Russian poet Olga Sedakova called “Mediocrity as a Social Danger.” In it, she quotes this luxuriously doomful line from Goethe, which I lifted—“You are a disconsolate guest on this dark Earth.” Sedakova’s essay is audacious, lucid, problematic, and sometimes surly. (At one point she notes, by way of a casual aside, that human will can be summarized as follows: “to ask for or refuse a drink, as on the cross.” To which I reply, Yikes! But also, minus the Christian referent … maybe.)

I was also listening to a lot of Bach (Varvara Myagkova’s recordings of the preludes and fugues) and to Future’s “Mask Off” (the remix, with Kendrick Lamar). I like to think these songs had an effect on the poem’s form on the page, the way interstitial words like and or some are accented through the quickness and harshness of the line breaks—I was particularly wanting to get some of the bare and almost dingy beauty of the counterpoint in Bach’s Fugue in E minor from Book 1, and the skittering play of the snare against Kendrick Lamar’s verse on “Mask Off.”

What was the challenge of this particular poem?

“Brezhnev” is expressly autobiographical, which is not a kind of writing I generally do, and I find it a little scary—not for reasons of “vulnerability” but because such writing is embedded with the impossible imperative to “get it right.” By “getting it right” I mean being true to the dignity of the people—in this case, my family—whom I’ve dragged into the poem, and who know very well the place and time and circumstances of which “Brezhnev” is a (smudged) mirror. If a poem is explicitly autobiographical, then by rights it exists not only for the sake of itself but for the actual, named people in it—i.e., people whom I love and who, while “in the poem,” are also at this very moment out there on earth, doing and thinking and feeling things. All this made me nervous, and so, while the first draft came quickly, I fiddled with subsequent drafts for ages.

I also spent a lot of time sorting out its form—in writing “Brezhnev,” I had begun working in this new way, breaking the line according to a predetermined margin setting such that the emphasis lands, sometimes aggressively, on words that bear no meaning in themselves (and, the). This skews the attention, I think, toward operations and functions in the poem and away from people and things (sort of like shining a spotlight not on the actors and props but on, say, the electrical outlets on the stage floor). I also wanted the poem on the page to invoke a cat’s cradle—the kids’ game that thematizes, with great simplicity, the notion that if you tug on one thing, everything moves. A pretty good summary of Cold War geopolitics, and, I guess, of our own historical moment.

Do you have photos of different drafts of this poem?

I don’t usually keep drafts around, partly out of laziness and partly because I don’t want to look back and turn into a pillar of salt, but I do have an early draft of “Brezhnev.” You can see the three long stanzas, with a couplet overdramatically wedged in there toward the end, plus some unnecessary exposition, the first bit of which I had the wherewithal to remove. The last bit (the final six lines), however, I kept, until Chicu [Srikanth Reddy, the Review’s poetry editor] wisely suggested I redact it. I had wanted a denouement, some pleasing display of concluding truth (whatever that is); but he saw something far more interesting—the torque achieved in its refusal.

An early draft of “Brezhnev.”

Amanda Holmes reads Audre Lorde’s poem “Black Mother Woman.” Have a suggestion for a poem by a (dead) writer? Email us: [email protected]. If we select your entry, you’ll win a copy of a poetry collection edited by David Lehman.

This episode was produced by Stephanie Bastek and features the song “Canvasback” by Chad Crouch.

The post “Black Mother Woman” by Audre Lorde appeared first on The American Scholar.