Colorado could soon pass a law that would effectively allow public colleges and universities to admit more out-of-state students—if they also recruit more high-achieving state residents.

Colorado law currently allows no more than 45 percent of each public institution’s incoming freshmen to come from out of state. House Bill 96—passed by both the House and Senate and now awaiting the governor’s signature—won’t literally increase that cap, but it would raise the limit on the number of in-state students who, by virtue of their status as “Colorado Scholars,” can be counted twice in institutions’ residency calculations, thereby making room for more out-of-state students.

The Colorado Scholars Program applies to state residents who qualify for a specific merit scholarship of $2,500—and who, crucially, count as two in-state students in the calculations that determine whether institutions are in compliance with the nonresident limit. Right now, only 8 percent of Colorado Scholars admitted in any incoming class can double count toward the in-state resident number; the new bill would nearly double that, to 15 percent, creating more space for out-of-state students than admitting in-state students who didn’t qualify for the program would.

Angie Paccione, executive director of the Colorado Department of Higher Education (DHE), said the bill is about more than increasing tuition revenue for schools with high out-of-state demand; it’s also intended to keep Colorado’s best and brightest high school students from leaving. In 2020, nearly a quarter of the state’s high school graduates who went on to pursue a degree did so out of state—5 percent more than in 2009, according to data from the Colorado DHE.

Raising the cap on scholars program recipients, Paccione hopes, will incentivize institutions to aggressively recruit more high-achieving Colorado residents in order to raise the threshold for out-of-state students.

“It’s a war for enrollment right now, and we want to put an end to the brain drain we’re seeing,” Paccione said. “We’ve seen in-state enrollment decline, and we’re trying to shore it up … This is one way to do that.”

Tom Harnisch, vice president for government relations at the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), said Colorado’s efforts to make more room for nonresidents at public institutions follows a general trend, especially in states facing demographic declines that also have high demand from out-of-state applicants, like Wisconsin and North Carolina.

“There are very few states with caps on out-of-state students, and in those states there has been a movement to try and loosen them,” he said. “It’s really an issue in states with popular, well-known public flagships” like the University of Colorado at Boulder—which is pushing up against its state-imposed limits. The university’s newest incoming freshman class was made up of 42 percent out-of-state students, just three percentage points below the cap.

The bill would apply to all Colorado public institutions, but experts say it would only be meaningful for two: Boulder, the state’s public flagship, and the Colorado School of Mines.

Boulder, an R-1 institution located in prime skiing country, has “always been a destination for students from other states,” Harnisch said. Mines, a small but elite engineering university, boasts some of the top energy programs in the country; enrollment there has increased by almost 40 percent since 2010, according to Colorado DHE data.

In total, only 18 percent of undergraduate students attending four-year public universities in Colorado are nonresidents; at Boulder and Mines, they make up over 35 percent of the student population, according to DHE data.

And that number is growing, particularly at Boulder. The new bill would give the institution some breathing room.

“We’ve been calling it the CU bill, because it’s really about Boulder,” Paccione said. “We don’t want CU to become primarily nonresident; it used to be primarily Colorado students, and that’s been changing. But they’re also the only ones with a significant waiting list of out-of-state students, and that’s money sitting on the table right now that could really benefit the institution.”

Colorado State University, in Fort Collins, also boasts a sizable proportion of out-of-state students—about 27 percent in 2021—but for now the bill wouldn’t have much impact there. That’s because Boulder and Mines are two of only three schools that enrolled any Colorado Scholars at all since 2019; the other is Metropolitan State University of Denver, which saw its last class of Scholars graduate in 2021.

Ken McConnellogue, vice president of communications for the University of Colorado (CU) system—of which Boulder is the flagship—told Inside Higher Ed that “the number of nonresident students is not projected to grow but remain in line with the prior year incoming class.”

Cecelia Orphan, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Denver, said even if that were true, the bill would set Boulder up for future expansion of its nonresident student body—and potentially bring it one step closer to securing an end to the state-imposed cap on out-of-state students. She sees House Bill 96 as an incremental victory in a pitched battle between the CU system and state lawmakers reluctant to look like they’re rolling out the welcome mat for out-of-state students at the expense of Colorado taxpayers.

“The Legislature has really held this line that you can only have a certain number of out-of-state students … but Boulder has a strong lobbying presence in the state and has been pushing for that to be removed,” Orphan said. “I’m guessing they got creative and are trying to work a different angle. It’s certainly a more politically palatable approach than just raising the cap.”

Paccione acknowledged that the solution is confusing, further complicating a calculus that effectively obfuscates the true ratio of in-state to out-of-state students. If the bill is signed, Paccione admitted that it could even lead to a situation at institutions like Boulder where out-of-state students outnumber residents in real numbers but still technically fall below the 45 percent threshold.

Double counting Colorado Scholars isn’t the only wrench in the works of the state’s residency numbers. There is also a provision currently in effect that excludes all international students from being counted as part of the out-of-state population—an exemption that could significantly skew data at institutions with international appeal like Boulder and Mines. Another addendum—a provision allowing institutions to count Peace Corps volunteers as in-state students even if they’re nonresidents—was introduced in the new bill.

Harnisch said Colorado is fairly unique in its student residency calculations; he couldn’t think of another state that double counted students for any reason when collecting data.

Michael Vente, director of research for the Colorado DHE, said these special calculations make collecting and tweaking the state’s residency data “one of the most complex” parts of his job.

“We’re doing our best to just follow and interpret the statutes as they’ve been written,” he said. “It can get very complicated based on the carve outs, exceptions and double counting.”

Orphan said the slow but sure push for more out-of-state students is part of a years-long balancing act, wherein Colorado’s higher ed institutions try to offset a lack of public funding by seeking revenue from external sources even as they try to provide more public services to residents.

Out of all 50 states, Colorado provides the second-lowest amount of financial support to public higher education, according to the latest SHEEO data.

“Colorado is a state of Faustian bargains in policy and funding for higher ed,” Orphan said. “What that bargain could mean is, eventually, Colorado residents might have to compete with out-of-state students for spots at our best colleges.”

Paccione said the new bill wouldn’t push out residents.

“This doesn’t mean less room for in-state students,” she said. “Out-of-state students pay a sizable amount of tuition. What that does is that extra tuition helps to fund the in-state students.”

But some are concerned that by trading out-of-state slots for merit scholarship recipients—instead of for students who qualify for Pell Grants or significant financial aid—the state is prioritizing not necessarily the best Colorado students, but the most privileged.

“Merit-based scholarships do typically go to wealthier students, so a lot of these merit-based programs are seen as perpetuating privilege,” Harnisch said. “A lot of people think a better use of taxpayer money would be to focus on need-based aid to bring in students who wouldn’t otherwise go to college.”

Orphan is one of those people. She said that Colorado’s focus shouldn’t be on allowing institutions like Boulder to usher in more out-of-state students, but on making public college more accessible to the state’s marginalized and underserved, who she says have been systemically left behind.

“If we were doing a great job of recruiting Colorado students, making sure they’re prepared through their K-12 education, making college affordable and really had tapped the in-state market dry, then I’d say yes, it’s time to turn to out-of-state applicants,” Orphan said. “But that is not the case.”

After a gunman killed three students and seriously injured five more at Michigan State University on Feb. 13, university officials canceled classes for a week. Students needed time to process and grieve, they said. But after that, everyone was expected to return to their academic routines.

Many students were upset by this decision. A petition started by junior Kameron Cone asking MSU administrators to move to hybrid or online classes for the rest of the semester had garnered over 25,000 signatures as of Thursday night. During the week of canceled classes, MSU’s student newspaper published an editorial assertively titled, “We’re not going to class on Monday.”

“We need more time to process without a class to worry about,” the authors wrote. “MSU must extend the pause they’ve given us so we can decide how we need to proceed to feel safe and secure.”

The university decided to move forward with its planned reopening anyway, welcoming students back on Feb. 20. MSU deputy spokesperson Daniel Olsen said university officials ultimately decided that a familiar routine would help the community recover from the traumatic disruption of the shooting.

“Delaying re-entry after mass violence events can lead to avoidance and disrupt recovery,” he wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “We also talked with other schools who had been through similar tragedies, and they experienced something similar to what we did—that is that many students were feeling strongly that they wanted to come back.”

At the same time, faculty members say officials have granted them significant flexibility in running their classes and have encouraged leniency in grading and workload. On the Friday before classes resumed, interim provost Thomas Jeitschko asked professors in an email to “extend as much grace and flexibility as you are able.”

Becca Smith, president of the American College Counseling Association, said that in the wake of a campuswide tragedy, institutions shouldn’t wait too long to reintroduce academic life. At the same time, it’s vital that they don’t move on too quickly and force students back into situations that could be retraumatizing.

“That routine does help give a sense of, ‘We’re going to be OK.’ But it’s also important to take time to sit with the fear and grief and not avoid that and pretend like everything is normal,” she said. “It’s a struggle to find that balance.”

Dhriti Marri, an MSU sophomore, lives in a dorm across the street from the Student Union building, a popular hub of student activity with a food court and classrooms, and one of two buildings where the shootings took place. She usually goes there every night to get food, but she had eaten elsewhere that evening. From her dorm room window, she saw students rushing away from the building.

“I thought, something has got to be wrong,” she said. “I’d never seen people run like that.”

She and her roommate spent the next four hours barricaded in the room; at one point a SWAT team swept through their hall. Once the lockdown was over, Marri went home to her family, who live about an hour away, to recover for a few days—a period she says she barely remembers. Returning to campus, she noticed a pervasive sense of unease.

“Going back into a classroom is very weird,” she said. “I’m so hyperaware of little things—noises, like a door slamming, make me jump. I always make sure I know where the exits are.”

MSU officials didn’t want to make students revisit the sites of the shootings: the Student Union and Berkey Hall, where the three killings took place, have been shut down for the remainder of the semester. Hundreds of classes normally scheduled in those buildings have been relocated, some to rooms that are not traditionally used for classes.

But many students balked at the idea of returning to learning in any building. The trepidation and backlash MSU unleashed with its decision to resume classes after a week illuminates a difficult question that U.S. universities are increasingly being forced to answer: After a campus shooting, how much time off is enough?

Different institutions have reached different conclusions. Students at the University of Virginia, for example, returned to in-person classes just two days after a campus shooting last November in which three students were killed and two injured, all members of the UVA football team. But at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, after a shooting left two students dead in May 2019, university leaders canceled all classes for the remainder of the semester, as well as any final exams.

Smith said there’s no ideal amount of time to give students off after a campus shooting; the answer varies depending on the size of the institution, the timing of the semester and the advice of each institution’s mental health experts. But whatever the situation, she said, a return to campus can’t be delayed indefinitely.

“You can delay classes for a week or two, but eventually you start running into other problems: graduation, jobs, internships, all of that is affected … the world outside keeps moving, and students are part of that world,” she said. “The mental health side is important, but there’s also academic integrity to take into account, so it’s complex.”

Of course, Smith added, the fact that so many campuses have had to grapple with this question in the first place reflects the uniquely American problem of gun violence and mass shootings, and their impact on the country’s youth. There’s a sense of helplessness, she said, in being called on to mediate student reactions to such tragedies rather than address their cause.

“Since the Virginia Tech shooting and what happened at Northern Illinois University back in 2007 and 2008, I think higher ed has done a really good job trying to improve threat assessment and shooting response at the campus level,” she said. “But a lot of these campuses, whether they’re in urban or rural areas, are open, accessible spaces, like malls or movie theaters, and I don’t know what more we can do on our level, because ultimately, it comes down to politics and the concerns around gun accessibility that keep coming up after every shooting.”

![]() Officials at MSU have undertaken a number of efforts to address the mental health needs of the nearly 50,000 enrolled students as they pour back onto campus, including hosting therapy dogs and organizing vigils and memorials for the victims.

Officials at MSU have undertaken a number of efforts to address the mental health needs of the nearly 50,000 enrolled students as they pour back onto campus, including hosting therapy dogs and organizing vigils and memorials for the victims.

Olsen said that in the two weeks following the shootings, MSU counselors and the community mental health providers who volunteered to help meet the overwhelming need for student support had 3,000 “touch points” with students and 2,300 with employees. Those touch points included individual consultations, group counseling sessions and outreach events on campus.

Melanie Bennett, senior risk management counsel at the insurance company United Educators, said they recommend their members be “clear and consistent” in messaging and policies after a campus shooting or other traumatic event. But most important, she said, institutions should balance clear-eyed decision-making with empathy and openness toward student needs.

“Our policy here is ‘cool heads, warm hearts,’” she said. “It basically means while you’re supporting the community, you’re also taking a broad look at procedures and policies on campus to make sure everything is in place that should be.”

Marri said that while returning to campus so soon was difficult, she was ultimately relieved to be back in the place she considers a second home, where many of her peers can relate to her experience.

“I did need that week off to process and just get used to whatever my new normal was going to be,” she said. “But I think I did need to go back and be around people that went through the same thing, who share that grief. That was really helpful.”

At a Feb. 17 press conference, Jeitschko, the provost, said faculty would rework their syllabi for the rest of the semester, lightening the course load and postponing upcoming exams.

“I’d like to emphasize that no one thinks that we’re coming back to a normal week,” Jeitschko said at the press conference. “In fact, this semester is not going to be normal.”

Marri said that most of her professors offered flexibility and understanding. Only one of her classes required students to attend in person, and the vast majority of her exams and assignments were postponed.

All MSU students were also given a credit/no-credit option for any class, allowing them to complete courses for credit without low grades affecting their overall GPA. Olsen wrote the decision was meant to “give survivors choice and control over their recovery process” and enshrine the flexibility they were asking of faculty “at the institutional level.”

“Students will have the entire semester to make that decision,” he added.

Smith, who is also the director of counseling at Berry College in Georgia, said the online and hybrid learning options many institutions developed during the COVID-19 pandemic have made it easier to comply with student and faculty requests for flexibility after a tragedy like the MSU shooting.

“At the start of the pandemic, universities were really scrambling to get online, but now we know institutions and faculty can move to an online or hybrid system smoothly,” she said. “That really allows you to be more flexible and meet student needs on a case-by-case basis.”

Phillip Warsaw, a professor in MSU’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, has taken advantage of that flexibility. He said that while there was “very little appetite” among MSU faculty members, himself included, to return to mandatory hybrid and online learning, it’s a helpful short-term option in this case. About half of his students are taking his classes remotely, he said; he also moved all deadlines back until after spring break, which ends today.

“There was a clear sense that coming back fully in person the following week was just not going to be viable,” he said. “Having that flexibility was something all of my students indicated they needed.”

Smith noted that institutions shouldn’t underestimate how drastically mental duress can impact learning.

“Your brain changes through trauma and that acute stress. I mean, it’s so hard to focus, to pay attention and learn,” she said. “Huge institutions thrive on their rigidity; they aren’t used to being flexible. But I think in these situations, you really have to be.”

Early last month, the University of North Carolina system’s Board of Governors approved a ban on “compelled speech,” preventing colleges from requiring prospective students or employees to “affirmatively ascribe to or opine about beliefs, affiliations, ideals or principles regarding matters of contemporary political debate.”

The vote was taken in response to an application question that North Carolina State University introduced in 2021, which asked applicants to affirm their commitment to “building a just and inclusive community.” N.C. State removed that question a few days before the board’s vote.

Nathan Grove, a chemistry professor at UNC Wilmington and the chair of the campus’s Faculty Senate, said that vote served as a wake-up call for him and his colleagues. They saw it as a sign that the Board of Governors, which was “usually pretty hands-off,” he said, could take “a more heavy-handed approach” on certain issues. Worse, Grove said, the decision was based on a misunderstanding.

“We don’t ask politically charged questions in our interviews. We just don’t,” he said. “Are we interested in hearing about how you view reaching out to underserved populations of North Carolina? Yes, we are. But that’s also a big concern for the system.”

Art Pope, a member of the Board of Governors since 2020 and a prolific Republican donor, denied that the compelled speech vote was motivated by politics.

“To say that a statute banning political speech requirements is part of a political agenda is absurd,” he told Inside Higher Ed. “It is anti-political; it is protecting the rights of employees, including university faculty, so they cannot be compelled to subscribe to a political ideology.”

Jane Stancill, the system’s vice president for communications, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed that the “policy revision” banning compelled speech is “content neutral.”

It’s not the first time the board has drawn cries of partisan overreach. In 2015 it shut down a center on poverty and opportunity at UNC Chapel Hill, whose director was a vocal critic of conservatives, along with two other centers: one for environmental science, at East Carolina University, and the other dedicated to social change, at North Carolina Central University. In 2017 the board barred Chapel Hill’s Law Center for Civil Rights from filing litigation, a move that essentially shuttered the center and which its director called “an ideological attack.”

Holden Thorp, who was chancellor at Chapel Hill from 2008 to 2012, said the idea that such moves are not motivated by politics is “ridiculous.”

“I find it frustrating that they're trying to paint it as if its not part of a political force. Of course it’s political; it's always been political,” said Thorp, now editor in chief of Science. “But UNC has a proud tradition. They’re trying to make it seem like nothing is changing when it clearly is.”

What’s changing, the board’s critics assert, is that the overt politicization of higher ed, starkest in Florida and Texas, has spread to the Tar Heel State, where years of partisan contention between lawmaker-appointed board members and campus constituents have laid the groundwork for a heightened battle over issues like diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and critical race theory.

But North Carolina, as many sources who spoke with Inside Higher Ed pointed out, is not Florida. For one, it is a far purpler state, with a Democratic governor and, as of 2020, more registered Democrats than Republicans on its voter rolls. Lawmakers are also highly invested in the state’s higher ed institutions; Thorp stressed that any move that could destabilize UNC is not taken lightly by lawmakers of either party.

“Without UNC, the economy of North Carolina would not be what it is, and they don’t want to endanger that,” Thorp said. “When they tried to pass the [2016 anti-transgender] bathroom bill, for example, all hell broke loose and they had to walk it back.”

Still, recent actions taken by the Board of Governors, like the compelled speech ban, point to a growing boldness around hot-button political issues. As tensions rise in an increasingly polarized national debate around higher ed, the UNC system appears to be at a crossroads.

Paul Fulton, a former member of the Board of Governors from 2009 to 2013, said he doesn’t think UNC has quite reached the tipping point, but he is increasingly concerned about the future of what he calls “one of our state’s greatest assets.”

“We’re a resilient system, and we’re nowhere near the Florida or Texas level [of political influence],” he said. “But we do have a hint of that nowadays. And it is worrisome.”

UNC Chapel Hill, the system’s flagship, has frequently found itself at the center of debates about political interference. In 2021, trustees tabled a scheduled tenure vote for Pulitzer Prize winner Nikole Hannah-Jones over her leadership of The New York Times’ “1619 Project.” Last month, a directive from the Chapel Hill campus’s own Board of Trustees to fast-track a new School of Civic Life and Leadership reignited the conflict between trustees and faculty members.

But system at large has recently come under fire over similar concerns, well before the compelled speech ban. Last March, the Association of American University Professors released a report detailing its concerns about partisanship and political overreach in the UNC system at large—not just Chapel Hill, but Appalachian State University, Fayetteville State University and East Carolina and Western Carolina Universities.

The AAUP went beyond its usual censure and “condemned” the entire system for “mounting political interference in university policy.”

On Feb. 21, the Commission on the Governance of Public Universities in North Carolina held the first of a planned series of public forums. Governor Roy Cooper, a Democrat, launched the commission in November to examine “instability and political interference” brought on by the system’s Board of Governors and campus Boards of Trustees.

Kimberly van Noort, the system’s senior vice president for academic affairs and current interim chancellor at UNC Asheville, pushed back on the AAUP report, writing that it was a “relentlessly grim portrayal of one of the nation’s strongest, most vibrant and most productive university systems.”

North Carolina has not gone as far as Florida, where Governor Ron DeSantis has engaged in a protracted takeover of the state’s higher education system, from banning DEI offices to installing loyalists on the New College of Florida’s Board of Trustees, all with the openly political goal of fighting “woke activism.”

Still, worries abound that partisan infighting, however contained, could have detrimental effects on UNC campuses. Grove said political tensions have gotten much worse since he started teaching at UNC Wilmington 13 years ago and are a “major distraction” from pressing practical issues.

“Every time you’re having a conversation about DEI or compelled speech, for example, you’re not having a conversation about affordability and accessibility,” he said.

He also worries that the partisan influence could usher in a period of decline and brain drain for the system, whose faculty and staff turnover rates doubled in 2021.

“The more that we focus on hot-button issues and enact policies that respond to those, we’re going to have a harder time attracting and retaining faculty,” he said. “My colleagues and I all know people in Texas and in Florida that see the writing on the wall, and they’re getting out, because that’s not an environment that is supportive of their work. I would really hate to see that happen here.”

UNC’s 24-member Board of Governors is entirely appointed by members of the state’s Republican-majority General Assembly. Rob Anderson, president of the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed that such appointments are unique in that “most similar structures involve appointment or approval by a state governor.” But it’s been that way in North Carolina for over half a century.

The appointment process for campus Boards of Trustees, however, was recently changed. In 2016, shortly after Cooper was elected governor, the state Legislature voted to strip him of his traditional four appointments to each campus board and give them to the Legislature.

This angered faculty members across the system, many of whom said it was a calculated move to deprive the first Democratic governor since the 2010 Republican takeover of his influence on UNC governance. Regardless of intent, faculty and former system leaders who spoke with Inside Higher Ed said it was symbolic of the political tug-of-war they believe has defined much of UNC’s contentious governance since.

Last May, for instance, legislators voted to uproot the UNC system’s headquarters from its longtime home in Chapel Hill and relocate it to the capital, Raleigh. The move had been debated for years, but the board’s decision to abruptly relocate it to a rented office in Raleigh while awaiting construction of its new building earned it critics even within the Board of Governors itself; former board member Leo Daughtry, a longtime state GOP leader, said it was another attempt to consolidate power by putting system leadership under the watchful eye of the General Assembly.

Anderson said that regardless of lawmakers’ involvement, system leaders were responsible for “cultivating trust” above and beyond partisan allegiance. North Carolina, in his view, has so far succeeded in this regard. ![]()

It’s a task that many say has become more difficult as higher ed has moved firmly into the national political spotlight. Thorp said the threat of partisan interference from board members and state lawmakers has gotten “way more serious” since he left Chapel Hill.

“I’m just glad I’m retired,” said Thorp, who left his final higher education job, as provost at Washington University in St. Louis, in 2019. “It’s miserable dealing with all of that.”

Thorp, who was appointed by former system president Erskine Bowles, a Democrat, in 2008, said navigating political dynamics has always been part of the job, albeit a frustrating one. He resigned as chancellor in 2012, after mounting pressure over scandals in the athletic department, but said the board’s political shift after Republicans won the legislature in 2010 “had a big impact on what happened with me.” His successor, Carol Folt, resigned in 2019 after clashing with the board over her decision not to re-erect a Confederate monument known as “Silent Sam” that was toppled by protesters.

“We’ve seen massive turnover at the highest levels, at Chapel Hill but also at the system level, and it was basically all for political reasons,” said Fulton, who also sat on the Chapel Hill Board of Trustees from 2001 to 2009.

Former system president Tom Ross, who is now helping to lead Governor Cooper’s commission on governance, was pushed out in 2015, and many onlookers suspected political disagreements played a role in his ouster. Even his successor, former Bush administration education secretary Margaret Spellings, left in 2019 amid grumblings that she was not sufficiently conservative for the board.

Two years before her departure, Spellings was chastised by a majority of the Board of Governors for her handling of the controversy over whether to take down the Silent Sam monument, before it was brought down by demonstrators. The board’s main objection was that she reached out to Cooper, a Democrat, for advice.

Spellings, who was named co-chair of Cooper's commission on governance along with Ross, did not respond to Inside Higher Ed’s request for comment in time for publication, citing a schedule issue.

Fulton, who describes himself as a “lifelong Republican,” said things were different when he sat on the Board of Governors.

“I didn’t really know the political affiliation of most of my colleagues there,” he said. “Politics didn’t really play into our work then. But now it’s pretty darn partisan, and I think that’s reflected in a number of actions [the board] has taken recently.”

He said the best way to combat that is to “depoliticize” the selection process for board members, from campus trustees to the Board of Governors. To that end, he said he hopes the current board and the legislators who appointed them “listen carefully and seriously” to the recommendations of Cooper’s commission on governance.

"We have to look at the appointment process," he said. "If it isn't depoliticized, I'm afraid the system will be significantly and permanently diminished."

Pope, the Board of Governors member, said he’d be listening in on the commission’s public forums with interest via Zoom. But in terms of implementing changes, the ball remains firmly in the hands of Republican lawmakers.

“The governor is entirely within his right to establish this commission and explore recommendations, but it has no force of law behind it,” he said. “The most Cooper’s commission can do is try to persuade the Legislature.”

After a long period of funding cuts and stagnation, public higher education in New York state got an infusion of hope last year when Governor Kathy Hochul proposed a historic funding increase, allocating $8.5 billion—including $1.5 billion in new funding—to the State University of New York and City University of New York systems.

In her latest budget proposal for fiscal year 2024, the Democratic governor pledged $7.5 billion, slightly less than FY2023. She has said that her five-year funding plan aims to be “transformative” for the state’s public higher education institutions, with the ultimate goal of getting two-thirds of New Yorkers a postsecondary credential.

Fred Kowal, president of the United University Professions, SUNY’s faculty union, said the leadership transition has opened up possibilities for state support that simply didn’t seem possible under former governor Andrew Cuomo, whose nearly 10-year tenure ended in 2021 amid sexual misconduct allegations and under whom the state’s higher education budgets were often on the chopping block.

“Governor Cuomo didn’t value SUNY … he shifted the model pretty extensively towards a dependence on tuition, fees, room and board, and state commitment was pretty much flat throughout his whole tenure,” Kowal said. “Governor Hochul has a completely different attitude.”

This shift, Kowal said, comes at a precipitous moment for the state’s colleges and universities.

But many leaders and faculty members at New York’s public higher ed institutions also say the increased support isn’t enough to pull them out of the financial pit created by years of state cuts and disinvestment. Before making SUNY and CUNY “leaders in global higher education,” they say, Hochul must first make up for the damage done under her predecessor.

“Transformation is only possible once you’ve achieved financial stability,” Kowal said. “We need to make up for years of cuts and neglect before we can get there.”

Institutional leaders have cheered the budget boost. Both the SUNY and CUNY chancellors extolled the “historic” increase and the good it would do for their systems.

Stephen Kolison, president of SUNY Fredonia, which is currently operating with a $16 million deficit, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed that he was “pleased” with Hochul’s “unprecedented support to advance SUNY’s vision.”

But many faculty, staff and union leaders in the state’s public higher ed systems are more measured in their praise, saying that while the much-needed infusion is a step in the right direction, it’s not nearly enough to overcome decades of disinvestment and cuts.

“Going back to the great recession, we’ve seen massive cuts that were never really made whole,” Kowal said. “This new funding brings an end to austerity, but it falls short of what these campuses need to grow and survive.”

Hochul’s plan would not create a separate or targeted funding mechanism for the most financially challenged campuses, Kowal said, and the funding boost also comes with the caveat that institutions raise tuition, a move students and faculty have decried.

In an email to Inside Higher Ed, Buffalo State University president Katherine Conway-Turner, whose institution is also facing a $16 million deficit, applauded Hochul’s proposal while highlighting her campus’s ongoing fiscal struggles.

“After years of state budgets that kept SUNY funding flat, [Hochul] has made higher education one of her priorities since she took office,” Conway-Turner said. “Still, we’re facing financial challenges … We know we can begin to reverse some of these declines through new initiatives.”

Kowal said that’s especially true for institutions that have been disproportionately affected by cuts over the years and are now “facing severe financial challenges.” Those include SUNY campuses at Fredonia, Potsdam, Canton and Plattsburgh, in addition to Buffalo State, all of which are operating with deficits of more than $5 million.

Some of those institutions have begun using the funding boost from last year to hire more faculty and chip away at their deficits, Kowal added, but “most aren’t feeling the effects yet. They’re just too deep in the hole.”

James Davis, president of the Professional Staff Congress (PSC), CUNY’s faculty and staff union, accused Cuomo of being antagonistic to public higher education in New York and to CUNY in particular. Adjusted for inflation, state aid to CUNY fell by more than 5 percent since 2011, when Cuomo first took office. In 2016, Cuomo attempted to slash the CUNY budget by $500 million and only reneged after facing public backlash; in 2020 he was poised to make even more significant cuts before his ouster.

By contrast, Hochul’s FY2024 budget proposal includes $94 million in new funds for CUNY. Among other things, that money would help institutions fill in the so-called “TAP gap” between what tuition costs and what the state contributes through the Tuition Assistance Program (TAP), allowing them to make some much-needed faculty hires.

But Davis said the damage done over the past few decades is greater than the state can realistically make up for through one-cycle infusions of support.

![]() “Last year was a favorable turnaround. The issue is, there’s so many years of disinvestment to try to offset that any one budget cycle is not going to cut it,” he said.

“Last year was a favorable turnaround. The issue is, there’s so many years of disinvestment to try to offset that any one budget cycle is not going to cut it,” he said.

To make matters worse, he said, the city government, which is responsible for about 40 percent of CUNY funds, is set to cut its budget for the system next fiscal year.

As a result, CUNY ordered all campuses to implement a hiring freeze and slash their budgets by at least 5 percent; those with negative budgets will have to cut more. It doesn’t help that enrollments have fallen by over 10 percent across the system since 2019.

Some CUNY campuses are struggling more than others, Davis said—especially the system’s seven community colleges and four-year institutions that primarily serve students of color. That’s largely because CUNY has become more tuition-dependent as the TAP gap has widened over time, and institutions with more high-need students have had to spend more to fill in that gap.

Davis said this disparity is clearest in faculty-student ratios at institutions that have had to prioritize tuition assistance over making new hires.

“The greater the proportion of students of color on our campuses, the less likely they are to have access to full-time faculty,” he said. “That’s often the difference between somebody persisting to get their associate degree or their bachelor’s.”

Eighty-five percent of students at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn are Black, the highest of any CUNY campus; the college also has some of the worst retention rates in the system. In 2015 its graduation rate for both two-year and four-year degrees was under 20 percent—more than 40 percent lower than the national average for public institutions.

“Students often have to work full-time, and in order to be eligible for maximum tuition, they have to be enrolled as full-time students, which is a very difficult balance,” said Esther Llamas, an academic student support program specialist at Medgar Evers. “On top of that, wraparound services the students really need”—like academic support, childcare and mental health counseling—“just aren’t there like they used to be.”

Susan Kang, a professor of political science at CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is no stranger to what she calls the “age of austerity” for New York public higher education. When Cuomo recommended cutting the CUNY budget by almost half a million dollars in 2016, a seven-months-pregnant Kang was arrested protesting in front of his office in Albany.

And while she acknowledges gains have been made under Hochul, she also believes a new kind of austerity is setting in.

“I’ve been here for 15 years, and I’ve only ever worked under a period of austerity and belt tightening,” she said. “We had a good year last year with state funding, but now we’re in a new age of austerity, a kind of pre-emptive austerity … it’s a question of funding priorities, seeing who the mayor and the state really want to serve.”

The solution, Kang, Llamas and Davis agreed, is a long-term funding plan to get CUNY back on track, erase the deficits of its most troubled institutions and—eventually—restore the system’s initial promise of free tuition for all students. That plan is the “New Deal for CUNY,” legislation touted by the PSC that would provide $1.7 billion in new funding for the system over the next five years. Advocates say the ambitious bill is a long way from being passed, but that progress is easier under the new governor.

“We know it’s a big-ticket ask, but we’ve been able to expand the number of sponsors on the bill and gain a lot of traction in both chambers of the state Legislature,” Davis said.

Llamas recently returned from a lobbying trip to Albany, where she and a cadre of supporters promoted the New Deal for CUNY plan to lawmakers.

“I definitely believe there’s been a promising shift,” she said.

College completion rates of Black students are lower than those of any other ethnic or racial group: 34 percent of Black Americans have an associate degree or higher, compared with 46 percent of the general population, according to a recent report from the Lumina Foundation.

The reasons for this attainment gap are varied, but Black students say the biggest obstacles they face are cost, a lack of extracurricular support and “implicit and overt forms of racial discrimination,” according to a new joint study by Lumina and Gallup.

“We’ve seen Black student enrollment and completion declining over the last 10 years, and it continues to decline post-pandemic,” said Courtney Brown, Lumina’s vice president of strategic impact and planning. “This study is important because it begins to tell us why—not from experts on the outside but from students themselves.”

The study is based on a survey that asked more than 6,000 currently enrolled students—including 1,106 Black students—about the challenges they face in higher ed that make degree completion difficult. The survey found that Black students are far more likely to experience racial discrimination than their non-Black peers, and those enrolled at less diverse institutions reported experiencing discrimination more often.

It also found that Black students are more likely than any other group to have a full-time job or significant family caregiving and wage-earning responsibilities—factors that they indicated make it difficult to succeed in college.

Shaun Harper, executive director of the Race and Equity Center at the University of Southern California, said the results were disheartening but not surprising.

“The data are painstakingly clear: Black students are underserved in higher ed,” he said. “Very few institutions have a Black student success strategy … Until and unless there’s actual institutional strategies with key performance indicators and accountability metrics, we’re going to continue to see, in report after report, these gaps in Black student success and attainment.”

Brown said one major takeaway from the survey is the importance of cultural inclusion and antidiscrimination efforts in closing the achievement gap for Black students across all types of institutions and programs.

“There are a number of material things that can be done to make college success more achievable for Black students—financial aid, tuition reductions, support for childcare—but that’s not the only answer,” she said. “It’s cultural, too. The survey really shows that discrimination is a big issue.”

![]()

According to the report, 21 percent of Black students said they felt discriminated against “frequently” or “occasionally” in their program, compared to 15 percent of all other students. Those enrolled at institutions with the least racially diverse student bodies were nearly twice as likely to say they felt discriminated against as those at diverse institutions; they were also more likely to say they felt physically or emotionally unsafe on campus.

The study found significant disparities by program and institution in the level of discrimination Black students faced. Those at private nonprofit colleges and universities said they were more likely to experience discrimination (23 percent) than those at public institutions (17 percent). In addition, students enrolled in short-term credential programs and for-profit institutions reported more discrimination than those enrolled in bachelor’s or associate degree programs at private nonprofit or public institutions.

Brown attributes the disparity to a variety of factors. For one thing, Black students are more likely to attend for-profit colleges than any other group; as of 2018, they made up 21 percent of for-profit students but just 13 percent of the students at nonprofit and public four-year institutions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Black students are more likely to be exploited by and indebted to for-profit colleges than other groups—a potential symptom of discrimination or lack of support for students with unique material and cultural needs.

Meanwhile, short-term credential programs are populated largely with—and taught mainly by—white men, Brown said.

Black students “are walking into an environment that is predominantly white, older, male, that is likely not welcoming, that likely has outdated curriculum with instructors that don’t look like them or can’t mentor them,” she said. “They don’t feel like they belong.”

Harper said that while the conversation around discrimination on campus and the rise of antiracist policies has exploded since the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020, not enough institutions have taken action.

“Recently, more people in higher ed are talking about antiracism … but to continue to do nothing to better serve Black students is also a kind of racism,” he said.

For many demographic groups, enrollment and attainment declines have been tied in part to growing doubts about the value of higher education and a sense that alternative pathways to economic stability are less expensive and just as effective. But Brown said that while the opportunity cost of going to college is a major factor in the attrition rates of Black student, skepticism about higher ed’s value is not.

“Those that value [higher ed] the highest are people of color: Black students, Latino students, way higher than white students. So that’s not the issue here,” she said. “It’s the in-the-moment needs, thinking, ‘I have to take care of my family and so I have to make money.’ It’s a question of priorities.”

The survey found that 35 percent of Black students in the U.S. have major life responsibilities beyond coursework, and 22 percent are caregivers for children or adult family members, double the average for other student groups. In addition, 20 percent of Black students in four-year programs were balancing coursework with a full-time job—twice as many as all other bachelor’s candidates.

![]()

Addressing the completion gap, then, Brown said, doesn’t call for making a stronger pitch to Black students about the benefits of higher ed; rather, it requires committing to material support that can help make two or four years in college feasible for those who are low-income.

“The pandemic created all kinds of issues, and one is that people could get a job making more money than they would pre-pandemic,” Brown said. “These are low-wage jobs that aren’t going to last or create generational wealth … but if you can make $15 or $20 an hour, it’s hard to stop doing that to enroll in a degree program when you’re responsible for taking care of your family.”

Some helpful first steps would be to increase childcare options and need-based scholarships, open food pantries, and offer flexible class delivery methods, Black students said in the survey. Flexible classes were deemed especially important; 47 percent of Black respondents said having the option to go remote or hybrid was “very important,” compared to 29 percent of other students.

“Institutions need to meet their students where they’re at, and that has to include Black students,” Brown said.

Harper has been working for years on an unpublished research project to calculate revenue losses from Black student attrition rates at public colleges and universities. He said that even before the pandemic and the impending “demographic cliff,” the failure to retain Black students has cost institutions dearly.

“In addition to failing these students, institutions fail themselves financially when they don’t create the conditions that lead to more Black students persisting and completing, because when [students] leave, they take their tuition payments, Pell Grants and student loans with them,” said Harper, who is also a professor of business and education at USC. “The consequence, for many institutions, is millions of dollars every year.”

That cost may multiply in the years to come, Brown said, as the long-anticipated demographic cliff approaches and college-age Black students—whose population is increasing, along with other groups of students of color—become a crucial demographic for institutions facing enrollment declines.

Brown said she hopes the survey offers some clarity and context to the retention gap for Black college students and drives a response beyond words.

“This data really gives us a glimpse into some things that can be done, rather than guessing,” Brown said. “Institutional leaders and policy makers need to look at these results and say, ‘We have to do better, and here are areas we can address immediately.’”

Jhenai Chandler, director of college completion at the Institute for College Access and Success, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization focused on affordability, accountability and equity in higher ed, said the report shows the reality of the Black student experience and its challenges—a reality that she said is often ignored by institutions and policy makers.

“We feel as a country that segregation was so long ago, but it wasn’t; the effects of that are still really being felt by these current generations,” she said. “Institutions need to make sure they’re addressing those issues that can really stop high-performing, capable students from completing their education.”

State fiscal support for public higher education institutions is up 6.6 percent for fiscal year 2023, according to the latest report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, or SHEEO.

It’s the second year in a row that overall state funding for higher ed has risen significantly, according to Sophia Laderman, SHEEO’s associate vice president, who attributes the trend in part to state budget surpluses and federal stimulus funding.

State support increased in 38 states, jumping by 10 percent or more in 14 states. Funding decreased in just five states and Washington, D.C., according to the report.

Laderman said that because SHEEO’s data don’t account for inflation, they usually show at least some year-over-year increase in state funding. Still, she said, this year’s numbers are “definitely a strong positive,” building on a strong fiscal 2022, which already represented some of the largest boosts for state higher ed funding since the 2008 recession.

“I think it’s a sign that we’re continuing to work towards restoring prior levels of funding for higher education,” Laderman said. “I would say it’s more positive than we’ve seen in the last two decades.”

For the past two years, SHEEO has also tracked data on the COVID-19 federal stimulus funds that states allocated to higher education. In FY2023, states spent $1.2 billion of federal funding on higher ed.

Laderman said the federal stimulus funding is partly—but not fully—responsible for the overall increase. She thinks states have also responded to concerns about college affordability by granting funding requests attached to promises for a tuition freeze—as state lawmakers did in Tennessee and are contemplating in Texas—or to help with financial aid in general.

“It’s definitely in large part due to federal stimulus, both the money that’s gone right to higher ed and the federal funding that’s flowed to states in general, which has given their budgets a lot more support and made them not have to make difficult decisions that often resulted in cutting higher ed,” she said. “It’s hard to say how much of this is due to federal stimulus funding versus states prioritizing higher ed. I’d like to optimistically think it’s a little bit of both.”

Some of the states with the most significant growth in state support include Mississippi (26.6 percent), New Mexico (23.5 percent), Tennessee (22.1 percent) and Arizona (19.8 percent).

Laderman said that in some states, like Arizona and Colorado—which saw a 44 percent and 118 percent increase in funding over the past two years, respectively—the boost is making up for a dip in funding since the early days of the pandemic, filling in with state money the gaps that federal aid had covered in 2020 and 2021. In other cases, such as Tennessee and New Mexico, public institutions have been steadily receiving funding boosts for years.

California public institutions received the largest amount of state support, nearly $21.3 billion. Despite a budget deficit last year, Governor Gavin Newsom followed through on his promise to raise the state higher ed budget 5 percent each year if the state systems met certain targets for enrollment and retention.

“We really were breathing a sigh of relief when we saw the governor’s January budget proposal for higher education, especially given the size of the budget shortfall,” said Jessie Ryan, vice president of the California-based nonprofit advocacy group Campaign for College Opportunity.

Nearly half of all state funding in FY2023 funding went to four-year institutions, while two-year colleges received 22 percent of support; another 13.2 percent went to financial aid and 11.4 percent to research, hospital expansion and medical schools, according to the SHEEO report. California was one of the few states to allocate more support for two-year colleges than four-year institutions—$8.4 billion and $7.8 billion, respectively.

Among the states where overall funding decreased, Connecticut’s decline was the most dramatic, down 9.2 percent from the last fiscal year, according to the report. Laderman said it was one troubling mark in an otherwise promising survey.

“Connecticut is the only state I’m really concerned about right now,” she said.

But Benjamin Barnes, chief financial officer for the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities system, said the SHEEO data don’t reflect the realities in Connecticut. The report lists the state’s total funding at $1.28 billion, including $40 million in federal stimulus finding, down from nearly $1.4 billion last year. Barnes said that doesn’t take into account a number of additional allocations of federal aid money for higher ed, including several hundred million dollars from the American Rescue Plan Act doled out at the end of 2022 and another $100 million from a labor settlement.

“I don’t think this accurately reflects the state’s contributions to public higher education,” Barnes said. “I think that’s probably just an artifact of the Byzantine way the state of Connecticut budgets.”

Barnes said Connecticut has “really stepped up” during the pandemic to help its public institutions by doling out short-term infusions of funding. The big question now, he said, is whether it’s sustainable after the federal stimulus dries up.

“We are in active discussions with [state lawmakers] about making some of the one-time funding that we’ve received in the last couple of years permanent,” he said. “We need to strengthen the state’s long-term commitment to public higher education.”

Laderman said that in light of persistent economic uncertainty and rising inflation, the overall upswing in state funding over the past two years has surprised her, even with the influx of federal pandemic aid. She’s cautiously hopeful that states will continue the trend.

“What a lot of people, including myself, would have expected for state funding to do in these most recent years is actually to decline,” she said. “The fact that it’s increasing anyway, I think, is really positive.”

| State | One-Year Change, State Support Only | One-Year Change, State Support and Federal Stimulus | Two-Year Change, State Support Only | Two-Year Change State Support and Federal Stimulus | Five-Year Change, State Support Only | Five-Year Change, State Support and Federal Stimulus |

| Alabama | 6.5% | 6.5% | 19.3% | 19.3% | 33.0% | 33.0% |

| Alaska | 10.5% | 9.7% | 8.9% | 3.2% | -4.2% | -4.2% |

| Arizona | 19.8% | 19.9% | 44.0% | 27.0% | 59.0% | 59.1% |

| Arkansas | 1.4% | 1.4% | 9.1% | 7.7% | 12.0% | 12.0% |

| California | 6.4% | 5.1% | 25.0% | 24.6% | 48.2% | 48.2% |

| Colorado | 9.6% | 1.0% | 118.6% | 15.5% | 48.5% | 48.5% |

| Connecticut | -9.2% | -7.6% | -8.1% | -5.8% | 1.5% | 4.8% |

| Delaware | 3.8% | -9.1% | 5.0% | -10.5% | 15.8% | 15.8% |

| Florida | 7.0% | 6.6% | 10.5% | 10.0% | 23.4% | 23.4% |

| Georgia | 12.7% | -4.6% | 26.0% | 25.1% | 31.8% | 32.0% |

| Hawaii | 10.1% | 12.0% | 5.5% | 10.7% | 17.8% | 25.1% |

| Idaho | 8.0% | 14.9% | 11.9% | 19.1% | 23.9% | 34.6% |

| Illinois | -0.3% | -0.3% | 8.9% | 8.5% | 28.6% | 29.7% |

| Indiana | 1.5% | 0.2% | 7.4% | 7.3% | 7.8% | 8.4% |

| Iowa | 2.0% | 1.7% | 4.4% | 3.8% | 9.5% | 10.1% |

| Kansas | 9.2% | 10.3% | 19.1% | 6.3% | 29.4% | 30.7% |

| Kentucky | 11.6% | 14.6% | 21.4% | 19.9% | 21.3% | 24.9% |

| Louisiana | 9.0% | 8.2% | 30.1% | 20.1% | 27.8% | 28.3% |

| Maine | 9.4% | 8.9% | 14.1% | 13.3% | 20.4% | 23.1% |

| Maryland | 14.8% | 14.8% | 21.9% | 18.5% | 35.9% | 35.9% |

| Massachusetts | 4.4% | 4.3% | 8.9% | 7.7% | 22.1% | 22.1% |

| Michigan | -4.0% | -0.7% | 13.7% | 16.2% | 23.6% | 27.8% |

| Minnesota | 0.0% | -1.9% | 3.2% | -20.9% | 6.3% | 6.3% |

| Mississippi | 26.6% | 26.2% | 36.0% | 15.3% | 37.4% | 38.1% |

| Missouri | 16.4% | 15.7% | 26.0% | 11.0% | 30.7% | 33.2% |

| Montana | 5.7% | 5.6% | 6.6% | -6.8% | 17.5% | 17.5% |

| Nebraska | 3.1% | 9.7% | 6.2% | 14.4% | 16.3% | 26.5% |

| Nevada | 1.0% | 2.4% | 13.8% | 20.9% | 3.9% | 10.3% |

| New Hampshire | -0.9% | -0.4% | 0.5% | -18.1% | 13.7% | 17.9% |

| New Jersey | 8.1% | 9.1% | 32.6% | 32.0% | 25.2% | 26.4% |

| New Mexico | 23.5% | 25.0% | 34.2% | 35.4% | 45.6% | 47.4% |

| New York | 5.2% | 5.2% | 9.5% | 9.5% | 5.5% | 5.5% |

| North Carolina | 6.8% | 8.0% | 18.4% | 18.7% | 26.5% | 29.4% |

| North Dakota | 0.0% | -0.1% | 3.1% | 2.0% | 9.2% | 9.2% |

| Ohio | 1.4% | 0.8% | 3.3% | -8.1% | 6.8% | 7.2% |

| Oklahoma | 6.4% | 6.4% | 11.0% | 11.0% | 10.6% | 10.6% |

| Oregon | 5.6% | 4.9% | 15.6% | 14.5% | 39.1% | 39.1% |

| Pennsylvania | 7.7% | 12.0% | 7.8% | 7.4% | 15.8% | 26.9% |

| Rhode Island | 3.4% | 3.1% | 14.1% | 0.1% | 14.9% | 14.9% |

| South Carolina | 18.2% | 16.3% | 28.3% | 12.8% | 44.2% | 44.2% |

| South Dakota | 8.6% | 8.6% | 10.0% | 7.1% | 24.4% | 24.4% |

| Tennessee | 22.1% | 22.1% | 20.4% | 19.3% | 47.2% | 47.2% |

| Texas | -0.7% | -2.7% | 5.5% | 5.3% | 16.5% | 20.7% |

| Utah | 13.4% | 13.4% | 24.3% | 25.1% | 47.1% | 48.8% |

| Vermont | 12.5% | -14.3% | 0.4% | -24.1% | 34.8% | 57.5% |

| Virginia | 13.3% | 8.7% | 21.2% | 20.2% | 48.9% | 48.9% |

| Washington | 9.8% | 9.8% | 7.1% | 4.5% | 39.0% | 39.0% |

| West Virginia | 1.5% | -1.3% | 2.1% | 5.1% | 14.4% | 17.8% |

| Wisconsin | 2.0% | -0.2% | 6.9% | 2.4% | 16.5% | 16.5% |

| Wyoming | 2.4% | 5.1% | -8.2% | -27.9% | -5.8% | -2.6% |

| U.S. | 6.6% | 5.3% | 16.4% | 13.2% | 27.5% | 28.9% |

| D.C. | -5.2% | -6.2% | 8.0% | -19.7% | 39.6% | 42.5% |

After four years at Princeton University, Avina Ross left her job in September 2021. She was one of three DEI employees who have resigned from the institution over the past 18 months due to what they described as a lack of institutional support for their work, according to a December article in the student newspaper, The Daily Princetonian.

Ross, who is Black and has a doctorate in social work, was hired by Princeton’s health services department in part to provide a culturally sensitive approach to violence prevention and support for sexual abuse survivors. But she told Inside Higher Ed there was a disconnect between her goals for making the university more inclusive and the expectations of Princeton’s leaders, who she said had at best a “surface-level investment” in DEI work.

“That kind of environment can really lead to an exodus, and that’s what you had at Princeton,” Ross said.

In an email to Inside Higher Ed, Princeton spokesperson Michael Hotchkiss disputed Ross’s assessment of the university’s commitment to DEI work.

“There is a shared and continual commitment to ensuring a diverse and inclusive environment at the university in which all staff members can thrive,” he wrote.

In addition, Michele Minter, Princeton’s vice provost for institutional equity and diversity, noted that the university’s approach to DEI is not “top-down,” so each department develops its own initiatives.

The departures at Princeton are part of a pattern in higher education, according to nearly a dozen college and university DEI administrators and staffers who spoke with Inside Higher Ed. While some institutions have elevated their highest-level DEI officers to senior positions or even president, the employees interviewed for this article said that more often, university leaders show a lack of appreciation and support for their work, leading them and many of their colleagues to leave higher ed burned out and disillusioned.

Compounding those challenges is an increasingly aggressive political attack on DEI initiatives by conservatives across the country. Texas lawmakers have proposed legislation to ban DEI work in public higher ed outright. Last week, Oklahoma’s new Republican superintendent of public instruction issued a letter requiring the state’s public colleges to account for “every dollar spent” on DEI in a potential effort to curb that spending. And on Tuesday, Florida governor Ron DeSantis announced plans to defund all DEI offices across the state’s higher education system, the latest in a long string of political maneuvers that includes the recent appointment of two vocal anti-DEI activists to the New College of Florida’s Board of Trustees.

Despite the increase in political hostility, the number of senior DEI roles is steadily multiplying. Between 2020 and 2022, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, membership in the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education increased by 60 percent, according to Paulette Granberry Russell, the association’s president. At the same time, she added, senior diversity officers increasingly come from diverse backgrounds and are thus likely to experience the difficulties of being a rare leader of color in the predominantly white world of higher ed administration.

“The vast majority of our members come out of communities that have been historically underrepresented or marginalized in higher ed,” Granberry Russell said. “There’s an emotional toll, and that’s exacerbated when you have inadequate resources and support or when the job is tokenizing.”

For Ross, that emotional burden eventually became too heavy to bear.

“That’s the double-edged sword of DEI work: in this space, the learning doesn’t end. And the more you learn, the more you start taking a look at your own experiences and applying that lens to them,” Ross said. “Eventually you might ask yourself, ‘Is this a sacrifice that I’m willing to make?’”

When those issues lead to frequent departures, it can have long-term consequences for the entire institution.

“That kind of burnout and turnover really does have a negative effect on DEI work,” said Nicholas Creary, a former co–chief diversity officer at Moravian College. “It means that every couple of years or even less, you have to reset the needle and start over.”

Last March Creary was removed from his role as co-CDO at Moravian for, as he put it to Inside Higher Ed shortly after his departure, “doing his job well.” After being recruited for the CDO position and offered a simplified tenure process as a history professor, Creary began getting pushback for making negative comments about the college’s diversity practices. When he later shared minority faculty retention data with colleagues, Moravian accused him of committing “an egregious violation of university policy,” according to an email the college sent to Creary’s lawyer.

Inside Higher Ed previously reported on the circumstances surrounding his departure, which Creary declined to elaborate on in a recent interview due to a nondisparagement agreement he signed with the college. Last April a spokesperson for Moravian told Inside Higher Ed via email that Creary was fired “for cause” and declined to comment further.

Institutional culture can have a major impact on a DEI officer’s experience, Creary said. Some campuses are invested in the work and take it seriously; others are merely looking for someone to mediate conflict with students and faculty of color—to “patch ’em up and push ’em through,” as Creary put it. Managing the expectations and attitudes of leaders and colleagues can be a significant part of the job.

“There are a lot of places that are [hiring CDOs] because they have to check the boxes, to say we’ve got somebody doing diversity,” Creary said. “At some institutions, it’s not even a question of will they support the work; it’s a matter of getting them not to obstruct it.”

Often, DEI officers part ways with their institution under less-than-amiable circumstances. Of the 10 sources who spoke with Inside Higher Ed for this story, three had reached or pursued settlements with their former employers over discrimination or contract disputes.

Cecil Howard said he resigned as vice president for diversity, inclusion and equal opportunity at the University of South Florida in July 2021, after years of “frustration and disrespect” boiled over into open conflict with the university’s then president, Steve Currall.

Some of that conflict was incited by what Howard called “an incredibly tone-deaf and disrespectful” statement that Currall made after Floyd’s murder. But more than that, Howard said he left because he felt undermined and belittled at every turn, a pattern that slowly reinforced his belief that his role at USF was no more than “window dressing.”

“Everybody wants to hire a chief diversity officer to throw a Black History Month event or read a land acknowledgment,” he said. “But when the rubber meets the road—when we’re at least aspiring to become an antiracist environment—those senior leaders and major decision-makers, they don’t want to hear it. I was never going to be OK being a pawn, a token, a box-checker. So I left.”

Althea Johnson, USF’s director of media relations, told Inside Higher Ed via email that prior to his resignation Howard submitted two charges of discrimination with the Florida Commission of Human Rights, which has since dismissed both.

Howard said being a DEI administrator is especially difficult in red states like Florida or Texas, considering the vitriol state lawmakers have expressed for work they see as a symptom of administrative bloat or a tool for politically motivated indoctrination.

“I tell people, I live in Florida but I won’t do my work here,” Howard said. “People who are very talented won’t come to Florida to do this work anymore, or a number of other states. I said no to a job in Tennessee recently for the same reasons.”

Michael Dixon, a diversity officer with nearly two decades of experience in higher ed, said those concerns are increasingly important for many in his line of work; a friend of his recently turned down an offer in Florida after considering the political challenges.

“There’s no way we can work effectively if we have to consistently justify the work we’re doing,” he said. “This job is challenging enough as it is.”

More common than outright conflict between DEI staff and institutional leaders, though, is a general sense of discouragement and frustration. This can result in DEI staffers hopping from job to job, hoping to find a good fit.

“I think that’s often a result of institutions that have not clearly defined the expectations of the position, what they regard as priorities,” said Granberry Russell. “The important thing is making sure that people come into the roles adequately prepared and that those who are developing those roles understand what it takes to not only realistically set goals, but also support that individual in pursuing them.”

Dixon resigned from his last job, as chief diversity officer at Susquehanna University, in December. He said he’s proud of his work at the Pennsylvania institution, but that he felt a disconnect between “the way that position was initially crafted and what it turned out to be.” And at his first CDO job, at Manchester University in Indiana, he said he had so little access to the president and other senior leaders that he felt unmoored and ignored, “without the ability to make meaningful change.” He left after two years.

“If you have the support of the institution and leadership reinforcing your message, your work becomes a lot easier,” he said. “Otherwise it just kind of feels like you’re shouting down an empty hallway.”

Kevin McDonald, the University of Virginia’s vice president for diversity, equity, inclusion and community partnerships, said he “has a real partner” in UVA president James Ryan and other senior leaders. Though he knows that’s “rare” in his field, he said it’s the “most important factor” in making DEI work fulfilling and impactful.

“If those relationships are watered and seasoned, they will grow and bloom and benefit not only the president and the CDO, but the whole institution,” McDonald said.

Sabrina Gentlewarrior has spent 19 years working at Bridgewater State University in Massachusetts, the last dozen as vice president for student success and diversity. She said the university has been supportive of her and her colleagues’ “long-term work” to make the institution more welcoming for faculty and students of color, and that the commitment has made a real difference to the DEI staff.

“There was a real rush to emphasize this work on campuses; that was needed and good. But many campuses have not yet lived up to their promises,” she said. “It can be exhausting for workers in this field when their institutions haven’t matured from minor diversity programming to making strides toward institutional change.”

Dixon said his frustration at Susquehanna and Manchester led him to question his future in DEI work—and academe.

“I’ve been really thinking about, after 18 years, is the next step another position like this? Or do I look for DEI work in the nonprofit or corporate world, or focus on my consulting firm?” he said.

Howard, formerly of USF, has already made up his mind.

“It got to the point where I don’t want to do this work anymore, as much as I care about it,” he said. “An experience like the one I had will just take the wind out of your sails.”

McDonald, who has mentored other CDOs, said that building community is especially important for those working in DEI.

“We’ve lost some amazing individuals in the field because of this, people who are kind of used and abused by their institutions,” he said. “Being a diversity officer can be such a lonely job … it’s important that we be there for each other.”

Creary said the thorny circumstances surrounding his departure from Moravian have created “some challenges finding a next permanent gig” in higher ed. Nonetheless, he is determined to stick with it.

“It’s frustrating and can be disheartening,” Creary said. “But ultimately, if you believe in the work—and more importantly, if you believe in and want to help those students and those faculty that are hurting—you do it anyway.”

Months after revelations of financial turmoil spurred a state investigation at New Jersey City University, legislators want to make sure they’re not caught by surprise the next time a public institution faces a crisis.

To that end, they’ve introduced three pieces of legislation designed to beef up financial oversight of the state’s colleges and universities.

One bill would require institutions to file an annual fiscal monitoring report with the Office of the Secretary of Higher Education—New Jersey’s highest authority on higher ed, who answers to the governor—and submit to an audit by that office every three years. It would also give the secretary the power to appoint a monitor to oversee an institution’s fiscal operations if an audit is particularly troubling.

Another bill would require institutions to post the results of those reports to their website “in a manner understandable to the general public.” And the last bill would mandate training programs in financial higher ed management for members of institutions’ governing boards.

New Jersey invested nearly $2.8 billion in its public higher education institutions last fiscal year, and the governor has proposed a $100 million increase for FY2023. Brian Bridges, New Jersey’s secretary of higher education, said the legislation would help ensure that investment is managed responsibly.

“As these students and their families make these difficult decisions about where to go to college, we just want to make sure that we’re being good, transparent stewards of those investments—the personal investments of the families as well as the state investments,” Bridges told Inside Higher Ed.

Dustin Weeden, a senior policy analyst at the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, said the bills would put New Jersey on par with most other states’ fiscal oversight measures. But many of those states don’t need legislation to mandate government oversight because they have a centralized governing body to keep them accountable. New Jersey, on the other hand, has a decentralized higher education system, with no statewide governing board for its public colleges and universities—making it one of only 14 such states in the country, according to a 2016 study by the Education Commission of the States.

“If there was a centralized governing board within the state, like North Carolina or the Georgia system, they would likely be directly involved in the budgeting and financial situation of institutions already,” Weeden said.

Michael Klein, former executive director of the New Jersey Association of State Colleges and Universities, a nonprofit that advocates for the state’s public institutions, said the most significant part of the package of legislation is its training requirement for board members—something many states have considered over the past decade. He said even though members of college and university boards might be well versed in nonprofit or corporate finance, higher education is “a whole different world.”

“If you’re going to give boards more power and responsibility, like they have in New Jersey, you have to make sure they’re prepared,” he said.

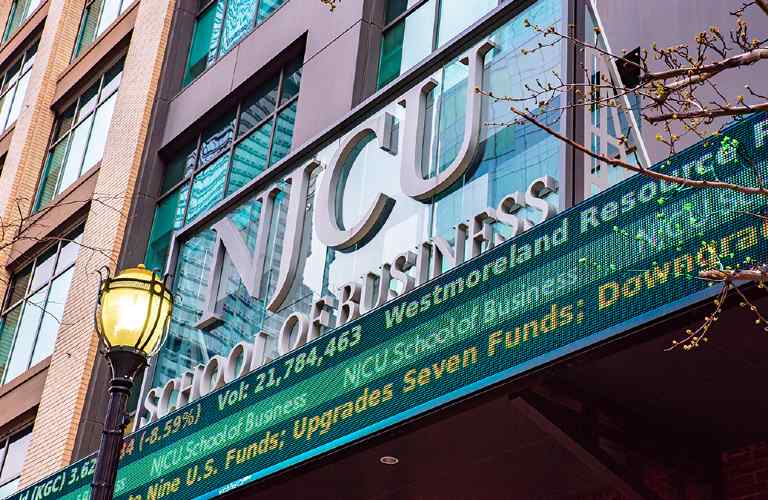

The bills are at least in part a response to last year’s budget crisis at New Jersey City University, where plummeting finances prompted a state investigation that is still ongoing. The institution reported a $67 million deficit in 2022, down from a $180 million surplus less than a decade prior and a $100 million surplus in 2021. NJCU’s former president, Sue Henderson, stepped down last July amid allegations of financial mismanagement. Last month the university announced that it would lay off 30 faculty members and cut 37 percent of its 171 academic programs as part of a budget-balancing strategy.

A spokesperson for NJCU said the numbers don't tell the whole story, and that reporting on the issue has conflated the university's "net position" with a budget surplus. He said the figures were the result of standards put in place in 2015 requiring state institutions like NJCU to report pension obligations, which, he added, had a negative impact of $115 million on the university's reported net position. (This paragraph has been added to clarify NJCU's position.)

NJCU isn’t the only public university in New Jersey facing a severe financial shortfall, due mainly to declining enrollment. William Paterson University reported a nearly $30 million deficit in 2021 and ended the year by announcing plans to lay off 100 full-time faculty members—nearly a third of its professors—and shutter two of its majors, as well as put a number of others on hiatus.

“I think it’s fair to say that some public trust has been eroded, and that’s where the Legislature and governor are stepping in,” Klein said. “They wouldn’t be filing legislation if this weren’t on everyone’s minds.”